Abstract

Owing to the simultaneous increase in the risk of thrombosis and bleeding in critically ill patients, point-of-care-available diagnostic tests to guide parenteral anticoagulation are warranted. We evaluated the detection of enoxaparin and argatroban, two commonly used parenteral anticoagulants, using the novel ClotPro viscoelastic coagulometer. For this experimental in vitro study at a tertiary care academic center, blood samples were drawn from twelve (six female, six male) healthy volunteers without intake of antithrombotic medication and no history of hemostatic disorders. Blood samples were spiked with enoxaparin (IU.ml− 1) and argatroban (µg.ml− 1) at increasing concentrations ranging from 0 to 1. The ClotPro Russell’s viper venom (RVV)-test and the ClotPro ecarin (ECA)-test clotting time were performed in parallel with conventional coagulation tests (anti-Xa activity, activated partial thromboplastin time, and diluted thrombin time). We observed a strong correlation between anti-Xa activity and the RVV-test clotting time (r = 0.88 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.8–0.92; p < 0.001)). Although clotting time cutoff values of 71 and 145 s provided high sensitivity and specificity for detecting anti-Xa activity of ≤ 0.1 and ≥0.6 IU.ml− 1, we found a poor performance at both high and low concentrations. The ECA-test clotting time revealed a very strong correlation with activated partial thromboplastin time (r = 0.96 (95% CI 0.93–0.97; p < 0.001)) and diluted thrombin time (r = 0.97 (95% CI 0.96–0.98; p < 0.001)). The clotting time cutoff values of 86 and 298–431 s provided high sensitivity and specificity for detecting diluted thrombin time values ≤ 0.1 and 0.5-1 µg.ml− 1. Our results suggest that the RVV test is an unreliable method for monitoring enoxaparin treatment, whereas the ECA-test might be an accurate point-of-care alternative for detecting argatroban concentration with potential advantages over standard coagulation tests in terms of point-of-care applicability and turnaround time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Critically ill patients are at an increased risk of venous thromboembolism, and routine pharmacological thromboprophylaxis forms a part of the standard of care in this patient cohort. In this context, current guidelines recommend the use of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWHs)1,2. In critically ill patients with confirmed or suspected heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, the parenteral direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban is the most commonly used alternative anticoagulant3.

In addition to an increased risk of thrombosis, critically ill patients typically exhibit a simultaneously increased risk of bleeding4,5. To provide reliable monitoring of the balance between thrombosis and bleeding, several laboratory tests are commonly performed. Anti-factor Xa (anti-Xa) activity is a widely used laboratory test to measure LMWH6. Target ranges between 0.6 and 1.0 IU.ml− 1 have been established for therapeutic anticoagulation7, whereas the utility of anti-Xa measurement in prophylactic anticoagulation remains a matter of debate8. For monitoring argatroban, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) represents the most used laboratory test. Target ranges are based on patients’ baseline values with a suggested 1.5- to 3-fold increase in aPTT9. However, particularly in critically ill patients, the validity of aPTT10 and its usefulness in argatroban monitoring11 has been questioned. Diluted thrombin time (dTT) is a promising alternative method that allows quantification of argatroban plasma concentration with suggested target ranges between 0.5 and 1.0 µg.ml− 1.9,12 However, anti-Xa, aPTT and dTT share the disadvantage of long turnaround times in potentially time-sensitive clinical situations.

Whole blood–based viscoelastic hemostatic assays are available at the point of care (POC) and have been shown to result in shorter turnaround times13. They are used in the context of goal-directed, individualized treatment algorithms for bleeding patients, whereas their potential value for the management of anticoagulation remains poorly investigated14. ClotPro, a novel viscoelastic coagulometer, offers commercially available assays for measuring the activity of Xa inhibitors (Russell’s viper venom test (RVV-test)) and thrombin inhibitors (ecarin-test (ECA-test)). Both tests employ the use of viper venoms that directly activate coagulation factors X and II, respectively, which makes them ideal candidates to detect the activity of anticoagulants targeting these factors, such as LMWH and argatroban.

We aimed to evaluate the feasibility of detecting the two widely used parenteral anticoagulants, enoxaparin and argatroban, at concentrations typically used in critically ill patients using the commercially available ClotPro assays RVV-test and ECA-test performed in whole blood. Additionally, we analyzed the correlations between (i) the RVV-test and plasma-based anti-Xa activity and (ii) the ECA-test and plasma-based dTT- and aPTT-values. We calculated cutoff values for detecting enoxaparin concentrations ≤ 0.1 IU.ml− 1 and 0.6-1 IU.ml− 1 as well as argatroban concentrations ≤ 0.1 µg.ml− 1 and 0.5-1 µg.ml− 1.

Methods

This in vitro pilot study of spiked whole blood samples from healthy volunteers was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK 1937/2022, 23/02/2023, Dr. Juergen Zezula) and was performed in accordance with the principles of good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted in the research laboratories of the Medical University of Vienna, Department of Anesthesia, Intensive Care and Pain Medicine, and the Department of Laboratory Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Study participants

Blood samples were drawn from 12 adult volunteers (six male and six female). Exclusion criteria were (i) known or identified (during the course of the study) hemostatic disorders, (ii) intake of anticoagulants and/or platelet aggregation therapy 14 days prior to enrolment, (iii) known renal or hepatic impairment, and (iv) current participation in another study. Blood was collected by venipuncture using Venflon™ Pro Safety 18 G in sodium citrate 3.2% blood collection tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria). No follow-up of volunteers was required.

Sample preparation

Citrated whole blood was spiked with either enoxaparin (Laboratorios Farmaceuticos Rovi SA, Spain) or argatroban (Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Austria) to target the following clinically relevant plasma concentrations:

Enoxaparin: 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0 anti-Xa IU.ml− 1.

Argatroban: 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0 µg.ml− 1.

Spiking solutions with decreasing concentrations of enoxaparin and argatroban were prepared, and 11 µL of each spiking solution was added to 2 ml of citrated whole blood. Spiked citrated whole-blood samples were incubated at 36 °C for 10 min to achieve stable conditions.

Standard laboratory tests and viscoelastic tests

Blood cell counts and standard laboratory coagulation tests were performed as the baseline measurements. Prothrombin time (PT) (Owren), aPTT, thrombin time, and fibrinogen level (Clauss method) were determined in plasma using an STA R Max 2 coagulometer (Diagnostica Stago SAS, Asnieres, France). Antithrombin activity was measured using a heparin cofactor AT assay based on thrombin inhibition (STA-STACHROM ATIII; Diagnostica Stago, Asnieres, France). Complete blood images, including red blood cells, leukocytes, platelet count, and haemoglobin were determined using a Sysmex XN-1500 cell counter (Sysmex, Vienna, Austria).

All viscoelastic measurements were performed in whole blood using the commercially available CE-certified viscoelastic coagulometer ClotPro (Enicor GmbH, Munich, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The principles of ClotPro measurements have been described previously15. Briefly, clotting is activated with different reagents depending on the respective test. Various parameters can be read out from the typical viscoelastic curve (Supplemental Fig. 1): clotting time (CT [s], defined as the time from the start of the test until an amplitude of 2 mm is reached), clot formation time (CFT [s], defined as the time from reaching 2 mm until an amplitude of 20 mm is measured), amplitude at 5, 10, 20, or 30 min after reaching a 2 mm amplitude (A5, A10, A20, A30 [mm]), and maximum clot firmness (MCF [mm]; maximum amplitude of the clot). EX-Test (coagulation activation by tissue factor) and IN-Test (coagulation activation by ellagic acid) were performed as viscoelastic baseline measurements from native whole blood samples. After spiking the whole blood samples, the RVV-test and ECA-test were performed in duplicate for each of the five enoxaparin-spiked blood samples (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1.0 IU.ml− 1) and argatroban-spiked blood samples (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1.0 µg.ml− 1), respectively.

The residues of the samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 2500 × g and 15 °C to obtain platelet-poor plasma, which was stored at -80 °C for subsequent measurement of anti-Xa activity (enoxaparin), aPTT, and dTT (argatroban). Anti-Xa activity was determined using STA-liquid anti-Xa calibrated for use with LMWH (Diagnostica Stago, Asnieres, France), and dTT measurements were performed using the Hemoclot DTI assay calibrated for use with argatroban (Hyphen BioMed, Neuville-sur-Oise, France). Measurements of aPTT were performed as previously described.

Statistical analysis

As this study was designed as a pilot study, a formal sample size calculation was not performed. The sample size was determined based on our experience from similar previously conducted experimental studies16,17 and previously published recommendations for sample size in pilot studies18.

We performed descriptive statistical analysis, presenting data as either mean with standard deviation or as median with 25th and 75th percentiles, and graphically using boxplots. To assess the association between continuous variables, we drew scatter plots and calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients. We considered values between 0.9 and 1.0 a very strong correlation, 0.7–0.89 a strong correlation, 0.5–0.69 a moderate correlation, 0.3–0.49 a weak correlation and < 0.3 no correlation. Cutoffs for the prediction of pre-specified anti-Xa activity and argatroban concentrations were determined by logistic regression. We considered the optimal cut-off values that maximized Youden’s index. We calculated the mean cutoffs, sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC) with standard deviations using bootstrapping with 1000 repetitions. R version 4.2.3, with the cutpointr package, was used for statistical analysis.

Results

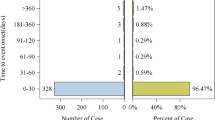

This study was conducted between February and April 2023. We recruited 12 volunteers who met predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The volunteer characteristics and baseline laboratory measurements are shown in Table 1.

Enoxaparin

In samples spiked with enoxaparin, we observed a dose-dependent increase in anti-Xa activity and dose-dependent prolongation of ClotPro RVV-test clotting times (CT) (Fig. 1A). The ClotPro RVV-test CT displayed high variance, particularly in samples with increased enoxaparin concentrations, whereas the anti-Xa activity showed a narrow distribution (Fig. 1A and B; Table 2). We found a strong correlation between anti-Xa activity and the ClotPro RVV-test CT (Fig. 1B; Table 2). In contrast, we observed a weak correlation between anti-Xa activity and the ClotPro RVV-test clot formation time (CFT). Furthermore, we observed no correlation between anti-Xa activity and ClotPro RVV-test amplitude after 5, 10, 20, or 30 min or between anti-Xa activity and ClotPro RVV-test maximum clot firmness (Table 2).

(A) ClotPro RVV-Clotting time and anti-factor Xa activity for samples spiked with enoxaparin. X-axis depicts the targeted enoxaparin concentration in plasma, whereas the right Y-axis depicts the measured anti-factor Xa activity. (B) Correlation between anti-factor Xa activity and ClotPro RVV-Clotting time (shaded area depicts 95% CI). (ClotPro was measured using whole blood, whereas anti-factor Xa activity was measured using plasma.)

A ClotPro RVV-test CT cutoff of 71 ± 3 s predicted anti-Xa activity ≤ 0.1 IU.ml− 1 with a sensitivity of 100 ± 1% and a specificity of 91 ± 4% (AUROC 0.95 ± 0.03), whereas a cutoff of 145 ± 16 s predicted an anti-Xa activity ≥ of 0.6 IU.ml− 1 with a sensitivity of 86 ± 9% and a specificity of 95 ± 7% (AUROC 0.94 ± 0.03) (Supplemental Fig. 2). Due to missing values that exceeded anti-Xa 1.0 IU.ml− 1, we were unable to calculate a respective ClotPro RVV-test CT cutoff.

Argatroban

In samples spiked with argatroban, we observed a dose-dependent prolongation of the dTT, aPTT, and ClotPro ECA-test CT (Figs. 2A and 3A).

(A) ClotPro ECA-Clotting time and diluted thrombin time for samples spiked with argatroban. X-axis depicts the targeted argatroban concentration in plasma, whereas the right Y-axis depicts the argatroban concentration measured by diluted thrombin time. (B) Correlation between diluted thrombin time and ClotPro ECA-Clotting time (shaded area depicts 95% CI). (ClotPro was measured using whole blood, whereas diluted thrombin time was measured using plasma.)

We observed a very strong correlation between the dTT values and ClotPro ECA-test CT, as well as between the aPTT values and ClotPro ECA-test CT (Figs. 2B and 3C; Table 3). All three monitoring methods displayed higher variances at increased argatroban concentrations, with aPTT showing the highest variance across all drug concentrations (Figs. 2 and 3; Table 3). In addition, we found a strong correlation between the dTT values and the ClotPro ECA-test CFT as well as between the aPTT values and the ClotPro ECA-test CFT (Table 3). In contrast, we observed no correlation between dTT values and ClotPro ECA-test amplitudes after 5, 10, 20, or 30 min, and no correlation between aPTT values and ClotPro ECA-test amplitudes after 5, 10, 20, or 30 min. Furthermore, we found no correlation between dTT values and the ClotPro ECA-test MCF or between aPTT and the ClotPro ECA-test MCF.

(A) ClotPro ECA-Clotting time and aPTT for samples spiked with argatroban. X-axis depicts the targeted argatroban concentration in plasma, whereas the right Y-axis depicts the aPTT (shaded area depicts 95% CI). (B) Correlation between aPTT and ClotPro ECA-Clotting time. (ClotPro was measured using whole blood, whereas aPTT was measured using plasma.)

A ClotPro ECA-test CT cutoff of 86 ± 1 s predicted dTT values ≤ 0.1 µg.ml− 1 with a sensitivity of 100 ± 0% and a specificity of 100 ± 0% (AUROC 1.0 ± 0), whereas a cutoff of 298 ± 9 s predicted dTT values ≥ 0.5 µg.ml− 1 with a sensitivity of 100 ± 0% and a specificity of 99 ± 2% (AUROC 1.0 ± 0), and 431 ± 12 s predicted dTT values ≤ 1 µg.ml− 1 with a sensitivity of 98 ± 1% and a specificity of 94 ± 4% (AUROC 0.98 ± 0.01) (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Discussion

In this prospective in vitro pilot study, we investigated the feasibility of detecting two commonly used parenteral anticoagulants (i) enoxaparin and (ii) argatroban, using the ClotPro RVV-test and ECA-test. We demonstrated that depending on their concentrations, prolonged clotting times occurred in the (i) ClotPro RVV-test and in the (ii) ClotPro ECA-test. Additionally, we found strong correlations between (i) anti-Xa activity and ClotPro RVV-test CT, and very strong correlations between (ii) dTT values and ClotPro ECA-test CT, as well as between aPTT values and ClotPro ECA-test CT. We found no correlation between clot firmness parameters (i.e. amplitude after 5, 10, 20, and 30 min as well as MCF) and anticoagulant concentrations or standard coagulation tests.

Owing to their POC applicability and the rapid availability of diagnostic results, viscoelastic hemostatic assays are recommended by clinical guidelines for the management of bleeding patients19,20. In contrast, the capability of viscoelastic devices to detect and guide anticoagulation remains poorly investigated. In the context of bleeding trauma patients, Oberladstätter et al. reported the feasibility of detecting clinically relevant plasma drug levels of direct oral anticoagulants using the ClotPro RVV-test and ECA-test15.

In line with their results, which showed strong correlations between plasma drug concentrations and ClotPro RVV-test CT for patients receiving direct oral factor Xa inhibitors, we found strong correlations between anti-Xa activity and ClotPro RVV-test CT after spiking blood samples with enoxaparin. The correlation between anti-Xa activity and ClotPro RVV-test CT has previously been investigated in patients receiving LMWH21,22. Bösch et al. found only a weak correlation between anti-Xa measurements and ClotPro RVV-test CT for critically ill patients who received LMWH. Similarly, Groene et al. observed moderate correlations between the two parameters in ten patients receiving LMWH.

Although we could identify ClotPro RVV-test CT cutoffs for detecting both anti-Xa activity ≤ 0.1 IU.ml− 1 and ≥ 0.6 IU.ml− 1, we found a wide variance of ClotPro RVV-test CT results at higher enoxaparin concentrations along with a rather poor detection of enoxaparin presence at low concentrations. The mean ClotPro RVV-test CT for both native blood samples and blood samples with a targeted concentration of 0.25 IU.ml− 1 LMWH were within the manufacturer’s reference range. These results are in line with Groene and colleagues, who found no difference in ClotPro RVV-test CT between patients receiving LMWH and a control group21. Strikingly, according to our results, an RVV-test CT of 100 s can occur at any enoxaparin concentration between 0.25 and 1.0 IU.ml− 1. Thus, we question the conclusions drawn by Groene et al. and argue that the results of our study, together with their findings, suggest the limited usefulness of the ClotPro-RVV test for monitoring LMWH.

When examining the correlation between the results obtained by the novel RVV-test and anti-Xa measurements, it is important to note the general lack of clarity regarding the relationship between anti-Xa activity and thromboembolic events (i.e., the clinical outcome of interest)8,23,24. Anti-Xa activity depicts plasma drug concentrations, and their association with the prevention of thromboembolic events, particularly in doses typically used for pharmacological thromboprophylaxis, remains pending8. For this reason, future studies employing the ClotPro RVV-test should include clinically relevant endpoints, such as thromboembolic events, instead of mere correlations with anti-Xa measurements.

The ClotPro ECA-test CT has been found to show strong correlations with plasma drug levels in patients taking the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran15. However, to the best of our knowledge, the capability of the ClotPro ECA-test to detect concentrations of the parenteral anticoagulant argatroban has not yet been investigated. In line with the results of Oberladstätter et al., we found very strong correlations between dTT results, aPTT results, and ClotPro ECA-test CT.

Despite being the most widely used laboratory method for guiding argatroban treatment, the accuracy of aPTT measurements has repeatedly been questioned, particularly in critically ill patients. Several factors, such as liver disease-related coagulopathy11,25, lupus inhibitors25 and elevated factor VIII26 have been shown to interfere with a reliable interpretation of aPTT results. Against this background, dTT has been advocated as an alternative, more accurate method for guiding argatroban treatment27,28. The results of our study suggest that the ClotPro ECA-test CT might be a valid alternative, with the advantage of rapid availability of diagnostic results at the POC. This is supported by the fact that, compared to the ClotPro RVV-test CT, the ClotPro ECA-test CT results exhibited a narrower range of variability for each concentration, allowing for clearer distinguishability between the different investigated argatroban concentrations. Furthermore, we could identify ClotPro ECA-test CT cutoff values that provided high sensitivity and specificity for detecting clinically relevant dTT ranges of ≤ 0.1 µg.ml− 1 and 0.5-1 µg.ml− 1.

Our study has several limitations. First, we presented the results of an in vitro pilot study with a small sample size. Although the study design does not permit direct translation of our findings into clinical practice, our results suggest the feasibility of guiding argatroban treatment using the ClotPro ECA-test CT, whereas our data do not support the use of the ClotPro RVV-test CT for the guidance of enoxaparin treatment. Second, although these questions might be of particular interest to critically ill patients, it should be stressed that we recruited healthy volunteers for this study, which hinders extrapolation of our results to real-life patient populations. Finally, we correlated the results of the novel diagnostic assays with monitoring methods that, although functionally depicting drug concentrations, have been poorly associated with relevant outcomes of interest, such as thromboembolic events.

Conclusions

We investigated the capability of two novel commercially available ClotPro assays to measure the activity of two parenteral anticoagulants, enoxaparin and argatroban, in vitro. Although we observed a strong correlation between the ClotPro RVV-test CT and anti-Xa activity, the wide variance in RVV-test CT measurements suggests that it is an unreliable method for monitoring enoxaparin treatment. In contrast, our findings indicate that ECA-test CT might be an accurate alternative to established laboratory tests for monitoring argatroban treatment, with advantages in terms of POC availability and turnaround time. Further diagnostic studies incorporating clinically relevant outcomes are warranted to confirm our in vitro results.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- aPTT:

-

activated partial thromboplastin time

- AUROC:

-

area under the receiver operating curve

- CFT:

-

clot formation time

- CT:

-

clotting time

- DTI:

-

direct thrombin inhibitor

- dTT:

-

diluted thrombin time

- ECA:

-

ecarin

- LMWH:

-

low molecular weight heparin

- MCF:

-

maximum clot firmness

- POC:

-

point of care

- PT:

-

prothrombin time

- RVV:

-

Russell’s viper venom

References

Fernando, S. M. et al. VTE Prophylaxis in critically ill adults: a systematic review and network Meta-analysis. Chest 161 (2), 418–428 (2022).

Duranteau, J., Taccone, F. S., Verhamme, P., Ageno, W. & ESA VTE Guidelines Task Force. European guidelines on perioperative venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: intensive care. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 35 (2), 142–146 (2018).

Bachler, M. et al. Thromboprophylaxis with argatroban in critically ill patients with sepsis: a review. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 33 (5), 239–256 (2022).

Neuenfeldt, F. S., Weigand, M. A. & Fischer, D. Coagulopathies in Intensive Care Medicine: Balancing Act between thrombosis and bleeding. J. Clin. Med. 10 (22), 5369 (2021).

Levi, M. & Opal, S. M. Coagulation abnormalities in critically ill patients. Crit. Care. 10 (4), 222 (2006).

Gehrie, E. & Laposata, M. Test of the month: the chromogenic antifactor xa assay. Am. J. Hematol. 87 (2), 194–196 (2012).

Wei, M. Y. & Ward, S. M. The Anti-factor Xa Range for low Molecular Weight Heparin Thromboprophylaxis. Hematol. Rep. 7 (4), 5844 (2015).

Gratz, J., Wiegele, M., Dibiasi, C. & Schaden, E. The challenge of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in ICU patients: anti-FXa activity does not constitute a simple solution. Intensive Care Med. 48 (8), 1116–1117 (2022).

Gruel, Y. et al. Diagnosis and management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 39 (2), 291–310 (2020).

van Roessel, S., Middeldorp, S., Cheung, Y. W., Zwinderman, A. H. & de Pont, A. C. J. M. Accuracy of aPTT monitoring in critically ill patients treated with unfractionated heparin. Neth. J. Med. 72 (6), 305–310 (2014).

Guy, S. et al. Laboratory methods for monitoring argatroban in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 44 (2), 399–406 (2022).

Marchetti, M. et al. Managing argatroban in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a retrospective analysis of 729 treatment days in 32 patients with confirmed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Brit J. Haem. 197 (6), 766–790 (2022).

Gratz, J. et al. Protocolised thromboelastometric-guided haemostatic management in patients with traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. Anaesthesia 74 (7), 883–890 (2019).

Gratz, J., Oberladstätter, D. & Schöchl, H. Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy and massive bleeding: current hemostatic concepts and treatment strategies. Hamostaseologie 41 (4), 307–315 (2021).

Oberladstätter, D. et al. A prospective observational study of the rapid detection of clinically-relevant plasma direct oral anticoagulant levels following acute traumatic injury. Anaesthesia 76 (3), 373–380 (2021).

Infanger, L. et al. Characterization of 2 different Prothrombin Complex concentrates by different hemostatic assays in an in vitro hemodilution model. Anesth. Analg. 135 (5), 1031–1040 (2022).

Gratz, J. et al. Comparison of fresh frozen plasma vs. coagulation factor concentrates for reconstitution of blood: an in vitro study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 37 (10), 879–888 (2020).

Julious, S. A. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharmaceut Statist. 4 (4), 287–291 (2005).

Rossaint, R. et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: sixth edition. Crit. Care. 27 (1), 80 (2023).

Kietaibl, S. et al. Management of severe peri-operative bleeding: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care: second update 2022. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 40 (4), 226–304 (2023).

Groene, P. et al. Viscoelastometry for detecting oral anticoagulants. Thromb. J. 19 (1), 18 (2021).

Bösch, J. et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin resistance and its viscoelastic Assessment in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Semin Thromb. Hemost. 48 (7), 850–857 (2022).

Dibiasi, C., Gratz, J., Wiegele, M., Baierl, A. & Schaden, E. Anti-factor xa activity is not Associated with venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients receiving enoxaparin for Thromboprophylaxis: a retrospective observational study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 888451 (2022).

Vahtera, A., Vaara, S., Pettilä, V. & Kuitunen, A. Plasma anti-FXa level as a surrogate marker of the adequacy of thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Thromb. Res. 139, 10–16 (2016).

Love, J. E., Ferrell, C. & Chandler, W. L. Monitoring direct thrombin inhibitors with a plasma diluted thrombin time. Thromb. Haemost. 98 (1), 234–242 (2007).

Kennedy, D. M. & Alaniz, C. Apparent argatroban resistance in a patient with elevated factor VIII levels. Ann. Pharmacother. 47 (7–8), e29 (2013).

Tardy-Poncet, B. et al. Argatroban in the management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a multicenter clinical trial. Crit. Care. 19, 396 (2015).

Hasan, R. A., Pak, J., Kirk, C. J., Friedland-Little, J. M. & Chandler, W. L. Monitoring direct thrombin inhibitors with calibrated diluted Thrombin Time vs activated partial Thromboplastin Time in Pediatric patients. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 159 (1), 60–68 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Anaesthesia, Intensive Care Medicine and Pain Medicine, Medical University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JG: Study design, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript draft and revision. SU: Data collection and analysis, manuscript draft and revision. FS: Data collection and manuscript revision. SK: Data collection and manuscript revision. CD: Analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. MW: Interpretation of data and manuscript revision. PQ: Data collection and manuscript revision. ES: Study design, interpretation of data and manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JG received honoraria, research funding, and travel reimbursement from Alexion, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, Instrumentation Laboratory, Johnson & Johnson, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Octapharma, Portola, and Takeda. SU received speaking fees from CSL Behring, Astra Zeneca, Arjo, Biomedica, Ekomed, NovoNordisk, and Roche. CD received speaking fees from CSL Behring, Astra Zeneca, Arjo, Biomedica, Ekomed, NovoNordisk, and Roche. ES received speaking fees from CSL Behring, Astra Zeneca, Arjo, Biomedica, Ekomed, NovoNordisk, Roche, B. Braun, and Bristol Myers Squibb. FS, SK, MW, and PQ declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK 1937/2022, 23/02/2023) and was performed in accordance with the principles of good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gratz, J., Ulbing, S., Schäfer, F. et al. Detection of enoxaparin and argatroban by use of the novel viscoelastic coagulometer ClotPro. Sci Rep 14, 29520 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81396-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81396-w