Abstract

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a widespread endocrinological dysfunction impacting women of reproductive age, categorized by excess androgens and a variety of associated syndromes, consisting of acne, alopecia, and hirsutism. It involves the presence of multiple immature follicles in the ovaries, which can disrupt normal ovulation and lead to hormonal imbalances and associated health complications. Routine diagnostic methods rely on manual interpretation of ultrasound (US) images and clinical assessments, which are time-consuming and prone to errors. Therefore, implementing an automated system is essential for streamlining the diagnostic process and enhancing accuracy. By automatically analyzing follicle characteristics and other relevant features, this research aims to facilitate timely intervention and reduce the burden on healthcare professionals. The present study proposes an advanced automated system for detecting and classifying PCOS from ultrasound images. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) based techniques, the system examines affected and unaffected cases to enhance diagnostic accuracy. The pre-processing of input images incorporates techniques such as image resizing, normalization, augmentation, Watershed technique, multilevel thresholding, etc. approaches for precise image segmentation. Feature extraction is facilitated by the proposed CystNet technique, followed by PCOS classification utilizing both fully connected layers with 5-fold cross-validation and traditional machine learning classifiers. The performance of the model is rigorously evaluated using a comprehensive range of metrics, incorporating AUC score, accuracy, specificity, precision, F1-score, recall, and loss, along with a detailed confusion matrix analysis. The model demonstrated a commendable accuracy of \(96.54\%\) when utilizing a fully connected classification layer, as determined by a thorough 5-fold cross-validation process. Additionally, it has achieved an accuracy of \(97.75\%\) when employing an ensemble ML classifier. This proposed approach could be suggested for predicting PCOS or similar diseases using datasets that exhibit multimodal characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome is a disorder that affects a large number of women worldwide. It causes ovaries to produce a high number of immature eggs, which turn into cysts, leading to enlarged ovaries and increased androgen production1,2. PCOS was first identified by Stein and Leventhal in 19353, characterized by symptoms such as hirsutism, chronic amenorrhea, anovulation, and enlarged ovarian cysts etc. Although Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome was recognized earlier, it wasn’t officially included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) by the World Health Organization under the code ’E28.2’ until 19904. In 2009, the definition of PCOS was revised to include hyperandrogenism. Hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovary morphology (PCOM)5 are fundamental aspects of PCOS, a condition of ovarian dysfunction6. PCOM is defined by an ovarian volume of 10 ml or 25 follicles per ovary with 8 MHz transducer frequencies. Among the innumerable health challenges faced by women in the 21st century7, PCOS has emerged as a prevalent and significant concern impacting women of reproductive age (18–44). Approximately one in fifteen women worldwide are affected by PCOS8,9, with prevalence rates in India ranging from 3.7 to 22.5%, higher in urban areas than rural areas10, possibly due to lifestyle factors and stress11. Estimates suggest that approximately 120 million women, or 4.4% of the global female population, are affected by PCOS. In India, Ramamoorthy et al.12 found that 10% of young girls suffer from PCOS, which is associated with a high rate of miscarriages and infertility cases10. It is linked to various psychological and metabolic issues, including hirsutism, irregular menstrual cycles, sudden weight gain, thyroid issues, type 2 diabetes, depression, excessive hair growth, alopecia, oily skin, acne, high blood pressure, sexual dissatisfaction2,13,14, and metabolic issues such as hypertension, hyperinsulinemia, abdominal obesity, and dyslipidemia, all of which diminish the quality of life. A family history of PCOS significantly increases the risk, with 24%-32% of patients likely to develop the condition15. It can also lead to cancers in the breast16 or uterus during reproductive age. Low follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels combined with high prolactin levels prevent follicle growth and maturation in ovaries afflicted by PCOS. Normally, with the right levels of FSH and LH, a single follicle grows to about 20 mm in diameter and is ready for ovulation17. In polycystic ovaries, follicles stop growing at 5–7 mm during ovulation and remain immature. These immature follicles secrete a hormone that thickens the uterine lining, leading to spotting or excessive bleeding due to prolonged estrogen production.

However, early diagnosis through standardized approaches can lead to effective management with long-term, symptom-focused treatments. Due to these varied criteria, diagnosing PCOS is challenging, but the Rotterdam criteria18 are a widely accepted method. According to the Rotterdam Consensus Criteria (2003)19, PCOS is diagnosed if at least two of the specified criterias are met; the measures are oligo-anovulation, clinical or biochemical signs of excess androgen activity, if the ovaries have a volume of at least 10 \(\hbox {cm}^{3}\) or contain 10 or more follicles i.e. polycystic overies. Ultrasound diagnostics use frequencies between 2 and 15 MHz, with sound waves sent to the object and reflected back as electrical pulses displayed as grayscale images. The high noise and low contrast of US images necessitate better accuracy to detect Polycystic Ovary follicles, which appear spherical and clustered in a necklace-like pattern. In contrast, in 2006 the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society required the presence of hyperandrogenemia, ovulation disorder, and PCOM for diagnosis4. Each diagnostic criterion has distinct clinical implications, such as skin manifestations from excessive androgen, endometrial hyperplasia, infertility from ovulation disorders, and risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) from PCOM. Ultrasound imaging is a primary tool for early detection of PCOS20, providing vital information on the number, volume, and position of follicles. Ultrasound is preferred over CT and MRI due to its low cost, accessibility, safety, and real-time results21,22, but it is time-consuming, prone to human error, and reliant on the availability of skilled radiologists, particularly in less developed regions. Consequently, many women remain undiagnosed and untreated. These challenges underscore the need for intelligent computer-aided systems to support gynecologists, traditional methods, which involve image processing and machine learning, are complex and less effective, while deep learning methods, despite their accuracy and overcoming manual examination limitations, are computationally demanding1,23,24, also an integrated machine learning approach could improve diagnostic performance and reduce the computational complexity of identifying PCOS from ultrasound images25. In contrast, AI-based approaches are showing promising results in other ultrasound imaging26 applications, such as thyroid27,28,29 , breast cancer detection30 , etc., further enhancing diagnostic accuracy.

Unlike traditional approaches, Haider et al.31 proposed a method that incorporates full contextual information surrounding the face from the provided dataset. Leveraging InceptionNet V3 for deep feature extraction, they employed attention mechanisms to refine these features. Subsequently, the features were passed through transformer blocks and multi-layer perceptron networks to predict various emotional parameters simultaneously. Their model excelled in predicting arousal, valence, emotional expression classification, and action unit estimation, achieving significant performance on the MTL Challenge validation dataset. Aziz et al.32 introduced IVNet, a novel approach for real-time breast cancer diagnosis using histopathological images. Transfer learning with CNN models like ResNet50, VGG16, etc., aims for feature extraction and accurate classification into grades 1, 2, and 3. IVNet achieves a commendable classification rate. Validation and statistical analysis confirm its efficacy. A user-friendly GUI aids real-time cell tracking, facilitating treatment planning. IVNet serves as a reliable decision support system for clinicians and pathologists, specially in resource-constrained settings. The study conducted by Kriti et al.33 evaluated the performance of four pre-trained CNNs named ResNet-18, VGG-19, GoogLeNet, and SqueezeNet for classifying breast tumors in ultrasound images. The proposed CAD system uses GoogLeNet and a convolutional autoencoder for deep feature extraction, followed by correlation-based and fuzzy feature selection, with the final classification done using an ANFC-LH classifier. This system aids radiologists in diagnosis and serves as a training tool for radiology students. A smart feature extraction method based on Convolutional Autoencoders for semiconductor manufacturing was utilized by Maggipinto et al.34, particularly focusing on predicting etch rates using Optical Emission Spectroscopy (OES) data. Traditional Machine Learning algorithms struggle with the complexity of OES data, prompting the adoption of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for feature extraction. The proposed method surpasses conventional techniques like PCA and statistical moments, offering precise etch rate predictions without domain-specific knowledge. Multipath Convolutional Neural Network (M-CNN) for feature extraction and Machine Learning (ML) classifiers for severity classification of Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) using Fundus images was employed by Gayathri et al.35. Evaluation is conducted across multiple databases using Support Vector Machine, Random Forest, and J48 classifiers. Results indicate that the M-CNN network combined with the J48 model performs optimally. The proposed technique offers a promising solution for automated DR diagnosis, with potential applications in predicting other retinal diseases, thus improving retinal healthcare monitoring.

With about 70% of PCOS cases undiagnosed worldwide, Gopalakrishnan et al.36 presented an automated PCOS detection and classification system using ultrasound images. The system preprocesses images with a Gaussian low pass filter, segments them using multilevel thresholding, and extracts features with the GIST-MDR technique, achieving 93.82% accuracy with the Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier. Alamoudi et al.37 conducted a study combining ovarian ultrasound images and clinical data, employing a deep learning model for PCOM detection achieving 84.81% accuracy, and fusion models combining image and clinical data with 82.46% accuracy. The study underscores the importance of clinical data in PCOS detection and highlights the potential of automated models to accelerate diagnosis and mitigate associated risks. An Improved Fruit Fly Optimization-based Artificial Neural Network (IFFOA-ANN) for classifying normal and abnormal follicles in ultrasound images was introduced by Nilofer et al.38, enhancing previous adaptive k-means clustering methods. The technique improves image quality, segments follicles, and extracts features using statistical Grey Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), with the ANN trained on these features. The IFFOA-ANN method achieves 97.5% accuracy, offering a reliable automated classification system that improves the diagnosis and treatment of infertility. Suha39 proposed a hybrid machine-learning method for PCOS detection using 594 ovary ultrasound images. It employs a CNN with transfer learning for feature extraction, specifically the VGGNet16 model, followed by a stacking ensemble model with XGBoost as the meta-learner. This approach effectively combines deep learning and traditional machine learning, outperforming existing techniques in both accuracy and execution time. Maheswari et al.40 conducted a study for PCOS detection using ultrasound images, emphasizing the importance of image processing in improving computer system performance. It employs adaptive histogram equalization to remove noise and extracts features relevant to PCOS. A novel approach called Furious Flies is proposed for feature identification, addressing the drawbacks of conventional algorithms. Three stages—attraction-based ROI selection, follicle selection, and follicle identification—are employed. Classification is performed using a Naive Bayesian classifier and artificial neural networks, enabling early detection of PCOS. Despite these advancements, several gaps remain: the limited dataset sizes, may not represent the full spectrum of PCOS variations, potentially affecting model robustness and generalizability. There is often no discussion on potential biases in the datasets used for training, which could impact model performance on unseen data. Many studies focus on diagnosing specific conditions like PCOM but do not expand to classify other types of ovarian cysts, limiting their clinical utility. Additionally, manual diagnosis of polycystic ovary morphology in ultrasound images by specialists introduces subjectivity and variability, impacting diagnostic accuracy and consistency. Table 1 represents A comprehensive summary of the literature study and its key findings.Addressing these gaps is crucial for developing more robust, generalizable, and clinically useful diagnostic systems. Within the framework of this study, we have introduced several pivotal contributions to advance the domain of deep learning-based image analysis:

-

1.

Image Pre-processing Techniques for Improved Diagnostic Precision The study introduces a comprehensive approach to pre-processing and segmenting ultrasound images for PCOS detection, incorporating multiple techniques such as image resizing, normalization, augmentation, Watershed technique, multilevel thresholding, Morphological Processing etc. This meticulous process ensures precise and accurate identification of follicles and cysts and contributes to the overall diagnostic accuracy, reducing manual errors and time consumption.

-

2.

Innovative Feature Extraction using the CystNet Hybrid Model This proposed CystNet technique for feature extraction is proposed which is a hybrid model that integrates InceptionNet V341,42 and Convolutional Autoencoder43,44deep learning approaches. By leveraging the strengths of both InceptionNet V3, known for its efficiency in handling varied spatial hierarchies, and Autoencoders, which excel in unsupervised learning, CystNet effectively extracts and highlights critical features from ultrasound images. This dual approach enhances the ability of the model to distinguish subtle differences between affected and unaffected cases, thereby improving the reliability and robustness of the diagnostic process.

-

3.

High-Accuracy Classification Using DenseNet and ML Classifiers The classification phase of the proposed system employs a dense Layer or fully connected (FC) layer alongside traditional machine learning classifiers with rigorous 5-fold cross-validation, demonstrating exceptional diagnostic performance.

The remaining study is structured into four sections, each offering a detailed examination of the research process and outcomes. Section 2 details the research methodology, encompassing dataset description, image segmentation, feature extraction, and PCOS classification. Subsequently, Section 3 conducts a thorough analysis of experimental results. Finally, Section 4 encapsulates the key findings of the study and outlines potential future research directions.

Methodology

This section comprises a comprehensive overview of the dataset utilized for training and testing the diagnosis model, followed by image preprocessing which includes normalization, augmentation and segmentation. Moreover, this section discusses the proposed model for diagnosing PCOS using ultrasound images and classifying PCOS and non-PCOS ovaries. The overall framework of this study is visually presented in Fig. 1, outlining the various phases involved in the research.

Dataset description

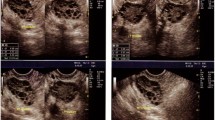

A dataset obtained from Kaggle52 is utilized for training and testing our models, initially comprising 1,924 images for training and 1,932 for testing. However, due to significant overlap between these sets, the test set is discarded, and the training set is utilized exclusively. This set is then split into new training and test sets. It includes ultrasound images labelled as ’INFECTED’ (781 images with cystic ovaries) and ’NOT INFECTED’ (1,143 images with healthy ovaries). The given ’INFECTED’ and ’NOT INFECTED’ classes uniquely identify individuals suffering from PCOS and those who are not, respectively, making this classification method highly relevant for real-time medical systems in accurately diagnosing PCOS. Figure 2 shows sample images from both categories.

This study has also incorporated the PCOSGen Dataset53, gathered from various online sources. This dataset includes 3,200 healthy and 1,468 unhealthy samples, divided into training and test sets, which have been medically annotated by a gynaecologist in New Delhi, India. Additionally, the Multi-Modality Ovarian Tumor Ultrasound (MMOTU) image dataset54 is utilized, containing 1,639 US images from 294 patients.

Dataset preprocessing

The data preprocessing step is crucial for preparing the ultrasound images for training and testing the diagnosis model. It involves several sub-processes: image resizing and normalization, image augmentation, and image segmentation techniques are described below:

Image resizing and normalization

All ultrasound images are resized to a uniform dimension of 224x224 pixels. This standardization ensures that the input dimensions are consistent across all images, which is crucial for the convolutional neural network(CNN) to process them efficiently. Uniform resizing also helps in reducing computational load and memory requirements during model training. After resizing, the pixel values are normalized using min-max normalization55. This involves scaling each pixel value I to a range of 0 to 1 using the formula:

where, I\(\rightarrow\) original pixel value, \(I_{\text {min}}\)\(\rightarrow\) minimum intensity value, and \(I_{\text {max}}\)\(\rightarrow\) maximum intensity value (usually 255 for 8-bit images). This scaling helps in reducing the variance and making the model training process faster and more stable. It also ensures that the pixel values are on a similar scale, preventing any single feature from dominating the learning process.

Image augmentation

Image augmentation56 is essential for enhancing the diversity of training data, thereby improving the ability of the model to generalize and perform well on unseen samples. It includes applying various transformations to the original images, such as rotation, flipping, zooming, and shifting. These operations introduce variations in the dataset, simulating real-world scenarios and ensuring robustness in the predictions of the model. Figure 3 depicts the workings of augmentation operations visually and these augmentation operations are discussed below to provide a comprehensive overview of the transformations applied to the images during the preprocessing stage:

-

Rotation: Images I\(\rightarrow\) rotated by an angle \(\theta\) randomly selected from the range \([-90^\circ , 90^\circ ]\). This transformation is represented mathematically as:

$$\begin{aligned} I_{\text {rotated}} = R(\theta ) \cdot I \end{aligned}$$(2)Where \(R(\theta )\)\(\rightarrow\) rotation matrix for angle \(\theta\).

-

Flipping: Horizontal and vertical flipping are applied, represented as:

$$\begin{aligned} I_{\text {flipped\_horizontal}} = F_h \cdot I \end{aligned}$$(3)$$\begin{aligned} I_{\text {flipped\_vertical}} = F_v \cdot I \end{aligned}$$(4)where \(F_h\) and \(F_v\)\(\rightarrow\) horizontal and vertical flip operators, respectively. This effectively doubles the dataset size.

-

Zooming: Zoom transformations are applied by scaling the image by a factor Z randomly chosen from a range \([Z_{\text {min}}, Z_{\text {max}}]\):

$$\begin{aligned} I_{\text {Zoomed}} = Z(z) \cdot I \end{aligned}$$(5)where Z(z) \(\rightarrow\) zoom transformation matrix.

-

Shifting: Random width \(\Delta _x\) and height \(\Delta _y\) shifts, up to 20% of the total dimensions, are applied:

$$\begin{aligned} I_{\text {shifted}} = T(\Delta _x, \Delta _y) \cdot I \end{aligned}$$(6)Where \(T(\Delta _x, \Delta _y)\)\(\rightarrow\) translation matrix for shifts \(\Delta _x\) and \(\Delta _y\).

Image segmentation

Image segmentation is a crucial process in image analysis, where an image is partitioned into multiple segments or regions to simplify and change the representation of the image into an interpretable format. It is particularly important for medical imaging, as it allows for the precise identification and isolation of relevant structures, such as identifying cysts in ultrasound images for diagnosing PCOS. In this study, the segmentation process involves several steps: noise filtering, contrast enhancement, binarization, multilevel thresholding, and morphological processing. The process used for segmentation is visualized step-by-step in Fig. 4.

-

Noise Filtering: Noise filtering39 aims to smooth out irregularities in the image caused by noise. One common technique is Gaussian blur, which applies a convolution operation between the image and a Gaussian kernel. Mathematically, this is represented as:

$$\begin{aligned} I_{\text {blurred}}(x,y) = \sum _{i=-k}^{k} \sum _{j=-k}^{k} I(x+i, y+j) \times G(i,j) \end{aligned}$$(7)Where i\(\rightarrow\) horizontal distance & j\(\rightarrow\) vertical distance from the center of the kernel, \(I_{\text {blurred}}(x,y)\)\(\rightarrow\) blurred pixel value at coordinates (x, y), \(I(x+i, y+j)\)\(\rightarrow\) neighboring pixel values in the original image, and G(i, j) \(\rightarrow\) Gaussian kernel values which is mathematically represented as:

$$\begin{aligned} G(i,j) = \frac{1}{2\pi \sigma ^2} \exp \left( -\frac{i^2 + j^2}{2\sigma ^2}\right) \end{aligned}$$(8)The Gaussian filter used has a mean of \(\mu = 0\) and a standard deviation of \(\sigma = 0.85\), which are set to specific values during preprocessing to control the amount of smoothing applied.

-

Contrast Enhancement: Contrast enhancement39 techniques aim to improve the visual quality of an image by increasing the intensity differences between pixels. Histogram equalization is a common method that redistributes pixel intensities to achieve a more uniform histogram. Mathematically, the transformation function T is computed from the image histogram H and its cumulative distribution function CDF:

$$\begin{aligned} T(i) = \frac{L-1}{N \times M} \sum _{j=0}^{i} H(j) \end{aligned}$$(9)Where T(i) \(\rightarrow\) transformed intensity value, L\(\rightarrow\) number of intensity levels, and \(N \times M\)\(\rightarrow\) total number of pixels in the image.

-

Watershed Technique: The watershed algorithm40 interprets the intensity gradient of the image as a topographic surface. It identifies regions of unexpected changes in intensity, indicating potential object boundaries. Mathematically, it computes the gradient magnitude \(\nabla I\) of the image and treats it as a topographic surface. It then identifies regions of low intensity and regions of high intensity to segment the image.

-

Binarization: This operation simplifies the image by converting grayscale intensity values to binary values, effectively separating the foreground from the background. Otsu’s thresholding39 is a widely used technique that automatically computes the optimal threshold value T to distinguish between the two classes by minimizing the intra-class variance. The optimal threshold value T is computed by maximizing the between-class variance \(\sigma _B^2\), which represents the variance between the two classes of pixel intensities. Mathematically, it can be expressed as:

$$\begin{aligned} T = \arg \max _t (\sigma _B^2(t)) \end{aligned}$$(10)In this equation, \(\arg \max\)\(\rightarrow\) value of t that maximizes \(\sigma _B^2\) between-class variance.

-

Multilevel Thresholding: Multilevel thresholding36 partitions an image into multiple segments by applying thresholding operations with different threshold values \(T_i\). This technique is useful for segmenting images with complex intensity distributions. Mathematically, it applies thresholding operations with different threshold values \(T_1, T_2, \ldots , T_n\) to segment the image into multiple regions. For a grayscale image, this process can be represented mathematically as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Segment}_i = \{p \in \text {Image} \mid T_{i-1} \le \text {Intensity}(p) < T_i \} \end{aligned}$$(11)Where \(\text {Segment}_i\)\(\rightarrow\) region segmented by the \(i^{th}\) threshold, \(T_{i-1}\) and \(T_i\) are consecutive threshold values, and \(\text {Intensity}(p)\) denotes the intensity of the pixel p in the image.

-

Morphological Processing: Morphological operations39 manipulate the shape and structure of objects in the image. Erosion, dilation, opening, and closing are common morphological operations. Mathematically, these operations are defined using structuring elements (kernels) and applied to binary images to modify object boundaries and remove noise. For instance, erosion E and dilation D can be expressed as:

$$\begin{aligned} E(A) = \bigcap _{i=1}^{n} (A - B_i) \end{aligned}$$(12)$$\begin{aligned} D(A) = \bigcup _{i=1}^{n} (A \oplus B_i) \end{aligned}$$(13)Where A\(\rightarrow\) input binary image, \(B_i\)\(\rightarrow\) structuring element, and \(\oplus\) and − denotes dilation and erosion operations, respectively.

Dataset division

The dataset from Kaggle is divided into two sets: 70% for training and 30% for testing. The training set is utilized to train the classifier, allowing it to learn patterns and features indicative of PCOS, while the testing set evaluates the performance of the model and ensures its ability to generalize and accurately diagnose PCOS on unseen data.

Feature extraction

The process of feature extraction transforms raw data into a set of informative attributes which reduces the complexity of the data by focusing on the most relevant aspects, enhancing the performance and efficiency of models. InceptionNet V3 and Convolutional Autoencoder have been used for feature extraction in our approach. These methods integrate to form a comprehensive model named CystNet, which combines the strengths of both techniques to complete the feature extraction process, represented in Fig. 5. Each method is described in detail below:

Feature extraction using InceptionNetV3

Unlike traditional CNN models that use specific receptive field sizes in different layers for feature extraction, the Inception module employs kernels of various sizes (1\(\times\)1, 3\(\times\)3, and 5\(\times\)5) in parallel41. These parallel features are then depth-wise stacked to produce the output of the module. Additionally, a 3\(\times\)3 max-pooled version of the input is included in the feature stack. This combined output delivers rich, multi-perspective feature maps to the subsequent convolutional layer, contributing to the effectiveness of the Inception module in applications such as medical imaging, in our case with PCOS ultrasound images.

InceptionNet V342, a variant of the Inception architecture, has been employed in this study for feature extraction. Retaining three Inception modules and one grid size reduction block, followed by Max Pooling and Global Average Pooling layers to decrease the output dimensions. It is a 48-layer deep convolutional neural network capable of recognizing intricate patterns and features in medical images and employs convolution kernel splitting to break down large convolutions into smaller ones, such as dividing a 3\(\times\)3 convolution into 3\(\times\)1 and 1\(\times\)3convolutions, developed by Keras and pre-trained on ImageNet. After convolution, the channels are aggregated and non-linear fusion is performed, enhancing the adaptability of the network to different scales, preventing overfitting, and enhancing spatial feature extraction. With input matrix \(A_X\) given in equation 23, the convolutional operation followed by ReLU activation, max-pooling, and global average pooling is represented as follows:

In these equations, \(W^i\)\(\rightarrow\) weight tensor of the \(i^{th}\)convolutional layer, \(X^i\)\(\rightarrow\) output feature map after the \(i^{th}\) layer, \(b^{(i)}\)\(\rightarrow\) bias vector, and \(X_{\text {features}}\)\(\rightarrow\) final feature vector obtained after applying global average pooling, while M and N represent the height and width of the spatial dimensions of the feature map X, respectively.

Feature extraction using convolutional autoencoder

An autoencoder can utilize various types of neurons, but convolutional kernels are particularly effective for 2D data, making them ideal for handling images. Convolutional autoencoders share a structural similarity with CNNs, including convolution filters and pooling layers44. Another benefit of CNNs is their ability to maintain and utilize the spatial information inherently present in images43. Moreover, the convolutional autoencoder converts 2D data representations into 1D arrays. For example, it transforms the positions of m pins, given as pairs of coordinates (p, q) in \(\mathbb {R}^{m \times 2}\), into a 1D format and ensures that the input and output nodes have the same dimensionality, allowing for a direct comparison between the input and output images43. This comparison is utilized as an objective function to learn the parameters of the autoencoder. Since the learning process is label-independent, convolutional autoencoders are considered unsupervised methods. Equation 22 is used to express the latent encoding of the \(i^{th}\) feature map in the encoder for a single-channel input p.

where \(*\) represents 2D convolution, \(w_i\)\(\rightarrow\)convolutional filters in the encoder, and \(\sigma\)\(\rightarrow\) activation function. The decoder reconstructs the image using:

where b\(\rightarrow\) bias per input channel, L\(\rightarrow\) set of latent feature maps, and \(\bar{w}\)\(\rightarrow\) learnable de-convolution filters. The objective function minimized during training is the mean squared error (MSE), defined as:

where \(\theta\)\(\rightarrow\) parameters of the autoencoder, \(p_k\)\(\rightarrow\) the input image in the dataset, and \(q_k\)\(\rightarrow\) the reconstructed image produced by the autoencoder.

Image classification

After feature extraction, we have applied two approaches for image classification: Classification Using Dense Layer and Classification Using ML Classifiers are explained below:

Classification using dense layer

In the Dense Layer classification, a fully connected neural network is used to perform the final classification of the extracted features. The network architecture typically consists of multiple dense layers, each followed by activation functions and dropout layers to prevent overfitting. The operations or blocks are described below:

Input Layer: The input to the dense network is a feature vector x extracted from the previous stages. If the feature vector has n features, it is represented as:

Dense Layers: Each dense layer performs a linear transformation followed by a non-linear activation function. For a given layer l, the transformation can be expressed as:

where \(a^{(l-1)}\)\(\rightarrow\) activation from the previous layer, \(W^l\)\(\rightarrow\) weight matrix of layer l, and \(b^l\)\(\rightarrow\) bias vector of layer l. The activation function applied to the linear transformation is typically a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU), defined as:

Dropout Layers: Dropout layers are used during training to prevent overfitting by randomly setting a fraction p of the input units to zero. Mathematically, this can be expressed as:

where \(d^l\)\(\rightarrow\) binary mask vector sampled from a Bernoulli distribution with parameter p.

Output Layer: The final layer is a dense layer or fully connected layer with a sigmoid activation function that outputs the probability of the positive class for binary classification:

where \(W^{\text {out}}\) and \(b^{\text {out}}\) are the weights and biases of the output layer, \(a^L\)\(\rightarrow\) activation from the last hidden layer, and \(\sigma\)\(\rightarrow\) sigmoid function, which is calculated as:

Model Compilation: During the training process, the model parameters are optimized using the Adam optimizer, which dynamically adjusts the learning rate for efficient convergence. The optimization aims to minimize the loss function, specified as the binary cross-entropy, which quantifies the difference between predicted and actual labels. Additionally, the training incorporates rigorous 5-fold cross-validation to ensure robustness and generalization to unseen data. In 5-fold cross-validation, the dataset is divided into five subsets, and the model is trained on four subsets while the remaining one is held out for validation as depicted in Fig. 6. This process iterates five times, with each subset used once as the validation data. Mathematically, the loss function can be expressed as:

where n\(\rightarrow\) number of samples, \(o_i\)\(\rightarrow\) true label of the \(i^{th}\) sample, and \(P_i\)\(\rightarrow\) predicted probability of the positive class. Additionally, the k-fold cross-validation process is mathematically represented as:

where K\(\rightarrow\) number of folds, and \(E_k\)\(\rightarrow\) performance metric obtained on the \(k^{th}\) fold during validation.

Classification using ML algorithms

In addition to the deep learning approach, traditional machine learning classifiers are also employed for the classification of PCOS. These classifiers include Naïve Bayes (NB), k-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN), Random Forest (RF), and Adaptive Boosting (ADB) where the features extracted by the CystNet model serve as the input for these classifiers. Each of the classifiers is briefly discussed below:

-

1.

K-Nearest Neighbor: The K-NN57 classifier is a straightforward, instance-based learning algorithm used for classification tasks. It classifies a new instance by identifying the K closest training instances (neighbors) using a distance metric, commonly the Euclidean distance. The Euclidean distance between two instances \(x_i\) and \(x_j\) with m features is given by:

$$\begin{aligned} d(x_i, x_j) = \sqrt{\sum _{l=1}^m (x_{il} - x_{jl})^2} \end{aligned}$$(33)The class label of the \(i^{th}\) neighbor \(\hat{y}\) is then determined by the majority vote of its K-nearest neighbors:

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{y} = \text {mode}\{y_i | i = 1, 2, \ldots , K\} \end{aligned}$$(34) -

2.

Naïve Bayes: Naïve Bayes57 is a probabilistic classifier grounded on Bayes’ theorem, operating with an assumption of feature independence. Given a feature vector \(x = (x_1, x_2, \ldots , x_n)\) and a class \(C_k\), the classifier computes the class with the highest posterior probability using the formula:

$$\begin{aligned} P(M_k | x) = \frac{P(x | M_k) \cdot P(M_k)}{P(x)} \end{aligned}$$(35)This calculation involves the likelihood \(P(x | M_k)\), the prior probability \(P(M_k)\), and the marginal likelihood P(x).

-

3.

Random Forest: An RF57 classifier is an ensemble learning method used for classification tasks, where it constructs multiple decision trees and outputs the class that is the mode of the classes predicted by the individual trees. Mathematically, for a new instance x, the prediction \(\hat{y}\) is the mode of the predictions from B trees:

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{y} = \text {mode}\{h_b(x) | b = 1, 2, \ldots , B\} \end{aligned}$$(36)where \(h_b(x)\) is the prediction of the \(b^{th}\) tree. The best split \(s^*\) at each node is found by minimizing the impurity, such as the Gini impurity:

$$\begin{aligned} s^* = \arg \min _s \sum _{k \in \{L, R\}} \frac{|D_k|}{|D|} \cdot \text {Gini}(D_k) \end{aligned}$$(37)where \(D_L\) and \(D_R\) are the left and right splits of the node, respectively.

-

4.

Adaptive Boosting: ADB58 classifier combines multiple weak models to create a strong classifier. It iteratively trains models, giving more weight to misclassified samples. The final strong classifier H(x) is a weighted sum of the individual weak classifiers \(h_t(x)\):

$$\begin{aligned} H(x) = \text {sign}\left( \sum _{t=1}^T \alpha _t h_t(x) \right) \end{aligned}$$(38)where t is the index of the individual weak classifiers, and T is the total number of weak classifiers.

Experimental results

Performance evaluation metrics

To assess the performance of the model, various performance metrics have been utilized efficiently. These metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s effectiveness in accurately classifying the ultrasound images and diagnosing PCOS. The foundation for these metrics is the confusion matrix (CM)59, which captures the model’s predictions against the actual classifications. The following terms of the confusion matrix are discussed below :

-

True Positive (\(\textit{TP}_{os}\)): This occurs when the classifier correctly identifies a patient as having PCOS.

-

True Negative (\(\textit{TN}_{eg}\)): This occurs when the classifier correctly identifies a patient as not having PCOS.

-

False Positive (\(\textit{FP}_{os}\)): This occurs when the classifier incorrectly identifies a patient as having PCOS when they do not.

-

False Negative (\(\textit{FN}_{eg}\)): This occurs when the classifier incorrectly identifies a patient as not having PCOS when they actually do.

Based on this matrix, several metrics have been calculated and are briefly discussed below:

-

1.

Accuracy: The ratio of correctly predicted instances to the total instances59. Mathematically,

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Accuracy} = \frac{TP_{os} + TN_{eg}}{TP_{os} + TN_{eg} + FP_{os} + FN_{eg}} \end{aligned}$$(39) -

2.

Precision: It indicates the accuracy of the positive predictions made by the model59. Mathematically,

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Precision} (P_e) = \frac{TP_{os}}{TP_{os} + FP_{os}} \end{aligned}$$(40) -

3.

Recall: It measures the ability of the model to identify all relevant instances in the dataset59. Mathematically,

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Recall} (R_e) = \frac{TP_{os}}{TP_{os} + FN_{eg}} \end{aligned}$$(41) -

4.

F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall59. Mathematically,

$$\begin{aligned} \text {F1 score} = \frac{2 \times P_e \times R_e}{P_e + R_e} \end{aligned}$$(42) -

5.

Specificity: It measures the ability of the model to correctly identify negative instances59. Mathematically,

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Specificity} (s_e) = \frac{TN_{eg}}{TN_{eg} + FP_{os}} \end{aligned}$$(43) -

6.

ROC-AUC: The ROC-AUC curve represents the ability of the model to distinguish between classes59.

Each metric offers a unique perspective on the performance of the model, capturing different aspects of the classification task. Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1 Score, Specificity, and ROC-AUC were chosen because they collectively measure the model’s ability to correctly identify both positive and negative instances, the trade-off between precision and recall, and the overall discriminative power of the model.

Result and discussion

The proposed framework for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) detection is implemented using an 8th-generation Intel Core i7 processor, 8 GB RAM, and Python programming tools. The results demonstrate the efficacy of the system in accurately diagnosing PCOS from ultrasound images, with substantial improvements over traditional methods. The necessity for precise PCOS diagnosis lies in its significant impact on women’s reproductive health, affecting approximately 15% of reproductive-aged women globally. Early detection is vital to manage associated symptoms such as acne, alopecia, hirsutism, and infertility, thereby enhancing the quality of life and reducing long-term health risks. Our study introduces an advanced automated system that utilizes AI techniques, including Machine Learning, Transfer Learning, and Deep Learning, to detect and classify PCOS from ultrasound images. The image pre-processing techniques, such as image resizing, normalization, augmentation, division, and segmentation which contribute significantly to the accurate identification of follicles and cysts, reducing the likelihood of manual errors. Furthermore, the proposed CystNet hybrid model for feature extraction integrates InceptionNet V3 and Convolutional Autoencoder approaches, effectively highlighting critical features from the ultrasound images and perceiving subtle differences between affected and unaffected cases. This model extracts 2048 features from InceptionNet V3 and 1024 features from a convolutional autoencoder, which are then rescaled and concatenated, resulting in a total of 3062 features for the subsequent classification stage. The classification phase of the system is diverged into two approaches: Approach A and Approach B.

In Approach A, the system employs a dense (fully connected) layer for classification, as detailed in Table 2. CystNet achieved an accuracy of 96.54%, a precision of 94.21%, a recall of 97.44%, a F1-score of 95.75%, and a specificity of 95.92% on the Kaggle PCOS US images. These metrics indicate a high level of diagnostic precision and reliability, outperforming other deep learning models like InceptionNet V3, Autoencoder, ResNet50, DenseNet121, and EfficientNetB0. The accuracy and loss graphs in Fig. 7 further illustrate the robust training and validation process for Approach A, with minimal overfitting observed. Moreover, the effectiveness of Approach A extends to other datasets, as reflected in its better performance on additional datasets. Specifically, Approach A achieved an accuracy of 94.39% when applied to the PCOSGen dataset, and this approach further demonstrated the robustness with an accuracy of 95.67% on the MMOTU dataset. These results represent the versatility and reliability of Approach A across different data sources.

Approach B integrates machine learning classifiers for the final classification phase after feature extraction with CystNet. The Random Forest classifier led the performance, achieving an accuracy of 97.75%, a precision of 96.23%, a recall of 98.29%, a F1-score of 97.19%, and a specificity of 97.37% on the Kaggle PCOS US images, as represented in Table 3. This approach outperforms traditional methods and other classifiers such as Adaptive Boosting, K-Nearest Neighbors, and Naive Bayes. Figures 8 and 9 depict the confusion matrix and AUC curves, respectively, further validating the high diagnostic accuracy of both approaches and highlighting the high diagnostic precision and reliability of the suggested model. Furthermore, Approach B exhibited better performance across various datasets, demonstrating its capability to generalize effectively. On the PCOSGen dataset, this approach attained an accuracy of 96.12%, while on the MMOTU dataset, it excelled further, reaching an accuracy of 97.23%. The outcomes represent the ability of Approach B to maintain high diagnostic accuracy and reliability across different medical datasets.

A brief comparison with previous studies indicates that our approach surpasses existing methods in terms of accuracy and reliability, emphasizing its potential for medical application. The recent systematic review by Arora et al.64 highlights various machine learning algorithms for PCOS diagnosis, observing the challenges and limitations of current techniques in capturing the complexity of the syndrome. Paramasivam et al.62 developed a Self-Defined CNN (SD_CNN) for PCOS classification, achieving a notable accuracy of 96.43% using a Random Forest Classifier. While their model is effective, our approach incorporates a more comprehensive feature extraction process, leading to higher accuracy and robustness. A CNN-based automation for PCOS diagnosis with a focus on model interpretability using the Grad-CAM technique was presented by Galagan et al.65. Moreover, Kermanshahchi et al.66 introduced a machine learning-based model for PCOS detection on a specialized dataset. While their approach emphasizes transparency in decision-making, the integration of multiple AI techniques in our proposed approach enhances its generalizability across diverse datasets, making it more suitable for real-world clinical settings. Table 4 demonstrates that our approach surpasses existing methods in terms of accuracy and reliability, further emphasizing its potential for medical application. Additionally, the performance consistency across different divisions of training and test sets in Table 5 and various folds for cross-validation in Table 6 highlight the robustness of our system.

The sophistication of the proposed solution primarily arises from the integration of multiple AI techniques, including ML, TL, and DL. The CystNet hybrid model, which combines InceptionNet V3 with a Convolutional Autoencoder, involves extensive computation for feature extraction and integration. Unlike existing approaches, which often rely on single-stage or less integrated approaches, our method’s novelty lies in its comprehensive feature extraction and hybrid model integration, which enhances feature representation and classification performance. Despite the advancements, the current solution has limitations. One major limitation is that the dataset used for training and evaluation originates from a single source, which may not fully represent the variability found in diverse populations. This could affect the generalizability and performance of the model in real-world clinical settings. Additionally, the computational demands of the CystNet model may limit its practical deployment on devices with lower processing power. Future research should incorporate multi-source datasets to enhance model robustness. Additionally, real-time deployment and integration into clinical workflows pose challenges, necessitating further development in terms of computational efficiency and user-friendly interfaces for healthcare professionals. However, the experimental results underscore the potential of the proposed framework in revolutionizing PCOS diagnosis through automated image analysis and classification techniques. By streamlining the diagnostic process and improving accuracy, the framework holds promise in facilitating timely interventions and reducing the burden on healthcare professionals, ultimately benefiting women’s reproductive health and well-being.

Conclusion and future work

Diagnosing Polycystic Ovary Syndrome is crucial due to its significant impact on the reproductive health of women, affecting approximately 15% of reproductive-aged women globally. In this study, a dataset obtained from Kaggle, consisting of ultrasound images labeled as ’INFECTED’ (cystic ovaries) and ’NOT INFECTED’ (healthy ovaries), is used. These images are augmented using various transformations, such as rotation, flipping, zooming, and shifting, and segmented using techniques like the Watershed technique, multilevel thresholding, and morphological processing to ensure precise image segmentation. An advanced automated system is developed using AI techniques, including ML, TL, and DL, to detect and classify PCOS, with the proposed CystNet hybrid model integrating InceptionNet V3 and Convolutional Autoencoder to effectively extract critical features from the ultrasound images. During the classification phase, both a dense layer and traditional ML classifiers are employed to enhance the robustness of the classification process. With a 5-fold cross-validation process, the dense layer approach achieved an accuracy of 96.54%, precision of 94.21%, recall of 97.44%, and specificity of 95.92%, while the RF classifier achieved an impressive accuracy of 97.75%, precision of 96.23%, recall of 98.29%, and specificity of 97.19%. The results highlight the potential of the proposed framework to streamline the diagnostic process, reducing manual errors and time consumption while facilitating timely interventions for women’s reproductive health. Future work could focus on incorporating multi-source datasets from diverse populations to improve the model’s generalizability. Moreover, enhancing computational efficiency and developing user-friendly interfaces are crucial steps to ensure the practical usability of the system.

Data availability and access

The PCOS ultrasound dataset is available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/anaghachoudhari/pcos-detection-using-ultrasound-images.

References

Khan, I. U. et al. Deep learning-based computer-aided classification of amniotic fluid using ultrasound images from Saudi Arabia. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 6, 107 (2022).

Gopalakrishnan, C. & Iyapparaja, M. Active contour with modified otsu method for automatic detection of polycystic ovary syndrome from ultrasound image of ovary. Multimed. Tools Appl. 79, 17169–17192 (2020).

Stein, I. F. & Leventhal, M. L. Amenorrhea associated with bilateral polycystic ovaries. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 29, 181–191 (1935).

Organization, W. H. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines Vol. 1 (World Health Organization, London, 1992).

Azziz, R. et al. The androgen excess and pcos society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: The complete task force report. Fertil. Steril. 91, 456–488 (2009).

Laven, J. S., Imani, B., Eijkemans, M. J. & Fauser, B. C. New approach to polycystic ovary syndrome and other forms of anovulatory infertility. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 57, 755–767 (2002).

Dewailly, D. et al. Definition and significance of polycystic ovarian morphology: A task force report from the androgen excess and polycystic ovary syndrome society. Hum. Reprod. Update 20, 334–352 (2014).

Nandipati, S. C. & Ying, C. X. Polycystic ovarian syndrome (pcos) classification and feature selection by machine learning techniques. Appl. Math. Comput. Intell. 9, 65–74 (2020).

Morgante, G., Cappelli, V., Di Sabatino, A., Massaro, M. & De Leo, V. Polycystic ovary syndrome (pcos) and hyperandrogenism: The role of a new natural association. Minerva Ginecol. 67, 457–463 (2015).

Ganie, M. A. et al. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, genetics & management of polycystic ovary syndrome in India. Indian J. Med. Res. 150, 333–344 (2019).

Bharathi, R. V. et al. An epidemiological survey: Effect of predisposing factors for pcos in Indian urban and rural population. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 22, 313–316 (2017).

Ramamoorthy, S., Senthil Kumar, T., Md. Mansoorroomi, S. & Premnath, B. Enhancing intricate details of ultrasound pcod scan images using tailored anisotropic diffusion filter (tadf). In Intelligence in Big Data Technologies—Beyond the Hype: Proceedings of ICBDCC 2019, 43–52 (Springer, 2021).

Palomba, S., Piltonen, T. T. & Giudice, L. C. Endometrial function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A comprehensive review. Hum. Reprod. Update 27, 584–618 (2021).

Kałużna, M. et al. Effect of central obesity and hyperandrogenism on selected inflammatory markers in patients with pcos: A whtr-matched case-control study. J. Clin. Med. 9, 3024 (2020).

Kahsar-Miller, M. D., Nixon, C., Boots, L. R., Go, R. C. & Azziz, R. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome (pcos) in first-degree relatives of patients with pcos. Fertil. Steril. 75, 53–58 (2001).

Holste, G. et al. End-to-end learning of fused image and non-image features for improved breast cancer classification from mri. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 3294–3303 (IEEE, 2021).

Gopalakrishnan, C. & Iyapparaja, M. A detailed research on detection of polycystic ovary syndrome from ultrasound images of ovaries. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 8, S11 (2019).

Wang, R. & Mol, B. W. J. The Rotterdam criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: Evidence-based criteria?. Hum. Reprod. 32, 261–264 (2017).

Rachana, B. et al. Detection of polycystic ovarian syndrome using follicle recognition technique. Global Trans. Proc. 2, 304–308 (2021).

Balen, A. H., Laven, J. S., Tan, S.-L. & Dewailly, D. Ultrasound assessment of the polycystic ovary: International consensus definitions. Hum. Reprod. Update 9, 505–514 (2003).

Sitheswaran, R. & Malarkhodi, S. An effective automated system in follicle identification for polycystic ovary syndrome using ultrasound images. In 2014 international conference on electronics and communication systems (ICECS), 1pp. –5 (IEEE, 2014).

Deng, Y., Wang, Y. & Chen, P. Automated detection of polycystic ovary syndrome from ultrasound images. In 2008 30th annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society, pp. 4772–4775 (IEEE, 2008).

Liu, S. et al. Deep learning in medical ultrasound analysis: A review. Engineering 5, 261–275 (2019).

Khan, I. U. et al. Amniotic fluid classification and artificial intelligence: Challenges and opportunities. Sensors 22, 4570 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Robust mobile crowd sensing: When deep learning meets edge computing. IEEE Network 32, 54–60 (2018).

Yadav, N., Dass, R. & Virmani, J. A systematic review of machine learning based thyroid tumor characterisation using ultrasonographic images. J. Ultrasound 27, 209–224 (2024).

Yadav, N., Dass, R. & Virmani, J. Despeckling filters applied to thyroid ultrasound images: A comparative analysis. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81, 8905–8937 (2022).

Yadav, N., Dass, R. & Virmani, J. Deep learning-based cad system design for thyroid tumor characterization using ultrasound images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 43071–43113 (2024).

Dass, R. & Yadav, N. Image quality assessment parameters for despeckling filters. Proc. Comput. Sci. 167, 2382–2392 (2020).

Virmani, J. et al. Assessment of despeckle filtering algorithms for segmentation of breast tumours from ultrasound images. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 39, 100–121 (2019).

Haider, I., Tran, M.-T., Kim, S.-H., Yang, H.-J. & Lee, G.-S. An ensemble approach for multiple emotion descriptors estimation using multi-task learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.10878 (2022).

Aziz, S., Munir, K., Raza, A., Almutairi, M. S. & Nawaz, S. Ivnet: Transfer learning based diagnosis of breast cancer grading using histopathological images of infected cells. IEEE Access 11, 127880–127894 (2023).

Kriti, V. J. & Agarwal, R. Deep feature extraction and classification of breast ultrasound images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 79, 27257–27292 (2020).

Maggipinto, M., Masiero, C., Beghi, A. & Susto, G. A. A convolutional autoencoder approach for feature extraction in virtual metrology. Proc. Manuf. 17, 126–133 (2018).

Gayathri, S., Gopi, V. P. & Palanisamy, P. Diabetic retinopathy classification based on multipath cnn and machine learning classifiers. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 44, 639–653 (2021).

Gopalakrishnan, C. & Iyapparaja, M. Multilevel thresholding based follicle detection and classification of polycystic ovary syndrome from the ultrasound images using machine learning. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag.[SPACE] https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-021-01203-x (2021).

Alamoudi, A. et al. A deep learning fusion approach to diagnosis the polycystic ovary syndrome (pcos). Appl. Comput. Intell. Soft Comput. 2023, 9686697 (2023).

Nilofer, N. et al. Follicles classification to detect polycystic ovary syndrome using glcm and novel hybrid machine learning. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 12, 1062–1073 (2021).

Suha, S. A. & Islam, M. N. An extended machine learning technique for polycystic ovary syndrome detection using ovary ultrasound image. Sci. Rep. 12, 17123 (2022).

Maheswari, K., Baranidharan, T., Karthik, S. & Sumathi, T. Modelling of f3i based feature selection approach for pcos classification and prediction. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 12, 1349–1362 (2021).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp 2818–2826 (IEEE, 2016).

Pan, Y. et al. Fundus image classification using inception v3 and resnet-50 for the early diagnostics of fundus diseases. Front. Physiol. 14, 1126780 (2023).

Polic, M., Krajacic, I., Lepora, N. & Orsag, M. Convolutional autoencoder for feature extraction in tactile sensing. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 4, 3671–3678 (2019).

Lee, H., Kim, J., Kim, B. & Kim, S. Convolutional autoencoder based feature extraction in radar data analysis. In 2018 Joint 10th international conference on soft computing and intelligent systems (SCIS) and 19th international symposium on advanced intelligent systems (ISIS), pp. 81–84 (IEEE, 2018).

Patil, S. D., Deore, P. J. & Patil, V. B. An intelligent computer aided diagnosis system for classification of ovarian masses using machine learning approach. Int. Res. J. Multidiscip. Technovation 6, 45–57 (2024).

Rahman, W. et al. Multiclass blood cancer classification using deep cnn with optimized features. Array 18, 100292 (2023).

Jung, Y. et al. Ovarian tumor diagnosis using deep convolutional neural networks and a denoising convolutional autoencoder. Sci. Rep. 12, 17024 (2022).

Bhosale, S., Joshi, L. & Shivsharanan, A. Pcos (polycystic ovarian syndrome) detection using deep learning. Int. Res. J. Modern. Eng. Technol. Sci.[SPACE] https://doi.org/10.1109/IC3I59117.2023.10397615 (2022).

Khamparia, A. et al. Diagnosis of breast cancer based on modern mammography using hybrid transfer learning. Multidimens. Syst. Signal Process. 32, 747–765 (2021).

Dewi, R., Adiwijaya, W. U. N. & Jondri,. Classification of polycystic ovary based on ultrasound images using competitive neural network. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 971, 012005 (2018).

Chen, M., Shi, X., Zhang, Y., Wu, D. & Guizani, M. Deep feature learning for medical image analysis with convolutional autoencoder neural network. IEEE Trans. Big Data 7, 750–758 (2017).

Choudhari, A. Pcos detection using ultrasound images. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/anaghachoudhari/pcos-detection-using-ultrasound-images (2024). [Online].

Handa, P. et al. Pcosgen-train dataset. https://zenodo.org/records/10430727 (2023). [Online].

Zhao, Q. et al. A multi-modality ovarian tumor ultrasound image dataset for unsupervised cross-domain semantic segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.06799 (2022).

Zhao, Z., Kleinhans, A., Sandhu, G., Patel, I. & Unnikrishnan, K. Capsule networks with max-min normalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.09662 (2019).

Perez, L. & Wang, J. The effectiveness of data augmentation in image classification using deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.04621 (2017).

Lanjewar, M. G., Panchbhai, K. G. & Charanarur, P. Lung cancer detection from ct scans using modified densenet with feature selection methods and ml classifiers. Expert Syst. Appl. 224, 119961 (2023).

Taherkhani, A., Cosma, G. & McGinnity, T. M. Adaboost-cnn: An adaptive boosting algorithm for convolutional neural networks to classify multi-class imbalanced datasets using transfer learning. Neurocomputing 404, 351–366 (2020).

Japkowicz, N. & Shah, M. Performance evaluation in machine learning. Mach. Learn. Radiat. Oncol. Theory Appl. 41–56 (2015).

Nakhua, H., Ramachandran, P., Surve, A., Katre, N. & Correia, S. An ensemble approach for ultrasound-based polycystic ovary syndrome (pcos) classification. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 30, 14589–14597 (2024).

Bedi, P., Goyal, S., Rajawat, A. S. & Kumar, M. An integrated adaptive bilateral filter-based framework and attention residual u-net for detecting polycystic ovary syndrome. Decis. Anal. J. 10, 100366 (2024).

Paramasivam, G. B. & Ramasamy Rajammal, R. Modelling a self-defined cnn for effectual classification of pcos from ultrasound images. Technol. Health Care 1–17.

Chitra, P. et al. Classification of ultrasound pcos image using deep learning based hybrid models. In 2023 second international conference on electronics and renewable systems (ICEARS), 1389–1394 (IEEE, 2023).

Arora, S., Vedpal & Chauhan, N. Polycystic ovary syndrome (pcos) diagnostic methods in machine learning: a systematic literature review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 1–37 (2024).

Galagan, R., Andreiev, S., Stelmakh, N., Rafalska, Y. & Momot, A. Automation of polycystic ovary syndrome diagnostics through machine learning algorithms in ultrasound imaging. Appl. Comput. Sci. 20, 194–204 (2024).

Kermanshahchi, J., Reddy, A. J., Xu, J., Mehrok, G. K. & Nausheen, F. Development of a machine learning-based model for accurate detection and classification of polycystic ovary syndrome on pelvic ultrasound. Cureus 16 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research work is part of the project supported by DST under the PURSE 2022 scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have substantial contributions to prepare the article. All of them provided critical feedback and helped to shape the research work. Poonam Moral has designed the model, performed the experiment, analyzed the data. She has thoroughly investigated the data set used in this research work. She also took a lead in conceptualization of the idea and writing the original draft. She is also acting as a corresponding author. Debjani Mustafi contributed to design and implementation of the research, conceptualization of the proposed method, framing and drafting the manuscript. She provided the overall planning of the research work and conceived the original idea along with reviewing the paper. Abhijit Mustafi aided in interpreting the results and analysis and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. He has contributed in the conceptualization of the proposed method. The author has also reviewed the entire paper. Sudip Kumar Sahana has given a critical review of the research paper. He took active part for collection, analysis of datasets.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare that are relevant to the contents of the manuscripts.

Ethical and informed consent for data used

The datasets employed in this study were obtained from publicly available sources, and their utilization adheres to ethical standards and guidelines. As these datasets are publicly accessible, specific informed consent was not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moral, P., Mustafi, D., Mustafi, A. et al. CystNet: An AI driven model for PCOS detection using multilevel thresholding of ultrasound images. Sci Rep 14, 25012 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75964-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75964-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Feature fusion context attention gate UNet for detection of polycystic ovary syndrome

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Automated high precision PCOS detection through a segment anything model on super resolution ultrasound ovary images

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Nanomaterial-enhanced biosensors for polycystic ovarian syndrome diagnosis and pathophysiological insights

Microchimica Acta (2025)

-

Artificial intelligence in polycystic ovarian syndrome management: past, present, and future

La radiologia medica (2025)

-

Advancement in early diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome: biomarker-driven innovative diagnostic sensor

Microchimica Acta (2025)