Abstract

Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial to prevent disease development and define therapeutic strategies. Due to predominantly unspecific symptoms, diagnosis of autoimmune diseases (AID) is notoriously challenging. Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) are a promising method with the potential to enhance and expedite precise diagnostics by physicians. However, due to the difficulties of integrating and encoding multi-omics data with clinical values, as well as a lack of standardization, such systems are often limited to certain data types. Accordingly, even sophisticated data models fall short when making accurate disease diagnoses and presenting data analyses in a user-friendly form. Therefore, the integration of various data types is not only an opportunity but also a competitive advantage for research and industry. We have developed an integration pipeline to enable the use of machine learning for patient classification based on multi-omics data in combination with clinical values and laboratory results. The application of our framework resulted in up to 96% prediction accuracy of autoimmune diseases with machine learning models. Our results deliver insights into autoimmune disease research and have the potential to be adapted for applications across disease conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autoimmune diseases (AIDs) affect approximately 7% of the population1,2. The past two decades have witnessed an increasing incidence of AIDs2,3,4 resulting in an annual cost of $14 billion to healthcare systems3,5. This diverse group of diseases is among the most challenging to diagnose and they often remain undiagnosed until progression to an advanced stage. As a result, the disease remains untreated for a long time and can progress continuously, while patients face high-impact health consequences6. AIDs are conventionally classified based on the involved organ or system7, leading to over 100 clinically distinct disorders. Historically, AIDs have been treated as distinct entities, partly due to their management by specialized medical disciplines. However, the emergence of comprehensive omics data has facilitated a more precise understanding of AIDs. Molecular genomic, immunomic and metabolomic profiles have the potential to serve as early biomarkers for diagnosis and enable prompt therapeutical intervention8,9,10,11,12. However, the integration and interoperation of omics data are obstacles to the transition to personalized medicine. The bottleneck in omics techniques is not due to data generation, but rather to constraints in data management, integration, analysis, visualization and interpretation. These limitations have caused a substantial delay in the progress of omics over the past decade. An additional challenge is the identification of meaningful and interpretable relationships within integrated omics data13. Analytical pipelines for each type of omics data are already available, and multi-omics approaches are being developed for a wide range of biological problems14. However, combining clinical, laboratory, and omics data without standard analytical procedures can affect data interpretation. Additionally, integrated and encoded data are needed as input to artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML) methods that detect diagnostically and therapeutically relevant patterns in large datasets15.

Clinical data sets can support precision diagnostics as well. Electronic health records (EHR) contain clinical data subject to multiple regulations and rules to safeguard patient privacy and prevent misuse. On the other hand, observational data sets, while offering the advantage of large scale and generalizability of their findings, come with their own set of constraints that must be addressed before adequate analysis is possible. These constraints include potential inaccuracies or inconsistencies due to errors or missing data, their dynamic nature resulting from being captured or not over time, and the potential for bias due to non-random selection of tests and treatments. Despite these challenges, both clinical data from EHRs and observational data have the potential to offer significant benefits for medical research due to their low cost and large scale16,17.

Alongside clinical records, laboratory data is routinely generated by examination of blood, urine and other biological samples. Laboratory tests may be required for the diagnosis, the development of a treatment strategy, and monitoring. Cytokine levels, commonly measured through hematological analysis evaluation represent some of the most frequently reported laboratory tests18.

Over 200 genetic loci have been associated with autoimmune disorders. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) technology sequences an organism’s entire DNA, while whole-exome sequence (WES) targets only the 1–2% of the human genome containing protein-coding genes. Although smaller, the exome is critical for identifying genetic variations underlying genetic disorders. Exome sequencing is a cost-effective and time-efficient alternative to WGS that can identify disease-contributing genetic variations with fewer resources and less time19,20. This sequencing method has been used to identify rare or novel deleterious variants as the genetic causes of disease and can lead to identification of personalized treatments21,22. Despite the demonstrated utility of integrated omics data, WES data have been underutilized in qualitatively responsive diagnostic procedures in conjunction with other omics, clinical, and laboratory data23.

In addition, B-cell repertoire high-throughput sequencing has revealed good evidence for a pathological role of B-cells in three polygenic AIDs: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)8,24. However, immunomics data alone has limited utility in the differential diagnosis of autoimmune disorders25. Single-cell-level description of immune repertoires, such as V, D, and J germlines and CDR3 clonal diversity, identify health and disease-related patterns24,26,27.

Metabolomics has shown potential to diagnose AIDs28. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) has evolved into an effective technique for concurrently identifying numerous metabolites, including amino acids, lipids, and carbohydrates29, providing essential data about potential metabolic abnormalities.

Clinical, laboratory and multi-omics have potential in precision of diagnostics in AIDs, however, integration of multiple and high-dimensional data remains a challenge. Several integration procedures have been proposed, each with benefits and limitations30,31,32. These datasets are transformed to minimize their complexity and variability with approaches of feature selection and feature extraction33. To apply ML for improved AID diagnostics, categorical data needs to be encoded into numerical representations A suitable encoding method of omics data that include biological sequences is one-hot encoding: a validated approach that converts inputs into binary form34,35,36. However, there is no standard approach for encoding genomic sequencing data for in silico diagnosis of genetic diseases. Previous encoding methods annotated gene mutations using predictors of genomic variant effects or by encoding each genetic variant of each chromosome, that result in a large number of feature vectors, thus increasing data model complexity. To address this issue, we provide an encoding strategy to capture the accumulation of genetic variants per chromosome as well as of antibody sequences37. Heterogeneity, data sparsity, and the feature-to-sample ratio make it challenging to apply machine learning to multi-omics data. In addition, imbalanced classes in disease classification increase the risk of overfitting. To address these challenges, we applied dimensionality reduction techniques for feature selection and extraction within each data type38, generated digital patients and applied oversampling to balance data classes, thus enabling data transformation for integration and the application of ML reducing biases. We propose standardized preprocessing, comprehensive feature selection and encoding methods to mitigate issues in multi-omics data integration. We show their effect on ML prediction accuracy and potential biomarker discovery for precision diagnostics.

Results

Clinical, laboratory, and multi-omics data integration pipeline

It has been demonstrated that the combination of molecular with non-omics data has shown to provide a more accurate diagnosis than utilizing either type of information separately39. We developed a versatile pipeline to preprocess raw data and integrate different health data types to enable ML models classify and support the diagnosis of AIDs (Fig. 1). The integration of multiple data types in organized, coherent, and comprehensive data structures enabled the application of a wide range of analytical techniques. An integrated analysis of clinical, laboratory, and omics characteristics of patients enhanced the confidence in predicting AIDs. Additionally, the structure of our pipeline enables the application of ML to an ever-increasing range of omics data. The methods developed and the proposed pipeline contribute to consolidate multi-omics data integration in the biomedical field and establish its applicability in terms of validation and standardization.

Health data integration and machine learning workflow for personalized diagnostics of autoimmune diseases. (A) Clinical, laboratory and omics data were collected, preprocessed and integrated. (B) Data was further transformed and selected features of each data type were extracted, integrated and one-hot encoded. (C) Machine learning methods were applied to analyze and classify autoimmune diseases. The various models were validated and evaluated.

Data types provide insights to reduce data dimensionality and identify

Relevant features

We have integrated various data types that differ in structure and quality. Therefore, we harmonized the data differences through pre-processing procedures. First, we identified from each different data type the relevant features. We then integrated the features. This preprocessing resulted in the same feature space for each patient. By incorporating synthetic samples to each data type, we ensured that all patients had a standardized input of features. To enhance the successful reuse of clinical health data, we addressed challenges highlighted by Ferro et al.40. These include capturing and integrating data from various hospitals, accurately processing feature types through feature selection methods, combining features at the lowest common granular level, and handling missing data by exploring various methods and using imputation. Clinical data included four different types of variables, with numeric values representing 67.58% (Fig. 2A). To integrate categorical variables effectively, they were transformed into a uniform data object type, specifically numerical, representing the entire dataset. Laboratory data (Table S2) were used to identify similarities across samples using principal component analysis (PCA) for clustering. The first two principal components, capturing 4.46% and 3.35% of the total variance respectively, revealed a notable difference between autoimmune and non-autoimmune patients, forming two distinct clusters. When autoimmune patients were separated into their sub-disease groups, the differentiation was not substantial, resulting in several overlaps from patients with different disease classes in the same cluster (Fig. 2B).

Analysis of integrated clinical, laboratory and omics data. (A) Summary statistics of clinical data showed the distribution of clinical data types and identifies non-informative data objects for reduction of data. (B) PCA of cytokine concentrations in AID and non-AID patients. Laboratory data differentiated autoimmune and non-autoimmune patients. However, cytokine concentrations overlapped when subdividing AID into disease types. (C) Immunomics germline gene analysis revealed high frequency of certain combinations of V and J genes across cohorts, where red indicates a high frequency and light blue a low frequency. (D) Top panel: The cumulative degree frequency (CDF) distributions of CDR3 (a.a.) similarities in B-cell repertoires of representative samples of AID patients showed a mixed power-law (orange) and Poisson (gray) distribution in SLE. Bottom panel: power-law and exponential (red) degree distribution in RA. (E) Complexity of genomics data for diagnosis was largely reduced by applying preprocessing additional filtering procedures (see Methods). (F) Concentration of altered metabolites in AID comparing HC (green bar), and arthritis cohorts (red and blue bars). Dark blue indicates a high concentration of metabolites and light blue indicates a low concentration of metabolites. The clustering resulted in distinctive clusters. HC cohort cluster was clearly separated from the remaining cohorts.

This lack of clear separation underscores the need to incorporate deeper genetic understanding of AIDs. Genomics has progressed the understanding of the genetic basis for various AIDs. Research efforts have been directed at discovering common variations. These are genetic variations not primarily associated with autoimmune-specific conditions. Specifically, variations with a minor allele frequency (MAF) value range of 0.5–5% in the population are typical of AIDs41. We selected MAF ≤ 1% according to clinical best practices. To further reduce genetic variant features, we applied filtering methods based on the predicted functional consequences of specific genetic variants (Table S3). Specifically, AID samples showed an increased number of variants on chromosomes 3, 6, 7 and 14 (Fig. S4). Autoimmune patients had fewer long indels but a higher proportion of shorter mutations such as insertions and deletions compared to healthy individuals (Fig. S5). Based on this information, it was feasible to substantially reduce the number of derived genomic features (Fig. 2D, Table S4), lowering the risk of generating noise.

In immunomics, BCR sequencing investigations revealed enrichment of certain IGHV gene family usages, especially among their gene subfamilies. Several gene subfamilies have been found to be closely tied to autoimmunity8. IGHV4-34 and IGHV3-30 V genes subfamilies were prevalent in autoimmune patients8,42,43. We analyzed the frequency of V genes at the family and subfamily level, validating the patterns of expression observed in literature in comparison to the control group (Fig. S3A, S3B). Compared to healthy controls, we observed a substantial increase in IGHV1-69, IGHV4-34, IGHV4-39, IGHV4-59, and IGHV4-61 in SLE patients. In contrast, the SLE group had a considerably lower level of IGHV3-23 than the healthy cohort. Importantly, RA patients had higher frequencies of IGHV1-69, IGHV4-39, and IGHV5-51 and lower levels of IGHV3-23 and IGHV4-34 compared to healthy individuals (Fig. S3B, Table S5). Additionally, we evaluated expression of J genes. We noticed an evident decrease in IGHJ4 in both SLE and RA autoimmune groups, as well as a rise in the frequency of IGHJ3 for AID patients and a modest increase in the frequency of IGHJ1 (Fig. S3A). Network analysis revealed an altered degree distribution between autoimmune patients and the control cohort (Fig. 2C). Frequency distributions of CDR3 clones revealed that autoimmune repertoires were polarized towards few specific clones (Fig. S2A), while there is no significant difference in the CDR3 a.a. length distributions across cohorts (Fig. S2B). Antibody repertoires of healthy individuals showed an exponential sequence similarity degree distribution44. We observed that autoimmune repertoires exhibit mixed degree distribution fits, potentially indicating the repeated exposure of the patient to its autoantigens over several cycles, resembling a mix sequence space architecture between a healthy (exponential in RA, interestingly Poisson in SLE) and an immunized repertoire (powerlaw, Fig. 2C). After immunization or infection, it is expected that immune repertoires will revert to a powerlaw distribution. These networks are centered around key CDR3 nodes, suggesting that network hub clones may be targets for precision therapeutic interventions to alter disease development at the repertoire level44. Integrating immunomics data underscores the potential of CDR3 sequences as diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic biomarkers.

Metabolomics data was analyzed by clustering the concentration levels of several targeted metabolites across samples from 3 cohorts of HC, RA and PsA (Fig. 2F, Table S6). The results revealed that specific metabolites (i.e., Dl-dihydrosphingosine, turmerone, glycerol1-hexadecanoate, epsilon caprolactam, palmitic acid, phytenate, palmitoylethanolamide, hexadecasphinganine, hexadecanamide, kynurenic acid, deoxyadenosine, Dl-Ala-Dl-Ala, glycocholate, oxoproline, lysophosphatidylethanolamine, dihydrosphingosine, cholesterol) with higher concentrations in the HC group determined the clustering of these individuals together. Autoimmune patients formed two mainly separated clusters with few interspacing samples. Certain metabolites with higher concentrations in the healthy cohort are known to favor anti-inflammatory effects, consistent with their greater occurrence in HC45,46. Typical concentrations of metabolites determined the separation of autoimmune and control samples in distinct clusters, and clustering with certain degree of overlap among autoimmune cohorts. Metabolites that clearly distinguished healthy individuals from arthritis patients were compared to metabolites from research that examined healthy individuals and SLE patients47. We reported the distinguished metabolites of SLE and RA (Table S6) as predictor features for this data type.

Further, after the data transofrmation and encoding of the data types was completed, the encoded features showed specific patterns in each data type. Out of several millions of potential inputs, our integrated dataset encoded a total of 84 unique variables, including 24 clinical, 13 laboratory, 9 genomic, 21 immunomic, and 17 metabolomic features. These features were derived from the previously described analysis (e.g., V and J gene pattern analysis). Across all patient data, the one-hot encoding method produced a total of 10 614 of “1” values and 24 414 of “0” values. The ratio of “1” and “0” values was found to be approximately the same across the majority of data types for healthy individuals and AID patients. Interestingly, immunomics and metabolomics data were more balanced in amounts “0” and “1” values in samples from autoimmune patients compared to all samples (including healthy controls) when compared to clinical, laboratory and genomic data (Fig. 3A). In order to understand this observation further, we investigated at the differences in encoding results, expressing them in percentages (Fig. 3B). Examining the distribution of the labels “0” and “1” by data type, we found that when referring exclusively to the AID cohort, there is only a negligible change in the data categories “Clinical,” “Laboratory,” and “Genomics” compared to the total number of patients. In the immunomics and metabolomics data, however, the hit-encoded values “1” were approximately 75% higher. It showed, that autoimmune patients more likely exhibited notable deviations in immunomics and metabolomics features, but not in other data types. This suggests the need not to overlook the interrelationship between immune data and metabolites, which is known to be a vital aspect of personalized medicine.

Encoding of integrated clinical, laboratory and multi-omics data. (A) After binary encoding, the retrieved characteristics exhibited a comparable pattern of normally distributed values “0” in the 5–95th percentile and potentially disease-relevant values (anomalies) “1” in the < 5th and > 95th percentile across all data categories. (B) Clinical data, immunomics, and metabolomics revealed a prevalence of “1” encoded values. Genomics and laboratory data on the other hand were observed to be rather rare across all patients. (C) Although laboratory results within < 5th and > 95th percentile were seldom detected overall within the top 15 features, some of these were among the highly ranked features in samples classified as autoimmune.

Furthermore, we examined which “1” features were mostly represented in all samples (including HC) and AID-specific samples. In samples including healthy patients, more than half of the 30 most frequent reported features were clinical or lab data, while in AID samples, only one-fifth of these were clinical or laboratory data (Fig. 3C). In both groups, immunomics had a comparable number of frequent “1” encoded features. In contrast to the group including the healthy control cohort, a notably largerproportion of the top frequent characteristics were allocated to metabolomics data in the AID cohort. Out of 21, 12 immunomic features were reported as ‘1’ values in the AID group compared to all samples. Among the 17 represented metabolites, 11 showed ‘1’ values in the AID group, compared to 5 in the all-samples group. This highlighted the impact of metabolomics in feature representation for integrated clinical, laboratory, and omics data analysis.

Performance evaluation of machine learning models applied to integrated data

Machine learning methods such as Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), Stochastic Gradient Descent Classifier (SGD), Neural Networks (NN), and Support Vector Machines (SVM) were used to analyze and assess the performance of the various algorithms on multiclassification problems for the prediction of AIDs. The majority of these models were based on a collection of common ML algorithms designed to examine health data48. We calculated the prediction accuracy of the five models using a single data type, such as clinical data, and compared it to the accuracy of the same models applied to multiple data types, including clinical, laboratory, and genomics data (Fig. 4).

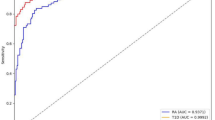

Machine learning methods applied to integrated data. (A) ROC curve calculations using autoimmune data revealed how different types of data impact the performance of machine learning model with a representative example of a random forest classifier. AUC increased once clinical data was integrated to additional data types such as laboratory and genomics. (B) The performance of selected classifiers was evaluated and compared using stratified cross-validations, revealing an improvement in prediction accuracy for each model when integrated data is used compared to a single data type.

The objective was to classify whether a sample was predicted as healthy (HC), Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), or Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). The prediction accuracy of the classification and AUC-values were compared to define the best performing model on datasets containing either a single data type or multiple data types.

We determined the macro- and micro-average AUCs of a decision tree algorithm from clinical data and from an integrated dataset of clinical, laboratory and genomics data (Fig. 4A, Fig. S1). Results indicated the highest AUC values with integrated data (right panel). Minimal differences between the models suggested no significant class imbalance. Increased performance was observed with metabolomics and especially immunomics alone; however, these did not exceed the AUC values of the integrated dataset (Fig. S6).

In addition, the accuracy of all classifiers was determined by 5-fold and 10-fold cross-validation. The results were compared using both individual data types and integrated data (Fig. 4B, Fig. S7). The prediction accuracy median values were lower (predominantly around 75–80%) when only a single data type like clinical data was incorporated. A difference in performance between the individual algorithms was shown, with LR, NN and RF performing better. The performance of all examined classifiers increased up to median accuracy of 96% when ML models were applied to an integrated dataset comprising clinical, laboratory, and genomics data. This prediction score was higher compared to the models applied to individual data types.

Furthermore, weighting of feature importance generated by grid search cross-validated Random Forest classifier was applied to integrated dataset containing clinical data, laboratory data and multi-omics data—namely genomics, immunomics and metabolomics—ranked parameters on their importance towards the multi-class prediction of healthy, SLE or RA and in the binary classification of SLE and RA. Contrary to utilizing default parameters for our model, the objective was to simulate an optimized setting where multiple data types were available and hyperparameters were fine-tuned. The focus was to discern the impact that individual data types would exercise on performance when operating within this type of scenario. Feature importance revealed that metabolomic data, when available, were the most important datatype for the prediction of RA patients. On the other hand, clinical, laboratory and immunomics features have different weights of importance among the 15 most important features for the classification of healthy and autoimmune cohorts (Fig. S8). These results further illustrate the potential of data integration for precise diagnostics.

Discussion

Access to multi-omics data has brought about a transformative shift in biomedicine, driving advancements in systems biology and deepening our understanding of biological phenomena. The integration of multi-omics to clinical and laboratory data is essential for personalized medicine, along with the potential inclusion of exposomes. Procedures to overcome related challenges hold the promise to enhance clinical advantages from outputs of omics facilities13. To address the persistent challenges to harmonize diverse data in life sciences, we developed a pipeline to combine various types of datasets. This framework integrates complex omics datasets with clinical and laboratory information. Notably, the issues that our pipeline addresses have been recognized also across recently developed methodologies that merge multi-omics with clinical data. This integration schema not only tackles the complexities arising from data heterogeneity and differing scales intrinsic to multi-omics investigations, but also supports future concurrent strategies32,49,50,51. The capacity to integrate and synthesize such data from various sources carries the potential to expand evidence-based medical studies, therefore offering a competitive advantage in the field of clinical research52. Moreover, our approach to incorporate diverse data types holds the promise to discriminate better between specific autoimmune disorders and other diseases that mimic their clinical manifestations. Our approach builds upon the need to develop and refine existent multi-omics integration procedures49,53, and emphasizes the inclusion of clinical data alongside the complex integration of multi-omics datasets. Given the overlap of symptoms characteristic of various AIDs, including RA and SLE, the advancement of robust data integration methodologies is imperative for the enhancement of diagnostic algorithms across a broad spectrum of diseases.

This adaptable framework readily accommodates additional data types by establishing guiding principles. For example, lipidomics has shown promising results to enhance diagnostic capabilities54. This omics type of data can be promptly integrated in the framework proposed here due to similar preprocessing and encoding methods. This convergence demonstrates a contextually nuanced and straightforward applicability, thereby distinguishing it from initial frameworks dedicated to analogous data integration paradigms. However, while our pipeline demonstrates broad applicability, its efficacy regarding the use of synthetic data and digital patients necessitates further investigation and validation within specific clinical contexts. Additionally, variations in the amount of available data among different data types that necessitate the use of synthetic patient data raise the potential concern of removing biological dependencies from the original data, thereby compromising their significance. Furthermore, the assumption of independence across characteristics might not be applicable in the real-world scenario. Future research should explore methods to generate synthetic data that account for biological relationships among characteristics. Another limitation involves the risk of overfitting when expanding the feature set with additional data types. Careful consideration of the selected features is essential.

The holistic approach of the integration platform presented here enables researchers to gain comprehensive insights into disease complexities. This platform allows for benchmarking of new ML methods, paving the way for advanced diagnostic strategies.

Our adaptable data integration framework enhances personalized medicine by integrating diverse data types. This development supports advancements in technologies such as IoT in healthcare. Its utility extends to the continuous integration of real-time data from wearable devices and smart sensors, which can be harnessed to improve patient care and monitoring55. Moreover, this framework leverages computational techniques that empower accurate disease diagnosis, targeted treatment planning, and efficient resource allocation. Such developments underline the potential of technology-driven approaches for healthcare resilience against global challenges and to accelerate the advancement of personalized treatment strategies56. The value to further develop integration procedures together with nature-inspired optimization methods such as Particle Swarm Optimization and Genetic Algorithms is crucial for addressing complex healthcare problems including disease prediction and resource allocation57. Given the increased adoption of such integrative approaches in healthcare for diverse biological challenges and disease understanding58,59,60, further investigation and applications of these methods could lead to more personalized and effective healthcare interventions. However, the efficient application of the integration pipeline and the ML methods presented here, further depend on the implementation of nationwide semantic and technical interoperability standards. Future developments of this pipeline can accelerate the integration of additional multi-omics data, nutritional data and digital biomarkers into next-generation EHR solutions, as well as foster its use in clinical decision support systems.

Materials & methods

The present study utilized patient data to investigate and evaluate data integration, along with subsequent applications of ML methods. The representative patient data were sourced from multiple sources and hospitals. Datasets I-IV were accessed through the University Hospital Institutions of Strasbourg, Freiburg, and Mainz. This data were used for the design and evaluation of the pipeline’s principle and functionality. Additionally, supplementary datasets (V-XII) were collected from published studies as described below. This approach enabled a robust examination of the concept and methodology while diverse and relevant data sources for testing purposes were ensured.

Data

Clinical

Dataset I. The Rheuma-Vor App (RAPP) dataset included clinical data in the form of a physician’s questionnaire from 815 patients with symptoms of rheumatoid disease, specifically rheumatoid arthritis (RA), axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Seventeen questions were designed to refute or confirm suspicion of one of these three AIDs. These diseases are among the most common inflammatory joint diseases, which pose a major challenge for rheumatologists in terms of diagnosis, treatment and monitoring61.

Dataset II. The Lupus BioBank of the upper Rhine valley (LBBR) database contained clinical and biological information (serum, plasma, DNA, cells) on 1300 patients with autoimmune disorders. Patients were diagnosed with several types of AIDs, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis (SS). This data was gathered from 17 hospitals in the upper Rhine region in France and Germany. Since the original dataset contained missing data, a subset of 215 SLE patients with full data and a Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) score of at least 6 was extracted. The SLEDAI is a scoring system used to assess the disease activity and severity, and a score 6 can result from a combination of moderate manifestations across different categories of the scoring system.

Laboratory

Dataset III. Bead-based multiplex assays were employed to measure concentrations of cytokines, chemokines, immunoglobulins and other biomarkers to provide information about their expressions in AID patients. Serum data was analyzed utilizing BioLegend LEGENDplex™ Data Analysis Software. Results represent the concentration expressed in pg/mL, if not indicated otherwise. The data was generated from samples of 23 SLE patients.

Genomics

Dataset IV. For whole exome analysis, Genomic DNA was extracted from blood using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Exomic regions of the DNA were enriched using the SureSelect Human All Exon Kit V5 (Agilent Technologies), TruSeq Exome Kit (Illumina) or Twist Core Exome (Twist Bioscience). The enriched exome samples were sequenced using Paired-end (2 × 75 bp) sequencing on a NextSeq500 Illumina sequencer. Exome data from one SLE patient and a control group of 96 healthy donors was generated and provided by the Strasbourg University Hospital. All participants gave their informed consent, and the study was approved by the University Hospital institutional review board.

Dataset V. WES on 32 systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients using the Nimblegen SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library v3.0 Kit was performed from The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)62. Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using QIAGEN Puregene Blood Kits. Library preparation was performed using NuGEN Ovation Ultralow Library Systems or the Nextera DNA Sample Preparation Kit. Sequencing of 100 bp paired-end reads was conducted on an Illumina HiSeq 2000.

Immunomics

Dataset VI. Samples from five RA patients were gathered according to Stanford University or the University of Pittsburgh methods approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). The subjects satisfied the 1987 and 2010 standards established by the American College of Rheumatology. PBMCs were separated using density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Paque™ PLUS (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) or Lympho-prep (Axis-shield). Heavy chain and light chain genes were amplified using gene-specific PCR primers, then 2 × 300 paired-end reads were sequenced with Illumina MiSeq63.

Dataset VII. Serial blood samples of eight participants with established RA who tested positive for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) using an anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide assay were obtained in heparin tubes after obtaining written informed permission from all possible research participants in accordance with methods authorized by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board42. Patients with RA satisfied the 1987 and 2010 American College of Rheumatology categorization criteria. Heavy chain and light chain genes from plasmablasts were amplified from pooled cDNA using gene-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers and 2 × 300 paired-end reads were sequenced with Illumina MiSeq.

Dataset VIII. SLE patients were recruited if they were classified as having a moderate-severe flare according to the SELENA-SLEDAI flare index. Furthermore, they were receiving minimal immunosuppression at the time of the flare. All SLE patients met the EULAR/ACR classification criteria, which are often used to establish the diagnosis of SLE by experienced rheumatologists. Data was generated as described by Tipton et al.64. Briefly, approximately 0.1–3 × 105 mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood of eight SLE patients experiencing acute flares. Total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA and library amplificons were sequenced with Illumina MiSeq 250 × 2 or 300 × 2.

Dataset IX. PBMCs from SLE patients (N = 3) and healthy controls (HC, N = 3) were isolated from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus65. B cells were isolated using the 10X Chromium Controller. The V(D)J Enrichment for Human B-cells (version 1.1) and the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell5’ Library kits were used to generate V(D)J-enriched libraries which were sequenced on a NovaSEQ 6000 (Illumina) with 2 × 150 paired-end reads.

Dataset X. Memory B-cells (CD19+, CD27+) were isolated from peripheral B-cells of 7 healthy donors, and RNA was transcribed into cDNA. Immunoglobulin-specific primers were used for PCR amplification and subjected to high-throughput sequencing of 2 × 300 bp paired-end reads with the Illumina MiSeq platform66.

Dataset XI. Five pairs of adult monozygotic, twins (N = 10) provided written informed consent to participate in research on seasonal influenza vaccinations at Stanford University School of Medicine. PBMCs were extracted from their peripheral blood and memory B-cells were identified based on CD20 and CD27 expression. Only one sample from each twin pair was used for the study, resulting in a total of 5 samples67. Sequencing was performed with Illumina MiSeq 2 × 300 bp paired-end reads.

Metabolomics

Dataset XII. Metabolic profiling of fecal samples was performed by Wang et al.68 using a UHPLC (ExionLCTM AD) in conjunction with a Triple TOF 5600 + mass spectrometer (American, AB Sciex). Chromatographic separation was done with a Waters Acquity UPLC HSS T3 (1.8 mm, 2.1 × 100 mm). Column temperature was set at 40 °C and the injection volume corresponded to 5 µl. For data acquisition, full scan mode as well as positive and negative ion modes were coupled with information dependent acquisition (IDA) modes that triggered production scans. The full scan range was defined to 100–1500 m/z and ion scan range to 50-1250 m/z with high sensitivity.

Preprocessing and annotation

Clinical data

The data were anonymized and preprocessed to remove erroneous values and missing data. Categorical characteristics were transformed in nominal values where numbers were used as labels for distinct categories, while numerical characteristics were transformed into discrete categories.

Laboratory

Given the dataset exclusively comprised patients diagnosed with an autoimmune condition (N = 23), it was essential to construct a new dataset. This new dataset integrated synthetically generated digital healthy and autoimmune patient data with existing cytokine measurement data from autoimmune patients. Each synthetic patient received a unique identifier associated with a specific classification target: SLE, RA, or HC (healthy control). In simulating healthy patients, random values within the defined healthy range—based on the minimum, maximum, and mean concentrations of soluble mediators—were employed. Only values within this established range were considered.

Genomics

Sequencing reads were aligned to the human genome sequence assembly hg19 using the Burrows-Wheeler Alignment tool (BWA)69. The alignments were converted from a sequence alignment map (SAM) format to be sorted and indexed to binary alignment map (BAM) files (SAMtools versions 1.7 to 1.8)70. Duplicate reads were removed using Picard 2.21.9. Local realignments around insertions or deletions and base quality score recalibration were performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) 3.2-2. Small indels were identified using the GATK HaplotypeCaller and filtered according to the best-practice guidelines of the Immunology Laboratory, University Hospital of Strasburg71. Variants that passed the filters (Table S3) were annotated with Variant Effect Predictor (VEP), the Ensembl variant effect predictor72.

Immunomics

Antibody raw read sequences were VDJ annotated with IgBLAST version 1.17.073. Heavy chains were analyzed as the major determinant for clonal type definition and antigen-binding74. Several steps to preprocess samples were applied in order to increase data quality75. Clonotypes were only retained if they were functionally productive, composed of at least four amino acids (a.a.), and had a minimal read count of two76. The IgBLAST algorithm marks a sequence as productive only if it contains no stop codons and if it is in-frame (the last coding triplet for the V gene in the query is in-frame with the first complete coding triplet for the J genes). Moreover, the removal of unique CDR3 sequences has the potential to enhance sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity reflects the extent to which each sequence pattern represents the diversity within immune sequences of a single cluster, while specificity indicates the proportion of immune sequences from other clusters that are accurately identified and excluded77. Clones were defined by 100% a.a. sequence identity of CDR3 regions.

Metabolomics

Raw data was imported into XCMS (version 3.6.3) to perform automatic data preparation, i.e., peak picking and retention time correction. Metabolites were identified and mapped using OSI/SMMS software (Dalian ChemData Solution Information Technology Co., Ltd., PR China), Human Metabolome Database (http://www.hmdb.ca/), Lipidmaps (https://lipidmaps.org/) and LipidBlast (https://fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu/projects/lipidblast)68.

Synthetic data generation

To address the issue of sample imbalance in our datasets, we implemented an oversampling approach78. Our largest dataset, the RAPP dataset (Dataset I, see Methods), served as the benchmark reference for the oversampling due to its sample size (N = 815). The principal objective was to align the sample counts of smaller datasets with the reference count, ensuring a standard sample size across all datasets. In scenarios where the sample counts from other datasets were less than the reference count, we generated synthetic samples. This iterative process of synthetic sample generation continued until the total count within each subset equated to the reference count of 815. The motivation is to reach homogeneity across all datasets, enabling a normalized comparative analysis of the results derived from equally distributed datasets. In line with the clinical dataset’s target labels, the number of synthetic digital patients was adjusted in each data type, resulting in 398 HC, 215 patients with the label “SLE,” and 202 patients with the label “RA.” To match the targeted oversampling approach for laboratory data, synthetic patients were generated by determining healthy and unhealthy ranges of 45 distinct soluble mediators following a Gaussian distribution. The ranges of mediators were defined by minimum, maximum and mean concentration values, and by applying a standard deviation of \(\:\sigma\:=\frac{max-\mu\:}{2.2}\), in which disease-specific patterns of concentration values of cytokines and chemokines were used to generate synthetic samples79. Synthetic omics data was generated by synthetic data vault (SDV) GAN model in accordance with the anticipated oversampling strategy80.

Encoding

Encoding of categorical data

Data sets primarily composed of categorical values, typically clinical data from health questionnaires, were converted to binary format. Most questions had “yes” or “no” responses, allowing direct transformation of these variables into a binary state, “1” or “0”. Responses not explicitly marked as “yes” in the original EHR data were categorized as “no” in the binary conversion.

Accumulation-based encoding

Encoding on a categorical basis was not a feasible approach to transform the remaining laboratory and omics data into a binary form, as this was not compatible with the intended data integration strategy of dimensionality reduction33.

To address this challenge, we developed a method for binary encoding based on the cumulative values of each attribute as illustrated in supplementary Fig. S1. Prior investigations on B-cell sequencing have highlighted abnormal occurrences of specific heavy chain genes in autoimmune patients, particularly with notable enrichments of certain gene families8. Anomalies were detected by assessing the extent to which the enrichment of specific features, such as for example the expression levels of certain V or J genes or the concentration level of certain metabolites, deviated significantly from the average. These anomalies were labeled as “1” and deemed conspicuous within our binary encoding framework. To establish the abnormality range, previous studies have employed the inter-percentile range between the 5th and 95th percentiles when analyzing omics data81,82,83. We adopted this methodology consistently adopted whenever it applicable to data that could be meaningfully accumulated and deemed suitable for the specific features under consideration. This methodology proves insufficient when categorical variables are inclued, necessitating the alternate approach described in the section “Encoding of Categorical Data.”

Dimensional reduction techniques

The rapid introduction of a high number of features is one of the challenges in integrating omics data. To apply ML to integrated data efficiently, data models are required to be as simple as possible. The following analytic techniques were used to establish relevant characteristics based on data types, which were then used in data integration.

PCA of soluble mediators’

Cytokine measurements were decreased in dimensionality and scaled to two principal components per feature using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). These reflect the variance of each sample to the mean and were calculated using StandardScaler from the Sklearn package version 1.0.2.

Gene frequency distribution

The annotated immunoglobulin repertoire data were analyzed for their abundance level using R version 4.1.2 in Rstudio build 351. The frequency of V and J genes was calculated as the occurrence of the specific gene family and subgroup of a sequence in a sample, and in a cohort. CDR3 sequences frequency was calculated sample- and cohort-wise. CDR3 diversity as cumulative frequency and networks were calculated for each sample.

Network analysis of immune repertoire

A network analysis of CDR3 sequences (a.a.) was conducted to examine the clonal sequence space architecture for each patient group, following established methodologies44. The antibody network degree distribution was calculated based on the Levenshtein distance (LD) between CDR3 sequences. Nodes representing similar CDR3 sequences were connected if they had an LD of 1, indicating a difference of a single amino acid. To optimize feature selection for ML, networks were used to identify a subset of sequences that accounted for a large portion of the sequence diversity, while minimizing the impact of less authoritative sequences in the network.

Metabolite analysis

Numerical peaks of 95 positively ion mapped metabolites from 36 HC, and 56 arthritis patients, namely 29 RA patients and 27 PsA patients, were read in using Pandas version 1.4.1. Data were normalized and fit using MinMaxScaler from Sklearn version 1.0.2. The different metabolites were presented in a heat map representing the abundance level of expressed metabolites and were simultaneously organized with hierarchical cluster analysis using Seaborn version 0.11.2, resulting in a Clustermap (Fig. 2E).

Machine learning models

Dimensionality reduction methods, including feature extraction and selection, were used to optimize training in multi-omics datasets with fewer observation samples than features. Feature extraction was used to transform a subset of inputs into a feature, while feature selection was performed to identify within original features ones that maximize the accuracy of predictive models37,84. The analysis involved the application of the supervised machine learning (ML) methods Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), Stochastic Gradient Descent Classifier (SGD), Neural Networks (NN), and Support Vector Machines (SVM). These models were applied to the preprocessed and integrated datasets. The data was divided into training and test sets, with the training set using 70% of the data and the test set using the remaining 30%85. To discern the potential benefits arising from data integration, we intentionally employed default values as hyperparameters for the respective models. This approach facilitates an understanding of the advantageous effects of data integration, even when models have not been subjected to exhaustive hyperparameter tuning. Specifically, for LR, the “liblinear” solver was used. For RF models, 200 trees were used. For SGD, 1000 iterations were performed. Deep learning has proven to be a suitable approach for processing heterogeneous and complex data. Therefore, an NN model was applied to the integrated and encoded omics dataset86. Specifically, a multilayer perceptron model that used the “relu” activation function with “adam” specified as solver, and one a hidden layer with 100 nodes, was applied. For SVM, the “poly” kernel was selected with degree 3 and cost 1. Classification accuracy, precision, sensitivity (recall), and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were used to assess the performance of all models. The AUC is a metric used in binary classification, quantifying the degree or measure of separability between classes. It tells how well a model is capable of distinguishing between classes, where a perfect classifier would have an AUC of 1.0, and a random classifier would have an expected AUC of 0.5. Classification accuracy, precision, sensitivity (recall), and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were used to assess the performance of all models (see supplementary information, including Fig. S6 and S7)87. The experiments were designed to address a multiclass classification problem. Using the available data models, the respective classifiers ought to be able to predict as precisely as possible whether a patient has one of the two AIDs “RA” or “SLE”, respectively, or whether they could be considered healthy “HC.” In order to maintain data integrity and enhance experiment reliability, few samples with labels indicating other AIDs, such as “PsA”, “SpA” or “SS,” which were present only in certain datasets, were deliberately excluded from the ML analysis. By prioritization the use of robust and more complete datasets, our approach minimized the need to generate synthetic data. Both macro- and micro-average AUC were calculated and ROC curves generated to evaluate classifier performance (Table S1)88. These metrics are critical in ML, especially with imbalanced class sizes. Macro-average AUC calculates the AUC for each class independently and averages these values, providing an overall assessment of discriminative ability across multiple classes, irrespective of class size. Micro-average AUC aggregates the true positive, false positive, and false negative rates across all classes before calculating the AUC, thus reflecting the global performance of the model across all classes by weighing each sample equally. As our data sets had a balanced proportion of AID and non-AID patients (AID = 417 patients, non-AID = 398), but a minor imbalance in the number of samples across all three cohorts (HC = 398, RA = 202, SLE = 215), we examined both scores concurrently. Training and validation were performed with k-fold cross-validation (k = 5 and k = 10, Fig. 4 shows results with k = 10). The classifiers employed in this study are adapted from the python library scikit-learn.

Code and data availability

All scripts are available in the aiHealthLab’s GitLab repository upon request to Enkelejda Miho (enkelejda.miho@fhnw.ch). Anonymized clinical and genetic data contributed by collaborators can be shared upon justified request to Enkelejda Miho (enkelejda.miho@fhnw.ch). Data obtained from public sources is specifically indicated throughout the text and referenced to the original publication.

Data availability

All scripts are available in the aiHealthLab’s GitLab repository upon request to Enkelejda Miho (enkelejda.miho@fhnw.ch). Some of the patient clinical and genetic data were contributed by collaborators and can be shared upon justified request from Enkelejda Miho (enkelejda.miho@fhnw.ch). Data obtained from public sources is specifically indicated throughout the text and referenced to the original publication.

References

Sinha, A. A., Lopez, M. T. & McDevitt, H. O. Autoimmune diseases: the failure of Self Tolerance. Science. 248, 1380–1388 (1990).

Cooper, G. S., Bynum, M. L. K. & Somers, E. C. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J. Autoimmun. 33, 197–207 (2009).

Living with the enemy. Nat. Immunol. 19, 658–658 (2018).

Dinse, G. E. et al. Increasing prevalence of Antinuclear Antibodies in the United States. Arthritis Rheumatol. 72, 1026–1035 (2020).

Greiner, W. et al. High-expenditure disease in the EU-28: does drug spend correspond to clinical and economic Burden in Oncology, Autoimmune Disease and Diabetes? PharmacoEconomics - Open. 5, 385–396 (2021).

Keskin, E., Öğretim, Ü., İnci, Z. & Gökbay Clinical Decision Support Systems in Diagnosis of Autoimmune Diseases. doi: (2020). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.18411.08481

Anne, D., Betty, D., Autoimmune & Diseases N Engl. J. Med. 11 (2001).

Bashford-Rogers, R. J. M., Smith, K. G. C. & Thomas, D. C. Antibody repertoire analysis in polygenic autoimmune diseases. Immunology. 155, 3–17 (2018).

Arbuckle, M. R. et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic Lupus Erythematosus. N Engl. J. Med. 349, 1526–1533 (2003).

Song, R., Jia, X., Zhao, J., Du, P. & Zhang, J. T cell receptor revision and immune repertoire changes in autoimmune diseases. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08830185.2021.1929954 (2021).

Nagafuchi, Y., Shoda, H. & Fujio, K. Immune Profiling and Precision Medicine in systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Cells. 8, 140 (2019).

Tipton, C. M., Hom, J. R., Fucile, C. F., Rosenberg, A. F. & Sanz, I. Understanding B-cell activation and autoantibody repertoire selection in systemic lupus erythematosus: a B-cell immunomics approach. Immunol. Rev. 284, 120–131 (2018).

Alyass, A., Turcotte, M. & Meyre, D. From big data analysis to personalized medicine for all: challenges and opportunities. BMC Med. Genomics. 8, 33 (2015).

Hasin, Y., Seldin, M. & Lusis, A. Multi-omics approaches to disease. Genome Biol. 18, 83 (2017).

Angermueller, C., Pärnamaa, T., Parts, L. & Stegle, O. Deep learning for computational biology. Mol. Syst. Biol. 12, 878 (2016).

Ahalt, S. C. et al. Clinical Data: sources and types, Regulatory constraints, applications. Clin. Transl Sci. 12, 329–333 (2019).

Overhage, J. M. & Overhage, L. M. Sensible use of observational clinical data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 22, 7–13 (2013).

Carlson, R. K. Presentation and Handling of Clinical Laboratory Data -- From Test Tube to Table 13 (2007).

Belkadi, A. et al. Whole-genome sequencing is more powerful than whole-exome sequencing for detecting exome variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 5473–5478 (2015).

Warr, A. et al. Exome sequencing: current and future perspectives. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics. 5, 1543–1550 (2015).

Ellyard, J. I. et al. Brief report: identification of a pathogenic variant in TREX1 in early-onset cerebral systemic lupus erythematosus by whole-exome sequencing: pathogenic TREX1 Deficiency in early-onset cerebral SLE. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66, 3382–3386 (2014).

Wajda, A., Sivitskaya, L. & Paradowska-Gorycka, A. Application of NGS Technology in understanding the Pathology of Autoimmune diseases. J. Clin. Med. 10, 3334 (2021).

Wise, A. L. et al. Genomic medicine for undiagnosed diseases. Lancet. 394, 533–540 (2019).

Robinson, W. H. Sequencing the functional antibody repertoire—diagnostic and therapeutic discovery. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 11, 171–182 (2015).

Gremel, G. et al. A systematic analysis of commonly used antibodies in cancer diagnostics. Histopathology. 64, 293–305 (2014).

Miho, E. et al. Computational strategies for dissecting the high-dimensional complexity of Adaptive Immune repertoires. Front. Immunol. 9, 224 (2018).

Greiff, V. et al. Learning the high-dimensional immunogenomic features that predict public and private antibody repertoires. J. Immunol. 199, 2985–2997 (2017).

Banerjee, S. Empowering Clinical Diagnostics with Mass Spectrometry. ACS Omega. 5, 2041–2048 (2020).

Sheikh, M. O. et al. Correlations between LC-MS/MS-Detected glycomics and NMR-Detected metabolomics in Caenorhabditis elegans Development. Front. Mol. Biosci. 6, 49 (2019).

Duan, R. et al. Evaluation and comparison of multi-omics data integration methods for cancer subtyping. PLOS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009224 (2021).

Liu, Y., Devescovi, V., Chen, S. & Nardini, C. Multilevel omic data integration in cancer cell lines: advanced annotation and emergent properties. BMC Syst. Biol. 7, 14 (2013).

Subramanian, I., Verma, S., Kumar, S., Jere, A. & Anamika, K. Multi-omics Data Integration, Interpretation, and its application. Bioinforma Biol. Insights. 14, 117793221989905 (2020).

Picard, M., Scott-Boyer, M. P., Bodein, A., Périn, O. & Droit, A. Integration strategies of multi-omics data for machine learning analysis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 3735–3746 (2021).

ElAbd, H. et al. Amino acid encoding for deep learning applications. BMC Bioinform. 21, 235 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Deep learning in omics: a survey and guideline. Brief. Funct. Genomics. 18, 41–57 (2019).

Horst, A. et al. Machine learning detects Anti-DENV signatures in antibody repertoire sequences. Front. Artif. Intell. 4, 715462 (2021).

Raimondi, D. et al. An interpretable low-complexity machine learning framework for robust exome-based in-silico diagnosis of Crohn’s disease patients. NAR Genomics Bioinforma. 2, lqaa011 (2020).

Hériché, J. K., Alexander, S. & Ellenberg, J. Integrating imaging and Omics: computational methods and challenges. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2, 175–197 (2019).

de López, E. et al. Challenges in the integration of Omics and Non-omics Data. Genes. 10, 238 (2019).

Ferrão, J., Oliveira, M., Janela, F. & Martins, H. Preprocessing structured clinical data for predictive modeling and decision support: a roadmap to tackle the challenges. Appl. Clin. Inf. 07, 1135–1153 (2016).

Massey, J. & Eyre, S. Rare variants and autoimmune disease. Brief. Funct. Genomics. 13, 392–397 (2014).

Elliott, S. E. et al. Affinity Maturation drives Epitope spreading and Generation of Proinflammatory anti–citrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 70, 1946–1958 (2018).

Bashford-Rogers, R. J. M. et al. Analysis of the B cell receptor repertoire in six immune-mediated diseases. Nature. 574, 122–126 (2019).

Miho, E., Roškar, R., Greiff, V. & Reddy, S. T. Large-scale network analysis reveals the sequence space architecture of antibody repertoires. Nat. Commun. 10, 1321 (2019).

Gong, T. et al. Palmitic acid-modified bovine serum albumin nanoparticles target scavenger receptor-A on activated macrophages to treat rheumatoid arthritis. Biomaterials. 258, 120296 (2020).

Jung, J. I. et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of palmitoylethanolamide ameliorates osteoarthritis induced by monosodium iodoacetate in Sprague–Dawley rats. Inflammopharmacology. 29, 1475–1486 (2021).

Zhang, Q. et al. Fecal metabolomics and potential biomarkers for systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front. Immunol. 10, 976 (2019).

Stafford, I. S. et al. A systematic review of the applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in autoimmune diseases. Npj Digit. Med. 3, 30 (2020).

Wang, C., Lue, W., Kaalia, R., Kumar, P. & Rajapakse, J. C. Network-based integration of multi-omics data for clinical outcome prediction in neuroblastoma. Sci. Rep. 12, 15425 (2022).

Jin, T. et al. scGRNom: a computational pipeline of integrative multi-omics analyses for predicting cell-type disease genes and regulatory networks. Genome Med. 13, 95 (2021).

Cao, Z. J. & Gao, G. Multi-omics single-cell data integration and regulatory inference with graph-linked embedding. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1458–1466 (2022).

Gomez-Cabrero, D. et al. Data integration in the era of omics: current and future challenges. BMC Syst. Biol. 8, I1 (2014).

Cai, Z., Poulos, R. C., Liu, J. & Zhong, Q. Machine learning for multi-omics data integration in cancer. iScience. 25, 103798 (2022).

Cas, M. D., Roda, G., Li, F. & Secundo, F. Functional lipids in Autoimmune Inflammatory diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3074 (2020).

IoT in Healthcare and Ambient Assisted Living. vol. 933 (Springer Singapore, Singapore, (2021).

Computational Intelligence Techniques for Combating COVID-19. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, doi: (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68936-0

Nature-Inspired Methods for Smart Healthcare Systems and Medical Data. (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, doi: (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-45952-8

Vasaikar, S. V. et al. A comprehensive platform for analyzing longitudinal multi-omics data. Nat. Commun. 14, 1684 (2023).

Jian, C. et al. Comprehensive Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals the Core Role of Glycerophospholipid Metabolism in Rheumatoid Arthritis Development. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.15.528612 doi:10.1101/2023.02.15.528612.

Forrest, I. S. et al. A machine learning model identifies patients in need of autoimmune disease testing using electronic health records. Nat. Commun. 14, 2385 (2023).

Kerola, A. et al. Psoriatic arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in Norway: nationwide prevalence and use of biologic agents. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009742.2021.1997436 (2022).

Mak, A. C. Y. et al. Brief report: whole-exome sequencing for identification of potential causal variants for diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: IDENTIFICATION OF POTENTIAL dcSSc CAUSAL VARIANTS WITH WES. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68, 2257–2262 (2016).

Elliott, S. E. et al. B cells in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissues encode focused antibody repertoires that include antibodies that stimulate macrophage TNF-α production. Clin. Immunol. 212, 108360 (2020).

Tipton, C. M. et al. Diversity, cellular origin and autoreactivity of antibody-secreting cell population expansions in acute systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Immunol. 16, 755–765 (2015).

Peterson, J. N. et al. Elevated detection of dual antibody B cells identifies Lupus patients with B cell-reactive VH4-34 autoantibodies. Front. Immunol. 13, 795209 (2022).

Vander Heiden, J. A. et al. Dysregulation of B cell repertoire formation in Myasthenia Gravis patients revealed through deep sequencing. J. Immunol. 198, 1460–1473 (2017).

Rubelt, F. et al. Individual heritable differences result in unique cell lymphocyte receptor repertoires of naïve and antigen-experienced cells. Nat. Commun. 7, 11112 (2016).

Wang, N. et al. Altered fecal metabolomics and potential biomarkers of Psoriatic Arthritis Differing from Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 13, 812996 (2022).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ Data to high-confidence variant calls: the genome analysis Toolkit Best practices Pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma 43, (2013).

McLaren, W. et al. The Ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 122 (2016).

Ye, J., Ma, N., Madden, T. L. & Ostell, J. M. IgBLAST: an immunoglobulin variable domain sequence analysis tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W34–W40 (2013).

Zhou, J. Q. & Kleinstein, S. H. Immunoglobulin Heavy Chains are sufficient to Determine Most B Cell Clonal relationships1. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1101/665760 doi:10.1101/665760.

Smakaj, E. et al. Benchmarking immunoinformatic tools for the analysis of antibody repertoire sequences. Bioinformatics. 36, 1731–1739 (2020).

Greiff, V. et al. Quantitative assessment of the robustness of next-generation sequencing of antibody variable gene repertoires from immunized mice. BMC Immunol. 15, 40 (2014).

Thakkar, N. & Bailey-Kellogg, C. Balancing sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing TCR groups by CDR sequence similarity. BMC Bioinform. 20, 241 (2019).

Fujiwara, K. et al. Over- and under-sampling Approach for extremely imbalanced and Small Minority Data Problem in Health Record Analysis. Front. Public. Health. 8, 178 (2020).

Stawiski, M. Machine learning methods diagnose autoimmune diseases from clinical and molecular data. (2021).

Patki, N., Wedge, R. & Veeramachaneni, K. The Synthetic Data Vault. in IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA) 399–410 (IEEE, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2016). doi: (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/DSAA.2016.49

Sigalova, O. M., Shaeiri, A., Forneris, M., Furlong, E. E. & Zaugg, J. B. Predictive features of gene expression variation reveal mechanistic link with differential expression. Mol. Syst. Biol. 16, (2020).

Bishop, M. R. et al. Genome-wide Enrichment of De Novo Coding Mutations in Orofacial Cleft trios. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 107, 124–136 (2020).

Kohsaka, H. et al. The human immunoglobulin V(H) gene repertoire is genetically controlled and unaltered by chronic autoimmune stimulation. J. Clin. Invest. 98, 2794–2800 (1996).

Reel, P. S., Reel, S., Pearson, E., Trucco, E. & Jefferson, E. Using machine learning approaches for multi-omics data analysis: a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 49, 107739 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. MOGONET integrates multi-omics data using graph convolutional networks allowing patient classification and biomarker identification. Nat. Commun. 12, 3445 (2021).

Martorell-Marugán, J. et al. A comprehensive database for integrated analysis of omics data in autoimmune diseases. BMC Bioinform. 22, 343 (2021).

Saito, T. & Rehmsmeier, M. The Precision-Recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating Binary classifiers on Imbalanced datasets. PLOS ONE. 10, e0118432 (2015).

Bihis, M. & Roychowdhury, S. A generalized flow for multi-class and binary classification tasks: An Azure ML approach. in IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data) 1728–1737 (IEEE, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2015). doi: (2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData.2015.7363944

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Sebastian Wendeborn, Andrew Brown, Kristina Djordjevic, and Nicodème Paul for their valuable input and support throughout this work. Their contributions were instrumental in the successful completion of this study.

Funding

This work has been financially supported by the Interreg Europe 2018 grant Interreg V-Projekt Nr. WO 2.2 “PERSONALIS” and Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft (NRP), Kanton Basel-Stadt, Kanton Basel-Landt, and Kanton Solothurn to Prof. Dr. Enkelejda Miho.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EM, TM, RC and JK conceived and designed the study. TM, RC, MR and RV provided clinical data. MT, AC, AM, MC, EG, AS and JM provided expert guidance on the conception and validation of the methods. EM, EN, PM, MS and JK developed the computational pipelines. JK and EM performed data analysis. All authors contributed to scientific discussions and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jan Kruta, Raphael Carapito, Marten Trendelenburg, Thierry Martin, Marta Rizzi, Reinhard E. Voll, Andrea Cavalli, Eriberto Natali, Patrick Meier, Marc Stawiski, Johannes Mosbacher, Annette Mollet, Miriam Capri, Enrico Giampieri, Aurelia Santoro and Erik Schkommodau declare that they have no conflict of interest. Enkelejda Miho owns shares in aiNET GmbH.

Ethics approval

This study, involving human participants, complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and has received approvals from the appropriate medical ethical committees. The study has been approved by the CHU Strasbourg Medical Ethical Committee under the approval number CPP- IV- Est- 08/02/2011. Participants gave their informed consent prior to their involvement in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kruta, J., Carapito, R., Trendelenburg, M. et al. Machine learning for precision diagnostics of autoimmunity. Sci Rep 14, 27848 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76093-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76093-7