Abstract

Release of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia pipientis (wMel strain) is a biocontrol approach against Ae. aegypti-transmitted arboviruses. The Applying Wolbachia to Eliminate Dengue (AWED) cluster-randomised trial was conducted in Yogyakarta, Indonesia in 2018–2020 and provided pivotal evidence for the efficacy of wMel-Ae. aegypti mosquito population replacement in significantly reducing the incidence of virologically-confirmed dengue (VCD) across all four dengue virus (DENV) serotypes. Here, we sequenced the DENV genomes from 318 dengue cases detected in the AWED trial, with the aim of characterising DENV genetic diversity, measuring genotype-specific intervention effects, and inferring DENV transmission dynamics in wMel-treated and untreated areas of Yogyakarta. Phylogenomic analysis of all DENV sequences revealed the co-circulation of five endemic DENV genotypes: DENV-1 genotype I (12.5%) and IV (4.7%), DENV-2 Cosmopolitan (47%), DENV-3 genotype I (8.5%), and DENV-4 genotype II (25.7%), and one recently imported genotype, DENV-4 genotype I (1.6%). The diversity of genotypes detected among AWED trial participants enabled estimation of the genotype-specific protective efficacies of wMel, which were similar (± 10%) to the point estimates of the respective serotype-specific efficacies reported previously. This indicates that wMel afforded protection to all of the six genotypes detected in Yogyakarta. We show that within this substantial overall viral diversity, there was a strong spatial and temporal structure to the DENV genomic relationships, consistent with highly focal DENV transmission around the home in wMel-untreated areas and a near-total disruption of transmission by wMel. These findings can inform long-term monitoring of DENV transmission dynamics in Wolbachia-treated areas including Yogyakarta.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Indonesia has one of the highest dengue burdens globally 1. Most cases are children and young adults, and an estimated 1 million dengue hospitalisations and 3000 fatal dengue cases occur on average each year 2,3,4,5. In Indonesia and elsewhere, efforts to control dengue are focussed on control of the primary vector, Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, via peri-focal insecticide spraying and larvicide use, and public education to reduce breeding sites 6. Despite decades of efforts, these control measures have been unable to prevent a trend of increasing dengue incidence and hyperendemicity in Indonesia over the past 50 years 6.

Dengue virus (DENV) exists as four antigenically and phylogenetically distinct serotypes (DENV-1–4). Serotypes are broad groupings of genetically related DENVs comprised of diverse, lower-ranked phylogenetic clades or genotypes with no more than 6% sequence divergence. To date, twenty DENV genotypes have been identified, each linked to specific geographical distributions 7,8. In Indonesia, all four DENV serotypes have been detected since the early 1970s 9,10. Prevalent genotypes, observed nationally and within Yogyakarta, include DENV-1 genotypes I and IV, DENV-2 Cosmopolitan, DENV-3 genotype I and DENV-4 genotype II 9,11,12.

Field trials conducted within cities in Australia 13,14, Indonesia 15,16, Brazil 17,18 and Columbia 19 have consistently demonstrated a reduction in dengue incidence following introgression of the obligate intracellular bacterium Wolbachia pipientis (wMel strain) into Ae. aegypti populations, during follow-up periods of 2–10 years post-release. Some of the strongest evidence supporting this approach to dengue control has been generated in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Reductions in dengue incidence occurred after releases of wMel-infected mosquitoes, initially in a quasi-experimental study 15 and were confirmed in a city-wide randomised controlled trial (the ‘Applying Wolbachia to Eliminate Dengue’ [AWED] RCT) 16. In the AWED RCT, the efficacy of wMel in reducing the incidence of virologically-confirmed dengue (VCD) was measured by applying a test-negative study design across 24 clusters, randomly allocated 1:1 to receive wMel or no treatment 20. The primary analysis of the AWED RCT data showed a reduction in the incidence of VCD by 77% and hospitalised VCD by 86% in wMel-treated areas, and that efficacy was comparable across dengue virus serotypes 16.

Vector competence studies and real-world epidemiological evidence suggest that wMel is broadly protective across DENV genotypes 16,21,22,23, however genotype-specific efficacy has not previously been formally evaluated and remains a knowledge gap. This is important because the probability of breakthrough DENV transmission occurring in a population of wMel-infected mosquitoes could be higher for some genotypes/lineages over others, plausibly leading to field selection. The AWED trial and the diversity of DENV genotypes in Yogyakarta provide a unique opportunity to calculate wMel efficacy per genotype.

In the current study, we obtained DENV genomes from 318 VCD cases detected in the AWED trial. We used phylogenomic analysis to assign the DENV sequences to six genotypes, 8 lineages and inferred the transmission-relatedness between dengue case pairs based on their spatiotemporal and genomic relationships. We report the prevalence of the different DENV genotypes and their global distribution to identify the geographies that share the same DENV genotypes as Yogyakarta. Further, we show that wMel protection extended to all six genotypes identified amongst AWED trial participants.

Material and methods

Description of the AWED trial

The design, conduct and primary outcomes of the AWED trial have been described previously 16,20. Briefly, enrolled participants were consenting patients presenting to 18 primary care clinics in Yogyakarta City and Bantul District between January 2018 and March 2020 with undifferentiated acute febrile illness of 1–4 days duration and aged between 3 and 45 years, and resident in the 26 km2 trial area in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. The trial area comprised 24 geographical clusters (average 1 km2 in area) that had been randomly allocated 1:1 to receive wMel-infected Ae. aegypti releases (completed between March and December 2017) or no intervention (untreated clusters). In response to local clusters of dengue case notifications, insecticides (fogging) for vector control were applied by environmental health teams in the untreated and treated clusters at similar frequencies (events per month) prior to wMel deployment but thereafter were 83% less frequent in treated areas24.

Of the 6,306 enrolled participants included in the primary analysis, 385 had virologically—confirmed dengue as determined by DENV-specific RT-qPCR and/or NS1-specific ELISA. Of those 385 VCDs, 67 had detectable NS1 antigen but not DENV RNA, and hence their plasma samples were not suitable for sequencing. Genomes were obtained from VCDs resident in both untreated clusters (266/319 total genomes, 83.4%) and treated clusters (53/319, 16.6%). All four DENV serotypes were detected, with DENV-2 and DENV-4 predominant as described previously 25.

Blood sample collection and human ethics

Venous blood samples were collected from participants enrolled into the AWED trial as described previously 16. The AWED trial was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation and was approved by the human research ethics committees at Monash University (approval number 0960) and Universitas Gadjah Mada (approval number KE/FK/105/EC/2016). Written informed consent for participation in the trial was obtained from all participants. The additional analyses performed in this ancillary study to the trial were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) at the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada under study protocol 01062020 version 1.1. The sequencing study was conducted according to the regulations stipulated within the approved protocol.

Viral whole genome sequencing

RNA (5 μl) was extracted from plasma with High pure viral nucleic acid kit (Roche) and reverse transcribed into cDNA with SuperScript IV First-strand synthesis system kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using random hexamer and the following incubation conditions: 23 °C-10 min, 50 °C-45 min, 55 °C-15 min, 80 °C-10 min. In two separate PCR reactions containing primer pools that spanned the whole DENV genome, viral cDNA was amplified according to conditions previously described 26,27,28. Amplicons were purified with AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) and the two amplicon pools were combined per sample at similar concentrations (0.4 ng/μl). This formed the input DNA for library construction using Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) and IDT for Illumina UD Indexes (Sets A-D). Indexed samples were quantified with KAPA Library Quantification kit (Roche) and then normalised by dilution to 10 nM, prior to pooling all samples into the library. Sequencing of the library was performed by MHTP Medical Genomics Facility at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research with a P2 v3 300-cycle kit on NextSeq2000 machines. Bioinformatic pipelines were executed in Snakemake (v5.3.0) 29. Adapter and primer sequences, short reads (length < 50 bases) and low-quality bases (quality score < 30) were removed from sequencing reads with AlienTrimmer (v0.4.2) 30. Cleaned reads were aligned to DENV reference genomes (GenBank accession numbers KY053732, EF051521, MN018389 and KC762696) with BWA-MEM (v0.7.17). Consensus sequences were called with iVar (v1.3.1) using default parameters 26. Read and alignment quality were evaluated with QualiMap (v2.2.2) and MultiQC (v1.11) 31,32. In instances of < 10 × coverage, the portion of the genome was imputed from the consensus sequence of the relevant DENV genotype. Imputed regions and other quality control metrics of the sequencing analysis are shown per sample in Supplementary Table 1. Consensus sequences are accessible through GenBank (accession numbers PP151905–PP152223).

Phylogenetic analyses

Genotype and lineage assignment

Global DENV whole-genome sequence sets that represent a well-defined and diverse set of full-length DENV genomes (4118 sequences) Fonseca et al. 33 were downloaded from GenBank. Global and Yogyakarta DENV nucleotide sequences were aligned with MAFFT (v7.450) and maximum likelihood (ML) trees were inferred with IQ-TREE (v2) with 1000 replicates. Genotypes were assigned by examining the consensus tree (Supplementary Fig. 1) for the relatedness of Yogyakarta sequences to reference whole-genome DENV sequences 33. Whole DENV genomes were assigned to lineages according to a standardised lineage classification system 34. Phylogenetic trees were viewed with ggtree (v3.4.1) in RStudio (v2022.07.0).

Genomic cluster assignment

DENV sequences were grouped below the hierarchical level of genotype by genetic distance (gD) thresholds and > 95% support of bootstrapped branch lengths with Cluster Picker v1.2 35. Genomic clusters (monophyletic clades) were defined by a gD threshold of ≤ 0.5%.

Phylogeography

Dengue E sequence datasets were used and included representative sequences from Yogyakarta AWED trial participants in addition to E sequences deposited in GenBank. GenBank sequences were filtered and included sequences originating from countries in Asia and Oceania collected between 2000 and 2020. Datasets were used to produce large ML phylogenetic trees. These were rarefied to 200 sequences per serotype with Treemmer (version 3.9.1) to form a more manageable dataset for Bayesian phylogeographic analyses. To reconstruct the phylogeographic history a discrete Bayesian analysis was conducted in Beast. Briefly, this used the HKY substitution model, an uncorrelated relaxed molecular clock and a coalescent exponential growth tree prior. Approximately 200,000,000 MCMC chains with a sampling frequency of 10,000 and 10% burnin yielded ESS values of > 100 for each DENV serotype.

Genotype distribution

To describe the recent geographic footprint of the DENV genotypes that were prevalent in Yogyakarta, and therefore to predict where the wMel intervention might have a similar impact, we downloaded global DENV sequences (> 100 bp in length) deposited in GenBank with collection dates between 2015 and 2020 and assigned a genotype in Genome Detective based on bootstrap support ≥ 90. Of 14,251 DENV sequences downloaded from GenBank, genotype was only assigned to the 1770 sequences that had strong phylogenetic support. Genotype distributions were plotted with ggplot2 in RStudio.

Genotype-specific efficacy of wMel mosquito releases

The protective efficacy of wMel mosquito releases was estimated for each of the two DENV-1 and two DENV-4 genotypes detected in the AWED trial using the same methods as the intention-to-treat and serotype-specific efficacy estimates reported previously 16. Briefly, the odds of residence in a wMel-treated cluster among participants with VCD caused by each genotype was compared with the odds among test-negative controls, to calculate an aggregate odds ratio and permutation-based confidence interval. Efficacy was calculated as 100 x (1-aggregate odds ratio). Efficacy was not estimated for DENV-2 Cosmopolitan genotype or DENV-3 genotype I, since these were the only genotypes detected for these two serotypes.

Spatiotemporal analysis of DENV genomic clusters

Dengue transmission dynamics in wMel-intervention versus untreated areas of Yogyakarta were inferred by grouping DENV sequences into genomic clusters (monophyletic clades) defined by a genetic distance (gD) threshold of ≤ 0.5% and strong phylogenetic support (bootstrapping values ≥ 95). To characterise the fine scale spatial and temporal structure of the DENV genomic diversity identified in Yogyakarta, we evaluated pairwise each VCD case from which a DENV sequence was isolated against every other VCD case in terms of the spatial distance (in metres) between their locations of residence and the temporal interval (in days) between illness onset date. The proportion of case pairs belonging to the same genomic cluster was calculated overall, and for binned categories of the spatial and temporal distance between cases, at non-overlapping spatial intervals of 100 m up to 1000 m, and temporal intervals of 0–1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–6, 6–12, and > 12 months. Data processing and descriptive analysis was performed in StataSE v16 and graphing in GraphPad Prism v9.3.1.

Results

DENV genomic diversity in Yogyakarta in 2018–2020

Plasma samples from the 318 PCR-positive VCD cases detected in the AWED trial yielded 319 DENV genome sequences from 317 individuals: no sequence was obtained from one individual due to an absence of index-assigned sequencing reads. Among six individuals with DENV serotype co-infections detected by PCR, sequences were obtained for both infecting DENV serotypes for two individuals, and for only one serotype in the other four individuals. Read mapping and coverage metrics are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

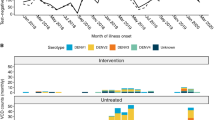

As previously described, all four DENV serotypes were detected during the 27-month trial period with the majority of VCD cases attributable to DENV-2 and DENV-4 16,25. Inspection of DENV genome sequences demonstrated the DENV-1 and DENV-4 populations each contained two genotypes that co-circulated temporally (Fig. 1, Table 1). DENV-1 genotype I (major lineage K, N = 40; 12.5% of total sequenced DENV) and DENV-4 genotype II (major lineage A, N = 82; 25.7%) were more prevalent than DENV-1 genotype IV (major lineage C, N = 15; 4.7%) and DENV-4 genotype I (major lineage A, N = 5; 1.6%), respectively. In contrast, the DENV-2 population consisted of a single Cosmopolitan genotype (N = 150; 47%) comprised of three major virus lineages (lineage F, N = 87; 27.3%, lineage D, N = 56; 17.6% and lineage C, N = 7; 2.2%) whilst the DENV-3 population comprised only genotype I (major lineage A, N = 27; 8.5%) viruses.

Phylogeographical inferences reveal that DENV lineages were endemic to Indonesia or Yogyakarta. Their endemicity dates back to a minimum of four years before the AWED trial began (Supplementary Fig. 2). DENV-4 genotype I was the only example of a recently introduced DENV into Yogyakarta, which originated from Thailand but was imported to Indonesia in 2016 (95% credible interval = 2014–2016), and first detected in Yogyakarta in 2019.

Geographical distribution of DENV genotypes identified in Yogyakarta

The geographical distribution of 1770 DENV sequences included E, NS1 and full-genome sequences sampled from countries between 2015 and 2020 and is shown in Fig. 2. The total number of DENV sequences included per country is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. DENV-1 genotype I was broadly distributed across countries in Asia including China, Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, India, Laos, Indonesia, Cambodia and New Caledonia (Fig. 2). DENV-1 genotype IV was common in the Philippines, China and French Polynesia but was rarely found in Indonesia. This is consistent with fewer DENV-1 genotype IV than genotype I sequences (N = 15 vs N = 40) being detected during the AWED trial, and the observation by others that genotype I has been the dominant DENV-1 genotype in Indonesia since 2015 following a decade of cocirculation with genotype IV 9. DENV-2 Cosmopolitan and DENV-4 genotype II were widely distributed throughout America, Asia and Oceania. DENV-3 genotype I prevalence was more focal, being found in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Myanmar and China. DENV-4 genotype I was not found in Indonesia prior to its detection in five AWED trial participants, but was prevalent in other Asian countries: Thailand, India, Vietnam, Myanmar and China. Collectively, these data demonstrate that the DENV genotypes detected in Yogyakarta in 2018–2020 are representative of the genotypes circulating elsewhere in the Asia–Pacific region during the same period.

Global distribution of DENV genotypes detected in Yogyakarta. The number of DENV sequences retrieved from GenBank per country of collection during the years 2015–2020 with an assigned genotype are shown. Global maps (one for each genotype) were rendered with ggplot2 in RStudio. The number of DENV sequences is depicted on a continuous scale, which differs per genotype depending on the maximum number of assigned sequences.

DENV genotype-specific efficacy of wMel-infected mosquito releases

The primary intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis of the AWED trial 16 demonstrated the efficacy of wMel releases in reducing VCD incidence overall and for each of the four DENV serotypes. Here, we show further that wMel efficacy was equivalent (within ± 10% of serotype-specific efficacy point estimates) for the individual genotypes within DENV serotypes 1 and 4 (Fig. 3). Point estimates for DENV-1 genotype IV and DENV-4 genotype I should be interpreted conservatively as the low frequency of these genotypes prevented calculation of confidence intervals. Overall, analysis at the level of genotype indicates that the wMel intervention effect is not only pan-serotypic but extends to all six-DENV genotypes detected in the AWED trial.

Genotype-specific efficacy of wMel. The protective efficacy was calculated as 100x (1-aggregate odds ratio), overall and by serotype as reported previously 16, and by genotype. Circles indicate point estimates and lines the 95% confidence interval. *Genotypes with too few observations to generate meaningful confidence intervals. ^DENV-1 and DENV-2 genotype-specific VCDs sum to fewer than the serotype totals because sequencing quality and coverage did not permit genotype assignment for all cases, particularly in instances of coinfection.

Genomic clustering among dengue cases in the AWED trial

Genomes obtained from VCDs were clustered by phylogenomic similarity (genetic distance ≤ 0.5%) and the spatiotemporal relationships among genomically clustered VCDs, resident in untreated and treated areas, were analysed. The genomic clusters represent monophyletic clades of sequences that share a very recent common ancestor suggestive of linkage to a common transmission chain.

Among the 319 DENV sequences, 289 (91%) were grouped with at least one other sequence in a genomic cluster. The proportion of unclustered sequences was similar among VCD cases resident in wMel-intervention versus untreated areas (6/53: 11% vs 24/266: 9%, respectively). A total of 48 genomic clusters were identified, with a median of 4 members (range 2–55; interquartile range 2–6); see Supplementary Table 2. Twenty of these 48 genomic clusters consisted exclusively of DENV sequences from VCD cases resident in untreated areas. Strikingly, no genomic clusters consisted only of DENV sequences from VCD cases resident in wMel-intervention areas. Of the remaining 28 genomic clusters, 9 included only a single DENV derived from a case resident in a wMel-intervention area. The persistence of the genomic clusters over time was highly variable, with 19/48 clusters persisting across sequential dengue seasons and 29/48 detected only within a single season (Fig. 4).

Timeline of DENV genomic clusters. Markers represent virologically-confirmed dengue cases (n = 289) detected during the AWED trial in Yogyakarta with a DENV sequence belonging to one of 48 identified genomic clusters. Cases are plotted by illness onset date (X axis) and genomic cluster grouped by DENV serotype (Y axis). Open circles indicate the cases resident in the untreated arm of the AWED trial (n = 242) and closed triangles the cases resident in the wMel-treated arm (n = 47). Horizontal lines connect the illness onset dates of the first and last VCD within each genomic cluster, to show cluster duration (solid line: clusters persisting across sequential dengue seasons; dotted line: clusters detected only within a single season).

DENV genomic clustering was strongly positively associated with both the spatial and temporal proximity between dengue case pairs consistent with the known focal transmission of dengue. Among all dengue case pairs with illness onset within 1 month of each other, regardless of serotype, 75% (95% CI: 66–82%) of those resident within 100 m of each other belonged to the same genomic cluster (Fig. 5). This decreased to 24% (95% CI: 17–33%) for cases resident 400–500 m apart and 6% (95% CI: 5.1–6.1%) for those ≥ 1 km apart. A temporal dependence was also observed, for case pairs up to 3 months and 400 m apart (Fig. 5). The association between genomic clustering and spatial proximity was lost for case pairs separated by > 3 months (Fig. 5; Supplementary Tables 3, 4 and 5).

DENV genomic clustering is spatially and temporally dependent. Proportion of all dengue case pairs, regardless of serotype, that belong to the same genomic cluster, stratified by their temporal proximity (time between illness onset: up to 1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–6, 6–12, or > 12 months) and spatial proximity (distance between primary residence: non-overlapping bins of 100 m up to 500 m, then 500–1000 m or > 1000 m. Bins are labelled at their upper bound). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The horizontal dotted line represents the overall proportion of dengue case pairs that belong to the same genomic cluster, regardless of spatial or temporal proximity.

This observed spatial and temporal structure to DENV evolutionary relationships predominantly reflects dengue transmission dynamics in the untreated areas of Yogyakarta, and is largely interrupted by the wMel intervention. Among 1378 unique case pairs where both cases resided in a Wolbachia-treated area, there were only two where the cases shared the same genomic cluster and occurred within a spatial and temporal proximity consistent with potential transmission-relatedness (300 m and 3 months) (Supplementary Tables 3, 4 and 5).

Discussion

Following on from the AWED RCT of Wolbachia (wMel-strain) mosquito releases in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, we resolved the DENV genotypes carried by 318 VCDs resident across intervention and untreated areas and found that wMel provided multi-genotype protective efficacy against dengue. The protective efficacy of wMel-infected Ae. aegypti releases in Yogyakarta was comparable for all six DENV genotypes identified during the AWED trial, extending the pan-serotypic efficacy reported previously 16. Of the six DENV genotypes identified, five were endemic to Indonesia 9,12 and one, DENV-4 genotype I, was identified only once prior in Indonesia, Bali in 2015 5. Infrequent prior detection of DENV-4 genotype I might indicate non-endemicity or signal undersampling in genomic surveillance. DENV-1 genotype IV and DENV-4 genotype I were detected at too low a frequency to calculate the precision of the efficacy estimates. Although the point estimates for these genotypes fell within the 95% confidence intervals for the respective serotype-level efficacy, this result should be carefully re-evaluated in the future to determine whether wMel protective efficacy observed in the AWED trial is comparable in other geographic settings where these virus genotypes circulate.

Of the six genotypes detected, four (DENV-1 genotypes I and IV, DENV-3 genotype I and DENV-4 genotype I) have been primarily sampled previously in endemic countries within the Asia–Pacific 36,37,38,39,40,41,42. DENV-2 Cosmopolitan has been repeatedly sampled in the Asia–Pacific, the Middle East and Africa over the last 30 years 43,44,45. Its geographical range has expanded in recent years: in 2019 it was sampled in dengue outbreaks for the first time in South America 43,46,47. DENV-4 genotype II is also globally distributed; and prevalent in Asia and South America 48. These published genotype distributions are mostly consistent with the per-genotype distributions reported in our geographical mapping analysis, although some limitations in our analysis might have overrepresented imported infections and dengue burden for countries with well-resourced diagnostic and sequencing capability.

Different genotypes from those found in Yogyakarta have been sampled recently elsewhere in Asia and South America, including DENV-1 (genotypes III and V), DENV-2 (Asian I, Asian II and Asian American genotypes) and DENV-3 (genotypes I, II and III) 49,50,51,52,53. Some of these genotypes have been tested in laboratory vector competence assays with wMel-infected Ae. aegypti and there is no evidence of individual DENV genotypes evading wMel-induced virus blocking 21,22. Reproducible evidence of the epidemiological impact of wMel deployments from non-randomised field trials in different geographical settings in the Asia–Pacific14,15 and Latin America 17,19 provides further support for a generalised wMel protective effect across the diversity of DENV genotypes. Although the specific DENV genotypes circulating in the Colombian 19 and Brazilian 17 wMel intervention areas have not been determined, recent surveillance in Medellín (Colombia) and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) suggests hyperendemicity, with co-circulation of DENV-1 genotype V, DENV-3 genotype III, DENV-2 Asian American and Cosmopolitan genotypes 54,55,56,57,58. The evidence for sustained interruption of dengue outbreaks in these Latin American intervention areas 17,19 suggests no individual DENV genotype risks breakthrough transmission following wMel establishment.

Our results extend previous serotype-level analyses of the spatial–temporal clustering of dengue cases in Yogyakarta 25 by further characterising the spatial and temporal structure underlying the DENV phylogenetic relationships at the level of monophyletic clade. We show that DENV phylodynamics in Yogyakarta were defined by strong spatial and temporal signals, with three quarters of dengue cases that lived within 100 m of each other (and had onset within 1 month) belonging to the same DENV monophyletic clade, compared with only six percent of cases separated by > 500 m. This strong relationship between the spatial, temporal and genetic proximity of dengue cases is consistent with the large majority of transmission occurring around the home. A spatial structure to DENV genomic relationships has been reported previously in Bangkok 59, with spatial dependence persisting to distances of 2 km or greater. In Yogyakarta the spatial structure was lost by 500 m, reflecting the presence of Wolbachia in 12 of 24 clusters, each on average 1km2 in size, disrupting the spatial structure of DENV transmission beyond the boundaries of the untreated clusters. Additional factors to Wolbachia such as population size and structure, human mobility and immune status of the population might also contribute to differing spatiotemporal clustering patterns between Yogyakarta and other cities in urban areas.

Consistent with previous evidence of the near-total elimination of DENV transmission in Wolbachia-treated areas of Yogyakarta 25, sequencing revealed only two pairs of genetically-linked VCD cases resident in Wolbachia-treated areas (up to 300 m apart) and with onset within 3 months of each other, within the whole 27-month case surveillance period. Although we cannot exclude or quantify the possibility that focal DENV transmission within Wolbachia-treated areas led to asymptomatic DENV infections or VCDs that were not detected in the AWED trial, this imperfect sensitivity applies equally to the untreated areas, and our findings suggest that the majority of cases resident in intervention clusters will have acquired their infection in an untreated location away from home. Previous descriptive analyses of the travel histories collected from all participants in the AWED trial at enrolment, for the period 3–10 days prior to illness onset, showed that only 60% (192/318) of VCD cases resident in untreated areas and 49% (33/67) of VCD cases resident in Wolbachia-treated areas reported spending all of that exposure period at locations with a Wolbachia intervention status concordant with their home 60. We explored the integration of these travel histories with the DENV genomic data in the current study, to consider also non-home locations in the spatial relationships between genomically clustered cases. However, the large additional ‘background noise’ introduced by considering multiple spatial relationships between each case pair, together with the very strong spatial clustering signal based on residential location, meant no direct inference could be made on the contribution of non-home locations to transmission.

Is there a role for DENV genomic surveillance in evaluating the real-world effectiveness of Wolbachia introgression and monitoring for virus resistance? Genomic surveillance could conceivably be used to complement routine public health investigations into any dengue case clusters detected after area-wide Wolbachia establishment. This has not been necessary in Cairns, Australia as breakthrough infections have not been detected since wMel establishment more than 10 years ago, despite repeated importation of dengue cases from overseas 61. The rate of DENV importation, and potentially also the diversity of imported lineages, is likely to be much higher in Yogyakarta, however. Plausibly, if dengue cases without a documented travel history outside of Yogyakarta occur, genomic epidemiology could be a useful tool to inform an assessment of whether the cases represent local “breakthrough” transmission, and to identify whether any particular serotypes or genotypes are consistently associated with such transmission. Despite the importance of genomic surveillance, the time, cost and speciality expertise required to generate and analyse DENV genomes is likely to preclude its use in most dengue-endemic settings.

In conclusion, wMel introgression affords broad protection against DENV genotypes that are either prevalent in Asia or globally distributed. Viral surveillance in other Wolbachia release sites worldwide, prior to and after Wolbachia establishment, can further enhance understanding of the extent of wMel protection against diverse DENV lineages as well as other viruses transmitted by Ae. aegypti.

Data availability

All data generated in or analysed as part of the current study are included in this published article and its supplementary information. Dengue virus genomes are available via GenBank under accession numbers PP151905–PP152223.

References

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study (2019). 2019 Preprint at https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

O’Reilly, K. M. et al. Estimating the burden of dengue and the impact of release of wMel Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes in Indonesia: A modelling study. BMC Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1396-4 (2019).

Prayitno, A. et al. Dengue seroprevalence and force of primary infection in a representative population of urban dwelling Indonesian children. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005621 (2017).

Stanaway, J. D. et al. The global burden of dengue: An analysis from the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 712–723 (2016).

Utama, I. M. S. et al. Dengue viral infection in Indonesia: Epidemiology, diagnostic challenges, and mutations from an observational cohort study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007785 (2019).

Harapan, H., Michie, A., Mudatsir, M., Sasmono, R. T. & Imrie, A. Epidemiology of dengue hemorrhagic fever in Indonesia: Analysis of five decades data from the National Disease Surveillance. BMC Res. Notes 12, 350 (2019).

Holmes, E. & Twiddy, S. The origin, emergence and evolutionary genetics of dengue virus. Infect., Genet. Evol. 3, 19–28 (2003).

Rico-Hesse, R. Microevolution and virulence of dengue viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 59, 315–341 (2003).

Harapan, H. et al. Dengue viruses circulating in Indonesia: A systematic review and phylogenetic analysis of data from five decades. Rev. Med. Virol. 29(4), e2037. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2037 (2019).

Gubler, D. J. et al. Virological surveillance for dengue haemorrhagic fever in Indonesia using the mosquito inoculation technique. Bull. World Health Organ. 57, 931–936 (1979).

Indriani, C. et al. Baseline characterization of dengue epidemiology in Yogyakarta City, Indonesia, before a randomized controlled trial of Wolbachia for arboviral disease control. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 99, 1299–1307 (2018).

Arguni, E. et al. Dengue virus population genetics in Yogyakarta, Indonesia prior to city-wide Wolbachia deployment. Infect., Genet. Evol. 102, 105308 (2022).

O’Neill, S. L. et al. Scaled deployment of Wolbachia to protect the community from dengue and other Aedes transmitted arboviruses. Gates Open Res. 2, 36 (2018).

Ryan, P. A. et al. Establishment of wMel Wolbachia in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and reduction of local dengue transmission in Cairns and surrounding locations in Northern Queensland Australia. Gates Open Res. 3, 1547 (2019).

Indriani, C. et al. Reduced dengue incidence following deployments of Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: A quasi-experimental trial using controlled interrupted time series analysis. Gates Open Res. 4, 50 (2020).

Utarini, A. et al. Efficacy of Wolbachia-infected mosquito deployments for the control of dengue. New Engl. J. Med. 384, 2177–2186 (2021).

Pinto, S. B. et al. Effectiveness of Wolbachia-infected mosquito deployments in reducing the incidence of dengue and other Aedes-borne diseases in Niterói, Brazil: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15, e0009556 (2021).

Gesto, J. S. M. et al. Large-scale deployment and establishment of Wolbachia into the Aedes aegypti population in Rio de Janeiro Brazil. Front. Microbiol. 12, 2113 (2021).

Velez, I. D. et al. Reduced dengue incidence following city-wide wMel Wolbachia mosquito releases throughout three Colombian cities: Interrupted time series analysis and a prospective case-control study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17(11), e0011713 (2023).

Anders, K. L. et al. The AWED trial (Applying Wolbachia to Eliminate Dengue) to assess the efficacy of Wolbachia-infected mosquito deployments to reduce dengue incidence in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 19, 302 (2018).

Carrington, L. B. et al. Field- and clinically derived estimates of Wolbachia -mediated blocking of dengue virus transmission potential in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Proceed. Nat. Acad. Sci. 115, 361–366 (2018).

Flores, H. A. et al. Multiple Wolbachia strains provide comparative levels of protection against dengue virus infection in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008433 (2020).

Ye, Y. H. et al. Wolbachia reduces the transmission potential of dengue-infected Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003894 (2015).

Indriani, C. et al. Impact of randomised wMel Wolbachia deployments on notified dengue cases and insecticide fogging for dengue control in Yogyakarta city. Glob. Health Action 16(1), 2166650 (2023).

Dufault, S. M. et al. Disruption of spatiotemporal clustering in dengue cases by wMel Wolbachia in Yogyakarta Indonesia. Sci. Rep. 12, 9890 (2022).

Grubaugh, N. D. et al. An amplicon-based sequencing framework for accurately measuring intrahost virus diversity using PrimalSeq and iVar. Genome Biol. 20, 8 (2019).

Quick, J. et al. Multiplex PCR method for MinION and Illumina sequencing of Zika and other virus genomes directly from clinical samples. Nat. Protoc. 12, 1261–1276 (2017).

Vi, T. T. et al. A serotype-specific and tiled amplicon multiplex PCR method for whole genome sequencing of dengue virus. J. Virol. Methods 328, 114968 (2024).

Felix, M. et al. Sustainable data analysis with snakemake. F1000Research. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.29032.2 (2021).

Criscuolo, A. & Brisse, S. AlienTrimmer: A tool to quickly and accurately trim off multiple short contaminant sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. Genomics 102, 500–506 (2013).

García-Alcalde, F. et al. Qualimap: Evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics 28, 2678–2679 (2012).

Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016).

Fonseca, V. et al. A computational method for the identification of Dengue, Zika and Chikungunya virus species and genotypes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13, e0007231 (2019).

Hill, V. et al. A new lineage nomenclature to aid genomic surveillance of dengue virus. PLoS Biol. 22(9), e3002834. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.16.24307504 (2024).

Ragonnet-Cronin, M. et al. Automated analysis of phylogenetic clusters. BMC Bioinform. 14, 317 (2013).

Takemura, T. et al. The 2017 Dengue virus 1 outbreak in northern Vietnam was caused by a locally circulating virus group. Trop. Med. Health 50, 3 (2022).

Tun, M. M. et al. Characterization of the 2013 dengue epidemic in Myanmar with dengue virus 1 as the dominant serotype. Infect., Gen. Evol. 43, 31–37 (2016).

Atchareeya, A. et al. Sustained transmission of dengue virus type 1 in the Pacific due to repeated introductions of different Asian strains. Virology 329(2), 505–512 (2004).

Dupont-Rouzeyrol, M. et al. Epidemiological and molecular features of dengue virus type-1 in New Caledonia, South Pacific, 2001–2013. Virol J 11, 61 (2014).

Soe, A. M. et al. Emergence of a novel dengue virus 3 (DENV-3) genotype-I coincident with increased DENV-3 cases in Yangon, Myanmar between 2017 and 2019. Viruses 13, 1152 (2021).

Inizan, C. et al. Dengue in new Caledonia: Knowledge and gaps. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 4, 95 (2019).

Yoksan, S. et al. Molecular epidemiology of dengue viruses isolated from patients with suspected dengue fever in Bangkok, Thailand during 2006–2015. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 49, 604 (2018).

Yenamandra, S. P. et al. Evolution, heterogeneity and global dispersal of cosmopolitan genotype of Dengue virus type 2. Sci. Rep. 11, 13496 (2021).

Selhorst, P. et al. Phylogeographic analysis of dengue virus serotype 1 and cosmopolitan serotype 2 in Africa. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 133, 46–52 (2023).

Zaki, A., Perera, D., Jahan, S. S. & Cardosa, M. J. Phylogeny of dengue viruses circulating in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: 1994–2006. Trop. Med. Int. Health 13, 584–592 (2008).

Giovanetti, M. et al. Emergence of dengue virus serotype 2 cosmopolitan genotype Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 28, 1725–1727 (2022).

García, M. P., Padilla, C., Figueroa, D., Manrique, C. & Cabezas, C. Emergence of the Cosmopolitan genotype of dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV2) in Madre de Dios, Peru, 2019. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud. Publica. 39, 126–128 (2022).

AbuBakar, S., Wong, P.-F. & Chan, Y.-F. Emergence of dengue virus type 4 genotype IIA in Malaysia. J. Gen. Virol. 83, 2437–2442 (2002).

Jagtap, S., Pattabiraman, C., Sankaradoss, A., Krishna, S. & Roy, R. Evolutionary dynamics of dengue virus in India. PLoS Pathog. 19, e1010862 (2023).

Rabaa, M. A. et al. Genetic epidemiology of dengue viruses in phase III trials of the CYD tetravalent dengue vaccine and implications for efficacy. Elife 6, e24196 (2017).

Ramos-Castañeda, J. et al. Dengue in Latin America: Systematic review of molecular epidemiological trends. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005224 (2017).

Naveca, F. G. et al. Reemergence of dengue virus serotype 3, Brazil, 2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis 29, 1482–1484 (2023).

Maduranga, S. et al. Genomic surveillance of recent dengue outbreaks in Colombo Sri Lanka. Viruses 15, 1408 (2023).

Lim, J. K. et al. Epidemiology and genetic diversity of circulating dengue viruses in Medellin, Colombia: A fever surveillance study. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 1–6 (2020).

Gräf, T. et al. Multiple introductions and country-wide spread of DENV-2 genotype II (Cosmopolitan) in Brazil. Virus Evol. 9, 1–4 (2023).

Gularte, J. S. et al. DENV-1 genotype V linked to the 2022 dengue epidemic in Southern Brazil. J. Clin. Virol. 168, 105599 (2023).

Mendes, M. A. et al. Dengue virus serotype 2 genotype III evolution during the 2019 outbreak in Mato Grosso Midwestern Brazil. Gen. Evol. 113, 105487 (2023).

de Bruycker-Nogueira, F. et al. DENV-1 Genotype V in Brazil: Spatiotemporal dispersion pattern reveals continuous co-circulation of distinct lineages until 2016. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 17160 (2018).

Salje, H. et al. Dengue diversity across spatial and temporal scales: Local structure and the effect of host population size. Science 355, 1302–1306 (2017).

Dufault, S. M. et al. Reanalysis of cluster randomised trial data to account for exposure misclassification using a per-protocol and complier-restricted approach. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 11207. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.20.23288835 (2024).

Ritchie, S. A. Wolbachia and the near cessation of dengue outbreaks in Northern Australia despite continued dengue importations via travellers. J. Travel Med. 25(1), tay84. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tay084 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of the AWED Study Group members for trial implementation. We thank the Tahija Foundation for funding the trial, and the Wellcome Trust and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for financial support to the World Mosquito Program. We also acknowledge Kien Duong for providing the dengue-specific primer sets used to amplify virus genomes.

Funding

Funding was provided by National Health and Medical Research Council (Grant nos. 1173928, 1173928) World Mosquito Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS, KA and KE wrote the main manuscript text. CS, KA, KE, ES, EA, CI, SD, RAA, RTS and JD contributed to data collection, analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Edenborough, K., Supriyati, E., Dufault, S. et al. Dengue virus genomic surveillance in the applying Wolbachia to eliminate dengue trial reveals genotypic efficacy and disruption of focal transmission. Sci Rep 14, 28004 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78008-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78008-y