Abstract

Cognitive load (CL) is one of the leading factors moderating states and performance among drivers. Heavily increased CL may contribute to the development of mental stress. Averaged heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) indices are shown to reflect CL levels in different tasks. The aim of this large-scale study was to explore how accurately HR and HRV metrics can differentiate between varying CL conditions during driving. Participants (N = 892, 44% female, from 18 to 79 years old) performed simulated driving in highway and urban scenarios. The n-back task was used as a mental distraction to further increase CL. The results have shown that increased CL was accompanied by higher HR, lower HRV, as measured by RMSSD, and higher HR complexity, as measured by permutation entropy. HR displayed the highest accuracy in discriminating between short windows (30 s) of different CL conditions, particularly highway versus urban driving and mental distraction during highway driving. We found gender and age effects on discriminative accuracy of HR and HRV metrics which were related to subjective ratings of CL. These results illustrate that HR and HRV indices provide a valid source for applications in the field of CL monitoring and mental stress detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cognitive load (CL) is a well-known factor contributing to human physiological states, behavior, and task performance, which is particularly relevant to driving1. CL can be defined as the attention effort required for attempting a task, which is limited by the working memory capacity and the cost of switching between tasks2. The road environment (e.g., urban or highway), traffic conditions, navigation demands, potential distractions, and other factors affect how drivers distribute their attention and manage cognitive resources.

Exceedingly high CL is often viewed in relation to stress, and tasks generating high CL are sometimes used for creating conditions for so-called “mental stress”3,4, when an individual is required to mobilize a significant amount of mental resources in order to continue meeting task demands. Causse et al.5 note that, although mental workload and stress should be considered as distinct phenomena, their causes and effects can be very similar. In their study, high workload and auditory threat stressors during solving a task were accompanied by a similar pattern of changes in autonomic and brain activity. Tasks eliciting high CL can also trigger episodes of acute stress. Thus, conclusions from CL studies to an extent can be useful for understanding some of the processes contributing to the development of mental stress.

According to the cognitive load theory6, more complex tasks elicit higher intrinsic CL, which can be reflected in subjective perception of the task, performance, and physiological measures. Subjective perception of CL is usually estimated by self-report surveys used to establish participants’ experiences relevant to different aspects of task performance. A commonly used tool for measuring subjective CL is NASA Task Load Index (NASA TLX) survey7,8, which was successfully implemented in the studies of mental distraction during car driving9 and can be used for validating emerging ways of objective CL detection based on physiological signals, including brain activity, ocular motion metrics, cardiac indices, breathing, and endodermal measures (e.g., temperature, galvanic skin response)7. HR and heart rate variability (HRV) indices are known to be among the most sensitive to changes in CL levels10.

Simulation studies report higher HR in conditions when CL is increased. A consistent elevation in HR was demonstrated for driving with an additional working memory task (the “n-back” task) of increasing difficulty11,12, mental distraction when engaging in conversation while driving13,14, and driving under time pressure enforced by repeated prompts from a passenger15. It was also shown that HR reflects systematic variations in CL during on-road driving16 and that the pattern of changes in HR induced by an additional task is highly consistent between simulated and on-road driving, with the difference that HR was generally higher during on-road driving indicating higher arousal17.

Authors report that HR has greater sensitivity to discriminating the levels of CL during non-challenging highway driving, compared to driving performance metrics, such as lane position, velocity, and steering11,12,14,18. HR was also shown to be more reliable than driving performance metrics over time12. Moreover, HR changes associated with increased CL can be detected prior to declines in driving performance11. It is worth noting, however, that these studies used a simple highway driving environment, and performance metrics may be more sensitive to changes in CL in more complex environments, such as urban.

A recent meta-analysis of cardiac measures of CL19 concludes that various HRV indices are sensitive to changes in CL, but the experimental design, task type and other variables should be considered in the selection of the most appropriate metrics. Typically, elevation of CL leads to a decrease of the time domain measures20, as well as a decrease of the spectral powers of LF (low frequency, 0.04–0.15 Hz) and HF (high frequency, 0.15–0.4 Hz), while the LF/HF ratio increases10. Lenneman and Backs’ driving simulation study18 showed reduced respiration sinus arrhythmia (RSA) when CL was increased by the n-back task. They observed that the decrease in RSA correlated with increased breathing rate, but it was not entirely determined by breathing.

Non-linear HRV analysis has not been frequently applied in the studies of CL. Trutschel et al.21 found a correlation between Poincaré plot SD2 and performance metrics in a night driving task: SD2 increased when performance decreased with lower mental workload and fatigue. Delliaux et al.22 observed a decrease of SD1 and SD2 at the beginning of a long duration switching task (not involving driving), which returned to the control levels by the end of the task; they also report that the correlation dimension (D2) was the best predictive parameter of CL in their task among all time- frequency- and non-linear domain indices.

Additionally, there are some demonstrated gender- and age-related differences in driving performance23,24,25,26,27, subjective perceptions of CL28, and the dynamics of cardiac indices29,30. For example, women are shown to often drive slower than men25,26. Older individuals usually drive slower, exhibit slower reaction times and reduced lane deviation during rapid response to sudden stimulation25, and HRV reduces with age29,30. At the same time, Mehler and colleagues showed that HR reflected CL variations during driving in three age groups: 20–29, 40–49, and 60–69 years old that included both genders, and they did not observe any age-related differences in HR in their sample, concluding that age should not affect CL detection based on HR and individual differences override age-related differences in how well HR reflects CL levels16. Further research on larger samples is needed to verify how much impact gender and age factors may have on HR dynamics related to CL during driving.

Thus, multiple studies demonstrate that increased CL during driving is generally associated with higher HR and lower HRV. However, it is still not clear how accurately CL can potentially be estimated using HR and HRV metrics and what factors may contribute to achieving reliable CL detection. In this work, we attempted to overcome some of the limitations of previous studies of CL by collecting a large dataset representative of the general population in relation to gender, age, ethnicity and driving experience; and by designing conditions that include increase in CL related to driving (simple highway environment versus complex urban environment requiring navigation) and mental distraction (the n-back task). The goals of the study were: (1) to estimate how accurately HR and HRV indices can differentiate between conditions with different CL levels, and (2) to check whether gender and age factors have noticeable effects on accuracy.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 1197 drivers who volunteered to take part in this study and completed it. A final sample of 892 participants (44% female, age from 18 to 79 years old: M = 41, SD = 14) was selected for analyses based on their n-back task performance (at least 50% correct response rate was considered as adequate performance, see the n-back task description below and Supplementary Table S1). The selected participants identified as of European (49%), Asian (16%), African (12%), Indian (12%) or Hispanic (11%) ethnic groups, reported driving experience between 1 and 45 years and that they drive regularly, at least once a week. All participants reported they were healthy, neurologically normal, not currently taking any psychoactive medication, had normal-to-corrected vision, including no colour-blindness, Russian or English speakers (all instructions and explanations were given in participant’s language). All the participants were paid 20–100$ (depending on the region where the experiment was conducted: Russia, Armenia or the USA) and gave an informed consent. The experimental protocols were approved by the ethical committee of the Yerevan State University (Yerevan, Armenia), adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines, and were implemented in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental procedures

All experiments took place between 8am and 6pm. Prior to the experiments, participants were asked to ensure: a normal for them amount of night sleep before the experiment; not to have food or drinks containing caffeine for at least 2 h prior to the experiment; not to take any medications causing drowsiness for at least 8 h before the experiment; not to consume any alcohol for at least 24 h prior to the experiment; not to smoke or engage in vigorous physical activities for at least 2 h prior to the experiment.

At the beginning of each experiment, the participants were asked to complete questionnaires gathering information on quality of their last night sleep, caffeine and alcohol consumption, and taking any medication that could affect driving performance. Participants’ blood pressure was measured, and if it was outside the range of 90/60–150/100 mmHg, experiments were cancelled. This ensured that participants were in good health and not overly stressed or anxious prior to the experiments. They also responded to a CL questionnaire (NASA TLX, see the details below) before driving. Then participants were asked to proceed and sit down in the driving simulator.

Driving simulation

The experiments were conducted in a fixed-base driving simulator developed using BeamNG.py library (BeamNG.tech). It included conventional in-vehicle equipment: driver’s seat, steering wheel, and pedals (accelerator and brake, as in automatic transmission). A computer with high processing capability was synchronised with the simulator to record participants’ steering activity and vehicle location on x, y, and z-axis. The simulator generated images on three LED monitors located in a 180o semicircle around the participant at the distance of approximately 1120 mm. Temperature and lighting were controlled (19–21 °С, 80–100 lx). In-vehicle acoustic environment was simulated using standard BeamNG sound-effects. In cases of an accidental damage to the simulated vehicle, it was forcibly stopped and reinitiated from the last checkpoint where the participant would continue driving.

At the beginning of the experiment, participants were given an opportunity to familiarise themselves with the simulator environment by completing a training driving task for about 3–5 min. Then the main experiment began.

Experimental design

The experiment was designed to create stages with different amount of CL administered during driving. One factor affecting CL is complexity of the road environment. The simulator was equipped for two types of driving scenarios: highway and urban. In the simple highway scenario, the road environment was desert-like and flat, with no traffic or other disturbances. Participants were instructed to drive the vehicle respecting the speed limit and traffic rules. In the urban scenario, a standard city environment with traffic was simulated. Participants were instructed to drive the vehicle along the route indicated by red markings on the road while respecting the speed limit and traffic rules. Thus, the urban scenario was a more complex environment, modelling a higher CL condition, compared to the highway scenario. There was no special feedback on driving errors. The speed limit in both scenarios was 45 mph (72 km/h).

The n-back task

The amount of CL administered during driving can also be manipulated by adding a secondary task that is unrelated to controlling and directing the vehicle. In this study, we used a modified version of the auditory-verbal n-back task31. The modification to this task included an introduction of a response button on the steering wheel, instead of a verbal response. This was done to minimize the physiological signal interference caused by participants’ verbal response11. In each n-back task, participants listened to a pre-recorded series of 10 letters, separated by approximately 2.5-second intervals, for an overall duration of approximately 25 s. The difficulty of the n-back task was varied within each session in order to model naturalistic conditions when the level of CL fluctuates and is not maintained at the same level for the whole duration of the task. With a view of using this data for developing algorithms and models estimating CL levels in the future, we varied task difficulty to avoid overfitting such solutions to a constant level of CL. Thus, there were three levels of the n-back task within each session:

1-back, participants were asked to press the button (built into the steering wheel) each time when two identical letters appeared back-to-back (e.g., DD).

2-back, participants were asked to press the button each time when two identical letters appeared in pairs separated by one letter in between (e.g., DTD).

3-back, participants were asked to press the button each time when two identical letters appeared in pairs separated by two letters in between (e.g., DTAD).

In a 5 min driving stage, 1-, 2- and 3-back tasks were combined sequentially: first, 1-back was presented twice, then 2-back was presented twice, and, finally, 3-back was presented once. An automated announcer repeated the short instruction to the participant before each task. The scheme of the n-back task sequence in driving stages is presented in Supplementary Fig. S2. Only participants with over 50% correct responses to the n-back task were selected for analyses.

Thus, the main experiment contained four 5-minute stages designed to administer different amounts of CL: Urban driving (Urban); Highway driving (Highway); Urban driving with the n-back task (Urban + Nback); and Highway driving with the n-back task (Highway + Nback).

Each of the four 5-minute stages only took place once and was not repeated. The order of the driving stages was randomised for each participant to avoid order-induced bias. The total distance traveled within the experiment was ~ 22 km.

Thus, the levels of CL were modelled in the driving task as follows: (1) CL level during urban driving is higher than during highway driving (Urban > Highway), (2) CL level is higher in stages of driving with simultaneous n-back task, compared to driving without additional tasks (i.e., Urban + Nback > Urban, and Highway + Nback > Highway).

CL questionnaire

Subjective CL ratings were collected using adjusted NASA Task Load Index (NASA TLX) survey7,8. We used these subjective ratings to validate CL levels administered in the stages of driving. After completing each of the driving stages, participants responded to six questions on a 9-point Likert scale, ranging from “very low” (-4) to “very high” (+ 4). The survey was presented on a tablet screen mounted next to the driver’s seat. The following questions within the NASA TLX were used:

(1) How mentally demanding was the driving? (Mental demand scale).

(2) How physically demanding was the driving? (Physical demand scale).

(3) How hurried or rushed was the decision making during the driving? (Temporal demand scale).

(4) How successful were you in accomplishing the driving? (Performance scale).

(5) How hard did you have to work to accomplish your level of performance of the driving? (Effort scale).

(6) How stressed, irritated, and annoyed did you feel while performing the driving? (Frustration scale).

Heart rate recording and analysis

ECG was recorded using a BioHarness 3.0™ (Zephyr Technology, Medtronic, Annapolis, USA) telemetry system with the sampling rate of 1000 Hz. Inter beat intervals (IBIs), defined as time (msec) between consecutive R peaks in QRS complex, were extracted from the ECG signal and exported to custom made Python routines. A set of rules was applied to raw IBI data to screen for artefacts. Abnormal IBIs were identified using an algorithm that applied a combination of absolute, differential, and relative thresholds within sliding windows of varied length (for details, please, see Supplementary Methods S3). 3.7% of raw heart rate data was marked as abnormal and excluded from the analyses.

Selected time-, frequency- and non-linear domain metrics were computed within rolling windows with a 1 s step through each experimental stage. Only windows free of any artifacts were included into this analysis. We calculated mean values for IBIs (Mean IBI, msec) within each window as a measure of the heart rate. HRV indices were computed for the same windows. The standard deviation of the time between normal beats (SDNN, msec) and the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD, msec) were selected as time-domain HRV measures. The power of heart rate variability time series was measured in the low (LF; 0.04–0.15 Hz) and high (HF; 0.15–0.6 Hz) frequency bands, and LF/HF ratio was calculated. LF and LF/HF were only computed for 100 s windows (please, see below). Permutation Entropy (PermEn)32and Sample Entropy (SampEn)33 were calculated as non-linear domain HRV measures. These entropy measures were selected as the most appropriate for short-term analysis among nonlinear HRV features. SampEn (m, r, N) is the negative natural logarithm of the conditional probability that two vectors that are similar for m points remain similar at the next point, where self-matches are not included in calculating the probability. The parameters were: m = 2, r = 0.2×SDNN. PermEn (τ, m, N) is based on computing the Shannon entropy of the relative frequency of all the ordinal patterns found in a time series. The parameters τ and m were: τ = 1 and m = 3. For both entropy measures, N was 30 or 90, depending on the window size.

Time- and frequency domain HRV metrics were calculated within 30 s and 100 s windows. As the entropy metrics are sensitive to the length of the time series, we computed PermEn and SampEn for windows of 30 and 90 IBI sequences. Thus, we had two short windows of analysis – 30 s and 30 IBIs, and two longer windows of analysis – 100 s and 90 IBIs. The metric values were aggregated for each experimental stage per participant and the median values were compared between the stages.

In addition, we performed stress labelling on recorded IBI data. Episodes of acute stress during each of the driving stages were identified by two experts who independently marked such events based on a specific pattern in the dynamics of IBIs that fit the criteria of rapid 30% decrease in IBI length and significant drop in HRV (for more details, please see Supplementary Methods S4). The labelled data was used to calculate the number of experiments for each of the driving stages that contained at least one episode of acute stress.

Accuracy in distinguishing CL levels

All collected HR and HRV metrics data were contrasted between the stages with lower and higher CL: Highway versus Urban; Highway versus Highway + Nback; Urban versus Urban + Nback.

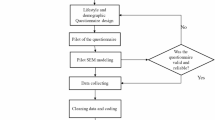

Accuracy in distinguishing CL levels was calculated as shown in Fig. 1. As described above, the metric values were calculated for each window of analysis. For each metric, a value in each window within one driving stage was compared with values in all windows for the stage of comparison. If an absolute difference between the values in two windows fit the expected dynamics, this comparison counted as 1, otherwise 0. What dynamics was expected had been established based on the literature and supported by our own results on subjective CL as well as the results of HR and HRV analyses, please see Results section for more detail. Thus, within-subjects accuracy was calculated for each experiment separately as the sum of compared pairs with expected difference divided by the total number of such comparisons. Accuracy values could be in the range between 0 and 1, with values above 0.5 and closer to 1 indicating higher accuracy.

Between-subjects accuracy was calculated the same way but across all subjects. First, a random sample of windows per stage was selected for each participant, to ensure equal contribution from each recording independent of its length. For shorter windows (30 s and 30 IBIs), 100 windows per stage were randomly selected, and, for longer windows (100 s and 90 IBIs) 40 windows per stage were randomly selected. Then randomly selected windows from all subjects per stage were compared with all randomly selected windows from all subjects in the stage of comparison. Between-subjects accuracy was calculated as the sum of compared pairs with expected difference divided by the total number of comparisons.

Statistical analyses

Open-sourced python SciPy library was used for Statistical analyses. Distributions of variables were tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilks test. Non-parametric tests were performed for rank scale variables. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare conditions of driving within subjects. Association coefficient (r) computed as the effect size for non-parametric tests. Paired t-tests were used to compare HR and HRV values between two conditions with higher and lower CL within sample. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient used for analysis of relationships between variables. Alpha level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests and in all pairwise comparisons. Effect size calculated as Cohen’s d.

Results

Self-reports: NASA TLX scales

Non-parametric tests were used for NASA TLX data because it contained responses on a scale. Responses to frustration, mental, physical, temporal, performance and effort scales of NASA TLX were compared between the pairs of experimental stages. Significant differences (Wilcoxon test) were observed for all compared conditions (Supplementary Fig. S5). Within the sample, NASA TLX ratings across all scales showed greater demand in stages with higher CL, i.e., urban driving was rated as more demanding than highway driving, and driving with an additional n-back task was rated as more demanding than driving without additional tasks. These results show that CL stages modelled in our study were indeed perceived by participants as intended in the experimental design. The performance scale was the best at discriminating the experimental stages (Supplementary Results S6). Participants’ ratings on the frustration scale, which estimated how stressed, irritated and annoyed they felt, were particularly high for the Urban + Nback stage, and very low for the Highway stage (Supplementary Results S5).

HR and HRV metrics dynamics

Descriptive statistics for the HR and HRV metrics is shown in Table 1. Shapiro-Wilks test showed that distributions of values for all metrics were significantly different from the normal distribution (see Supplementary Table S7), therefore median and quartiles are presented along with the mean and standard deviation values5.

Paired t-tests revealed significant differences between the metrics distributions, as shown in Table 2 (all comparisons) and Fig. 2 (for metrics in short windows). Mean IBI was consistently lower in stages with higher CL in both types of window length, indicating higher HR. RMSSD showed similar results, i.e. was lower in stages with higher CL, but there was no significant difference for the urban stages. SDNN was higher in the urban driving stage, compared to highway, which was opposite to expected, but lower for stages with the n-back task, compared to driving without additional tasks. No significant difference was observed for HF. PermEn was consistently higher in stages with higher CL. SampEn was lower in urban stages, compared to highway, but the n-back task was associated with an increase in SampEn. Thus, Mean IBI, RMSSD, and PermEn displayed a uniform dynamic, i.e., consistently decreased or consistently increased in stages with higher CL. These metrics were selected for further analysis of discriminative accuracies.

Additionally, we calculated how many participants experienced at least one episode of acute stress during each of the driving stages. Prior to the experiments situational anxiety was measured, and the majority of the sample (90%) had low to moderate levels of anxiety (Supplementary Results S8). Although we did not intentionally trigger stress, high CL in our task created conditions for some people to experience it. There were just a small number of such cases in highway driving: 2% in Highway and 6.5% in Highway + Nback. Acute stress episodes were much more frequent during urban stages: 21% in Urban stage and 30% in Urban + Nback stage.

Mean IBI, SDNN, RMSSD, HF, PermEn and SampEn calculated for shorter windows of analysis (30 s for time- and frequency- or 30 IBIs for non-linear domain metrics) within the four driving stages. Mean values +-2SE are shown. Mean IBI and RMSSD are consistently lower and PermEn is consistently higher in driving stages with increased CL: Highway vs. Highway + Nback, Urban vs. Urban + Nback, and Highway vs. Urban. Paired t-test, **p < 0.001, *p < 0.01.

Discriminative accuracy of HR and HRV metrics

Within-subjects accuracy

Accuracy for each subject was calculated for windows of analysis so that each metric value in a window was compared with values in all other windows for the stage of comparison; thus, for each experiment and pair of stages, we had a total number of window pairs and the number of window pairs with expected difference. The expected difference was defined based on the results reported above, i.e., lower values in stages with higher CL for Mean IBI and RMSSD, and higher values in stages with higher CL for PermEn. Accuracy for each subject was calculated as the sum of pairs with expected value difference divided by the total number of pairs.

Median values of within-subjects’ accuracies for discriminating between different stages of driving are presented in Table 3. Distributions of within-subjects’ accuracies are shown in Fig. 3. Mean IBI showed the best within-subjects accuracy estimates. Mean IBI worked best at discriminating CL levels between the two road types (Highway vs. Urban) as well as its increase with an additional task (Highway vs. Highway + Nback and Urban vs. Urban + Nback).

Between-subjects accuracy

Between-subjects accuracy was calculated by comparing samples of metrics in a set of random windows from one stage with samples of metrics for the stage of comparison across all participants. Between-subjects accuracy was calculated as the number of comparisons with expected difference, i.e., higher values for PermEn and lower values for the rest of the metrics in higher CL stages, divided by the total number of comparisons.

As it can be observed from Table 4, between-subjects accuracy values are lower than within-subjects accuracy, which is typical for this kind of studies due to individual differences within the sample. However, even in this large and diverse sample most accuracy values are above 0.5 and reflect the expected CL dynamics.

Gender and age effects

Lastly, we tested for gender and age effects on within-subjects accuracy values for Mean IBI and HRV indices within 30 s windows (Supplementary Fig. S9). CL induced by the n-back task was estimated by Mean IBI more accurately in men, compared to women (Mann-Whitney U test, Highway vs. Highway + Nback: U = 89540, p < 0.05; Urban vs. Urban + Nback: U = 86969, p < 0.01). However, when comparing conditions of highway and urban driving, the accuracy was higher for all metrics in women (Mann-Whitney U test, for Mean IBI: U = 122263.5, p < 0.001, and for RMSSD: U = 122137, p < 0.001). This corresponds well with the results obtained from self-reports: NASA TLX ratings for task demand during urban driving were consistently higher in women, compared to men, while no such gender difference was observed for highway driving (Supplementary Table S10), which suggests that urban driving could be more challenging for women.

We found that, in line with the known developmental trends, older participants in our sample had lower HRV (Spearman correlation between age and RMSSD, r = -0.40 during urban driving and r = -0.45 during highway driving) but Mean IBI did not correlate with age (Spearman r < 0.1). To check for age effects, we split the sample into three groups: 18–34 years old, 35–54 years old, and 55 + years old. For Mean IBI, there was no difference between the groups in accuracy values for Highway vs. Highway + Nback comparison (Kruskal-Wallis test, H(2) = 0.795, P = 0.672 ), but accuracy for Urban vs. Urban + Nback was significantly lower in older participants (Kruskal-Wallis test, H(2) = 16.2, P < 0.01). At the same time, accuracy was higher in older participants for Highway vs. Urban driving comparison (Kruskal-Wallis test, H(2) = 39.25, P < 0.001). Similarly, HRV accuracy was lower in older age group in Highway vs. Highway + Nback (RMSSD: H(2) = 7.78, P < 0.05) and Highway vs. Urban comparisons (RMSSD: H(2) = 7.92, P < 0.05). This again corresponded to self-reports: older participants perceived urban driving as more demanding, compared to younger groups (Supplementary Table S11).

Finally, women in all three age groups were more likely to experience episodes of acute stress during urban driving stages than men (Supplementary Table S12), which is in line with the observed differences in their cardiac dynamics and subjective self-reports.

Discussion

This large-scale study was designed to explore how well CL levels can be estimated during driving using HR and HRV indices in short windows of analysis that could potentially allow continuous CL monitoring and acute stress detection. We collected data from 1197 drivers of both genders, different age groups and ethnicities, and, to our knowledge, our final sample of 892 individuals is the largest dataset of its kind. The results of the performed analyses have shown that, in line with previous studies (see Introduction), driving in more demanding conditions (complex urban environment as opposed to simple highway environment) and with a mental distraction from an additional n-back task were accompanied by shorter IBIs, indicating increased HR, and decreased HRV, as measured by RMSSD. The HRV complexity measure, PermEn, consistently increased in stages with higher CL. The observed dynamics of HR, RMSSD and PermEn was used to estimate accuracy that is potentially possible to achieve in differentiating between short windows of data recorded in different CL conditions. HR was shown to be the most robust cardiac measure of CL, with median within-subjects accuracy between highway and urban driving stages of 0.94. Such high accuracy is an especially valuable result considering the size and diversity of our sample. In addition, although we did not specifically trigger it, 30% of the participants experienced at least one episode of acute stress in the highest CL condition while driving. This illustrates that high CL should be considered as a potential factor contributing to the development of acute stress on road. Finally, we observed some gender- and age-related differences in how accurately the selected cardiac measures distinguished between CL conditions, and these differences were corresponding to subjectively perceived demand: women and older individuals found it harder to drive in urban environment than men and younger age groups and their accuracy estimates between highway and urban driving were higher.

The relationship between CL and cardiac dynamics measured by HR and HRV indices is argued to be indirect10,34. An increase in CL leads to blood pressure elevation, which in turn decreases the HRV34. In addition, HRV dynamics depends on respiration and higher CL is associated with higher respiratory frequency (e.g., see review by Grassmann and colleagues35), which also contributes to a decrease in HRV. Rises in CL elevate arousal increasing HR, and, as arousal levels grow, the sympathetic influence of the autonomic nervous system increases while the parasympathetic influence decreases. Thus, the effects observed in our study for HR and RMSSD are in line with expected physiological dynamics.

While our results for RMSSD are in line with the initial hypotheses and conclusions from previous studies, we did not observe such a uniform pattern for SDNN: it was lower in stages with the n-back task, as expected, but it tended to be higher during urban driving, compared to highway driving. Although SDNN generally requires longer window lengths, there are studies that demonstrated its applicability to shorter recordings, such as 30 s36. However, SDNN is known to be influenced by lower frequency bands of HRV and when these bands have greater power than HF, they contribute more to SDNN values37 making it less powerful and consistent for measuring HRV in short windows. In our experiments, urban driving is accompanied by increased HR, as compared with highway driving, indicating higher arousal levels and higher impact of sympathetic activity which is reflected in lower frequency HRV. We believe this explains why SDNN values were generally higher during urban driving. RMSSD is a more appropriate estimate of short-term HRV38, it is highly correlated with HF HRV39 and, therefore, more sensitive to the dynamics of human psychophysiological states corresponding to individual behavior and task-related activities. RMSSD shows reliable results on short recording, such as 10- and 30-second windows36,40 and it outperforms SDNN on ultra-short intervals36.

We did not observe any significant differences for frequency-domain HRV indices. Frequency analyses are more powerful for longer window lengths, even HF is normally computed on data longer than 60 s37.

HRV complexity, as measured by PermEn, was shown to increase with higher CL. Entropy HRV indices estimate nonlinear and non-stationary characteristics of cardiac regulation which are different to stochastic and periodic regulation assessed by time- and frequency domain metrics. Therefore, increases in HRV complexity may reflect adaptations required for functioning under higher CL. This is in line with the view that non-linear, entropy HRV indices reflect complexity of the organization of behavior40,41, partly due to cortical regulation of cardiac activity and the functional heart-brain interactions (e.g., see review by Mazzola and colleagues42). Thus, HRV complexity is usually expected to be higher in more detailed and cognitively challenging behaviors, which is indeed in agreement with our results.

Although stress and its interaction with CL was not the focus of our study, we believe that in the context of CL monitoring it is important to note that while such measures as RMSSD reduce in both high CL and stress conditions, measures of HRV complexity, such as PermEn, may have a different dynamic, i.e., increasing with growing CL but decreasing during acute stress. Generally, measures of HRV and HRV complexity are reduced during stress episodes43. Lower accuracy values for PermEn during urban driving may, in part, be related to more frequent episodes of stress during these driving stages. Further research into the interplay between the dynamics of HRV and HRV complexity may contribute to more accurate CL estimation and stress prediction.

We used the observed dynamics of HR and HRV indices within short windows of analysis to estimate how accurately CL levels can be distinguished between different conditions. HR was shown to be the most robust cardiac measure of driving-related CL when comparing highway and urban conditions (median within-subjects accuracy of 0.94). HR was also the best measure of mental distraction during simple highway driving (median within-subjects accuracy of 0.85). Distinguishing mental distraction during urban driving, where CL is already elevated by driving-related demands, was a more challenging task (median within-subjects accuracy of 0.6) and requires further research into possible approaches to increase the accuracy. One of them may include combining HR with HRV indices or with metrics from another modality, such as eye gaze. We understand, however, that using more signals in combination may also add noise and increase probability of errors. In application to cardiac dynamics, we know that HR is a more reliable and robust measure which is less prone to noise and artifacts, compared to HRV indices. Therefore, we believe an intellectual hierarchy of metrics with assigned weights may be one direction to explore in future work on a model for CL monitoring and stress detection, where HR is considered the base signal with a higher weight. Furthermore, we observed that considering HR and HRV dynamics over time may bring additional insights into changes of physiological states, particularly in relation to CL and stress. We usually expect the increase of HR to be accompanied by a decrease in HRV. However, we often see examples when the HR is not yet increased but the HRV is already declining, and vice versa. Our future research will explore how changing the size of analysis windows may help in utilizing the above trends in order to increase the accuracy, particularly in urban driving.

Additionally, we found effects of gender and age on discriminative accuracy: women and older participants subjectively evaluated urban driving as a more demanding and difficult task, compared to highway driving, and this subjective perception was also reflected in higher accuracy for these demographic groups in distinguishing between urban and highway driving based on all HR and HRV metrics. As discussed in the Introduction, gender- and age-related differences in driving performance23,24,25,26,27, subjective perceptions of CL28, and the dynamics of cardiac indices29,30 are well known and demonstrated in various studies. Our work shows that such differences have an impact on accuracy of differentiating between highway and urban driving based on the dynamics of HR and HRV indices. Individuals who find certain aspects of driving difficult and subjectively perceive them as more challenging have more pronounced changes in their cardiac dynamics which is reflected in accuracy estimates.

Overall, our results show that HR and HRV indices reflect CL levels on short intervals of time, such as 30 s, and could be used for continuous CL monitoring and stress detection. Moreover, the results observed for HR indicate that accurate CL monitoring and acute stress detection can potentially be achieved not only using ECG sensors, but also with the pulse wave signal extracted from wearable and remote photoplethysmography devices. Recent research has successfully utilized variability measures of the pulse wave44, including HRV complexity measures45, which could be used in combination with HR to increase accuracy of CL estimation, especially when CL is already elevated by driving demand, e.g. in urban environments. Taking into account the relationship between high CL and mental stress, we believe this approach can be applied to acute stress detection. HR changes associated with episodes of acute stress are even more pronounced than in case of high CL alone, therefore we expect higher accuracy in acute stress detection based on HR.

Ayres and colleagues10 analysed 33 experiments available in the literature and found that the most sensitive physiological measures of CL were blink rates, HR, pupil dilations, and alpha waves of EEG. Generally, for practical applications, eye gaze measures are considered the most sensitive to changes in CL levels, followed by HR. However, eye gaze is not always available for continuous monitoring. Head turns, sunglasses and other factors in natural environment outside laboratory settings affect how much information is available about eye movements at a time. For practical applications, such as driver monitoring systems, eye gaze can be complimented with solutions utilizing HR, which can also be extracted from video cameras (remote photoplethysmography) or obtained in other ways. We show that HR and HRV are sensitive to changes in CL during driving, and their dynamics can be used for practical applications and monitoring systems, including those that are primarily based on other signals, such as eye gaze, to improve continuity, accuracy, and robustness of such systems.

Conclusion

The results of this large-scale study showed that increased CL was accompanied by higher HR, lower HRV, as measured by RMSSD, and higher HRV complexity, as measured by PermEn. Driving with the highest level of CL in our task triggered episodes of acute stress in 30% of participants. HR displayed the highest accuracy in discriminating between short 30 s windows of different CL conditions, particularly highway versus urban driving and mental distraction during highway driving. These results illustrate that HR and HRV indices provide a valid source for mathematical modelling, including ML/AI applications, aimed at CL monitoring and acute stress detection. High discriminative accuracy of HR suggests that accurate CL and stress detection can potentially be achieved using the pulse wave signal extracted from wearable and remote photoplethysmography devices.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author for academic research and non-commercial use only. Please, provide a detailed description of your research and how you intend to use the data. All requests will be reviewed based on the information provided. Incomplete descriptions will result in delays in granting access.

References

Engström, J., Markkula, G., Victor, T. & Merat, N. Effects of cognitive load on driving performance: The Cognitive Control Hypothesis. Hum. Factors 59, (2017).

Longo, L., Wickens, C. D., Hancock, P. A. & Hancock, G. M. Human mental workload: A survey and a novel inclusive definition. Frontiers in Psychology13 Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883321

Warm, J. S., Parasuraman, R. & Matthews, G. Vigilance requires hard mental work and is stressful. Human Factors 50 Preprint at (2008). https://doi.org/10.1518/001872008X312152

Hjortskov, N. et al. The effect of mental stress on heart rate variability and blood pressure during computer work. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 92, (2004).

Causse, M. et al. Facing successfully high mental workload and stressors: An fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, (2022).

Sweller, J., Ayres, P. & Kalyuga, S. Cognitive load theory [Electronic Resource]. Explorations Learn. Sci. Instructional Syst. Perform. Technol., 1 (2011).

Hart, S. G. NASA-task load index (NASA-TLX); 20 years later. in Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (2006). https://doi.org/10.1177/154193120605000909

Hart, S. G. & Staveland, L. E. Development of NASA-TLX (Task load index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. Adv. Psychol. 52, (1988).

Strayer, D. L. et al. Assessing cognitive distraction in the automobile. Hum. Factors 57, (2015).

Ayres, P., Lee, J. Y., Paas, F. & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. The Validity of Physiological Measures to Identify Differences in Intrinsic Cognitive Load. Frontiers in Psychology vol. 12 Preprint at (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.702538

Mehler, B., Reimer, B., Coughlin, J. F. & Dusek, J. A. Impact of incremental increases in cognitive workload on physiological arousal and performance in young adult drivers. Transp. Res. Rec. https://doi.org/10.3141/2138-02 (2009).

Belyusar, D., Mehler, B., Solovey, E. & Reimer, B. Impact of repeated exposure to a multilevel working memory task on physiological arousal and driving performance. Transportation Research Record vol. 2518 Preprint at (2015). https://doi.org/10.3141/2518-06

Pouyakian, M., Zokaei, M., Falahati, M., Nahvi, A. & Abbasi, M. Persistent effects of mobile phone conversation while driving after disconnect: Physiological evidence and driving performance. Heliyon 9, (2023).

Tejero, P. & Roca, J. Messages beyond the phone: Processing variable message signs while attending hands-free phone calls. Accid. Anal. Prev. 150, (2021).

Rendon-Velez, E. et al. The effects of time pressure on driver performance and physiological activity: A driving simulator study. Transp. Res. Part. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 41, (2016).

Mehler, B., Reimer, B. & Coughlin, J. F. Sensitivity of physiological measures for detecting systematic variations in cognitive demand from a working memory task: An on-road study across three age groups. Human Factors vol. 54 Preprint at (2012). https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720812442086

Reimer, B. & Mehler, B. The impact of cognitive workload on physiological arousal in young adult drivers: A field study and simulation validation. Ergonomics 54, (2011).

Lenneman, J. K. & Backs, R. W. Cardiac autonomic control during simulated driving with a concurrent verbal working memory task. Hum. Factors 51, (2009).

Hughes, A. M., Hancock, G. M., Marlow, S. L., Stowers, K. & Salas, E. Cardiac measures of cognitive workload: A meta-analysis. Hum. Factors 61, 393–414 (2019).

Digiesi, S. et al. Heart rate variability based assessment of cognitive workload in smart operators. Manage. Prod. Eng. Rev. 11, 56–64 (2020).

Trutschel, U. et al. Heart rate measures reflect the interaction of low mental workload and fatigue during driving simulation. in AutomotiveUI 2012–4th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, In-cooperation with ACM SIGCHI - Proceedings doi: (2012). https://doi.org/10.1145/2390256.2390299

Delliaux, S., Delaforge, A., Deharo, J. C. & Chaumet, G. Mental Workload alters Heart Rate Variability, lowering Non-linear dynamics. Front. Physiol. 10, (2019).

Quillian, W. C., Cox, D. J., Kovatchev, B. P. & Phillips, C. The effects of age and alcohol intoxication on simulated driving performance, awareness and self-restraint. Age Ageing 28, (1999).

Lee, H. C., Lee, A. H. & Cameron, D. Validation of a driving simulator by measuring the visual attention skill of older adult drivers. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 57, (2003).

Reimer, B., D’Ambrosio, L. A. & Coughlin, J. F. Secondary analysis of time of day on simulated driving performance. J. Saf. Res. 38, (2007).

Pan, C. et al. Sex difference in driving speed management: The mediation effect of impulse control. PLoS One 18, (2023).

Ferrante, C., Varladi, V. & De Blasiis, M. R. Gender differences measured on driving performances in an urban simulated environment. in Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 958 (2020).

Kim, M. H. & Son, J. On-road assessment of in-vehicle driving workload for older drivers: Design guidelines for intelligent vehicles. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 12, 265–272 (2011).

Zhang, J. Effect of age and sex on heart rate variability in healthy subjects. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 30, (2007).

Garavaglia, L., Gulich, D., Defeo, M. M., Mailland, J. T. & Irurzun, I. M. The effect of age on the heart rate variability of healthy subjects. PLoS One 16, (2021).

He, D., Donmez, B., Liu, C. C. & Plataniotis, K. N. High cognitive load Assessment in drivers through Wireless Electroencephalography and the validation of a modified N-Back Task. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 49, (2019).

Sippel, S., Lange, H. & Gans, F. statcomp: Statistical complexity and information measures for time series analysis. R package version (2016).

Richman, J. S. & Moorman, J. R. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy maturity in premature infants physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Americal J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 278, (2000).

Solhjoo, S. et al. Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability correlate with clinical reasoning performance and self-reported measures of cognitive load. Sci. Rep. 9, (2019).

Grassmann, M., Vlemincx, E., Von Leupoldt, A. & Mittelstädt, J. M. & Van Den Bergh, O. Respiratory changes in response to cognitive load: A systematic review. Neural Plasticity vol. 2016 Preprint at (2016). https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8146809

Munoz, M. L. et al. Validity of (Ultra-)Short recordings for heart rate variability measurements. PLoS One 10, (2015).

Shaffer, F. & Ginsberg, J. P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health 5 Preprint at (2017). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00258

Malik, M. et al. Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. European Heart Journal 17 Preprint at (1996). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014868

Thayer, J. F., Åhs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers, J. J. & Wager, T. D. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 36 Preprint at (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009

Bakhchina, A. V., Arutyunova, K. R., Sozinov, A. A., Demidovsky, A. V. & Alexandrov Y. I. Sample entropy of the heart rate reflects properties of the system organization of behaviour. Entropy 20, (2018).

Arutyunova, K. R., Bakhchina, A. V., Sozinova, I. M. & Alexandrov, Y. I. Complexity of heart rate variability during moral judgement of actions and omissions. Heliyon 6, (2020).

Mazzola, L., Mauguière, F. & Chouchou, F. Central control of cardiac activity as assessed by intra-cerebral recordings and stimulations. Neurophysiologie Clinique 53 Preprint at (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucli.2023.102849

Castaldo, R. et al. Acute mental stress assessment via short term HRV analysis in healthy adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 18 Preprint at (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2015.02.012

Mejía-Mejía, E. & Kyriacou, P. A. Effects of noise and filtering strategies on the extraction of pulse rate variability from photoplethysmograms. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control 80, (2023).

Zhan, J. et al. A fast permutation entropy for pulse rate variability online analysis with one-sample recursion. Med. Eng. Phys. 120, (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all our colleagues and team members who assisted with the organization and implementation of the study. Data collection: Mariya Nevaykina, Mariia Mikhailova, Mikhail Mikhailov, Dmitrii Petrov, Aleksei Churilov, Roman Karimov, Aleksey Chirikov, Viktor Sokolov, Vladimir Borzikov and Boris Petrunin. Software development: Mikhail Sotnikov, Maksim Godovitsyn, Evgenii Krasnopevtsev, Evgenii Stepanov, Davit Hambardzumyan, Aleksandr Tolich, Dmitrii Silin, and Aram Hovhannisyan. Data processing algorithms and analytics: Andrey Shilov, Aleksey Nikolaev, Lilit Yolyan, Anzhela Burova, Nikita Timakin, Roman Vlasov, and Grigory Radchenko. Data flow infrastructure and algorithms: Arsenii Semenov. Organizational support: Irina Astafeva; and other members and partners contributed to the Neurosense project, Harman X, Harman International.

Funding

The research is funded by Harman International, all authors are employed by the company and receive salary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design and implementation of the research. K.R.A., A.V.B., D.I.K. and M.M. analysed the data. K.R.A. and A.V.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed and commented on the results. I.S.S. and A.V.F. supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arutyunova, K.R., Bakhchina, A.V., Konovalov, D.I. et al. Heart rate dynamics for cognitive load estimation in a driving simulation task. Sci Rep 14, 31656 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79728-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79728-x