Abstract

This study explored the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and monkeypox co-infection, identifying candidate hub genes and potential drugs using bioinformatics and machine learning. Datasets for HIV (GSE 37250) and monkeypox (GSE 24125) were obtained from the GEO database. Common differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in co-infection were identified by intersecting DEGs from monkeypox datasets with genes from key HIV modules screened using Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA). After gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis and construction of protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, candidate hub genes were further screened based on machine learning algorithms. Transcriptional factors (TFs) and miRNA-candidate hub gene networks were constructed to understand regulatory mechanisms and protein-drug interactions to identify potential therapeutic drugs. Seven candidate hub genes—MX2, ADAR, POLR2H, RPL5, IFI16, IFIT2, and RPS5—were identified. TFs and miRNAs associated with these hub genes, playing a key role in regulating viral infection and inflammation due to the activation of antiviral innate immunity, were also identified through network analysis. Potential therapeutic drugs were screened based on these hub genes: AZT, a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, suppressed viral replication in HIV and monkeypox co-infection, while mefloquine inhibited inflammation due to the activation of antiviral innate immunity. In conclusion, the study identified candidate hub genes, their transcriptional regulation, signaling pathways, and small-molecule drugs in HIV and monkeypox co-infection, contributing to understanding the pathogenesis of HIV and monkeypox co-infection and informing precise therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Monkeypox is a zoonotic disease caused by the monkeypox virus, which was first identified in 1970 in Western Africa and was considered an endemic disease1. Monkeypox reemerged in Nigeria in 2017, and cases of travelers’ monkeypox were subsequently exported to other parts of the world, with an epidemic breaking out globally in 20222. The World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines indicate that fever, headache, back pain, muscle aches, lack of energy, and lymphadenopathy are common symptoms and signs in the initial phase, followed by the appearance of a rash over a period of 2 to 3 weeks in the second phase3. Despite the mild disease course due to smallpox vaccination among populations over 40–50 years of age, most of the reported severe cases or deaths occurred among immunosuppressed individuals, especially among poorly controlled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals4, indicating that it is necessary to increase awareness of screening and diagnosis of monkeypox infection among HIV-infected populations.

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) is a chronic infectious disease caused by HIV, which depletes the immune system, especially CD4 + helper T cells, causing opportunistic infections and malignancies when CD4 + T cells decrease to less than 200 cells/uL. The WHO reported5 that HIV remains a major global public health problem, affecting 40.4 million people worldwide. In 2022, 630 thousand people died from HIV-associated comorbidities, and 1.3 million people acquired HIV.

Current literature reports that1 the monkeypox virus tends to cause more severe disease in HIV-infected patients. This suggests a need to explore the molecular mechanisms of HIV and monkeypox co-infection and to search for potential small-molecule therapeutics for these patients.

In this study, we identified hub genes involved in viral infection and regulation of innate antiviral immunity in HIV and monkeypox co-infections using bioinformatics analysis, machine learning algorithms, lasso regression, and random forest. We further analyzed protein-drug interactions with these hub genes to identify potential small-molecule therapeutic compounds for the treatment of HIV and monkeypox co-infection.

Methods

Study design

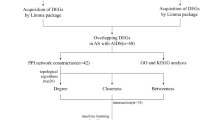

The HIV (GEO accession ID: GSE 37250) and monkeypox (GEO accession ID: GSE 24125) datasets were downloaded from the GEO database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened in the monkeypox dataset using the “limma” R package, while key modules were uncovered in the HIV dataset based on Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), in which core genes were screened in the most significant key modules. Common DEGs in HIV and monkeypox co-infection were identified based on the intersection with Venn analysis between DEG in monkeypox datasets and core genes in the HIV dataset screened with WGCNA.

We further conducted functional enrichment analysis, including gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses, and constructed a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of the intersected DEGs, in which PPI network analysis was carried out to identify node genes with mutual connections. Then, potential candidate hub genes were further screened based on machine learning algorithms, including lasso regression and random forest.

To understand the regulatory mechanisms of potential candidate hub genes at the transcriptional level, the associations among transcriptional factors (TFs), miRNAs, and candidate hub genes were further explored.

Finally, protein–drug interactions to identify potential small molecular therapeutic compounds for the treatment of HIV and monkeypox co-infection were screened in this study (Fig. 1).

Data sources

To determine the common molecular mechanism between monkeypox and HIV infection, RNA-Sequencing datasets were downloaded from the GEO database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), in which one monkeypox dataset (GEO accession ID: GSE24125) consisted of 16 monkeypox-infected samples and 20 healthy control samples, while one HIV dataset (GEO accession ID: GSE37250) consisted of 274 HIV-infected whole-blood samples and 263 healthy control samples.

The representative GEO data sets for HIV (GSE 37250) and monkeypox (GSE 24125) were selected for this study. Background data in GSE 37,2506 indicated that adults were recruited from Cape Town, South Africa (n = 300) and Karonga, Malawi (n = 237), with relatively low CD4 cells/uL, who were prone to complications from opportunistic infections, including monkeypox. Background data in GSE 24,1257 included 16 monkeypox-positive patients and 20 controls, with bioinformatic data provided from primary human macrophages infected with the monkeypox virus.

Differentially expressed genes screening

DEGs screening for the monkeypox infection was carried out in the above-mentioned dataset (GSE24125), and DEGs were identified using the “limma” R package (https://www.r-project.org/ ) (R version 12.0) with |Log2 Fold Change| ≥ 0.5. A false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p-value of less than 0.05 was treated as a criterion for identifying the DEGs for monkeypox infection.

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis and Module Selection

WGCNA is a bioinformatics tool used to study gene expression patterns in different samples; it can cluster genes with similar gene expression patterns, form modules, further identify the complex relationship between related modules and specific characteristics or phenotypes, and identify intramodular hub genes8,9,10. Co-expression gene network was conducted based on the “WGCNA” R package for all genes in HIV infection and normal samples. The expression profiles in the top 50% variance and median absolute deviation (MAD) greater than 0.01 were filtered for further study. Then, an appropriate soft threshold was determined based on the “pickSoftThreshold” function, an adjacency matrix was clustered with soft threshold parameters, and the key modules were determined.

Common DEGs between monkeypox and HIV infection were obtained based on the intersection of DEGs in monkeypox infection and the most significant module genes in HIV infection using a Venn diagram.

Functional enrichment analysis

Understanding the functional enrichment of intersecting genes between DEGs in monkeypox infection and the core genes of WGCNA modules in HIV infection helped us comprehend the molecular biological mechanisms of HIV and monkeypox co-infection. GO and KEGG11,12,13 (https://www.kegg.jp) analyses were conducted for functional enrichment of common intersected genes using the “clusterProfiler” package in R software. A p-value of less than 0.1 was used to quantify the listed gene functions and pathways of common DEGs.

Analysis of protein-protein interaction and network construction

Understanding the interactions among proteins expressed by common intersecting genes between DEGs in monkeypox infection and core genes of WGCNA modules in HIV infection, as well as other proteins, helped us understand their functions. The PPI network was constructed using STRING (https://www.string-db.org/) (version 12.0) with a combined score of > 0.4 and was analyzed and visualized using Cytoscape software (https://cytoscape.org/) (version 3.9.1). Node genes were identified using the CytoNCA plug-in and selected for further filtering of potential hub genes using machine learning.

Machine learning for filtering potential candidate hub genes

A machine learning algorithm was applied to filter potential hub genes, which helped construct TF-common DEGs interactions and TF-miRNA regulatory networks, and to predict potential small-molecule therapeutic compounds. LASSO regression is a popular algorithm that is ordinarily used in small samples and high-dimensional data. It has unique characteristics that penalize the absolute value of a regression coefficient, which helps improve the predictive accuracy and interpretability of a statistical model to screen the best predictive variables. The R package “glmnet” was used to conduct LASSO regression. Random forest is another machine learning algorithm used to predict potential hub genes with better accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity based on the “randomForest” R package. Candidate hub genes were identified based on the intersection of results from LASSO regression and random forest analyses. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to evaluate the potential ability of hub genes to predict HIV and monkeypox virus infections14,15.

Construction of TF-hub genes interaction and TF-miRNA regulatory network

Transcription factors (TFs) bind to the promoters of specific genes to regulate the expression of target genes. The TF-hub gene interaction network was constructed using NetworkAnalyst (http://www.networkanalyst.ca) (version 3.0), which helped to evaluate the regulation of TFs on the expression and signaling pathways of hub genes. In this study, ENCODE was used to identify the TFs of hub genes and to construct a TF-gene interaction network, which was visualized using Cytoscape.

MiRNAs are post-transcriptional regulatory non-coding RNA that degrade or inhibit target mRNA expression. In this study, a hub gene-miRNA interaction network was constructed using TarBase v8.0, and its regulatory network was constructed using NetworkAnalyst 3.0. This approach helped elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of candidate hub gene expression in HIV and monkeypox co-infection, which was visualized using Cytoscape.

Prediction of therapeutic small molecular compounds

Protein-drug interaction and potential small molecular therapeutic compounds were evaluated based on candidate hub genes that were shared in HIV and monkeypox co-infection using the “enrichR” Drug Signatures Database (DSigDB) function in R package, which connected drugs or small molecular therapeutic compounds to specific target genes. The predicted therapeutic compounds were sorted by adjusted p-values, in which a p-value less than 0.01 was treated as statistically significant.

Molecular docking of small molecular compounds and target proteins

Molecular docking was used to identify new small-molecule compounds based on the in silico prediction of interactions between drugs and target proteins. Three-dimensional structure of small molecular compounds based on candidate hub genes expression in HIV and monkeypox co-infection was identified in PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), while target proteins of monkeypox infection included H1 phosphatase16, Thymidylate kinase17,18, Topoisomerase-118 and IMP-Dehydrogenase19, and their crystal structures were obtained from the Uniprot database(https://www.uniprot.org/). Molecular docking was conducted between identified small molecular compounds based on candidate hub genes expression and target proteins of monkeypox infection using AutoDock software(http://autodock.scripps.edu/)(version 1.5.7), with 3D visualization carried out using Pymol software (https://www.pymol.org/ )(version 2.4.0).

Results

Identification of DEGs of monkeypox infection

To study the interaction between monkeypox and HIV, DEGs were identified in the monkeypox datasets using the “limma” R package with |Log2 Fold Change| ≥ 0.5. In the monkeypox dataset GSE24125, 2996 DEGs were identified, including 90 upregulated and 2906 downregulated genes (Fig. 2A).

A Volcano plots exhibiting DEGs of monkeypox infection. B and H WGCNA analysis in HIV and identification of key modules. (B) β = 8 was selected as the soft threshold with the combined analysis of scale independence and average connectivity; (C) Systematic clustering tree of samples; (D) Gene co-expression modules represented by different colors; (E) Heatmap of the association between modules and HIV; (F) Correlation plot between module membership and gene significance of genes included in the magenta module; (G) Correlation plot between module membership and gene significance of genes included in the pink module; (H) Correlation plot between module membership and gene significance of genes included in the salmon module. (I) Venn diagram showing the intersection of DEGs from monkeypox identified via Limma with the module genes from HIV in the magenta, salmon, and pink modules identified via WGCNA, resulting in 25 common genes.

WGCNA analysis and identification of key modules

In the HIV dataset, the probe with the highest average value was selected as the only probe of the symbol. Subsequently, 4059 genes were screened based on the top 50% of the median absolute deviation (MAD) and a threshold greater than 0.01. All samples that met the standards were included in the analysis after quality evaluation. Soft threshold power β was set to 8, and the scale-free R2 reached 0.9 (Fig. 2B). The minimum number of genes for each network module was set to 30, and the threshold for merging modules was set to 0.25. A clustering tree diagram of genes was constructed based on the differences in topology overlap and specified module colors (Fig. 2C and D), resulting in 16 gene co-expressed modules (GCMs) for the HIV groups, as shown in Fig. 2E using different colors. Each row represents one module and each cell indicates correlation and p-value. The MEmagenta (correlation coefficient = 0.43, p = 5E-12, 94 genes), MEpink (correlation coefficient = 0.31, p = 1E-06, 121 genes), and MEsalmon (correlation coefficient = 0.28, p = 1E-06, 61 genes) modules exhibited the highest correlation with HIV and were selected for subsequent analysis. Finally, we calculated the correlation between module membership and gene significance in the magenta (correlation coefficient = 0.6, p = 1.6E-10) (Fig. 2F), pink (correlation coefficient = 0.25, p = 0.0057) (Fig. 2G), and salmon (correlation coefficient = 0.56, p = 2.7E-06) (Fig. 2H) modules.

Identification of common DEGs in HIV and monkeypox co-infection

The intersection of DEGs in monkeypox and core genes in key WGCNA modules of HIV was used to determine whether the DEGs in monkeypox infection were related to those in HIV infection, and results indicated that 25 common genes were found based on the intersection of 276 genes obtained from WGCNA in HIV infection and 1493 DEGs in monkeypox (Fig. 2I).

Gene enrichment analysis of common DEGs in HIV and monkeypox co-infection

GO analysis indicated, for these 25 common DEGs, that biological processes (BPs) were mainly enriched in “defense response to virus” and “defense response to symbolt”. Cellular components (CC) were enriched in the “cytosolic ribosome”, “ribosomal bundle”, and “ribosome”. Molecular Function (MF) analysis was mainly enriched in “double stranded RNA binding” and “adenosine deaminase activity” (Fig. 3A). KEGG analysis indicated that these common DEGs were mainly enriched in “Coronavirus disease COVID-19”, “Measle”, “Influenza A”, “Hepatitis C”, and “Ribosome” (Fig. 3B). The results of the enrichment analysis indicated that the common DEGs in HIV and monkeypox co-infection were mainly related to the synthesis of virus-associated polypeptides via ribosomes and defense responses to viruses.

Enrichment analysis of common genes for HIV and monkeypox co-infection. (A) GO analysis (BP, CC, and MF) of 25 common genes in HIV and monkeypox co-infection; (B) KEGG analysis of 25 common genes in HIV and monkeypox co-infection (https://www.kegg.jp). (C) PPI network showing the interaction of 14 genes, visualized using the CytoNCA plug-in.

Construction of PPI network and identification of node genes

PPI was explored based on STRING analysis for the common 25 DEGs in HIV and monkeypox co-infection. Figure 3C shows the interaction of common DEGs in HIV and monkeypox co-infection. Except for 9 DEGs without interactions, 14 node genes were determined based on the results of the PPI network in Cytoscape, including MX1, MX2, OAS2, ADAR, ADARB1, POLR2H, RPL5, IFI16, IFIT2, RPS5, RPS12, TRAF3IP3, BIRC3, and EIF3D, which underwent further screening for candidate hub genes based on machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning identified potential candidate hub genes in HIV and monkeypox co-infection

LASSO regression and RF machine learning algorithms were used to identify potential candidate hub genes in HIV and monkeypox co-infection. Among the 14 node genes, 11 key genes were identified based on the LASSO regression algorithm (Fig. 4A and B). In the RF machine learning algorithm, the importance of node genes was calculated and ranked, and the top 10 genes were selected (Fig. 4C and D). Seven potential candidate hub genes, including MX2, ADAR, POLR2H, RPL5, IFI16, IFIT2, and RPS5, in HIV and monkeypox co-infection were identified based on the intersection between 11 key genes identified in the LASSO regression and the top 10 genes calculated in RF machine learning (Fig. 4E). The areas under the ROC curve for the 7 hub genes were 0.898 (MX2), 0.867 (ADAR), 0.88 (POLR2H), 0.873 (RPL5), 0.881 (IFI16), 0.769 (IFIT2) and 0.737 (RPS5), separately (Fig. 4F).

Machine learning in screening candidate hub genes for HIV and monkeypox co-infection. (A, B) Key genes screening in the Lasso model; the number of key genes (n = 11) corresponding to the λ-se was the most suitable in HIV and monkeypox co-infection. (C, D) Top 10 genes selected based on the random forest algorithm; (E) Venn diagram showing that 7 candidate hub genes were identified via the above two algorithms. (F) The ROC curve of each hub gene (MX2, ADAR, POLR2H, RPL5, IFI16, IFIT2 and RPS5).

Construction of transcriptional regulatory network

To understand the transcriptional regulation of potential candidate hub genes in HIV and monkeypox co-infection, a transcriptional regulatory network was constructed to decode TFs and miRNAs. A potential candidate hub gene-TF interaction network was constructed using ENCODE (Fig. 5A & Table S1). Among the 7 potential candidate hub genes in HIV and monkeypox co-infection, RPS5, POLR2H, RPL5, ADAR, and IFI16 were regulated by more TFs in the hub gene-TF interaction network. TFs such as ZNF639, FOXA3, ZNF24, GTF2E2, TRIM28, EED, and KLF1 were more commonly associated with these genes compared to others.

A pivotal hub gene-miRNA interaction network was constructed using TarBase v8.0 (Fig. 5B & Table S2). Among the seven pivotal hub genes, ADAR, IFIT2, IFI16, POLR2H, RPL5, and MX2 were regulated by more miRNAs in the hub gene-miRNA interaction network, in which hsa-mir-129-2-3p, hsa-mir-1-5p, hsa-mir-155-5p, and hsa-mir-16-5p were more common than others.

Identification of candidate small molecular compounds

Ten candidate small molecule compounds were identified in the PubChem database based on 7 candidate hub genes (Table 1), and the druggability/ADME/Toxicity of the leads are presented in Table S3. Molecular docking was conducted between these compounds and target proteins of monkeypox, including H1 phosphatase16, Thymidylate kinase17,18, Topoisomerase-118, and IMP-Dehydrogenase19, and results of binding sites and energy for key drug targets based on AutoDock calculations were described in detail (Table 1). 3’-Azido-3’-deoxythymidine (Zidovudine, AZT) (Fig. 6A and H) and mefloquine (Fig. 6I and P) presented good binding sites and energy in target proteins. The details of the protein structure are listed in Table S4.

Molecular docking patterns between AZT and H1 phosphatase (A, B), IMP-Dehydrogenase (C, D); Thymidylate kinase (E, F); and Topoisomerase-1 (G, H), respectively. Molecular docking patterns between mefloquine and H1 phosphatase (I, J), IMP-Dehydrogenase (K, L); Thymidylate kinase (M, N); and Topoisomerase-1 (O, P), respectively. The interaction sites of amino acids between monkeypox-associated drugs and small molecules targeted by the monkeypox virus and distances between the binding sites of different amino acids on small molecules and monkeypox-associated drugs (yellow dotted line).

Discussion

A recent study indicated that HIV-infected patients are more prone to monkeypox virus infection compared to HIV-negative individuals. However, the molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic small molecular compounds involved in this co-infection remain unclear. This study aimed to elucidate the correlation between monkeypox and HIV infection, explore the pathogenesis of this co-infection, and screen for potential therapeutic small-molecule compounds. We found that candidate hub genes were involved in HIV and monkeypox co-infections, which play key roles in the translation of virus-associated polypeptides for viral infections and in the activation and regulation of antiviral innate immunity. TFs and the microRNA regulatory network of these candidate hub genes played a key role in regulating viral infection and inflammation due to the activation of antiviral innate immunity. Potential therapeutic small molecular compounds were screened based on these hub genes. AZT, a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, was found to suppress HIV and monkeypox co-infected viral replication20, while mefloquine inhibited inflammation21 due to the activation of antiviral innate immunity caused by the co-infection.

In the HIV dataset, DEGs were screened using the “limma” package, yielding 155 genes. WGCNA was then employed to cluster genes with similar expression patterns, form modules, uncover complex relationships between related modules and specific features or phenotypes, and identify central genes within modules8,9. WGCNA identified 276 HIV-related DEGs, which were intersected with DEGs from the monkeypox dataset to reveal common DEGs between HIV and monkeypox co-infection.

Enrichment analysis of the functions and signaling pathways of the DEGs helped elucidate the molecular mechanisms of these intracellular DEGs. In this study, 25 DEGs were identified based on intersection analysis between WGCNA analysis in the HIV dataset and DEGs in the monkeypox dataset. GO and KEGG analyses were conducted to explore the relationship between HIV and monkeypox infection. GO analysis was performed for BP, CC, and MF. BP analysis of these DEGs revealed that they were mainly enriched in the defense response to viruses, defense response to symbionts, and response to viruses. Recent studies have indicated that22 immunosuppression increased viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, including monkeypox infection, which induces a defense immune response against these pathogens in vivo. CC analysis of these DEGs showed enrichment in the cytosolic ribosome. The most common KEGG pathways included coronavirus disease-COVID-19, measles, influenza A, hepatitis C, and ribosome, indicating that SARS-CoV-2, measles, influenza A, and hepatitis C viruses were more likely to infect HIV and monkeypox co-infected patients due to their immunosuppressed status. This suggests that these virus-associated polypeptides were synthesized via the ribosome, which is crucial for viral infection. The MF results showed that these DEGs were mainly enriched for double-stranded RNA binding, adenosine deaminase activity, and cysteine-type endopeptidase inhibitor activity involved in apoptosis. Immunosuppression can lead to opportunistic pathogenic infections, including double-stranded RNA viruses. Adenosine deaminase23, an RNA editing enzyme, can catalyze the deamination of adenosine (A) to produce inosine (I) in double-stranded RNA, known as A-to-I RNA editing. This process presents important biological significance, including the production of interferon to help clear viral infections.

In order to reduce the influence of overfitting and improve the quality of DEGs, we used two machine learning algorithms, LASSO regression analysis and random forest, to identify candidate hub genes. Seven hub genes were identified, including MX2, ADAR, POLR2H, RPL5, IFI16, IFIT2, and RPS5. ROC analysis indicated a higher AUC for these genes to predict HIV and monkeypox infections, indicating that these candidate hub genes could be further used to construct a transcriptional-level regulatory network and identify candidate drugs based on gene-drug enrichment analysis.

We found that two candidate hub genes, RPS524 and RPL525, played key roles in viral infections, whereas other candidate hub genes, including ADAR23, IFI1626, IFIT227 and MX228, were involved in the activation and regulation of antiviral innate immunity.

RPS524 and RPL525 are ribosomal proteins that interact with RNA and play key roles in the translation of virus-associated polypeptides for viral infections. ADAR23, as an RNA editing enzyme, exerted RNA editing activity as an intracellular innate immune defense mechanism to inhibit HIV replication, while ADAR also modulated gene expression of the monkeypox virus based on observations of TC→TT editing for successful immune evasions, which indicated that ADAR was involved in the regulation of antiviral innate immunity23. IFI1626 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular viruses that directly senses viral RNA to enhance RIG-I transcription and activates the RIG-I signaling pathway to restrict viral replication29. Antiviral innate immunity is activated after viral infection, and cytokines, including interferons, are induced in vivo, which further induce interferon-stimulating genes (ISGs), including IFIT227 and MX228, to protect against viral infections. POLR2H participates in RNA splicing and protein translation and interacts with the F3 protein encoded by the monkeypox virus, indicating that POLR2H is related to monkeypox infection in vitro30.

To understand the regulatory mechanisms of hub genes at the transcriptional level, the associations between TFs, miRNAs, and hub genes were further explored. MicroRNA, as a post-transcriptional gene silencing mechanism, regulated specific target gene function via incomplete complementary pairing at 3’ UTR of target genes, which was involved in various biological functions, including activation or suppression of inflammation. TFs, as transactivation factors, bind to the cis-acting elements of target genes to regulate their expression, which is involved in the regulation of various biological processes. In this study, we found that the regulatory relationships between cancer hub genes, TFs (ZNF639, FOXA3, ZNF24, GTF2E2, TRIM28, EED, and KLF1), and miRNAs (hsa-mir-129-2-3p, hsa-mir-1-5p, hsa-mir-155-5p, and hsa-mir-16-5p) play important roles in HIV and monkeypox co-infection.

We found that the TFs and miRNA regulatory networks of these hub genes play key roles in regulating viral infection and inflammation induced by antiviral innate immunity. ZNF639 stimulates HIV transcriptional elongation31 and regulates viral transcription in vivo32, ZNF24 is a TF that transactivates inflammatory gene expression once innate immunity is activated33. FOXA3 inhibits innate antiviral immunity and contributes to the susceptibility to viral infections34. GTF2E2, a novel antiretroviral target, is required for HIV replication35. TRIM28 SUMOylates and stabilizes NLRP3 to facilitate inflammasome activations36 and induction of chronic inflammation. Human polycomb group EED protein negatively affected HIV-1 assembly and release37. KLF1 is associated with pathogenic infections38, indicating that opportunistic infections are prone to occur among immunosuppressed HIV and monkeypox co-infected patients. hsa-mir-155-5p enhances innate antiviral immunity and inhibits viral infection39, while hsa-mir-16-5p exerts anti-inflammatory effects by downregulating the NLRP3 inflammasome40, indicating that these two miRNAs are involved in the regulation of innate immunity. Other miRNAs involved in HIV and monkeypox co-infection should be further studied.

By screening the DSigDB database, potential small-molecule therapeutic compounds were identified using hub genes, with the top 10 potential small-molecule compounds identified. AZT, a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, was found to inhibit HIV viral replication. Additionally, Bhattacharjee et al.20 identified AZT as a potential drug repurposable drug against monkeypox based on proteome-based investigations. Mefloquine was found to inhibit Panx1 channels present in the plasma membrane, mediating paracrine and autocrine signaling21, which inhibited inflammation in vivo and contributed to a good prognosis in several inflammatory diseases, indicating that mefloquine could inhibit acute inflammation in HIV and monkeypox co-infection.

The four monkeypox target proteins, H1 phosphatase16, thymidylate kinase17,18, Topoisomerase-118, and IMP-dehydrogenase19 were identified from the published literature. Small drug molecules obtained from the hub genes interacted with the monkeypox target proteins, and the binding sites of the small drug molecules with the monkeypox target proteins were predicted, providing theoretical support for future experimental validation.

This study had some limitations. First, only one monkeypox dataset was collected, which provided only a few samples; hence, the results should be validated with additional samples. Second, the conclusions of this study were based on bioinformatics analysis; thus, hub genes and the screened small-molecule therapeutic compounds need to be validated through clinical trials. Third, potential biases in this study include information bias and confounding bias due to co-infections with other pathogens, variations in ART regimens, and differences in immune responses among individuals. Finally, the molecular mechanisms underlying HIV and monkeypox co-infection require further investigation.

Conclusion

In this study, candidate hub genes, their transcriptional regulation, associated signaling pathways, and small molecule compounds were identified in the context of HIV and monkeypox co-infection. These findings contribute to understanding the pathogenesis, including viral infections, regulation of antiviral innate immunity, and potential targeted therapies for HIV and monkeypox co-infections.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- AZT:3’:

-

Azido-3’-deoxythymidine

- BP:

-

biological process

- CC:

-

cellular component

- DEG:

-

Differentially expressed gene

- DSigDB:

-

Drug signatures database

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- GCM:

-

gene co-expressed module

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- HIV :

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- ISG:

-

interferon-stimulating gene

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- MAD:

-

median absolute deviation

- MF:

-

molecular function

- PPI:

-

protein-protein interaction

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- TF:

-

transcriptional factor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WGCNA:

-

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

References

Alakunle, E., Moens, U., Nchinda, G. & Okeke, M. I. Monkeypox virus in Nigeria: infection biology, epidemiology, and evolution. Viruses. 12, 1257 (2020).

Thornhill, J. P. et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries - April-June 2022. N Engl. J. Med. 387, 679–691 (2022).

World Health Organization. Clinical Management and Infection Prevention and Control for Monkeypox: Interim Rapid Response Guidance 1–76. (2022).

Mitjà, O. et al. Mpox in people with advanced HIV infection: a global case series. Lancet. 401, 939–949 (2023).

Kaforou, M. et al. Detection of tuberculosis in HIV-infected and -uninfected African adults using whole blood RNA expression signatures: A case-control study. PLOS Med. 10, e1001538 (2013).

Rubins, K. H., Hensley, L. E., Relman, D. A. & Brown, P. O. Stunned silence: Gene expression programs in human cells infected with monkeypox or vaccinia virus. PLOS ONE. 6, e15615 (2011).

Zhang, B. & Horvath, S. A general for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 4, Article17 (2005).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. W. G. C. N. A. An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 559 (2008).

Li, Z. et al. Identification and validation of prognostic markers for lung squamous cell carcinoma associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Oncol. 4254195 (2022). (2022).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592 (2023).

Lobo, J. M., Jiménez-Valverde, A. & Real, R. A. U. C. A misleading measure of the performance of predictive distribution models. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 17, 145–151. (2008).

Janssens, A. C. J. W. & Martens, F. K. Reflection on modern methods: Revisiting the area under the ROC curve. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49, 1397–1403 (2020).

Cui, W. et al. Crystal structure of monkeypox H1 phosphatase, an antiviral drug target. Protein Cell. 14, 469–472 (2023).

Ajmal, A. et al. Computer-assisted drug repurposing for thymidylate kinase drug target in monkeypox virus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1159389 (2023).

Srivastava, V. et al. Identification of FDA-approved drugs with triple targeting mode of action for the treatment of monkeypox: A high throughput virtual screening study. Mol. Divers., 1–15 (2023).

Hishiki, T. et al. Identification of IMP dehydrogenase as a potential target for anti-mpox virus agents. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0056623 (2023).

Bhattacharjee, A. et al. Proteome-based investigation identified potential drug Repurposable small molecules against monkeypox disease. Mol. Biotechnol., 1–15 (2022).

Rusiecka, O. M., Tournier, M., Molica, F. & Kwak, B. R. Pannexin1 channels-a potential therapeutic target in inflammation. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 10, 1020826 (2022).

Xiao, J. et al. Spectrums of opportunistic infections and malignancies in HIV-infected patients in tertiary care hospital, China. PLOS ONE. 8, e75915 (2013).

Ratcliff, J. & Simmonds, P. The roles of nucleic acid editing in adaptation of zoonotic viruses to humans. Curr. Opin. Virol. 60, 101326 (2023).

Qiu, L., Chao, W., Zhong, S. & Ren, A. J. Eukaryotic ribosomal protein S5 of the 40S subunit: Structure and function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 3386 (2023).

Dissanayaka Mudiyanselage, S. D., Qu, J., Tian, N., Jiang, J. & Wang, Y. Potato spindle tuber viroid RNA-templated transcription: Factors and regulation. Viruses. 10, 503 (2018).

Unterholzner, L. et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat. Immunol. 11, 997–1004 (2010).

Reich, N. C. A death-promoting role for ISG54/IFIT2. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 33, 199–205 (2013).

Betancor, G. You shall not pass: MX2 proteins are versatile viral inhibitors. Vaccines (Basel). 11, 930 (2023).

Jiang, Z. et al. IFI16 directly senses viral RNA and enhances RIG-I transcription and activation to restrict influenza virus infection. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 932–945 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Transcriptome and proteomic analysis of mpox virus F3L-expressing cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1354410 (2024).

Bruce, J. W. et al. ZASC1 stimulates HIV-1 transcription elongation by recruiting P-TEFb and TAT to the LTR promoter. PLOS Pathog. 9, e1003712 (2013).

Bruce, J. W., Bracken, M., Evans, E., Sherer, N. & Ahlquist, P. ZBTB2 represses HIV-1 transcription and is regulated by HIV-1 vpr and cellular DNA damage responses. PLOS Pathog. 17, e1009364 (2021).

Sun, R. L. et al. Resistance to lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxic shock in heterozygous Zfp191 gene-knockout mice. Genet. Mol. Res. 10, 3712–3721 (2011).

Chen, G. et al. Foxa3 induces goblet cell metaplasia and inhibits innate antiviral immunity. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 189, 301–313 (2014).

Dziuba, N. et al. Identification of cellular proteins required for replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 28, 1329–1339 (2012).

Qin, Y. et al. TRIM28 SUMOylates and stabilizes NLRP3 to facilitate inflammasome activation. Nat. Commun. 12, 4794 (2021).

Rakotobe, D. et al. Human polycomb group EED protein negatively affects HIV-1 assembly and release. Retrovirology. 4, 37 (2007).

Mikołajczyk, K., Kaczmarek, R. & Czerwiński, M. Can mutations in the gene encoding transcription factor EKLF (erythroid Krüppel-Like factor) protect us against infectious and parasitic diseases? Postepy Hig Med. Dosw (Online). 70, 1068–1086 (2016).

Rai, K. R. et al. MIR155HG plays a bivalent role in regulating innate antiviral immunity by encoding long noncoding RNA-155 and microRNA-155-5p. mBio 13, e0251022 (2022).

Li, B., Zhang, Z. & Fu, Y. Anti-inflammatory effects of artesunate on atherosclerosis via mir-16-5p and TXNIP regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Ann. Transl Med. 9, 1558 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged the work of statisticians for their statistical analysis in Ditan Hospital.

Funding

This work was supported by the 1) Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’ Ascent Plan (DFL20191802); 2) Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (ZYLX202126); and 3) Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (2020-2-2174). The funders played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: Jiang Xiao & Hongxin Zhao; Performed experiment: Jialu Li. Wrote the manuscript: Jialu Li. Collected and analyzed the data: Jialu Li, Yiwei Hao,Liang Wu, Hongyuan Liang, Liang Ni, Fang Wang, Sa Wang, Yujiao Duan, Qiuhua Xu, Jinjing Xiao, Di Yang, Guiju Gao, Yi Ding, Chengyu Gao.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Human Science Ethical Committee of Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with institutional requirements owing to the retrospective nature of the study. And all methods in the study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Acknowledgements.

We acknowledge the statisticians at Ditan Hospital for their assistance with statistical analysis.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Hao, Y., Wu, L. et al. Exploration of common pathogenesis and candidate hub genes between HIV and monkeypox co-infection using bioinformatics and machine learning. Sci Rep 14, 26701 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78540-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78540-x