Abstract

Reports on the application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) in adult patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery remain limited. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of mNGS analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) in such patients.A retrospective cohort study was conducted on adult patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery. Samples were collected from patients in the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital between January 2019 and March 2024. Upon diagnosis of severe pneumonia, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was obtained via bronchoscopy within 24 h. The mNGS group was composed of patients tested using mNGS and conventional microbiological tests. BALF was detected only by the conventional microbiological test (CMT) method in the CMT group, which involved examining bacterial and fungal smears and cultures at least. We reviewed a total of 4,064 cardiac surgeries, and based on the inclusion criteria, a total of 113 adult patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery were included in this study. The overall positive rate detected by mNGS was significantly higher than that of the culture method (98% vs. 58%, P<0.0001). After receipt of the microbiological results, the mNGS group exhibited a higher incidence of antibiotic adjustments in comparison to the CMT group (P = 0.0021). After adjusting the treatment plan based on microbial testing results, the mNGS group showed an improvement in ventilator-free days within 28 days (P = 0.0475), with a shorter duration of invasive ventilation compared to the CMT group (P = 0.0208). The detection of mNGS can significantly improve the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II (APACHE II) score (P = 0.0161) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (P = 0.0076) on the 7th day after admission to the SICU. In this study, the mNGS group showed signs of having a positive impact on the length of stay in ICU (median: 9 days, IQR: 7–10 days vs. median: 10 days, IQR: 8-13.75 days, P = 0.0538), length of stay in Hospital (median: 20 days, IQR: 17–28 days vs. median: 25 days, IQR: 18–29 days, P = 0.1558), mortality in 28 days (19% vs. 20%, P = 0.8794), in-hospital mortality (19% vs. 22%, P = 0.7123); however, statistical analysis did not confirm these differences to be significant. mNGS could serve as a valuable complement to conventional diagnostic approaches in adult patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery, potentially improving diagnostic accuracy and leading to more precise and timely interventions, with significant potential to inform clinical decision-making and enhance patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

severe pneumonia, cardiac surgery, metagenomic next-generation sequencing, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, pathogen.

Introduction

Cardiac surgical patients commonly face elevated infection risks due to conditions such as pulmonary congestion, ischemia-reperfusion injury after cardiopulmonary bypass, cardiac surgery injury, hypothermia, blood loss and malnutrition1,2. These specific risks facilitated the progression of postoperative pulmonary complications. The ensuing hospital-acquired pneumonia, with its profound influence on patient outcomes, can trigger respiratory failure, multi-organ dysfunction, prompting extended intensive care unit (ICU) stays, ventilator time, and overall hospitalization, posing formidable challenges for medical management3,4,5,6,7. Regrettably, diagnosis of these patients’ infections can be complex, as clinical and lab indicators of inflammation result not only from infection but also systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) related to factors such as post cardiopulmonary bypass ischemia reperfusion injury or endotoxin displacement8,9.

Moreover, a significant reason hampering empirical treatment of pneumonia is the pathogen uncertain and mixed infection. Early diagnosis of etiology coupled with effective treatment significantly impacts patient prognosis. Precise identification of these pathogens is the cornerstone of successful anti-infection and treatment10.

Despite conventional microbiological test (CMT) serving as the gold standard for clinical microbe detection, it exhibits limitations including extended detection time, low sensitivity and some pathogenic bacteria could not be cultured8,11. These limitations often render CMTs, such as bacterial and fungal smears and cultures, insufficient for the clinical diagnosis and management of critical patients12,13. In recent years, metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has distinguished itself in pathogen identification. This technology can detect multiple pathogens simultaneously including bacteria, viruses, and fungi with high sensitivity and specificity. Previous research has shown that this method offers a more comprehensive and accurate detection of pathogenic microorganisms compared to CMTs, thereby supporting therapeutic decisions and infection management10,14. Furthermore, an increasing number of rare pathogens are being identified through mNGS, providing critical data for the diagnosis and management of complex, severe cases15,16. Additionally, mNGS provides information for the rapid identification of potential antimicrobial resistance by detecting sequences associated with resistance genes17,18,19.

It is regrettable that despite the extensive literature comparing the diagnostic performance of mNGS with CMTs, there were few real-world clinical studies examining the impact of mNGS of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) on clinical outcomes in patients with severe pneumonia. This is particularly true for specific subgroups such as adult patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery. This study was conducted to compare a comprehensive treatment strategy based on mNGS with a standard treatment based on CMTs, evaluating the impact of mNGS of BALF on the clinical outcomes of patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery.

Materials and methods

Population and study criteria

A retrospective analysis was conducted on adult patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery who were admitted to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital between January 2019 and March 2024. The protocol used in this retrospective study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (No: 2024-30). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all data were anonymous before analysis. After being diagnosed with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery, patients who provided informed consent for mNGS testing, either by themselves or through their authorized representatives, were included in the mNGS group and underwent both mNGS and traditional pathogen detection. Patients who did not consent to mNGS testing were assigned to the CMT group, and their BALF samples underwent only traditional pathogen detection, including at least bacterial and fungal smears and cultures. The diagnosis of severe pneumonia, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) was based on the criteria established by the American Thoracic Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (ATS/IDSA)20,21. Assess the efficacy of treatment by analyzing symptoms, physical examination findings, and laboratory test results20,21.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Adult patients (aged > 18 years) admitted to the SICU with severe pneumonia following cardiac surgery, meeting ATS/IDSA diagnostic criteria. (2) Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) obtained via bronchoscopy within 24 h of severe pneumonia diagnosis. (3) Complete clinical data available.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Death or discharge within 48 h of ICU admission. (2) mNGS performed DNA sequencing only and could only detect DNA viruses. (3) Pulmonary lesions caused by other factors. (4) BALF samples failing mNGS quality control, such as human-origin sequences exceeding 99%. (5) Incomplete required clinical data.

Clinical data and treatment

The clinical data of each participant were collected from hospital electronic medical records, which included: (1) age, gender, past medical history and body mass index (BMI); (2) the surgical method, duration of surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time, aortic cross-clamp time; (3) comorbidities, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, laboratory results. (4) the duration in which the sample resides from submission to etiology results feedback, in the NGS and CMT groups respectively. (5) prognostic information on antimicrobial use, prognostic information on mechanical ventilation, ICU hospitalization, new-onset infection, and 28-day mortality were recorded after surgery.

Before the causative pathogens were identified, clinicians formulated routine diagnoses and treatments based on established guidelines and consensus21,22,23.

we adjusted the antibiotic regimen according to the following principles:

-

(i)

Upon initial antibiotic therapy, if the patient’s inflammatory markers (procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and white blood cell count) decrease, lung imaging improves, and mNGS monitoring shows negative results, then antibiotic regimen can be de-escalated or simplified. De-escalation refers to changing an empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen to a narrower antibiotic regimen by changing the antimicrobial agent or changing from combination therapy to monotherapy20.

-

(ii)

If the patient’s clinical and laboratory indicators improve and the initial antibiotics cover the pathogen, stick to the basic antibiotic regimen.

-

(iii)

If the patient’s clinical and laboratory indicators did not improve and pathogens not covered by the initial anti-infective regimen were detected, we adjusted the antibiotic therapy.

-

(iv)

If the patient’s clinical and laboratory indicators did not improve and the microorganisms detected by mNGS may be resistant, antibiotics were adjusted based on the pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and characteristics of bacterial resistance in our center. The determination of potential pathogen resistance is based on clinical symptom improvement, mNGS results for resistance genes, and the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns specific to our research center.

Sample processing and time of sample submission to results feedback

Bedside bronchoscopy was administered post informed consent by respiratory therapists (RTs). Employing standard methods, RTs harvested > 5 mL protected BALF specimens from patients and placed each sample in a sterile sputum container24,25,26,27.

The time of sample submission to results feedback was recorded based on the timestamp when the BALF samples were logged into the microbiology lab system until the validated microbiological report was issued. This duration included the time required for bacterial and fungal cultures to confirm negative results and was obtained from the hospital information system. For the CMT group, the time of sample submission to results feedback refers to the final report time of the CMTs.

Conventional microbiological test

These were dispatched independently to the microbiology laboratory for routine evaluation, such as bacterial and fungal smears and cultures, acid-fast staining, and polymerase chain reaction for specimens from patients exhibiting suspected viral infection.

CMTs encompass bacterial and fungal smear and culture, acid-fast staining, Gomori methenamine silver staining for Pneumocystis, India Ink Staining Smear Microscopy for Cryptococcus, mycobacterial culture and identification, Gen-Xpert, as well as serological tests of blood including the (1–3)-β-D-Glucan Test (G test), Galactomannan antigen test (GM test), cryptococcal capsule antigen detection, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae antibody detection. Additionally, nasopharyngeal swab and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid PCR are used to detect respiratory pathogens, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Influenza A and B viruses, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and Parainfluenza viruses (Supplementary Information 2, Tables S2.1-S2.2).

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing procedure

Perform wall breaking and centrifugation on BALF samples according to standard procedures. Subsequently, the 600 µL sample was separated into new 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tubes, and the DNA/RNA was extracted using the nucleic acid extraction or purification reagent kit (Genskey, Tianjin) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA libraries were constructed through DNA fragmentation, end repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. The Agilent 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) was used for quality control of the DNA libraries. The quality qualified libraries were sequenced on the MGI-200/2000 platform, with a sequencing length of SE50 and a sequencing data volume of no less than 20 M Reads.

Bioinformatics analysis

The raw data were split using bcl2fastq software, and the connector sequences and low-quality base sequences were removed using fastp software to obtain high-quality and effective data. Sequences from the human genome were removed using the bowtie2 calibration software. Eventually, sequences that could not be mapped to the human genome were retained and the rest of the sequences were aligned to the microbial genome database, which was constructed using the sequences of bacteria, fungi, archaea, and viruses screened in the NCBI database. The microbial genome database contains 12,895 bacteria, 11,120 viruses, 1,582 fungi, 312 parasites, 184 mycoplasmas/chlamydia, and 177 mycobacteria.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0.0(121) (GraphPad Software, LaJolla, CA, USA). The normally distributed data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were compared between groups by t-testing. Nonnormally distributed data are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) and were compared by Mann Whitney test. P values of < 0.05 were considered to denote the statistical significance.

Results

Demographic characteristics

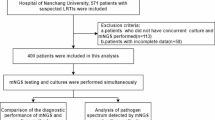

From January 2019 to March 2024, our institution conducted 4,064 cardiac surgeries, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Among these surgeries, we identified 162 adult patients with severe pneumonia for potential inclusion in the study. Following the application of our exclusion criteria, 49 patients were deemed ineligible (Fig. 1). The reasons for exclusion included: 17 patients either passed away or were discharged within the first 48 h post-admission to the SICU; 30 patients underwent mNGS that was limited to DNA sequencing, thus only capable of detecting DNA viruses; and 2 cases where the pulmonary lesions were determined to be due to alternative etiologies (Fig. 1). Finally, this study included a total of 53 patients in the mNGS group, with an additional 60 patients allocated to the CMT group (Fig. 1). Patient demographics, characteristic baselines, and ICU special treatments in the mNGS and CMT groups were shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Information 3. Table S3.1. There were no significant differences in age, gender, BMI, types of cardiac surgery, duration of surgery, CPB time, aortic cross-clamp time between both groups (P > 0.05). It is worth noting that the mNGS group had a lower oxygenation index and higher APACHE II, SOFA, and vasoactive inotropic scores (VIS) compared to the CMT group before treatment (P<0.05).

Comparison of mNGS and CMT results

shows the distribution of pathogens detected by mNGS and CMT in this study. The most commonly detected pathogenic bacteria were Klebsiella pneumoniae in both groups, Acinetobacter baumannii complex being ranked second. Among the 53 patients in the mNGS group, a total of 53 mNGS tests were conducted, with 52 (98%) testing positive for mNGS, with only one patient having a false-negative result (Fig. 2). Conversely, in the CMT group, only 35 out of 60 patients (58%) had positive results (Table 2, P < 0.0001). Additionally, the total number of pathogens identified in the mNGS group was significantly higher compared to the CMT group (P < 0.0001). Furthermore, Pneumocystis jirovecii, Aspergillus flavus, Mycoplasma salivarium, Mycobacteroides abscessus, Human betaherpesvirus 7 and Human alphaherpesvirus 1 were detected only in the mNGS group. (Additional information: The distribution and resistance patterns of traditional cultured pathogens for all ICU patients during the study period are detailed in Supplementary Information 1.)

Treatment and prognosis

The etiology results and treatments of patients in the mNGS and CMT groups are compared in Table 2. The median time from sample submission to results feedback was significantly shorter in the mNGS group (22 h, IQR 18.0-24.5) compared to the CMT group (67 h, IQR 56.5–83.0; P < 0.0001). Antibiotic adjustments were more frequently done in the mNGS group with 62% versus 33% in the CMT group (P = 0.0021). De-escalation or simplification of antibiotic therapy was performed in 15% of cases in the mNGS group as against 3% in the CMT group, which was statistically significant (P = 0.0280). Furthermore, new antibiotics were added or the current antibiotics were upgraded in 47% of the mNGS group compared to 25% of the CMT group, also showing a significant difference (P = 0.0139).

After adjusting the treatment plan based on microbial testing results, the mNGS group showed an improvement in the APACHE II score (P = 0.0161) and SOFA score (P = 0.0076) on the 7th day after admission to the SICU (Table 3). This suggests a better physiological status and organ function at 7 days post-intervention in the mNGS cohort. Additionally, the mNGS group showed an improvement in ventilator-free days within 28 days (Table 3; P = 0.0475), with a shorter duration of invasive ventilation compared to the CMT group (Table 3; P = 0.0208).

In this study, the mNGS group showed signs of having a positive impact on length of stay in ICU (9 vs. 10, P = 0.0538), length of stay in Hospital (20 vs. 25, P = 0.1558), mortality in 28 days (19% vs. 20%, P = 0.8794), in-hospital mortality (19% vs. 22%, P = 0.7123); however, statistical analysis did not confirm these differences to be significant (Table 3).

Discussion

The pathogenic spectrum of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

In this study, mNGS was employed to identify the causative pathogens of pneumonia following cardiac surgery. For patients who have undergone cardiac surgery, our study revealed that Gram-negative bacteria, particularly Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii complex, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus influenzae and Escherichia coli are the major causes of HAP (Fig. 2), which is consistent with previous studies that utilized traditional culture methods28,29. This indicates that Gram-negative bacteria may be the first pathogen to be considered after cardiac surgery. It is noteworthy that the application of mNGS technology has provided a deeper insight into the microbial landscape of post-cardiac surgery pneumonia, uncovering rare novel pathogens that might elude detection through traditional culture methods, such as Pneumocystis jirovecii, Cryptococcus neoformans, and viruses (Fig. 2). This advancement suggests that mNGS could serve as a valuable complement to conventional diagnostic approaches, potentially leading to more accurate and timely interventions.

The impact on clinical outcomes

This study, the first of its kind, was conducted to compare a comprehensive treatment strategy based on mNGS with a standard treatment based on CMTs, evaluating the impact of mNGS of BALF on the clinical outcomes of patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery. Our study has provided evidence of clinical improvement effect of mNGS with a BALF sample in adult patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery.

First, mNGS was faster. The median time from sample submission to result feedback was significantly shorter in the mNGS group (22 h, IQR 18.0-24.5) compared to the CMT group (67 h, IQR 56.5–83.0; P < 0.0001). In addition, mNGS demonstrated excellent sensitivity for pathogen detection in adult patients with severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery. The significant difference in positive detection rates between mNGS and CMT methods underscores the potential of mNGS to revolutionize the diagnostic process for infectious diseases in the clinical setting. Adjusting the treatment plan based on microbial testing results may be associated with improved early clinical outcomes compared to CMT, as evidenced by statistically significant results in critical early markers, such as APACHE II and SOFA scores at 7 days post-intervention, and respiratory support requirements. However, these benefits did not translate into statistically significant differences in mortality rates or the overall length of hospital stay. This finding is consistent with the results of Yang et al. 2022, who reported a similar improvement in severe hospital-acquired pneumonia but no improvement in medium- or long-term survival, especially in patients with severe comorbidities30. Additionally, a recent multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigating the impact of mNGS on clinical outcomes in ICU patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia (SCAP) demonstrated that mNGS combined with CMTs significantly reduced the time to clinical improvement within 28 days compared to CMTs alone31. These results suggest that mNGS can enhance clinical management and outcomes in critically ill patients by enabling more accurate and timely adjustments to antimicrobial therapy. However, our findings appear to contrast with those reported by Zhang et al. 2020 and Xie et al.2019, who found that the 28-day mortality rate of the NGS group was significantly lower than that of the CMT group (P < 0.05)32,33.

Several factors might account for the discrepancies observed between these studies. First, given that this is a retrospective study, the baseline values of the mNGS group were associated with higher APACHE II and SOFA scores, as well as increased respiratory support efforts. Previous studies have shown that the higher the APACHE II and SOFA scores of sepsis patients, the worse the prognosis, which may potentially mitigate the benefits derived from mNGS in this study34,35,36. Second, when discussing the current research landscape in this field, it is crucial to acknowledge that existing studies are predominantly retrospective in nature. They are characterized by small sample sizes and significant heterogeneity among study populations. This heterogeneity presents a particular challenge in drawing broad conclusions. Specifically, our study focused on patients who developed severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery, in contrast to other studies which have included all patients with severe pneumonia regardless of the underlying cause. This distinction is critical as it suggests that findings from our research might reflect unique aspects of postoperative complications and management, differentiating it from the broader category of severe pneumonia. Further studies with larger patient populations and different clinical settings are necessary to validate these findings and assess their generalizability.

Pathogenic determination and clinical decision-making with mNGS

The mNGS was previously recognized as too sensitive for identifying microbes, and thus could lead to overuse of antibiotics. On the other hand, mNGS does not allow us to precisely differentiate between microbiome, colonizers, flora and pathogenic overgrowth31. However, mNGS results must be interpreted alongside the relative abundance of detected organisms, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics to accurately identify the causative microorganism.

Among the patients tested, Human betaherpesvirus 7 was detected in 13.3% of cases, Epstein-Barr virus in 10.6%, and Human betaherpesvirus 5 in 8.8%. However, interpreting the detection of Human betaherpesvirus 7, Epstein-Barr virus, and Human betaherpesvirus 5 requires caution to prevent overtreatment. Our study employed a combination of clinical correlation, quantitative analysis, and immune status assessment methods to distinguish between active infections and bystander activation37.

In this study, we found that in the mNGS group, 47% of patients required the addition or escalation of antibiotics. This high percentage is primarily attributed to the detection of various potentially resistant pathogens and rare microorganisms. Specifically, newly identified pathogens not covered by the initial antibiotic spectrum included Aspergillus fumigatus (4 cases), Enterococcus faecium (2 cases), Corynebacterium striatum (1 case), Aspergillus flavus (1 case), Cryptococcus neoformans (1 case), Legionella pneumophila (1 case), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (1 case), and Pneumocystis jirovecii (1 case). Additionally, potential antimicrobial resistance genes were noted in pathogens such as Klebsiella pneumoniae (4 cases), Acinetobacter baumannii complex (3 cases), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (3 cases), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (3 cases). The high sensitivity and specificity of mNGS facilitated the rapid detection of these pathogens, which might have been delayed or missed by CMT. This rapid optimization of anti-infective treatment resulted in significant improvements in the 7-day APACHE II score, SOFA score, and 28-day ventilator-free days in the mNGS group. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies. For instance, a study on severe pneumonia following pediatric congenital heart surgery demonstrated that the number of antibiotic adjustments in the mNGS group was significantly higher than that in the CMT group (70% vs. 35%, P < 0.05), and the proportion of pulmonary infections that improved after adjustment was also significantly higher (63% vs. 28%, P < 0.05). Within this, 45% of patients in the mNGS group required the addition or escalation of antibiotics, compared to only 21% in the CMT group38. After receiving microbiological test results and adjusting for antibiotics, pulmonary infection improved in 27/43 patients (63%) in the mNGS group compared with 11/40 patients (28%) in the CMT group in the ensuing 7 days (P = 0.032)38.

The decision-making process regarding which organisms identified by mNGS are pathogenic and require treatment changes involves several key considerations. Clinical correlation with the patient’s symptoms, radiographic findings, and laboratory markers of infection is essential. Quantitative thresholds help distinguish between colonization and infection, minimizing overtreatment11. Host factors such as immunocompetence, presence of invasive devices, and recent antibiotic exposure are crucial in assessing infection risk39,40,41. Interdisciplinary consultations support comprehensive therapeutic decisions42. Future research should standardize mNGS data interpretation and validate findings through large-scale studies.

The impact on antibiotic stewardship and resistance

In our study, the implementation of a comprehensive treatment strategy based on mNGS facilitated the rapid identification of a wide range of pathogens. This approach contributed to targeted therapy and resulted in a significant increase in antibiotic adjustments within the mNGS group, including de-escalation, escalation, and the initiation of new antibiotics (Table 2). Adjustment of antibiotics based on accurate identification of pathogens may account for the improved outcomes, such as the increase in ventilator-free days within 28 days and the reduction in the duration of invasive ventilation. Another multicenter RCT on SCAP also showed that interpreting mNGS pathogen results through rigorous laboratory and informatic methods, involving expert panel discussions and adjudications, helps to distinguish between contaminants and true pathogens accurately. This leads to a higher rate of antibiotic de-escalation in the mNGS group compared to the CMT group, particularly in immunocompetent patients31. Such an approach is particularly significant in the context of antimicrobial resistance, as it allows de-escalation from broad-spectrum antibiotics to more targeted treatments, thereby reducing the likelihood of developing resistant strains.

Economic implications and health resource utilization

Multiple investigations have consistently identified postoperative complications as significant contributors to the elevated expenses associated with cardiac surgical procedures43. Among these, prolonged mechanical ventilation has been identified as the foremost factor contributing to the surge in complication-related expenditures, surpassing the economic impact of both cerebrovascular accidents and deep sternal wound infections44,45. Our study design focused on the impact of mNGS on clinical outcomes. Consequently, we did not include an economic analysis of the use of mNGS in the diagnosis and management of postoperative severe pneumonia in cardiac surgery patients. However, the potential impact of mNGS on healthcare economics warrants further discussion. The initial cost of mNGS is higher compared to CMT; however, the downstream financial benefits, such as reduced length of intensive care unit stay and lower readmission rates due to targeted treatment, could offset the upfront costs. Future research should include a comprehensive economic analysis to elucidate these potential savings.

Limitation

Our research also has certain limitations. Firstly, the retrospective design of our study introduces potential biases, especially in patient selection for mNGS testing. The higher initial testing costs associated with mNGS mean that it is more likely to be used in patients with more severe clinical presentations. This has resulted in baseline disparities between the patient groups undergoing mNGS and those receiving CMT, potentially confounding the comparison of outcomes between these groups. Second, our study was conducted at a single center and focused specifically on a relatively narrow patient population: individuals who developed severe pneumonia after cardiac surgery. This specificity, while valuable for targeted insights, results in a smaller sample size. The limited sample size poses challenges to the statistical robustness of our findings, necessitating a cautious interpretation of the data.

Conclusion

The study highlights the clinical utility of mNGS in diagnosing pathogens in adult patients with severe pneumonia following cardiac surgery. Our research suggests that mNGS could serve as a valuable complement to conventional diagnostic approaches, potentially improving diagnostic accuracy and leading to more precise and timely interventions, with significant potential to inform clinical decision-making and enhance patient outcomes. Further research should include a larger sample size, involving multi-center, prospective, and controlled studies, which will enhance our understanding of the impact of mNGS on the medium or long-term survival rate, economic implications and health resource utilization in this specific patient population.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- mNGS:

-

metagenomic next-generation sequencing

- BALF:

-

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- SICU:

-

surgical intensive care unit

- CMT:

-

conventional microbiological test

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- SIRS:

-

systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- HAP:

-

hospital-acquired pneumonia

- VAP:

-

ventilator-associated pneumonia

- ATS/IDSA:

-

American Thoracic Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CPB:

-

cardiopulmonary bypass

- RTs:

-

respiratory therapists

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- VIS:

-

vasoactive inotropic scores

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trial

- SCAP:

-

severe community-acquired pneumonia

- G test:

-

(1–3)-β-D-Glucan Test

- GM test:

-

Galactomannan antigen test

References

Badenes, R., Lozano, A. & Belda, F. J. Postoperative pulmonary dysfunction and mechanical ventilation in cardiac surgery. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2015, 420513 (2015). Epub 2015/02/24. doi: 10.1155/2015/420513. PubMed PMID: 25705516; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4332756.

Gaudriot, B. et al. Immune Dysfunction after Cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: Beneficial effects of maintaining mechanical ventilation. Shock (Augusta, Ga). ;44(3):228–233. Epub 2015/06/09. doi: (2015). https://doi.org/10.1097/shk.0000000000000416. PubMed PMID: 26052959.

Thompson, M. P. et al. Association between Postoperative Pneumonia and 90-Day episode payments and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing cardiac surgery. Circulation Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 11 (9), e004818. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.118.004818 (2018). Epub 2018/10/26.

Wang, D. S., Huang, X. F., Wang, H. F., Le, S. & Du, X. L. Clinical risk score for postoperative pneumonia following heart valve surgery. Chin. Med. J. 134 (20), 2447–2456. https://doi.org/10.1097/cm9.0000000000001715 (2021). Epub 2021/10/21.

Wang, D. et al. Pneumonia after Cardiovascular surgery: incidence, risk factors and interventions. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 911878. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.911878 (2022). Epub 2022/07/19.

Wang, D. et al. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia after cardiac surgery: a prediction model. J. Thorac. Disease. 13 (4), 2351–2362. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-3586 (2021). Epub 2021/05/21.

Ryz, S. et al. Identifying high-risk patients for severe pulmonary complications after Cardiosurgical Procedures as a Target Group for further Assessment of lung-protective strategies. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 38 (2), 445–450. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2023.11.030 (2024). Epub 2023/12/22.

Michalopoulos, A., Geroulanos, S., Rosmarakis, E. S. & Falagas, M. E. Frequency, characteristics, and predictors of microbiologically documented nosocomial infections after cardiac surgery. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic surgery. ;29(4):456–460. Epub 2006/02/17. doi: (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.12.035. PubMed PMID: 16481186.

Laffey, J. G., Boylan, J. F. & Cheng, D. C. The systemic inflammatory response to cardiac surgery: implications for the anesthesiologist. Anesthesiology. 97 (1), 215–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200207000-00030 (2002). Epub 2002/07/20.

Deurenberg, R. H. et al. Application of next generation sequencing in clinical microbiology and infection prevention. J. Biotechnol. 243, 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.12.022 (2017). Epub 2017/01/04.

Chen, J. et al. Metagenomic Assessment of the pathogenic risk of microorganisms in Sputum of postoperative patients with pulmonary infection. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. ;12:855839. Epub 2022/03/22. doi: (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.855839. PubMed PMID: 35310849; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8928749.

Jain, S. et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N. Engl. J. Med. 372 (9), 835–845. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1405870 (2015). Epub 2015/02/26.

Zhou, X., Su, L. X., Zhang, J. H., Liu, D. W. & Long, Y. Rules of anti-infection therapy for sepsis and septic shock. Chin. Med. J. 132 (5), 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1097/cm9.0000000000000101 (2019). Epub 2019/02/27.

Ferone, M., Gowen, A., Fanning, S. & Scannell, A. G. M. Microbial detection and identification methods: Bench top assays to omics approaches. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 19 (6), 3106–3129. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12618 (2020). Epub 2020/12/19.

Zhang, Y. et al. A cluster of cases of pneumocystis pneumonia identified by shotgun metagenomics approach. J. Infect. 78 (2), 158–169 (2019). PubMed PMID: 30149030.

Xiang, C. et al. First report on severe septic shock associated with human Parvovirus B19 infection after cardiac surgery. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1064760. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1064760 (2023). Epub 2023/04/24.

Gan, M. et al. Antimicrobial resistance prediction by clinical metagenomics in pediatric severe pneumonia patients. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 23 (1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-024-00690-7 (2024). Epub 2024/04/16.

Yang, J. et al. Microbial Community characterization and Molecular Resistance monitoring in geriatric intensive care units in China using mNGS. Infect. drug Resist. 16, 5121–5134. https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.s421702 (2023). Epub 2023/08/14.

Chen, T. et al. Detection of Pathogens and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia by Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing Approach. Infection and drug resistance. ;16:923 – 36. Epub 2023/02/24. doi: (2023). https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.s397755. PubMed PMID: 36814827; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9939671.

Kalil, A. C. et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clinical infectious diseases. Official Publication Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 63 (5), e61–e111. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw353 (2016). Epub 2016/07/16.

Erb, C. T. et al. Management of Adults with Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. ;13(12):2258-60. Epub 2016/12/08. doi: (2016). https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201608-641CME. PubMed PMID: 27925784.

Shi, Y. et al. Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults Journal of thoracic disease. 2019;11(6):2581 – 616. Epub 2019/08/03. doi: (2018). Edition https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.06.09. PubMed PMID: 31372297; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6626807.

Torres, A. et al. International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)/ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) of the European Respiratory Society (ERS), European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious diseases (ESCMID) and Asociación Latinoamericana Del Tórax (ALAT). Eur. Respir. J. 50 (3). https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00582-2017 (2017). Epub 2017/09/12.

Baughman, R. P., How, I., Do Bronchoalveolar & Lavage J. Bronchol. Interventional Pulmonol. ;10(4):309–314. (2003). PubMed PMID: 00128594-200310000-00017.

Pingleton, S. K. et al. Effect of location, pH, and temperature of instillate in bronchoalveolar lavage in normal volunteers. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 128 (6), 1035–1037. https://doi.org/10.1164/arrd.1983.128.6.1035 (1983). Epub 1983/12/01.

Meyer, K. C. et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cellular analysis in interstitial lung disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. ;185(9):1004-14. Epub 2012/05/03. doi: (2012). https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201202-0320ST. PubMed PMID: 22550210.

Haslam, P. L. & Baughman, R. P. Report of ERS Task Force: guidelines for measurement of acellular components and standardization of BAL. The European respiratory journal. ;14(2):245-8. Epub 1999/10/09. doi: (1999). https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14b01.x. PubMed PMID: 10515395.

Wang, X. et al. Healthcare associated infection management in 62 intensive care units for patients with congenital heart disease in China, a survey study. Int. J. Surg. (London England). https://doi.org/10.1097/js9.0000000000001138 (2024). Epub 2024/02/06.

Ren, J. et al. Multidrug-resistant bacterial infection in adult patients following cardiac surgery: clinical characteristics and risk factors. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23 (1), 472. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03488-1 (2023). Epub 2023/09/22.

Yang, T. et al. Clinical value of Metagenomics Next-Generation sequencing in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid for patients with severe hospital-acquired pneumonia: a nested case-control study. Infection and drug resistance. ;15:1505–1514. Epub 2022/04/13. doi: (2022). https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.s356662. PubMed PMID: 35411157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8994607.

Wu, X. et al. Effect of Metagenomic Next-Generation sequencing on clinical outcomes of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia in ICU: a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2024.07.144 (2024). PubMed PMID: 39067508Epub 2024/07/28.

Zhang, P. et al. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing for the clinical diagnosis and prognosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by severe pneumonia: a retrospective study. PeerJ. 8, e9623. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9623 (2020). Epub 2020/08/22.

Xie, Y. et al. Next generation sequencing for diagnosis of severe pneumonia: China, 2010–2018. J. Infect. 78 (2), 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2018.09.004 (2019). Epub 2018/09/22.

Innocenti, F. et al. Prognostic scores for early stratification of septic patients admitted to an emergency department-high dependency unit. Eur. J. Emerg. Medicine: Official J. Eur. Soc. Emerg. Med. 21 (4), 254–259. https://doi.org/10.1097/mej.0000000000000075 (2014). Epub 2013/08/24.

Jones, A. E., Trzeciak, S. & Kline, J. A. The sequential organ failure Assessment score for predicting outcome in patients with severe sepsis and evidence of hypoperfusion at the time of emergency department presentation. Crit. Care Med. 37 (5), 1649–1654. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819def97 (2009). Epub 2009/03/28.

Morkar, D. N., Dwivedi, M. & Patil, P. Comparative study of Sofa, Apache Ii, Saps Ii, as a predictor of mortality in patients of Sepsis admitted in medical ICU. J. Assoc. Phys. India. 70 (4), 11–12 (2022). Epub 2022/04/22. PubMed PMID: 35443485.

Zhang, X. et al. IL-15 induced bystander activation of CD8(+) T cells may mediate endothelium injury through NKG2D in Hantaan virus infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 1084841. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1084841 (2022). Epub 2023/01/03.

Zheng, Y. R., Lin, S. H., Chen, Y. K., Cao, H. & Chen, Q. Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the detection of pathogens in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of infants with severe pneumonia after congenital heart surgery. Front. Microbiol. 13, 954538. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.954538 (2022). Epub 2022/08/23.

Kumar, R. & Ison, M. G. Opportunistic Infections in Transplant Patients. Infectious disease clinics of North America. ;33(4):1143-57. Epub 2019/11/02. doi: (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2019.05.008. PubMed PMID: 31668195.

Cheng, G. S. et al. Immunocompromised host pneumonia: definitions and diagnostic criteria: an official American thoracic Society Workshop Report. Annals Am. Thorac. Soc. 20 (3), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202212-1019ST (2023). Epub 2023/03/02.

Rali, P., Veer, M., Gupta, N., Singh, A. C. & Bhanot, N. Opportunistic pulmonary infections in immunocompromised hosts. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 39 (2), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1097/cnq.0000000000000109 (2016). Epub 2016/02/27.

Patel, R. & Fang, F. C. Diagnostic Stewardship: Opportunity for a Laboratory-Infectious Diseases Partnership. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. ;67(5):799–801. Epub 2018/03/17. doi: (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy077. PubMed PMID: 29547995; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6093996.

Shander, A. et al. Clinical and economic burden of postoperative pulmonary complications: patient safety summit on definition, risk-reducing interventions, and preventive strategies. Crit. Care Med. 39 (9), 2163–2172. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821f0522 (2011). Epub 2011/05/17.

Mehaffey, J. H. et al. Cost of individual complications following coronary artery bypass grafting. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. ;155(3):875 – 82.e1. Epub 2017/12/19. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.08.144. PubMed PMID: 29248284. (2018).

Hadaya, J. et al. Impact of Pulmonary complications on outcomes and Resource Use after Elective Cardiac surgery. Ann. Surg. 278 (3), e661–e6. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000005750 (2023). Epub 2022/12/21.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their heartfelt gratitude to all the patients for their participation in this study. We also express our deep appreciation to the nursing and respiratory therapist teams of the Department of Intensive Care Unit at the Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital for their dedicated efforts in providing quality care.Furthermore, Chunlin Xiang would like to extend special thanks to Longjia Zeng for her patience, care, and unwavering support over the past few years.Finally, we are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which have significantly improved the quality of this paper.

Funding

This study was sponsored by the Sichuan Science and Technology Department (Grant no.2021YFS0380).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YPW, CLX and XXW designed the study. CLX, XXW, YZ, FZ, TRC, ZK, FCL, TYY, XYC, JJC and YW contributed to collection and collation the clinical data. CLX and HYX contributed to data curation and statistical analysis. CLX and XXW contributed to extract data from literature and manuscript writing. YPW, CLX, XXW, TLL, XMT, XBH, YW and CP contributed to manuscript revisions and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol used in this retrospective study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (No: 2024-30). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all data were anonymous before analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang, C., Wu, X., Li, T. et al. Effect of metagenomic next-generation sequencing on clinical outcomes in adults with severe pneumonia post-cardiac surgery: a single-center retrospective study. Sci Rep 14, 28907 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79843-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79843-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Unveiling the Future of Infective Endocarditis Diagnosis: The Transformative Role of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing in Culture-Negative Cases

Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health (2025)