Abstract

Immune system regulation is a key indicator of the gut microbiota (GM) influencing disease development. The causal role of the GM in Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and whether it can be mediated by immune cells is unknown. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics for the GM were obtained from the Dutch Microbiota Project (n = 7,738) and the FINRISK 2002 (FR02) cohort (n = 5,959). Inverse variance weighting method (IVW) were used as the main method to evaluate the causal relationship between GM and GBS. Subsequently, the mediating effects of 731 immune traits were evaluated. Additionally, we also executed the Bayesian Weighting algorithm for verification. Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis determined the protective effect of the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway on GBS (IVW: P = 0.0019, OR = 0.4508). It is worth noting that in the causal effects of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway on GBS, the mediated proportions of herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) ( HVEM on CM CD4 + , HVEM on naive CD4 + , HVEM on CD45RA − CD4 + , HVEM on CM CD8br) in the T cell maturation stage on GBS were -0.0398, -0.0452, -0.0414, -0.0425, accounting for 5.00%, 5.67%, 5.19% and 5.34% of the total effect. 11 types of intestinal bacteria might be involved in the pyrimidine deoxyriboside degradation superpathway, including Staphylococcus A fleurettii, AR31,CAG-274 sp000432155, Photobacterium, Acetobacteraceae, Dysgonomonadaceae, NK4A144,Leptospirae, CAG-81 sp000435795, Leptospirales and CAG-873 sp001701165. This study suggests that there is a causal relationship between pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway and GBS, which may be mediated by HVEM on CD4 + and CD8 + T cells. As a bidirectional molecular switch, HVEM plays an important role in T cell regulation. 11 intestinal flora were found to be involved in pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway, and their changes may be related to the occurrence of GBS. However, extensive research is still warranted before microbiome sequencing can be used for prevention and targeted treatment of GBS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an immune-mediated polyradiculoneuropathy characterized by progressive (ascending) limb weakness with diminished or absent reflexes that reaches maximum severity within 4 weeks. The global incidence of GBS is estimated to be 0.81 to 1.89 per 100,000 person-years, with more common in males than females. GBS frequently emerges as a post-infectious disorder. Approximately two-thirds of patients recount symptoms of respiratory or gastrointestinal infection before the onset of GBS1. In recent years, "microbiota-gut-brain axis" has received increasing attention. Differences in the composition and distribution of the gut microbiota (GM) , as well as dysbiome, contribute to the development of several diseases, including GBS2. We now know that the most common pathogen causing pre-infection is Campylobacter jejuni, which is associated with the AMAN subtype of GBS3,4.Humoral and cell-mediated autoimmune responses to recent infections are thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of GBS5. Activated T cells, macrophages, and cytokines participate in the inflammatory process of GBS3. Proinflammatory macrophages (M1) and anti-inflammatory macrophages (M2) play a decisive role in the initiation and development of GBS6. An imbalance between Th1 and Th2 responses in T cell subtypes leads to the development of GBS7. Therefore, we focused on analyzing the GM and the immune cells to investigate their potential association with GBS development.

Although studies have associated GM with GBS, the causal connection between GM and GBS has not been fully determined due to the potential influence of residual confounding and reverse causality. Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis is a statistical method designed to infer potential causal relationships from observations, utilizing instrumental variables (IV) to study genetic causal relationships between exposures and outcomes8. Based on aggregated data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS), this study explored the potential causal relationship between GM and GBS by mediated MR method, and whether it can be mediated by immune cells. The purpose of this study is to provide a theoretical basis and new ideas for the prevention and treatment of GBS.

Materials and methods

Study design

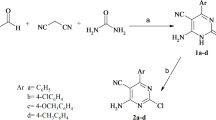

The data used in our study is publicly available and the content covered in the study has been approved by the appropriate institutional review board. In this study, we explored the intercausal relationship between the microbiota and GBS through two-sample two-way Mendelian randomization, and whether immune cell signatures can mediate this association. We defined GM and immune cell-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables (IV). Figure 1 shows a schematic summary of the analysis.

Diagrams illustrating associations examined in this study. (A) The total effect between superpathway of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation and Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). c is the total effect using genetically predicted superpathway of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation as exposure and GBS as outcome, d is the total effect using genetically predicted GBS as exposure and superpathway of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation as outcome. (B) The total effect was decomposed into: (i) indirect effect using a two-step approach (where a is the total effect of superpathway of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation on HVEM on CM CD4 + , HVEM on naive CD4 + , HVEM on CD45RA-CD4 + , HVEM on CM CD8br in the maturation stages of T cell, and b is the effect of HVEM on CM CD4 + , HVEM on naive CD4 + , HVEM on CD45RA-CD4 + , HVEM on CM CD8br in the maturation stages of T cell on GBS) and the product method (a x b) and (ii) direct effect (c’ – c – a x b). Proportion mediated was the indirect effect divided by the total effect. e is a causal relationship analysis process that uses 11 gut microbiota as exposure and superpathway of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation as the result.

Data source

GBS data were obtained from the FinnGen (R10) database (https://www.finngen.fi/en/ access_results). We used two GM data sets, one of which came from 207 taxons (5 phyla, 10 classes, 13 orders, 26 families, 48 genera, 105 species) and 205 pathways representing microbial composition and function from the Dutch Microbiome Project (DMP)9. (Supplementary Table 1). The DMP dataset was obtained by sequencing the feces of 7,738 individuals of European ancestry using shotgun metagenomes.The other set of data contained 473 GM from FINRISK 2002 (FR02) cohort study of 5,959 genotypic individuals with matching GM metagenomic,and dietary and health records10. The FR02 cohort study population was males and females aged 25 to 74 years from six geographical regions of Finland. The overall participation rate was 65.5% (n = 8,798). The blood and stool samples they take are sent to the Finland Institute of Health and Welfare and then shipped to the University of California, San Diego (United States) for processing and sequencing. All GM data can be downloaded from the NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog. Aggregate statistics for 731 immune signatures are publicly available from the GWAS catalogue (accession numbers from GCST0001391 to GCST0002121) (Supplementary Table 2). These features mainly include absolute cell (AC) count (n = 118), median fluorescence intensity (MFI) reflecting surface antigen levels (n = 389), morphological parameters (MP) (n = 32), and relative cell (RC) count (n = 192)11. Among them, the AC, MFI, and RC features contain B cells, CDCs, T cell maturation stages, monocytes, myeloid cells, TBNK (T cells, B cells, natural killer cells), and Treg panels, while the MP features contain CDC and TBNK panels. Raw GWAS data for immune traits were obtained from 3757 Europeans . All GWAS data are sourced from different consortia and organizations, guaranteeing that there is no overlap in the samples.

Filter tool variables

An effective IV needs to meet three basic assumptions : (1) It is closely related to exposure factors. (2) There can be no confounding factors. (3) It only affects the outcome through exposure factors, i.e., there is no pleiotropy12. In order to avoid weak instrumental bias and ensure the independence of the IVs, we set a genome-wide significance level (P < 1.0 × 10–5), a linkage disequilibrium threshold (kb = 10,000, r2 < 0.001), and an F-statistic > 10.The F-statistic can be used to assess weak instrumental variable effects, F = [(N–K–1)/K] / [R2/(1–R2)], where R2 is the variance score explained by genetic variation in the exposure, N is the sample size, and K is the number of SNPs13.

Mendelian randomization analysis

Two-sample MR analysis was performed primarily using the inverse variance-weighted method (IVW) to assess the potential causal relationship between the microbiota and GBS. We also used MR-Egger regression, weighted median method (WME), simple mode (SM), and weighted mode (WM) as supplements to IVW. P < 0.05 was considered to be a significant association between exposure and outcome. Based on the premise that all SNPs are valid instrumental variables, IVW can provide accurate estimates14. When there is pleiotropy in IVs, MR-Egger regression can be used to estimate them. The weighted median has the advantage of maintaining higher accuracy (smaller standard deviation) than MR-Egger regression, providing a consistent estimate even if 50% of the genetic variation is invalid IV15. The simple mode method and the weighted mode method aim to obtain a single estimate of IV causal effects from multiple IVs, and both methods have the advantages of smaller bias and lower probability of class I error. This study was further validated by a Bayesian weighting method to reduce measurement errors and horizontal pleiotropy16. Bayesian weighted mendelian randomization (BWMR) is a new method based on aggregated statistics from GWAS for causal inference. It has been previously reported that a BWMR model is proposed that solves the pleiotropy problem by Bayesian weighting and takes into account the uncertainty of weak effects due to polygenicity. In order to make the BWMR calculation efficient and stable, the variational expectation maximization algorithm (VEM) was also developed to infer the posterior mean of causal effects. Importantly, they further derived an exact closed-ended formula to correct for the posterior covariance. Finally, the application of BWMR to real-world data analysis further demonstrates the statistical properties of BWMR and reveals a new causal relationship between exposure and outcome characteristics17. In addition, we performed reverse-mendelian randomization (r-MR) analyses to assess any potential reverse causality. r-MR analysis is an intuitive way to assess potential reverse causality. In this analysis, the original exposure factor was used as the outcome and the outcome factor was used as the new exposure, and the MR analysis was re-performed. The r-MR analysis procedure is the same as that used for MR analysis18.

Mediation analysis

We used a ‘coefficient product’ approach to assess the indirect effect of the GM on GBS risk through potential mediators. The standard error of indirect effects was determined using the delta method. We calculated the percentage of mediating effect mediated by dividing the indirect effect by the total effect14. Total effect: The causal role of exposure on ending. Direct effect A: The causal role of exposure on intermediary. Direct effect B: The causal role of intermediary on ending. β (indirect effect) = β (Direct effect A) * β (Direct effect B). The mediated proportion = β (indirect effect) / β (total effect).Confidence interval = β (indirect effect) ± 1.96 * SE, β is estimated. SE is a standard error. 1.96 represents the Z-score with a 95% confidence interval (for a normal distribution).

Sensitivity analysis

In order to eliminate confounding instrumental variables and increase the reliability of the study results, Cochran’s Q, MR-Egger, and Leave-One-out methods were used to test the heterogeneity, gene pleiotropy, and sensitivity of IV, respectively16. The statistics and funnel plots of Cochran’s Q test were used to assess heterogeneity between SNPs. When P > 0.05, it was indicated that the effect size of the selected IV was not affected by random fluctuations15. MR-Egger regression analysis was used to detect horizontal pleiotropy. When P > 0.05, it is considered that the possibility of gene pleiotropy in causal analysis is weak and its impact can be ignored, thus enhancing the credibility of estimating causality. Finally, the Leave-One-out method was used to verify the influence of each SNP on the overall causal estimation19. Moreover, we used an online power calculation tool for MR (https://sb452.shinyapps.io/power) to calculate the statistical power of causal effect estimates. A power threshold of 0.8 was considered appropriate, enabling the rejection of 4/5 false null hypotheses20.

Results

GM and GBS

Our study found 20 GM that directly affect GBS (Table 1) . Subsequently, we further validated it by Bayesian weighting, and found that the results of the two methods were highly consistent (Table 2). Among them, pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway and GBS were the most significant, which could reduce the risk of GBS (IVW: P = 0.0019, OR = 0.4508), and the effect power was 87.1%. By r-MR analysis, no significant results were found (P = 0.4044, OR = 0.9754), which could be further mediated analysis (Fig. 2). Importantly, none of our results were heterogeneous or pleiotropic (P > 0.05) (Tables 3, 4), and specific SNPs did not drive causal estimation (Fig. 3).

The MR analysis showed PWY0.1298..superpathway.of.pyrimidine. deoxyribonucleosides.degradation was highly associated with Guillain–barre syndrome. The r-MR analysis showed Guillain–barre syndrome was not associated with PWY0.1298..superpathway.of. pyrimidine.deoxyribonucleosides.degradation. CI: Confidence Interval; MR: Mendelian randomization; r-MR: reverse mendelian randomization: OR: odds ratio; snp: single nucleotide polymorphism.

Immune cell traits and GBS

We investigated the causal effects of the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway on 731 immune cell traits. MR analysis showed that 52 immune cell characteristics were associated with this metabolic pathway (Fig. 4). Among them, 6 immune cell traits were detected by IVW and correlated with GBS (Fig. 6). After further analysis, we found that only CD25hi % CD4 + (IVW: P = 0.0019, OR = 0.7790) had a protective effect on GBS. Additionally, 5 immune cell traits, namely HVEM on CM CD4 + (IVW: P = 0.0088, OR = 1.1067), HVEM on naïve CD4 + (IVW: P = 0.0196, OR = 1.1128), HVEM on CD45RA − CD4 + (IVW: P = 0.0201, OR = 1.1206), HVEM on CM CD8br (IVW: P = 0.0047, OR = 1.1272) and HVEM on EM CD4 + (IVW: P = 0.0253, OR = 1.1269), enhanced the risk of GBS. The statistical p-value of Cochran’s Q test (P > 0.05) indicating that no significant heterogeneity was found (Tables 5, 6) . The MR-Egger intercept test showed no statistical significance (P > 0.05), indicating no horizontal pleiotropy (Table 7, Table 8). The Leave-One-out method showed that removal of specific SNPs did not alter causal estimates (Fig. 5, 7). Bayesian weighting further validates our findings and presents largely consistent trends such as CD25hi % CD4 + (IVW: P = 0.0057, OR = 0.7557), HVEM on CM CD4 + (IVW: P = 0.0126, OR = 1.1145), HVEM on naïve CD4 + (IVW: P = 0.0213, OR = 1.1325), HVEM on CD45RA − CD4 + (IVW: P = 0.0149, OR = 1.1347) and HVEM on CM CD8br (IVW: P = 0.0121, OR = 1.1478). However, the effect of HVEM on EM CD4 + was different (P = 0.0679) (Fig. 8).

MR analysis showed 3 immune cell traits had promoting effect on PWY0.1298..superpathway.of.pyrimidine.deoxyribonucleosides.degradation and 49 immune cell traits had inhibiting effect on PWY0.1298. superpathway.of.pyrimidine deoxyribonucleosides.degradation. CI: Confidence Interval; MR: Mendelian randomization; OR: odds ratio; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism.

Leave-one-out analysis visualizing the Mendelian randomization (MR) estimates of the exposure (PWY0.1298..superpathway.of.pyrimidine.deoxyribonucleosides.degradation) with the different outcomes (A: CD25hi%CD4 + ; B: HVEM on CM CD4 + ; C: HVEM on naive CD4 + ; D: HVEM on EM CD4 + ; E: HVEM on CD45RA-CD4 + ; F: HVEM on CM CD8br).

Mediation analysis

We analyzed the causal relationship between the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway and HVEM in T cell maturation stage ,as well as HVEM in T cell maturation stages and GBS. We also performed separate mediation analyses to characterize the mediating role of HVEM during the maturation phase of T cells in the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway in patients with GBS. The pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway reduced the GBS risk pathway by inhibiting the expression of HVEM (HVEM on CM CD4 + , HVEM on naïve CD4 + , HVEM on CD45RA − CD4 + , HVEM on CM CD8br) at the T cell maturation stage, respectively, by -0.0398, -0.0452, -0.0414, -0.0425, accounting for 5.00%, 5.67%, 5.19% and 5.34% of the total effect (Table 9).

GM (FR02) and pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway

We identified 13 GM that are causally related to the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway. Three GM were protective against GBS, AR31 abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0024, OR = 0.3164), Leptospirae abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0285, OR = 0.4935) and Leptospirales abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0455, OR = 0.5471). In addition, 10 GM raised the risk of GBS, Staphylococcus A fleurettii abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0017,OR = 1.2744), CAG − 274 sp000432155 abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0082,OR = 1.1322), Photobacterium abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0135,OR = 2.4471), Acetobacteraceae abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0200,OR = 2.5260), Dysgonomonadaceae abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0236,OR = 1.7159), NK4A144 abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0273,OR = 1.8098), UBA7748 sp900314535 abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0326,OR = 1.5320), CAG − 81 sp000435795 abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0360, OR = 1.2029), Fimbriimonadia abundance in stool (IVW: P = 0.0489,OR = 1.6649) and CAG − 873 sp001701165 abundance in stool(IVW: P = 0.0494,OR = 1.1062) (Fig. 9). None of our results were heterogeneous or pleiotropic (P > 0.05) (Tables 10,11), and specific SNPs did not drive causal estimation (Fig. 10). Bayesian weights further confirmed the significance of the 11 GM and showed a consistent trend, although the results were different for Fimbriimonadia abundance in stool (P = 0.07450) and UBA7748 sp900314535 abundance in stool (P = 0.5174) (Fig. 11).

Leave-one-out analysis visulizing the Mendelian randomization (MR) estimates of the different exposures (A Staphylococcus A fleuretti abundance in stool; B AR31 abundance in stool; C CAG-274 sp000432155 abundance in stool; D Photobacterium abundance in stool; E Acetobacteraceae abundance in stool; F Dysgonomonadaceae abundance in stool; G NK4A144 abundance in stool; H Leptospirae abundance in stool; I CAG-81 sp000435795 abundance in stool; J Leptospirales abundance in stool; K: CAG-873 sp001701165 abundance in stool) with the outcome (Guillain–barre syndrome).

Discussion

In recent years, the research field of the interaction between the GM and neuroimmune diseases has rapidly become a hot topic. GM regulate many of their functions through multiple mechanisms, including neuromodulatory pathways, endocrine regulatory pathways (via the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis), and immunomodulatory pathways (via lymphocytes, cytokines, chemokines, and metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids)21,22,23. In order to better investigate the causal relationship between GM and GBS, we performed a two-sample MR analysis. In this study, we found that the causal relationship between the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway and GBS was most significant in the GM, and could be used as a protective factor against GBS. The pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway involves the catabolism of pyrimidine nucleotides, including deoxycytosine nucleotides, deoxyuracil nucleotides and deoxythymine nucleotides. In the cell, pyrimidine deoxyribonucleosides can be degraded through different enzymatic reactions to produce important metabolic intermediates that can be further involved in the cell’s energy metabolism and biosynthesis pathways. For example, in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease, oral uridine, omega-3 fatty acids, and choline were found to increase the number of synaptic membranes produced by surviving striatal neurons24. Cytidine and uridine are used in the brain’s phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthetic pathways through the Kennedy cycle and are essential for the maintenance and function of nerve cells. Uridine can be converted to cytosine triphosphate to stimulate the synthesis of cephalin, which may prevent the destruction of myelin25. Hence, the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway, functioning as a protective factor for GBS, might exert a role in the maintenance of nerve cells.

Two-step MR analysis was performed to explore the influence of immune cells as intermediaries between GBS and GM.Our analysis showed that HVEM on CM CD4 + , HVEM on naive CD4 + , HVEM on CD45RA − CD4 + , and HVEM on CM CD8br as key mediators of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway and GBS pathogenesis pathway. The characteristics of these four immune cells all belong to different subgroups of mature T cells and are all associated with herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM). HVEM belongs to the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily, which has been recognized as a new immune target in recent years. HVEM is widely expressed on a variety of immune cells, including dendritic cells, primary T and B cells, NK cells, monocytes, and neutrophils26,27. Ligands that bind to HVEM include BTLA (B- and T- lymphocyte attenuator), CD160, LIGHT (lymphotoxin-like inducible protein that competes with glycoprotein D for herpes virus entry on T cells), lymphotoxin-A, and herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D. As a bidirectional molecular switch, HVEM plays an important role in the regulation of T cells. By binding with BTLA or LIGHT, it transmits pro-inflammatory and survival signals, stimulates the proliferation and activation of lymphocytes, and also inhibits the activation and proliferation of T cells and B cells28. The binding of HVEM to LIGHT or lymphotoxin-A results in a positive stimulatory effect e.g., proliferation and activation of lymphocytes, thus providing a second signal necessary to activate T cells29,30. Furthermore, the HVEM-LIGHT signaling plays a vital role in regulating naïveT cell activation, expansion, and production of cytokines, including pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ31. In view of the influence of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway on T cells, we need to pay attention to the dynamic balance of pyrimidine pool. Activation of T lymphocytes is associated with increased pyrimidine pools32. Pyrimidine pool is the sum of all pyrimidine nucleotides in the cell, and the weakening of pyrimidine nucleotide degradation affects the activation of T cells. Activated T cells are involved in the occurrence and development of GBS. This study found that both HVEM and pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway may affect the occurrence and development of GBS by affecting the activation state of T cells. Therefore, the in-depth study of HVEM signaling pathway and pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway and the development of HVEM or its ligands become a new way to treat GBS.

The GM, also referred to as the intestinal microbiome, is a complex ecosystem consisting of trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protists. The composition of different colonies in the GM may affect the hyperpathway of pyrimidine deoxynucleotide degradation. We utilized additional microbiome project data to explore the gut flora that is causally associated with the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway. We discovered that 11 intestinal flora are involved in the pyrimidine deoxynucleotide degradation superpathway, and changes in the composition of these 11 flora might affect GBS. Among them, Staphylococcus A fleurettii, NK4A144, Photobacterium, Acetobacteraceae, Dysgonomonadaceae, CAG-274 sp000432155, CAG-81 sp000435795 and CAG-873 sp001701165 are beneficial bacteria in intestinal tract, which can promote pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway. Leptospirae, Leptospirales and AR31, as pathogenic bacteria, inhibit pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway. Several articles have reported that GBS can be complicated in the course of Leptospirae and Leptospirales infection33,34,35.

This study provides a new idea for the treatment of GBS, but there are some limitations. First, the study relied solely on data from European populations, which may limit the generality of the conclusions. For a wider range of applications, larger GWAS datasets are needed for future validation. Second, our study used pooled data, rather than individual-level data, which limits our ability to explore subgroup causation, such as gender differences. Meanwhile, it is impossible to avoid the influence of residual confounding factors (gene-environment interactions, lifestyle, etc.) on the disease. Third, the GBS sample size we obtained from the FinnGen database is relatively small, which may lead to some bias in the results. Fourth, our research shows that the maturation stages of T cells mediated by HVEM (HVEM on CM CD4 + , HVEM on naive CD4 + , HVEM on CD45RA − CD4 + , HVEM on CM CD8br) were 5.00%, 5.67%, 5.19%, 5.34%, respectively, which were relatively low. Other intermediaries may also exist and require further attention.

Data availability

The GWAS summary data for Guillain–barre syndrome are available in FinnGen, at https://www.finngen.fi/en/access_results.731 immune cell traits: Ebi-a-GCST0001391 to Ebi-a-GCST0002121, at https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/.

References

Liu, S., Dong, C. & Ubogu, E. E. Immunotherapy of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 14(11), 2568–2579 (2018).

Lee, A. et al. Korean J Gastroenterol. 81(4), 145–153 (2023).

Shahrizaila, N., Lehmann, H. C. & Kuwabara, S. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 397(10280), 1214–1228 (2021).

van den Berg, B. et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 10(8), 469–482 (2014).

Wakerley, B. R. & Yuki, N. Infectious and noninfectious triggers in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 9(7), 627–639 (2013).

Yao, J., Zhou, R., Liu, Y. & Lu, Z. Progress in Guillain-Barré syndrome immunotherapy-A narrative review of new strategies in recent years. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 19(2), 2215153 (2023).

Nyati, K. K., Prasad, K. N., Rizwan, A., Verma, A. & Paliwal, V. K. TH1 and TH2 response to Campylobacter jejuni antigen in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Arch Neurol. 68(4), 445–452 (2011).

Gupta, V., Walia, G. K. & Sachdeva, M. P. “Mendelian randomization”: an approach for exploring causal relations in epidemiology. Public Health. 145, 113–119 (2017).

Lopera-Maya EA, Kurilshikov A, van der Graaf A, et al. Effect of host genetics on the gut microbiome in 7,738 participants of the Dutch Microbiome Project [published correction appears in Nat Genet. 2022 Sep;54(9):1448.

Qin Y, Havulinna AS, Liu Y, et al. Combined effects of host genetics and diet on human gut microbiota and incident disease in a single population cohort [published correction appears in Nat Genet. 2024 Mar;56(3):554.

Wang, C. et al. Causal role of immune cells in schizophrenia: Mendelian randomization (MR) study. BMC Psychiatry. 23(1), 590 (2023).

Sekula, P., Del Greco, M. F., Pattaro, C. & Köttgen, A. Mendelian Randomization as an Approach to Assess Causality Using Observational Data. J Am Soc Nephrol. 27(11), 3253–3265 (2016).

Grover, S., Del Greco, M. F., Stein, C. M. & Ziegler, A. Mendelian Randomization. Methods Mol Biol. 1666, 581–628 (2017).

Chen, J., Yu, X., Wu, X., Chai, K. & Wang, S. Causal relationships between gut microbiota, immune cell, and Non-small cell lung cancer: a two-step, two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J Cancer. 15(7), 1890–1897 (2024).

Yuan J, Xiong X, Zhang B, et al. Genetically predicted C-reactive protein mediates the association between rheumatoid arthritis and atlantoaxial subluxation [published correction appears in Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Feb 23;14:1154170.

Wang, Z. et al. The role of HLA-DR on plasmacytoid dendritic cells in mediating the effects of Butyrivibrio gut microbiota on Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci. 45(8), 3809–3815 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Bayesian weighted Mendelian randomization for causal inference based on summary statistics. Bioinformatics. 36(5), 1501–1508 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Effect of the gut microbiome, plasma metabolome, peripheral cells, and inflammatory cytokines on obesity: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study and mediation analysis. Front Immunol. 15, 1348347 (2024).

Liu, B. et al. Assessing the relationship between gut microbiota and irritable bowel syndrome: a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 23(1), 150 (2023).

Luo, M. et al. Causal effects of gut microbiota on the risk of chronic kidney disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 13, 1142140 (2023).

Doroszkiewicz, J., Groblewska, M. & Mroczko, B. The Role of Gut Microbiota and Gut-Brain Interplay in Selected Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Int J Mol Sci. 22(18), 10028 (2021).

Vuotto, C., Battistini, L., Caltagirone, C. & Borsellino, G. Gut Microbiota and Disorders of the Central Nervous System. Neuroscientist. 26(5–6), 487–502 (2020).

Cao, F., Zhang, H., Xu, B. & Li, C. Genetic association between gut microbiota and the risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Affect Disord. 357, 171–178 (2024).

Vincenzetti, S., Polzonetti, V., Micozzi, D. & Pucciarelli, S. Enzymology of Pyrimidine Metabolism and Neurodegeneration. Curr Med Chem. 23(14), 1408–1431 (2016).

Mironova, G. D. et al. The Protective Effect of Uridine in a Rotenone-Induced Model of Parkinson’s Disease: The Role of the Mitochondrial ATP-Dependent Potassium Channel. Int J Mol Sci. 25(13), 7441 (2024).

Cai, G. & Freeman, G. J. The CD160, BTLA, LIGHT/HVEM pathway: a bidirectional switch regulating T-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 229(1), 244–258 (2009).

Bourque, J. & Hawiger, D. The BTLA-HVEM-CD5 Immunoregulatory Axis-An Instructive Mechanism Governing pTreg Cell Differentiation. Front Immunol. 10, 1163 (2019).

Rodriguez-Barbosa, J. I. et al. HVEM, a cosignaling molecular switch, and its interactions with BTLA, CD160 and LIGHT. Cell Mol Immunol. 16(7), 679–682 (2019).

Sedy, J. R. et al. B and T lymphocyte attenuator regulates T cell activation through interaction with herpesvirus entry mediator. Nat Immunol. 6(1), 90–98 (2005).

del Rio, M. L., Lucas, C. L., Buhler, L., Rayat, G. & Rodriguez-Barbosa, J. I. HVEM/LIGHT/BTLA/CD160 cosignaling pathways as targets for immune regulation. J Leukoc Biol. 87(2), 223–235 (2010).

Wojciechowicz, K., Spodzieja, M., Lisowska, K. A. & Wardowska, A. The role of the BTLA-HVEM complex in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 376, 104532 (2022).

Quéméneur, L. et al. Differential control of cell cycle, proliferation, and survival of primary T lymphocytes by purine and pyrimidine nucleotides. J Immunol. 170(10), 4986–4995 (2003).

Kobawaka Gamage, K. K. & Fernando, H. Leptospirosis complicated with Guillain Barre syndrome, papillitis and thrombotic thrombocytopenic Purpura; a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 18(1), 691 (2018).

Akdoğan, Ö. et al. A Rare Presentation of Leptospirosis: Dysarthria and Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Infect Dis Clin Microbiol. 4(4), 285–288 (2022).

Dev, N., Kumar, R. & Kumar, D. Guillain-Barre syndrome: a rare complication of leptospirosis and scrub typhus co-infection. Trop Doct. 49(3), 248–249 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the participants and investigators of the FinnGen study. We thank all the participants and investigators who provided valuable genetic summary statistics for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. and X.L. conceptualised and designed the study. X.L. and L.L. wrote the frst draf of the manuscript. J.Z. critically revised the draf. All authors contributed to data interpretation, critical revisions, and fnal approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Liu, L. & Zhang, J. Causal role of the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside degradation superpathway mediation in Guillain-Barré Syndrome via the HVEM on CD4 + and CD8 + T cells. Sci Rep 14, 27418 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78996-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78996-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Noninvasive markers for warning premature ovarian insufficiency: a Mendelian randomisation study

Journal of Ovarian Research (2025)

-

The causal effect of gut microbiome on pulmonary artery hypertension based on a two-sample Mendelian randomization study

Nutrition & Metabolism (2025)