Abstract

A Trailing Suction Hopper Dredger (TSHD) in the sailing process, excavating seabed sediment with the drag head and pumping it through the pipeline to the spoil hopper sedimentation. The spoil hopper sedimentation process, as a critical factor affecting the loading yield and efficiency of a dredger, is susceptible to the influence of different average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\). However, the soil type tends to change continuously during the loading process, making it difficult to obtain the \(d_{m}\) by measurement or calculation. In this paper, combined with the existing simplified one-dimensional sedimentation model and simulated loading data, the Bootstrap Particle Filter (BPF), Gaussian Particle Swarm Optimized Particle Filter (GPSO-PF), Assisted Particle Filter (APF), Continuous-Discrete Feedback Particle Filter based on the constant feedback gain approximation (CD-FPF-CG) and the Galerkin method feedback gain approximation (CD-FPF-GL) are applied in the numerical simulations for online estimation of important variables such as the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\), respectively. The simulations results show that the CD-FPF-CG has a higher numerical accuracy and efficiency than the BPF, GPSO-PF, APF and CD-FPF-GL. Therefore, the CD-FPF-CG is used to estimate the above important variables for the actual vessel and the initial value of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) for the CD-FPF-CG is determined via Simulated Annealing Multiple Population Genetic Algorithm (SAMPGA).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a type of hydraulic dredger, the Trailing Suction Hopper Dredger (TSHD) periodically performs loading operation by using the drag head to excavate seabed sediment in the course of sailing and conveying it through a pipeline to the cargo space, the so-called spoil hopper, for sedimentation. Compared with other types of dredgers, it has the unique advantages of being self-propelled, self-loading, self-unloading, deep dredging depth, flexibility and manoeuvrability, etc. The TSHD has been widely used in harbour and waterway construction and maintenance, reclamation, offshore mining and many other marine engineering applications.

In order to predict and optimize the dynamic behaviors and characteristics of the TSHD. It is necessary to develop the system mechanism models that can reflect the loading process of the TSHD, including drag head excavation, dredge pump pipeline transport and spoil hopper sedimentation. Among them, the spoil hopper sedimentation process, as a crucial component for enhancing the loading performance of the TSHD, is susceptible to the differences in dredging soils. Therefore, a timely understanding and knowledge about the type and nature of the in situ soil is essential to determine the soil-related parameters inherent in the sedimentation model. However, the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), as the crucial soil parameter in the hopper sedimentation process, changes continuously with excavation position of the dredger, which makes it hard to measure the \(d_{m}\) directly with measuring equipment or to derive it from empirical formulae. Alternatively, once a suitable sedimentation model has been selected, it can be combined with the measured data and appropriate estimation method to accurately and efficiently estimate the soil parameter including \(d_{m}\) and the co-dependent variables including sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) formed at the bottom of the spoil hopper.

Various researchers and scientists had developed static or dynamic models of the spoil hopper deposition process. As early as 1936, Camp proposed the use of an ideal settling tank to simulate the entire sedimentation process, which resulted in the classical spoil hopper sedimentation model1. Subsequently, Camp considered the effect of turbulent diffusion on the settling of sand grains2. Yagi presented a model based on the concentration distribution of the open channel flow from the Camp model3. Vlasblom and Miedema had re-estimated overflow losses and deposition efficiency by adding relevant factors that hinder sedimentation, erosion, and reduction in flow depth to the Camp model4,5. In Ooijens’s experiments introduced time effects into the model and obtained the overflow rate and density of sand-water mixtures from experimental measurements of the model with a large scale6,7. The above models are relatively simple models developed for the field of sewage and water treatment. Although the sludge sedimentation process in the secondary clarifier has strong similarities to the sediment in the hopper, the former used idealized or simplified mixture inflow and outflow configurations and defined settling tank velocity distributions.

The one-dimensional probabilistic sedimentation models suggested in the literatures8,9 were based on the advection–diffusion equation for multi-sized mixtures and took into account the effects of the vertical velocity component and the sand particle diameter distribution inside the spoil hopper. The two-dimensional complex sedimentation model proposed later was constructed on the basis of the Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes equation and the k-ε turbulence model10. The sedimentation model included multi-component transport of suspended sediment, simulating in more detail the entire process of sediment deposition within the hopper. Braaksma et al.11 developed three different mathematical models, linear, exponential and water-layer, to predict the overflow density. They demonstrated that the overflow density calculated by the water-layer model was closest to the true values using data from the actual dredger. Overall model of the TSHD loading process was then constructed and eventually integrated into the onboard global Model Prediction Controller (MPC)12,13. In literature14, an abbreviated spoil hopper sedimentation model was derived by discussing the factors that influence the rising rate of the sand bed during sediment deposition. Inspired by Braaksma sedimentation model, Jensen and Saremi considered the effect of sediment particle diameter distribution on the deposition process in the spoil hopper and treated the mixture layer on the sand bed as a single layer instead of two layers as suggested by Braaksma15. Konijn developed a two-dimensional complex sedimentation model for the hopper, but the model showed (almost) no entrainment in the inflow jet and the density flow disappeared quite rapidly in the model during the sedimentation simulation16. Motivated by van Rhee’s two-dimensional model, Sloof constructed a new two-dimensional model for the sedimentation process17. However, due to the complexity of the two-dimensional model, the computational time was too long. Therefore, She developed and validated another simple phenomenological layer model. Su et al.18 established a three-dimensional model using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to simulate the movement of different soil grain diameters in the hopper. It was found that the results obtained from the Braaksma sedimentation model and the developed three-dimensional model were consistent.

Most of the above models are based on one- or two-dimensional partial differential equations. Although they can provide an accurate and elaborate description of the physical sedimentation process in the hopper, these models usually contain many unknown or uncertain parameters regarding the ambient characteristics of dredged soils. It also takes a considerable amount of time to solve the two- or three-dimensional sedimentation models. Therefore, the complexity and uncertainty of these models make them unsuitable for use in online onboard controllers. On the other hand, the model developed by Braaksma utilizes a simplified one-dimensional mathematical model in the vertical direction to describe the entire sedimentation process of the spoil hopper12, which contains only four uncertain soil parameters to be estimated, i.e. the sand bed density \(\rho_{{\text{s}}}\), the undisturbed sedimentation velocity \(v_{{s_{o} }}\), the scour flow coefficient \(k_{e}\) and the hindered sedimentation coefficient \(\beta\). The model has already been successfully applied to the MPC to optimize the loading process of the TSHD19. In particular, when the soil type of the excavation is known to be grained with sand, the original four soil parameters are reduced to one parameter of average soil grain diameter \(d_{m}\). This is because all four uncertain soil parameters in the model can be approximated by different analytical equations with \(d_{m}\) as the independent variable20. In addition, the estimated \(d_{m}\) can be applied to other subsystem models of the TSHD, and by substituting the \(d_{m}\) into the Braaksma spoil hopper sedimentation model, important variables such as sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) can be predicted. For all of the above reasons, the Braaksma model is adapted in this paper to solve the estimation problem associated with hopper sedimentation.

Some scientists had already solved some estimation problems closely related to the hopper sedimentation process of the TSHD based on the Braaksma model. In the literature21, the Bootstrap Particle Filter (BPF)22,23 was used to design centralized observer for simultaneous estimation of overflow rate \(Q_{o}\) and density \(\rho_{o}\), but the results suffered from high variance. Afterwards, the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF)24 and the BPF were combined to construct a cascaded observer and the outputs were compared with the centralized observer for estimating overflow losses25. The experimental results indicated that the optimal combination of cascade observer was to apply UKF or BPF for \(Q_{o}\) and BPF for \(\rho_{o}\). Braaksma et al. applied the BPF and Extended Kalman Filter (EKF)26,27 to estimate the overflow losses and dredging forces, respectively28. The Pattern Search (PS) method, combined with actual dredger loading data, achieved better offline estimation of uncertain soil parameters in the spoil hopper sedimentation model12. Stano et al. attempted to perform the BPF to estimate the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) in both the no-overflow and constant-volume stages29. Although the experimental results were relatively accurate, the BPF adopted the resampling technique to avoid particle degeneracy, which could lead to an increase in the computational burden and the occurrence of sample impoverishment. To solve the above problems, the continuous-time Feedback Particle Filter (FPF)30,31, Reduced-Order Particle Filter (ROPF) and Improved Saturated Particle Filter (ISPF) had been used to estimate the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) and other variables for the three stages of no-overflow, constant-volume and constant-load20,32. Because the FPF requires small sampling intervals (< 0.05 s) to ensure high estimation accuracy, but the sampling intervals of the sensors installed on the dredger range from 1 to 30 s. Consequently, if the FPF is used to solve the estimation problem on the TSHD, the FPF may produce inferior or even scattered estimation results. In contrast, the Continuous-Discrete time Feedback Particle Filter (CD-FPF)33 ensures that the accuracy of the estimation results is not significantly degraded at larger sampling interval times. For this reason, Su et al. applied the CD-FPF to estimate the \(d_{m}\) for both the no-overflow and constant-volume phases34. The method was able to provide a precise and rapid estimation of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) even at lower sampling frequencies compared to the BPF. However, the effectiveness of this method for estimating soil parameters under actual vessel conditions had not been verified. In our previous research, the soil parameters were estimated offline by the Genetic Algorithm (GA), Simulated Annealing and Genetic Algorithm (SAGA), Multiple Population Genetic Algorithm (MPGA) and Simulated Annealing and Multiple Population Genetic Algorithm (SAMPGA)35. Compared to other three methods, the SAMPGA had a faster convergence speed and superior accuracy. The estimated results were highly adaptable to different vessel trips in the same dredging area, but the soil parameters had to be re-estimated under different dredging areas and online estimated to adapt to various soil types.

Based on the above discussion, it is believed that the CD-FPF can obtain posterior samples directly from prior samples through its unique innovative error feedback structure, avoiding the BPF importance density function selection and resampling process36. In particular, the estimation accuracy of this method is still well maintained at lower sampling frequencies. The conceptual framework of the paper is shown in Fig. 1. In this paper, we first construct the state space model and fitness function required for the online and offline estimation problems based on the simplified spoil hopper dynamic sedimentation model. Secondly, two methods, CD-FPF-CG based on the constant feedback gain approximation and CD-FPF-GL based on the feedback gain approximation of the Galerkin method31, in numerical simulations to estimate the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\). They are also compared to the BPF and its two improved methods, the Gaussian Particle Swarm Optimization Particle Filter (GPSO-PF)37 and the Auxiliary Particle Filter (APF)38. The estimation method that performs best in the numerical simulations is finally applied to the estimation of actual vessel state variables. In the computational results of numerical simulation, CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL are better than BPF, GPSO-PF and AP in terms of accuracy and stability of estimation, and the operation steps of CD-FPF-CG are simpler than those of CD-FPF-GL. Therefore, CD-FPF-CG is selected as the online estimation method for actual vessel applications. In the calculation results of the actual vessel application, the CD-FPF-CG is able to accurately derive the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) in the online estimation. In addition, SAMPGA has higher estimation accuracy and faster convergence speed than GA, so the offline estimation result of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) from SAMPGA is used as the initial value for the online estimation of the system state variable as a way to improve the accuracy of the online estimation of the CD-FPF-CG. The experimental results show that the estimation accuracy of CD-FPF-CG is less affected by the process noise standard deviation \(w_{5}\) and the sampling interval time \(T_{s}\). Even at higher sampling interval time \(T_{s} = 30\) s, the algorithm still maintains a high estimation accuracy.

This paper is structured in the following way. First, the spoil hopper sedimentation process and its dynamical model are described in section “Spoil hopper sedimentation process and its dynamical model”. The online and offline estimation problems are presented in section “Overflow density”. Section “Height and mass of the sand bed” introduces the methods for solving estimation problems. Then, in section “Soil parameters related to the soil type”, the estimation results from numerical simulations and actual vessel applications of the sedimentation process are shown and discussed. Finally, section “Conclusions” is a summary of the paper.

Spoil hopper sedimentation process and its dynamical model

This section focuses on the specific sedimentation process in the spoil hopper and model this dynamic process.

Spoil hopper sedimentation process

Figure 2 illustrates the overall structure of a TSHD, which consists mainly of the spoil hopper, overflow weir, drag head, dredge pump, suction pipe, suction pipe hanger, and other dredging equipment. The TSHD is normally equipped with one or two suction pipes to transport excavated sediment from the drag head. After it reaches the designated location, the drag head and suction pipe are first slowly lowered through the suction pipe hanger until the drag head just touches the seabed. The dredger then sails at a set speed, using the drag head to break up the clumped soil and excavate sediment from the seabed. At this point, the mixture of soil and water excavated by the drag head is sucked in by the dredge pump and hydraulically transported through the suction pipe to the spoil hopper for sedimentation, and the lower density mixture above the hopper is discharged through the overflow weir to increase the loading capacity of the spoil hopper. Finally, when the hopper is full, the suction pipe is lifted and the loading operation is complete.

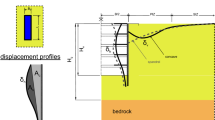

The process of sediment deposition in the spoil hopper is illustrated in Fig. 3. The mixture of soil–water enters the hopper with the flow rate \(Q_{i}\) and density \(\rho_{{\text{i}}}\). The sand grains settle to the bottom of the hopper with the flow rate \(Q_{s}\), gradually forming a sand bed with the height \(h_{s}\) and density \(\rho_{{\text{s}}}\). In the middle of the hopper, unsettled soil–water mixture of the height \((h_{t} - h_{s} - h_{w} )\) and average density \(\rho_{{\text{m}}}\) is generated. As the sediment settles, the water flows in the inverse direction with the flow rate \(Q_{w}\), producing an extremely fine water layer with the height \(h_{w}\) and density \(\rho_{w}\) above the hopper. When the mixture level \(h_{t}\) is higher than the overflow weir height \(h_{o}\), the upper mixture with lower density flows out of the hopper through the overflow weir with the flow rate \(Q_{o}\) and density \(\rho_{{\text{o}}}\), thus causing overflow losses. The mass \(m_{t}\) of sediment loaded into the hopper and the mass \(m_{o}\) of overflow losses depend not only on the soil type, but also on the magnitude of the incoming flow rate \(Q_{i}\) and density \(\rho_{{\text{i}}}\).

The loading process of a TSHD can usually be divided into three distinct stages. A typical spoil hopper loading curve is shown in Fig. 4, which depicts the changes in the total mass \(m_{t}\) of the soil–water mixture in the hopper, the tonnes of dry solids (TDS) and the mass \(m_{o}\) of overflow losses during the loading process. The TDS is the mass of the sediment excluding the water in the pores of the sediment particles39.

Stage 1—No-overflow stage: At this stage, the soil–water mixture level \(h_{t}\) in the spoil hopper does not exceed the overflow weir height \(h_{o}\). All the sediment entering the hopper is stored, and the total mass \(m_{t}\) and the TDS increase rapidly.

Stage 2—Constant-volume stage: As loading process continues, the upper lower density mixture flows out of the overflow weir after the mixture level \(h_{t}\) exceeds the overflow weir height \(h_{o}\). This has the immediate effect of slowing the rate of increase in the total mass \(m_{t}\), but the TDS still continues to increase and at the same time the mass \(m_{o}\) of overflow losses begins to appear. Because the overflow weir height \(h_{o}\) does not change at this stage, the volume of the hopper remains unchanged.

Stage 3—Constant-load stage: When the total mass \(m_{t}\) reaches the maximum draught of the dredger, the overflow weir height \(h_{o}\) is lowered to exclude the lower density soil–water mixture above the hopper, so that the total mass \(m_{t}\) remains unchanged and the sediment loaded in the hopper continues to increase. However, later in this stage, the reduction in the cross-sectional area of the mixture above the sand bed and the increased erosive effect on sand bed resulted in a rapid increase in the mass \(m_{o}\) of overflow losses and a slow increase in the TDS.

In summary, it can be seen that in the TSHD loading process, stage 3 has a lower overflow weir height \(h_{o}\) compared to stages 1 and 2. This results in a more variable flow of the soil–water mixture above the sand bed, giving this stage intricate dynamic characteristics. Therefore, this paper mainly focuses on the investigation and analysis of stages 1 and 2.

Spoil hopper dynamical sedimentation model

The dynamical sedimentation model for the spoil hopper mainly includes hopper volume and mass balance equations, overflow rate and density equations, sand bed height and mass equations and soil parameters equations. In this section, variables are all functions of the time \(t\). The parameter \(t\) is omitted to simplify the symbolic representation, and \(d\) in the equations denotes the differential sign. A complete list of symbolic variables can be found in the Appendix A.

-

1.

Volume and mass balance equations for the spoil hopper

$$dV_{t} = (Q_{i} - Q_{o} )dt$$(1a)$$dm_{t} = (Q_{i} \rho_{i} - Q_{o} \rho_{o} )dt$$(1b)where \(V_{t}\) and \(m_{t}\) are the soil–water mixture volume and mass in the spoil hopper, respectively. \(Q_{i}\) and \(\rho_{i}\) are the mixture flow rate and density entering the hopper, respectively. \(Q_{o}\) and \(\rho_{o}\) are the mixture overflow rate and density, respectively. The above equations reflect the balance between the mixture volume and mass loaded into the hopper in a given period of time.

Assuming that the spoil hopper is a regular rectangular parallel hexahedron with a base area \(A\), the above Eq. (1a) can be transformed into an equation for the mixture level \(h_{t}\):

-

2.

Overflow rate

If the low-density mixture flows through the overflow weir unhindered, the overflow rate \(Q_{o}\) is given by:

When a valve switch is installed in the overflow weir, the overflow rate \(Q_{o}\) is given by:

where \(h_{t}\) and \(h_{o}\) are the mixture level of the hopper and the height of the overflow weir, respectively, and \(k_{{\text{o}}}\) is an uncertain parameter that depends on the geometry and perimeter of the overflow weir.

-

3.

Overflow density

Above the sand bed, the soil–water mixture in the spoil hopper shows a decreasing density with increasing height, so the mixture density distribution in the hopper can be described by a segmented function (water-layer model)11,12.

The mixture average density \(\rho_{m}\) can be given by:

where \(\rho_{{\text{s}}}\) and \(m_{s}\) are the density and mass of the sand bed, respectively, and \(m_{s}\) is derived from the sand bed mass balance Eq. (6).

where \(Q_{s}\) is the sand flow rate and is derived from the following equation:

where \(k_{e}\) is the erosion coefficient, \(v_{{s_{o} }}\) is the undisturbed sedimentation velocity of a single sand grain, \(\beta\) is the hindered settling coefficient, and together with \(\rho_{s}\) in Eq. (5), the four variables mentioned above are closely associated with the soil type and properties. \(\rho_{w}\) is the seawater density (1024 kg/m3), \(\rho_{q}\) is the quartz density (about 2650 kg/m3). \(h_{m}\) is the soil–water mixture height above the sand bed and is given by:

where \(h_{s}\) is the sand bed height.

The overflow rate \(Q_{o}\) consists of the water flow rate \(Q_{w}\) and the mixture flow rate \(Q_{m}\).

The water flow rate \(Q_{w}\) is given by:

Then the overflow density \(\rho_{{\text{o}}}\) obtained after mixing \(Q_{w}\) and \(Q_{m}\) is given by:

The water-layer model for the overflow density \(\rho_{{\text{o}}}\) is given by Eqs. (9)–(11) together.

-

4.

Height and mass of the sand bed

As the TSHD continues to load, the volume \(V_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) of the sand bed formed by the sediment settling in the hopper will gradually increase. The equations for the mass \(m_{s}\) and the volume \(V_{s}\) can be expressed by Eqs. (6) and (12).

Because the hopper is a regular rectangular parallel hexahedron, the Eq. (13) for the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) is obtained by transforming Eq. (12):

-

5.

Soil parameters related to the soil type

When the excavated soil is sand, the four soil parameters \(\rho_{s}\), \(k_{e}\), \(\beta\) and \(v_{{s_{0} }}\) in Eqs. (5) and (7) can be approximated as the analytical form of functions with average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) as the independent variable11,20,40,41.

Estimation problems

This section focuses on the development of the system state equations, the observation equations and the fitness function required for the online and offline estimation problems based on the spoil hopper sedimentation model in the previous section.

Online estimation problem

The stochastic dynamic equations required to estimate the relevant state variables, including the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\), can be derived from the spoil hopper sedimentation model for the no-overflow and overflow stages, respectively. However, the time-varying soil parameter \(d_{m}\) appears to change continuously with the type and nature of the excavated soil, which makes modelling the dynamic changes for the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) extremely difficult. It has been suggested in the literature42 that the process of varying unmodeled uncertain parameters to be estimated can be described by a random walk. Therefore, the following stochastic differential equation is built to describe the dynamics of changing \(d_{m}\).

where \(w_{d}\) is a Wiener process which has a constant standard deviation \(\sigma_{d}\).

Currently, most TSHDs are equipped with various types of sensors that can measure online the total mass \(m_{t}\) and level \(h_{t}\) of the soil–water mixture, as well as the incoming mixture flow rate \(Q_{i}\) and density \(\rho_{i}\). Although real-time measurement devices for the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) have not been successfully developed and applied on a TSHD, it is possible to achieve an accurate online determination of the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) using a conductivity concentration meters under ideal experimental conditions12. This section analyses and discusses the online estimation problem of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) under two different cases, namely the simulated loading operation with a measurable sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and the actual vessel loading operation with an unmeasurable sand bed height \(h_{s}\), in the no-overflow and constant-volume stages, respectively.

-

1.

Case 1—sand bed height can be measured

-

(1)

No-overflow stage.

For the simulated loading situation where the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) can be measured online, based on equilibrium Eqs. (1), (2), (6) and (13) for the mass (\(m_{t}\), \(m_{s}\)) and height (\(h_{t}\), \(h_{s}\)), and the stochastic differential Eq. (15) for the average sand particle diameter \(d_{m}\). The following state vector and input vector can be obtained for the no-overflow stage:

The continuous-time dynamical system model for the no-overflow stage is given by:

where \(w_{t} \,\) is the time-invariant Gaussian process noise with zero mean and \(\sigma_{t}\) standard deviation. \(T_{s} \,\) is the system sampling interval time.

In the case of no-overflow, where the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) is measurable, the system observation vector is given by:

The observation equation is given by:

where \(v_{t} \,\) is the time-invariant Gaussian observation noise with zero mean and \(\varepsilon_{t} \,\) standard deviation, independent of \(w_{t}\).

-

(2)

Constant-volume stage.

The presence of air in the overflow weir prevents accurate and timely measuring of overflow losses. Therefore, it is necessary to explore practical and feasible methods to estimate the overflow rate \(Q_{o}\) and density \(\rho_{{\text{o}}}\) of the soil–water mixture in the overflow weir. Although the spoil hopper sedimentation model includes the models of overflow rate \(Q_{o}\) and density \(\rho_{{\text{o}}}\), there are some uncertain parameters in the models that cause the calculated overflow losses to deviate from the true value. In this paper, a cascade observers are used to achieve decentralized estimation of UKF for \(Q_{o}\) and BPF for \(\rho_{{\text{o}}}\)25, and the above two estimated variables are used as deterministic input variables for the constant-volume stage. The state vector and input vector of the overflow stage are given by:

The continuous-time dynamical system model for the overflow stage is given by :

In case 1, the observation vector and equation for the constant-volume stage are the same as for the no-overflow stage.

-

2.

Case 2—sand bed height cannot be measured

-

(1)

No-overflow stage.

In the case of an actual vessel loading with an unmeasurable online sand bed height \(h_{s}\). The state vector and equation of the continuous-time dynamical system for the no-overflow stage in case 2 are the same as case 1. But the system observation vector is given by:

The observation equation is given by:

-

(2)

Constant-volume stage.

In case 2, the state vector and equation of the continuous-time dynamical system for the constant-volume stage are the same as case 1, and the observation vector and equation of the system are the same as case 2 with no-overflow stage.

In conclusion, the main objective of the online estimation problem for the no-overflow and constant-volume stages is to explore and apply suitable non-linear estimation methods in combination with the simulated and the actual vessel loading data to estimate the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\).

Offline estimation problem

Due to the fact that there is insufficient information about the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) in the actual vessel loading operation. Therefore, it is necessary to combine the spoil hopper sedimentation model and actual vessel loading data, and apply an efficient and appropriate nonlinear intelligent optimization algorithm to estimate the \(d_{m}\), which is used as the initial value for the online estimation of the average sand particle diameter \(d_{m}\) in the actual vessel applications. The fitness function required for the offline estimation problem should be created before estimating the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\). In this paper, the difference between the estimated value of the loaded mass derived from the hopper sedimentation model and the true value obtained from actual measurements is considered to generate the objective function, and the fitness function is an inverted objective function. The objective function is given by the following equation:

where \(\hat{m}_{t} (d_{m} )\) and \(\overline{m}_{t}\) are the model output and measured value of the loading mass at time \(t\), respectively. The smaller the deviation between the two values, the higher the accuracy of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), corresponding to the individual with a higher fitness value in the algorithm. \(H\) is the total number of samples.

Estimation methods

This section introduces several of the non-linear estimation methods used to solve the online and offline estimation problems.

Online estimation methods

The online estimation of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) is a typical non-linear system state estimation problem, so the below five particle filter (PF) algorithms are applied and compared in this paper:

-

1.

BPF: The Bootstrap PF as detailed in Chapter 9 of the book43.

-

2.

GPSO-PF: The Gaussian Particle Swarm Optimized PF as detailed in the literature37.

-

3.

APF: The Auxiliary PF as detailed in the literature38.

-

4.

CD-FPF-CG: The CD-FPF utilises the constant feedback gain approximation as detailed in Chapter 4 of the dissertation33.

-

5.

CD-FPF-GL: The CD-FPF utilises the Galerkin feedback gain approximation as detailed in the literature36. The basis functions of the polynomial are given by \(\left\{ {x_{1} } \right. \, x_{2} \, x_{3} \, x_{4} \, x_{5} \, x_{1}^{{2}} \, x_{2}^{{2}} \, x_{3}^{{2}} \, x_{4}^{{2}} \, x_{5}^{{2}} {\text{\} }}\), where \(x_{i} {\text{ \{ }}i = 1,2,3,4,5\}\) is a component of the state vector in the system state equation.

Among the five PF algorithms mentioned above, BPF, also known as Sampling Importance Resampling (SIR) filtering, generates a set of particle population with initial weights in the state space that correspond to the empirical conditional distribution of the system’s state vector. It then continuously updates the weights and positions of the particles with the latest measurements to ensure that the adapted particle information is close to the posterior distribution of the state vector. The BPF applies a systematic resampling technique44 at each discrete time step to avoid particle degeneracy, using the more easily implemented prior probability density as the importance density function. The other two algorithms, GPSO-PF and APF, are improved BPF algorithms by introducing the intelligent optimization algorithm and improving the resampling technique. For reasons of space, more detailed information on the three algorithms can be found in the relevant literature and are not be repeated here, while the implementations of the two algorithms CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL are described below.

For the continuous-discrete time estimation problem, the system state and observation equations are given by

where \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {x_{t} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{d} } \\ \end{array}\) and \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {u_{t} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{d} } \\ \end{array}\) are the state and input vectors of the system at continuous time \(t\), respectively. \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {z_{k} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{m} } \\ \end{array}\) is the measurement of the system at discrete time \(t_{k}\).\(f( \cdot ) = (f_{1} , \ldots ,f_{d} )\) and \(h( \cdot ) = (h_{1} , \ldots ,h_{m} )\) are the state transfer and observation functions of the system, respectively, and both belong to the \(C^{1}\) function. \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {w_{t} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{d} } \\ \end{array}\) and \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {v_{k} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{m} } \\ \end{array}\) are Gaussian process noise and Gaussian observation noise with mutually independent zero mean and covariance matrices of \(Q\) and \(R\), respectively. The objective of the estimation problem (21) is to derive the posterior distribution \(\pi_{t|t}\) of the system state vector \(x_{t}\) based on the historical observation sequence \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {Z_{t} = \sigma \{ z_{k} :\forall \, k, \, t_{k} \in [0,t]\} } \\ \end{array}\).

CD-FPF is a controlled particle ensemble system based on an innovative error feedback structure that treats each particle as a controllable stochastic system. Each particle under the influence of feedback control can be divided into two steps to realize the evolution by its own state and the empirical distribution characteristics of the particle ensemble, as depicted in Fig. 5 for the schematic diagram of the CD-FPF two-step evolution structure33.

In Step 1, at time \(t \in [t_{k - 1} ,t_{k} )\), the dynamics of the \(i\)-th particle can be expressed as follows:

where \(\{ x_{t}^{i} , \, i = 1, \ldots ,N\}\) is the state of the \(i\)-th particle at time \(t\), and \(N\) is the number of particles. At the start time \(t = 0\), all particles are sampled from the prior distribution \(p*(x,0)\). Assuming that the state \(x_{{t_{k - 1} }}^{i}\) of the \(i\)-th particle at the previous time is known, the right limit of the state \(x_{t}^{i}\) is defined as

In Step 2, when the latest measurement \(z_{k}\) is obtained at a discrete time \(t = t_{k}\), a particle flow \(S_{k}^{i} (\lambda )\) is introduced in the form of differential equations to account for this observation.

where the parameter \(\lambda\) is the pseudo time, which can be conceptualised as the time \(t\) in the continuous time FPF45,46. If the initial state \(S_{k}^{i} (0) = x_{{t_{k}^{ - } }}^{i}\) of the \(i\)-th particle is known, then after iterative computation, the state of the \(i\)-th particle at time \(t = t_{k}\) is \(x_{{t_{k} }}^{i} = S_{k}^{i} (1)\). \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {K_{k}^{i} (S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ),\lambda ) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{d \times m} } \\ \end{array}\) is the feedback gain function, \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {u_{k}^{i} (S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ),\lambda ) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{d} } \\ \end{array}\) is the correction term, and \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {I_{k}^{i} (S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ),\lambda ) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{m} } \\ \end{array}\) is the update term based on the innovation error.

where \(\hat{h} \approx \frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{N} {h(S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ))}\). It can be seen from Eq. (25) that the CD-FPF has a high similarity to the Kalman Filter (KF) in terms of its feedback control structure.

The critical part of the CD-FPF is the derivation of the gain function in Eq. (24). It is common to consider the Kullback–Leibler divergence (KLD) as a measure of the difference between the true posterior probability distribution and the feedback posterior probability distribution. The solution of the feedback gain via the Euler–Lagrange boundary value problem (E-L BVP) is derived by minimising the equivalent of the KLD. For \(j = 1,2, \ldots m\), the function \(\phi = (\phi_{1} , \ldots \phi_{m} )\) is the solution of the following second-order differential equation,

where \(p(S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ),\lambda )\) is the conditional distribution of \(S_{k}^{i} (\lambda )\) for the observation sequence \(Z_{t}\). In these solutions, for \(l = 1,2, \ldots d\), the gain function is:

The CD-FPF solves for the feedback gain \(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {K_{l \, j}^{i} (S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ),\lambda )} \\ \end{array}\) at each discrete time step, and its two approximation algorithms can be divided into the constant feedback gain approximation solution in Algorithm 1 and the Galerkin finite-element method feedback gain approximation solution in Algorithm 231.

The function \(u_{k}^{i} (S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ),\lambda )\) is given by

where \(\Omega = \nabla \phi\) is obtained by solving the following equation:

where \(g = \sum\limits_{j = 1}^{m} {\nabla \phi_{j} } \cdot \nabla h_{j}^{T}\) and \(\hat{g} = \left| {\hat{h}} \right|^{2} - \widehat{{\left| h \right|^{2} }}\), and \(\widehat{{\left| h \right|^{2} }} \approx \frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{N} {h(S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ))^{T} } h(S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ))\).

The solution of the correction term \(u_{k}^{i} (S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ),\lambda )\) in Eq. (24) is similar to that of the feedback gain \(K_{k}^{i} (S_{k}^{i} (\lambda ),\lambda )\), except that \(h\) and \(\hat{h}\) are replaced by \(g\) and \(\hat{g}\) in algorithms 1 and 2 respectively.

To simulate the CD-FPF, the variables \(t\) and \(\lambda\) require Euler-discretization. Then Algorithm 3 is the discretized algorithm33.

Offline estimation methods

The offline estimation of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) is achieved by combining SA (Simulated Annealing, SA)47 with strong local search capability and MPGA (Multiple Population Genetic Algorithm, MPGA)48 with strong global search capability to form the SAMPGA (Simulated Annealing and Multiple Population Genetic Algorithm, SAMPGA). The hybrid algorithm is applied to the spoil hopper sedimentation model for fast and accurate estimation of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\). Since SAMPGA incorporates the “annealing” operation, it can effectively overcome the “premature” phenomenon in the traditional genetic algorithm (GA). Furthermore, the SAMPGA uses multiple populations simultaneously to carry out genetic operations such as selection, crossover, mutation, migration, etc., which enhances the search ability and efficiency of the hybrid algorithm in the solution space. The implementation process of the SAMPGA is depicted in Fig. 6.

The detailed steps of SAMPGA are as follows:

Step 1: Initialization algorithm control parameters: these include the number of populations as \(M_{p}\), the number of individuals in the population as \(NP\), and the number for generations of optimal individuals maintained in the elite population as \(MN\). Generation gap probability \(P_{n} (I)\), crossover probability \(P_{{\text{c}}} (I)\) and variance probability \(P_{{\text{m}}} (I)\) for different populations, where \(I \in [1 M_{p} ]\). Initial annealing temperature \(T_{0}\), temperature cooling factor \(k_{c}\) and final annealing temperature \(T_{end}\).

Step 2: For each population within the boundary region, randomly create \(NP\) individuals as an initial population, and calculate the corresponding individual fitness values for each population.

Step 3: Multiple populations evolve in parallel and set the evolutionary generation count variable \(GEN\) = 0.

Step 4: Multiple populations independently and synchronously perform genetic operations and compare the fitness values of the new and old individuals in each population. If the fitness value of the new individual is greater than the old individual, the new individual replaces the old one. Conversely, either the new or the old individual is selected according to the probability provided by the Metropolis criterion49. After all populations have completed the evolutionary operation, the immigration operator introduces the superior individual produced by one population during the evolutionary process into another population, which in turn serves the purpose of co-evolution of multiple populations.

Step 5: Save the superior individuals (those with the highest fitness values) in the different populations to the elite population. If the number of generations that the superior individuals saved in the elite population remain constant is less than \(MN\), \(gen = gen + 1\), go to step 4; else, go to step 6.

Step 6: When the temperature at time \(i\) is \(T_{i} < T_{end}\), the algorithm is terminated and the global optimal solution is found; conversely, the cooling operation \(T_{i} = kT_{i}\) is performed and return to step 3.

Numerical simulations and actual vessel applications

This section describes and discusses the estimation results obtained from numerical simulations and actual vessel applications of loading operation using the estimation methods presented in the section “Height and mass of the sand bed”. In the two loading situations above, assuming the excavated soil type is known as grained sand, the ranges of average grain diameter \(d_{m}\) for different sand types are given in Table 1.

The normalized mean squaress error (nMSE) and the sample standard deviation (SSD) are used as evaluation indicators to assess the performance of the online estimation methods.

-

1.

The nMSE of the estimate \(\hat{x}\) measures the difference between the estimated value and the actual value in a given time period, which is defined in discrete time:

$$nMSE(\hat{x}) = \frac{1}{M}\sum\limits_{t = 1}^{M} {(\frac{{\hat{x}_{t} - \overline{x}_{t} }}{{\overline{x}_{t} }})^{2} }$$(30)where \(\hat{x}_{t}\) and \(\overline{x}_{t}\) are the estimated and actual values at time \(t\), respectively. \(M\) is the total number of samples.

-

2

The SSD of the estimate \(\hat{x}_{t}\) measures the concentration degree of the \(i\)-th particle \(\hat{x}_{t}^{i}\) near the estimate \(\hat{x}_{t}\) at time \(t\), which is defined as

$$SSD(\hat{x}_{t} ) = \sqrt {\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{N} {(\hat{x}_{t}^{i} - \sum\limits_{j = 1}^{N} {w_{t}^{j} \hat{x}_{t}^{j} )^{2} } } }$$(31)where \(w_{t}^{i}\) is the weight corresponding to the particle \(\hat{x}_{t}^{i}\) at time \(t\). \(N\) is the number of particles.

The algorithmic program used for the results presented in this section was written and implemented on MATLAB version 2019a, running on Windows 10 operating system, Intel core i7 processor with 2.50 GHz and 16 GB of RAM.

Numerical simulations results

In the numerical simulations of loading, the spoil hopper is a regular rectangular parallel hexahedron with base area \(A = 1050\)[m2], and the incoming flow rate \(Q_{i1}\), \(Q_{i2}\) and density \(\rho_{i1}\), \(\rho_{i2}\) of the left and right suction pipe are constant 6 [m3/s] and 1370 [m3/s], respectively. This approximates the basic dimensions of the hopper and the actual incoming flow rate and density of the dredger “Xinhaihu 8” for the actual vessel applications in section “Actual vessel applications results” below.

Five estimation methods, BPF, GPSO-PF, APF, CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL, presented in the previous section, have been used to estimate online the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) for the no-overflow and constant-volume stages. Section “Numerical simulations results” examines the effect of different process noise standard deviations \(w_{5}\) and sampling interval times \(T_{s}\) on the estimated performance of the five algorithms, and the results are obtained from 100 Monte Carlo runs.

BPF and its improved algorithms GPSO-PF and APF resampling methods are both chosen for systematic resampling. The number of particles was set at 1000 for the three algorithms to ensure that the accuracy and precision of their estimates were not affected. Because the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL can rely on their own feedback structure to obtain the posterior samples directly from the prior samples, which requires fewer particles. Therefore, the number of particles for the two algorithms is set to 50. Furthermore, the crucial parameters \(\Delta t\) and \(\Delta \lambda\) are set to 0.05 and 0.01 for both the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL. The smaller the values of the two parameters, the higher the estimation accuracy, but the longer the computation time. The detailed parameters of five algorithms are given in Table 2.

In order to compare and analyse the robustness of the five estimation methods for the initial conditions in the numerical simulations of the no-overflow and constant-volume stages, an initial grained sand offset of + 0.15 has been set on the time-varying soil parameter \(d_{m}\). The initial values of the remaining state variables for the no-overflow and constant-volume stages are given in the corresponding Tables 3 and 4.

-

1.

No-overflow stage.

In the numerical simulation with no-overflow stage, the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) increases continuously and slowly from 0.1 mm fine grained sand at the beginning to 0.3 mm medium grained sand at the end in the first half of the time, and \(d_{m}\) increases stepwise from 0.3 mm medium grained sand at the beginning to 0.6 mm coarse grained sand at the end in the other half of the time. The former simulates the continuous change in dredged soil type when the TSHD is loaded at the same dredge site, while the latter simulates loading at different dredge sites where the difference in dredged soil type is evident. The initial values at the start of the no-overflow stage are shown in Table 3 and the total simulation time is 20 min.

Figures 7, 8 and 9 show the online estimation results of the five algorithms for the no-overflow stage under different sampling interval times \(T_{s}\) and process noise standard deviations \(w_{5}\), respectively. In addition, Figs. 10, 11 and 12 show the corresponding SSDs obtained at different times in the above mentioned instances. Tables 4 and 5 show the obtained nMSEs and average computation times at each time step of the five algorithms for more different process noise standard deviations \(w_{5}\) and sampling interval times \(T_{s}\), respectively.

It can be seen from Figs. 7, 8 and 9 that, except for the sampling interval time \(T_{s}\) = 30 s, the five algorithms estimate the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) very close to the true value. This suggests that all five algorithms can provide accurate estimates of the sand bed height \(h_{s}\). However, for the estimates of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) and the sand bed mass \(m_{s}\), different process noise standard deviations \(w_{5}\) and sampling interval times \(T_{s}\) affect the estimation results of BPF, GPSO-PF and APF, indicating that the three algorithms are more sensitive to the process noise standard deviation \(w_{5}\) and the sampling interval time \(T_{s}\). On the other hand, the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL are more robust to the \(w_{5}\) and \(T_{s}\), which is also reflected in Tables 4 and 5. The average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) and the sand bed mass \(m_{s}\) estimated by both methods consistently show a small deviation from the true values. In addition, the proper adjustment of \(w_{5}\) and \(T_{s}\) can change the convergence speed of CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL, as can be observed in Figs. 7c, 8c and 9c.

When the process noise standard deviation \(w_{5}\) or the sampling interval time \(T_{s}\) is varied, the SSDs obtained from CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL maintain small values and fluctuate with less variation compared to BPF, GPSO-PF and APF (compare Fig. 10 with 11 and Fig. 11 with 12).

As can be seen from the results in Tables 4 and 5, both CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL obtain small values of nMSEs for average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\), indicating that the two algorithms have high estimation accuracy and stability. On the other hand, the other three algorithms gave large values of nMSEs for the above three variables, indicating that their estimation accuracy is not high. In terms of computation time, BPF and APF are fastest, CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL are intermediate and GPSO-PF is slowest (see Tables 4 and 5). The computation time of CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL increases continuously with increasing the sampling interval time \(T_{s}\), while the computation time of BPF, APF and GPSO-PF is not affected by the \(T_{s}\).

-

2.

Constant-volume stage.

In the numerical simulation with constant-volume stage, the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) decreases continuously and slowly from 0.6 mm coarse grained sand at the beginning to 0.3 mm medium grained sand at the end in the first half of the time, and \(d_{m}\) decreases stepwise from 0.3 mm medium grained sand at the beginning to 0.1 mm fine grained sand at the end in the other half of the time. The initial values at the start of the constant-volume stage simulation are shown in Table 6. The overflow weir height is 15.45 m and the total simulation time is 20 min.

Figures 13, 14 and 15 show the online estimation results of the constant-volume stage for the five algorithms under different sampling interval times \(T_{s}\) and process noise standard deviations \(w_{5}\), respectively. Figures 16, 17 and 18 show the corresponding SSDs obtained at different times in the above mentioned instances. Tables 7 and 8 show the nMSEs of the estimates and the average computation time at each time step of the five algorithms for more different process noise standard deviations \(w_{5}\) and sampling interval times \(T_{s}\), respectively.

Similar to the no-overflow stage, except for the sampling interval time \(T_{s}\) = 30 s, the five algorithms for the constant-volume stage all give an accurate estimate of the sand bed height \(h_{s}\). But there is some bias in the BPF, GPSO-PF and APF estimates of the sand bed mass \(m_{s}\), and the GPSO-PF and APF estimates of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) are divergent (see Figs. 13, 14 and 15). On the other hand, the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) derived by the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL are always close to the true values, and both algorithms have smaller nMSEs of the estimates (see Tables 7 and 8). These results illustrate that CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL show strong robustness to variations in \(w_{5}\) and \(T_{s}\).

In the numerical simulations of the constant-volume stage, the SSDs of CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL are kept close to the low values with a small degree of fluctuation. In contrast, the SSDs of the other three estimation methods are more variable at different times. In particular, the SSDs of the BPF, GPSO-PF and APF produce a large degree of fluctuation when \(d_{m}\) undergoes a step change (observe Figs. 16, 17 and 18).

The computation time of the five algorithms in the numerical simulations for the constant-volume stage is similar to that for the no-overflow stage and is not repeated here.

The experimental results of the numerical simulations for the no-overflow and constant-volume stages indicate that the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL have higher estimation accuracy than the BPF, GPSO-PF and APF at different process noise standard deviations \(w_{5}\) and sampling interval times \(T_{s}\). Although the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL show similar estimation performance in the simulations. But the CD-FPF-CG has relatively simple steps, less computation time and can estimate the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) more accurately at larger sampling interval times \(T_{s}\). For these reasons, the CD-FPF-CG is selected as the estimation method for actual vessel applications in the next section.

Actual vessel applications results

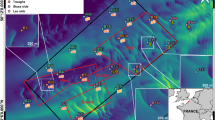

In order to provide an accurate estimate of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) in actual vessel applications. The data from three vessel trips of the TSHD “New Haihu 8” during the normal loading operation at the Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port in China are collected and collated. It is also known that the soil types at the two dredging sites are mainly fine grained sand and medium grained sand, respectively. Each vessel trip consists of multiple sets of data samples with a sampling interval of \(T_{s}\) = 30 s. In turn, each set of data sample contains eight dimensions of data measured by the instruments, including overflow weir height, left and right suction pipe incoming flow rate and density, spoil hopper loading height, capacity and mass. Because the initial average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) is unknown in the actual vessel applications. Therefore, the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) must be estimated off-line using actual data from the entire vessel and a suitable non-linear optimization method.

1. Determination of the initial \(d_{m}\)

The Savitzky-Golay filter50 is applied to remove noise from the data samples before estimating the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\). Then the data of first vessel from Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port are selected and the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) is estimated 100 times using SAMPGA and GA respectively. Figure 19 shows the variation of the objective function values of the algorithms during the evolutionary process, where the number of evolutionary generation is chosen as 20.

The SAMPGA and GA selection operators adopt stochastic universal sampling, and the crossover and mutation modes are linear recombination with mutation characteristics and real-valued mutation, respectively. The crossover probability \(P_{c}\) and the variance probability \(P_{m}\) for the different populations are taken as random numbers within the intervals [0.7 0.9] and [0.001 0.05], respectively. More details on the setting of the control parameters for the two algorithms are given in Table 9.

Compared to the evolutionary process of GA, SAMPGA maintains a lower objective function value from the first generation and can converge to the minimum objective function value rapidly. Therefore, in this paper, SAMPGA is chosen to estimate initial \(d_{m}\) offline.

To verify the accuracy of \(d_{m}\) derived from the SAMPGA offline estimation, the \(d_{m}\) was substituted into the Braaksma hopper sedimentation model to calculate the loading mass and compared with the measured mass as a reference (see Fig. 20). It can be seen from Fig. 20 that there is a deviation between the model output values and the measured results of loading mass for the first vessel trip at the Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port. Especially at the beginning of the overflow stage (15thmin at the Yangtze Estuary and 13thmin at the Xiamen Port), the deviation is more obvious. In addition, the relative error distribution interval between the model outputs and the measured results has a small range, which is consistent with the normal distribution.

The average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) and the optimal objective function value \(J\) for the three vessel trips at the Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port, obtained from the offline estimation using the SAMPGA, are shown in Table 10.

The results in Table 10 show that the optimal objective function values of \(J\) for the three vessel trips in the Yangtze Estuary are all smaller than those in the Xiamen Port, indicating that the accuracy of the offline estimation of the fine sand particle diameter in the Yangtze Estuary is better than that of the medium sand in the Xiamen Port, but the resulting objective function value \(J\) is still on the large side. Therefore, online estimation of the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) is required to minimise the deviation of the estimated value from the actual value, and the offline estimate can be used as the initial \(d_{m}\) for the CD-FPF-CG.

-

2.

No-overflow and constant-volume stages

In the no-overflow stage of the actual vessel applications, the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) derived from the offline estimation and sample data group 1 of each vessel trip are used as the initial values of the CD-FPF-CG. In the constant-volume stage, the final state variables obtained from the estimation of the no-overflow stage are used as the initial values for the CD-FPF-CG. The parameters of the CD-FPF-CG are identical to those in Table 2, except for \(w_{5}\) = 0.001 mm. The significant parameters \(\Delta t\) and \(\Delta \lambda\) are given as 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. The online estimation results for both the no-overflow and constant-volume stages are obtained from 100 Monte Carlo simulations.

Figures 21, 22 and Figs. 23, 24 display the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) derived by the CD-FPF-CG in the no-overflow and constant-volume stages of the first vessel trip in the Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port, respectively.

It can be observed from Figs. 21, 22 and Figs. 23, 24 that the height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) of the sand bed tend to increase linearly as the TSHD loading process progresses during the no-overflow stage. In the constant-volume stage, the increase rate of the sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) slows down due to the presence of overflow losses. Furthermore, the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) obtained from online estimation did not change significantly. This is because the data samples are collected from fixed dredging sites in the Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port, respectively. The average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) of first vessel trip from the Yangtze Estuary increases continuously and slowly in both no-overflow and constant-volume stages. On the other hand, the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) of the first vessel trip from Xiamen Port fluctuates around \(d_{m}\) = 0.27 mm in the no-overflow stage, while the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) increases continuously in the constant-volume stage. The ranges of \(d_{m}\) estimated for the two dredging sites are consistent with the real situations of 0.06–0.20 mm for fine grained sand in the Yangtze Estuary and 0.20–0.60 mm for medium grained sand at the Xiamen Port.

Tables 11 and 12 provide the nMSEs of the loading mass \(m_{t}\) and the height \(h_{t}\) estimates and the average computation time at each time step for the three vessel trips with no-overflow and constant-volume stages at the Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port, respectively.

The results in Tables 11 and 12 display smaller nMSEs for the estimates of loading mass \(m_{t}\) and height \(h_{t}\) in the no-overflow and constant-volume stages. Combined with the lower average computational time taken by the CD-FPF-CG at each time step, it illustrates the accuracy and efficiency of the CD-FPF-CG for online estimation.

Discussion

Numerical simulations results suggest that the BPF, GPSO-PF and APF are more sensitive to the process noise standard deviations \(w_{5}\) and the sampling interval times \(T_{s}\). This means that the estimation performance of the three algorithms can be effectively improved by choosing appropriate \(w_{5}\) and \(T_{s}\). Contrary to this, the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL are robust to variations in \(w_{5}\) and \(T_{s}\), as they always have smaller nMSEs of the estimates (see Tables 4, 5, 7 and 8). Furthermore, the reasonable tuning of the two parameters can improve the convergence speed of the two algorithms (compare Fig. 7c with Fig. 8c and Fig. 13c with Fig. 14c). The CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL provide consistently high estimation accuracy with few particles, even at larger sampling intervals \(T_{s}\) (see Figs. 9, 15 and Tables 5, 8). Whereas the BPF, GPSO-PF and APF suffer from degraded estimation performance with increasing \(T_{s}\).

The SSDs of the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL estimates remain small regardless of the no-overflow and constant-volume stages. This indicates that both algorithms have a larger number of particles concentrated close to the estimates, but the BPF, GPSO-PF and APF have a greater degree of fluctuation in the SSDs at different times.

In terms of computational efficiency, the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL differ in the two critical steps of the importance sampling (involves point-by-point multiplication) and the resampling (involves the entire particle population) for the BPF, GPSO-PF and APF. Based on the innovative error feedback structure, the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL can obtain the posterior samples directly from the prior samples without the need for importance sampling and resampling, which significantly reduces the computational burden. When the \(T_{s}\) is fixed, the GPSO-PF takes the longest time to compute because it incorporates the complex particle swarm intelligence algorithm to make most of the particles move towards the high probability region before the weights are updated. The CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL need to calculate the feedback gain at each time step, which increases the computation time. As the \(T_{s}\) gradually increases, the computation time of CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL increases rapidly due to the fact that the number of consecutive time \(t \in [t_{k - 1} ,t_{k} )\) computation steps increases for both algorithms at each time step, while the computation time of BPF, GPSO-PF and APF does not change significantly.

Considering the similar performance of the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL in numerical simulations and the relatively simple steps to calculate the feedback gain using the CD-FPF-CG. The CD-FPF-CG is therefore applied to estimate soil parameters and related variables in actual vessel applications. Normally, at the beginning of the TSHD loading operation, the density of the mixture of sand and water excavated by the drag head is low. In addition, the “Xinhaihu 8” dredger has a large spoil hopper bottom area of \(A = 1050\) m2. These factors result in no substantial increase in the height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) of the sand bed at the Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port during the initial period (7 min in the Fig. 21a, b and 4 min in the Fig. 23a, b). Furthermore, because the medium grained sand from the Xiamen Port settles more easily in the hopper than the fine grained sand from the Yangtze Estuary. As a result, the height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) of the sand bed in Xiamen Port increases more rapidly than in the Yangtze Estuary (see Figs. 21a, b, 22a, b, 23a, b and 24a, b).

Conclusions

In this paper, based on an abbreviated one-dimensional spoil hopper sedimentation model, the equations of state and observation required for the estimation problems are constructed. Then five non-linear algorithms, BPF, GPSO-PF, APF, CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL, are applied by combining simulated and measured data to estimate online the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) for the numerical simulations and actual vessel applications.

To test and compare the performance of the five estimation methods, continuous and step changes in sand grain diameter are imitated in multiple numerical simulations. The experimental results indicate that the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL outperform the BPF, GPSO-PF and APF in estimation accuracy and precision, regardless of the changes in the process noise standard deviations \(w_{5}\) and the sampling interval times \(T_{s}\). In terms of computational time, the GPSO-PF calculation takes the longest time, the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL have a moderate computational time increasing with \(T_{s}\), and the BPF and APF calculations require the least time.

Although the CD-FPF-CG and CD-FPF-GL show similar performance in numerical simulations, it can be concluded that the CD-FPF-CG exceeds the CD-FPF-GL in both numerical accuracy and efficiency. Therefore, in the actual vessel applications, this paper first applies the SAMPGA to estimate the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\) offline, which is used as the initial value for the CD-FPF-CG online estimation. The CD-FPF-CG is then used to estimate the average sand grain diameter \(d_{m}\), sand bed height \(h_{s}\) and mass \(m_{s}\) online for the first vessel trip at the Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port, respectively. The final estimation results display that the estimates \(d_{m}\) at the two dredging sites are consistent with the actual situation of the sand grain diameter distribution ranges in the Yangtze Estuary and Xiamen Port, and the nMSEs of the loading mass \(m_{t}\) and the height \(h_{t}\) are small.

The final results of the numerical simulations and the actual vessel applications indicate that the CD-FPF-CG can better solve the spoil hopper estimation problem in the no-overflow and constant-volume stages, which is of great importance for optimizing the loading performance of the TSHD and creating an artificial intelligent dredging system.

Future research will select non-linear estimation methods with better performance and attempt to solve the spoil hopper estimation problems for the no-overflow and constant-volume, constant-load overflow stages. While the loading stages considered in this paper only include the no-overflow and constant-volume stages. Besides, the choice of the basis function is related to the accuracy and efficiency of the gain function solution, and the synthesis of the gain function is the core problem of the CD-FPF. Therefore, the determination of the optimal basis function is a problem that needs to be focused on in the following.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to [Because the harrowing suction dredger loading data involves commercial secrets, disclosure may cause security risks, so it is not easy to disclose.] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Camp, T. R. A study of the rational design of settling tanks. Sewage Works J. 8, 742–758 (1936).

Camp, T. R. The effect of turbulence on retarded settling. In Proc. of the 2nd Hydraulics Conference, Iowa City 307–317 (1943).

Yagi, T. Sedimentation effects of soil in hopper. In Proc. of 3rd World Dredging Conference 1–22 (1970).

Vlasblom, W. J. & Miedema, S. A. A theory for determining sedimentation and overflow losses in hoppers. In Proc. of the 14th World Dredging Conference, Amsterdam 183–202 (1995).

Miedema, S. A. & Vlasblom, W. J. Theory for hopper sedimentation. In Proc. of the 29th Annual Texas A&M Dredging Seminar, New Orleans 1–23 (1996).

Ooijens, S. C. Adding dynamics to the camp model for the calculation of overflow losses. Terra Aqua. 76, 12–21 (1999).

Ooijens, S. C., de Gruijter, A., Nieuwenhuijzen, A. & Vandycke, S. Research on hopper settlement using large-scale modeling. In Proc. of the CEDA Dredging Days 1–11 (2001).

van Rhee, C. Numerical simulation of the sedimentation process in a trailing suction hopper dredge. In Proc. of 16th World Dredging Conference, Kuala Lumpur 1–13 (2001).

van Rhee, C. Modelling the sedimentation process in a trailing suction hopper dredger. Terra Aqua. 86, 18–27 (2002).

van Rhee, C. On the sedimentation process in a trailing suction hopper dredger (Ph.D. dissertation). Delft University of Technology (2002).

Braaksma, J., Klaassens, J. B., Babuška, R. & de Keizer, C. A computationally efficient model for predicting overflow mixture density in a hopper dredger. Terra Aqua. 106, 16–25 (2007).

Braaksma, J. Model-based control of hopper dredgers (Ph.D. dissertation). Delft University of Technology (2008).

Braaksma, J., Osnabrugge, J., Babuška, R., de Keizer, C. & Klaassens, J. B. Artificial intelligence on board of dredgers for optimal land reclamation. In Proc. of the CEDA Dredging Days, Rotterdam 1–14 (2007).

Miedema, S. A. The effect of the bed rise velocity on the sedimentation process in hopper dredges. J. Dre. Eng. 10, 10–31 (2009).

Jensen, J. H. & Saremi, S. Overflow concentration and sedimentation in hoppers. J. Waterw. Port Coast. 140, 6 (2014).

Konijn, B. J. Numerical simulation methods for sense-phase dredging flows (Ph.D. dissertation). Universiteit Twente (2016).

Sloof, B. Numerical modelling of sedimentation in trailing suction hopper dredgers (M.S. dissertation). Delft University of Technology (2017).

Su, Z., Zhang, X. Y., Yao, Y., Zhu, D. P. & Fu, J. Q. Mathematic modeling and CFD simulation of the sedimentation process in a TSHD. Mar. Georesour. Geotec. 41, 461–475 (2022).

Braaksma, J., Klaassens, J. B., Babuška, R. & de Keizer, C. Model predictive control for optimizing the overall dredging performance of a trailing suction hopper dredger. In Proc. of the 8th World Dredging Conference 1263–1274 (2007).

Stano, P. M. Nonlinear state and parameter estimation for hopper dredgers (Ph.D. dissertation). Delft University of Technology (2013).

Babuška, R., Lendek, Z. S., Braaksma, J. & de Keizer, C. Particle filtering for on-line estimation of overflow losses in a hopper dredger. In Proc. of the 2006 American Control Conference, Minneapolis 5751–5756 (2006).

Doucet, A., Godsill, S. J. & Andrieu, C. On sequential Monte Carlo sampling methods for Bayesian filtering. Stat. Comput. 10, 197–208 (2000).

Arulampalam, S., Maskell, S., Gordon, N. & Clapp, T. A tutorial on particle filters for online nonlinear/non-gaussian Bayesian tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 50, 174–188 (2002).

Julier, S. J. & Uhlmann, J. K. A new extension of the Kalman filter to nonlinear systems. In Proc. of 11th International Symposium on Aerospace/defense Sensing, Simulation and Controls 182–193 (1997).

Lendek, Z. S., Babuška, R., Braaksma, J. & de Keizer, C. Decentralized estimation of overflow losses in a hopper dredgers. Control Eng. Pract. 16, 392–406 (2008).

Mendel, J. M. Lessons in Estimation Theory For Signal Processing, Communications, And Control, Chapter Iterated Least Squares and Extended Kalman Filtering (Prentice Hall, 1995).

Welch, G. & Bishop, G. An introduction to the Kalman filter (Technical report). University of North Carolina (2002).

Braaksma, J., Osnabrugge, J. & de Keizer, C. Estimating the immeasurable:soil properties. In CEDA Dredging Days (Rotterdam 2009).

Stano, P., Lendek, Z. S., Braaksma, J., Babuška, R. & de Keizer, C. Particle filters for estimating average grain diameter of material excavated by hopper dredger. In Proc. of IEEE Conference on Control Applications, Yokohama 292–297 (2010).

Yang, T., Mehta, P. G. & Meyn, S. P. A mean-field control-oriented approach to particle filtering. In Proc. of American Control Conference, San Francisco 2037–2043 (2011).

Yang, T., Laugesen, R. S., Mehta, P. G. & Meyn, S. P. Multivariable feedback particle filter. Automatica 71, 10–23 (2016).

Stano, P. M., Tilton, A. K. & Babuska, R. Estimation of the soil-dependent time-varying parameters of the hopper sedimentation model: The FPF versus the BPF. Control Eng. Pract. 24, 67–78 (2014).

Yang, T. Feedback particle filter and its applications (Ph.D. dissertation). University of Illinois (2014).

Su, Z., Zhou, Z. X., Yu, M. H., Yuan, W. & Fu, J. Q. Online estimation of soil grain diameter during dredging of hopper dredger using continuous-discrete feedback particle filter. Sensor. Mater. 31, 953–968 (2019).

Zhou, B. L., Yu, M. H. & Guo, J. Hybrid optimization algorithm for estimating soil parameters of spoil hopper deposition model for trailing suction hopper dredgers. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 46, 1813–1831 (2024).

Yang, T., Blom, H. A. P. & Mehta, P. G. The continuous-discrete time feedback particle filter. In Proc. of the 2014 American Control Conference, Portland 648–653 (2014).

Krohling, R. A. Gaussian swarm: a novel particle swarm optimization algorithm. In Proc. of IEEE Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems, Singapore 372–376 (2004).

Pitt, M. K. & Shephard, N. Filtering via simulation: auxiliary particle filters. Econ. Pap. 94, 590–599 (1999).

Miedema, S. A. Dredging processes, the loading process of a trailing suction hopper dredge (Lecture Notes). Delft University of Technology (2012).

Rowe, P. N. A convenient empirical equation for estimation of the Richardson-Zaki exponent. Chem. Eng. Sci. 43, 2795–2796 (1987).

Matousek, V. Flow mechanism of sand-water mixtures in pipelines (Ph.D. dissertation). Delft University of Technology (1997).

Ionides, E. L., Breto, C. & King, A. A. Inference for nonlinear dynamical systems. In Proc. of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 18438–18443 (2006).

Bain, A. & Crisan, D. Fundamentals of Stochastic Filtering (Springer, 2010).

Kitgawa, G. Monte Carlo filter and smoother for non-Gaussian nonlinear state space models. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5, 1–25 (1996).

Yang, T., Mehta, P. G. & Meyn, S. P. Feedback particle filter with mean-field coupling. In Proc. of the 50th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control and European control Conference (2011).

Yang, T., Mehta, P. G. & Meyn, S. P. Feedback particle filter. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 58, 2465–2480 (2013).

Mafarja, M. & Mirjalili, S. Hybrid whale optimization algorithm with simulated annealing for feature selections. Neurocomputing 260, 302–312 (2017).

Shi, X., Long, W., Li, Y. & Deng, D. Multi-population genetic algorithm with ER network for solving flexible job shop scheduling problems. PLOS ONE 15, e0233 (2020).

Corana, A., Marchesi, M., Martini, C. & Ridella, S. Minimizing multimodal functions of continuous variables with the “simulated annealing” algorithm Corrigenda for this article is available here. Acm Trans. Math. Softw. 13, 262–280 (1987).

Schafer, R. W. What is a savitzky-golay filter? [lecture notes]. IEEE Signal Proc. Mag. 28, 111–117 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The quality of this paper is greatly enhanced by the contributions of the editors and reviewers. This work was supported by the China Ministry of Industry and Information Technology High Technology Ship Project [Document No. [2019]360].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B. Z. and M. Y. wrote the main manuscript text. X Z. prepared figures 1-8; Z. Z. prepared figures 9-16. N. L. prepared figures 17-22. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, B., Yu, M., Zhou, X. et al. Realtime estimation of average sand grain diameter and sand bed height and mass for a trailing suction hopper dredger. Sci Rep 14, 28343 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78921-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78921-2