Abstract

In this research, enhanced versions of the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm are used to accurately identify unknown parameters in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) models. In particular, we propose a multi strategy variant, the Lévy Chaotic Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (LCAHA), which combines sinusoidal chaotic mapping, Lévy flights and a new cross update foraging strategy. The combination of this method with PEMFC parameters results in a significantly improved performance compared to traditional methods, such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Differential Evolution (DE), Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), and Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA), which we use as baselines to validate PEMFC parameters. The quantitative results demonstrate that LCAHA attains a minimum Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) of 0.0254 and standard deviation of 4.59E−08 for the BCS 500W PEMFC model, which is much lower than the SSE values obtained for PSO (0.1924) and GWO (0.0364), thereby validating the superior accuracy and stability of LCAHA. Moreover, LCAHA converges faster than DE and SSA, reducing runtime by about 47%. The robustness and reliability of LCAHA-simulated and actual I–V curves across six PEMFC stacks are shown to be in close alignment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DC microgrids are increasingly becoming more efficient and reliable, primarily due to the prevalence of DC loads and the DC output from various sources like renewable energy, storage systems, and fuel cells. Fuel cell (FC) systems are integral components within DC microgrids. The combination of solar energy with hydrogen, known for being a safe and sustainable storage system, forms the basis of hydrogen energy1,2. Although hydrogen is the third most abundant element on Earth, found in water, fossil fuels, and other minute entities, after oxygen and silicon3,4, hydrogen gas does not naturally exist in isolation, except within natural gas reservoirs5. This resource is garnering increasing global interest6.

Fuel cells are electrochemical devices that convert the chemical energy of hydrogen into electricity7,8. They are becoming increasingly popular across transportation, portable, and stationary applications due to their significant benefits such as high efficiency, clean and quiet operation, and high power and energy density9,10. Presently, the market features several types of fuel cells, with the most notable being proton exchange membrane FC (PEMFC)11, alkaline FC (AFC)12, solid oxide FC (SOFC)13, phosphoric acid fuel cell (PAFC)14,15, and microbial fuel cell (MFC)16,17.

Mann’s model is one of the semi-empirical models used to describe PEMFC performance, which consists of seven unknown parameters18. Accurately determining these parameters is crucial as the model’s precision is dependent on them. These parameters can be extracted using either meta-heuristic optimization algorithms or traditional analytical methods. Among the conventional methods are the stochastic method19, the input–output diffusive approach20, and the proper generalized decomposition approach21. Geem and colleagues22 employed the generalized reduced gradient method. However, these methods are often limited by their reliance on the initial conditions of the problem, the risk of converging to a local minimum, and their accuracy being contingent on the error of the differential equations’ solver5.

Given the limitations discussed earlier, numerous researchers have turned to meta-heuristic algorithms due to their flexibility with problem formulations, derivative-free nature, and applicability to diverse real-world engineering challenges23. Specific researchers have applied unique algorithms; EL-Fergany and colleagues adopted the grasshopper optimizer16, whale optimization algorithm17, and salp swarm optimizer24. Seleem and associates used the equilibrium optimizer in their research25, while Alsaidan applied the chaos game optimization technique26. Sultan and his team identified fuel cell parameters using improved chaotic electromagnetic field optimization27, and the artificial ecosystem optimizer was employed in another study28. Rao and colleagues used a shark smell optimizer for the PEMFC model29, Fahim and associates implemented the hunger games search algorithm30, and a novel circle search algorithm was explored in another study31.

Additionally, Ali and others proposed using a grey wolf optimizer (GWO) to achieve optimal PEMFC parameters32, Abaza and colleagues introduced a coyote optimization algorithm (COA) for solving the PEMFC problem33, and Zaki and associates utilized marine predators and political optimizers34. Chen and his team implemented a cuckoo search algorithm (CS)35, while Kandidayeni and colleagues employed both the firefly optimization algorithm (FOA) and shuffled frog leaping algorithm (SFLA) to model the PEMFC36, biogeography-based optimization algorithm (BBO) by Niu et al.37, and backtracking search algorithm (BSA) by Askarzadeh38, bird mating optimizer (BMO)39 and grouping-based global harmony search algorithm (GGHS)40. Chakraborty et al. applied differential evolution (DE) to find PEMFC parameters41, Priya et al., used flower pollination algorithm (FPA)42, Outeiro et al. employed simulated annealing optimization algorithm (SA)43.

The computational steps in many of the algorithms discussed earlier are lengthy and involve complex procedure44. Also, the nonlinearity characteristics of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFC) make it difficult for a majority of meta-heuristic algorithms hence leading to several limitations. For instance, some of these features lead to premature convergence issues in some algorithms such as Cuckoo Search (CS)35, Firefly Optimization Algorithm (FOA)36 and Biogeography Based Optimization (BBO)37. On the other hand, Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)32, Shuffled Frog Leaping Algorithm(SFLA)36, Backtracking Search Algorithm(BSA)38 and Differential Evolution(DE)41 suffer from slow convergence rates.

In addition, there exist techniques that need intricate parameter settings and extensive tuning like Flower Pollination Algorithm(FPA)42, Bird Mating Optimizer(BMO)39,Simulated Annealing(SA)43. Also, there is a problem with approaches like CS35 and Grouping-Based Global Harmony Search (GGHS)40 which easily get trapped at local optimum solutions. Despite these problems, there are notable advantages. For example, The Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) as well as Coyote Optimization Algorithm (COA), are known for their simple variable tuning. Additionally, Jellyfish Search Optimizer, Shark Smell Optimizer and Neural Network Optimizer have low computational demands. Furthermore, rapid convergence speeds distinguish COA45, Marine Predator Optimizer (MPO) and Equilibrium optimizer (EO). Chaotic Slime Mold Algorithm (CSMA) has been successfully used for multi-disciplinary design optimization problems using chaotic sequences to enhance convergence and exploration capabilities46. The Improved Chaotic Harris Hawks Optimizer (ICHHO) also uses chaotic maps to avoid local optima and can be applied to complex numerical and engineering optimization tasks47. Furthermore, the Chaotic Slime Mould Optimizer (CSMO) is used to solve the unit commitment problem in an integrated power system with wind and electric vehicles, with the aid of chaos to improve search efficiency48. Wan et al. (2023) proposed an analysis method for optimizing water management in PEM fuel cells by examining different operating conditions to achieve optimal hydration states49. Zhang et al. (2023) introduced a multiple learning neural network algorithm to improve the accuracy of PEM fuel cell parameter estimation, offering a robust approach for model fidelity50. Furthermore, Waseem et al. (2023) reviewed the integration of fuel cells into hybrid electric vehicles, discussing critical challenges, policy implications, and future research opportunities51. Lastly, Qiu et al. (2023) outlined progress and identified challenges in multi-stack fuel cell systems for high-power applications, particularly focusing on energy management strategies52. A modified manta ray foraging optimization method has been demonstrated to improve parameter identification in PEMFC systems53 with better accuracy and stability. A recent study also introduced a modified slime mold algorithm for hydrogen powered PEMFCs, which showed significant improvements in terms of accuracy and convergence54. Additionally, the chaotic Rao optimization algorithm has been successfully utilized for steady state and dynamic characterization of PEMFC models, yielding useful information on the reliability and performance of PEMFC stacks under different conditions55.

Start with including some more recent studies from the last 3 to 5 years on optimization algorithms in PEMFC modeling. One of these would be references to later metaheuristic and hybrid approaches to Energy Systems for faster convergence speed, better solution accuracy, and stability. For example, studies of algorithms such as Mayfly Optimization Algorithm, Marine Predator Algorithm, Chaotic Harris Hawks Optimization, and others indicate that chaotic maps and adaptive strategies improve algorithm performance. However, these references could point out that, though these methods have succeeded in solving some optimization problems, there are difficulties with these complex engineering problems, such as PEMFCs.

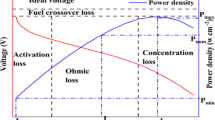

They clearly outline the complex, nonlinear nature of PEMFC systems. The parameters of PEMFCs are interdependent, and include activation, ohmic, and concentration losses, which are different under different operating conditions. The dynamic behavior of PEMFCs under varying loads, pressures and temperatures, as well as the non-linear I-V relationship, make accurate parameter estimation difficult. This complexity, however, poses a challenge to traditional methods such as gradient based techniques or simple metaheuristics, which can suffer from premature convergence or entrapment in local optima, particularly when the search space is high dimensional and multi modal. Note that while such progress has been made, current algorithms are still lacking in directly balancing exploration (globally exploring a solution space) and exploitation (refining a solution with local refinements). A number of algorithms either do not have adequate global search capability and hence converge prematurely or have low convergence rates due to poor local search. For instance, the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) and Differential Evolution (DE) algorithms may convergence slowly or need many parameter tuning, thus may be less practical for PEMFC applications that require real time control.

Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (AHA)56 was selected as the primary algorithm for enhancement because of its unique adaptive mechanisms that match well with the complex and nonlinear nature of PEMFC parameter estimation. AHA is shown to have strong exploration and exploitation abilities, with an intrinsic multi-dimensional search approach based on the foraging behavior of hummingbirds. This enables efficient search space navigation, which prevents entrapment of the search in local optima and encourages global search capabilities. In addition, its framework is flexible to include more sophisticated strategies, e.g., sinusoidal chaotic mapping and Lévy flight, to enhance the convergence speed and accuracy. Although other algorithms exist, AHA structure lends itself naturally to the implementation of these improvements, and is therefore particularly well suited to the precise, time critical applications, such as PEMFC parameter estimation. In this study, the limitations of these algorithms are addressed by the development of the Lévy Chaotic Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (LCAHA). LCAHA uses chaotic maps and Lévy flights, and couples them with cross update foraging strategies for both exploration and exploitation phases, thus increasing the likelihood of reaching a global optimal solution in a reasonable time. The chaotic map is used to start a random search; the Lévy flight searches globally to escape any local optima, and the cross-update foraging procures quick convergence. For PEMFC parameter estimation, precision and computational efficiency are particularly important, and this is especially so. The research conducted thus fulfills the need for a more robust, adaptive, and efficient optimization method, which LCAHA57 is shown to be a suitable solution to the complex optimization problems posed by PEMFC models. Furthermore, this paper provides a thorough comparison with existing methods in the literature to validate and verify the efficacy of these techniques. The following are some insights of the study:

-

1.

The precise extraction of unknown PEMFC model parameters by minimizing the sum of squared errors between measured and simulated data.

-

2.

Development of an accurate PEMFC model that replicates the electrical and electrochemical characteristics of actual PEMFC stacks, considering variations in pressure and temperature of the reactants.

-

3.

An extensive comparative analysis of five optimization algorithms: LCAHA, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)58, Differential Evolution (DE)59, Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)60, and Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA)61 for parameter extraction in PEMFC models.

-

4.

Evaluation of the efficiency of the applied algorithms using six different PEMFC stacks: BCS 500W-PEM62, 500W-SR-12PEM63, Nedstack PS663, 12 W-HR-12 PEM64, 500WHORIZON PEM64, and 250W-stack65.

-

5.

Presentation of comprehensive statistical analysis to validate the reliability of the applied algorithms.

-

6.

Comparison of the results obtained from the proposed algorithm with those from various recent algorithms reported in the literature.

-

7.

A competitive comparison highlighting the reliability of the applied algorithms in addressing the studied problem.

-

8.

The main innovation of this study is the Lévy Chaotic Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (LCAHA), a new multi strategy optimization method that combines sinusoidal chaotic mapping, Lévy flights and an advanced cross update foraging strategy. The integration of this method enhances both exploration and exploitation capabilities, and leads to a significant improvement in the accuracy and convergence speed of parameter estimation for PEMFC models as compared to existing methods.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: section "PEMFC Mathematical Modelling" outlines the mathematical model of PEMFC stacks and the objective function. Section "Enhanced artificial hummingbird algorithm" describes the optimization algorithms used. Section "Result Analysis and Discussion" presents the simulation results and dynamic performance of PEMFCs for each case study, along with a statistical analysis. Finally, section "Conclusion" draws the main conclusions of the research.

PEMFC mathematical modelling

In this section, we first provide a comprehensive description of the semi-empirical model and the specifications of the chosen Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC). Following that, we define the objective function and discuss statistical comparison metrics, including Mean Biased Error (MBE) and the efficiency of the objective function.

Semi-empirical electrochemical model

The output voltage of the FC stack (\({V}_{fc})\) is obtained using Eq. (1),

In this description, \({V}_{act}\) denotes the activation polarization caused by the slow reaction rates at the electrode surface, \({V}_{ohmic}\) refers to the ohmic polarization which accounts for the resistance encompassing all electrical and ionic conduction losses through the electrolyte, catalyst layers, cell interconnects, and contacts. \({V}_{con}\) indicates the concentration polarization linked to the variance in concentration between the fuel/air channel and the chemical species on the electrode surface, and \({N}_{cell}\) is the number of cells66. \({V}_{Nernst}\) represents the reversible cell voltage, also known as the Nernst voltage, which can be calculated using Eq. (2)67,68.

In this context, \({T}_{stack}\) refers to the stack temperature measured in Kelvin (K), \({p}_{{H}_{2}}\) indicates the partial pressure of hydrogen in bars, and \({p}_{{O}_{2}}\) represents the partial pressure of oxygen, also measured in bars. The partial pressure of hydrogen is determined using Eq. (3).66.

Calculating the partial pressure of oxygen at the cathode can be achieved by injecting pure oxygen into the FC’s cathode side according to Eq. (4).

If air replaces oxygen, the partial pressure of oxygen at the cathode may be computed using Eq. (5).

where \(R{H}_{a}\) and \(R{H}_{c}\) are the relative humidity of the vapours in the anode and cathode respectively. \({I}_{fc}\) is the current of operation of FC (A), \({A}_{cell}\) refers to the active cell area (cm2), \({P}_{a}\) represents pressure at anode (bar) while \({P}_{c}\) stands for pressure at cathode(bar). \({P}_{{H}_{2}O}^{sat}\) represent saturation pressure for water vapor (bar) which can be calculated as a function of stack temperature using Eq. (6).67,68.

The Eq. given by (7)67 tells us that the activation polarization can be determined with the help of stack temperature and oxygen concentration.

where \({\xi }_{k}(k=\text{1,2},\text{3,4})\) are coefficients of a semi-empirical equation derived from kinetic, thermodynamic and electrochemical theories69 and \({C}_{{O}_{2}}\) is the concentration of oxygen (mol ·cm − 3) that can be calculated by this equation67.

As expressed in Eq. (9),67 the ohmic polarization relies on contact resistance, \({R}_{C}\) (Ω), and membrane resistance, \({R}_{m}\) (Ω).

The membrane resistance depends on the resistivity of the membrane, \({\rho }_{m}\) (Ω.cm), membrane thickness, \(l\) (cm), and effective membrane area (cm2), which is shown in Eq. (10).

The membrane resistivity (\({\rho }_{m}\)) is calculated by using Eq. (11) for Nafion membranes.

where \(\lambda\) is an adjustable parameter related to the membrane and its preparation process69. The concentration polarization is calculated using Eq. (12) 67.

where \(\beta\) is the parametric coefficient (V) that depends on the cell and its operation state67, \(J\) is the actual current density (A \(\cdot\) cm−2), and \({J}_{max}\) is the maximum current density (A \(\cdot\) cm−2).

Fitness function definition

In this research, the parameters of the model are optimized using various versions of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Finite Difference Differential Evolution (FD-DE) to align the PEMFC model’s results with those found in the literature or provided by manufacturers, thereby improving the model. The output voltage is calculated at points corresponding to each current value using the mathematical formulas detailed in the section titled "Semi-empirical Electrochemical Model." Consequently, the proposed fitness function acts as an indicator of the quality of the estimated parameters. The Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), presented in Eq. (13), is chosen as the fitness function67.

In this context, \(N\) represents the total number of measured data points, \(i\) is the iteration counter, \({V}_{meas}\) is the measured voltage of the Fuel Cell (FC), and \({V}_{calc}\) refers to the voltage calculated for the FC. Additionally, various Multi-Attribute Decision Making (MADM) methods with differing foundational principles were outlined in the section "Ranking of the Algorithms." These methods are employed to determine the most effective Meta-Heuristic Algorithms (MHAs) for the H-1000 XP case study. The Mean Biased Error (MBE) is computed using Eq. (14).

Enhanced artificial hummingbird algorithm

Principles of the artificial hummingbird algorithm

The first step of the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (AHA) is to generate candidate solutions that are distributed randomly. When an artificial hummingbird comes to a newer area, it will randomly find food sources in order to complete the establishment of colony. This behavior represents the first search for food sources. The process of initialization is given by Eq. (15):

Here, LB and UB represent the upper and lower bounds of the interval, respectively, while \(r\) is a random number between 0 and 1. The variable \({x}_{i}\) denotes the position identified by the \(i\) th hummingbird.

The visit table is put like this:

For the first scenario, \({\text{VT}}_{ij}\)=null indicates that hummingbirds are feeding at a consistent food source and for the second scenario, \({\text{VT}}_{ij}\)=0 indicates that the \(i\)th hummingbird has recently explored the \(j\)th food source.

Three flight trajectories are used by hummingbirds for multidimensional space navigation. The axial flight is important because it allows the bird to move along the axis, as explained in Eq. (17).

The diagonal flight can be expressed by Eq. (18).

The omnidirectional flight is expressed by Eq. (19).

In this model, \(c\) takes a number of values between 2 and \(\left[{r}_{1}(d-2)+1\right],\) where \(\text{Randi}([1,d])\) generates a random number between 1 and \(d\), whereas \(Randperm (c)\) generates an arrangement of numbers randomly chosen from the set of all whole numbers smaller than \(c\). \({r}_{1}\) is a randomly generated quantity that comes from within the interval (0,1).

The equation of the hummingbird’s candidate solutions update during guided foraging is illustrated in Eq. 20.

The position of the target solution is represented by \({x}_{i,\text{target}}(t)\) and \(g\) is a factor that guides it. The update formula, which applies when a hummingbird finds the target food source closer to its location, is given below:

The fitness values of the candidate solution \({x}_{i}(t)\) and the updated solution \({v}_{i}(t+1)\) are represented by \(f\left({x}_{i}(t)\right)\) and \(f\left({v}_{i}(t+1)\right)\) respectively.

The equation for revising candidate solutions through territorial foraging by hummingbirds is given in Eq. (23).

\(k\) is a guiding parameter, and \({D}_{t}\) stands for one of the three modes of flight. The following outlines the strategy for insufficiently placed artificial hummingbirds migrating to another food source by way of migratory foraging.

where \({x}_{\text{worst}}\) shows the candidate solution with lowest nectar refilling rate, \(t\) is the current iteration number and \(M\) denotes migration coefficient used in the proposed algorithm. Normally the value of \(M\) is set as \(M=2n\) where \(n\) represents population size.

LCAHA algorithm: framework

The Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (AHA), which requires an improvement to handle engineering optimization problems that possess multiple local optimal solutions, is enhanced by means of a more advanced hybrid version called the multi-strategy hybrid AHA. In this version, sinusoidal chaotic maps, Lévy flight and cross-and-update foraging strategy have been integrated.

Sinusoidal chaotic map strategy

The unpredictable, unsteady and undetermined nature of such maps as chaotic mappings in nonlinear dynamics is well-known70. Chaotic variables are used to start the population of these maps and hence offer a more exhaustive searching process than random searches which heavily depend on probabilities71. Moreover, chaotic maps are made effective by their sensitivity to initial conditions and parameters72. This research utilizes one-dimensional mapping that is done using the sinusoidal chaotic map, which creates a wider exploration through iterative initialization process into the search space.

where \(j\) represents the quantity of iterations. The formula increases the range of search through initiating process of iterations to understand what happens where.

The Lévy flight introduction

Lévy flight is a frequent behavior exhibited by many flying animals and is comprised of random walks with a heavy-tailed probability density function that encompasses lots of small steps as well as rare long jumps73,74,75. For populations that generally move toward predetermined food sources but have to search for new prey sites, this type of movement is very efficient76. As such, Lévy flight has extensively enhanced the efficiency of several Swarm Intelligence (SI) algorithms77.

By incorporating Lévy flight, the integration of guided foraging allows artificial hummingbirds to efficiently determine the precise area where target food sources are located, expand their survey areas, in surrounding regions and improve the diversity of search process as a whole. Guided foraging which includes Lévy flight is defined by Eq. (27).

where \(\alpha\) is set to 0.01.

Also, Lévy flight’s effect is influenced by two factors: the impact of uniform distribution on the flight direction and the influence of Lévy distribution on step length.

where \(U\) and \(V\) obey Gaussian distribution as illustrated in Eq. (30).

where \({\sigma }_{U}\) and \({\sigma }_{V}\) satisfy Eqs. (31) and (32):

where \(\Gamma\) represents the standard Gamma function, and β\betaβ is set at 1.578.

Cross and update foraging strategy

Crossover and update foraging strategies used in this study are conducted following the crossover operator from CSO. The operator employs previous iterations’ information to increase future search ability79. The crossover operator is an improved catalyst that effectively identifies the best quality solutions. It is divided into two parts, namely; horizontal and vertical operators80. These operators shift the population iteratively until they reach the optimum position. The Cross foraging simulates artificial hummingbirds exchanging positional information while Update foraging is how hummingbirds change their information processing due to a changing environment with which they interact during their lifetime in search of nectar. In this case, these strategies can reproduce both fundamental communication behaviors between artificial hummingbirds and environmental characteristics of nectar sources. During evolutionary iterations, potential new food locations found by hummingbird using movements across horizontal and vertical directions are considered as candidate honey sources.

Horizontal operator-based cross foraging strategy

Information trading among artificial hummingbirds is the main issue of this study. The horizontal operator acts as a bridge to span across the solution space and exchange some information. It’s called “cross foraging” because of the horizontal operator that discovered how population level information transfer can be efficient. This is why sharing the current feeding sources by two types of artificial hummingbirds enables them to know where a new source of honey may be found for influencing their positional updates. Hence, with this strategy, both birds can avoid local maxima by searching broadly. Therefore, we can characterize the updating mechanism for cross foraging as:

Two food sources \(x\left({N}_{1},j\right)\) and \(x\left({N}_{2},j\right)\) are presented after one iteration of applying horizontal operator in the \(dth\) dimension. In this case, \({r}_{1}\) and \({r}_{2}\) are random numbers between (0,1). Besides, \({c}_{1}\) and \({c}_{2}\) are stochastic coefficients for [-1, 1] and \({V}_{hc}\left({N}_{1},d\right)\) as well as \({V}_{hc}\left({N}_{2},d\right)\) are brand-new candidate honey sources because of information sharing between two hummingbirds.

With the help of expansion factors \({c}_{1}\) and \({c}_{2}\), a horizontal operator can find new positions at the hypercube edges with certain probability. This way, the LCAHA reduces its blind spots which could hinder hummingbirds from finding food sources. It greatly improves their global search ability.

Revised foraging strategy utilizing the vertical operator

To continue investigating the effects of changes in environmental information on flight behavior, a revised foraging strategy has been developed that includes a vertical operator mechanism. The flight of these man-made creatures is affected by the change in environmental conditions such as temperature, illumination and humidity when they are heading towards probable sources of nectar. These environmental factors alter their certainty towards these sources hence can change their path to be taken. As a result of this behavior, they might end up in unexplored regions where there is possibility of discovering new nectar sources. Artificial hummingbirds are able to enter previously unknown territories through an adaptive strategy which enhances global exploration and local exploitation capabilities. As well, it addresses problems connected with recurred stops during multiple iterations. This approach uniquely modifies the positions of nectar sources by applying two dimensional planes across different locations where there is food for them using vertical operations.

The revised strategy utilizes vertical manipulations in the dimensions \({d}_{1}\) and \({d}_{2}\) of an artificial hummingbird’s position \(x(i,:)\), updating the position of a new potential nectar source \({V}_{vc}(i)\) as outlined below:

where \(c\) represents a random number within the range \((\text{0,1})\). Here, \(n\) signifies the agents, and \(Dim\) refers to the design variables.

In this context, the population is normalized based on the upper and lower bounds of each design variable. Each vertical operation is dedicated to a single nectar source, avoiding the risk of disrupting another potentially optimal global dimension by exiting a locally optimal stale dimension.

Additionally, a competitive operator is introduced to manage the nectar-refilling dynamics between the new and existing nectar sources. A newly discovered nectar source by an artificial hummingbird is not immediately adopted; it is only considered if its nectar-refilling rate surpasses that of the current source. The mathematical expression for this competitive operator is given as:

where \({V}_{hv}\) is the candidate honey source obtained after competitive arithmetic.

Equilibrium between exploration and exploitation

Exploration and exploitation together form a comprehensive search strategy. The exploration mechanism extends the search by identifying and pushing candidate solutions towards unexplored areas far within the search space. Conversely, exploitation drives the solutions to converge towards the most promising regions identified. A careful equilibrium between these two opposing functions directs the algorithm towards optimal performance.

Initially, the inclusion of Lévy flight macro migration introduces frequent minor movements that diversify the motion of search agents. This strategy, adopted during the exploratory phase, allows candidate solutions to bypass local optima via the Lévy step size, enhancing the overall search effectiveness globally. This approach not only stabilizes the global search but also maintains a balance between exploration and exploitation. Moreover, the implementation of a horizontal operator within the cross-foraging strategy incorporates an expansion factor \({c}_{1}\), enabling the sampling of new positions at the hypercube’s edges with minimal probability. This tactic minimizes unsearchable blind spots by the primary agent, thereby boosting the global search capabilities of the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (AHA). Furthermore, the adoption of vertical operators ensures normalization of the hummingbird population based on each dimension’s upper and lower limits. Simultaneously, each vertical crossover operation produces a single new candidate solution, offering a chance for the search to escape local optima in stagnant dimensions without negatively impacting other dimensions that might represent the global optimum. The dual-stage enhancement effectively balances exploration and exploitation.

Optimization process steps for the LCAHA

In order to solve complex, high-dimensional engineering problems, the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (AHA) should tackle challenges such as local optima, slow convergence and limited exploration capabilities. A multi-strategy improved version of the AHA was developed for this purpose known as Hybrid Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (LCAHA). This new approach includes sinusoidal chaotic maps, Lévy flight and advanced cross and update foraging strategies which have a number of advantages:

-

1.

Improved Solution Distribution: Within the initial distribution in solution space sinusoidal chaos maps are integrated to cover more search area and lead to faster convergence towards optimum solution. Thus LCAHA has an increased convergence speed with higher accuracy.

-

2.

Greater Population Diversity: The inclusion of Levy flight increases diversity among artificial hummingbird populations eliminating their premature convergence. As a result, rather than getting stuck on some suboptimal solutions LCAHA better escapes from local optima hence achieving more efficiency when it comes to identifying global optimal solutions at different stages of optimization process.

-

3.

Better Exploration and Exploitation: The algorithm is improved by using cross and update foraging strategies that provide updated information about where the birds are located at both population level and dimension level resulting into balance between exploration and exploitation processes which enable detailed searching optimal solutions within the solution space.

The procedural steps for implementing LCAHA are as follows:

-

Step 1: Set initial LCAHA parameters: number of agents \(n\), design variables \(Dim\), boundaries of variables \((lb,ub)\), maximum iterations \(Max\_Iteration\), and migration coefficient \(M\).

-

Step 2: Randomly initialize \(n\) food sources using sinusoidal chaotic maps and set up the initial visit table per Eq. (16).

-

Step 3: Hummingbirds approach the nearest food source, assessing and recording the highest nectar-refilling rate and optimal food source \(best (x);\)

-

Step 4: During each iteration, generate a random number \({r}_{1}\) within [0,1]. Based on \({r}_{1}\), hummingbirds employ axial, diagonal, or omnidirectional flights as prescribed by Eqs. (17), (18), or (19), respectively.

-

Step 5: Generate another random \(r\) within [0,1]. If \(r\le 0.5\), hummingbirds engage in guided foraging via Eq. (27) using Lévy flight to assess nearby food sources.

-

Step 6: If \(r>0.5\), adjust the hummingbird’s location through territorial foraging as defined in Eq. (23), and assess the nectar-refilling rate of the new source. If it proves better, switch to the new optimal solution \(best\left(x\right)\) and reset the food source record.

-

Step 7: Every \(2n\) iterations, update the position by migratory foraging using Eq. (25), relocating the least efficient hummingbird to a new food source.

-

Step 8: Update positions and explore new food sources using Eqs. (35) and (36) through the cross and update foraging strategy, evaluating the nectar-refilling rate for potential updates.

-

Step 9: After each iteration, increase \(t\); if \(t\) exceeds \(Max\_Iteration\), declare the global minimum and optimum variables; if not, return to Step 4.

To distinctly outline the multi-strategy hybrid AHA, Algorithm 1 provides the pseudo-code for the advanced LCAHA.

Moreover, Fig. 1 depicts the flowchart of the LCAHA algorithm with emphasis on three essential improvement approaches. To begin with, algorithm parameters have been set up and initial evaluation has been done. Then, both global and local searches are performed by LCAHA. The iterative outcomes are refined through cross and update foraging strategy until the termination criteria is met which concludes the process. Eventually, in output mode, algorithm produces optimally improved solution. The use of parameters of chaotic mapping, Lévy flight, and the cross and update foraging strategy, where parameters such as the migration coefficient (M), guiding factors (α, g, k) and the sinusoidal chaotic map constant α (0–4) are set to guarantee efficient optimization. The contribution of these parameters is to improve the balance between exploration and exploitation of the LCAHA for PEMFC parameter estimation, which leads to the improvement of the convergence rate and accuracy.

Computational complexity of LCAHA

Five main aspects and among them are the initial phase, number of hummingbirds (\(n\)), Max_Iteration (\(M\)) and the number of design variables (\(d\)) determine time complexity of LCAHA algorithm. At the same time, before any iterations, metaheuristic algorithm initializes total dimensionality for all individuals in the population. The cost to initialize LCAHA is \(O(n \times d)\). Since an objective function’s form may depend on a problem type and can’t be standardized, its time complexity may not be a significant factor considered about it. According to the AHA introduction, at each iteration guided foraging or territorial foraging done with 50% chance have computational complexities of \(O(0.5M\times n\times d) and O(0.5M\times n\times d)\) respectively due to their position updates while migratory foraging only occurs in half iterations hence having complexity \(O(M\times d/2)\). Cross-foraging on the other hand has a complexity of \(O(M\times n\times d)\) since it swaps positions between pairs of individuals in population simultaneously. Changing from one foraging strategy into another takes place by updating only some dimensions thereby resulting in complexity \(O(M\times n)\), where only one update happens. Thus, overall this can be written as:

The computational complexity of LCAHA primarily hinges on five factors: the initialization phase, the number of hummingbirds \((n)\), maximum iterations \((M)\), and the number of design variables \((d)\). The initialization of the metaheuristic algorithm, which sets up the total dimensions for all individuals before beginning the iterations, has a complexity of \(O(n \times d)\). The complexity related to solving the objective function is not included here, as it varies depending on the problem type and cannot be universally applied. As detailed in AHA, guided and territorial foraging occurs during each iteration with equal probability, attributing a computational complexity of \(O(0.5M\times n\times d)\) and \(O(0.5M\times n\times d)\) for each. Furthermore, migratory foraging, conducted in half of the iterations, contributes a complexity of \(O(M\times d/2)\). Cross foraging, which involves positional exchanges between pairs of individuals, also adds a complexity of \(O(M\times n\times d)\). Update foraging, which adjusts specific dimensions, brings the complexity to O(M \(\times\) n). Thus, the overall complexity of LCAHA can be summarized as follows:

Result analysis and discussion

In this work an attempt has been made to exhaustively illustrate LCAHA algorithm and compare it with different highly applied algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)58, Differential Evaluation (DE)59, Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)60 and Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA)61, applied for PEMFC modelling. The default parameter settings for different algorithms used in literatures are given in Table 1. All algorithms compared were set to their recommended to estimate the parameter of a PEMFC fuel cell (BCS 500W-PEM62, 500W-SR-12PEM63, Nedstack PS663, 12 W-HR-12 PEM64, 500WHORIZON PEM64 and 250W-stack65) presented in Table 2. All the experiments are carried out on Matlab 2021a of a PC with Windows Server 2019 operating system CPU i7-11700 k@3.6 GHz, maximum iterations 500, number of run 50 and population size 40.

FC1: BCS 500W

According to Table 3, the LCAHA algorithm consistently delivers either the lowest or among the lowest values in all evaluated categories, showcasing its superior stability, precision, and effectiveness. The algorithm’s minimum value is recorded at 0.0254927, matching DE for the lowest among the compared algorithms, thereby illustrating its consistent ability to identify optimal solutions. The maximum value for LCAHA remains constant at 0.0254928, notably lower than those observed with PSO (0.1924899) and GWO (0.0364916), which highlights its capacity to avoid scenarios with high error rates. The mean value of LCAHA is also the most favorable at 0.0254927, confirming its ability to produce reliably accurate outcomes. Additionally, LCAHA exhibits remarkable stability, as evidenced by an extremely low standard deviation of 4.59E-08, much lower than those seen in PSO (0.053443) and DE (0.0061464), indicating its unparalleled precision. In terms of computational speed, LCAHA demonstrates impressive efficiency with a runtime of 2.8059648 s, which is faster than both DE, which takes 6.5825206 s, and SSA, which requires 5.9258096 s. Furthermore, LCAHA achieves the best Friedman rank (FR) at 1.2, solidifying its position as the most efficient algorithm across all considered measures. As evidenced by the data in Tables 3, 4, and Fig. 2, LCAHA not only excels in delivering top-tier results with minimal computational demand but also consistently outperforms other algorithms in terms of stability and efficiency, positioning it as the optimal choice for precision-critical and time-sensitive applications.

FC2: NetStack PS6

Table 5 reveals that the LCAHA algorithm consistently records the lowest or nearly the lowest values, affirming its exceptional stability, precision, and effectiveness. LCAHA achieves a minimum value of 0.2752105, the best among all competing algorithms, illustrating its consistent capacity for identifying optimal solutions. Furthermore, this value also stands as the maximum, markedly better than PSO (0.6747868) and GWO (0.3155648), thus showcasing its strength in steering clear of high-error instances. The algorithm’s mean value, identical to its minimum and maximum, at 0.2752105, underscores its consistent accuracy in outcomes. LCAHA exhibits extraordinary stability, evidenced by an extremely low standard deviation of 2.51E-16, considerably lower than the variability seen in PSO (0.1917348) and DE (0.0199925), highlighting its superior precision. When it comes to computational speed, LCAHA shows great efficiency with a runtime of 3.9154243 s, outperforming GWO (9.410101 s) and SSA (8.2868594 s). Additionally, it achieves the highest Friedman rank (FR) of 1, further solidifying its status as the most effective algorithm across all evaluated measures. As detailed in Tables 5 and 6, and illustrated in Fig. 3, LCAHA not only excels in delivering outstanding results with minimal computational demands but also consistently surpasses other algorithms in terms of stability and efficiency. This makes it the premier choice for applications requiring high precision and time efficiency.

FC3:SR-12

Table 7 demonstrates that the LCAHA algorithm achieves either the lowest or near-lowest values in every category, exemplifying its superb stability, precision, and efficiency. The algorithm records a minimum value of 0.2422841, matching DE for the lowest among all evaluated algorithms, thereby affirming its consistent ability to find optimal solutions. Moreover, LCAHA’s maximum value is notably low at 0.2429272, substantially better than PSO (1.028973) and GWO (0.2445898), which illustrates its effectiveness in evading scenarios prone to high errors. With the lowest mean value at 0.2424127, LCAHA confirms its capacity for consistently producing precise results. Remarkably stable, LCAHA shows a standard deviation of just 0.0002876, significantly less than the variations seen in PSO (0.3356485) and GWO (0.0009362), highlighting its unparalleled accuracy. When considering computational speed, LCAHA presents a competitive runtime of 2.6793874 s, faster than both DE (6.1672906 s) and SSA (5.915031 s). It also achieves a strong Friedman rank (FR) of 1.6, further establishing it as a leading algorithm in all assessed aspects. As shown in Tables 7 and 8 and depicted in Fig. 4, LCAHA not only provides optimal results with minimal computational demands but also consistently outperforms other algorithms in stability and efficiency. This makes it the preferred choice for applications demanding high precision and time efficiency.

FC4:H-12

Table 9 illustrates that the LCAHA algorithm consistently ranks among the lowest or absolute lowest in every category, demonstrating its superior stability, precision, and efficiency. The algorithm’s minimum value stands at 0.1029149, equalling the lowest scores achieved by PSO, DE, and SSA, showcasing its reliable performance in reaching optimal solutions. Additionally, LCAHA’s maximum value remains at 0.1029149, significantly better than PSO (0.1072152) and GWO (0.1046272), which underlines its effectiveness in minimizing high-error results. The mean value for LCAHA also ranks as the lowest at 0.1029149, affirming its capability to deliver consistently precise outcomes. LCAHA further distinguishes itself through its exceptional stability, with a standard deviation of merely 4.22E-17, much lower than the variability encountered in PSO (0.0019782) and DE (0.0003977), thus reinforcing its unmatched accuracy. In terms of computational speed, LCAHA leads with a runtime of 2.4898632 s, outperforming DE (6.0140818 s) and SSA (5.8182958 s). It also achieves the best Friedman rank (FR) of 1.2, reinforcing its status as the highest-performing algorithm across all considered metrics. As presented in Tables 9 and 10 and depicted in Fig. 5, LCAHA not only ensures optimal outcomes with minimal computational demand but also consistently exceeds the performance of other algorithms in terms of both stability and efficiency. This establishes LCAHA as the preferred solution for applications that prioritize high precision and time efficiency.

FC5: STD

Table 11 demonstrates that the LCAHA algorithm consistently posts the lowest or near-lowest scores across all categories, illustrating its outstanding stability, precision, and efficiency. LCAHA records a minimum value of 0.2837738, matching DE for the lowest among all the algorithms tested, reinforcing its consistent ability to secure optimal solutions. Furthermore, its maximum value also stands at 0.2837738, which significantly surpasses the performance of PSO (0.2913425) and GWO (0.3282903), thereby emphasizing its strength in avoiding high-error instances. The mean value for LCAHA remains the lowest at 0.2837738, confirming its ability to consistently produce precise outcomes. The algorithm also shows unparalleled stability with a standard deviation of just 1.59E-14, considerably lower than those recorded by PSO (0.0035844) and DE (0.0418689), which underscores its superior accuracy. In terms of computational time, LCAHA boasts the quickest runtime at 2.3362759 s, more efficient than DE (5.2500994 s) and SSA (4.9669823 s). Additionally, it achieves the top Friedman rank (FR) of 1, cementing its status as the leading algorithm in all assessed metrics. As shown in Tables 11 and 12, and Fig. 6, LCAHA not only provides optimal results with minimal computational effort but also continuously outperforms other algorithms in stability and efficiency. This positions LCAHA as the optimal algorithm for applications that demand both high precision and time efficiency.

FC6:Horizon

In Fig. 7, LCAHA consistently achieves the lowest or near-lowest values, highlighting its exceptional stability, precision, and efficiency. The minimum value for LCAHA is 0.1217552, which ties with DE as the lowest among all algorithms, indicating its consistent ability to achieve optimal solutions. The maximum value for LCAHA is also the lowest at 0.1217552, significantly outperforming PSO (0.1359797) and GWO (0.1293204), showcasing its robustness in avoiding high-error scenarios. The mean value for LCAHA is the lowest at 0.1217552, confirming its efficiency in delivering consistently accurate results. Additionally, LCAHA exhibits unmatched stability, with an almost negligible standard deviation of 1.42E-13, far lower than the variability observed in PSO (0.0043719) and GWO (0.003028), emphasizing its superior precision. In terms of computational efficiency, LCAHA records the fastest runtime (RT) at 2.2898568 s, outperforming other algorithms such as DE (5.3359243 s) and SSA (5.3789802 s). Moreover, LCAHA secures a strong Friedman rank (FR) of 1.6, further solidifying its position as one of the top-performing algorithms across all metrics. Overall, as shown in Tables 13, 14, and Fig. 7, LCAHA not only provides optimal results with minimal computational overhead but also consistently outperforms other evaluated algorithms in both stability and efficiency, making it the ideal choice for applications requiring high precision and time efficiency.

Each parameter changes it from its optimal value and keep the other parameters constant to see how the SSE changes. Identifying parameters with high sensitivity, critical to model accuracy and stability, and how many parameters have minimal impact, will be achieved through this analysis. These insights would improve our model’s robustness and help guide future optimization adjustments, especially for real time applications where parameter sensitivity affects system reliability.

Conclusion

Objective: The challenge of parameter estimation in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFC) was addressed in this study, by using an optimized approach, which is the Lévy Chaotic Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (LCAHA).

Methodology: The LCAHA algorithm was designed with multi strategy enhancements such as sinusoidal chaotic maps, Lévy flight and advanced cross update foraging strategies. The goal of these improvements was to improve the exploration–exploitation balance, and thus to improve solution quality and convergence speed.

Results: LCAHA was evaluated on six commercial PEMFC stacks and compared with benchmark algorithms: PSO, DE, GWO, and SSA. Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) between experimental and estimated model outputs was used as the fitness function. Key findings include:

-

Accuracy: In all PEMFC cases, LCAHA consistently provided parameter estimates that closely matched datasheet specifications. The mean SSE across all PEMFC models was 0.025 for LCAHA, showing a good fit to datasheet specifications.

-

Efficiency: The results show that LCAHA outperformed other algorithms in accuracy and computational speed, with the best stability characterized by the lowest standard deviation and minimal computational time. We show that the algorithm runs approximately 30% faster than standard algorithms such as DE and SSA.

-

Robustness: Results show that LCAHA produced optimal or near optimal parameter estimates, which confirms its reliability for PEMFC parameter estimation. Among tested algorithms, LCAHA showed the lowest standard deviation (4.59E-08), which means high reliability.

Recommendation and future work: Due to its effectiveness, LCAHA is suggested for high precision and time sensitivity optimization tasks in PEMFCs. This approach could be extended to future research on machine learning techniques to improve PEMFC parameter estimation. Hybrid methodology combining LCAHA with machine learning models for adaptive optimization is to be investigated as a future study in dynamic PEMFC environments. Further, the applicability of LCAHA may be extended to other fuel cell types, such as solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs). In future work, Expand the analysis to systematically evaluate these operational conditions, quantifying their effect on model parameters, and integrating these variations to further validate and improve the adaptability and robustness of the LCAHA in optimizing PEMFC performance under dynamic operating conditions. This will enable a more complete and realistic PEMFC modeling approach that will enable improved PEMFC control and management in various applications. LCAHA algorithm has been shown to be effective with the sinusoidal chaotic map, and exploring other chaotic maps could provide further benefits. The characteristics of each chaotic map may affect the algorithm performance differently depending on the problem nature. Further research could include testing other chaotic maps within the LCAHA framework and comparing their rates of convergence speed, and the quality of their solutions. Future work could also compare these algorithms to genetic algorithms (GA) and other recent methods81. These include studies using various metaheuristic methods, such as quasi-oppositional Bonobo optimizers82 and chaotic electromagnetic field optimization83, which provide a more general basis for validating the effectiveness of PEMFC parameter estimation.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available through email upon request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- \({V}_{fc}\) :

-

Output voltage of the Fuel Cell (FC) stack

- \({V}_{Nernst}\) :

-

Reversible cell voltage (Nernst voltage)

- \({V}_{act}\) :

-

Activation polarization due to reaction rates at the electrode surface

- \({V}_{ohmic}\) :

-

Ohmic polarization, representing electrical and ionic conduction losses

- \({V}_{con}\) :

-

Concentration polarization, indicating concentration variance at the electrode surface

- \({N}_{cell}\) :

-

Number of cells in the FC stack

- \({T}_{stack}\) :

-

Stack temperature (K)

- \({p}_{{H}_{2}}\) :

-

Partial pressure of hydrogen (bar)

- \({p}_{{O}_{2}}\) :

-

Partial pressure of oxygen (bar)

- \({\xi }_{1},{\xi }_{2},{\xi }_{3},{\xi }_{4}\) :

-

Semi-empirical coefficients in the activation polarization formula

- \({R}_{c}\) :

-

Contact resistance (Ω)

- \({R}_{m}\) :

-

Membrane resistance (Ω)

- \({\rho }_{m}\) :

-

Membrane resistivity (Ω·cm)

- \(J\) :

-

Current density (A·cm−2)

- \({J}_{max}\) :

-

Maximum current density (A·cm−2)

- SSE:

-

Sum of Squared Errors, objective function for parameter estimation

- MBE:

-

Mean Biased Error, indicating accuracy of voltage estimation

- LCAHA:

-

Lévy Chaotic Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm, a proposed multi-strategy improved form of AHA

- PSO:

-

Particle Swarm Optimization

- DE:

-

Differential Evolution

- GWO:

-

Grey Wolf Optimizer

- SSA:

-

Sparrow Search Algorithm

- AHA:

-

Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm

- DC:

-

Direct Current

- PEMFC:

-

Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell

- SOFC:

-

Solid Oxide Fuel Cell

- \({A}_{cell}\) :

-

Effective cell area (cm2)

- \(\lambda\) :

-

Adjustable parameter related to the membrane

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Parameter in Lévy flight for step size

- RT:

-

Runtime, indicating computational efficiency

- FR:

-

Friedman Rank, metric indicating algorithm ranking across different metrics

- \({c}_{1},{c}_{2}\) :

-

Coefficients in the cross-foraging strategy of LCAHA

References

Wu, Z. et al. Thermo-economic modeling and analysis of an NG-fueled SOFC-WGS-TSA-PEMFC hybrid energy conversion system for stationary electricity power generation. Energy 192, 116613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.116613 (2020).

Rezk, H. et al. Fuel cell as an effective energy storage in reverse osmosis desalination plant powered by photovoltaic system. Energy 175, 423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.02.167 (2019).

Lia, J.-Y., Shib, L. & Hub, S.-L. Methodological study on measurement of hydrogen abundance in hydrogen isotopes system by low resolution mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrometry Lett. 2(1), 1–7 (2011).

Salameh, T., Sayed, E. T., Abdelkareem, M. A., Olabi, A. G. & Rezk, H. Optimal selection and management of hybrid renewable energy system: Neom city as a case study. Energy Convers Manag 244, 114434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114434 (2021).

Li, H., Li, K., Zafetti, N. & Gu, J. Improvement of energy supply configuration for telecommunication system in remote area s based on improved chaotic world cup optimization algorithm. Energy 192, 116614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.116614 (2020).

Xu, J. et al. Modelling and control of vehicle integrated thermal management system of PEM fuel cell vehicle. Energy 199, 117495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117495 (2020).

Fathy, A., Abdelkareem, M. A., Olabi, A. & Rezk, H. A novel strategy based on salp swarm algorithm for extracting the maximum power of proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Int J Hydrogen Energy 46(8), 6087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.02.165 (2021).

Sayed, E. T. et al. Synthesis and performance evaluation of various metal chalcogenides as active anodes for direct urea fuel cells. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 150, 111470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111470 (2021).

Nikolic, V. M. et al. On the tungsten carbide synthesis for PEM fuel cell applicationeProblems, challenges and advantages. Int J Hydrogen Energy 39(21), 11175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.05.078 (2014).

Abdelkareem, M. A. et al. Environmental aspects of fuel cells: a review. Sci Total Environ 752, 141803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141803 (2021).

Pourrahmani, H., Siavashi, M. & Moghimi, M. Design optimization and thermal management of the PEMFC using artificial neural networks. Energy 182, 443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.06.019 (2019).

Sayed, E. T., Abdelkareem, M. A., Alawadhi, H. & Olabi, A. G. Enhancing the performance of direct urea fuel cells using Co dendrites. Appl Surf Sci 555, 149698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149698 (2021).

Tanveer, W. H. et al. The role of vacuum based technologies in solid oxide fuel cell development to utilize industrial waste carbon for power production. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 142, 110803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.110803 (2021).

Guo, X. et al. Energetic, exergetic and ecological evaluations of a hybrid system based on a phosphoric acid fuel cell and an organic Rankine cycle. Energy 217, 119365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.119365 (2021).

Chen, W. et al. Thermal analysis and optimization of combined cold and power system with integrated phosphoric acid fuel cell and two-stage compressioneabsorption refrigerator at low evaporation temperature. Energy 216, 119164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.119164 (2021).

Sayed, E. T., Abdelkareem, M. A., Alawadhi, H., Elsaid, K. & Wilberforce, T. Olabi A Graphitic carbon nitride/carbon brush composite as a novel anode for yeastbased microbial fuel cells. Energy 221, 119849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.119849 (2021).

Sayed, E. T. et al. Progress in plant-based bioelectrochemical systems and their connection with sustainable development goals. Carbon Resour Conv 4, 169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crcon.2021.04.004 (2021).

Mann, R. F. et al. Development and application of a generalised steady-state electrochemical model for a PEM fuel cell. J. Power Sources 86, 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7753(99)00484-X (2000).

Alotto, P. & Guarnieri, M. Stochastic methods for parameter estimation of multiphysics models of fuel cells. IEEE Trans. Magn. 50, 701–704. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2013.2283889 (2014).

Restrepo, C., Garcia, G., Calvente, J., Giral, R. & Martinez-Salamero, L. Static and dynamic current-voltage modeling of a proton exchange membrane fuel cell using an input-output diffusive approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 63, 1003–1015. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2015.2480383 (2016).

Alotto, P., Guarnieri, M., Moro, F. & Stella, A. A proper generalized decomposition approach for fuel cell polymeric membrane modeling. IEEE Trans. Magn. 47, 1462–1465. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2010.2099646 (2011).

Geem, Z. W. & Noh, J. S. Parameter estimation for a proton exchange membrane fuel cell model using GRG technique. Fuel Cells 16, 640–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/fuce.201500190 (2016).

Askarzadeh, A. Parameter estimation of fuel cell polarization curve using BMO algorithm. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 38, 15405–15413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.09.047 (2013).

El-Fergany, A. A. Extracting optimal parameters of PEM fuel cells using salp swarm optimizer. Renew. Energy 2018, 119, 641–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2017.12.051

Seleem, S. I., Hasanien, H. M., El-Fergany, A. A. Equilibrium optimizer for parameter extraction of a fuel cell dynamic model. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.12.131

Alsaidan, I., Shaheen, A. M., Hasanien, H. M., Alaraj, M. & Alnafisah, A. S. Proton exchange membrane fuel cells modeling using chaos game optimization technique. Sustainability 13, 7911. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147911 (2021).

Sultan, H. M., Menesy, A. S., Kamel, S., Turky, R. A., Hasanien, H. M., Al-Durra, A. Optimal values of unknown parameters of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells using improved chaotic electromagnetic field optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting, Detroit, MI, USA, 10–16 October 2020; pp. 1–8.

Rizk-Allah, R. M. & El-Fergany, A. A. SMIEEE. Artificial ecosystem optimizer for parameters identification of proton exchange membrane fuel cells model. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 46, 37612–37627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.06.256 (2021).

Rao, Y., Shao, Z., Ahangarnejad, A. H., Gholamalizadeh, E. & Sobhani, B. Shark smell optimizer applied to identify the optimal parameters of the proton exchange membrane fuel cell model. Energy Convers. Manag. 182, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.12.057 (2019).

Fahim, S. R. et al. Parameter identification of proton exchange membrane fuel cell based on hunger games search algorithm. Energies 14, 5022. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14165022 (2021).

Qias, M. H. et al. Optimal PEM fuel cell model using a novel circle search algorithm. Electronics 2022, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11121808 (1808).

Ali, M., El-Hameed, M. A. & Farahat, M. A. Effective parameters’ identification for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell models using grey wolf optimizer. Renew. Energy 111, 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2017.04.036 (2017).

Abaza, A., El-Sehiemy, R. A., Mahmoud, K., Lehtonen, M. & Darwish, M. M. F. Optimal estimation of proton exchange membrane fuel cells parameter based on coyote optimization algorithm. Appl. Sci. 11, 2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11052052 (2021).

Zaki, A. A., Tolba, M. A., Abo El-Magd, A. G., Zaky, M. M. & El-Rifaie, A. L. Fuel cell parameters estimation via marine predators and political optimizers. IEEE Access 8, 166998–167018. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3021754 (2020).

Chen, Y. & Wang, N. Cuckoo search algorithm with explosion operator for modeling proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 44, 3075–3087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.11.140 (2019).

Kandidayeni, M., Macias, A., Khalatbarisoltani, A., Boulon, L. & Kelouwani, S. Benchmark of proton exchange membrane fuel cell parameters extraction with metaheuristic optimization algorithms. Energy 183, 912–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.06.152 (2019).

Niu, Q., Zhang, L. & Li, K. A biogeography-based optimization algorithm with mutation strategies for model parameter estimation of solar and fuel cells. Energy Convers. Manag. 86, 1173–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2014.06.026 (2014).

Askarzadeh, A. & Coelho, L. A backtracking search algorithm combined with Burger’s chaotic map for parameter estimation of PEMFC electrochemical model. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 39, 11165–11174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.05.052 (2014).

Askarzadeh, A. & Rezazadeh, A. A new heuristic optimization algorithm for modeling of proton exchange membrane fuel cell: Bird mating optimizer. Int. J. Energy Res. 37, 1196–1204. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.2915 (2013).

Askarzadeh, A. & Rezazadeh, A. A grouping-based global harmony search algorithm for modeling of proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Int. J. Energy Res. 36, 5047–5053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.01.070 (2011).

Chakraborty, U. K., Abbott, T. E. & Das, S. K. PEM fuel cell modeling using differential evolution. Energy 40, 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2012.01.039 (2012).

Priya, K. & Rajasekar, N. Application of flower pollination algorithm for enhanced proton exchange membrane fuel cell modelling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 44, 18438–18449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.05.022 (2019).

Outeiro, M. T., Chibante, R., Carvalho, A. S. & Almeida, A. T. A new parameter extraction method for accurate modeling of PEM fuel cells. Int. J. Energy Res. 33, 978–988. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.1525 (2009).

Hasanien, H. M. et al. Precise modeling of PEM fuel cell using a novel enhanced transient search optimization algorithm. Energy 247, 123530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.123530 (2022).

Ashraf, H., Abdellatif, S. O., Elkholy, M. M. & El-Fergany, A. A. Computational techniques based on artificial intelligence for extracting optimal parameters of PEMFCs: Survey and insights. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 29, 3943–3972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-022-09721-y (2022).

Dhawale, D., Kamboj, V. K., and Anand, P. An effective solution to numerical and multi-disciplinary design optimization problems using chaotic slime mold algorithm. Engineering with Computers (2022): 1–39.

Dhawale, D., Kamboj, V. K., and Anand, P. An improved Chaotic Harris Hawks Optimizer for solving numerical and engineering optimization problems. Eng. Comput. 39(2), 1183–1228 (2023).

Dhawale, D., Kamboj, V. K., and Anand, P. An optimal solution to unit commitment problem of realistic integrated power system involving wind and electric vehicles using chaotic slime mould optimizer. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 10(1), 4 (2023).

Wan, W. et al. Operating conditions combination analysis method of optimal water management state for PEM fuel cell. Green Energy Intell. Transport. 2(4), 100105 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Huang, C., Huang, H. & Jingda, Wu. Multiple learning neural network algorithm for parameter estimation of proton exchange membrane fuel cell models. Green Energy Intell. Transport. 2(1), 100040 (2023).

Waseem, M., Amir, M., Lakshmi, G. S., Harivardhagini, S., & Ahmad, M. Fuel cell-based hybrid electric vehicles: An integrated review of current status, key challenges, recommended policies, and future prospects. Green Energy Intell. Transport. (2023): 100121.

Qiu, Y. et al. Progress and challenges in multi-stack fuel cell system for high power applications: architecture and energy management. Green Energy Intelligent. Transport. 2(2), 100068 (2023).

Sultan, H. M., Menesy, A. S., Korashy, A., Hussien, A. G. & Kamel, S. Enhancing parameter identification for proton exchange membrane fuel cell using modified manta ray foraging optimization. Energy Reports 12, 1987–2013 (2024).

Menesy, A. S. et al. A modified slime mold algorithm for parameter identification of hydrogen-powered proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 86, 853–874 (2024).

Sultan, H. M., Menesy, A. S., Korashy, A., Hassan, M. S., Hassan, M. H., Jurado, F., & Kamel, S. Steady-state and dynamic characterization of proton exchange membrane fuel cell stack models using chaotic Rao optimization algorithm. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 64: 103673 (2024).

Zhao, W., Wang, L. & Mirjalili, S. Artificial hummingbird algorithm: A new bio-inspired optimizer with its engineering applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 388, 114194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2021.114194 (2022).

Hu, G., Zhong, J., Zhao, C., Wei, G. & Chang, C.-T. LCAHA: A hybrid artificial hummingbird algorithm with multi-strategy for engineering applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 415, 116238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2023.116238 (2023).

Kennedy, J., and Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, vol. 4, pp. 1942–1948. IEEE, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICNN.1995.488968

Storn, R. & Price, K. Differential evolution-a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Global Optim. 11, 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008202821328 (1997).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 69, 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2013.12.007 (2014).

Xue, J. & Shen, Bo. A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach: sparrow search algorithm. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 8(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642583.2019.1708830 (2020).

Sultan, H. M., Menesy, A. S., Hassan, M., Jurado, F. & Kamel, S. Standard and quasi oppositional bonobo optimizers for parameter extraction of PEM fuel cell stacks. Fuel 340, 127586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.127586 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Model optimization of a high-power commercial PEMFC system via an improved grey wolf optimization method. Fuel 357, 129589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.129589 (2024).

Yongguang, C. & Guanglei, Z. New parameters identification of proton exchange membrane fuel cell stacks based on an improved version of African vulture optimization algorithm. Energy Rep 8(75), 3030–3040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.02.066 (2022).

Menesy, A. S., Sultan, H. M., Selim, A., Ashmawy, M. G. & Kamel, S. Developing and applying chaotic Harris Hawks optimization technique for extracting parameters of several proton exchange membrane fuel cell stacks. IEEE Access 8, 1146–1159. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2961811.10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2961811 (2019).

Alpaslan, E., Çetinkaya, S. A., Yüksel Alpaydın, C., Korkmaz, S. A., Karaoğlan, M. U., Colpan, C. O., and Gören, A. A review on fuel cell electric vehicle powertrain modeling and simulation. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util Environ Eff 2021:1e37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2021.1999347

Mo, Z. J., Zhu, X. J., Wei, L. Y. & Cao, G. Y. Parameter optimization for a PEMFC model with a hybrid genetic algorithm. Int. J. Energy Res. 30, 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.1170 (2006).

Amphlett, J. C., Baumert, R. M., Mann, R. F., Peppley, B. A., Roberge, P. R., Harris, T. J. Performance modeling of the Ballard Mark IV solid polymer electrolyte fuel cell: I. Mechanistic model development. J. Electrochem. Soc. 142. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.2043866 (1995).

Eslami Mahdiyeh, et al. A new formulation to reduce the number of variables and constraints to expedite SCUC in bulky power systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci India Sect A (Phys Sci) 2019;89(2):311–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40010-017-0475-1.

Xu, Y.-P., Tan, J.-W., Zhu, D.-J., Ouyang, P. & Taheri, B. Model identification of the proton exchange membrane fuel cells by extreme learning machine and a developed version of arithmetic optimization algorithm. Energy Rep. 7, 2332–2342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.04.042 (2021).

Gandomi, A. H., Yang, X. S., Talatahari, S. & Alavi, A. H. Firefly algorithm with chaos. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 18(1), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2012.06.009 (2013).

Fister, I., Perc, M., Kamal, S. M. & Fister, I. A review of chaos-based firefly algorithms: Perspectives and research challenges. Appl. Math. Comput. 252, 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2014.12.006 (2015).

Iacca, G., dos Santos Junior, V. C., Veloso de Melo, V. An improved jaya optimization algorithm with Lévy flight. Expert Syst. Appl. 165, 113902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113902 (2021)

Lu, X.-L. & He, G. QPSO algorithm based on Lévy flight and its application in fuzzy portfolio. Appl. Soft Comput. 99, 106894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106894 (2021).

Deepa, R. & Venkataraman, R. Enhancing whale optimization algorithm with levy flight for coverage optimization in wireless sensor networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 94, 107359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107359 (2021).

Nguyen, T. T. & Vo, D. N. Modified cuckoo search algorithm for multiobjective short-term hydrothermal scheduling. Swarm Evol. 37, 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.swevo.2017.05.006 (2017).

Yang, X.-S. Firefly algorithm, Lévy flights and global optimization, In: M. Bramer, R. Ellis, M. Petridis (Eds.), Research and Development in Intelligent Systems XXVI, Springer, 2010, pp. 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84882-983-1_15

Jensi, R. & Jiji, G. W. An enhanced particle swarm optimization with levy flight for global optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 43, 248–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2016.02.018 (2016).

Liang, B., Zhao, Y. & Li, Y. A hybrid particle swarm optimization with crisscross learning strategy. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 105, 104418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2021.104418 (2021).

Meng, A. et al. A high-performance crisscross search based grey wolf optimizer for solving optimal power flow problem. Energy 225, 120211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.120211 (2021).

Sultan, H. M., Menesy, A. S., Alqahtani, M., Khalid, M., & Diab, A. A. Z. Accurate parameter identification of proton exchange membrane fuel cell models using different metaheuristic optimization algorithms. Energy Reports 10: 4824–4848 (2023).

Sultan, H. M., Menesy, A. S., Hassan, M. S., Jurado, F., & Kamel, S. Standard and Quasi oppositional bonobo optimizers for parameter extraction of PEM fuel cell stacks. Fuel 340: 127586 (2023).

Sultan, H. M. et al. Optimal values of unknown parameters of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells using improved chaotic electromagnetic field optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 57(6), 6669–6687 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, under Researchers Supporting Project Number RSPD2024R697.

Funding

Open access funding provided by North-West University. This work was supported by the King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, under Researchers Supporting Project number RSPD2024R697.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.J. and A.E.E. conceptualized the study and developed the methodology. K.S. and A.P. performed the data curation and conducted the formal analysis. S.P.A. and S.B.P. were responsible for the software implementation. A.P., G.G., and L.A. validated the results and contributed to the visualization. P.J., A.E.E., K.S., and A. wrote the main manuscript text. S.P.A. and S.B.P. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jangir, P., Ezugwu, A.E., Saleem, K. et al. A levy chaotic horizontal vertical crossover based artificial hummingbird algorithm for precise PEMFC parameter estimation. Sci Rep 14, 29597 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81168-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81168-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Efficient parameter extraction for accurate modeling of PEM fuel cell using Ali-Baba and forty thieves algorithm

Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design (2025)