Abstract

Chloride-induced corrosion of steel rebars embedded in mortar was effectively controlled by blending of gallic acid in wet mixture. Mixing of optimized concentration of gallic acid (GA) inhibitor (0.125%) in mortars considerably increased the charge transfer resistance of embedded rebars (80.11 Ω cm2) in comparison to that noted for the control mortars (3.36 Ω cm2) after 37 cycles of wet/dry treatments. The corrosion inhibition efficiency after this cycle of exposure was of the order of 95%. The studied inhibitor also improved the workability (% flow of wet mix) from 25% for control to 43% at its optimum dosing. It is suggested that GA transforms into negatively charged gallate anions in an alkaline-pore solution of concrete and electrostatically attracted to the positively charged calcium ions, forming a complex with a partial positive charge. This complex interacts with the negatively charged maghemite film formed on rebar surface and forms a protective film of FeO− Ca++– GA anion, isolating it from the aggressive electrolyte. The experimental results showed that Ca++ ion of the concrete had a strong synergistic effect in boosting the inhibitive performance of the GA. The inhibition efficiency increased from 84.1% in the presence of GA only to 97.9% for the mixture of GA and calcium ions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete structures deteriorate because of many factors, but the uniform and localized corrosion of embedded steel rebars plays a crucial role in determining their longevity. A primary objective of civil engineers is to design and develop concrete structures with improved workability of fresh concrete, particularly in hot climatic regions, with higher strength and durability at minimal cost. Researchers have developed several novel ideas to address these challenges. Many methods and materials, including the use of high-alloy steel rebars, protective coatings on the surface of reinforcement bars, cathodic protection, addition of pozzolanic materials in concrete mixtures, application of superplasticizers, and use of corrosion inhibitors, have been employed to control corrosion and improve the workability and mechanical strength of cast structures. Many of these approaches not only make the process cumbersome, but also increase the cost of structures. With increasing concerns for the environment, soil, and water pollution, the development of environmentally friendly and sustainable multipurpose additives is another important aspect not only for civil engineers, but also for architects, municipal bodies, pollution experts, and government.

Literature search revealed that inhibitors application to control the corrosion of reinforcement bars exposed to concrete environments is widely reported1,2,3,4,5,6. Inorganic and organic corrosion inhibitors have been used in the construction industry to combat rebar corrosion in harsh concrete environments. Inorganic compound-based inhibitors, such as nitrites, phosphates, chromates and sulfites, suppress corrosion reactions by the passivation effect on metal surfaces or by scavenging oxygen, chloride, and other corrosive components present in concrete7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Several drawbacks are associated with this class of inhibitors, such as the need to blend their high concentrations (typically in the percentage range) in concrete to obtain the desired results and the leaching out over time, resulting in the acceleration of localized and uniform attacks, as well as polluting effects. Additionally, many of these inhibitors adversely affect the workability of freshly prepared concrete mixtures and the mechanical strength of cured concrete. The use of higher concentrations of inorganic inhibitors to achieve desired results is another disadvantage, as this can increase construction costs. As an alternative class of corrosion inhibitors, organic inhibitors contain synthetic or naturally occurring chemical compounds with N, O, P, and S atoms in their molecules. The free lone pair of π electrons available in the outermost orbits of the electronic structures of these elements function as active centers for their adsorption, either in molecular or ionic forms, on metallic surfaces16. Because corroding metal-electrolyte interfaces acquire negative or positive charges, inhibitors interact with such interfaces through their active centers to form an adsorption layer and change the structure of the double electrical layer. These layers isolate metal surfaces from aggressive components of corrosive environments and protect them from corrosion17. Organic-compound-based corrosion inhibitors offer several advantages. The most attractive factor is their effectiveness at exceptionally low concentrations (usually in the parts per million (ppm) range) for the effective protection of reinforcement bars under adverse conditions. Consequently, this factor enables economical construction and has negligible long-term effects on the properties of the cast structures. Economic considerations, pollution concern and sustainability issues have resulted in exploring the possibilities of use of organic compounds derived from plants to control the corrosion of metals in different environments. The seeds, fruits, and leaves of plants contain gallic acid (GA), tannic acid, alkaloids, steroids, sugars, and flavonoids, which act as corrosion inhibitors for metals and alloys in contact with different corrosive electrolytes18,19,20,21,22,23,24. These constituents impart corrosion protection to metallic surfaces owing to the combined effects of different active compounds present in various parts of plants. The content of the active components in plants that are responsible for corrosion inhibition differs with climatic conditions, variants, soils, and growth history. Such conditions complicate the understanding of the mechanism and optimization of plant-based corrosion inhibitor doses. Gallic acid, with the chemical name 3, 4, 5 tri-hydroxyl benzoic acid, is invariably present in considerable concentrations in plants25. It appears that this constituent of GA in plants’ products has significant effect in controlling the corrosion of metals exposed in different environments. An exhaustive literature revealed that except few references related to the studies on direct inhibition effect of GA, in majority of the publications its role in reducing the rusts on painted steels are reported. Shibata et al.26have discussed the mechanism of inhibition of GA in controlling the corrosion of steel in alkaline environment. Gallic acid is reported to resist radiation degradation and provide corrosion inhibition to carbon steel27. Apart from steel, GA was also tested for other metals such as aluminum, copper etc. It imparts no protection towards aluminum exposed in phosphoric acid28. Li et al., in a recent communication, compiled the progress of research on gallic acid in corrosion inhibition and rust removal protection of metals29. The literature search further revealed that the information related to the role of GA as inhibitor for chloride-induced corrosion of rebars is scarcely available.

During preliminary studies we noted that GA did not perform well when tested in neutral chloride and lime free pour solution. The inhibitive effect considerably increased in alkaline chloride and pour solution added with calcium chloride. These findings indicated that Ca ion and pH of the test environment played important role in boosting the inhibitive effect of GA. Calcium ion is known to act synergistically with many organic molecules to control corrosion of metals exposed in different environments30,31,32,33,34. In majority of the published literature, it is suggested that Ca ion precipitates as calcium hydroxide on the metals’ surface and provides barrier protection. This logic, however failed to explain the poor inhibitive effect of this inhibitor in neutral chloride and alkaline solution. These observations prompted us to investigate the effect of this inhibitor on corrosion of rebars embedded in concrete and mortars where lime is an essential component added in binder. This unique observation tempted us to investigate the effect of the inhibitor on the other properties of freshly prepared concrete mixtures and the long-term effects on the mechanical properties of mortars.

The aim of the present study is to elucidate the unique, interesting, and very useful information on role of gallic acid in combination of calcium ions on effectively inhibiting chloride induced corrosion of steel reinforcement bars exposed in simulated concrete pore solution as well as embedded in mortars. An exhaustive literature survey revealed that this new finding on role of calcium ions on performance of GA in controlling the chloride induced steel rebars corrosion was not reported earlier.

To accomplish the above objectives, the authors planned and conducted systematic experiments, postulated the mechanism of inhibition with convincing scientific discussion and explained the unique behavior of GA added to mortar at very low concentrations.

Experimental methods and materials

Test materials

Thermo-mechanically treated (TMT) rebar with a diameter of 16 mm was selected as the test material. After hot rolling, the rebar was subjected to quenching and tempering. Approximately 2 mm of its outer diameter was transformed into a tempered martensite rim. The inner core had a pearlite–ferrite structure. The chemistry of the steel rebar, as determined by inductively coupled-plasma-optical spectrometry (ICP-OES) and mechanical properties are tabulated in Table 1.

Appropriate lengths of the test specimens were cut from the single full-length rebar using a diamond-cutting machine under water-cooling to avoid localized heating during cutting. They were abraded on an abrading wheel to completely remove the mill scale from their surface. The surfaces of the rebar samples were polished with rough-to-fine grades of emery paper to remove visible scratches formed during the abrading. Subsequently, the surface was de-oiled using ethanol.

The mechanical properties of the steel rebars were tested by MTS machine without removing the ribs on the surface of bars.

Design of corrosion cells

To conduct electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and DC polarization experiments in chloride/alkaline and pore solutions, the de-scaled and abraded rebars of 150 mm in length were fitted in the electrochemical cell shown in Fig. 1. Two graphite rods of 8 mm diameter and of the same length as the rebar were also fitted horizontally in the corrosion cell. These rods were short circuited together with copper wire and used as the auxiliary electrode to run the electrochemical experiments. The test rebar was fitted 20 mm besides these rods in the cell, as shown in Fig. 1.

The purpose of fixing of two graphite rods in the corrosion cell was to ensure adequate surface area of the auxiliary electrode. The graphite rods and rebars’ ends emerging from the test cell were blocked with epoxy resin to make the cells leak-proof. The appropriate leads of the potentiostat cable were connected to graphite rods and rebar ends that were outside the cell. The detailed method for the preparation of the simulated pore solution (SPS), electrochemical cell geometry, and testing procedures were followed, as described in our previously published papers35,36. Saturated calomel electrode was used as the reference electrode for the measurement of potential.

Composition of the inhibitor

Laboratory grade 3, 4, 5 tri-hydroxyl benzoic acid, commercially known as GA (molecular formula C7H6O5, M.W. 170.1 g/mol) was purchased from E-Merck. Owing to poor solubility of the GA in water (11.9 g/L), it was dissolved in methanol (its solubility in this solvent was approximately 29 g/L)37. Twenty-five grams of GA in powder form was dissolved in 1000 mL of methanol under gentle stirring at 25–30oC in a glass bottle covered with a lid to avoid evaporation loss of the solvent. The resultant solution was left in the lid-covered bottle for 24 h to ensure complete miscibility and reaction of the components, if any. This solution was used as a stock solution to evaluate its effectiveness as an inhibitor for chloride-induced corrosion of the reinforcing steel rebars, for the compressive strength of cast mortar cubes, and for slump improvement, as detailed in the subsequent paragraphs. It is important to mention that the addition of alcohols to mortar affects the hydration of cement38. In the present study, the addition of methanol as a solvent in mortars was extremely low and unlikely to affect the properties of slump or other properties of mortars (for example, for the addition of 0.125 g of GA (its optimum concentration) in mortar with 100 g of cement, the added methanol in mortar was approximately 0.122 ml). Gallic acid is a weak organic acid with pKa values of 4.40 (carboxylic acid), 8.7, 11.4, and > 13 (phenolic OHs)39,40. Such a weak acidic compound added at very low concentrations (0.122% of weight of binder in mortars) is not expected to change alkalinity of pore solution.

Mortars

To test the efficacy of the GA inhibitor on chloride-induced corrosion, mortars embedded with reinforcement bars, as described in 2.1, were cast in the absence and presence of different concentrations of the inhibitor. The geometry of the mortar is shown schematically in Fig. 2.

To avoid the effect of counter electrode geometry on the polarization data, graphite rods with the same rebar diameter (16 mm) were cast in the mortar specimens (Fig. 2) and maintained parallel to the steel rebar. This graphite bar was used as a counter electrode during electrochemical studies. To avoid crevice attacks at the two ends of the rebar, a 15 mm length at both ends was coated with epoxy and Teflon tape. Below these coatings, a copper wire was soldered onto the surface of the rebars and tightly wrapped on the graphite rods. The wires protruding from the mortars acted as electrical leads for electrochemical study. Of the 150-mm length of the rebar samples, only 120 mm was exposed to the mortar. A cover of 25 mm thickness was provided for the steel rebars from all casting sides.

The mortars were prepared using ordinary Portland cement conforming to ASTM 150 C Type 1, water, and sand mixed in a proportion of 1:0.35:2, respectively. The sand particle size was within the range of 0.5–1.0 mm. To avoid soluble contamination in the sand, particularly halides and sulfates, it was washed twice with double-distilled water and dried in an oven at 130° C for 3 h. The casting and curing of the specimens were performed according to ASTM C192. Three sets of specimens were constructed, each embedded with rebars containing different concentrations of the GA inhibitor. The inhibitor concentrations were calculated based on the cement used to cast the mortar. The mortars were demolded after 24 h of casting and cured in a humidity chamber maintained at 95% RH and a 22 ± 2° C temperature until the age of 28 d. The mortars were subsequently subjected to wet/dry treatments, as detailed in the following sections.

Test methods

Electrochemical-impedance studies (EIS)

After 28 d of curing, the mortars were exposed to wet/dry treatment: 10 d in a 3.5% sodium-chloride solution, followed by drying in a laboratory environment for 15 d (temperature of the laboratory varied between 22 ± 2° C). This 25-d period of wet/dry treatment was considered as one cycle. It has been reported that the cyclic wet-dry treatment of mortars has an accelerating effect on the onset and propagation of corrosion on rebars surfaces, which simulates the actual conditions of field applications41. EIS tests were performed under wet conditions of the mortars at different wet/dry treatment cycles. The potentiostat used to run the EIS tests was calibrated with dummy cell. The standard practice described in ASTM G 106 − 89 was followed to verify algorithm and equipment for electrochemical impedance measurements. The tests were performed after different intervals of exposure of the samples by applying a 10-mV sinusoidal voltage at the open-circuit potential of the working electrode, while changing its frequency from 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz at 10 steps per frequency decade. The lowest studied frequency was fixed at 0.01 Hz as going below this value the experiment took impractically longer time to complete. The EIS data were analyzed using CMS 300 Software of M/S Gamry instrument. Kramer-Kroenig check was performed to ensure the quality of recorded spectra. The other test details for assessing the performance of rebars embedded in mortar are the same as those described in our earlier publications35,36.

Potentiodynamic studies

Potentiodynamic experiments were performed by scanning the potential at the rate of 0.1 mV/sec, polarizing the working electrode from − 1000 mV to + 1000 mV with respect to the open circuit potential. All the experiments were performed at room temperature of the laboratory (22 ± 2° C). Saturated calomel electrode (S.C.E.) was used as reference electrode to measure the potentials.

Characterization of corrosion products

Raman spectroscopy of the corrosion products collected from the surface of the embedded rebars after 37 cycles of wet/dry treatment was performed using dispersive micro-Raman spectroscope by applying a beam of Nd: YAG (Nd-doped yttrium aluminum garnet; Nd: Y3Al5O12) green laser with a wavelength of 532 nm to the samples. The laser was maintained at a low power to avoid the transformation of corrosion products due to the heating effect. The locations of the specimens were examined using an Olympus microscope at a magnification of 50x. Prior to the analysis of the samples, the instrument was calibrated using pure Si at a peak of 532 cm−1. The spectral peaks were analyzed using the Raman shift data library.

Workability tests

To determine the effect of GA on the flow of hydraulic-cement mortars, different mixes with varying concentrations of GA were mixed, and the followability of each mix was determined using a specified flow table according to ASTM C1437.

Determination of the compressive strength

The compressive strength of the mortar specimens was determined according to ASTM C109. Mortar cubes were cast with different concentrations of GA. The mortar cubes were then demolded after 24 h and maintained at 95% relative humidity and 22 ± 2 0C temperature until testing. Six mortar cubes were tested after 28 and 90 d for each concentration of GA. The average result for each group is presented and discussed in the discussion section.

Experimental results

Effect of GA inhibitor on chloride-induced corrosion of rebars

EIS studies

To assess the performance of the added GA inhibitor at different concentrations on the chloride-induced corrosion resistance of rebars embedded in mortars, EIS experiments were conducted for the control, the 0.25% methanol, and the formulated inhibitor at different concentrations (0.0625%, 0.125%, and 0.25%). The experiments were conducted at intervals of 6 cycles. After 36 cycles, the control and methanol mortars exhibited bleeding on their surfaces, indicating that the embedded rebar in these mortars experienced considerable damage on their surfaces. Therefore, the experiments were terminated after 37 cycles of treatment. To avoid the crowding of figures, the plots only for the shorter (6 cycles) and the longer (37 cycles) durations of exposure spanning more than 2.5 years are incorporated in this communication.

Bode and Nyquist plots for the shorter durations (6 cycles) are shown in Fig. 3(a-c). In these plots, the respective marker points are the experimental data, and the solid lines connecting the markers are the fitting lines using the appropriate equivalent circuits. The fitting of curves using the proposed model of circuit shown in Fig. 5 is good in all the cases. This aspect will be discussed in further detail in the following paragraphs. The log-modulus–log-frequency plots for this exposure duration are shown in Fig. 3(a). The impedance at the lowest studied frequency (10 mHz), which provides the value of the maximum impedance (Zmax) for a corroding interface, is greater for the inhibitor-added mortars than for the control mortar. Blending pure methanol in mortar had a negligible effect on Zmax compared to the control. The highest value of Zmax was noted at 0.125%, followed by 0.25% and 0.0625% GA-added mortars. The control and methanol-added mortars exhibited similar values of Zmax, indicating that the addition of methanol to the mortars by itself has a negligible effect.

(a) EIS impedance versus frequency plots for rebars embedded in mortar after 6 cycles of wet/dry treatment. (b) EIS phase shift versus frequency plots for rebars embedded in mortar after 6 cycles of wet/dry treatment. (c) Nyquist plots for rebars embedded in mortar after 6 cycles of wet/dry treatment.

Changes in the phase shift with the log frequency of the perturbation voltage for rebars embedded in mortars are shown in Fig. 3(b). The maxima in phase shift at lower frequencies (approximately 0.1 Hz) is attributed to the corrosion process. It was observed from the plots that the addition of the studied inhibitor to mortars increased the maxima of the phase angle. It was suggested that the stifling of corrosion was characterized by an increase in the phase-shift maxima in the EIS frequency-phase-shift plots42,43. The plots in Fig. 3(b) further reveal that the values of the phase-shift maxima for GA-added mortars are higher than those of the control mortar, indicating that the added inhibitor had protective effects on the corrosion of embedded rebars at all three concentrations. To supplement the impedance data plotted in Bode form, the data for the control, methanol and GA added mortars were also plotted in Nyquist form (real vs. imaginary impedance) and presented as Fig. 3(c). The figure reveals the same trend as noted for the performance of the added inhibitor shown in Fig. 3(a) and 3(b). The plots for the GA added mortars (top three distorted semi circles) exhibit bigger diameter than for control and methanol added mortars. Deformed and flattened semicircle in the Nyquist plots is usually interpreted as a deformed capacitance.

EIS log frequency–log modulus and log frequency–phase-shift Bode and Nyquist plots after longer durations of wet/dry treatment (37 cycles) are presented in Fig. 4(a), 4(b) and 4(c). In comparison to the shorter duration (6 cycles) of exposure, the concentration effects of GA on plots after 37 cycles were more pronounced on Zmax, but the trends were like those observed at the shorter duration of exposure (6 cycles, Fig. 3(a)). However, the values of Zmax are significantly higher for GA-added mortars after this duration of exposure compared to the shorter duration (6 cycles) of exposure.

(a) EIS impedance versus frequency plots for rebars embedded in mortar after 37 cycles of wet/dry treatment. (b) EIS frequency versus phase-shift plots for rebars embedded in mortar after 37 cycles of wet/dry treatment. (c) Nyquist plots for rebars embedded in mortar after 37 cycles of wet/dry treatment.

It is noted from the Bode plots that unlike shorter durations of wet/dry treatment, the maxima in the phase shifts in this case were not sharp, but slightly broadened (Fig. 4(b)). The broadening of the phase angle maxima is normally attributed to the greater protective shielding of the corroding interface by inhibitors44. A larger and broadened maximum was also attributed to the merging of the two-phase angle maxima in a closer frequency range45. The nature of Nyquist plots after this duration of exposure of 37 cycles (Fig. 4(c)) considerably differs from that of the shorter duration exposure plots (Fig. 3(c)). In the latter case, all the plots exhibit distorted semi circle. In contrast to it, the curves appear straight lines. Small diameter semi-circle in higher frequency region though exists there but appear to be masked. The plots for control and methanol added mortars overlapped.

The above descriptions of the results were based on a qualitative analysis of the EIS plots. This interpretation is more informative and useful with quantitative data that can be extracted from the simulated equivalent electrical circuit. Several permutations and combinations of the components of the electrical elements revealed that a circuit comprising a constant phase element (CPE), uncompensated resistance (R0), semi- infinite diffusion Warburg impedance (Wd) and charge-transfer resistance (Rct), schematically shown in Fig. 5, provided the best fit results with the least error. During fitting of the curves, the values of chi square (χ2) which is standard deviation for the fitting of experimental data in the model equation indicates the validity and acceptability of the fitted data. In all the cases, the chi-square values of the order of 10−4 were noted (not recorded in the table). The values of chi-square for a good fitting below 10−3indicate good fitting. Macdonald46,47, Ren et al.48 and Zhao et al.49 on the other hand opined that the chi-square factor may lead to biased results and 10−3criteria should not be a conclusive factor. It is suggested by the authors of references46,47,48,49 that Kramers-Kronig validity test with chi-square should be the acceptable criteria. The values of Kramers-Kronig validity test for the above system ranged between 10−6 and 10−7, indicating that the extracted data recorded in the Table 2 have least error.

In the schematic model shown in Fig. 5, CPE is constant phase element of the double layer. This element substitutes the double layer capacitor as in real life situation where the capacitive behaviour of the electrode is non-ideal. The deposition of the corrosion products on the metallic surface generates a non-homogeneous layer50,51,52.

CPE element is an empirically derived mathematical description of the experimental impedance data and is defined as53:

Yo in Eq. (1) contains capacitance information and “α” is an empirical constant and determines the characteristics of CPE. Depending on the nature of the corroding interface, the value of “α” can vary between 0 and 1. If interface behaves as a pure resistor when “α” = 0 and in case of a pure capacitor, “α” = 150,51.

Wdis semi-infinite diffusion Warburg impedance which arises under the condition of diffusion of electroactive species when mass transport takes place from the bulk solution to the metallic surface in the absence of corrosion products54,55. In the event of formation of corrosion products on the metal surface partially isolating it from the corrodent, the transmission line model is suggested56. Though we did not use this model in our data analysis, this model certainly provides useful information about the corroding interface. Because the Warburg component appears only at lower frequencies, its incorporation into the equivalent circuit underestimates the estimation of other EIS elements, namely R0, Y0, and Rct57. This parameter therefore was estimated separately and plotted as bar chart, as discussed in the upcoming paragraphs.

Different parameters of the above-described circuit, namely R0 (pore solution resistance), Rct (charge-transfer resistance), CPE exponent ‘α’, Yo (the element incorporating double-layer capacitance), provide useful information on the corrosion behavior of the exposed-steel rebars. The quantitatively extracted data by fitting experimental data in CPE model shown in Fig. 5 are recorded in Table 2. The data of the table show that the values of the series resistance (R0), which is related to the ionic conductance of the solution filling the pores of the mortars58 after 6 and 37 cycles of wet/dry treatments, as recorded in Table 2 differed considerably for the control and GA-added mortars. These values for the inhibitor-added mortars were significantly higher than those for the control mortars. This is more evident for mortars with longer duration of exposure (37 cycles) than for mortars with shorter duration of exposure (6 cycles). It should be noted that apart from the other soluble constituents that emanate from the concrete components and the added water, diffused chloride ions from external sources affect the ionic conductance of the pore solution. Significantly higher values of R0 for the inhibitor-added mortars, as noted from the data of Table 2, suggest that the added GA inhibitor, in addition to stifling the corrosion reactions at the rebar-concrete solution interface, also beneficially affects the porosity of mortars, rendering the concrete more impervious to the diffusion of chloride, moisture, and acidic gases. Further, the higher values of R0 for GA added mortars at longer duration of exposure (37 cycles) than those noted for shorter duration (6 cycles) is attributed to increased diffusion of GA in pore solution. This increased GA content in the pore solution interacted with other ionic species in the solution specially Ca++ to form sparingly ionizable products (discussed more in detail in discussion section of the communication) and increased the solution resistance.

The charge-transfer resistance (Rct), which is inversely proportional to the corrosion rate, is negligibly affected after the addition of methanol in mortars when compared with the control, both at 6 and 37 cycles of wet/dry treatment (Table 2). The considerable decrease in Rct at 37 cycles of treatment under these two conditions of embedded rebars is attributed to the increased concentration of diffused chloride at the corroding interface, resulting in enhanced chloride-induced corrosion. A significant improvement in Rct was recorded when the inhibitor was present at its optimal concentration (the Rct values in this case increased from 3.36 KOhm.cm2 recorded for the control to 81.93 KOhm.cm2 in the presence of 0.125% GA inhibitor at 37 cycles of wet/dry treatment). Furthermore, the Rct values at 37 cycles of treatment were invariably higher than those recorded at 6 cycles for all three concentrations of the inhibitor. This increased value may be linked to the dual role of the inhibitor, which densified the pores of the mortar and its adsorption at the metal/electrolyte interface.

It was considered important to study the effect of number of cycles of wet/dry treatment on change in values of Rct. Accordingly these data were computed at the interval of six cycles of wet/dry treatments. The extracted data are shown as bar chart in Fig. 6. The charts in the figure reveal that with increase in number of cycles of treatments Rct for control samples considerably decreases. The trend is similar also for methanol added mortars. This deterioration is attributed to increased concentration of chloride diffused from the test electrolyte that destabilized the corroding interface. The values of Rct for GA added mortars on the other hand remained either unaffected or moderately increased with increased number of cycles of treatment. As stated above this improvement may be attributed to dual role of the added GA inhibitor.

The electrochemical parameter Y0 (admittance) extracted from the data in Figs. 3 and 4 are also recorded in Table 2. This parameter is related to capacitance of the passive film formed on the surface of the reinforcement. The data recorded in Table 2 show that the trend of change of Y0 is opposite to that of Rct. The decrease in admittance indicates diminished electrochemical activity at the interface, which is related to the protective nature of the corroding interface. On the other hand, the higher value of Y0 is attributed to the porous nature of the film through which charge-transfer reactions occur. Under all the test conditions, this component is significantly lower for the inhibitor-added rebars than for the control rebar (Table 2), which is another indication that the added inhibitor controlled the corrosion reactions at the pore solution–rebar interface.

As stated above, the value of the fractional exponent “α” affects the CPE characteristics. It also provides clues as to whether the system is under capacitive or resistive corrosion control. The values of “α” for control and GA-added mortars at 6 and 37 cycles recorded in the table show that the values are close to 0.55. These results suggest that the corrosion reactions at the rebars’ surface were under Warburg diffusion control. This effect occurred due to the diffusion of chloride and oxygen through the oxide layer (rust) formed on the surface of rebars59. On the other hand, the values of ‘α’ for inhibited mortars are close to 0.80, indicating that the interface under this condition was under capacitive control.

The above results undoubtedly show that gallic acid effectively controlled the corrosion of chloride induced corrosion of rebars embedded in mortars. The inhibitive effect was more pronounced after longer duration of exposure when compared with control mortar (about 25-fold greater Rctvalue). The presence of adjacent -OH groups bonded to aromatic ring in structure of gallic acid is reported to enhance the adsorption of its molecules on oxide particles60 (structure of gallic acid is presented in Fig. 13 and will be discussed further in detail under forth coming paragraphs). This compound when added in an electrode-electrolyte system is expected to affect the Helmholtz layers. In view of this, it was interesting to study the role of gallic acid on double layer capacitance of the film formed on the surface of reinforcement bars. The capacitance (Cdl) for the interfaces where CPE is in series with resistor (R0) can be calculated by using the following formula61:

The Cdl results computed using the Eq. (2) are recorded in Table 2 for 6 and 7 cycles of wet/dry treatments. The control samples including that added with methanol exhibited considerably high Cdl values (46 ΩF cm−2) which is consistent with the results reported in literature for steel rebars embedded in chloride added concrete and alkaline solution62,63.

The addition of gallic acid in mortars is noted to reduce the values of Cdl. After longer duration of exposure (37 cycles), the Cdl values range from 5 to 8 µF cm−2 for the three studied concentrations of gallic acid added in the mortars. These values are significantly smaller than the control and methanol added mortars. Although the double layer capacitance values for gallic acid inhibition on steel in concrete are not available in literature but the present results of Cdl (5 to 8 µF cm−2) are closer to those reported for other inhibitors inhibiting carbon steel in alkaline environment64.

From the Cdldata of control and GA inhibited interface, it is possible to compute the accessible area (AA) on the surface of rebars through the pores of protective film of GA by using the following formula64:

Taking the average value of Cdl for the three studied concentrations as 7.17 µF cm−2 and that of control sample (46 µF cm−2) the accessible area is 15%. This value is in the range of previously reported data (12%) by Baux et al. for inhibitive effect of octadecylamine on steel exposed in alkaline solution.

The % inhibition efficiency of GA using the polarization resistance (Rp) which is equal to (Rct – R0)65, was computed using the relation:

The computed data of the efficacy of the studied GA inhibitor at the three concentrations as recorded in Table 3 exhibit that it imparts the protection of the order of 95–96% at 37 cycles of wet dry treatment of mortars. This range of inhibition efficiency of an inhibitor is considered very effective in controlling the corroding interfaces.

The estimated values of Cdl for control and inhibited interfaces recorded in Table 2 were used to compute the thickness of film formed on the surface of embedded rebars. The thickness data for the surface film were computed by using the usual formula for capacitor considering uniform permittivity along the film thickness:

Where ε0= 8.8542 × 10−14 F cm−1is dielectric constant of vacuum, ε is the permittivity, and t is thickness of the surface film. Due to non-availability of permittivity data for the GA film in literature, the data for the lepidocrocite phase of oxide formed on the surface of rebars as determined by XRD, was used to compute the thickness. The appearance of strong peak of lepidocrocite on the surface of control and multiple peaks of hematite on the surface of GA were considered to compute the thickness of the film. Taking the dielectric constant value of lepidocrocite = 2.6 and that for hematite = 4.5 as reported in literature66,67, the thickness of the passive film was estimated using Eq. (5) and recorded in Table 3. Film thicknesses for control samples at 6 and 37 wet/dry cycles are respectively 0.59 and 0.49 nm. In comparison to these, respective thicknesses of GA film were considerably higher and varied from 4.65 to 8.56 nm. The data further show that the increase in exposure time had little effect on film thickness of GA. It is to be noted that the thickness of film on metals surfaces greatly varies on measurement techniques, test environment, temperature etc. An exhaustive literature search revealed that the majority of information on film thickness on steel bars pertain to their exposure either in simulated pore solution or in alkaline environments. Thus, Ghods et al. using XPS depth profiling technique reported the thickness of 5 nm for the passive film on steel rebars exposed in saturated lime solution66. Al-Negheimish et al., employing the same method, found the film thickness of 7 nm for carbon-steel bars exposed in simulated pore solution67. The results for the film thickness determined by electrochemical methods are a bit lower than those computed by XPS depth profiling. Lv and Li employing Mott–Schottky analysis reported the thickness of 0.1 to 0.9 nm for steel in contact of different pH of simulated concrete pore solution68. Similarly, Ismail and Ohtsu using impedance technique found the double layer capacitance (Cdl) = 12 µF.cm−2for steel rebars embedded in concrete. This translated to film thickness of 1.9 nm69. The thicknesses of film formed on steel rebars’ surface during the present study are reasonably in good agreement with the data reported by the above referred researchers.

Potentiodynamic polarization

One set of rebars embedded in the control and 0.125% GA-inhibited mortars were potentiodynamically polarized after 37 wet/dry treatment cycles. The test electrolyte was 0.6 mol/L water solution of sodium chloride. These plots are shown in Fig. 7. The plot for only one concentration of GA added mortar i.e. only optimum concentration (0.125%) is given in this figure with that of control mortar to have clear visibility from the control mortars. In the presence of the other studied concentrations of GA, the nature of the potentiodynamic curves were very similar to that of the optimized concentrations. Many distinct differences in the features of the two plot types were recorded. The anodic branch of the polarization curve for the GA-inhibited rebar is bodily shifted to the lower current-density region. In addition, the curve at approximately 0.15 V exhibited passivation behavior. The current density in the corresponding curve for the control rebar exhibited an exponential increase in current without any passivation behavior. The cathodic polarization curve for the inhibited rebar was more polarized than that of the control rebar (Fig. 7). These observations suggest that GA added to mortars effectively stifled anodic and cathodic reactions and inhibited the corrosion reactions occurring at the interface of the embedded rebars and pore solution.

Surface appearance of the investigated rebars

All the above-described findings and their deliberations were based on indirect-test results. The visible appearance of the test objects after longer durations of aggressive tests provides convincingly acceptable and foolproof evidence for the efficacy of any technique used to control corrosion damage. After 37 wet/dry cycles, the mortars were broken to retrieve the embedded rebars; their digital images are shown in Fig. 8. The photographs show that the rust on the control rebar was spread all over its surface. The addition of 0.0625% GA to the mortars significantly reduced the chloride attack on their surfaces. The rebar embedded in the 0.125% GA-inhibited mortar appeared completely protected, showing no trace of rusting on its surface. The addition of 0.25% of the inhibitor to the mortar exhibited similar effect as noted for the 0.125% addition. A small spot of the rust at the bottom of this rebar was due to the formation of differential aeration cells and the shielding effect of Teflon tape that did not allow migration of GA from the mortars to the surface of the embedded rebar. The above results indicate that an optimum dose of GA in mortars is valuable for achieving complete protection of the embedded rebar.

Effect of GA inhibitor on workability and compressive strength

The workability of fresh mixes and the compressive strength at the hardened stage are important parameters to be examined. The effects of the formulated inhibitor at different concentrations on the workability of the mortar mixes are presented in Table 4. It is noted from the data in the table that a small addition of the inhibitor (0.0625%) to the mortar mix increased the workability (it increased from 25% under controlled conditions to 39% after the addition of the inhibitor). At a GA concentration of 0.125%, the workability further increased to 43%. A higher dosage of the inhibitor beyond 0.125% GA resulted in marginal additional improvement. Increased workability is an added advantage of the inhibitor, as it enhances the quality and productivity of the work.

The strength of the control cubes and those of the inhibitor added at different concentrations for 28 and 90 d of aging are summarized in Table 4. The strength remained unaffected up to 0.25% of the added inhibitor after 28 and 90 d of aging. Beyond this concentration, it decreased significantly. This is attributed to the retardation effect of GA on the hydration of cement, and the consequent formation of C-S-H gel. Aromatic carboxylic acids with adjacent hydroxyl groups (such as GA) have strong chelating effects on Ca++. This results in the formation of less permeable and more adhesive gel coatings around the cement grains, which interfere with cement hydration and the strength development of mortar [58,70]. The negligible effect on strength at lower concentrations of GA is due to the inadequate chelating effect of the added inhibitor with Ca++. These results clearly show that a GA dosage of 0.125% is the optimum dosage considering workability, strength, and corrosion inhibition.

Morphology of the rebar surfaces

The study of the morphologies of the corrosion products provides vital information on the corrosive or protective effects of the surrounding environment and complements the findings obtained using other techniques. The major corrosion products on steel surfaces embedded in mortars are primarily oxyhydroxides and oxides of iron, which differ in shape and structure depending on the environment surrounding the steel, that is, pH, temperature, oxygen, moisture, anion, and cation availability. These oxyhydroxides and oxides have morphologies such as honeycomb, globular crystals, flowery, cotton balls, micaceous, and plate-like structures. Scanning-electron microscopy microphotographs of the rust/film formed on the surface of the control and GA-inhibited rebars after 37 cycles of wet/dry treatment are presented in Figs. 9, 10 and 11. To achieve better resolution, small inserts of microphotographs recorded at higher magnifications (x5000) were also embedded in the top-right side of the figures. The rust formed on the control sample exhibited cellular structure with relatively uniform pore size, with some cracks in the rust layer (Fig. 9). These types of structures contain porous films consisting of iron oxyhydroxides specially lepidocrocite (λ-FeOOH) and akageneite (β-FeOOH)69,70. In the presence of 0.0625% GA, the image shown in Fig. 10exhibits that cellular structure is still retained. As stated above, such structures are attributed to the presence of oxyhydroxides and oxides of iron71,72. An increase in the concentration of GA (0.125%) in the mortar did not result in any trace of rust (as described in the following section). The morphology of the surface of this rebar had varying shape and looked as agglomerated particles (Fig. 11). In this case, the morphology of the layer is a largely uniform deposition of some films with the least flaws and fissures. At higher magnifications (x2000 and x5000), features of oxides are noted. Such morphologies are reported for maghemite73.

Phase identification of corrosion products and passive layer

The corrosion products collected from the surface of the rebars embedded in the control mortars after 37 cycles of wet/dry treatment were analyzed using the Raman spectroscopic technique. Because no corrosion product was formed on the 0.125% GA-inhibited rebar, a small portion of its surface, which was bluish in color, was placed in the Raman instrument test chamber and experiments were conducted. The resultant spectra for the rust of the control sample and GA-inhibited rebar surface is presented in Figs. 12 and 13, respectively. The Raman shifts of the corrosion products noted in the spectra and their attributes are listed in Table 5. These peaks were identified from Raman shift data reported in the literature74. The data in the table reveal that the major phases detected in the control rust corresponded to lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH) and akageneite (β-FeOOH). Normally, multiple phases of rust are formed on the surface of steel rebars embedded in concrete. However, their nature differs depending on the prevailing conditions during the corrosion reactions at the pore solution–steel interface. The surface of the GA-inhibited rebar exhibited a strong maghemite peak, with some weak hematite peaks. A very perceptible and intense maghemite peak with a strong Raman intensity indicates its major content on the surface of the GA-inhibited rebar. In GA inhibited passive film, the multiple Raman peaks of hematite (α-Fe2O3) and that in control sample the peaks of lepidocrocite (λ-FeOOH) suggest that the film was more stable on former samples (GA added) than the latter one (control condition). Thermodynamically α-Fe2O3phase of iron oxide is more stable than λ-FeOOH (Gibbs free energy of formation for hematite and lepidocrocite are reported as −742 kJ/mol and − 480.1 kJ/mol respectively)75.

Discussion

The above results show that the GA inhibitor effectively controlled the chloride-induced corrosion of the reinforcing steel rebars. It is well known that electronic and molecular structures and their interactions with the corroding interface control the efficacy of corrosion inhibitors added to the environment. The attributes of the inhibitors also affected the hydration of cement. The mechanism of GA inhibitor in improving the corrosion resistance and hydration of cement and hence improved fluidity is discussed under the following separate sub-headings.

Mechanism of corrosion inhibition of rebars

A literature search revealed that information on the inhibitory effect and mechanism of action of GA, especially in concrete environments, is scarce. The majority of studies have focused on the use of extracts of medicinal plants, fruits, and leaves for the corrosion inhibition of metals. Different components of plants are rich in polyphenol compounds, including GA75. It is suggested that these compounds provide a protective effect against the corrosion of metals exposed to corrosive environments by their chemical or physical adsorption through the carboxylate and hydroxyl groups present in their structures. Little information is available on whether these protective effects against corrosion are due to a specific compound or conjoint action of multiple phases present in plant extracts. Apart from other polyphenol compounds, GA remains invariably present in varying concentrations in the fruits and leaves of medicinal plants that provide protection against corrosion. In view of this, we believe that this compound also plays a crucial role controlling the corrosion reactions of metals and alloys in contact with different environments. In comparison to the acidic and neutral solutions, data for GA on corrosion inhibition and the mechanism of action in alkaline environments are scarcely available. Shibata et al.26 suggested that GA added to an alkaline solution, owing to its reducing properties, transforms unstable Fe (OH)3 formed on the steel surface to a relatively more stable passive film of magnetite (Fe3O4). Etteyeb and Novoa76 reported that extracts of leaves of Eucalyptus Globulus, trunks of Punica Granatum, and Olea Europaea rods inhibited the chloride-induced corrosion of steel in a simulated concrete-pore solution. The inhibitory effect was attributed to the chelating effect of the plant extracts with Fe++ions in the steel. The mechanisms for corrosion inhibition by plant extract compounds, including GA, suggested by most authors, are based on mechanisms proposed by health and medical researchers, who assert that these compounds have beneficial health effects owing to their chelating actions on free radicals and their antioxidant properties77. The proposed mechanisms of corrosion inhibition by these compounds may be true in neutral and acidic environments. However, in alkaline solutions, such as in concrete environments, many of the polyphenol compounds undergo a series of irreversible transformations, yielding newer compounds and radicals than the parent structures. Gallic acid is a weak polyprotic acid with four protons that can readily interact with hydroxyl ions present in the concrete-pore solution to form gallate radicals, as shown in Fig. 1478.

According to the above reaction scheme, GA loses all four protons in alkaline environments, forming negatively charged gallate ions. The very strong inhibitory effect of GA on the chloride-induced corrosion of rebars (almost complete protection as evidenced from Fig. 8) is probably due to the gallate ions on the iron surface. As described in Sect. 3.4, Raman spectroscopy did not yield any peak of iron gallate (the Raman peaks of iron gallate in the Raman spectra are reported at 1579 cm−1 and 1430 cm−1)78. This may be due to the presence of a very thin gallate layer. Being an organic molecule, it is also possible that the gallate film decomposed due to the heating effect of the falling laser on the surface of the protective film. To probe this further, the rebar surfaces were subjected to energy-dispersive–X-ray analysis (EDX). The detected elements and their concentrations are listed in Table 6. Fe and O were present in considerable amounts on the surfaces of the inhibited and control rebars. The conspicuous presence of Ca at higher concentrations on the surface of GA inhibited rebar vis-à-vis the control rebar, indicating that this element helped gallate ions to develop a protective surface film on the steel surface. It is important to mention that EDX analysis does not provide accurate results but provides strong clues about the presence of elements and their approximate concentrations.

The presence of oxygen and iron in the analysis results for GA-inhibited rebar suggests that its surface was covered with an invisible thin oxide film of iron. The oxygen content (31%) on the surface of the GA-inhibited rebar was closer to the value of the maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) phase of iron oxide (30%), whereas in the control sample, it was 39% (closer to the value of the iron oxyhydroxide (FeOOH) phases of iron oxide). These results corroborate the findings of Raman spectroscopy recorded in Figs. 12 and 13; Table 5.

In GA inhibited and control sample rusts, the strong Raman peaks of maghemite and lepidocrocite (258 cm−1) + akageneite (387 cm−1) are recorded. Amongst these oxides, maghemite is thermodynamically the most stable phase (the standard Gibbs free energy of formation for akageneite, lepidocrocite and maghemite are reported as −481.7, −480.1and − 727.9 kJ/mol respectively)79,80. Presence of very strong Raman peak of maghemite on the surface of rebar embedded in GA added mortars indicates that film comprising of this stable phase of the oxide was primarily responsible for extraordinary protection imparted by GA. Gallic acid is reported to inhibit the transformation of lepidocrocite to magnetite80. The absence of unstable and non-protective phases of lepidocrocite and akageneite in passive film of GA inhibited rebars’ surface was probably due to this effect.

To confirm the role of Ca++and alkalinity on the inhibitive performance of GA, a set of qualitative and quantitative tests was performed. In 100 mL of an alkaline water mixture (0.16 M NaOH + 0.55 M KOH (referred as alkali solution; many researchers use it as simulated concrete-pore solution))82,83, 0.050 g of GA was dissolved. As shown in the digital images presented in Fig. 15, the addition of GA to the alkali solution changed its colour from transparent to pale yellow (Image # 3 of Fig. 15). The pH of the solution after the addition of GA did not change and remained constant at 13.2 as noted for the alkaline solution before blending of GA. After the addition of 0.02 g of calcium chloride to this solution, the colour of the solution changed from pale yellow to sharp blue (Image # 4). In a separate experiment, 0.05 g GA added in 0.02% (w/v) solution of calcium chloride (pH = 6.8) had no effect on colour (Image # 2). These results suggest that alkalinity and the combined effect of alkalinity and calcium ions both play crucial roles in the formation of complex compounds.

To collect quantitative evidence for the role of Ca++ ions on inhibitive performance of GA, electrochemical-impedance experiments were performed exposing steel rebars in a simulated concrete-pore solution (0.16 M NaOH + 0.55 M KOH dissolved in doubly distilled water) and added with 0.6 M Cl− (as sodium chloride), GA, and Ca++ (derived from calcium chloride). Although the tests were performed using different concentrations of GA and Ca++, the results for only one concentration are shown.

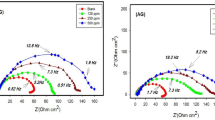

The impedance plots in Bode (changes in the impedance and phase shift with frequency) and Nyquist (real vs. imaginary impedance) forms for the rebars exposed to different test electrolytes are presented in Fig. 16(a), (b), and (c). The experiments were performed after exposing the rebar samples to the test electrolytes for 240 h, which was sufficient for the formation of a stable passive film on the metal surface15,16. Figure 16 (a) and (b) show that the nature of the plots for the control (SPS + Cl−), control + 0.05% GA, and control + 0.05%GA + Ca++ are largely similar. The impedance values for the exposed rebars at the lowest studied frequency (10 mHz), which inversely relates to the proneness toward the reaction rate at the corroding interface, significantly varied for the different test electrolytes. Furthermore, this value of impedance is significantly increased after the addition of Ca++ with GA, indicating that Ca++ provided a synergistic effect on the inhibition of corrosion by GA. To ensure the reproducibility of the results, each of the experiments were repeated three times and the plots and values were found closely matching with respective corroding interface.

(a) Log-frequency-normalized impedance Bode plots for steel rebars exposed to different test electrolytes for 240 h. (b) Log-frequency-phase-shift Bode plots for steel rebars exposed to different test electrolytes for 240 h. (c) Nyquist plots for plots for steel rebars exposed to different test electrolytes for 240 h.

The Bode plot showing the change in phase shift with log frequency presented in Fig. 16(b) exhibits a single time constant in the frequency range of 1–10 Hz. At a higher frequency, the phase shift for all three sets is zero, which corresponds to the pure resistance imparted by the test electrolyte between the login capillary of the reference and test electrodes.

The Nyquist plots (Fig. 16(c)) also suggest that GA in combination with Ca++ provides very effective synergistic inhibition. In all the cases distorted semi-circles are noted. This effect is more pronounced for control and control + GA samples, indicating that the capacitor in the latter condition was more defective.

The quantitative data from the impedance plots for blending of different concentrations of Ca2+ (0.1, 0.2 and 0.25%) with 0.125% GA were extracted by fitting the data in simulated electrical circuit comprising of uncompensated resistance (R0), charge transfer resistance (Rct) and constant phase element (CPE) as shown in Fig. 17. The best fitting results with very low value of χ2 are summarized in Table 7. The results of the table show that Ca2+ ion with GA has considerably boosted its efficacy. GA in absence of Ca2+ has marginally improved the charge transfer resistance (it enhances the Rct from 11.80 to 74.38 Kohm.cm2). In combination of Ca2+ the improvement is phenomenal. The charge transfer resistance in the presence of GA + 0.20% Ca2+ is substantially improved (about 50 times higher in comparison to control sample). The double layer capacitance (Cdl), %IE, and thickness (t) of film formed on the rebars surface were estimated using Eqs. (2, 4, 5) and the results are recorded in Table 7. It is noted from the data recorded in the table that Cdl computed in pore solution for control as well as inhibited environments are smaller in comparison to mortars as observed in Sect. 3.1.1 of this communication. It appears that plenty availability of GA and Ca2+ present in pore solution imparted better protection to the rebars surface. It is also reflected on IE and thickness of the surface film. Higher thickness of film in control sample (3.82 nm) noted in pore solution than the mortar sample (0.49 nm, Table 3) is attributed to shorter duration of exposure in the former case.

The above results strongly suggest that the presence of Ca++ in the test electrolyte improves the inhibitive performance of GA. Based on the above observations and findings, the inhibition mechanism of GA on the chloride-induced corrosion of rebars embedded in concrete mortars can be understood from the schematic presented in Fig. 18. In this schematic, the symbol  indicates the maghemite film formed on the rebar surface. Maghemite attains a negative charge on its surface in alkaline solutions86. The sign

indicates the maghemite film formed on the rebar surface. Maghemite attains a negative charge on its surface in alkaline solutions86. The sign  represents a calcium cation produced during the hydration of cement, and icon

represents a calcium cation produced during the hydration of cement, and icon  represents de-protonated form of GA. The schematic presented in Fig. 18 suggests that the Ca2+ present in the concrete-pore solution acts as a bridge between the steel surface and gallate ions. In the absence of calcium ions, the negatively charged gallate should have a negligible effect on controlling the corrosion of rebars covered with negatively charged maghemite film, as proposed in the schematic. This proposition is supported by the results of the electrochemical tests shown in Fig. 16 (a-c) and results of Table 7.

represents de-protonated form of GA. The schematic presented in Fig. 18 suggests that the Ca2+ present in the concrete-pore solution acts as a bridge between the steel surface and gallate ions. In the absence of calcium ions, the negatively charged gallate should have a negligible effect on controlling the corrosion of rebars covered with negatively charged maghemite film, as proposed in the schematic. This proposition is supported by the results of the electrochemical tests shown in Fig. 16 (a-c) and results of Table 7.

Mechanism of improvement of workability

To achieve satisfactory workability, the water-to-cement ratio to cast mortar is commonly maintained at 0.5. However, this ratio adversely affects the properties of the cast structures. The GA inhibitor enhanced the increase in slump at w/c ratios as low as 0.35, as shown in Table 4. This improvement may be explained by the transformation of GA into gallate ions, as shown in Fig. 14. Most cements require approximately 25% water with respect to their dry weight for complete hydration. However, to achieve good workability, more than 50% water is added to prepare the mixture. This is because the majority of added water is entrapped in agglomerated-cement particles in the mixture. Oppositely charged particles electrostatically attract each other and form agglomerates. These agglomerates entrap a significant amount of water. The gallate ions (Fig. 14) formed by the deprotonation of GA have four negative charges. These ions neutralized the positively charged particles present in the mixture. They also repelled negatively charged particles, which discouraged flocculation. The water released from the flocculated particles improved the workability of the mixture.

The compressive strength of the mortars in the presence of GA remained unchanged up to 0.25% of its addition to the mixture (Table 4). At higher concentrations (0.5% and higher), the strength decreased considerably. This deterioration may be attributed to the retarding effect of gallate ions on cement hydration. With the development of hydration, the concentration of Ca++ions on the surface of the hydration product increased. The cement particles attained a negative charge on their surface owing to the ionization of silanol in an alkaline solution82:

The Ca++ ions released due to the hydration of cement adsorb the silanol and develops a positive charge:

Gallate ions with negative charges interact with positively charged silanols, forming a complex that shields the silanol particles and discourages their hydration.

At higher concentrations of GA, the excess gallate ions formed in the pore solution interacted with calcium ions to form chelates. Such sequestration has been reported to reduce the availability of Ca++in the pore solution and hamper cement hydration83. Thus, the scarcity of C-S-H gel adversely affected the strength of the mortars.

Conclusion

The study findings suggest that the addition of GA to concrete mortars at an optimized concentration fully controls the chloride-induced corrosion of steel rebars. The alkalinity of concrete and Ca++ liberated from the hydration of cement boosted the inhibitive performance of GA. It was suggested that this compound undergoes irreversible transformation in alkaline environments, forming negatively charged gallate ions. The Ca++ of the pore solution acts as a binding bridge between the negatively charged maghemite film on the rebar surface and the gallate ions. Electrochemical-impedance spectroscopy and anodic polarization studies confirmed this hypothesis. The results of this investigation further confirmed that GA improves the workability (plasticizing effect) of mortar. It is suggested that the improvement in workability is due to the adsorption effect of gallate ions on the cement particles, which discourages agglomeration, releases entrapped water, makes it available, and allows the cement particles to move freely. The added GA inhibitor at a dosage of up to 0.25% maintained the short-duration (28 d) and long-duration (90 d) compressive strengths of the hardened mortar.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding authorupon reasonable request.

References

Ormellese, M., Lazzari, L., Goidanich, S., Fumagalli, G. & Brenna, A. A study of organic substances as inhibitors for chloride induced corrosion in concrete. Corros. Sci. 51, 2959–2968 (2009).

Ress, J., Martin, U., Bosch, J. & Bastidas, D. M. pH-triggered release of NaNO2 corrosion inhibitors from novel colophony microcapsules in simulated concrete pore solution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12, 46686–46700 (2020).

Génin, J. M. R., Dhouibi, L., Refait, P. & Abdelmoula, M. Influence of phosphate on corrosion products of iron in chloride-polluted-concrete-simulating solutions: Ferrihydrite vs. green rust. Corrosion 58, 467–478 (2002).

Soeda, K. & Ichimura, T. Present state of corrosion inhibitors in Japan. Cem. Concr Compos. 25, pp117–122 (2003).

Tritthart, J. Transport of a surface-applied corrosion inhibitor in cement paste and concrete. Cem. Concr Res. 33, 829–834 (2003).

De Gutierrez, R. M. & Aguirre, A. M. Durabilidad Del hormigón armado expuesto a condiciones agresivas. Mater. Constr. 63, 7–38 (2013).

Bastidas, D. M., Martin, U., Bastidas, J. M. & Ress, J. Corrosion Inhibition Mechanism of Steel Reinforcements in Mortar using Soluble Phosphates: a critical review. Materials 14, 6168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14206168] (2021).

Mohamed, A., Visco, D. P. Jr & Bastidas, D. M. Sodium Succinate as a Corrosion Inhibitor for Carbon Steel Rebars in simulated concrete pore solution. Molecules 27, 8776. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27248776 (2022).

Bastidas, D. M. et al. Comparative study of three sodium phosphates as corrosion inhibitors for steel reinforcement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 43, 31–38 (2013).

Maria Craido, D. M. et al. Precipitation mechanism of soluble phosphates in mortars. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 23, 167–172 (2019).

Mohamed, A., Martin, U. & Bastidas, D. M. Adsorption and Surface Analysis of Sodium Phosphate Corrosion Inhibitor on Carbon Steel in simulated concrete pore solution. Materials 15, 7429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217429 (2022).

Mohamed, A., Visco, D. P. Jr & Bastidas, D. M. Effect of cations on the activity coefficient of NO2/NO3 corrosion inhibitors in simulated concrete pore solution-An electrochemical thermodynamics study. Corros. Sci., 110476. (2022).

Ress, J., Martin, U., Mosch, J. & Bastidas, D. M. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 41 46686–46700. (2020).

Elsener, B., Angst, U. & Admixtures, C. Corrosion inhibitors for Reinforced Concrete, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100693-1.00014-X

Hu, J. Y., Zhang, S. S., Chen, E. & Li, W. G., Constr. Build. Mater., 325 126718. (2022).

Mohamed, A., Visco, D. P. & Bastidas, D. M. Significance of π–Electrons in the Design of Corrosion Inhibitors for Carbon Steel in Simulated Concrete Pore Solution, CORROSION,77 pp976–990. (2021).

Sastri, V. S. Corrosion Inhibitors (John Wily & Sons. Inc., 1998).

Chinnici, F., Bendini, A., Gaiani, A. & Riponi, C. Radical scavenging activities of peels and pulps from cv. Golden Delicious apples as related to their phenolic composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52 (15), 4684–4689 (2004).

Tianlai Xia, Y. et al. Natural Compounds Gallic Acid Derivatives for Long-Life Li/Na Organic Batteries, ChemEletrochem, 6 pp 4765–4772. (2019).

Keny, S. J., Kumbhar, A. G., Thinaharan, C. & Venkateswaran, G. Gallic acid as a corrosion inhibitor of carbon steel in chemical decontamination formulation. Corros. Sci. 50, 411–419 (2008).

Ivan Pradipta and Daniel Kong. Natural organic antioxidants from green tea form a protective layer to inhibit corrosion of steel reinforcing bars embedded in mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 221,, 351–362 (2019).

Etteyeb, N. & Nóvoa, R. Inhibition effect of some trees cultivated in arid regions against the corrosion of steel reinforcement in alkaline chloride solution. Corros. Sci. 112, 471–482 (2016).

Muran, A. & Osuga, S. Prevention of stress corrosion cracking in steel product. Japan Patent # JP9222180A (1980).

Favre, M. & Landolt, D. The influence of gallic acid on the reduction of rust on painted steel surfaces. Corros. Sci. 34, 1481–1494 (1993).

Karaconji, B. et al. Comparative Study on the Phenolic Fingerprint and Antioxidant Activity of Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo L.) Leaves and Fruits. Plants 11 25. (2022).

Shibata, Y. et al. Mechanism of corrosion inhibition of mild steel by gallic acid in alkaline solution (pH = 11). Denki Kagaku. 61, 992–999 (1993).

Kwolek, P. et al. Gallic acid as a potential green corrosion inhibitor for aluminum in Acidic Solution. Metals 12, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12020250 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Progress of research on gallic acid in corrosion inhibition and rust removal protection of metals, Anti-Corrosion Methods and Materials, https://doi.org/10.1108/ACMM-04-2023-2784. and Effect of Oxygen, Chlorides, and Calcium Ion on Corrosion Inhibition of Iron by Polyphosphates, J. Electrochem. Soc. 102 (1955) 59, DOI (2023). https://doi.org/10.1149/1.2429995

Jiang, X., Zheng, Y. G., Qu, D. R. & Ke, W. Effect of calcium ions on pitting corrosion and inhibition performance in CO2 corrosion of N80 steel. Corros. Sci. 48, 3091–310810 (2006).

Tweek, M. K. & Abdulsada, S. A. Synergistic effect of inhibitors on corrosion of reinforced concrete structures according to American Concrete Institute standards. Zastita Materizala. 65, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.62638/ZasMat1105 (2024).

Bing Lin, J., Tang, Y., Wang, H., Wang & Zuo, Y. Study on synergistic corrosion inhibition effect between Calcium Lignosulfonate (CLS) and inorganic inhibitors on Q235 Carbon Steel in Alkaline Environment with cl. Molecules 25(2020), 4200, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25184200

Ahmed, A. M. Amin Sherif and Ashraf Mohamed, current and emerging trends of inorganic, organic and eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors. RSC Adv. 14, 31877 (2024).

Hussain, R. R., Alhozaimy, A., Al Negheimish, A., Al-Zaid, R. & Singh, D. D. N. Mechanism of Nucleation and Growth of Passive Film on Steel reinforcing bar at different durations of its exposure in concrete pore solution at Nanoscale. ACI Mater. J. 112, 1–12 (2015).

Alhozaimy, A. A. N. A. & Hussain, R. R. J. K. Singh and D. D. N. Singh. Pitting susceptibility of concrete reinforcing steel bars having manganese sulphide inclusions,114 441–451. (2017).

Daneshfar, A., Ghaziaskar, S. & Homayoun, N. Solubility of gallic acid in methanol, ethanol, water and ethyl acetate. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 53, 776–778. https://doi.org/10.1021/je700633w (2008).

Singh, N. B. & Rai, S. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol on the hydration of cement with rice husk ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 31, 239–243 (2001).

Solbert, N. P. Ionization of flavanols and dihydro flavanols. Tetrahydron 33, 821–824 (1977).

Ji, H. F., Zhang, H. Y. & Shen, L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16 4095–4098. (2006).

Yeomans, S. R. Performance of Black, Galvanized, and epoxy-coated reinforcing steels in chloride-contaminated concrete. Corrosion 50, 72–81. https://doi.org/10.5006/1.3293496 (1994).

Mansfeld, F., Lin, S., Kim, S. & Shih, H. Pitting and surface modification of SIC / AI. Corros. Sci. 27, 997–1000 (1987).

Mansfeld, F. & Shih, H. Detection of pitting with electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 135, 1171–1172 (1988).

Gong, Z., Peng, S., Huang, X. & Gao, L. Investigation the corrosion inhibition effect of itraconazole on copper in H2SO4 at different temperatures: combining experimental and theoretical studies. Materials 11, 2107 (2018).

Mahmoud, A. et al. Cu-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles for Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensing. Molecules, MDPI, 26 pp.929. (2021).

Macdonald, J. R. Impedance spectroscopy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 20, 289–305 (1992).

Macdonald, J. R. Impedance spectroscopy: Old problems and new developments. In: Gabrielli, C., ed. Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Electrochim. Acta 35 pp1483-1492. (1990).

Ren, P. et al. Diagnosis of water failures in proton exchange membrane fuel cell with zero-phase ohmic resistance and fixed-low-frequency impedance. Appl. Energy. 239, 785–752 (2019).

Zhao, L., Pei, H. D. F., Wei, P. M. X. & Zhou, J. A Comparative Study of Equivalent Circuit Models for Electro-Chemical Impedance Spectroscopy Analysis of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Energies 15, p386. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15010386 (2022).

Lebrini, M., Lagrenée, M., Vezin, H., Traisnel, M. & Bentiss, F. Experimental and theoretical study for corrosion inhibition of mild steel in normal hydrochloric acid solution by some new macrocyclic polyether compounds. Corros. Sci. 49, 2254–2269 (2007).

Liu, Z. Y., Li, X. G., Du, C. W. & Cheng, Y. F. Local additional potential model for effect of strain rate on SCC of pipeline steel in an acidic soil solution. Corros. Sci. 51, 2863–2871 (2009).

Zoltowski, P. On the electrical capacitance of interfaces exhibiting constant phase element behavior. J. Electroanal. Chem. 443, 149–154 (1998).

MacDonald, J. R. & Spectroscopy, I. Emphasizing Solid Materials and Systems (Wiley, 1987).

Taylor, S. R. & Gileadi, E. Physical interpretation of the Warburg impedance. Corrosion 51, 664–671 (1995).

Herraiz-Cardona, I., Ortega, E., Vázquez-Gómez, L. & Pérez-Herranz, V. Double-template fabrication of three-dimensional porous nickel electrodes for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 37, 2147–2156 (2012).

Bastidas, D. M. Interpretation of impedance data for porous electrodes and diffusion processes. Corrosion 63, 515–521 (2007).

Montemor, M. F., Simoes, A. M. P. & Salta, M. M. Effect of fly ash on concrete reinforcement corrosion studied by EIS. Cement Concr. Compos. 22, 175–185 (2000).

Wildlng, C. R., Walter, A. & Double, D. D. A classification of inorganic and organic admixtures by conduction calorimetry. Cem. Concr. Res. 14, 185–194 (1984).

Machado, M. A. G. T. C. & Ribeiro, D. V. Inibidores de Corrosão em Concreto Armado contra oataque de agentes da chuva ácida. São Carlos, 161p. Tese (Doutorado), Universidade Federal de São Carlos, cited by J.C.C. Abrantes, Construction and Building Materials 111 (2016) 98–104. (2004).

Wu, K., Wang, Y. & Zhitomirsky, I. Electrophoretic deposition of TiO2 and composite TiO2-MnO2 films using benzoic acid and phenolic molecules as charging additives. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 352, 371 (2010).

Bryan Hirschorna, M. E., Orazema, B., Tribollet, V., Vivier, I. & Frateur Marco Musiani, determination of effective capacitance and film thickness from constant-phase-element parameters. Electrochim. Acta. 55, 6218–6227 (2010).

Kim, J. K., Kee, S. H., Futalan, C. M. & Yee, J. J. Corrosion Monitoring of Reinforced Steel Embedded in Cement Mortar under Wet-and-dry cycles by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Sensors 20, 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20010199 (2020).

Chakri, S. et al. Improved EIS analysis of the electrochemical behaviour of carbon steel in alkaline solution. Electrochim. Acta. 246, 924–930 (2017).

Ordan Baux, N. et al. Impedance analysis of film-forming amines for the corrosion protection of a carbon steel. Electrochim. Acta. 283, 699–70756 (2018).

Li, Y. Q. & Renyuan Studies on the electrode kinetics of polypyrrole in aqueous solution by a.c. Impedance Meas. Synth. Met. 64, 241–245 (1994).

Ghods, P., Isgor, O. B., Brown, J. R., Bensebaa, F. & Kingston, D. Appl. Surf. Sci. 257 : 4669. (2011).

Alhozaimy, A. A. N. A., Hussain, R. R., Al-Zaid, R., Singh, J. K. & Singh, D. D. N. Corrosion 70 74–8661. (2014).

Lv, S. & Li, K. Semiconducting Behaviour and Corrosion Resistance of Passive Film on Corrosion-Resistant Steel Rebars. Materials 15, 7644. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217644 (2022).

Ismail, M. A. and M. Ohtsu, monitoring corrosion rate of concrete by ac impedance spectroscopy, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242116707_Monitoring_corrosion_rate_of_concrete_by_AC_Impedance_Spectroscopy

Angyal, S. J. Complexes of metal cations with carbohydrates in solution. Advances in carbohydrate chemistry and biochemistry. Vol. 47. Academic Press, 1–43. (1989).

Peulon, S., Legrand, L., Antony, H. & Chausse, A. Electrochem. Commun. 5 20865. (2003).

Chung, K. W., Kim, K. B., Han, S. H. & Lee, H. Novel synthesis of Nanosized Cellular Iron Oxide/Oxyhydroxide Thin films I. Electrochemical synthesis of Green Rust Thin films and their chemical oxidation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, C560–C565 (2005).

Khoiroh, L. M., Khidin, F. & Ningsih, R. Synthesis of Maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles pigment from lathe waste by sonication – calcination method, IOP conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 456, 012005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/456/1/012005 (2020).

Li, Shengxi & Hihara, L. H. A Micro-raman Spectroscopic Study of Marine Atmospheric Corrosion of Carbon Steel: the Effect of Akaganeite. J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, C495–C502 (2015).

William, M. & Haynes CRC hand book of chemistry and physics (92nd ed.) CRC Press. ISBN 978-1439855119.

Makhotkina, O. & Kilmartin, P. A. The use of cyclic voltammetry for wine analysis: determination of polyphenols and free sulfur dioxide. Anal. Chim. Acta. 668 (2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2010.03.064 (2010). In medicinal plants.

Brown, J. E., Khodr, H., Hider, R. C. & Rice-Evans, C. A. Structural dependence of flavonoïd interactions with Cu2 + ions: implications for their antioxidant properties. Biochem. J. 330, 1173–1178 (1998).

Yoshioka, H., Ohashi, Y., Fukuda, H., Senba, Y. & Yoshioka, H. Spectral simulation of the ESR spectra of polyphenol radicals formed by reaction with hydroxyl radical. J. Phys. Chem. A. 107, 1127–1132 (2003).

Aldo Ponce, L. B. et al. Gaskell, and Bryan Eichhorn, Elucidation of the Fe (III) Gallate structure in historical Iron Gall Ink. Anal. Chem. 88 (2016).

Achal Pandya, J. K. & Singh, D. D. N. Singh, An eco-friendly method to stabilize unstable rusts,Proceedings of Metals 2016, New Delhi pp 136–147, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp021987p

Lothenbach, B. Thermodynamic equilibrium calculations in cementitious systems. Mater. Struct. 43, 1413–1433 (2010).

Hussain, R. R., Al-Negheimish, A., Alhozaimy, A. & Singh, D. D. N. Cem. Concr. Compos., 113103728. (2020).

Ivan Lucas, S., Durand-Vidal, E., Dubois, J., Chevalet, P. & Turq Surface charge density of Maghemite nanoparticles: role of Electrostatics in the Proton Exchange. J. Phys. Chem- istry C Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 18568 (2007).

Elakneswaran, Y. Electrokinetic potential of hydrated cement in relation to adsorption of chlorides. Cem. Concr. Res. 39, 340–344 (2009).

Thomas, N. L. & Double, D. The hydration of Portland cement, C3S and C2S in the presence of a calcium complexing admixture (EDTA. Cem. Concr Res. 13, 391–400 (1983).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Centre of Excellence for Concrete Research and Testing (CoE-CRT), College of Engineering, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions