Abstract

Various aspects of the new development of organic-inorganic hybrid [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 single crystals have been discussed. The phase transition temperatures were determined to be 268 K (TC2) and 291 K (TC1), and the thermodynamic stability was maintained at temperatures up to 669 K. The crystal structures at 250 K (phase III), 275 K (phase II), and 300 K (phase I) are monoclinic, orthorhombic, and orthorhombic, respectively. Notably, while the 1H and 13C chemical shifts gradually changed near TC1 and TC2, the 14N resonance frequency exhibited a split in the number of signals near TC1. Furthermore, the shorter spin-lattice relaxation time T1ρ of 1H than that of 13C suggests facile energy transfer for1H. Additionally, analysing the temperature dependencies of T1ρ for 13C revealed that the activation energy Ea in phase I is approximately five times greater than those in phases III and II. The high Ea observed in phase I primarily stems from the collective motion of the N(CH3)4 group, which contrasts with the considerable freedom observed for the CH3 group in phases III and II. These distinctive physical properties suggest potential applications for [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 as an organic‒inorganic hybrid material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Metal‒organic hybrids, which consist of organic and inorganic compounds1,2,3,4,5,6,7, have recently attracted significant attention because these materials have many possibilities for tailoring their functionalities and physical properties, including optical, electrical, and magnetic properties8. Hybrid organic‒inorganic compounds based on perovskite A2BX4structures are an interesting class of materials9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Examples of such materials include methylammonium lead halides, which can be used in perovskite solar cells, light-emitting diodes, lasers, and photodetectors22. These crystals have been the subject of numerous scientific investigations over a long period of time and have attracted particular attention from researchers owing to their complicated sequence of structural phase transitions. [N(CH3)4]2BX4 crystals belong to a large group of materials whose general chemical formula can be written as A2BX4, where A = K, Rb, Cs, NH4, N(CH3)4; B = Mn, Co, Cu, Zn, Cd; and X= I, Cl, Br23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. In particular, the appearance of successive lattice transformations from a prototype structure to an incommensurate structure to a commensurate structure was a relatively new phenomenon in the investigation of phase transitions.

Over the years, [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4crystals, bis(tetramethylammonium) tetra-chloromanganate (II), have been the subject of numerous scientific investigations31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49. [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4single crystals exhibit three phase transitions with decreasing temperatures of 290, 266.5, and 175 K50. After that, an intermediate incommensurate phase exists between 292.1 and 291.5 K, as reported by Mashiyama and Tanisaki39. Hereafter, Phase I − 292.1 K − Phase II (Incommensurate) − 291.5 K − Phase III − 266.5 K − Phase IV − 175 K − Phase V. Phase I is orthorhombic, with the space group Pmcn and the parameters a = 9.070 Å, b = 15.636 Å, c = 12.345 Å, and Z = 4.34.36 The basic structure comprises three tetrahedral molecules: MnCl42− and two types of disordered N(CH3)4(1) and N(CH3)4(2). Phase II is incommensurate and occurs over a very narrow temperature interval. Phase III is monoclinic, with the space group P21/c and the parameters a = 9.041 Å, b = 15.626 Å, c = 24.661 Å, α = 89.96°, and Z = 8.36 The MnCl4 tetrahedra alternate between two configurations from phase I. Polarizing microscopic observations reveal monoclinic domains with ferroelastic properties on the a-plate sample. Phase IV is also monoclinic, with the space group P21/n and the parameters a = 9.037 Å, b = 15.589 Å, c = 36.973 Å, γ = 90.22°, and Z = 12.36 The threefold superstructure is characterized by the alternate rotation of the MnCl4 tetrahedra about an axis parallel to the c-axis. Additionally, monoclinic domains with ferroelastic properties in phase IV were observed on the c-plate. Phase V is monoclinic, with the space group P21/c and the parameters a = 8.977 Å, b = 15.334 Å, c = 12.216 Å, β = 90.16°, and Z = 4.36 Each MnCl4 and N(CH3)4 tetrahedron rotates about an axis parallel to the b-axis, as well as about the c-axis. A summary of phase transition temperatures for [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 crystal previously reported is provided in Scheme 1, where the crystal structure and space group are presented for each phase. The phase transition temperatures vary among different research groups, highlighting the need for more comprehensive studies on the physical properties.

Previous studies on [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4have extensively explored its optical properties40,41,42, and the phase diagram under hydrostatic pressure has been under consideration for many years44,45,46,47,48,49. Despite the numerous experimental findings reported for [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4, the structural geometry and molecular motion associated with the phase transitions have remained undisclosed.

In this study, the structure and lattice constant of the perovskite [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 single crystal grown here were determined at phases I, II, and III through single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) experiments. To elucidate the influence of [N(CH3)4] ions near phases I, II, and III in the [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 single crystal, we conducted measurements on the temperature dependencies of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) chemical shifts for 1H and 13C, as well as the static NMR resonance frequency for 14N. Additionally, we considered energy transfer through the NMR spin-lattice relaxation time T1ρ and discussed changes in the activation energy (Ea) related to the roles of CH3 and [N(CH3)4]. In studying the phase transition behaviour, NMR results are a valuable tool for obtaining dynamic information about the phase transitions.

Methods

Crystal growth

Single crystals of [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 exhibiting excellent optical quality were grown via a slow evaporation process from supersaturated solutions by dissolving N(CH3)4Cl (Aldrich, 98%) and MnCl2 (Aldrich, 99.9%) in distilled water with molecular weight of 2:1. The solution was stirred and heated to generate a saturated state. After filtration, the resulting solution yielded single crystals characterized by a yellow hue and high transparency, which were nurtured over several weeks through gradual evaporation in a thermostat maintained at 300 K. The crystals manifested rectangular forms measuring 3 × 3 × 1 mm³. To mitigate degradation due to atmospheric moisture, the crystals were stored in a desiccator.

Characterization

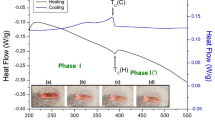

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves were obtained via a DSC instrument (TA Instruments, Model 25) with a heating and cooling rate of 10 °C/min within the temperature range of 200–570 K under a flow of dry nitrogen gas. The morphology of the crystals and melting phenomena were observed via an optical polarizing microscope while monitoring temperature changes. Additionally, a thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve was acquired at a heating rate of 10 °C/min within the temperature range of 300–973 K under a nitrogen gas atmosphere.

The structure and lattice parameters at 250, 275 and 300 K were determined through single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) experiments conducted at the Korea Basic Science Institute (KBSI) Seoul Western Centre. The crystal was mounted on a Bruker SMART CCD diffractometer equipped with graphite-monochromated Mo-Kα radiation and a nitrogen cold stream (-50 °C). Data collection and integration were performed via SMART APEX3 and SAINT software. Absorption corrections were applied via the multiscan method implemented in SADABS. The structure was solved via direct methods and refined via full-matrix least squares on F2 using SHELXTL51. All nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, and hydrogen atoms were placed at their geometrically ideal positions.

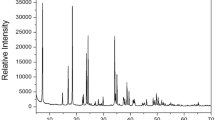

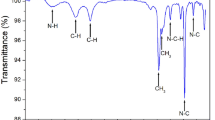

Solid-state NMR spectra of the [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 crystal were acquired using a solid-state NMR spectrometer (Bruker 400 MHz Avance II+) under a magnetic field of 9.4 T at the same facility, KBSI. The 1H magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR resonant frequency of ωo/2π = 400.13 MHz and the 13C MAS NMR resonant frequency of ωo/2π = 100.61 MHz were measured as functions of temperature. Powdered samples were placed into a 4-mm CP/MAS probe. To minimize spinning sidebands, MAS speeds of 5 and 10 kHz were utilized. The 1H and 13C chemical shifts were referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS) standards. One-dimensional (1D) NMR spectra of 1H and 13C were obtained with a delay time of 0.1 s. The 1H and 13C spin-lattice relaxation time T1ρ values were measured with delay times ranging from 200 µs to 100 ms, and 90° pulses for 1H and 13C were set to 3.4 and 4 µs, respectively. Furthermore, the static 14N NMR resonance frequency at a Larmor frequency of 28.90 MHz was recorded with increasing temperature. The 14N NMR resonance frequency was referenced using NH4NO3 as a standard sample, and 14N NMR spectra were acquired via a one-pulse method. 1D NMR spectra of 14N were obtained with a delay time of 0.1 s, and 90° pulses were set to 3 µs. Temperature-dependent NMR measurements were conducted between 180 K and 410 K.

Experimental results

Phase transition temperature

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments were carried out on the [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 crystal, employing heating and cooling rates of 10 °C/min with a sample amount of 4.8 mg. As depicted in Fig. 1, two very weak endothermic peaks were observed at 268 K and 291 K during heating, and the enthalpies for these peaks determined to be 228.27 and 238.70 J/mol, respectively. Conversely, exothermic peaks attributed to cooling were observed at 263 K and 288 K. Importantly, the phase transition temperatures observed during both the heating and cooling processes were reversible. In order to confirm the previously reported phase transition temperatures of 291.5 and 292.1 K, DSC experiments were conducted at a heating rate of 5 °C/min, but the same results were observed as when the heating rate was 10 °C/min. The previously reported phase transitions at 291.5 and 292.1 K were not distinguished. The results at 268 K and 291 K, as shown in the magnified inset in Fig. 1, were in good agreement with the results of Sawada et al50. but did not match well with the results of Mashiyama and Tanisaki36. As shown in Scheme 1, above 291 K is denoted as phase I, between 291 and 268 K as phase II, and below 268 K as phase III.

Single-crystal XRD results

SCXRD experiments were conducted on the [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 crystal at temperatures of 250, 275, and 300 K, and the crystal structures and lattice parameters were determined. At phase III (250 K), the crystal structure exhibited monoclinic symmetry with the space group P21/n and lattice parameters of a = 9.0412 Å, b = 37.0067 Å, c = 15.5885 Å, β = 90.3000°, and Z = 12. At phase II (275 K), the structure adopted an orthorhombic configuration with the space group Pna21, possessing lattice constants of a = 9.0512 Å, b = 24.7198 Å, c= 15.6415 Å, and Z = 8 (Supplementary Information 1). While these results largely agree with previously reported lattice constants36, slight discrepancies were exhibited, particularly in the β angle, which was 90° instead of 89.96°, and the crystal system was orthorhombic rather than monoclinic. Transitioning to phase I (300 K), the single crystal displayed an orthorhombic structure with the space group Pnma and lattice constants of a = 9.0837 Å, b = 12.3777 Å, c= 15.7211 Å, and Z = 4. The same reference for comparisons of lattice constants between the three phases is considered52. The detailed SCXRD results at 250 K and 300 K are provided in Table 1, and the bond-length and bond-angle at 300 K is presented in Table 2. Those at 250 K is shown in the Supplementary information 2. The single-crystal structure and atomic number for each atom in phase III are illustrated in Fig. 2(a) and (b), and those in phase I are represented in Fig. 3(a) and (b). The single crystal comprises [N(CH3)4]2 cations and MnCl4 anions, with Mn atoms surrounded by four Cl atoms. The difference in the crystal structure between 250 K and 300 K shown in Figs. 2 and 3 was the increase of different N and Mn sites, respectively. As the temperature increases, the Mn − Cl (2.3554 Å at 250 K and 2.3477 Å at 300 K), N − C (1.4618 Å at 250 K and 1.4188 Å at 300 K), and C − H (0.97 Å at 250 K and 0.96 Å at 300 K) lengths decrease, which is consistent with a decrease in the b-axis length. Crystallographic data for temperatures of 250 K and 300 K, including CIF files, were deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC 2327178 and 2366758).

Thermodynamic properties

The TGA experiment was conducted using a 12.23 mg sample across a temperature range of 300 to 973 K, and the results are presented in Fig. 4. Additionally, the morphology of the [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 single crystal, characterized by its yellow colour, is depicted in the inset of Fig. 4. The TGA analysis revealed that this crystal maintained thermal stability up to 669 K; however, at 669 K, the initial weight loss of [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 commenced, leading to partial decomposition with a weight loss of 2%. Furthermore, the TGA curve revealed a two-stage decomposition process at elevated temperatures. The remaining solid content was calculated from the TGA results and the molecular weight. From these observations, the sharp peak near 700 K in the DTA curve corresponds to a weight loss of 32%, attributed to the decomposition of [N(CH3)4Cl], whereas the peak near 900 K primarily reflects a weight loss of 63%, indicative of the decomposition of 2[N(CH3)4Cl].

1H and13C MAS NMR chemical shifts

The structural analysis of 1H in [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 was conducted via MAS NMR at a frequency of 400.13 MHz under a magnetic field of 9.4 T. At 300 K, [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 exhibited only one 1H NMR signal, as illustrated in the inset of Fig. 5. An experiment with a spinning rate of 10 kHz revealed a sideband distance around the 1H signal of 10 kHz (= 25 ppm), akin to the spinning rate. The main peak and sidebands are indicated by arrows and *, respectively. This composite structure arose from the chemical shift distribution and anisotropy at numerous inequivalent proton sites in the tetramethyl groups. Specifically, at room temperature, the NMR spectrum consisted of a single peak at a chemical shift of 2.27 ppm, attributed to the methyl proton. As shown in Fig. 5, the1H NMR chemical shift continuously shifted upfield without anomalous changes near TC1 and TC2 as the temperature increased. This confirmed that, within the experimental error, no changes occurred in the1H NMR chemical shifts associated with the phase transitions.

The intensity changes with varying delay times for the 1H NMR spectra were recorded at a given temperature, and the relationship of the decay rate of the magnetization is defined by the spin‒lattice relaxation time T1ρ53,54,55:

where W(τ) and W(0) are the signal intensities at time τ and τ = 0, respectively. The 1H T1ρ values for [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 from the straight slope of the intensity vs. delay time were obtained via Eq. (1). The 1H T1ρ values for [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 were determined from the straight slope of the intensity vs. delay time using this equation. These T1ρ values were found to be on the order of a few microseconds and slightly increased with increasing temperature, as shown in Fig. 5. The lower values of 1H T1ρ on the order of microseconds are attributed to the fact that T1ρ is inversely proportional to the square of the magnetic moment of paramagnetic Mn2+ ions.

The experimental values of T1ρ can be expressed by the correlation time τC for reorientational motion, and the T1ρvalue for molecular motion is given by Eq. (2)54:

In the equation, R is a constant; ω1 represents the rf power of the spin‒lock pulse; and ωC and ωH are the Larmor frequencies for carbon and protons, respectively. Local field fluctuations are induced by thermal motion, which is activated by thermal energy. T1ρ is typically expressed as an Arrhenius-type equation based on the activation energy Ea for molecular motion and temperature. Here, Ea represents the activation energy, and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The logarithmic scale of T1ρ, represented by blue squares vs. 1000/temperature, is depicted in Fig. 5. The 1H T1ρ values slowly increase at all the temperatures measured here. At all temperatures, the behaviour of the 1H T1ρ values for Arrhenius-type motions indicates fast motion, expressed as τCω1 < < 1, where T1ρ−1 is proportional to exp(Ea/kBT). The activation energy Ea obtained from the straight slope of T1ρ vs. 1000/temperature shown in Fig. 5 is 1.32 ± 0.03 kJ/mol for1H.

In contrast, structural analysis of 13C in [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 was conducted via a 13C MAS NMR experiment. Figure 6 shows the temperature dependence of the 13C NMR chemical shifts. At 300 K, the 13C MAS NMR chemical shift, as shown in the inset of Fig. 6, was recorded at 254.62 ppm with respect to TMS, as observed for a powder sample. The sidebands are denoted as “o”, with the distance of the sideband around the 13C signal found to be 10 kHz (= 100 ppm), akin to the spinning rate. The 13C NMR peak shifted in the downfield direction from 349 to 200 ppm as the temperature increased, without any anomalous changes near TC1 and TC2. The significant shift difference likely arises from the varying strengths of the paramagnetic interactions with the unpaired electrons situated on the Mn2+ ions. From the changes in the 1H and 13C chemical shifts according to temperature, the structural geometry around 1H and13C can be inferred to continuously change.

The intensity changes of the 13C NMR spectra were also measured by increasing the delay time at a given temperature. The 13C T1ρ values were obtained by varying the 13C spin-locking pulse sequence applied after cross-polarization (CP) preparation. The 13C magnetization was generated by CP after spin locking of the protons. The proton field was then turned off for a variable time τ, while the 13C rf field remained on. Finally, 13C free induction decay was observed during high-power proton decoupling and was subsequently Fourier transformed. The values of T1ρ were selectively obtained via Fourier transformation of the free-induction decay after spin locking and repetition of the experiment with variations in the time τ. The 13C T1ρ values were derived from the slope of their recovery traces via Eq. (1), and these T1ρ values for 13C are depicted in Fig. 6. The 13C T1ρ value at 300 K is 4.28 ms, and the 13C T1ρ values are approximately 500 times greater than the 1H T1ρ values. On the other hand, the T1ρ values near TC2 continuously increase as the temperature increases without any anomalous changes, whereas those near TC1 exhibit discontinuous changes. The sudden decrease in T1ρ values from low to high temperatures indicates a sudden variation in the carbon dynamics at TC1, which originates from the slowing motion of the molecular dynamics across the phase transition at TC1. The activation energy Ea values obtained from the slope of T1ρ vs. 1000/temperature shown in Fig. 6 are 0.37 ± 0.29 kJ/mol and 1.72 ± 0.16 kJ/mol at low and high temperatures for 13C, respectively. The small values of Ea at low and high temperatures indicate high degrees of freedom for the methyl group. The 13C T1ρ values are divided into fast motion (τCω1 < < 1, T1ρ[-1 α exp(Ea/kBT)) and slow motion (τCω1 > > 1, T1ρ α ω1-2 exp(Ea/kBT)). The T1ρ values below TC1 are attributed to fast motion, whereas the T1ρ values above TC1are attributed to slow motion54.

14N static NMR resonance frequency

The NMR spectrum of 14N (I = 1) was obtained in the temperature range of 180–420 K via the solid-state echo method in a laboratory frame at a Larmor frequency of ωo/2π = 28.90 MHz. The 14N resonance frequency range exhibited a significantly wider span than the 1H and 13C chemical shift ranges did, making it valuable for determining the surrounding environment of 14N. The crystal orientation with respect to the external magnetic field was measured along an arbitrary direction of the single crystal. The two resonance lines arise from the quadrupole interaction of the 14N nucleus. The temperature-dependent 14N resonance frequency of [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 single crystals is shown in Fig. 7. However, owing to the very low Larmor frequency for obtaining the 14N NMR spectrum, the intensity of the 14N signals was so small that it was not easy to measure, as shown in the inset of Fig. 7. At temperatures below TC1, several low intensity 14N signals were observed, but they could not be accurately distinguished. The splitting near TC1 is due to a phase transition phenomenon. The electric field gradient (EFG) tensor at the N sites varies, reflecting configuration changes of atoms neighbouring the 14N nuclei53. In addition, the 14N NMR spectra exhibit four signals above TC1, attributed to the N(1) and N(2) sites in the two inequivalent N(1)(CH3)4 and N(2)(CH3)4 ions, respectively. The 14N resonance frequency decreases as the temperature increases, as shown in Fig. 7. The same pairs for 14N are indicated by the same symbols. The N(CH3)4 in the structure is coordinated by CH3, and the atomic displacements in the environments of the14N nuclei with temperature are correlated with the CH3 ions.

Conclusion

The phase transition temperatures of the organic–inorganic perovskite [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 single crystals grown here were observed at 268 K (TC2) and 291 K (TC1) via DSC and SCXRD experiments. On the basis of phase transition temperatures of 268 K and 291 K, the structures in phases III, II, and I were determined to have monoclinic, orthorhombic, and orthorhombic symmetry, respectively, and their thermodynamic stability was confirmed to reach approximately 669 K. Additionally, the NMR chemical shifts of the [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 crystal were analysed to understand the nature of the structural geometry near TC1 and TC2. 1H and 13C chemical shifts change continuously without rapid anomalous changes according to temperature changes, but 14N chemical shifts show discontinuous changes near TC1. The discontinuous change in the 14N resonance frequency near TC1 was attributed to the structural phase transition, with the main factor for TC1 being the change in structural geometry surrounding the 14N nuclei in the N(CH3)4 groups; the observation of multiple 14N signals near TC1 and TC2 is consistent with the SCXRD experimental results, which show that the number of different N sites (see Fig. 2(b) and 3(b)) increases as the temperature decreases. On the other hand, the T1ρ values, which represent the extent of energy transfer surrounding the 1H and 13C atoms of the cation, were discussed to understand the nature of the molecular motions near TC1 and TC2. The energy transfer of 1 H and 13C was significantly different; the shorter1H T1ρ than the 13C T1ρ indicates easier energy transfer for 1H. Also, the reason why [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 has very short values of 1H T1ρ is because this has a paramagnetic ion, Mn2+, around it. The sudden change in 13C T1ρ near TC1 indicates a sudden variation in energy transfer surrounding the carbons; 1H T1ρ does not exhibit any anomalous changes near TC1 and TC2, while 13C T1ρ shows changes near TC1, which is thought to affect energy transfer due to the bonding of 14N to 13C in N(CH3)4 group. Additionally, on the basis of the temperature dependence of T1ρ for1H and 13C, the activation energies Ea for the molecular motion of the N(CH3)4 groups, indicating that these values are governed by the large degree of freedom for the molecular motions of organic cations, were considered. The Ea value of 13C in phase I (1.72 kJ/mol) is approximately 5 times greater than the values in phases III and II (0.37 kJ/mol). This suggests that the CH3 groups move more easily and freely in phases III and II, whereas the molecular motion in phase I is primarily dominant in the overall N(CH3)4. On the basis of the basic mechanism of [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 crystals, potential applications in various fields are expected to be possible.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are deposited in Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC 2327178 and 2366758).

References

Simenas, M. et al. Spectroscopic study of [(CH3)2NH2] [Zn(HCOO)3] hybrid perovskite containing different nitrogen isotopes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 10284 (2018).

Hoefler, S. F., Trimmel, G. & Rath, T. Progress on lead-free metal halide perovskites for photovoltaic applications: a review. Monatsh Chem. 148, 795 (2017).

Abhyankar, N. et al. Understanding ferroelectricity in the Pb-free perovskite-like metal–organic framework [(CH3)2NH2]zn(HCOO)3: Dielectric, 2D NMR, and theoretical studies. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 6314 (2017).

Simenas, M., Ciupa, A., Maczka, M., Poppl, A. & Banys, J. EPR Study of structural phase transition in manganese-doped [(CH3)2NH2][Zn(HCOO)3] metal–organic framework. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 24522 (2015).

Asaji, T. & Ashitomi, K. Phase transition and cationic motion in a metal–organic perovskite, dimethylammonium zinc formate [(CH3)2NH2][Zn(HCOO)3]. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 10185 (2013).

Asaji, T. et al. Phase transition and ring-puckering motion in a metal–organic perovskite [(CH2)3NH2][Zn(HCOO)3]. J. Phys. Chem. A. 116, 12422 (2012).

Rao, C. N. R., Cheetham, A. K. & Thirumurugan, A. Hybrid inorganic–organic materials: a new family in condensed matter physics. J. Phys. : Condens. Matter. 20, 083202 (2008).

Chen, Q. et al. Under the spotlight: the organic–inorganic hybrid halide perovskite for optoelectronic applications. Nano Today. 10, 355 (2015).

Jellali, H. et al. Zn2+ and Cu2+ doping of one-dimensional lead-free hybrid perovskite ABX3 for white light emission and green solar cell applications. Mater. Res. Bull. 151, 111819 (2022).

Shao, T. et al. F. 2D lead-free organic–inorganic hybrid exhibiting dielectric and structural phase transition at higher temperatures, CrystEngComm. 24, 4346 (2022).

Han, K. et al. Organic–inorganic hybrid compound [H2-1,5-Diazabicyclo[3.3.0]octane]ZnBr4 with reverse symmetry breaking shows a switchable dielectric anomaly and robust second harmonic generation effect. Inorg. Chem. 61, 11859 (2022).

Su, C. et al. Hybrid optical-electrical perovskite can be a ferroelastic semiconductor. CCS Chem. 3, 2021 (2021).

Kalthoum, R., Bechir, M. B., Rhaiem, A. B. & Gargouri, M. MCdCl3 (M = CH3NH3, (CH3)2NH2): new hybrid perovskites with large dielectric constants for field-effect transistors. Phys. Status Solidi A. 218, 2100485 (2021).

Lee, J., Lee, W., Kang, K., Lee, T. & Lee, S. K. Layer-by-layer structural identification of 2D ruddlesden–popper hybrid lead iodide perovskites by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 33, 370 (2021).

Ahmad, K. & Mobin, S. M. Organic–inorganic copper (II)-based perovskites: a benign approach toward low-toxicity and water-stable light absorbers for photovoltaic applications. Energy Technol. 8, 1901185 (2020).

Rok, M. et al. Advances and property investigations of an organic–inorganic ferroelectric: (diisopropylammonium)2[CdBr4]. Inorg. Chem. 59, 11986 (2020).

Wang, Z. X. et al. Superior transverse piezoelectricity in a halide perovskite molecular ferroelectric thin film. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12857 (2020).

Simenas, M. et al. Elucidation of dipolar dynamics and the nature of structural phases in the [(CH3)2NH2][Zn(HCOO)3] hybrid perovskite framework. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 6779 (2019).

Milic, J. V. et al. Supramolecular engineering for formamidinium-based layered 2D perovskite solar cells: structural complexity and dynamics revealed by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1900284 (2019).

Mondal, P., Abdel-Aal, S. K., Das, D. & Islam, S. M. Catalytic activity of crystallo-graphically characterized organic–inorganic hybrid containing 1,5-Di-amino-pentane tetrachloro manganate with perovskite type structure. Catal. Lett. 147, 2332 (2017).

Simenas, M. et al. Electron paramagnetic resonance and electric characterization of a [CH3NH2NH2][Zn(HCOO)3] perovskite metal formate framework. J. Mater. Chem. C. 5, 4526 (2017).

Rong, S. S., Faheem, M. B. & Li, Y. B. Perovskite single crystals: synthesis, properties, and applications. J. Electro Sci. Tech. 19, 100081 (2021).

Kim, N. H. & Lim, A. R. Structural characteristics for phase transitions of [N(CH3)4]2CuCl4 by 13C CP/MAS NMR and 14N NMR. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 70, 43 (2015).

Lim, A. R. & Lim, K. Y. Study of phase transition mechanisms in [N(CH3)4]2ZnCl4 by static NMR and MAS NMR. Solid State Sci. 31, 70 (2014).

Lim, A. R. Roles of chemically inequivalent N(CH3)4 ions in phase transition temperatures in [N(CH3)4]2CoCl4 by single-crystal NMR and MAS NMR. Chem. Phys. 436–437, 46 (2014).

Lee, S. J. & Lim, A. R. Structural characteristics of [N(CH3)4]2CdCl4 determined by 1H MAS NMR, 13C CP/ MAS NMR, and 14N NMR. J. Korean Magn. Reson. 19, 18 (2015).

Pasciak, M., Wolcyrz, M. & Pietraszko, A. Structural origin of the x-ray diffuse scattering in (CH3)4NCdCl3 and related compounds. Phys. Rev. B. 78, 024114 (2008).

El-Korsahy, A. & Brik, M. G. Crystal growth, spectroscopic and crystal field studies of [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 and [N(CH3)4]2CoCl4 single crystals in the paraelectric phase. Solid State Commun. 135, 298 (2005).

Batyuk, A. Y., Kapustyanyk, V. B. & Korchak, Y. M. Manifestations of phase transitions and the thermooptical-memory effect in the absorption spectra of (N(CH3)4)2CuCl4 crystals. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 72, 413 (2005).

Abu El-Fadl, A., El-Korashy, A. & El-Zahed, H. Electrical investigations in the normal and incommensurate phases of [N(CH3)4]2ZnCl4 single crystals. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 63, 375 (2002).

Koshiji, N., Miyoshi, T. & Mashiyama, H. Electron density distribution of the commensurate phase of TMATC-Mn. Ferroelectrics. 440, 119 (2012).

Koshiji, N. & Mashiyama, H. Structural study of ordering in the normal-commensurate transition of {N(CH3)4}MnCl4. J. Phys. Soc. Japan. 80, 64602 (2011).

Brik, M. G., El-Korashy, A. & Almokhtar, M. Exchange charge model calculations of crystal field parameters and crystal field energy levels for [N(CH3)4]2CoCl4 and [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 single crystals. J. Alloys Com. 459, 71 (2008).

Koshiji, N. & Mashiyama, H. Disordered and displacive models for the structure of the normal phase in {N(CH3)3}2MnCl4. J. Phys. Soc. Japan. 69, 3853 (2000).

Koksal, F., Bahadir, S., Basaran, E. & Yerli, Y. Temperature independent isotropic EPR spectra of [(CH3)4N]2MnCl4 and [(CH3)4N]2FeCl4 single crystals. Z. Naturforsch. 54a, 557 (1999).

Mashiyama, H. & Koshiji, N. A structural study of phase transitions in [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4, Acta Cryst. B45, 467 (1989).

Marco de Lucas, M. C. & Rodriguez, F. Evidence of a new first-order phase transition at 92 K in ((CH3)4N)2MnCl4 single crystals. J. phys. : Condens. Matter. 1, 4251 (1989).

Zubillaga, J., Lopez-Echarri, A. & Tello, M. J. The incommensurate phase in tetramethylammonium tetrachloromanganate. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 21, 4417 (1988).

Mashiyama, H. & Tanisaki, S. Incommensurate-commensurate phase transition of {N(CH3)4}2MnCl4. J. Phys. Soc. Japan. 50, 1413 (1981).

El-Korashy, A., El-Zahed, H. & Radwan, M. Optical studies of [N(CH3)4]2CoCl4, [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 single crystals in the normal paraelectric phase. Phys. B. 334, 75 (2003).

Bolesta, I., Furgala, Y. & Kityk, I. Effects of phase transitions in luminescience features of [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 single crystals. Ferroelectrics. 56, 1 (1996).

Marco de Lucas, M. C., Rodriguez, F. & Moreno, M. Optical investigations on {N(CH3)4}2MnCl4: a new phase transition at 90 K. Ferroelectrics. 109, 21 (1990).

Fuith, A., Schranz, W., Warhanek, H., Kroupa, J. & Lhotska, V. Optical investigations in [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4. Phase Transitions. 27, 15 (1990).

Shimomura, S., Hamaya, N. & Fujii, Y. High-resolution X-ray diffraction study of commensurate- incommensurate phase transition in [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 under pressure. J. Phys. Soc. Japan. 65, 661 (1996).

Shimomura, S., Hamaya, N. & Fujii, Y. Systematics in the commensurate-incommensurate phase transition in [N(CH3)4]2MCl4 (M = zn, Fe, and Mn) under pressure. Phys. Rev. B. 53, 8975 (1996).

Hamaya, N., Shimomura, S. & Fujii, Y. Systematics in the modulated phases of [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4. J. Phys. : Condens. Matter. 3, 3387 (1991).

Hamaya, N. et al. X-ray diffraction study of phase transitions in [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 under pressure. Solid State Commun. 67, 329 (1988).

Gesi, K. & Ozawa, K. Effect of hydrostatic pressure on the phase transitions in {N(CH3)4}2MnCl4. J. Phys. Soc. Japan. 53, 627 (1984).

Shimizu, H. et al. Differential thermal analysis using a Ge-Ag thermocouple under hydrostatic pressure: phase behavior of {N(CH3)4}2MnCl4. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 18, 857 (1979).

Sawada, S., Shiroishi, Y., Yamamoto, A., Takashige, M. & Matsuo, M. presented at the 33rd Annual Meeting of the Physical Society of Japan, (1978).

SHELLXTL v6.10 & Bruker, A. X. S. Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA (2000).

Liang, B. D. et al. Near-room-temperature martensitic actuation profited from one-dimensional hybrid perovskite structure. Nat. Commun. 13, 6599 (2022).

Abragam, A. The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism (Oxford University Press, 1961).

Koenig, J. L. Spectroscopy of Polymers (Elsevier, 1999).

Harris, R. K. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (Pitman Pub.: UK,, 1983).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (2023R1A2C2006333) and from the Basic Science Research Program through the NRF of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2016R1A6A1A03012069).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R. Lim wrote the main manuscript, and A.R. Lim measured XRD, NMR experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, A.R. Crystal structure, structural geometry, and molecular motion of organic–inorganic perovskite [N(CH3)4]2MnCl4 crystals at phases I, II, and III. Sci Rep 14, 26607 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78376-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78376-5

This article is cited by

-

A comprehensive study of the crystal structure and dynamics of [N(C3H7)4]2Cd2Cl6

Scientific Reports (2026)