Abstract

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a global health crisis, including ocular symptoms, primarily targeting the Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. PM2.5 air pollution may increase infection risk by altering ACE2 expression. Silicon Dioxide (SiO2) and carbon black (CB), major components of PM2.5 from sands and vehicle emissions, were studied for their effects on ACE2 and Transmembrane Protease Serine 2 (TMPRSS2) expression in corneal and conjunctival cells, and ocular tissues. Human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs) and conjunctival epithelial cells (HCjECs) were exposed to nanoparticles (NPs) for 24 hours, assessing viability via WST-8 assay. TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels in the medium were measured. An in vivo rat study administered NPs via eye drops, with Rose Bengal staining to evaluate damage. ACE2, TMPRSS2, and Angiotensin II (AngII) protein expressions were quantified by Western blot. ACE2 expression in HCjECs increased with NP exposure, while it decreased in HCECs. CB exposure increased TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels in HCECs. In vivo, corneal exposure to CB decreased ACE2 expression, whereas conjunctival exposure to SiO2 increased ACE2 expression. These changes suggest that SiO2 exposure may increase the risk of COVID-19 through the ocular surface, while CB exposure may decrease it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global outbreak of COVID-19 caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) presents an urgent need to understand the mechanisms of its viral transmission and to identify effective preventive measures. COVID-19 is caused by SARS-CoV-2, a newly emerged coronavirus that was first reported in Wuhan, China in December 20191. SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to a range of symptoms, including respiratory symptoms (such as cough, fever, and shortness of breath), muscle pain, fatigue, chest pain, sore throat, headache, and loss of smell or taste2,3,4. Severe cases may result in pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiple organ failure, or even death5. Some studies have suggested that the novel coronavirus can also cause symptoms in the ocular surface6.

SARS-CoV-2 uses its spike protein to bind to ACE2 receptors on the surface of host cells, facilitating its entry into the cell7,8. TMPRSS2 is a human cell surface protease that facilitates fusion of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 with the host cell membrane, thereby promoting viral entry into host cells9. ACE2 is a critical component in regulating the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in the human body. ACE2 converts angiotensin Ang I to Ang (1-9) and degrades Ang II into Ang (1-7)10. Ang II promotes pro-inflammatory responses, fibrosis, and vasoconstriction. Ang (1-7) is an anti-proliferative, and anti-apoptotic peptide that acts as a vasodilator. The ACE2 protein is expressed in various tissues, including the oral and nasal mucosa, nasopharynx, lungs, skin, lymphatic system, liver, stomach, small intestine, colon, kidney, brain, heart, vascular endothelial, and smooth muscle cells11. Studies have shown that the ACE2 protein is expressed in the limbus, cornea, conjunctiva, and retina tissues of the ocular surface6,12. ACE2 is involved in regulating pathophysiological changes in the human body; it is also associated with tissue injury, inflammation, and the development of chronic diseases10,13. Notably, ACE2 also serves as the receptor for severe acute respiratory SARS-CoV-214.

Recent studies have shown that exposure to PM2.5 particles may increase the expression of ACE2 receptors in the lungs and cardiovascular system, which makes it easier for the SARS-CoV-2 virus to invade cells and worsen COVID-19 symptoms15,16. PM2.5 refers to microscopic particles that are suspended in the air, including a complex mixture of solid and liquid materials such as dust, soot, and vehicle emissions17,18. SiO2 and CB are common components found in PM2.5 that can come from various sources, such as vehicle emissions, industrial processes, wildfires, and natural dust19,20. SiO2 is typically present in the form of quartz or cristobalite, and may be released into the air during sandstorms and construction activities19. CB particles are produced during incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, including those used for vehicle exhaust and power generation20. Exposure to PM2.5 can cause ocular inflammation and dry eye disease, as well as uncomfortable symptoms such as itching, burning, and stinging of the ocular surface21,22. Different components of PM2.5 can also cause varying degrees of damage to the ocular surface. Previous studies have shown that four different types of NPs (TiO2, ZnO, SiO2, CB) induce different levels of cytotoxicity and intracellular ROS response in HCECs and HCjECs23. While previous studies have shown that PM2.5 and its different particle components can induce inflammatory responses on the ocular surface, there has been relatively little research on whether these inflammatory responses have an impact on the expression of ACE2 on the ocular surface. Therefore, we aim to investigate the effects of dust and vehicle emissions, represented by SiO2 and CB NPs, respectively, on the ACE2 expression on ocular surface. We also investigated their potential impact on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Results

Cytotoxicity induced by SiO2 and carbon black

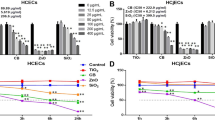

We found that the cytotoxicity of both NPs varied for the two cell types at different concentrations (0 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, 200 μg/ml). As the concentration of NPs increased, the cytotoxicity on both cell types increased to varying degrees. The cytotoxicities of both NPs were higher in the HCECs cell line than they were in the HCjECs cell line (Fig. 1A,B). SiO2 and CB exhibited significant toxicity in the HCECs cell line when the concentration reached 50 μg/ml (p < 0.01). However, in the HCjECs cell line, both SiO2 and CB NPs required a concentration of 100 μg/ml to induce toxicity (p < 0.05, p < 0.01). The two distinct NPs demonstrated varying degrees of cytotoxicity on HCjECs and HCECs. To induce cytotoxicity in both cell types simultaneously using SiO2 and CB particles, we selected the lowest concentration of SiO2 (100 μg/ml) that could effectively induce cytotoxicity in HCjECs . Consequently, we applied the same concentration of 100 μg/ml for both NPs in this experiment.

Cytotoxicity evaluation of SiO2 and CB NPs using the WST-8 assay(n=3). HCECs (A) and HCjECs (B) were treated with different concentrations (0, 50, 100, or 200 μg/ml) for 24 hours. Cell viability was determined using the WST-8 assay. The results were expressed as a percentage relative to untreated control cells. The experimental data represent the means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments, with each experiment performed in triplicate. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. controls.

Expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the supernatant of HCECs and HCjECs cells

After treating the cells with 100 μg/ml of SiO2 NPs for 24 hours, there was no significant increase in the concentration of TNF-α, IL-6, or IL-1β in the supernatant of HCECs compared to those of the control group. [The concentrations of TNF-α were 4.12 pg/ml (4.09-4.17) vs. 4.46 pg/ml (4.19-4.53), IL-6 426.01 pg/ml (344.52-497.57) vs. 505.02 pg/ml (456.33-551.60), and IL-1β 332.06 pg/ml (218.05-403.9 5) vs. 354.17 pg/ml (270.67-438.96 ) in the HCECs versus control groups, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2A, C, E.]. On the contrary, after treating the cells with 100 μg/ml of CB NPs for 24 hours, there was a significant increase in the concentration of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the supernatant of HCECs compared to those in the control group. [The concentrations of TNF-α were 4.12pg/ml (4.09-4.17) vs. 31.87 pg/ml (27.72-33.09) (p < 0.05), IL-6 426.01 pg/ml (344.52-497.57) vs. 628.33 pg/ml (588.44-652.71, p < 0.05), and IL-1β 332.06 pg/ml (218.05-403.95) vs. 770.12 pg/ml (608.96 935.04, p < 0.05) in the HCEC versus control groups, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2A, C, E.].

ELISA assays were performed on the supernatants of HCECs and HCjECs treated with 100 μg/ml of SiO2 and CB for 24 hours(n=3). (A) Expression of TNF-α in the supernatant of HCECs, *p<0.05. (B) Expression of TNF-α in the supernatant of HCjECs. (C) Expression of IL-6 in the supernatant of HCECs, *p<0.05. (D) Expression of IL-6 in the supernatant of HCjECs, *p<0.05. (E) Expression of IL-1β in the supernatant of HCECs, *p<0.05. (F) Expression of IL-1β in the supernatant of HCjECs.

After treating HCjECs cells with 100 μg/ml of SiO2 NPs for 24 hours, there was no significant change in the concentration of TNF-α, IL-6, or IL-1β in the supernatant compared to those in the control group. [The concentrations of TNF-α were 3.04 pg/ml (2.88 pg/ml-3.20 pg/ml) vs. 3.07 pg/ml (3.00 pg/ml-3.15 pg/ml), IL-6 43.38 pg/ml (35.95 pg/ml-48.16 pg/ml) vs. 37.42 pg/ml (29.28 pg/ml-44.70 pg/ml), and IL-1β 267.15 pg/ml (208.81 pg/ml-310.14 pg/ml) vs. 258.09 pg/ml (192.44 pg/ml-297.30 pg/ml) in the HCjEC versus control cells, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2B, D, F]. After treating the HCjECs cells with 100 μg/ml of CB NPs for 24 hours, there was no significant change in the concentration of TNF-α or IL-1β in the supernatant compared to those in the control group. [The concentrations of TNF-α were 3.04 pg/ml (2.88-3.20) vs. 2.92 pg/ml (2.81-3.02), and IL-1β were 267.15 pg/ml (208.81 pg/ml-310.14) vs. 310.09 pg/ml (233.00-361.43) in the HCjEC versus control groups, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2B, F]. The concentration of IL-6 in the supernatant of HCjECs was higher [60.62 pg/ml (55.95-65.94)] than that in the control group [43.38 pg/ml (35.95-46.02)], as shown in Fig. 2D ( p < 0.05).

Effects of SiO2, CB exposure on the expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2 and AngII in HCECs and HCjECs

The expression of ACE2 in HCECs decreased upon exposure to SiO2 and CB, with a more pronounced decrease observed with CB exposure (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001, Fig. 3A). Similarly, exposure of HCECs to SiO2 and CB resulted in an increased expression of AngII, with a more significant increase observed with CB exposure (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001, Fig. 3C). In contrast, ACE2 expression in HCjECs increased upon exposure to SiO2 and CB, with a more pronounced increase observed with SiO2 exposure (**p<0.01, *p<0.05, Fig. 3D). AngII expression, however, significantly decreased in HCjECs upon SiO2 exposure (***p<0.001, Fig. 3F). These results indicate a potential association between ACE2 expression and cellular activity in HCECs and HCjECs, with an inverse correlation between ACE2 expression and AngII expression. There were no significant changes in the expression of TMPRSS2 in either HCECs or HCjECs (Fig. 3B, E)

Expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and AngII in HCECs and HCjECs after 24-hour exposure to SiO2 and CB(n=3). (A) Expression of ACE2 in HCECs exposed to 100ug/ml SiO2 and CB. (B) Expression of TMPRSS2 in HCECs exposed to 100ug/ml SiO2 and CB. (C) Expression of AngII in HCECs exposed to 100ug/ml SiO2 and CB. (D) Expression of ACE2 in HCjECs exposed to 100ug/ml SiO2 and CB. (E) Expression of TMPRSS2 in HCjECs exposed to 100ug/ml SiO2 and CB. (F) Expression of AngII in HCjECs exposed to 100ug/ml SiO2 and CB. Representative Western blot images are shown in the upper left corner of each panel. β-actin was used as an internal loading control. The results are presented as the ratio to β-actin, indicating the relative expression levels.

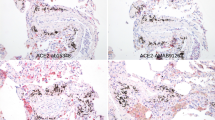

Rose Bengal staining score of the ocular surface

Rose Bengal staining score results of the ocular surface in rats. (Fig. 4A, B). The SiO2 and CB groups exhibited higher Rose Bengal staining scores than did the control group, with a more significant increase observed in the CB group (*p<0.05).

Effects of SiO2 and CB exposure on the expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and AngII in rat corneal and conjunctival tissues

ACE2, TMPRSS2, and AngII expression in the corneal and conjunctival tissues of rats The results showed that exposure of the corneal tissue to CB led to a significant decrease in ACE2 expression (*p<0.05, Fig. 5A), while the AngII expression increased (*p<0.05, Fig. 5C). In contrast, the expression of ACE2 in the conjunctival tissue did not significantly change upon CB exposure. The expression of TMPRSS2 did not show significant changes in either the conjunctiva or the cornea(Fig. 5B,E).However, AngII expression was upregulated. Exposure of the conjunctival tissue to SiO2 resulted in a significant increase in ACE2 expression compared to that in the control group (*p<0.05, Fig. 5D,F), while AngII expression remained unchanged. These findings were inconsistent with the results of the in vitro experiments in this study. Based on our findings, we speculate that exposure of the corneal tissue to CB can induce a pronounced inflammatory response, leading to a decrease in ACE2 expression. Therefore, corneal exposure to CB may potentially reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 binding to ACE2 receptors in the corneal tissue. In contrast, exposure of the conjunctival tissue to SiO2 may enhance the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 binding to ACE2 receptors in the conjunctival tissue.

After eye drops of 2mg/ml SiO2 and CB were applied, we observed the expressions of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and AngII in rat corneal and conjunctival tissues(n=6). (A) ACE2 expression in rat corneal tissue after eye drop treatment with SiO2 and CB. (B) TMPRSS2 expression in rat corneal tissue after eye drop treatment with SiO2 and CB. (C) AngII expression in rat corneal tissue after eye drop treatment with SiO2 and CB. (D) ACE2 expression in rat conjunctival tissue after eye drop treatment with SiO2 and CB. (E) TMPRSS2 expression in rat conjunctival tissue after eye drop treatment with SiO2 and CB. (F) AngII expression in rat conjunctival tissue after eye drop treatment with SiO2 and CB.

Discussion

Previous studies have indicated that many patients develop ocular complications following COVID-19. In a survey of 2,347 confirmed COVID-19 patients, 11.64% were found to have ocular diseases, with external ocular diseases being the most common (including discomfort, redness, discharge, and follicular conjunctivitis)24. In their retrospective study of 534 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, Chen et al. observed that 85 patients (at an overall rate of 16%) had concurrent ocular diseases including conjunctivitis, dry eye syndrome, keratitis, cataracts, and a history of diabetic retinopathy25. Ocular diseases often cause and increase the duration of hand-eye surface contact. Several studies have suggested that contact with tears may be a major route for viral transmission26.

Several studies have suggested that ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are expressed on the ocular surface. Multiple animal models have demonstrated that Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Spike Protein (SARS-2-S) can be transmitted through ocular inoculation6,27. SARS-2-S utilizes ACE2 as a cellular receptor, and the serine protease TMPRSS2 to activate entry into cells8. After binding to the ACE2 receptor on host cells, SARS-2-S enters the cells and uses their cellular machinery to replicate and proliferate14.

This study aims to analyze whether exposure of the ocular surface to SiO2 and CB affects the expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2. This question was asked in order to determine whether SiO2 and CB exposure influences the mode of SARS-CoV-2 infection through the ocular route. We initially conducted in vitro experiments, which revealed that exposure to SiO2 and CB led to decreased ACE2 expression in HCECs, but increased expression in HCjECs. Furthermore, we observed an increase in the expression of the pro-inflammatory factor AngII in HCECs, while it decreased in HCjECs. Additionally, while there was no change in the ACE2 expression in corneal tissues exposed to SiO2, it increased significantly in the conjunctival tissues. Conversely, exposure to CB led to a decrease in ACE2 expression in corneal tissues, with no change in ACE2 expression in conjunctival tissues.

Previous studies have shown that PM2.5 exposure in mice significantly increases ACE2 expression in the lungs, which may facilitate entry of SARS-CoV-2 during infection15,16. In the current study, exposure of conjunctival cells to SiO2 resulted in increased expression of ACE2, potentially increasing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection via the conjunctiva. Conversely, exposure of corneal cells to CB resulted in a significant decrease in ACE2 expression, which may reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection via the cornea.

In this study, HCECs and HCjECs exhibited different levels of cytotoxicity under SiO2 and CB stimulation. The HCECs showed a more significant decrease in cell viability after exposure than did HCjECs. In the in vitro experiment, the expression of ACE2 in the CB group of HCECs showed a significant downward trend compared with that of the control group. In contrast, the AngII expression was significantly increased. In the RAS system, AngII induces inflammatory reactions, including the release of cytokines and chemokines, leukocyte infiltration, and expression of matrix metalloproteinases28. AngII binds to the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) to activate downstream signaling pathways, thereby inhibiting ACE2 expression29. Specifically, the signal transduction pathway of AngII can inhibit the transcription and translation of the ACE2 gene, which reduces the expression of the ACE2 protein. In addition, AngII can promote the internalization of ACE2, leading to its degradation in the cell30. To further confirm whether CB induces inflammation in HCECs, we used ELISA to detect the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. The results showed that these inflammatory factors increased in the CB group. The expression of ACE2 increased in the HCjECs exposed to SiO2. Previous studies have shown that PM2.5 induces cytotoxicity in pulmonary bronchial epithelial cells, inhibits cell proliferation, and induces cell apoptosis; these changes increase the intracellular ROS levels and upregulate ACE2 expression31. According to previous studies, different particles in PM2.5 induce varying levels of cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and ROS expression. Unlike CB, SiO2 showed a slight increase in ROS production, but did not induce cell apoptosis in HCjECs23. In this study, compared to CB, the cell activity of the SiO2 group remained almost unchanged. There were no significant increases in TNF-α, IL-6, or IL-1β. Therefore, we speculate that mild stimulation may cause an increase in ACE2 expression, but excessive toxicity may lead to a decrease in ACE2 expression. The expression of ACE2 was upregulated in HCjECs, while the expression of AngII was decreased. Previous studies have shown that ACE2 can reduce the activity of AngII by degrading it. ACE2 has amino peptidase activity against AngII, which hydrolyzes it into the less active ANG (1-7) to inhibit inflammation32.

In an in vivo experiment, we evaluated the effects of exposure to different types of particles on ocular tissues. Rose Bengal scoring showed that all experimental groups had varying degrees of damage to the ocular surface, but CB caused more significant damage than did SiO2. We also observed an increase in the expression of AngII in both the conjunctiva and cornea in the CB group, indicating the presence of inflammation. Additionally, we found that ACE2 expression was decreased in the CB group. We further compared the in vivo and in vitro experiments and found that the changes in ACE2 expression were more pronounced in the in vitro experiment. This may be because we used corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells in the in vitro experiment, but we were unable to analyze the epithelial cells alone in the in vivo experiment. ACE2 is expressed more abundantly in epithelial cells6. In addition, we observed the expression of TMPRSS2 in both in vivo and in vitro experiments in this study, but there was no significant difference between the groups.

ACE2 expression is present in both the conjunctiva and cornea, but the expression is higher in the conjunctiva. Leonardi et al. analyzed the expression of ACE2 in conjunctival and corneal cells, and found that the ACE2 expression was lower in corneal samples (0.1%) than it was in conjunctival samples (0.26-1%)33. It has been reported that this disease can be transmitted through mucous membranes, including the conjunctiva34. According to reports, positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR results were obtained from conjunctival swab samples collected from patients with conjunctivitis, while negative results were obtained from patients without conjunctivitis26. One explanation for why conjunctivitis patients may be more likely to show a positive level of SARS-CoV-2 RNA is that conjunctivitis may be caused by the active presence of SARS-CoV-2. In one patient, RT-PCR testing showed the presence of viral RNA in conjunctival specimens 13 days after onset of symptoms, and these specimens remained SARS-CoV-2 positive 14 and 17 days after symptom onset. In another report, a hospitalized patient had a positive SARS-CoV-2 result on conjunctival swabs for up to 21 days after symptom onset despite no detectable virus in the nasal swabs a few days after symptoms onset. Five days later, the virus was not detected in conjunctival swabs, but was detected again on day 27, indicating ongoing viral replication in the conjunctiva35. Therefore, conjunctivitis is not only a potential complication of COVID-19, but also may be one of the routes of COVID-19 transmission. Shengjie Li et al. demonstrated that compared to normal conjunctival epithelial cells, ACE2 is significantly overexpressed in diseased epithelial cells36. Colin et al. showed that local inflammation can enhance ACE2 expression, which can explain why ACE2 is expressed at higher levels in diseased conjunctiva37.

In the in vivo experiments, continuous SiO2 exposure induced inflammatory responses on the ocular surface of Rats, which was accompanied by an increase in ACE2 expression in conjunctival tissue. We believe that this overexpression of ACE2 may increase the likelihood of COVID-19 infection through the conjunctival tissue. However, when exposed to CB, the inflammatory response was significantly more pronounced than it was with SiO2 exposure. However, upon CB exposure, the ACE2 expression decreased in the corneal tissue, potentially reducing the likelihood of COVID-19 infection through the cornea.

Previous studies have indicated that differences in the chemical composition of PM2.5 can impact toxicological responses. The cytotoxicity of NPs depends on various factors such as the cell type, particle characteristics, as well as exposure concentration and duration23. There is substantial evidence demonstrating the influence of PM2.5 on ACE2 expression, affecting the transmission of the novel coronavirus. SiO2 and CB, as constituents of PM2.5 originating from desert dust and vehicle emissions, play a significant role in ocular health38.

SiO2 is typically present in the form of quartz or cristobalite and may be released into the air during sandstorms and construction activities19. In contrast, CB particles are produced during incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, including those used for vehicle exhaust and power generation20. The change of ACE2 expression on the ocular surface differed depending on the type of NPs. Our findings suggest that exposure to SiO2 may potentially increase the risk of contracting COVID-19 through the ocular surface, while exposure to CB may potentially reduce this risk. However, these observations are based on indirect evidence, and further research is needed to establish definitive conclusions.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Keratinocyte-serum free medium (K-SFM), keratinocyte supplements containing human recombinant epidermal growth factor and bovine pituitary extract, phenol red–free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium, 0.05% trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, fetal bovine serum, 1 × phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS), penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/mL), and radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer (no. 89901) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fibronectin was purchased from Corning (Corning, NY, USA). Rat tail collagen type I was obtained from Advanced BioMatrix (San Diego, CA, USA). Water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST)-8 cell viability kit was purchased from DoGen Bio (Seoul, Korea). Anti-ACE2 (#ab108282), anti-TMPRSS2 (#ab 214461).The AngII antibody (#NB100-62346) was obtained from Novus Biologicals (Novusbio, UK). The β-actin (#5125) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The ELISA kits for TNF-α (#BMS223-4), IL-6 (#BMS213INST), and IL-1β (#KAC121) were purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, USA).

Particle preparation

Particle SiO2 (#637238, size 10-20 nm) from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and CB (#Printex55, size 25nm) from Orion Engineered Carbons (Piscataway, NJ, USA) were used to manufacture the suspension. All particle samples were weighed using a high-precision microbalance, and suspended in sterile PBS at a concentration of 10 mg/mL. Before being diluted in cell culture media, the suspensions were sonicated four times intermittently (5 minutes every 10 minutes) in a bath sonicator. The suspensions were then sonicated three more times for 20 seconds within 5 minutes before their experimental use to minimize aggregation and ensure homogeneity. The concentration used for the eye drops in rats was 2 mg/ml.

Cell culture and treatment

HCECs (ATCC no. CRL-11516™, 2.040 pRSV-T) and HCjECs (KCLB no. 30052, clone 1-5c-4 [Wong-Kilbourne derivative (D) of Chang conjunctiva]) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA) and Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Seoul, Korea), respectively. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The HCECs were cultured in Keratinocyte-SFM (K-SFM) supplemented with 0.05 mg/mL of bovine pituitary extract, 5 ng/mL of human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF), 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The HCjECs were maintained in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. In the experiments, HCECs (2 × 105 cells/mL) and HCjECs (2 × 105 cells/mL) were seeded in 96-well, 24-well, and six-well plates with 100 µL, 500 µL, and 2500 µL of culture medium, respectively. The cells were incubated for 24 hours to reach 90% confluency and treated with NPs at the specified concentration. The cellular responses were examined after the initial exposure, and the results were compared with those of untreated cells (control group).

Cytotoxicity tests

Cell viability was assessed using a WST-8 assay kit. The cells were treated with various concentrations of NPs (0, 50, 100, or 200 μg/mL), or left untreated for 24 hours. Next, the WST-8 reagent (DoGen Bio, Seoul, Korea) was added to each well and incubated for two hours. The colored supernatant was then measured at 450 nm. The results were expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Protein extraction and western blotting

The cells were seeded in six-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. After treatment with 100 µg/mL SiO2 or CB for 24 h, the cells were lysed on ice for 30 min in a radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation. The protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid method. The protein lysate was mixed with loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against ACE2 , TMPRSS2, AngII, and β-actin. β-actin was used as an internal control. The intensity of the immunoreactive bands was analyzed using ImageJ. The sources and dosages of all antibodies are listed in Table 1.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ELISA assays were performed to measure the secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. The cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates and treated with SiO2 and carbon black particles for 24 hours after reaching 90% confluency. After centrifugation and removal of cell debris, the supernatant was collected and used for ELISA assays with TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β kits purchased from Invitrogen to determine their expression levels. The ELISA kits used are listed in Table 2.

Animal model of ocular surface injury

This study used 54 male Sprague-Dawley rats with an inbred strain. The rats weighed between 250 and 300 g and were 6-8 weeks old. The rats were randomly divided into the following three groups:control group (n = 18), SiO2 group (n = 18), and CB group (n = 18). All animal procedures were performed according to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research (Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Animal Policy). Approval for this animal study was obtained from the Korea University Animal Institutional Review Board in Seoul, South Korea(Approval number of the animal experiment protocol: KOREA-2022-0095). The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org)

The SiO2 and CB particles were dissolved in normal saline (2 mg/mL) to prepare the ocular surface injury model. Normal saline was used for the control group. The experiment was conducted on the right eye of each rat. Each rat in the respective group was topically administered 4 μL of eye drops. The eye drops were applied twice a day (at 9:00 A.M. and 6:00 P.M.) for 10 days.

Ocular surface Rose Bengal staining

At the end of the 10th day, after the final eye drop application, a slit-lamp examination was performed under general anesthesia. General anesthesia was induced through an intramuscular injection of alfaxalone (3 mg/100 g body weight; Jurox Pty. Ltd., Rutherford, Australia) and xylazine hydrochloride (Rompun 2%, 1 mg/100 g body weight; Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany).

The Rose Bengal staining score of the ocular surface (n=6 per group) was graded using the Rose Bengal staining strips (Akriti, Hyderabad, India) on a scale of 0-3 and evaluated on the corneal upper, lower, central, temporal and nasal conjunctiva according to the method proposed by Shimmura et al.39.

Preparation of tissue lysates for western blot analysis

To analyze the expression levels of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and AngII in the corneal or conjunctival tissues, we sacrificed Rats after SiO2 and CB exposure. Experienced ophthalmologists collected the corneal and conjunctival tissues under a microscope. The collected tissue samples were placed into a radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer for subsequent preparation of tissue lysates. The tissue samples were homogenized with RIPA buffer on ice, and then centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was stored at -80°C until the western blot analysis. The sources and dosages of all antibodies are listed in Table 1.

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD) and plotted using Prism software. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze statistical differences between the two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was used for multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study and are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the data providers.

References

Wu, Z. & McGoogan, J. M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 323, 1239–1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648 (2020).

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395, 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in patients out of Wuhan from China: A case control study. Bmc Infect Dis 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05897-z (2021).

Mullol, J. et al. The loss of smell and taste in the COVID-19 outbreak: A tale of many countries. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 20, 61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-020-00961-1 (2020).

Zaim, S., Chong, J. H., Sankaranarayanan, V. & Harky, A. COVID-19 and multiorgan response. Curr Prob Cardiology 45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2020.100618 (2020).

Zhou, L. et al. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are expressed on the human ocular surface, suggesting susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ocul Surf 18, 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2020.06.007 (2020).

Zhou, P. et al. Addendum: A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 588, E6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2951-z (2020).

Ou, X. et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun 11, 1620. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15562-9 (2020).

Strope, J. D., Pharm, D. C. & Figg, W. D. TMPRSS2: Potential biomarker for COVID-19 outcomes. J Clin Pharmacol 60, 801–807. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.1641 (2020).

Burrell, L. M., Johnston, C. I., Tikellis, C. & Cooper, M. E. ACE2, a new regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. Trends Endocrin Met 15, 166–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2004.03.001 (2004).

Hamming, I. et al. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol 203, 631-637, https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1570 (2004).

Willcox, M. D. P., Walsh, K., Nichols, J. J., Morgan, P. B. & Jones, L. W. The ocular surface, coronaviruses and COVID-19. Clin Exp Optom 103, 418–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/cxo.13088 (2020).

Ferrario, C. M. Myocardial infarction increases ACE2 expression in rat and humans. Eur Heart J 26, 1141. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi256 (2005) (author reply 1141-1143).

Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 (2020).

Botto, L. et al. Effects of PM2.5 exposure on the ACE/ACE2 pathway: Possible implication in COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054393 (2023).

Kim, J. H. et al. Diesel particulate matter 2.5 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and upregulation of SARS-CoV-2 receptor during human pluripotent stem cell-derived alveolar organoid development. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228410 (2020).

Huang, C. C., Chen, B. Y., Pan, S. C., Hoe, Y. L. & Guo, Y. L. Prenatal exposure to PM2.5 and congenital heart diseases in Taiwan. Sci Total Environ 655, 880–886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.284 (2019).

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D. & Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 525, 367–371. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15371 (2015).

Liu, H. B. et al. Distribution and sources of PM2.5-bound free silica in the atmosphere of hyper-arid regions in Hotan, North-West China. Sci Total Environ 810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152368 (2022).

Janssen, N. A. H. et al. Black carbon as an additional indicator of the adverse health effects of airborne particles compared with PM10 and PM2.5. Environ Health Persp 119, 1691–1699. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1003369 (2011).

Han, J. Y., Kang, B., Eom, Y., Kim, H. M. & Song, J. S. Comparing the effects of particulate matter on the ocular surfaces of normal eyes and a dry eye rat model. Cornea 36, 605–610. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000001171 (2017).

Li, X. et al. The protective effect of an eye wash solution on the ocular surface damage induced by airborne carbon black exposure. Cornea 39, 1040–1047. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000002304 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Comparison of cytotoxicity effects induced by four different types of nanoparticles in human corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells. Sci Rep 12, 155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04199-3 (2022).

Aggarwal, K. et al. Ocular surface manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 15, e0241661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241661 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. Ocular manifestations and clinical characteristics of 535 cases of COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: A cross‐sectional study. Acta Ophthalmologica 98. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14472 (2020).

Xia, J., Tong, J., Liu, M., Shen, Y. & Guo, D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol 92, 589–594. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25725 (2020).

Nagata, N., Iwata-Yoshikawa, N. & Taguchi, F. Studies of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus pathology in human cases and animal models. Vet Pathol 47, 881–892. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985810378760 (2010).

Taal, M. W. & Brenner, B. M. Renoprotective benefits of RAS inhibition: from ACEI to angiotensin II antagonists. Kidney Int 57, 1803–1817. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00031.x (2000).

Keidar, S., Kaplan, M. & Gamliel-Lazarovich, A. ACE2 of the heart: From angiotensin I to angiotensin (1–7). Cardiovasc Res 73, 463–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.09.006 (2007).

Donoghue, M. et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1–9. Circ Res 87, E1-9. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.res.87.5.e1 (2000).

Sui, Z. et al. The cytotoxicity of PM(2.5) and its effect on the secretome of normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 29, 75966–75977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-20726-9 (2022).

Ferrario, C. M. & Varagic, J. The ANG-(1–7)/ACE2/mas axis in the regulation of nephron function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298, F1297-1305. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00110.2010 (2010).

Leonardi, A., Rosani, U. & Brun, P. Ocular surface expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptors. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 28, 735–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2020.1772314 (2020).

Lu, C. W., Liu, X. F. & Jia, Z. F. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. Lancet 395, e39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30313-5 (2020).

Li, J. O., Lam, D. S. C., Chen, Y. & Ting, D. S. W. Novel Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): The importance of recognising possible early ocular manifestation and using protective eyewear. Br J Ophthalmol 104, 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-315994 (2020).

Li, S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is expressed in human conjunctival tissue, especially in diseased conjunctival tissue. Ocul Surf 19, 249–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2020.09.010 (2021).

Collin, J. et al. Co-expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the superficial adult human conjunctival, limbal and corneal epithelium suggests an additional route of entry via the ocular surface. Ocul Surf 19, 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2020.05.013 (2021).

Zhu, S. et al. Safety assessment of nanomaterials to eyes: An important but neglected issue. Adv Sci (Weinh) 6, 1802289. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201802289 (2019).

Shimmura, S. et al. Sodium hyaluronate eyedrops in the treatment of dry eyes. Brit J Ophthalmol 79, 1007–1011. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.79.11.1007 (1995).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through the Core Technology Development Project for Environmental Diseases Prevention and Management funded by the Korean Ministry of Environment (MOE) (2022003310001) and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1F1A1047497). The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS. Song contributed to the design, preparation, and analysis of the work; B. Kang, Y. Eom, DH. Kim, XZ li, and XM. Li interpreted the data and participated in the discussion. In addition, XM. Li and XZ li conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All rats were provided by the Korea University Animal Research Center and carried out under the guidance and approval of the Animal Ethics Committee of Korea University(Approval number of the animal experiment protocol: (KOREA-2022-0095).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Li, X., Kang, B. et al. Effect of carbon black and silicon dioxide nanoparticle exposure on corona receptor ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression in the ocular surface. Sci Rep 14, 27023 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78518-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78518-9