Abstract

The rapid response system (RRS) is associated with a reduction in in-hospital mortality. This study aimed to determine the characteristics and outcomes of patients transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) by a rapid response team (RRT). This retrospective, multicenter cohort study included patients from nine hospitals in South Korea. Adult patients who were admitted to the general ward (GW) and required RRS activation were included. Patients with do-not-resuscitate orders and without lactate level or Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score were excluded. A total of 8228 patients were enrolled, 3379 were transferred to the ICU. The most common reasons for RRT activation were respiratory distress, sepsis and septic shock. The number of patients who underwent interventions, the length of hospital stays, 28-day mortality, and in-hospital mortality were higher in the ICU group than in the GW group. Factors that could affect both 28-day and in-hospital mortality included the severity score, low PaO2/FiO2 ratio, higher lactate and C-reactive protein levels, and hospitalization time prior to RRT activation. Patients admitted to the ICU after RRT activation generally face more challenging clinical situations, which may affect their survival outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The rapid response system (RRS) is designed to improve safety by reducing rescue failures due to delayed or incorrect medical management of patients in deteriorating general wards 1,2. The system is activated by vital signs, scoring systems, and direct calls from physicians or nurses 3,4,5. Activated patients receive interventions such as oxygen supplementation, airway management, central vascular line insertion, and resuscitation. If necessary, they are transferred to an intensive care unit (ICU) for critical care, if necessary 1. A previous meta-analysis showed that rapid response systems may be associated with reduced in-hospital mortality 6.

In previous studies, approximately 20–40% of patients with an activated rapid response team (RRT) were transferred to the ICU and received interventions such as endotracheal intubation, vasopressors, central venous access, or hemodynamic monitoring 7,8,9,10,11. However, little research has been conducted on the characteristics of patients transferred to the ICU. We previously conducted a single-center, retrospective study of the characteristics of patients transferred to the ICU after RRT screening and intervention 12. Patients transferred to the ICU had higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores, National Early Warning Scores (NEWS), and lactate levels. Although the first study included approximately 1000 patients, it was limited by its single-center design. Therefore, in the current study, we aimed to identify the characteristics of patients transferred to the ICU using a multicenter cohort.

Results

Patients’ baseline characteristics

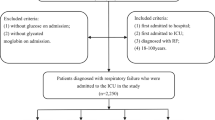

A total of 12,803 patients were screened for RRT during the study period and 4,575 patients were excluded (Fig. 1). Of the 8,228 patients included, 4,849 (58.9%) remained on the general ward (GW) and 3,379 (41.1%) were transferred to the ICU. Patients who were transferred to the ICU were younger (64.3 ± 14.5 vs. 65.6 ± 14.8, P < 0.001) and had a higher proportion of female than the group who remained in the GW (62.9% vs.57.4%, P < 0.001). The proportion of patients diagnosed with solid tumors within 5 years (32.3% vs. 38.5%, P < 0.001) and patients with chronic lung disease (12.8% vs. 15.8%, P < 0.001) was higher in the GW group than in the ICU group. In contrast, the number of patients with hematologic malignancy (12.6% vs. 10.7%, P < 0.007), cardiovascular disease (26.9% vs. 23.0%, P < 0.001), chronic kidney disease (12.1% vs. 10.3%, P = 0.013), and organ transplantation (5.2% vs. 3.6%, P = 0.001) was higher in the ICU group than in the GW group.

The vital signs recorded at the time of initial RRT screening indicated lower mean arterial pressure (MAP, 80.6 ± 27.7 vs. 83.3 ± 21.5, P < 0.001), and SpO2 (90.6 ± 13.6 vs. 93.1 ± 8.0, P < 0.001), and a higher heart rate (HR, 105.9 ± 32.8 vs. 103.2 ± 27.5, P < 0.001), and respiratory rate (RR, 24.5 ± 8.7 vs. 23.3 ± 6.8, P < 0.001) in patients who transferred to the ICU than in those who remained in the GW. The MEWS (5.0 ± 2.4 vs. 3.9 ± 2.0, P = 0.001), NEWS2 (8.8 ± 3.3 vs. 7.1 ± 3.0, P < 0.001), and SOFA scores (6.6 ± 3.6 vs. 4.3 ± 2.8, P < 0.001), which are early warning scores, were higher in the ICU group than in the GW group. On the laboratory analysis, pH (7.43 [7.38–7.47] vs. 7.41 [7.32–7.46], P < 0.001), and hemoglobin levels (9.8 [8.4–11.5] vs. 10.0 [8.7–11.5] g/dL, P = 0.002) were lower in the ICU group than in the GW group. However, the white blood cell count (WBC, 10.41 [6.34–15.40] vs. 9.60 [6.40–14.0] \(\:\times\:\)103/µL, P < 0.001), and lactate level (2.40 [1.40–4.50] vs. 1.70 [1.16–2.88] mEq/L, P < 0.001) were higher in the ICU group than in the GW group. In addition, patients admitted to the ICU had a longer hospitalization time prior to RRT activation than those who were not (6 [2–16] vs. 4 [1–2] days; P < 0.001). There were no significant between-group differences in terms of other characteristics (Table 1).

Intervention and outcomes

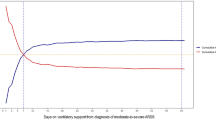

Table 2 shows the interventions and outcomes of the screened patients. Respiratory distress was the most common cause of RRT activation (38.0%), followed by sepsis and septic shock (10.7%). In the GW group, the reasons for RRT activation were arrhythmia (6.7%), hypovolemic shock (4.9%), and cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock (1.9%). In the ICU group, the reasons for RRT activation were hypovolemic shock (8.6%), cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock (8.0%), and arrhythmia (4.5%). In addition, the rate of RRT intervention was significantly higher rate for patients who were transferred to the ICU than that for those who were not, across all interventional procedures. Length of hospital stay was longer in the ICU group than in the GW group (29 [16–55] vs. 21 [11–38] days, P < 0.001); 28-day mortality (n = 1,689 (26.7%) vs. n = 786 (16.2%), P < 0.001, Fig. 2) and in-hospital mortality (n = 1,157 (34.3%) vs. n = 979 (20.2%), P < 0.001) were also significantly higher in the ICU group than in the GW group.

Factors associated with ICU transfer and mortality

Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate analysis performed to identify factors influencing ICU transfer. In this analysis, younger age (odds ratio, OR; 0.996; 95% CI, 0.992–1.000; P = 0.048), female sex (OR, 0.810; 95% CI,0.720–0.911; P < 0.001), high MEWS score (OR, 1.225; 95% CI, 1.185–1.266; P < 0.001), low HR (OR, 0.997; 95% CI,0.994–0.999; P = 0.012), no diagnosis of solid tumors within 5 years (OR, 0.707; 95% CI, 0.624–0.802; P < 0.001), no history of chronic lung disease (OR, 0.765; 95% CI, 0.644–0.908; P = 0.002), low pH (OR,0.070; 95% CI, 0.037–0.122; P < 0.001), low P/F ratio (OR, 0.997; 95% CI, 0.996–0.997; P < 0.001), and high total bilirubin (OR,1.017; 95% CI, 1.004–1.030; P = 0.012), high creatinine (OR, 1.071; 95% CI, 1.034–1.110; P < 0.001), high lactate levels (OR, 1.113; 95% CI, 1.086–1.141; P < 0.001), and longer duration of hospitalization before RRT activation (OR, 1.004; 95% CI, 1.001–1.007; P = 0.013) were indicated as independent factors for ICU transfer.

In addition, multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed on the factors associated with 28-day mortality (Table 4). In this analysis, high MEWS score, high RR, diagnosis of solid tumors, diagnosis of hematologic malignancy, low pH, low P/F ratio, high WBC count, low platelet count, high total bilirubin, high lactate level, high C-reactive protein (CRP) level, ICU transfer after RRT activation, and longer duration of hospitalization before RRT activation were shown to be independent predictors of 28-day mortality. The results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis of the factors that could affect in-hospital mortality are shown in Table 5. The results were similar for 28-day mortality, but older age, chronic lung disease, no cardiovascular disease, no history of transplantation, and shorter duration of hospitalization before RRT activation was considered an additional risk factor for in-hospital mortality.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the characteristics of patients transferred to the ICU using a multicenter cohort. In this study, 41.1% of the patients selected for RRT were transferred to the ICU. Patients who were younger; female; or did not have solid tumors, hematologic malignancies, or chronic lung disease were more likely to be admitted to the ICU after RRT activation. In addition, patients admitted to the ICU had an in-hospital mortality rate of 34.3%. Factors associated with patient mortality included older age, high inflammatory markers, solid tumors, hematologic malignancies, chronic lung disease, and no history of cerebrovascular disease, or transplantation. Multivariate analysis suggests a possible association between ICU admission and increased risk of 28-day mortality, although this was not reflected in in-hospital mortality rates.

In our study, the ICU group had a higher rate of activation due to respiratory distress, sepsis, cardiac arrest, and various types of shock (Table 2). These findings are consistent with those of several previous studies 13,14,15,16 and support the notion that ICU patients experience multiple physiological instabilities 17. In addition, the ICU group underwent more frequent interventions such as central line insertion, intubation, and vasopressor administration compared to the GW group. These procedures are critical in managing conditions such as shock or respiratory failure, which are common reasons for initiating interventions in the ICU setting 9,13,18,19. Follow-up care is less complicated when interventions are implemented quickly 15,20. A meta-analysis published in 2015 showed an overall reduction in in-hospital mortality after RRS (RR 0.87, 95%CI 0.81–0.95, P < 0.001) 6. There is also evidence that RRT is associated with improved outcomes 21,22. Therefore, early intervention with RRT may be important to optimize patient management and outcomes.

In several other studies, approximately 20–40% of patients with activated RRT were transferred to the ICU 7,8,9,10,11, results which are similar to those of our study. Our previous study showed that factors influencing ICU admission included high disease severity, as indicated by high SOFA and NEWS scores 12. In the multivariate analysis performed in this study, in addition to factors indicating disease severity, younger age, no malignancy, and no history of chronic lung disease were identified as influencing factors. In some studies, older patients were admitted to the ICU with worse outcomes, such as 1-year mortality 23,24,25. Our results also showed that advanced age was a cause of increased in-hospital mortality, which could be attributed to the decision to transfer younger patients with a higher chance of survival to the ICU for critical care. In addition, patients with a history of cancer have a higher mortality rate 26; when patients with malignancies are admitted to the ICU, their mortality rate is approximately 40%, which is even higher in the case of hematological malignancies 27,28. In a meta-analysis conducted by Huapaya et al. 29, the in-hospital mortality of patients with various types of interstitial lung disease (ILD) was 52%. In addition, Brown et al. 30 showed that patients with ILD or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have a longer ICU stay than cancer patients. As these factors, like age, are associated with in-hospital mortality, these prognostically relevant factors have been shown to influence the decision to admit patients to the ICU.

The factors associated with in-hospital mortality were not significantly different from those reported in our previous single-center study 12. In this study, the risk factors for in-hospital mortality were older age, higher SOFA, NEWS2, lactate level, CRP level, WBC count, history of solid tumors, hematologic malignancy, and chronic lung disease. History of solid tumors, hematologic malignancies, and chronic lung disease are indicators of poor outcome 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. In a study conducted in 2018, to build a mortality prediction model for patients with RRT calls, systolic blood pressure (SBP), time from admission to RRT call, and RR were suggested as factors predicting mortality 20, which showed results consistent with our analysis. However, in our study, a low MEWS score was found to be a factor in the two death-related outcomes. MEWS has already been widely used as an early warning score and it is useful in predicting in-hospital outcomes 31,32. A meta-analysis published by Suwanpasu et al. 33 showed that the MEWS threshold of 4 or more had reasonable accuracy for predicting in-hospital death. In addition, the mean MEWS score of deceased patients was 3.5–4.5 34,35. Our results showed a mean MEWS score of 4.4 ± 2.2, with the ICU group having a higher mean of 5.0 ± 2.4. This suggests that patients in our study were more critically ill at the time of assessment compared to general predictions. Transfer to the ICU appeared to be associated with an increased risk of 28-day mortality, but it did not show a significant risk for in-hospital mortality. A previous study aimed at developing a model to predict patient outcomes in the ICU found that while some patients experience an increasing hazard over time, others who survive the initial period, despite a high initial hazard, transition to a group with a lower hazard36. Additionally, Poole et al. conducted a study on elderly patients admitted to the ICU, which indicated that early acute-phase management is crucial, while chronic conditions become the primary cause of mortality over the long term37. Consequently, although the severity of patients admitted to the ICU may lead to higher early mortality rates, appropriate treatment can mitigate this risk, suggesting that ICU admission itself may not be a direct indicator of increased mortality.

This study has several limitations. First, our analysis was limited to evaluating the causes at the time of RRT activation, without considering additional complications or diagnoses that occurred after the patient was transferred to the ICU. Second, the inclusion criteria were limited to patients evaluated for RRT, excluding those who were admitted directly to the ICU or were unavailable, which may have introduced selection bias. Third, although there were variations among centers in patient demographics, RRT activation criteria, and timing of interventions, this multicenter retrospective cohort study utilized a large patient database. However, despite being conducted across tertiary hospitals, differences in patient severity and other factors led to reliance on the clinical judgment of individual clinicians, making it difficult to establish a uniform set of criteria across all hospitals. Additionally, the retrospective nature of the study made it challenging to predefine consistent criteria. This provides a broad perspective of most RRT-activated patients, although it may not fully capture the nuances of individual center practices and patient populations.

Conclusion

Our study showed that younger age and higher severity scores were predictive of ICU transfer, whereas older age and chronic diseases, such as malignancy, were predictive of in-hospital mortality. Multivariate analysis showed that ICU transfer after RRT activation did not have a significant impact on outcomes. Our findings suggest that more individualized patient assessments are needed to optimize ICU admission and interventions; this may improve patient care and survival outcomes.

Methods

Study design and population

This multicenter, retrospective cohort study was conducted at nine tertiary or university-affiliated hospitals in South Korea between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2017. The steering committee developed the study protocol, periodically reviewed the progress of the study, and provided overall oversight. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of each participating hospital (Chungnam national university hospital, Chungnam national university hospital IRB, approval number: CUNH 2019-06-030; in Asan medical center, Asan medical center IRB: 2019 − 0469; Inha university hospital, Inha university hospital, approval number: INHAUH 2019-04-008, in Dong-A university hospital, Dong-A university hospital IRB: DAUHIRB-19-107; Samsung medical center, Samsung medical center IRB, approval number: SMC 2019-04-150; CHA Bundang medical center, CHA Bundang medical center IRB, approval number: CHAMC 2019-03-059; Ulsan university hospital, Ulsan university hospital IRB, approval number: UUH 2019-08-024; Seoul national university Bundang hospital, Seoul national university Bundang hospital IRB, approval number: B-1904/535 − 105; Seoul national university hospital, Seoul national university hospital IRB, approval number: J-2010-062-1163). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guideline and regulation. The requirement for informed consent was waived in all participating centers (Chungnam national university hospital, Asan medical center, Inha university hospital, Dong-A university hospital, Samsung medical center, CHA Bundang medical center, Ulsan university hospital, Seoul national university Bundang hospital, Seoul national university hospital) because of the retrospective nature of the study and the use of anonymized patient data.

Rapid response team

At each hospital, all adult patients aged ≥ 19 years who were admitted to the general ward (GW) and required RRS activation were included. Using electronic medical records (EMRs), patients who met the screening criteria established at each center were screened and activated. The nine hospitals involved in the study employed somewhat varied screening criteria. Six hospitals utilized a single-parameter trigger system, two hospitals implemented the MEWS or NEWS, and one hospital combined a single-parameter trigger system with NEWS. A range of single parameters, such as abnormal blood pressure, elevated or decreased respiratory rate, tachycardia or bradycardia, abnormal body temperature, oxygen desaturation detected by pulse oximetry, neurological decline, threatened airway, lactic acidosis, abnormal blood gas analysis results such as hypercapnia, and metabolic acidosis can also trigger the RRT (Supplementary file 1). Patients with a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and those without lactate levels or SOFA scores at the time of activation were excluded. Patients were grouped according to whether they remained in the GW or were transferred to the ICU after RRT activation.

Data collection

In every participating center, the certified study coordinators reviewed the electronic medical records of each patient, and the data were gathered consistently across all centers according to a standardized format. The standardized report form for all centers was used to collect data on demographic characteristics, comorbidities, vital signs, oxygen saturation, RRS activation, and patient outcomes such as in-hospital mortality and length of hospital stay. RRS activation means that the RRS medical staff identifies screened patients according to the criteria of each hospital and implements the necessary interventions and recommendations. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores have been used to predict mortality during the first 24 h of ICU admission 38. The National Early Warning Score (NEWS) has been used to assess acute illness and to determine response 5,39. In addition, the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), which can easily and quickly screen for patients requiring bedside intervention, was used 3. The reason for RRT screening was determined by referring to the test results at the time of the initial RRT screening, patient history, and vital signs. All the participating centers were requested to complete data entries and email the data to the coordination center, where the quality of the data was evaluated for completeness and for logical errors. And all methods were conducted following the appropriate guidelines and regulations.

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as percentage for categorical variables. Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used to examine continuous data, and chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with ICU transfer, and Cox regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with 28-day and in-hospital mortality. In addition, variables with P < 0.1 in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate models. We used Spearman correlation to analyze the relationships between variables intended for use in logistic and Cox regression analysis. IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM, Armonk, New York, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses; statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

DeVita, M. A. et al. Findings of the first consensus conference on medical emergency teams. Crit. Care Med. 34, 2463–2478 (2006).

Jones, D. A., DeVita, M. A. & Bellomo, R. Rapid-response teams. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 139–146 (2011).

Subbe, C. P., Kruger, M., Rutherford, P. & Gemmel, L. Validation of a modified early warning score in medical admissions. Qjm. 94, 521–526 (2001).

Lee, B. Y. & Hong, S. B. Rapid response systems in Korea. Acute Crit. Care. 34, 108–116 (2019).

Smith, G. et al. The national early warning score 2 (NEWS2). Clin. Med. 19 (2019).

Maharaj, R., Raffaele, I. & Wendon, J. Rapid response systems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care. 19, 1–15 (2015).

Karpman, C. et al. The impact of rapid response team on outcome of patients transferred from the ward to the ICU: A single-center study. Crit. Care Med. 41, 2284–2291 (2013).

Tirkkonen, J., Tamminen, T. & Skrifvars, M. B. Outcome of adult patients attended by rapid response teams: A systematic review of the literature. Resuscitation. 112, 43–52 (2017).

Lyons, P. G., Edelson, D. P. & Churpek, M. M. Rapid response systems. Resuscitation. 128, 191–197 (2018).

Lee, J. et al. Impact of hospitalization duration before medical emergency team activation: a retrospective cohort study. Plos One. 16, e0247066 (2021).

Park, J. et al. The association between hospital length of stay before rapid response system activation and clinical outcomes: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Respir. Res. 22, 1–10 (2021).

Lee, S. I., Koh, J. S., Kim, Y. J., Kang, D. H. & Lee, J. E. Characteristics and outcomes of patients screened by rapid response team who transferred to the intensive care unit. BMC Emerg. Med. 22, 1–8 (2022).

Chan, P. S. et al. Hospital-wide code rates and mortality before and after implementation of a rapid response team. Jama. 300, 2506–2513 (2008).

Jung, B. et al. Rapid response team and hospital mortality in hospitalized patients. Intensive Care Med. 42, 494–504 (2016).

Silva, R., Saraiva, M., Cardoso, T. & Aragão, I. C. Medical emergency team: how do we play when we stay? Characterization of MET actions at the scene. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 24, 1–6 (2016).

Boniatti, M. M. et al. Association between time of day for rapid response team activation and mortality. J. Crit. Care. 77, 154353 (2023).

Bellomo, R. et al. A prospective before-and‐after trial of a medical emergency team. Med. J. Aust. 179, 283–287 (2003).

Myrskykari, H., Iirola, T. & Nordquist, H. The role of emergency medical services in the management of in-hospital emergencies: causes and outcomes of emergency calls–A descriptive retrospective register-based study. Australasian Emerg. Care (2023).

Evans, L. et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit. Care Med. 49, e1063–e1143 (2021).

Shappell, C., Snyder, A., Edelson, D. P., Churpek, M. M. & American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators. Predictors of in-hospital mortality after rapid response team calls in a 274 hospital nationwide sample. Crit. Care Med. 46, 1041–1048 (2018).

Al-Omari, A., Al Mutair, A. & Aljamaan, F. Outcomes of rapid response team implementation in tertiary private hospitals: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 12, 1–5 (2019).

Al-Qahtani, S. et al. Impact of an intensivist-led multidisciplinary extended rapid response team on hospital-wide cardiopulmonary arrests and mortality. Crit. Care Med. 41, 506–517 (2013).

Fuchs, L. et al. ICU admission characteristics and mortality rates among elderly and very elderly patients. Intensive Care Med. 38, 1654–1661 (2012).

Wunsch, H. et al. Three-year outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries who survive intensive care. Jama. 303, 849–856 (2010).

Tabah, A. et al. Quality of life in patients aged 80 or over after ICU discharge. Crit. Care. 14, 1–7 (2010).

Brenner, H. Long-term survival rates of cancer patients achieved by the end of the 20th century: A period analysis. Lancet. 360, 1131–1135 (2002).

Assi, H. I. et al. Outcomes of patients with malignancy admitted to the intensive care units: A prospective study. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2021 (2021).

Vijenthira, A. et al. Predictors of intensive care unit admission in patients with hematologic malignancy. Sci. Rep-Uk. 10, 21145 (2020).

Huapaya, J. A., Wilfong, E. M., Harden, C. T., Brower, R. G. & Danoff, S. K. Risk factors for mortality and mortality rates in interstitial lung disease patients in the intensive care unit. Eur. Respir. Rev. 27 (2018).

Brown, C. E., Engelberg, R. A., Nielsen, E. L. & Curtis, J. R. Palliative care for patients dying in the intensive care unit with chronic lung disease compared with metastatic cancer. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 13, 684–689 (2016).

Cei, M., Bartolomei, C. & Mumoli, N. In-hospital mortality and morbidity of elderly medical patients can be predicted at admission by the modified early warning score: a prospective study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 63, 591–595 (2009).

Mitsunaga, T. et al. Comparison of the National Early warning score (NEWS) and the modified early warning score (MEWS) for predicting admission and in-hospital mortality in elderly patients in the pre-hospital setting and in the emergency department. PeerJ. 7, e6947 (2019).

Suwanpasu, S. & Sattayasomboon, Y. Accuracy of modified early warning scores for predicting mortality in hospital: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Intensive Crit. Care. 2, 29 (2016).

Cattermole, G. N. et al. Derivation of a prognostic score for identifying critically ill patients in an emergency department resuscitation room. Resuscitation. 80, 1000–1005 (2009).

Ghanem-Zoubi, N. O., Vardi, M., Laor, A., Weber, G. & Bitterman, H. Assessment of disease-severity scoring systems for patients with sepsis in general internal medicine departments. Crit. Care. 15, 1–7 (2011).

Moreno, R. P. et al. Modeling in-hospital patient survival during the first 28 days after intensive care unit admission: a prognostic model for clinical trials in general critically ill patients. J. Crit. Care. 23, 339–348 (2008).

Poole, D. et al. Differences in early, intermediate, and long-term mortality among elderly patients admitted to the ICU: Results of a retrospective observational study. Minerva Anestesiol. 88, 479–489 (2022).

Vincent, J. L. et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med. 22, 707–710 (1996).

RCoP, L. & National Early Warning Score (NEWS). Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Report of Working Party (Royal College of Physicians, London, 2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Funding

This work was supported by research fund of Chungnam National University (No. 2023 − 0543). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YN and SIL conceived and designed the study; BJK, SBH, KJ, DHL, JSK, JP, SML and SIL participated in creating case report form and data collection; YN, BJK, SBH, KJ, DHL, JSK, JP, SML and SIL analyzed and interpreted the data; YN and SIL drafted the manuscript for intellectual content; YN, BJK, SBH, KJ, DHL, JSK, JP, SML and SIL revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nam, Y., Kang, B.J., Hong, SB. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients screened by the rapid response team and transferred to intensive care unit in South Korea. Sci Rep 14, 25061 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75432-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75432-y