Abstract

We aimed to model binding of donor antibodies to virus that infects COVID-19 patients following transfusion of convalescent plasma (CCP). An immunosorbent assay was developed to determine apparent affinity (Kd, app). Antibody binding to virus was modelled using antibody concentration and estimations of viral load. Assay and model were validated using reference antibodies and clinical data of monoclonal antibody therapy. A single Kd, app or two resolvable Kd, app were found for IgG in 11% or 89% of CCP donations, respectively. For IgA this was 50%-50%. Median IgG Kd, app was 0.8nM and 3.6nM for IgA, ranging from 0.1-14.7nM and 0.2-156.0nM respectively. The median concentration of IgG was 44.0nM (range 8.4-269.0nM) and significantly higher than IgA at 2.0nM (range 0.4-11.4nM). The model suggested that a double CCP transfusion (i.e. 500 mL) allows for > 80% binding of antibody to virus provided Kd, app was < 1nM and concentration > 150nM. In our cohort from the pre-vaccination era, 4% of donations fulfilled these criteria. Low and mid-range viral loads are found early post exposure, suggesting that convalescent plasma will be most effective then. This study provides a biochemical rationale for selecting high affinity and high antibody concentration CCP transfused early in the disease course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transfusion of COVID-19 convalescent plasma (CCP) was adopted widely during the past pandemic1. It served as an emergency treatment in the absence of natural immunity or effective antivirals and vaccines. A recent meta-analysis found that CCP transfusion does not reduce mortality nor improves or worsens clinical impact in individuals with moderate to severe COVID-19 compared to placebo or standard of care2. Meta-analyses that aggregate selected clinical trials indicate that transfusion of CCP with high antibody titres3 or transfusion of CCP in outpatients4 may be efficacious in these specific conditions.

Treatment success is also dependent on CCP potency5,6,7,8,9. This is defined here as the propensity of a given CCP to inhibit infection by SARS-CoV-2. The actual real-life potency of CCP depends on many factors, general and local. These include the antibody titre at the site of infection following transfusion, the prevailing viral strain, the antibody congruence with viral epitopes, antibody affinity, viral antigen concentration as well as biochemical and biophysical conditions that make up the environment where antibody-antigen binding occurs. It is thus impossible to measure actual CCP potency with the current state of the art. Therefore scientists approximate CCP potency using laboratory assays that measure antibody titres10. These have advantages and disadvantages but taken together most quantitative assays correlate well with each other11. In addition, antibody titres or concentrations also correlate well with (pseudo)virus neutralization assays in vitro12,13,14.

Currently, none of these assays takes into account antibody affinity defined as the half maximal binding of antibody to antigen. The corresponding physical quantity is the equilibrium constant K and is an inherent biochemical property of any given antibody. It allows to scope the concentration range in which successful binding between virus and antibody takes place. In CCP, many different antibodies are dissolved in a protein matrix representing a range of several individual affinities. Any affinity assay will thus report the dominant species masking the true underlying affinity distribution in a given CCP. This is however often the case in affinity measurements in biochemistry and should not be a critical limitation15, given that this dominant affinity will represent the dominant functional component. It is unclear if antibody affinity is a valuable discriminator for CCP selection. In addition, equilibrium constants have not been used to model virus binding to transfused CCP antibody.

Therefore, we developed a competition immunosorbent assay that reproducibly determines apparent affinity constants (Kd, app) in CCP. The data allow to estimate the fraction of virus bound by CCP antibodies using a mathematical model of equilibrium binding and predicts therapeutic or prophylactic success as a function of viral load in the respiratory tract of a patient.

Results

Validation of the apparent affinity ELISA

The set-up and data-analysis of the apparent affinity ELISA were validated by testing recombinant monoclonal anti-RBD human antibodies of isotype IgG with known Kd. The monoclonals were supplemented in non-immune plasma (NIP) to have the same matrix as CCP. The high affinity monoclonal CR3022 has a Kd of 15 to 30 nM and the low affinity monoclonal AS35 has a Kd of 88 nM, both determined by surface plasmon resonance16,17. When supplemented with either one of these, data fitted to a unimodal binding equation (Fig. 1a), confirming the presence of a single affinity. The resulting Kd, app was 23.0 nM [95%CI 19.7;27.6] for CR3022 and 99.8 nM [95%CI 80.9;130.7] for AS35 which matched the reported Kd. When supplemented with both, data fitted to a bimodal binding equation with Kd, app1 2.5 nM [95%CI 1.4;10.0] and Kd, app2 254.4 nM [95%CI 185.7;403.9] (Fig. 1b). Figure 1c and d depict two representative CCP containing either one dominant Kd, app or two discernible Kd, app1 and Kd, app2, respectively.

Validation of the apparent affinity assay. (a) NIP was supplemented with either monoclonal anti-RBD antibody CR3022 (black, reported Kd 15 to 30 nM) or AS35 (blue, reported Kd 88 nM). Each dot represents the mean corrected absorbance at 450 nm (A450nm) of three technical repeats. Data were fitted by non-linear regression, the unimodal relation (dashed line) was selected. (b) NIP was supplemented with both monoclonal anti-RBD antibodies and analysis was repeated, bimodal (full line) was selected over unimodal (dashed line). (c) A representative CCP selected for unimodal binding or (d) bimodal binding. Both fits (full and dashed line) are depicted for comparison. (a-d) When regressions met predefined quality criteria, statistical analysis was performed to select best fit by a sum-of-squares F-test (bimodal binding in case P < 0.001).

Apparent affinities of IgG and IgA in CCP

To find differences between antibody isotypes, we determined Kd, app of IgG and IgA in 74 transfused CCP samples. In 89% (66/74) of samples the IgG data fit best with bimodal binding, while the remaining 11% (8/74) with unimodal binding. In 42% (31/74) of samples the IgA data fit best with bimodal binding, while the remaining 49% (36/74) with unimodal binding. In 9% (7/74) of samples Kd, app could not be reliably measured. The median unimodal Kd, app of 0.8 nM for IgG was significantly smaller than the 3.6 nM for IgA (P = 0.0003) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S1). The median bimodal Kd, app1 of 0.5 nM for IgG was significantly smaller than the 1.1 nM for IgA (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2b) while Kd, app2 was not different between IgG and IgA (P = 0.1057) (Fig. 2c).

Kd, appof IgG and IgA in CCP samples. (a) Bar graph summarizing Kd, app for IgA (blue) (n = 36) and IgG (green) (n = 8) in CCP’s that were selected for unimodal binding. (b, c) Bar graphs summarizing Kd, app1 and Kd, app2 for IgA (blue) (n = 31) and IgG (green) (n = 66) that were selected for bimodal binding. Bar and whiskers represent median and interquartile range, respectively. The median value (nM) is depicted next to the dotted vertical line that intersects the x-axis. Statistical significance between cohorts was calculated by Mann-Whitney test. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns = not significant.

Antibody concentration and virus neutralization in CCP

To allow biochemical modelling of antibody binding to virus, antibody affinity (Kd, app) and concentration are required as well as antigen (i.e. virus) concentration. Therefore, the actual molar concentration of IgG and IgA in all 74 CCP samples was determined next. We found a median anti-RBD concentration of 44.0 nM for IgG that was significantly higher than the 2.0 nM for IgA (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3a, b). For IgG, 2 samples were below the 7.0 nM LOD and for IgA 7 samples were below the 0.4 nM LOD. These samples were excluded from statistical analysis (Supplementary Table S2).

Immunoglobulin concentration and virus neutralization in CCP samples. (a, b) Bar graphs depicting IgG and IgA concentration. Bar and whiskers represent median and interquartile range. The median value (nM) is depicted next to the vertical dotted line intersecting the x-axis. Statistical significance was calculated by Mann-Whitney test; ****P < 0.0001. (c) Neutralization titres obtained by microneutralization assay (grey) and inhibition ELISA (purple) are depicted in IU/mL in a violin plot. Median (bold font, dashed line) and interquartile values (regular font, dotted line) are depicted in the violin plot. (a-c) Red dots indicate values below the LOD or LOQ. (d) Spearman rank correlation analysis between neutralization and inhibition assay from panel c (n = 55). (e, f) Spearman rank correlation analysis between (e) IgG or (f) IgA concentration and the inhibitory antibody titre (n = 73). Statistical outcome data are given as inserts in the right, bottom corner of each panel.

The median neutralization titre by microneutralization assay was 74.0 IU/mL [95% CI 74.0; 588.0] (n = 55) (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table S2). One sample was not measured in the assay. Eighteen samples (25%, 18/73) had a titre below the 36.8 IU/mL LOQ and were not included in the statistical analysis. In 21/55 samples (38%) the titre was ≥ 294.0 IU/mL. Using a commercially available inhibition ELISA, a median inhibitory antibody titre of 192 IU/mL [95% CI 125; 390] was found (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table S2). One sample was below the LOQ. Spearman rank correlation analysis between the microneutralization assay and the inhibition ELISA data shown in Fig. 3c was not significant (r = 0.16, P = 0.2552; n = 55) (Fig. 3d). Correlation between IgG concentration and inhibition ELISA was significant (r = 0.91, P < 0.0001; n = 73) (Fig. 3e). There was no correlation between IgA concentration and inhibition ELISA (r = 0.41, P = 0.0003; n = 73) (Fig. 3f).

Antibody binding to virus, modelled by concentration and Kd, app

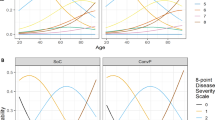

The fraction of antibody bound to virus was calculated. Hereto, antibody concentration and apparent affinity were entered into the algorithm to determine the fraction of antibody bound to physiologically relevant ranges of RBD concentrations as a proxy for virus concentration. These RBD concentrations were calculated based on actual viral RNA measurements in patients and animals18,19,20 (Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Table S3). A CCP containing > 180 nM of IgG and Kd, app1 of 0.3 nM had sufficient, high affinity IgG antibodies to saturably bind the virus in all relevant ranges (Fig. 4c). Transfusion then shifted the binding curve to the left and the plateau down, but still allowing > 80% binding in relevant virus ranges. A CCP containing > 260 nM of IgG but Kd, app1 >10 nM does not have sufficient, high affinity IgG antibodies to bind virus at any concentration (Fig. 4d). Transfusion impacted the binding curve reducing binding to below 25%. A CCP containing < 10 nM of IgG and Kd, app1 of 0.1 nM had sufficient, high affinity antibody to bind nearly all virus in all relevant ranges. Transfusion significantly impacted binding only reaching 70% saturation at low viral loads in case of double transfusion (Fig. 4e). From these data follows that the second discernible IgG subpopulation with Kd, app2 > Kd, app1 is only marginally contributing to the fraction of virus bound by antibody (< 25%) (Supplementary Figure S1). The same holds for IgA which can have high affinity (Fig. 2b), but was generally low in concentration (Fig. 3b) leading to significantly decreased virus binding after transfusion, with maximal binding of 20% even at low viral doses for the example in Fig. 4f.

Fractional antibody binding of virus. (a, b) RBD concentrations were derived from reported SARS-CoV-2 RNA data in regular aerosol transmissions and by coughing of a COVID-19 patient (a) or extrapolated from SARS-CoV-2 RNA data found in the respiratory tract of rhesus macaques during peak of infection (b). (c-f) The fraction of RBD bound by IgG (green line) or IgA (blue line) in CCP was calculated for four representative samples in the cohort; (c) high IgG concentration with a high affinity, (d) high IgG concentration with a low affinity, (e) low IgG concentration with a high affinity and (f) low IgA concentration with a high affinity. Binding was modelled during theoretical infection of the CCP donor (open dots, ○), after a single (i.e. 250 mL; open triangles, Δ) or double CCP transfusion in a COVID-19 patient (i.e. 500 mL; open squares, □).

Optimal CCP

To demonstrate clinical relevance, we validated our model of virus binding using real life clinical data from the REGN-COV passive immune therapy that had proven efficacy in a clinical trial21. We used the actual Kd (~ 0.05 nM) and pharmacokinetic data of the high or low dose REGN-COV therapy intervention in the study corresponding to 4000 mg or 1200 mg per patient21. The mean Ig concentration after a single intravenous dose of the high or low dose REGN-COV therapy in a patient was 1048 mg/L (6993.3 nM) and 321 mg/L (2140.0 nM), respectively. When plugged into our model, the REGN-COV data indicate sufficiently high affinity antibody binding to all viral loads following infusion in clinical trial participants (Fig. 5a). Both reported REGN-COV doses bound saturably to even the highest viral loads found in the respiratory tract during peak infection.

Selecting optimal CCP. (a) Simulation of the fraction of antibody bound to virus in clinical trial participants after administration of high (4000 mg, red line) or low dose (1200 mg, green line) REGN-COV (∇). (b) Fraction of antibody bound to virus using CCP from a convalescent, vaccinated CCP donor and (c) a donor with known very high antibody concentration and low Kd23. Data representation is as in Fig. 4. (d) The distribution of CCP samples (n = 74) by IgG concentration and Kd, app or Kd, app1. Colour coded according to arbitrary Kd, app ranges: below 1 nM (high affinity, blue), between 1 and 10 nM (mid affinity, orange) and above 10 nM (low affinity, purple). The green box indicates the CCP samples with a high affinity and high IgG concentration. The dotted lines intersecting the x- and y-axis represent respectively the cut-off at 150 nM IgG and 1 nM Kd, app.

Next, we modelled a very high titre CCP from one of our donors who recently recovered from a SARS-CoV-2 infection and donated 21 days post booster vaccination. Such donors consistently have the highest reported doses of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and are considered optimal CCP donors22. This CCP contained sufficient, high affinity IgG to bind almost all virus at relevant ranges (Fig. 5b). Transfusion however shifted the binding curve to the left and the plateau down resulting in a maximal binding of < 80%. We screened literature to find potential CCP donors with even higher antibody concentrations at low Kd. In Emmeneger et al.23 one study participant had a plasma concentration of 1000.0 nM IgG at a Kd of 3.0 nM. If this was donated as CCP, then transfusion still shifted the curve significantly to not cover saturable binding over all viral ranges (Fig. 5c).

In our donor cohort, the IgG concentration was consistently below 300 nM while 74% (55/74) of samples had subnanomolar Kd, app1 (Fig. 5d). This implies that the fraction of antibody bound to virus was > 80% following a double transfusion (i.e. 500 mL) in 4% (3/74) of cases when an IgG concentration > 150 nM and Kd, app <1 nM is taken as thresholds. Note that none of these would be able to saturably bind virus in all relevant ranges.

Discussion

Our study aimed to model the fraction of antibody bound to virus in COVID-19 patients. The model is based on principle of equilibrium binding taking into account affinity and the concentrations of both antigen and antibody in patients getting a CCP transfusion. The concentration of antibody is obtained in the laboratory by quantitative ELISA, but the viral protein in a patient cannot be exactly determined. The viral load evolves over time during infection and may differ depending on the anatomical location. Therefore, we plotted antibody-antigen binding over a range of possible viral loads. This approach was validated using real clinical data of the REGN-COV therapy. REGN-COV is a form of passive immune transfer similar to CCP transfusion, the former as a medicinal product and the latter as a blood product. REGN-COV has a high affinity for SARS-COV-2 antigen and was dosed to high concentrations in clinical trial participants. REGN-COV efficacy was demonstrated clinically in patients of whom viral loads were actively monitored. Our model indeed confirms saturable REGN-COV antibody binding to antigen over the relevant ranges of viral doses. CCP sampled from our ‘early (pre-vaccinated) cohort’ never reached the doses administered in the REGN-COV trial and the highest affinities are 2- to 10-fold lower compared to the REGN-COV antibodies. The low antibody dose in the CCP donations in combination with limited crossing of systemically administered antibodies to the mucosa may explain why CCP transfusion was not efficacious for individuals with moderate to severe disease versus placebo or standard care alone24,25,26. Following vaccination, high titre CCP became available increasing the likelihood of virus binding compared to convalescent plasma obtained in the early days of the pandemic. Although seemingly rare, CCP may contain high concentration of antibody with low affinity suggesting that affinity measurements may be used to unselect these for transfusion given that transfusion and limited blood-mucosa crossing will dilute the bolus dose.

Although it is tempting to consequently prefer factory-designed cocktails like REGN-COV, these present some major disadvantages over CCP during an ongoing pandemic. One disadvantage is its high cost of development and of routine production, restricting such cocktails to high income countries. Another is that medicinal products do not self-adapt, while CCP co-evolves with the prevailing virus strains. Consequently, CCP is still of use but probably requires very high titres with high affinities to effectively treat COVID-19 patients5,6,7,8,9,24.

Following transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to a naive individual, the viral load starts building up from zero. The model suggests that only the CCP donations with high antibody concentrations above 150 nM and a subnanomolar affinity allow antibody-antigen binding, reaching a plateau of 80% virus binding following a double transfusion. Therefore, it makes sense that early or very early transfusion of high affinity CCP will be most effective for treatment of COVID-19. This is indeed the current hypothesis for CCP transfusion success27. Given this information, preventive interventions with CCP are likely to be more effective than curative ones. Data from our group suggests this can work, because intranasal administration of high titre, high affinity CCP effectively prevents transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a hamster model28. Even low titre, high affinity CCP that was collected prior to vaccination was efficacious in this animal model, albeit less efficacious than high titre. This is in line with data showing that only 4–16% of intravenously administered immunoglobulins effectively reach the mucosa29,30,31,32. Post-exposure prophylaxis by transfusion is also possible33 and is equally likely to be more effective than treatment of ongoing COVID-19. Because transfusion is an intravenous intervention, practical and regulatory reasons restrict post-exposure prophylaxis to patients at risk of developing lethal pneumonia. For the same reasons, CCP transfusion as a general intervention for pre-exposure prophylaxis has not been considered34.

The theoretical assumptions that we made to obtain Kd, app and model antibody-antigen binding need some elaboration to highlight study limitations. We have assumed RBD as sole antigen to approximate virus binding. The humoral response however is not restricted to RBD as a foreign antigen and the immunoglobulins have more functions than strict sterical inhibition of binding35. The focus on RBD therefore is an oversimplification. In addition, we have assumed an antibody-naive patient. Yet, many patients in the primary clinical trials that assessed CCP transfusion already had developed anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies on their own36. Transfusion to these patients thus only marginally supplements the existing contingent of innate antibodies in the patient’s plasma resulting in no clinical benefit again highlighting the importance of early CCP transfusion. A crucial requirement then still remains that affinity is high. This may explain reports of spectacular cases of successful treatment with CCP37,38 and the trends for general efficacy in certain trials9,39,40. We also assumed that RBD antigen correlates directly with viral load. To avoid bias, the ‘viral load’ x-axis in our model has been set very wide to allow interpretation over a wide, but theoretical range of viral protein. Additionally, viral load may not predict number of infectious viral particles as free viral genomes or their fragments can also be detected. Based on literature we assumed that 10% of systemically administered antibody crosses to the mucosa. Finally, label-free biosensing technologies like surface plasmon resonance41 or bio-layer interferometry42 may be used as an alternative to ELISA to obtain antibody-antigen binding strengths. Microfluidic antibody affinity profiling (MAAP) represents an elegant alternative microfluidic method that can be used to determine Kd, app in plasma provided autofluorescence of the plasma is low43.

In conclusion, our study models antibody-virus binding and can be used for both natural and passively transferred humoral immunity. The data provide a rationale for why CCP is likely to be most effective at high antibody concentrations of high affinity and upon early or prophylactic administration before the peak viral loads are reached.

Methods

Samples

CCP was collected from 74 donors from September 2020 till April 2021 when alpha and gamma were dominant strains in the donor population. Past COVID-19 infection was confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), chest computed tomography or serology. CCP was donated by an adult at least 14 days since full recovery. Neutralizing titres were determined monthly from the first donation by plaque reduction neutralization (PRNT). We included 74 CCP samples and a vaccinated CCP (2 doses Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 and booster dose Moderna mRNA-1273) in this study, provided by the Belgian Red Cross Flanders, with titres of 1:160 or higher. NIP was used as a negative control. Human material for scientific research was used complying to Belgian biobank legislation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All material was registered in the Belgian Red Cross Flanders biobank (Federal Agency of Medicines and Health Products accession number BB190034). Biobank operations are approved by the University Hospital KU Leuven Institutional Review Board (file number S62549). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Concentration ELISA

The RBD of the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 was used as antigen. Anti-RBD IgG and IgA molar concentration was determined as described28. Dilution series of known concentrations of anti-RBD human IgG1 (Catn° srbd-mab1, Invivogen, Toulouse, France) or anti-RBD human IgA1 (Catn° srbd-mab6, Invivogen, Toulouse, France) were used as reference standards. Bound immunoglobulin was detected with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibodies. Technical triplicates were performed. The LOD was 7.0 nM for IgG and 0.4 nM IgA concentration. Intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was below 15% and 20% respectively (n = 4).

Inhibition ELISA

Inhibition of RBD binding to immobilized angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) ectodomain was measured in a competition ELISA (Cat # RAS-N044-96tests, ACROBiosystems, Newark, Delaware, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The inhibitory antibody titre was expressed as IU/mL relative to the inhibition capacity of the antibodies in the WHO standard NIBSC 20/13644. The LOQ of 10 IU/mL was reported by the manufacturer.

Microneutralization assay

The microneutralization assay was performed as previously described using the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain (isolate England/02/2020)45. In brief, each sample was assayed in a two-fold dilution series, in duplicate. Each dilution was incubated with 100 median tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50) of SARS-CoV-2 and then added to VERO E6 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas US, No. CRL-1586), seeded the previous day at 40,000 cells per well on a 96-well plate. The plates were incubated for 3 days at 37 °C and surviving cells were stained with Amido Black. The plasma dilution causing 50% virus neutralization, as measured by cellular cytopathic effect, was defined as the neutralization titre consequently expressed as IU/mL relative to the neutralization potency of the WHO standard NIBSC 21/33846. Analytical sensitivity was 1.84 IU/ml and LOQ, due to 1:20 starting dilution, was 36.8 IU/mL.

Apparent affinity ELISA

Kd, app of IgG and IgA were measured by competition ELISA as described15,47,48. In brief, CCP was diluted 1/250 for IgG, 1/10 for IgA and incubated with an excess of recombinant RBD in a ½ concentration series starting from 800nM to 600nM, respectively. Next, unbound anti-RBD antibody was quantified in ELISA. Hereto, the samples were incubated with immobilized RBD at 7 nM in a microwell plate (Cat # 40592-V08H, Sino Biological, Bejing, China) and detected with HRP-conjugated secondary. Data were fitted according to an unimodal (Eq. 1) or bimodal (Eq. 2) binding equation, given below:

Where A450nm is the absorbance at wavelength 450 nm of the binding ELISA; Amax is the absorbance in the absence of competing antigen, for each detectable antibody with a given apparent affinity Kd, app; RBD is the concentration of unbound recombinant RBD.

For data analysis, background values obtained from the NIP sample were subtracted from the raw data. These corrected absorbances were fitted by non-linear regression to the equations (Eq. 1) and (Eq. 2). Outliers were detected and excluded during analysis using the robust regression and outlier removal (ROUT) method with a false discovery rate less than 1.0%. In case both regressions met predefined quality criteria listed below, a sum-of-squares F-test (bimodal binding in case P < 0.001) was conducted for model selection. The unimodal binding resulted in a single Kd, app while for bimodal binding a Kd, app1 and Kd, app2 was defined.

Quality criteria for regression:

-

R2 ≥ 0.7

-

Kd, app confidence interval ≥ 0.

-

(A800nM-A0.003nM) ≥ 1; where A is the absorbance at wavelength 450 nm of the samples with RBD test concentrations given in the subscript.

Our method was validated using two commercially available recombinant monoclonal human IgG’s referred to as CR3022 (Catn° srbd-mab1, Invivogen, Toulouse, France) and AS35 (Catn° SAD-S35, ACROBiosystems, Newark, Delaware, USA).

Model of CCP antibody binding to virus

We can calculate the equilibrium concentration of antibody-antigen complex [C] using the known total concentrations of antibody Abtotal in mucosa and antigen RBDtotal. The textbook Eqs. 3 and 4 for affinity Kd resolve to Eq. 5, assuming antigen and antibody interact saturably as a single ligand to single receptor binding site without cooperativity of any kind.

This in turn allows to estimate the fraction f of antibody bound (Eq. 6) to RBD over a pre-set range of RBD concentrations.

The fraction f of antibody bound to RBD was calculated during infection in a potential CCP donor and in a hypothetical patient after a single 250 mL or double 500 mL CCP transfusion. The Ig concentration was divided by 12 or 6, i.e. 250 mL or 500 mL in 3 L plasma volume. A realistic range of RBD concentrations in mucosa of the respiratory tract49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56was derived from SARS-CoV-2 RNA published data (Supplementary Table S3). These publications reported viral RNA in air and cough samples shed by SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals19,20. The viral load in the respiratory tract during peak infection was extrapolated by data from rhesus macaques18. In the text, we arbitrarily distinguish between low (102-104 viral RNA/mL), mid (105-107 viral RNA/mL) and high (108-1011 viral RNA/mL) RBD concentrations, i.e. viral doses.

Assumptions

-

We assume that following transfusion, Abtotal is the concentration of antibody with a given Kd, app in the patient’s circulation assuming the patient did not mount any humoral response her-/himself and consequently does not have anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies prior to transfusion.

-

We assume normal dilution of CCP takes place following transfusion and this is based on the total plasma volume of a hemodynamically stable patient (~ 3 L).

-

Experiments that track intravenously administered radiolabeled immunoglobulins31,32 show that on average 10% is delivered in the respiratory tract29,30.

-

We assume classical Langmuir equilibrium binding resulting in a dynamic equilibrium of three species: free antibody and free RBD in equilibrium with bound antibody-antigen complex.

-

We assume that the RBD concentration correlates to virus concentration (~ 120 RBD proteins/virion)18 in the theoretical volume of the model.

Data analysis and statistics

Data were processed in GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). The data of the apparent affinity ELISA were fitted with a custom-built application in Matlab Version 9 (MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts, USA).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Rojas, M. et al. Convalescent plasma in Covid-19: possible mechanisms of action. Autoimmun. rev.19, 102554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102554 (2020).

Iannizzi, C. et al. Convalescent plasma for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst. Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013600.pub6 (2023).

Senefeld, J. W. et al. Mortality rates among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 treated with Convalescent plasma: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proceedings: Innovations Qual. Outcomes. 7, 499–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2023.09.001 (2023).

Levine, A. C. et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Convalescent plasma outpatient therapy to prevent outpatient hospitalization: a Meta-analysis of individual Participant Data from 5 randomized trials. Clin. Infect. Dis.76, 2077–2086. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad088 (2023).

Körper, S. et al. Results of the CAPSID randomized trial for high-dose convalescent plasma in severe COVID-19 patients. J. Clin. Investig.131, e152264. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI152264 (2021).

Joyner, M. J. et al. Convalescent plasma antibody levels and the risk of death from Covid-19. N Engl. J. Med.384, 1015–1027. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2031893 (2021).

Bartelt, L. A. et al. Outcomes of Convalescent Plasma with defined high versus lower neutralizing antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 among hospitalized patients: CoronaVirus Inactivating plasma (CoVIP) study. mBio. 13, e0175122. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01751-22 (2022).

Belov, A. et al. Early administration of COVID-19 convalescent plasma with high titer antibody content by live viral neutralization assay is associated with modest clinical efficacy. Am. J. Hematol.97, 770–779. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26531 (2022).

Libster, R. et al. Early high-titer plasma therapy to prevent severe Covid-19 in older adults. N Engl. J. Med.384, 610–618. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2033700 (2021).

Letter of Authorization, Reissuance of Convalescent Plasma EUA February 4. (2021). https://www.fda.gov/media/141477/downloadUS Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, (2021).

Steenhuis, M. et al. Quality assessment and harmonization of laboratories across Europe for multiple SARS-CoV-2 serology assays. Vox Sang. 118, 666–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/vox.13480 (2023).

Harvala, H. et al. Convalescent plasma therapy for the treatment of patients with COVID-19: Assessment of methods available for antibody detection and their correlation with neutralising antibody levels. Transfus. Med.https://doi.org/10.1111/tme.12746 (2020).

Steenhuis, M. et al. Dynamics of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent plasma donors. Clin. Transl Immunol.10, e1285. https://doi.org/10.1002/cti2.1285 (2021).

Luchsinger, L. L. et al. Serological assays Estimate highly variable SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody activity in recovered COVID-19 patients. J. Clin. Microbiol.58https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.02005-20 (2020).

Hofbauer, C. J. et al. Affinity of FVIII-specific antibodies reveals major differences between neutralizing and nonneutralizing antibodies in humans. Blood. 125, 1180–1188. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-09-598268 (2015).

Huo, J. et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by Destruction of the Prefusion Spike. Cell. Host Microbe. 28, 445–454e446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2020.06.010 (2020).

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD Neutralizing Antibody Human IgG1 (AS35). https://www.acrobiosystems.com/static/main/products/pdf/ds/SAD-S35.pdf AcroBiosystems (2023).

Sender, R. et al. The total number and mass of SARS-CoV-2 virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.118https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024815118 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Viral emissions into the air and environment after SARS-CoV-2 human challenge: a phase 1, open label, first-in-human study. Lancet Microbe. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00101-5 (2023).

Baselga, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Droplet and Airborne Transmission Heterogeneity. J. Clin. Med.11https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092607 (2022).

Weinreich, D. M. et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl. J. Med.384, 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2035002 (2021).

Seidel, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination of convalescents boosts neutralization capacity against SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron that can be predicted by anti-S antibody concentrations in serological assays. Preprint at MedRxiv, 2022.2001.2017.22269201, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.17.22269201

Emmenegger, M. et al. Both COVID-19 infection and vaccination induce high-affinity cross-clade responses to SARS-CoV-2 variants. iScience. 25, 104766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.104766 (2022).

Convalescent plasma in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A randomised controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 397, 2049–2059. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00897-7 (2021).

Joyner, M. J. et al. Effect of Convalescent plasma on mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: initial three-Month experience. Preprint MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.12.20169359 (2020).

Agarwal, A. et al. Convalescent plasma in the management of moderate covid-19 in adults in India: open label phase II multicentre randomised controlled trial (PLACID Trial). Bmj. 371https://doi.org/10.1136/Bmj.m4232 (2020).

Sullivan, D. J. et al. Early Outpatient Treatment for Covid-19 with Convalescent plasma. N Engl. J. Med.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2119657 (2022).

Wouters, E. et al. Intranasal administration of convalescent plasma protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters. EBioMedicine.92, 104597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104597 (2023).

Leeman, M. et al. Proteins and antibodies in serum, plasma, and whole blood-size characterization using asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation (AF4). Anal. Bioanal Chem.410, 4867–4873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-018-1127-2 (2018).

Kirkeby, L. et al. Immunoglobulins in nasal secretions of healthy humans: structural integrity of secretory immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1) and occurrence of neutralizing antibodies to IgA1 proteases of nasal bacteria. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol.7, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1128/cdli.7.1.31-39.2000 (2000).

Kubagawa, H. et al. Analysis of paraprotein transport into the saliva by using anti-idiotype antibodies. J. Immunol.138, 435–439 (1987).

Scicchitano, R., Husband, A. J. & Cripps, A. W. Immunoglobulin-containing cells and the origin of immunoglobulins in the respiratory tract of sheep. Immunology. 52, 529–537 (1984).

Shoham, S. et al. Transfusing Convalescent plasma as Post-exposure Prophylaxis against severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a Double-Blinded, phase 2 Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis.76, e477–e486. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac372 (2022).

Focosi, D. & Franchini, M. Polyclonal immunoglobulins for COVID-19 pre-exposure prophylaxis in immunocompromised patients. Transfus. Apher Sci.62, 103648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2023.103648 (2023).

Qi, H. et al. The humoral response and antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol.23, 1008–1020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-022-01248-5 (2022).

Gharbharan, A. et al. Effects of potent neutralizing antibodies from convalescent plasma in patients hospitalized for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun.12, 3189. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23469-2 (2021).

Casarola, G. et al. Efficacy of convalescent plasma therapy in immunocompromised patients with COVID-19: a case report. Clin. Infect. Pract.12, 100096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinpr.2021.100096 (2021).

Van Damme, K. F. A. et al. Case Report: convalescent plasma, a targeted therapy for patients with CVID and severe COVID-19. Front. Immunol.11, 596761. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.596761 (2020).

Bar, K. J. et al. A randomized controlled study of convalescent plasma for individuals hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. J. Clin. Investig.131https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI155114 (2021).

Misset, B. et al. Convalescent plasma for Covid-19-Induced ARDS in mechanically ventilated patients. N Engl. J. Med.389, 1590–1600. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2209502 (2023).

Tang, J. et al. Antibody affinity maturation and plasma IgA associate with clinical outcome in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Nat. Commun.12, 1–13 (2021).

Dzimianski, J. V. et al. Rapid and sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies by biolayer interferometry. Sci. Rep.10, 21738. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78895-x (2020).

Schneider, M. M. et al. Microfluidic characterisation reveals broad range of SARS-CoV-2 antibody affinity in human plasma. Life Sci. Alliance. 5, e202101270. https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa.202101270 (2022).

WHO International Standard (NIBSC code. 20/136): Instructions for use. Version 2.0. Natl. Inst. Biol. Stand. Control. https://www.nibsc.org/documents/ifu/20-136.pdf (2020).

Nguyen, D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibody testing in Europe: towards harmonisation of neutralising antibody titres for better use of convalescent plasma and comparability of trial data. Eurosurveillance. 26, 2100568. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.27.2100568 (2021).

WHO International Standard (NIBSC code. 21/338): instructions for use. Version 2.0. Natl. Inst. Biol. Stand. Control. https://www.nibsc.org/documents/ifu/21-338.pdf (2022).

Stevens, F. J. & Bobrovnik, S. A. Deconvolution of antibody affinities and concentrations by non-linear regression analysis of competitive ELISA data. J. Immunol. Methods. 328, 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2007.08.007 (2007).

Friguet, B. et al. Measurements of the true affinity constant in solution of antigen-antibody complexes by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Immunol. Methods. 77, 305–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(85)90044-4 (1985).

Ali, M. Y. Histology of the human nasopharyngeal mucosa. J. Anat.99, 657–672 (1965).

Beule, A. G. Physiology and pathophysiology of respiratory mucosa of the nose and the paranasal sinuses. GMS Curr. Top. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.9, Doc07. https://doi.org/10.3205/cto000071 (2010).

Gizurarson, S. The relevance of nasal physiology to the design of drug absorption studies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.11, 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-409X(93)90015-V (1993).

Widdicombe, J. H. Regulation of the depth and composition of airway surface liquid. J. Anat.201, 313–318. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00098.x (2002).

Fahy, J. V. & Dickey, B. F. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N Engl. J. Med.363, 2233–2247. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0910061 (2010).

Mercer, R. R. et al. Cell number and distribution in human and rat airways. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol.10, 613–624. https://doi.org/10.1165/ajrcmb.10.6.8003339 (1994).

Knudsen, L. & Ochs, M. The micromechanics of lung alveoli: structure and function of surfactant and tissue components. Histochem. Cell. Biol.150, 661–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-018-1747-9 (2018).

Gil, J. et al. Alveolar volume-surface area relation in air- and saline-filled lungs fixed by vascular perfusion. J. Appl. Physiol.47, 990–1001. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1979.47.5.990 (1979).

Acknowledgements

We thank all donors who have voluntarily donated (convalescent) plasma. We thank the Belgian Red Cross-Flanders employees who have participated in recruitment, plasma collection, component manufacturing, CCP distribution, and quality assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic. We thank Prof. Dr. Piet Maes for the execution and analyzation of the PRNT data. We thank Prof. Dr. Lieven De Lathauwer and Raphaël Widdershoven for the design of the apparent affinity ELISA application. We thank Dr. Chanice Knight for her contribution in determining the neutralization titres with the microneutralization assay.

Funding

Flanders Innovation & Entrepreneurship (VLAIO) (to C.V., E.W., R.D., H.B.F. and V.C.), the Foundation for Scientific Research of the Belgian Red Cross Flanders (to C.V., E.W., R.D., H.B.F., V.C., S.S. and D.D.B.) and Magnus Ehrnrooth Foundation (to V.N.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VC, HBF and EW coordinated the study. EW, HBF and CV designed the study. CV, EW and RD performed laboratory experiments and data collection. HH and VN performed and analysed the microneutralization assay experiments. DDB and SS performed biobanking operations. HBF, EW and CV performed data interpretation. CV performed statistical analysis. HBF and CV drafted the manuscript. All authors edited the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verbrugghe, C., Wouters, E., Devloo, R. et al. Biochemical rationale for transfusion of high titre COVID-19 convalescent plasma. Sci Rep 14, 23579 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75093-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75093-x