Abstract

Developing contemporary antennas is a challenging endeavor that requires considerable engineering insight. The most laborious stage is to devise an antenna architecture that delivers the required functionalities, e.g., multiband operation. Iterative by nature (hands-on topology modifications, parametric studies, trial-and-error geometry selection), it typically takes many weeks and requires considerable engagement from a human expert. Consequently, only a few possible design options concerning the fundamental antenna geometry may be considered. Automated topology rendition and geometry parameter optimization are highly relevant, especially from the industrial perspective. Therein, reducing time-to-market and limiting the involvement of trained experts is critical. This research proposes an innovative procedure for unsupervised development of planar antennas. Our method leverages flexible antenna parameterization based on re-sizable elliptical patches. It permits the realization of a massive number of geometries of diverse shapes and complexities using a small number of decision variables. Computational intelligence methods are employed to conduct antenna evolution exclusively based on specifications and possible constraints (e.g., maximum size). Fine-tuning of the structure geometry is achieved through low-cost local search routines. Our methodology is demonstrated by designing several antennas featuring distinct characteristics (broadband, single-, dual- and triple-band). The obtained results, supported by experimental data, underscore the presented approach’s versatility and capability to render unconventional topologies at reasonably low computational expenses. As mentioned earlier, the design process is fully automated without human expert involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antennas are the fundamental elements of wireless communication systems (mobile phones, satellite communication, internet of things, etc1,2,3,4). , and other technologies such as radio-frequency identification, ambient energy harvesting, wearable/implantable electronics, medical imaging, to name just a few5,6,7,8. Conventional design approaches typically begin with existing antenna geometries available in previous generations of products, scientific publications, or structures developed using engineer’s insight. Subsequently, modifications are made to achieve the required functionality (e.g., circular polarization, multi-band operation). Having a rough design, parametric studies are employed9,10, or, recently, rigorous optimization methods such as bio-inspired techniques enhanced by the response-feature technology11 or multi-objective Bayesian optimization12 to adjust antenna dimensions, thereby boosting its performance concerning the figures of interest (impedance matching, gain, axial ratio). Most development stages, including optimization, use full-wave electromagnetic (EM) simulation models13 for evaluation dependability. The literature is replete with optimization strategies, specialized in local (e.g., sensitivity-based, derivative-free14,15,16,17,18), global19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 and multi-objective design30,31,32,33,34, and uncertainty quantification (UQ)35,36,37,38. Local methods incorporate various gradient-based algorithms14 also based on dedicated fast solvers15, procedures with sparse sensitivity updating schemes16,17, or stencil-based methodologies (i.e., various types of pattern search methods18). Global approaches often employ nature-inspired routines such as Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)19 or particle swarm optimization20, but also diverse machine learning methods22, and surrogate-assisted algorithms using both forward models (e.g., neural networks23, kriging24) and inverse ones21. On the other hand, multi-objective optimization is typically involving surrogate models (e.g., kriging)30, and incorporating mechanisms such as dimensionality reduction31 or objective aggregation32. UQ is heavily based on fast replacement models36 often specialized ones such as polynomial chaos expansion (PCE)37. Numerous accelerated techniques were developed as EM-driven design exerts significant computational costs35. Some worth mentioning methods include already mentioned surrogate-based routines, which can be based on data-driven metamodels (e.g., kriging36,38, PCE37,39, diverse types of artificial neural networks38,41,42,43,44,45,46, sometimes enhanced by other technique such as response features40. On the other hand, physics-based surrogates are also utilized, such as space mapping47,48 or a combination thereof with neural networks49. A popular method for accelerating EM-driven design is machine learning (ML)50,51, where the surrogate model (e.g., neural network52,53, deep neural network54) is used as a predictor yielding presumably high-quality candidate designs is iteratively updated using accumulated EM data55,56. Other popular techniques include the response feature technology57, exploiting a specific structure of the system’s outputs and weakly nonlinear dependence of the characteristic points on design variables58, often in connection with other methods (e.g., space mapping59 and multi-fidelity models60). Yet another approach is variable-resolution methods61, where the design process is expedited by incorporating faster but less accurate coarse-discretization models (or even equivalent circuit representations)62,63. To be reliably used in the design process, the lower-fidelity models are typically corrected using sparsely sampled high-fidelity data64 or utilized to carry out selected operations within the optimization framework65. A recent review of model- and ML-based antenna design methods can be found in66.

Performance enhancement and implementing additional functionality is often realized by adjusting basic antenna geometries (patches, monopoles, etc.), depending on the designer’s experience and preferences. Geometry optimization typically leads to designs that resemble the initial ones67,68. This and the long time required for experimentation with any given architecture are serious limiting factors regarding the number of alternative topologies that might be considered as potentially better options for a given application. Topology optimization (TO) is a different approach that allows for the adjustment of antenna geometry. One possibility is the spatial discretization of the area assigned to the antenna into pixels (square or rectangular shape), which may be filled with metal or left empty69,70,71,72,73. For example, in69, a radiator part of the antenna is discretized in the abovementioned manner, whereas in70, a discretized surface is employed to generate a high-performance metalens antenna. The work71 presents a subwavelength planar monopole antenna designed through the evolutionary generation of metalization patterns of the antenna’s radiator. Similar idea is exploited in73 to create a rectangular horn antenna. The pixel arrangement is typically determined using computational intelligence methods, primarily genetic algorithms (e.g.,74,75,80 binary particle swarm optimizer (BPSO)76, or quantum genetic algorithm77. In all these cases, due to the discretized structure of the antenna, the applied bio-inspired methods must be adopted to handle the combinatorial nature of the underlying optimization task. These techniques improve design flexibility at the expense of turning antenna development into a combinatorial problem of high complexity. In some approaches, only a specific antenna part (e.g., the radiator) is discretized69. Pixel antennas are a somehow different approach where the structure geometry is decided by allocating connections between pre-defined unit cells (typically squares). In some cases, the arrangement of the building block connections is realized using bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithms78,79. In other cases, multi-objective evolutionary algorithms are used82, or even gradient-based optimization incorporating adjoint sensitivities81,83. Yet another option is free-form TO, which enables considerably improved flexibility as the antenna geometry may take almost any shape84,85,86,87,88,89. For example, in84 an isolation structure in MIMO antenna has been developed through TO, whereas in85 topology optimization has been used to design a conical-beam antennas. The reference86 presents design of sub-wavelength antenna using TO. The design of antennas for energy harvesting can be found in87. Meanwhile, in88, TO was employed to develop both linear- and circularly polarized patch antenna structures. Finally89, presents the optimization of a multi-layer metasurface using a combination of TO and inverse neural network models. Free-form TO methods often employ fast custom-designed EM solvers to accelerate the development process15,90,91,92,93,94. This is necessary because the underlying optimization tasks are large-scale, so fast antenna evaluation is essential to make the TO-based methods practical. For example, the work90 employs a custom-designed finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) solver, similar to91 and94, whereas in92, a fast method of moments has been presented. A disadvantage of free-form TO is that the optimization uses gradient-based algorithms, making the outcome dependent on the initial architecture. Also, these techniques cannot be integrated with commercial simulation software packages, which is another limiting factor from the engineering perspective.

Considering the deficiencies of the above methods, a procedure allowing simultaneous determination of antenna geometry, and its optimum dimensions would be of considerable practical value. The crucial prerequisites include sufficient flexibility (in terms of an extensive range of architectural variations), the capability of implementing structures of diverse characteristics (broadband, multiband), and the possibility to integrate with commercial EM solvers. These features are essential for industrial applications from the perspective of time-to-market and the ability to devise unconventional antenna topologies potentially better suited for highly functional devices. This research attempts to deliver an innovative procedure that exhibits the mentioned properties and allows for automated specification-driven planar antenna development. The presented methodology capitalizes on the flexible parameterization of the antenna geometry involving elliptical patches and gaps of adjustable position and sizes. This allows for the implementation of a massive number of topologies of various shapes and complexity while using a limited set of decision variables. The design process is unsupervised and employs a combination of computational intelligence techniques to generate devices that fulfill the specifications concerning reflection responses and optional constraints (such as maximum size). Final geometry parameter tuning is done using local (gradient-based) algorithms. The specific dimensions and topology may be altered to boost the system’s performance at this stage. For demonstration, our technique is applied to design several antenna structures operating at different frequency bands and offering various functionalities (broadband, single-, dual- and triple-band). The results corroborate the versatility of our method and underscore its capability to produce unconventional topologies at practically acceptable computational expenses. The design process is utterly unsupervised, and no human-expert interaction is required.

This study delivers several technical contributions, which include (i) a novel and versatile antenna parameterization for generating immense variety of geometries with limited number of design variables, (ii) the development of automated design procedure combining bio-inspired and conventional (gradient-based) algorithms, (iii) demonstrating the capability of our method to conduct unsupervised antenna evolution and dimension tuning, (iv) demonstrating versatility of the framework through the design of structures featuring diverse functionalities obtained through purely specification-driven algorithm execution with no setup adjustments whatsoever, (v) ensuring that the presented approach can work in synergy with commercial EM simulation packages, thereby making it suitable for academic and industrial applications. Given the listed properties, the suggested algorithm can be considered an interesting and practical alternative to existing antenna design automation methodologies.

Specification-driven antenna design: the algorithm

This part of the study explains the details of the proposed automated development procedure. The considered type of antennas are planar structures implemented on single-layer dielectric substrates. Section 2.1 discusses antenna parameterization and demonstrates its flexibility. Section 2.2 and 2.3 outline the computational model and the algorithmic tools utilized to carry out the evolution and dimension adjustment of the antenna structure, respectively. The complete framework is summarized in Sect. 2.4.

Antenna parameterization

The fundamental component of the unsupervised design framework is antenna parameterization. Its essential features are simplicity (for easy handling), flexibility (to allow a multitude of distinct geometries, e.g., monopoles, dipoles, and patch antennas), and a limited set of design variables. The latter is essential to make the antenna evolution and optimization process numerically tractable and keep the computational costs practically acceptable. The design variables should be continuous to permit gradient-based tuning and discrete parameters to adjust the structure’s complexity as necessary. Furthermore, the parameterization must be straightforward to implement within commercial EM simulation environments (here, CST Microwave Studio is used as an underlying EM solver).

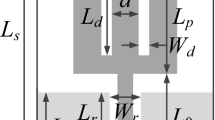

The components of the proposed parameterization that comply with the mentioned requirements have been listed in Table 1. In this study, the antenna is assumed to be rectangular, with an adjustable-length ground plane, discrete port, and several patches and gaps of adjustable location and size. The number NP of patches and NG of gaps determine the antenna complexity and can be treated as auxiliary variables during the antenna development. Another option is to decide about the complexity upfront and only employ continuous parameters, which will be employed when demonstrating the procedure in Sect. 3. For convenience, the position and sizes of all components relative to the substrate width W and length L. They are recalculated into absolute (physical) values for EM analysis.

The parameters listed in Table 1 are aggregated into a single vector that will be handled by the optimization procedures outlined in the next section. Given NP and NG, this takes the form of

Total number of design variables is n = 5 + 4(NP + NG).

Figure 1 shows assembling the antenna geometry by concatenating the elliptical patches and etching out the gaps for an exemplary setup. As indicated in Fig. 2, our parameterization enables a large variety of distinct topologies, even with a relatively small number of parameters (here, shown for NP = 5 and NG = 3). These shapes cannot be generated using traditional methods. Further, as the position and sizes of the building blocks are continuous variables, the antenna architecture may undergo global evolution and local tuning. For specific application areas, the antenna size may also be the subject of optimization or setup fixed to any specific substrate width and length values. This is a significant advantage over both pixel antennas and free-form topology optimization. Removing specific components from the computational model is realized by assigning them zero size.

Computational model

The computational representation of the designed device is prepared in CST Microwave Studio95. Table 1 lists all components of the proposed model. The pre-implemented number of patches and gaps is ten and six, respectively, which is more than sufficient for practical applications. As mentioned earlier, if the actual number of building blocks is set to smaller values, the redundant ones are assigned zero size, effectively being disabled.

To evaluate antenna characteristics, the design variable vector x is recalculated from relative to absolute parameters (cf. Table 1). The excessive patch metallization is trimmed to the substrate size. EM simulation is carried out in a batch mode with the antenna parameters controlled through a Visual Basic script. Upon simulation, the antenna responses are extracted from the output files exported by CST. The operating flow of the EM model evaluation scheme using the abovementioned concepts is presented in Fig. 3.

Optimization-driven antenna development

Here, we formulate the design task and discuss the architecture development of the antenna using computational intelligence methods and its final tuning through gradient-based optimization.

Design task

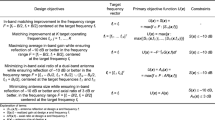

The design problem is posed for antenna impedance matching to make sure that the in-band |S11| ≤ − 10 dB over the band of interest F. For multi-band antennas, F = [f1 – B1/2, f1 + B1/2] ∪ [f2 – B2/2, f2 + B2/2] ∪ … ∪ [fK – BK/2, fK + BK/2], where fk and Bk are the center frequencies and the respective bandwidths (K being the number of bands). Consequently, our objective is to identify the parameter vector x*

with

In (2) X is the design space delimited by the bounds on geometry parameters. Recall that the parameterization proposed in Sect. 2.1 enables the vector x to represent both the antenna architecture and dimensions. Consequently, solving the problem (2) simultaneously adjusts the geometry and improves impedance matching performance. Additional requirements might also be imposed (e.g., miniaturization, gain, and/or radiation pattern requirement), which will be considered elsewhere.

It should be noted that in the considered case, a minimax objective function (3) is employed, which improves the impedance matching over the target frequency ranges. This is the formulation used in the result section (Sect. 3) of this work. Other formulations are possible, for example, targeting the improvement of the antenna gain, reducing its footprint (when using the substrate’s width and length are additional design variables), etc. In this paper, we focus on perhaps the most widely addressed objective which is impedance matching. Other design scenarios will be considered elsewhere.

Similarly, it is possible to make the parameterization even more flexible by incorporating additional parameters such as elliptical patches and gaps for the ground plane (rather than using a simple rectangular ground). This and other options will be considered in future work.

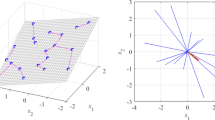

Antenna topology evolution

The first stage of antenna development is simultaneous global optimization of the architecture (spatial allocation of the patches and gaps) and the adjustment of building block dimensions. This is realized using a floating-point evolutionary algorithm 96,97 that incorporates elitism and adaptive mutation rate, outlined in Fig. 4. It should be noted that pm gradually decreases to zero later in the optimization process, improving the algorithm’s exploitation capability.

Local tuning

The final design process stage is local tuning aimed at improving the antenna performance regarding the cost function U (here, in-band impedance matching enhancement). At this point, antenna topology is essentially fixed. Only the sizes/locations of its building blocks vary slightly. This research’s underlying algorithm is the trust-region (TR) routine with numerical gradients98,99,102, outline in Fig. 5. The optimization process is handled by solving a sequence of sub-problems (cf. (8)), each producing the next optimum approximation. The search is performed in the vicinity of the current design using a Taylor expansion model of frequency characteristics. The task (8) is resolved by means of the Sequential Quadratic Approximation (SQP) algorithm100 built in Matlab Optimization Toolbox101.

Each iteration costs n + 1 EM simulations, n being the number of decision variables. However, as some building blocks have minor effects on antenna responses (e.g., due to their specific allocation), the respective parameters are excluded from further optimization if their impact (detected in the first iteration) is low. This way, the cost-effectiveness of the refinement process is greatly improved. For additional cost reduction, the global design stage uses coarse-discretization EM analysis. It is replaced by a higher-fidelity one in the second stage (final tuning).

Complete framework

The workflow of the suggested unsupervised design framework is illustrated in Fig. 6. As mentioned earlier, the antenna development process is specification-driven and requires no human expert input. The input parameters include parameters of the substrate (permittivity, thickness), substrate size (if treated as fixed), and target operating bands (cf. Section 2.3.1). The user may also decide the structure complexity by setting the number of active patches and gaps (NP and NG, respectively). During the two design stages, the antenna topology is first decided upon through evolutionary optimization (global stage), and final tuning (local stage).

It should be reiterated that the proposed methodology does not require setting up any initial values of the design parameters. The first stage of the design process is executed using a global search routine, here, the evolutionary algorithm. Its initial population is established randomly. This is a considerable advantage of the proposed method over many other techniques, e.g., free-form topology optimization, which relies on local search procedures (typically gradient-based). Because the design variables are relative (only recomputed to absolute antenna dimensions concerning the assumed substrate size), the parameter bounds are set very wide (from almost zero to 0.9), eliminating the problem of meticulous bound adjustment.

Demonstration examples

This part of the paper demonstrates the capability of our procedure regarding the unsupervised antenna design. It is used to develop several broadband and multi-band structures operating at diverse frequency ranges. Identical algorithm setup is employed for all examples to indicate that no control parameter tuning is necessary. Experimental data for selected designs support numerical results. The rest of the section is arranged as detailed below. Section 3.1 discusses the design prerequisites. Section 3.2 through 3.10 provide the results for specific test cases, whereas Sect. 3.11 summarizes the findings.

Experimental setup

The following arrangements have been made concerning the algorithm control parameters:

-

Substrate: FR-4 (εr = 4.4, h = 1.0 mm);

-

Model complexity: NP = 5, NG = 3;

-

Fixed substrate size: W = 30 mm, L = 20 mm;

-

Antenna topology development: control parameters as discussed in Sect. 2.3.2; computational budget 2000 EM simulations (100 iterations; population size N = 20);

-

Local tuning: control parameters as discussed in Sect. 2.3.3.

Recall that topology development is carried out using a low-fidelity EM model (~ 60,000 mesh cells, typical evaluation time 20 s), whereas local tuning employs the high-fidelity model (~ 200,000 mesh cells, typical evaluation time one minute).

An identical setup is applied to all test cases of Sect. 3.2 through 3.10 to demonstrate that there is no need to adjust the control parameters to specific performance requirements (here, target operating bands). The only exception is a UWB antenna designed in Sect. 3.4, where the antenna size has been reduced to W = 25 mm, and L = 15 mm to show the capability of our framework to design more compact structures as well.

Case I

The initial test case is a single-band antenna to operate in the 5.0 GHz to 6.0 GHz band. Figure 7 illustrates the final antenna geometry obtained with our technique and the reflection response. For an additional illustration, Fig. 8 shows several snapshots from the first design stage (topology evolution). Figure 9 shows the convergence plot for local tuning, a history of the minimax objective function, and a comparison of the initial (after a global search) and final |S11| characteristics. It can be noted that the global search stage already produces a good-quality antenna, whereas local tuning improves impedance matching by almost 1 dB within several iterations. Design specifications are fulfilled for the final structure. One should reiterate that the design process is entirely specification-driven, and no human expert is involved.

Case II

The second example is an ultra-wideband (UWB) structure working in the 3.1 GHz to 10.6 GHz band. The final geometry produced by the proposed framework and the corresponding reflection response are shown in Fig. 10. Figures 11 and 12 illustrate the topology evolution and the details of local tuning.

Case III

The third test scenario is also a UWB antenna. However, this antenna is implemented on a smaller substrate (15 mm × 20 mm in contrast to 20 mm × 30 mm for Case II). Nonetheless, design specifications have also been fulfilled in this case, as shown in Fig. 13. The snapshots of global search and local parameter adjustment can be found in Figs. 14 and 15, respectively.

Case IV

The next case involves a dual-band antenna operating from 2.4 GHz to 2.5 GHz and 5.2 GHz to 5.4 GHz. It can be noted that the design specifications are fulfilled with a good margin (cf. Fig. 16), and the global search already yields a solution of a good quality, requiring only a slight improvement through local tuning, see Figs. 17 and 18.

Case V

The following test scenario is a dual-band antenna operating from 2.4 GHz to 2.5 GHz and 7.0 GHz to 8.0 GHz. Also, in this case, the global search stage yields a good-quality design, so the local tuning only leads to minor dimension changes. The final geometry is shown in Fig. 19, whereas Figs. 20 and 21 illustrate antenna topology evolution and gradient-based tuning, accordingly.

Case VI

The next example is a broadband dual-band antenna operating from 3.1 GHz to 5.5 GHz and 7.5 GHz to 8.0 GHz. As indicated in Fig. 22, the final design fulfills the specifications, although it is a considerably more complex scenario due to broadband requirements in the lower band. Here, the global search results (Fig. 23) need to be adjusted (cf. Fig. 24) to meet the requirements eventually.

Case VII

The seventh test case is a dual-band antenna operating from 5.1 GHz to 5.9 GHz and 7.6 GHz to 7.9 GHz. The design produced by our technique almost fulfills the specifications (maximum in-band |S11| of around − 9.5 dB), cf. Figure 25. Figures 26 and 27 illustrate the global and local search stages. The latter improves the design by around 1 dB within a few iterations.

Case VIII

The eighth example involves a triple-band antenna operating in the ranges 2.4 GHz to 2.5, GHz, 5.2 GHz to 5.4 GHz, and 7.5 GHz to 8.0 GHz. As indicated in Figs. 28 and 29, and 30, for this case, the specifications are met in the first two operating bands and slightly violated in the upper band (7.5 GHz to 8.0 GHz). Notwithstanding, the antenna has been generated using the same algorithmic setup as for the previous test cases, and a triple-band operation was achieved using low-complexity architecture.

Case IX

The final example is again a triple-band antenna. The target operating frequency bands are 3.6 GHz to 3.7 GHz, 5.4 GHz to 5.5 GHz, and 9.8 GHz to 10.2 GHz.

As indicated in Figs. 31 and 32, and 33, for this case, the specifications are met in the first two operating bands and slightly violated in the upper band (7.5 GHz to 8.0 GHz). Notwithstanding, the antenna has been generated using the same algorithmic setup as for the previous test cases, and a triple-band operation was achieved using low-complexity architecture.

Surface current distributions for selected designs: (a) Case III, (b) Case IV, (c) Case VIII. The pictures underscore the utilization of the various parts of the antenna geometry at various frequencies. This corroborates the relevance of allocating the antenna’s building blocks during the topology evolution process.

Summary of findings

The results encapsulated in Sect. 3.2 through 3.10 conclusively demonstrate the efficacy and versatility of the proposed unsupervised antenna design strategy. Using a few elementary building blocks in conjunction with computational intelligence and rigorous optimization methods enables the automated design of a large variety of structures. These include single-band, dual-band, and triple-band devices, broadband antennas, and UWB radiators.

Figure 34 shows surface current distributions at various frequencies, scattered across the UWB band for Case III, and allocated at the centers of the respective operating bands for Cases IV and VIII. These pictures indicate the utilization of the various parts of the antenna geometry at different parts of the spectrum, demonstrating how particular building blocks have been allocated in the topology evolution process to ensure adequate antenna operation at the mentioned frequencies.

The design process of these diverse structures is purely specification-driven, and it does not require any adjustment of the algorithm setup. One of the critical components of the presented methodology is a combination of flexible parameterization, global search (for antenna architecture evolution), and local tuning for improving antenna performance, here, impedance matching. Furthermore, the antenna development process is realized using moderate expenses, amounting to 2000 low-fidelity EM analyses and between 100 and 300 high-fidelity EM simulations. This corresponds to the total CPU time of only around fifteen hours, which is very practical.

As elucidated earlier, the antenna performance is judged based on the value of the objective function, which, in this work, is a minimax function established for the reflection response. Consequently, the algorithm (its global and local parts) works towards improving U(x). If the value of the objective function falls below − 10 dB, the maximum in-band reflection level does not exceed the acceptance threshold of − 10 dB. Due to the stochastic nature of the evolutionary algorithm and ample parameter space (a few dozen decision variables), the procedure generally yields a different design each time it is executed. Consequently, there is no guarantee that any particular outcome is globally optimal. At this point, it should be emphasized that all antenna designs presented in the literature are always sub-optimal, not only due to the lack of appropriate optimization but—most importantly—due to considering a dramatically restricted number of topological options (often just one). The advantage of the presented approach is that it allows for considering a much more comprehensive range of antenna architectures while simultaneously optimizing the specific geometry dimensions.

Experimental validation

The designs produced in Sect. 3 have been prototyped and experimentally validated. For the sake of brevity, the experimental data for five selected designs is included here, specifically Cases I, III, IV, VI, and VIII. Figure 35 illustrates the measurement setup in the anechoic chamber for Case VI (the same setup was used for all antennas). Figures 36, 37, 38 and 39, and 40 show the photographs of antenna prototypes for the respective cases and the comparison between EM-evaluated and measured |S11| characteristics. As observed, these are well-aligned. Minor discrepancies stem from fabrication and assembly imperfections and the effects of the SMA connector not included in the EM model. Figures 41 and 42 show EM-evaluated and measured radiation patterns and realized gain for selected designs, specifically, Cases III, IV, and VIII.

Case I: (a) antenna prototype (cf. Fig. 10), (b) EM-simulated and measured |S11|.

Case III: (a) antenna prototype (cf. Fig. 13), (b) EM-simulated and measured |S11|.

Case IV: (a) antenna prototype (cf. Fig. 16), (b) EM-simulated and measured |S11|.

Case VI: (a) antenna prototype (cf. Fig. 22), (b) EM-simulated and measured |S11|.

Case VII: (a) antenna prototype (cf. Fig. 28), (b) EM-simulated and measured |S11|.

Conclusion

This research proposed an novel technique for automated development of planar antennas. The presented methodology combines a flexible parameterization consisting of a resizable ground plane, relocatable discrete port, and elliptical-shaped patches and gaps, with the antenna topology being a Boolean transformation of its elementary building blocks. The complexity of the device’s architecture is controlled by the number of active patches/gaps, the position and dimensions of which are treated as continuous design variables. During the evolution stage, antenna topology is adjusted using computational intelligence methods, and it is further tuned using a gradient-based algorithm oriented toward improving the impedance matching over the frequency ranges of interest. The entire development procedure is unsupervised and exclusively driven by specifications. No human expert involvement is required whatsoever.

Our approach was extensively demonstrated by designing several antennas of different functionalities (narrow-band, broadband, dual-band, triple-band), all generated using identical algorithmic setups. The obtained geometries are highly unconventional. Numerical results were accompanied by prototyping and measurements of selected structures. Our framework may be considered a step towards antenna design automation. It offers a viable alternative to methods based on pixel antennas (due to improved flexibility of the antenna geometry) and free-form topology optimization (due to the global search capabilities). It can be used to develop antennas for demanding applications such as wearable or virtual reality devices and whenever a specific (small) physical space is allocated for the antenna.

The presented methodology can, in principle, be applied to other antennas (e.g., patch or horn). However, this would require the establishment of an antenna-type-specific parameterization without changing the underlying search engines. The parameterization must incorporate building blocks typical for the antenna type to be designed. In the case of patch antennas, most of the existing parameterization might be reused. For horn antennas, the building blocks should be of the 3-D type (various types of apertures and horn sections parameterized using splines, etc.). This will be considered as a part of future work.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhao, W. & Wang, Y. A shared-branch eleven-band mobile antenna with a 0.5-mm clearance for metal-bezel mobile phones covering all the 4G LTE and 5G NR bands. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 72(4), 3748–3753 (2024).

Liao, H. P., Tsai, Y. T. & Chen, S. Y. A lightweight broadband circularly polarized stacked patch antenna formed by meshed aluminum disks for inter-satellite communication. IEEE Ant Wirel. Propag. Lett. 23(4), 1326–1330 (2024).

Kim, Y. B. & Lee, H. L. Wide-angle scanning flat panel array antenna for mmWave industrial-IoT coverage extension. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(7), 12874–12884 (2024).

So, K. K. & Wong, H. A monopolar metasurface dielectric resonator antenna with wide bandwidth for IoT applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(4), 7241–7248 (2024).

Erman, F. et al. A low-profile metal-backed dipole loaded with closely coupled arc-shaped open stubs for on-metal tag design with wide frequency tuning capability. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 72(4), 3772–3777 (2024).

Deng, F. & Luk, K. M. A broadband high-gain multibeam ambient millimeter-wave energy-harvesting system. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(3), 4888–4898 (2024).

Li, B., Wang, Y., Zhao, J. & Shi, J. Ultra-wideband antennas for wireless capsule endoscope system: a review. IEEE Open. J. Ant Propag. 5(2), 241–255 (2024).

Sharon Giftsy, A. L., Kommuri, U. K. & Dwivedi, R. P. Flexible and wearable antenna for biomedical application: progress and opportunity. IEEE Access. 12, 90016–90040 (2024).

Ullah, U., Al-Hasan, M., Koziel, S. & Ben Mabrouk, I. Circular polarization diversity implementation for correlation reduction in wideband low-cost multiple-input-multiple-output antenna. IEEE Access. 8(1), 95585–95593 (2020).

Wen, D., Hao, Y., Munoz, M. O., Wang, H. & Zhou, H. A compact and low-profile MIMO antenna using a miniature circular high-impedance surface for wearable applications. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 66(1), 96–104 (2018).

Koziel, S. & Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. Efficient simulation-based global antenna optimization using characteristic point method and nature-inspired metaheuristics. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 72(4), 3706–3717 (2024).

Zeng, Y., Qing, X. & Chia, M. Y. W. A wideband circularly polarized antenna with a nonuniform metasurface designed via multiobjective bayesian optimization. IEEE Ant Wirel. Propag. Lett. 23(6), 1739–1743 (2024).

Lei, S. et al. Power gain optimization method for wide-beam array antenna via convex optimization. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 67(3), 1620–1629 (2019).

Wang, J., Yang, X. S. & Wang, B. Z. Efficient gradient-based optimisation of pixel antenna with large-scale connections. IET Microwaves Ant Prop. 12(3), 385–389 (2018).

Lucchini, F., Torchio, R., Bettini, P. & Dughiero, F. TopIE: an integral equation tool for topology optimization in electromagnetics. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 72(1), 683–692 (2024).

Koziel, S. & Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. Variable-fidelity simulation models and sparse gradient updates for cost-efficient optimization of compact antenna input characteristics. Sensors. 19, 8 (2019).

Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. & Koziel, S. „Computationally-efficient design optimization of antennas by accelerated gradient search with sensitivity and design change monitoring. IET Microwaves Ant Prop. 14(2), 165–170 (2020).

Kolda, T. G., Lewis, R. M. & Torczon, V. Optimization by direct search: new perspectives on some classical and modern methods. SIAM Rev. 45, 385–482 (2003).

Li, X. & Luk, K. M. The grey wolf optimizer and its applications in electromagnetics. IEEE Trans. Ant Prop. 68(3), 2186–2197 (2020).

Luo, X., Yang, B. & Qian, H. J. Adaptive synthesis for resonator-coupled filters based on particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 67(2), 712–725 (2019).

Koziel, S. & Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. Global EM-driven optimization of multi-band antennas using knowledge-based inverse response-feature surrogates. Knowl. Based Syst. 227, 107189 (2021).

Dutta, K., Akinsolu, M. O., Kumar Mishra, P., Liu, B. & Guha, D. Application of machine learning-assisted global optimization for improvement in design and performance of open resonant cavity antenna. IEEE Open. J. Ant Propag. 5(3), 693–704 (2024).

Tan, J., Shao, Y., Zhang, J. & Zhang, J. Efficient antenna modeling and optimization using multifidelity stacked neural network. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 72(5), 4658–4663 (2024).

Braik, M., Hammouri, A., Atwan, J., Al-Betar, M. A. & Awadallah, M. A. „White Shark Optimizer: A novel bio-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 243, 108457 (2022).

Houssein, E. H. et al. „An efficient discrete rat swarm optimizer for global optimization and feature selection in chemoinformatics. Knowl.-Based Syst. 275, 110697 (2023).

Kumar, S. et al. „Chaotic marine predators algorithm for global optimization of real-world engineering problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 261, 110192 (2023).

Zhang, Q., Gao, H., Zhan, Z. H., Li, J. & Zhang, H. Growth optimizer: a powerful metaheuristic algorithm for solving continuous and discrete global optimization problems, Knowl.-Based Syst. 261, 110206 (2023).

Mostafa, R. R., Gaheen, M. A., ElAziz, M. A., Al-Betar, M. A. & Ewees, A. A. „An improved gorilla troops optimizer for global optimization problems and feature selection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 269, 110462 (2023).

Abdel-Salam, M., Alzahrani, A. I., Alblehai, F., Abu Zitar, R. & Abualigah, L. „An improved genghis khan optimizer based on enhanced solution quality strategy for global optimization and feature selection problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 112237 (2024).

Easum, J. A., Nagar, J., Werner, P. L. & Werner, D. H. Efficient multi-objective antenna optimization with tolerance analysis through the use of surrogate models. IEEE Trans. Ant Prop. 66(12), 6706–6715 (2018).

Koziel, S. & Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. Recent advances in accelerated multi-objective design of high-frequency structures using knowledge-based constrained modeling approach. Knowl.-Based Syst. 214, 106726 (2021).

Wolff, M. W. & Nanzer, J. A. Application of pseudoweights in antenna array optimization and design. IEEE Ant Wirel. Propag. Lett. 23(5), 1478–1482 (2024).

Li, J., Sun, G., Duan, L. & Wu, Q. Multi-objective optimization for UAV swarm-assisted IoT with virtual antenna arrays. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comp. 23(5), 4890–4907 (2024).

Mahmood, M., Koc, A., Morawski, R. & Le-Ngoc, T. Achieving capacity gains in practical full-duplex massive MIMO systems: a multi-objective optimization approach using hybrid beamforming. IEEE Open. J. Comm. Soc. 5, 2268–2286 (2024).

Xu, W., Wu, K., Li, P., Wang, C. & Qiu, Y. Grouping strategies of discrete elements for efficient power pattern tolerance analysis of antennas/radomes using Monte Carlo method. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 70(10), 9988–9993 (2022).

Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A., Koziel, S. & Al-Hasan, M. „Expedited yield optimization of narrow- and multi-band antennas using performance-driven surrogates. IEEE Access. 143104–143113 (2020).

Acikgoz, H. & Mittra, R. Stochastic polynomial chaos expansion analysis of a split-ring resonator at terahertz frequencies. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 66(4), 2131–2134 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Liu, B., Yu, Y. & Cheng, Q. S. A microwave filter yield optimization method based on off-line surrogate model-assisted evolutionary algorithm. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 70(6), 2925–2934 (2022).

Koziel, S. & Ogurtsov, S. Simulation-based Optimization of Antenna Arrays (World Scientific, 2019).

Feng, F. et al. Adaptive feature zero assisted surrogate-based EM optimization for microwave filter design. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Comp. Lett. 29(1), 2–4 (2019).

Zhang, Z., Chen, H. C. & Cheng, Q. S. Surrogate-assisted quasi-newton enhanced global optimization of antennas based on a heuristic hypersphere sampling. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 69(5), 2993–2998 (2021).

Cui, L., Zhang, Y., Zhang, R. & Liu, Q. H. „A modified efficient KNN method for antenna optimization and design. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 68, 6858–6866 (2020).

He, Y. et al. Hybrid method of artificial neural network and simulated annealing algorithm for optimizing wideband patch antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 72(1), 944–949 (2024).

Touhami, A., Collardey, S. & Sharaiha, A. A global optimization method for wideband and small supergain arrays design using Artificial neural network. IEEE Open. J. Ant Propag. 4, 1016–1028 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. An efficient method for antenna design based on a self-adaptive bayesian neural network-assisted global optimization technique optimization. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 70(12), 11375–11388 (2022).

Sonker, A., Nayak, A. K., Goel, T. & Patnaik, A. Multifunctional antenna design for wireless consumer electronic devices: a soft-computing approach. IEEE Can. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 46(2), 144–156 (2023).

Zhu, J., Bandler, J. W., Nikolova, N. K. & Koziel, S. Antenna optimization through space mapping. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 55(3), 651–658 (2007).

Cervantes-González, J. C. et al. Space mapping optimization of handset antennas considering EM effects of mobile phone components and human body. Int. J. RF Microw. CAE. 26(2), 121–128 (2016).

Zhang, W. et al. Advanced parallel space-mapping-based multiphysics optimization for high-power microwave filters. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 69(5), 2470–2484 (2021).

Wu, Q., Wang, H. & Hong, W. Multistage collaborative machine learning and its application to antenna modeling and optimization. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 68(5), 3397–3409 (2020).

Alzahed, A. M., Mikki, S. M. & Antar, Y. M. M. Nonlinear mutual coupling compensation operator design using a novel electromagnetic machine learning paradigm. IEEE Ant Wirel. Prop. Lett. 18(5), 861–865 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Hybrid ANN-GA optimization method for minimizing the coupling in MIMO antennas. AEU – Int. J. Electron. Comm. 175, 155068 (2024).

Gupta, A., Karahan, E. A., Bhat, C., Sengupta, K. & Khankhoje, U. K. Tandem neural network based design of multiband antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 71(8), 6308–6317 (2023).

Torun, H. M. & Swaminathan, M. High-dimensional global optimization method for high-frequency electronic design. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 67(6), 2128–2142 (2019).

Stanković, Z. Ž., Olćan, D. I., Dončov, N. S. & Kolundžija, B. M. Consensus deep neural networks for antenna design and optimization. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 70(7), 5015–5023 (2022).

Yasmeen, K., Mishra, K. V., Subramanyam, A. V. & Ram, S. S. Circularly polarized Fabry–Pérot cavity sensing antenna design using generative model. IEEE Sens. Lett. 7(2), 1–4, Art 3500304 (2023).

Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. & Koziel, S. Response Feature Technology for high-frequency Electronics. Optimization, Modeling, and Design Automation (Springer, 2023).

Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. & Koziel, S. „Generalized formulation of response features for reliable optimization of antenna input characteristics. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 70(5), 3733–3748 (2021).

Zhang, C., Feng, F., Gongal-Reddy, V., Zhang, Q. J. & Bandler, J. W. Cognition-driven formulation of space mapping for equal-ripple optimization of microwave filters. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 63(7), 2154–2165 (2015).

Koziel, S. & Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. Fast EM-driven nature-inspired optimization of antenna input characteristics using response features and variable-resolution simulation models. Sc. Rep. 14, 10081 (2024).

Jacobs, J. P. & Koziel, S. Two-stage framework for efficient gaussian process modeling of antenna input characteristics. IEEE Trans. Antennas Prop. 62(2), 706–713 (2014).

Li, J., Yang, A., Tian, C., Ye, L. & Chen, B. Multi-fidelity bayesian algorithm for antenna optimization. J. Syst. Eng. Electr. 33(6), 1119–1126 (2022).

Sendrea, R. E., Zekios, C. L. & Georgakopoulos, S. V. Multifidelity surrogate modeling based on analytical eigenfunction expansions. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 71(2), 1673–1683 (2023).

Koziel, S. & Leifsson, L. Simulation-driven Design by knowledge-based Response Correction Techniques (Springer, 2016).

Koziel, S. & Unnsteinsson, S. D. Expedited design closure of antennas by means of trust-region-based adaptive response scaling. IEEE Ant Wirel. Propag. Lett. 17(6), 1099–1103 (2018).

Sarker, N., Podder, P., Mondal, M. R. H., Shafin, S. S. & Kamruzzaman, J. Applications of machine learning and deep learning in antenna design, optimization, and selection: a review. IEEE Access. 11, 103890–103915 (2023).

Zhong, Y. et al. „A machine learning generative method for automating antenna design and optimization. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 68, 6858–6866 (2020).

Sharma, Y., Zhang, H. H. & Xin, H. Machine learning techniques for optimizing design of double T-shaped monopole antenna. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 68, 5658–5663 (2020).

Chen, Y. S. & Chiu, Y. H. Application of multiobjective topology optimization to miniature ultrawideband antennas with enhanced pulse preservation. IEEE Ant Wirel. Propag. Lett. 15, 842–845 (2016).

Liu, P., Chen, L. & Chen, Z. N. Prior-knowledge-guided deep-learning-enabled synthesis for broadband and large phase shift range metacells in metalens antenna. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 70(7), 5024–5034 (2022).

Ohira, M., Ban, H. & Ueba, M. Evolutionary generation of subwavelength planar element loaded Monopole antenna. IEEE Ant Wirel. Propag. Lett. 10, 1559–1562 (2011).

Arianos, S. et al. Application of evolutionary algorithms in the design of compact multi-band antennas, IEEE Int. Symp. Ant. Propag. 1–2 (2012).

Bird, T. S. Design of antennas through optimization of geometry, IEEE Int. Symp. Microwave Ant. Propag. EMC Techn. for Wireless Comm. 1 (2013).

Jiang, F., Chiu, C. Y., Shen, S., Cheng, Q. S. & Murch, R. Pixel antenna optimization using N-port characteristic mode analysis. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 68(5), 3336–3347 (2020).

Jing, L., Li, M. & Murch, R. Compact pattern reconfigurable pixel antenna with diagonal pixel connections. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 70(10), 8951–8961 (2022).

Ullah, M. A., Keshavarz, R., Abolhasan, M., Lipman, J. & Shariati, N. Multiservice compact pixelated stacked antenna with different pixel shapes for IoT applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 10(22), 19883–19897 (2023).

Bichara, R. M., Asadallah, F. A. B., Awad, M. & Costantine, J. Quantum genetic algorithm for the design of miniaturized and reconfigurable IoT antennas. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 71(5), 3894–3904 (2023).

Soltani, S., Lotfi, P. & Murch, R. D. Design and optimization of multiport pixel antennas. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 66(4), 2049–2054 (2018).

Lotfi, P., Soltani, S. & Murch, R. D. Printed endfire beam-steerable pixel antenna. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 65(8), 3913–3923 (2017).

Song, S. & Murch, R. D. An efficient approach for optimizing frequency reconfigurable pixel antennas using genetic algorithms. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 62(2), 609–620 (2014).

Jiang, F. et al. Pixel antenna optimization based on perturbation sensitivity analysis. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 70(1), 472–486 (2022).

Zheng, W. & Li, H. Designing antennas with quasi-isotropic radiation patterns using pixel structures. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 71(10), 7813–7823 (2023).

Qiao, T. et al. Pixel antenna optimization using the adjoint method and the method of moving asymptote. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 71(3), 2873–2878 (2023).

Zhu, S. H., Yang, X. S., Wang, J. & Wang, B. Z. Design of MIMO antenna isolation structure based on a hybrid topology optimization method. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 67(10), 6298–6307 (2019).

Wang, J., Yang, X. S., Ding, X. & Wang, B. Z. Topology optimization of conical-beam antennas exploiting rotational symmetry. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 66(5), 2254–2261 (2018).

Erentok, A. & Sigmund, O. Topology optimization of sub-wavelength antennas. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 59(1), 58–69 (2011).

Mori, T., Murakami, R., Sato, Y., Campelo, F. & Igarashi, H. Shape optimization of wideband antennas for microwave energy harvesters using FDTD. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag., 51(3), 1–4, Art 8000804 (2015).

Wang, J., Yang, X. S., Ding, X. & Wang, B. Z. Antenna radiation characteristics optimization by a hybrid topological method. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 65(6), 2843–2854 (2017).

Naseri, P. & Hum, S. V. A generative machine learning-based approach for inverse design of multilayer metasurfaces. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 69(9), 5725–5739 (2021).

Hassan, E., Noreland, D., Augustine, R., Wadbro, E. & Berggren, M. Topology optimization of planar antennas for wideband near-field coupling. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 63(9), 4208–4213 (2015).

Hassan, E., Wadbro, E. & Berggren, M. Topology optimization of metallic antennas. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 62(5), 2488–2500 (2014).

Tucek, J., Capek, M., Jelinek, L. & Sigmund, O. Density-based topology optimization in method of moments: Q-factor minimization. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 71(12), 9738–9751 (2023).

Wang, L. L., Yang, X. S. & Ma, C. J. An efficient gradient-based hybrid parameter-topology optimization for antenna design. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 71(12), 9477–9486 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. An optimized multiband antenna for UWB ad hoc networks based on topology optimization theory. IEEE Trans. Ant Propag. 72(5), 3896–3911 (2024).

Microwave Studio, C. S. T. ver. Dassault Systemes, France, 2023. (2023).

Michalewicz, Z. Genetic Algorithms + data Structures = Evolution Programs (Springer, 1996).

Blickle, T. & Thiele, L. A comparison of selection schemes used in evolutionary algorithms. Evol. Comp. 4(4), 361–394 (1996).

Conn, A. R., Gould, N. I. M. & Toint, P. L. Trust Region Methods (MPS-SIAM Series on Optimization, 2000).

Levy, H. & Lessman, F. Finite Difference Equations (Dover Publications Inc., 1992).

Nocedal, J. & Wright, S. J. Numerical Optimization 2nd edn (Springer, 2006).

Matlab MathWorks Inc. (2023).

Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. & Koziel, S. Numerically efficient algorithm for compact microwave device optimization with flexible sensitivity updating scheme. Int. J. RF Microw. CAE. 29, 7 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K., A.P.; methodology, S.K. and A.P.; data generation, S.K. and A.P.; investigation, S.K., A.P., and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, S.K., A.P., and S.S.; visualization, S.K. and A.P.; supervision, S.K.; project administration, S.K. and A.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koziel, S., Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. & Szczepanski, S. Versatile unsupervised design of antennas using flexible parameterization and computational intelligence methods. Sci Rep 14, 29753 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80319-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80319-z