Abstract

Vibrational resonance and chaos control in the canonical Chua’s circuit with a smooth cubic nonlinear resistor is investigated by an analog circuit experiment and a dynamical model. By adjusting the amplitude and frequency of the high-frequency signal while keeping other parameters constant, the system exhibits a resonant peak in its response to the weak low-frequency signal. Notably, when the amplitude of the high-frequency signal exceeds the critical threshold, the system undergoes a transition from a single-scroll chaotic attractor to a double-scroll chaotic attractor, marking the emergence of vibrational resonance. In particular, the maximum of the system’s response amplitude is insusceptible when the frequency of the high-frequency signal varies over a broad range, which indicates the strong robustness of the vibrational resonance in the present system. The experimental results are coincident with the numerical simulations. This research has potential applications in chaos control and weak signal detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, with the application and promotion of signal processing technology in different fields, the detection of weak signal in strong background noise has attracted considerable attention. Meanwhile, the rapid development of nonlinear science provides some new approaches for detecting weak signal, stochastic resonance (SR) is one of the most typical examples1. The concept of SR is proposed to address the mechanism of periodically recurrent ice ages2. With the continuous exploration of researchers, SR has been widely researched in physics3,4, biology5,6, and other fields7,8. Based on the principle of SR, researchers have employed noise with appropriate intensity into nonlinear systems to improve the system’s output and realize the detection of weak signals, such as in optical systems9 and excitable systems10.

Inspired by SR, researchers used the synergistic effect between high frequency signals, low frequency weak signals and system nonlinearity, and also realized the amplification and detection of weak signal by replacing noises with high frequency signals11. This effect has been called vibrational resonance (VR). Due to the signals of different time scales widely exist in various types of natural and artificial systems, such VR phenomena caused by two-frequency signals have gradually attracted the attention of researchers. Meanwhile, VR has been widely studied in nonlinear systems including position-dependent mass oscillator systems12, bistable systems13,14,15,16, periodic systems17,18,19, systems under entropic and energetic potentials20,21, and various Chua’s circuits22,23,24.

In all of the systems mentioned above, Chua’s circuit has been considered as one of the most simplest and widely investigated nonlinear circuits, which can produce rich nonlinear phenomena, such as chaos25,26,27 and bifurcation28,29,30,31. It is worth noting that among the family of Chua’s circuits, the canonical Chua’s circuit is important to investigate since the behaviors of each member can be realized in the canonical Chua’s circuit by simple adjustments32. Besides, the canonical Chua’s circuit contains the minimum number of circuit elements33,34. These remarkable characteristics mean that the investigation of VR in the canonical Chua’s circuit is universal and propagable. Additionally, in non-autonomous Chua’s circuit systems, researchers have investigated the mechanism for achieving voltage gain from Chua’s circuit using noise or periodic signals, for example, SR35,36, VR22,24,37, and coherence resonance38,39. In these reported studies, nonlinear resistors whose voltage-current curve is a linear piecewise functions are employed. Actually, the piecewise linear characteristic has advantages in terms of rigorous mathematical analysis40. However, the potential truncation error in the numerical simulations may be amplified due to the piecewise linear characteristic, and thus changing the resulting behavior. Furthermore, the characteristics of nonlinear devices are generally smooth in real circuits, not all features in real circuits can be captured correctly by the piecewise-linear function41,42. Therefore, it is of great practical significance to study VR in the Chua’s circuit equipped with a smooth nonlinear resistor.

Meanwhile, chaos control has received a lot of attention since its pioneering realization43,44,45,46. Classical chaos control can be achieved by altering system parameters or introducing small perturbations, enabling the system to change a chaotic solution into a periodic one or switch between multiple coexisting attractors43. Furthermore, the purpose phase-control techniques of chaos is to extract the periodic behavior of chaotic system by selecting a suitable phase of weak harmonic perturbation44,45,46, which is somewhat analogous to the VR. The presence of VR also relies on a biharmonic driving at two frequencies11,12,13,14, and there has been a small amount of work investigating the coexistence of vibrational resonance and chaos control47. Based on this commonality, we aim to establish a connection between vibrational resonance and the dynamical phase transition of chaotic attractors, and explore whether vibrational resonance can be used as an alternative method for the chaos control.

Due to the advantages of smooth characteristics in the study of nonlinear circuits, this type of the nonlinear resistors with smooth characteristics have been widely used in various types of nonlinear systems, for instance, dissipative Toda-Rayleigh systems48, fractional order Chua’s systems49, and active topological circuits50. Usama et al.23 have investigated the effect of VR in the original Chua’s circuit with smooth nonlinear characteristic by numerical simulations, but effects of the smoothness property on VR has not been investigated experimentally. Therefore, we will conduct the first experimental study of VR and chaos control in the canonical Chua’s circuit composed of a smooth nonlinear resistor.

The remainder part of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Proposed circuit” describes the system model and system circuit of this paper and investigates the volt-ampere characteristic curve of a smooth nonlinear resistor. The results are discussed in Section “Experimental and numerical results”. The whole paper is concluded in Section “Conclusion”.

Proposed circuit

Figure 1a shows the schematic diagram of the canonical Chua’s circuit driven by a biharmonic signal, which mainly includes an anti-phase adder (operational amplifier OA1 and linear resistors \(R_{1}\), \(R_{2}\), \(R_{3}\)), a smooth nonlinear resistor (NR), two linear resistors, two capacitors and one inductor. The circuit schematic of NR is shown in Fig. 1b, which includes five linear resistors, two analog multipliers and an operational amplifier OA2. The connections of the linear resistors \(R_{6}\), \(R_{7}\), \(R_{8}\) and the operational amplifier OA2 can equate the resistor \(R_{8}\) to a negative resistance when \(R_{6}=R_{7}\), thus obtaining the desired coefficients. The current (\(I_{\textrm{NR}}\))-voltage (\(U_{1}\)) equation reads: \({I_{\textrm{NR}}} = {{{\alpha ^2}({R_9} + {R_{10}})U_1^3} / {{R_8}{R_9}}} - {{{U_1}} / {{R_8}}} = aU_1^3 + bU_1\), where \(a = {{{\alpha ^2}({R_9} + {R_{10}})} / {{R_8}{R_9}}}\), \(b = - {1 / {{R_8}}}\), \(\alpha\) is the attenuation coefficient of the analog multiplier AD633 (\(\alpha = 0.1 \,{\hbox {V}^{ - 1}}\)).

(a) Schematic diagram of the canonical Chua’s circuit consisting with a smooth nonlinear resistor driven by a biharmonic signal. (b) Circuit schematic of the smooth nonlinear resistor. (c) The current-voltage characteristic curve of the nonlinear resistor. The solid line represents the experimental results and the dashed line represents the numerical results based on the current (\({I}_{\textrm{NR}}\))-voltage (\({U}_{{1}}\)) equation.

To make the NR present a smooth nonlinear characteristic under the experimental condition, the values of a, b are set as \(9.527 \times {10^{-6}} \, \hbox {S} /{\hbox {V}^{ 2}}\), \(-9.346 \times {10^{-4}} \, \textrm{S}\), respectively, and drive voltage range of \(-10 \,\hbox {V}\)–\(10 \,\hbox {V}\). The parameters (a) and (b) of the smooth nonlinear resistor are selected to ensure that the system achieves vibrational resonance when driven by a biharmonic signal22,23,24, while operating within the voltage ranges of the AD633 and LM741. Figure 1c shows that experimental results of the NR agree with numerical results based on the current-voltage equation, which indicates that the NR has a smooth characteristic.

Applying Kirchhoff’s laws, the circuit equations of Fig. 1a can be written as:

where \({{U_1}}\), \({{U_2}}\), \({{I_{\textrm{L}}}}\) represent the three state variables of the canonical Chua’s circuit. G(t) is a biharmonic signal with different frequencies

where signals \(B \cdot \sin (2\pi {\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}}t)\) and \(A \cdot \sin (2\pi {\omega _{\textrm{L}}}t)\) satisfy \({\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}} \gg {\omega _{\textrm{L}}}\).

Combining the engineering feasibility of the circuit and the parameter range which can realize the VR, the parameter are set as: \({R_1} = {R_2} = {R_3} = 10.0 \,\textrm{K} \Omega\), \({R_4} = 0.3 \,\hbox {K}\Omega\), \({R_5} = {R_6} = {R_7} = 2.0 \,\hbox {K}\Omega\), \({R_8} = 1.07 \,\hbox {K}\Omega\), \({R_9} = 51.6 \,\hbox {K}\Omega\), \({R_{10}} = 1.0 \,\hbox {K}\Omega\), \(L = \mathrm 15.0 \,\hbox {mH}\), \({C_{1}} = 10.0 \,\hbox {nF}\), \({C_{2}} = 100.0 \,\hbox {nF}\). The parameters of the resistor, inductor, and capacitor are set based on previous literature regarding vibrational resonance in Chua’s circuit22,23,24. In summary, the selection of these parameters is physically meaningful and takes into account the practical feasibility and rationality of the circuit experiment. The amplitude A and frequency \({\omega _L}\) of the low-frequency signal are fixed as \(0.7 \,\hbox {V}\) and \(50.0 \,\hbox {Hz}\), respectively. In addition, the experimental setup used in this study mainly includes the signal generator (UNI-T UTG6005B), the oscilloscope (RIGOL DS1074Z-S), and the three-way DC regulated power supply (DF1713SLL3A).

The research route of this study is shown in Fig. 2, which mainly involves building a system model firstly, then performing numerical simulation of the system model, and finally performing circuit experiments based on the numerical simulation results. The presentation form of the results of this study mainly includes the system output time series plot, the system phase diagram, the system response amplitude and the bifurcation diagrams.

Experimental and numerical results

Figure 3 shows time series \({U_1}(t)\) of the hardware circuit for different amplitudes B. As shown in Fig. 3a, when \(B = 0 \,\hbox {V}\), \({U_1}(t)\) is near the equilibrium points (the values of the equilibrium points are \(\pm \, 7.245 \,\hbox {V}\) when \(A=B = 0 \,\hbox {V}\). The experimental values are consistent with the numerical values based on Eqs. (1)–(3)). When \(B = 1.0 \,\hbox {V}\), as shown in Fig. 3b, due to the amplitude B is small, \({U_1}(t)\) cannot oscillate between the two equilibrium points, i.e., \(A \cdot \sin (2\pi {\omega _{\textrm{L}}}t)\) has not been amplified. When \(B = 4.0 \,\hbox {V}\), as shown in Fig. 3c, it is clearly seen that \({U_1}(t)\) vibrates periodically between the two equilibrium points, and the system’s output is synchronized with \(A \cdot \sin (2\pi {\omega _{\textrm{L}}}t)\). Under this condition, \(A \cdot \sin (2\pi {\omega _{\textrm{L}}}t)\) is amplified significantly. When \(B = 9.0 \,\hbox {V}\), as shown in Fig. 3d, \({U_1}(t)\) will switch rapidly between the two equilibrium points and completely submerge the low-frequency signal.

Time series of the system’s output \({U_1}(t)\) for different amplitudes B of the high-frequency signal. Sine curves represent the input weak low-frequency signal (its amplitude is amplified 10 times). Other parameters: \(A = 0.7 \,\textrm{V}\), \({\omega _{\textrm{L}}} = 50.0 \,\textrm{Hz}\), \({\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}} = 2000.0 \,\textrm{Hz}\). (a) \(B = 0 \,\textrm{V}\), (b) \(B = 1.0 \,\textrm{V}\), (c) \(B = 4.0 \,\textrm{V}\), (d) \(B = 9.0 \,\textrm{V}\).

To characterize this VR effect quantitatively, the fast Fourier transform has been applied to analysis the output signal \({U_1}(t)\), and the amplitude of the output signal at the frequency \({\omega _{\textrm{L}}}\) of the low-frequency signal is obtained as the response amplitude Q11,14. In addition, to confirm the correctness of the experimental results, the numerical simulations based on Eqs. (1)–(3) have been carried by the fourth-order Runge-Kutta algorithm, where the time step is \(1.0 \times {10^{-7}}\). To better capture the system’s tendency to oscillate near the equilibrium points (with values of \(\pm \, 7.245 \,\hbox {V}\)) in the absence of external driving, the initial conditions in the numerical simulations are set close to these points.

The response amplitude Q varies with the amplitude B. The inset shows the phase diagram of \({U_2} - {U_1},\) from bottom to top, \(B = 3.25 \,\textrm{V},\) \(3.375 \,\textrm{V}.\) Other parameters: \(A = 0.7 \,\textrm{V},\) \({\omega _{\textrm{L}}} = 50.0 \,\textrm{Hz},\) \({\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}} = 2000.0 \,\textrm{Hz}.\) The experiment results are obtained by the system’s output \({U_1}(t)\) of Fig. 1a, and the numerical results are obtained by the numerical simulations based on Eqs. (1)–(3).

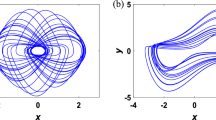

Figure 4 presents the response amplitude Q varies with the amplitude B. As the amplitude B increases, the Q first increases slowly, then sharply increases, showing a wide peak, and finally rapidly decreases first and then slowly decreases. There is a critical value of B (the critical value equals \(3.375 \,\hbox {V}\)) for the occurrence of VR. A quantitative agreement between experimental and numerical results is observed. To demonstrate the dynamical phase transition of the system, the phase diagram of the system has been obtained by numerical simulations. As shown in the inset of Fig. 4, an interesting phenomenon can be observed based on the mechanism of VR: the system will change from a single-scroll attractor to a double-scroll attractor when the response amplitude Q increases sharply. This indicates that the change of the high-frequency signal not only can achieve VR, but also can control the chaotic state of this system. When the amplitude and frequency of the low-frequency signal are fixed, the mechanism by which varying the amplitude of the high-frequency signal induces vibrational resonance is that the high-frequency signal alters the system’s effective potential function, thereby causing the system to oscillate at the frequency of the weak low-frequency signal.

The response amplitude Q varies with the frequency \({\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}}\) of the high-frequency signal. The inset shows the phase diagram of \({U_2} - {U_1}\), from bottom to top, \(\Omega = 3075 \,\textrm{Hz}\), \(3325 \,\textrm{Hz}\). Other parameters: \(A = 0.7 \,\textrm{V}\), \({\omega _{\textrm{L}}} = 50.0 \,\textrm{Hz}\), \(B = 4.0 \,\textrm{V}\). Symbols mean the same as in Fig. 3.

Considering that the high-frequency signal is an indispensable element to change the stiffness of the system, Fig. 5 shows the variation of the response amplitude Q with the frequency \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\). The response amplitude Q shows a broad resonance peak as the frequency \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\) increases. The broad peak ends with a sharp drop in Q. There is a critical value of \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\) (the critical value equals \(3.375 \,\hbox {V}\)) for the occurrence of VR. The behavior of VR is consistent between experimental results and numerical simulations, while the curve of experimental results is shifted towards to left slightly compared to the theoretical results. The cause for this slight deviation is that the capacitors and the inductor have a tolerance of \(10\%\). Use the same approach as Fig. 4, the phase diagram of the system has been obtained by numerical simulations. As shown in the inset of Fig. 5, an interesting phenomenon can be observed based on the mechanism of VR: the chaotic attractor changes from a double-scroll state to a single-scroll state when the driving frequency \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\) decreases abruptly. This indicates that changing frequency of the high-frequency signal not only can achieve VR, but also can control the chaotic state. The underlying mechanism behind this phenomenon is that different high-frequency signal frequencies modify the structure of the effective potential function, thereby influencing the chaotic state of the system.

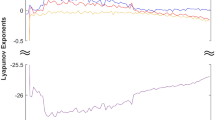

In order to further quantitatively analyze the relationship between the vibrational resonance and chaos control, bifurcation diagrams corresponding to Figs. 4 and 5 are obtained, which are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. As shown in Fig. 6, the system gradually changes from a single-scroll chaotic attractor state (\(B=3.25 \,\textrm{V}\)) to a double-scroll attractors state (\(B = 3.375 \,\textrm{V}\)) as the amplitude B of the high-frequency signal increases. In contrast, when the frequency \({\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}}\) of the high-frequency signal is increased, the system undergoes the transition from a two-scroll chaotic attractors state (\({\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}} = 3075.0 \,\textrm{Hz}\)) to a single-scroll chaotic attractor state (\({\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}} = 3325.0 \,\textrm{Hz}\)), as shown in Fig. 7. It is worth noting that the dynamical transition behavior between the two kinds of chaotic states changes during the increase in B and \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\). In all, the results of bifurcation diagrams in Figs. 6 and 7 are in good agreement with transition points of vibrational resonance and phase diagrams in Figs. 4 and 5. Therefore, by adjusting B and \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\), not only the VR can be realized, but also the chaotic state of the system can be effectively controlled.

For a more comprehensive exploration of the effect of \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\) on VR, the contour plot of the response amplitude Q with the amplitude B and the frequency \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\) is shown in Fig. 8. Despite the experimental components have the unavoidable loss, Fig. 8a (experiment results) still shows an agreement with Fig. 8b (numerical simulation results). One can see that as the frequency \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\) increases, the optimized amplitude B required for VR also increases. This indicates a close dependency relationship between the critical value \({B_{\textrm{V}R}}\) and the frequency \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\). This phenomenon has also been observed in other nonlinear systems22,51,52. The physical mechanism for this dependence is as follows. The oscillation frequency of the oscillator in a single potential well increases with \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\) increases, then the energy required by the particle switching between the potential wells also increases, while the energy is mainly provided by the high-frequency signal.

Contour plot of the response amplitude Q varies with the amplitude B and the frequency \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\). Different colors denote different Q. (a) Experimental results, B and \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\) change with steps \(0.2 \,\textrm{V}\) and \(150.0 \,\textrm{Hz}\), respectively, (b) numerical simulation results, B and \(\varOmega _{\textrm{H}}\) change with steps \(0.125 \,\textrm{V}\) and \(120.0 \,\textrm{Hz}\), respectively. Other parameters: \(A = 0.7 \,\textrm{V}\), \({\omega _{\textrm{L}}} = 50.0 \,\textrm{Hz}\).

Combining Figs. 5 and 8, and comparing the experimental results of VR in other nonlinear systems including the classical Chua’s circuit with a piecewise-linear nonlinear resistor (see Fig. 5b in Ref. 22) and the bistable system (see Fig. 4 in Ref. 14), it can be concluded that the canonical Chua’s circuit composed with a smooth nonlinear resistor can achieve VR in a larger range of the frequency of the high-frequency signal. It is worth noticing that the peak value of the response amplitude remains a constant value. This strong robustness property is beneficial to the popularization and application of VR in the engineering field. In addition, the strong robustness exhibited by the present circuit enables this research to be more applicable to applications in potential fields such as weak signal detection, mechanical engineering and communication technology.

Conclusion

For the first time, the vibrational resonance in the canonical Chua’s circuit composed with a smooth nonlinear resistor has been investigated by the analog circuit experiment and the corresponding dynamical model. Experimental and numerical results show that the vibrational resonance exists with changing the amplitude and the frequency of the high-frequency signal. It is found that the chaotic attractor can be controlled between the single-scroll and the double-scroll by tuning the high-frequency signal, which can provide new insights into the chaos control. In addition, both the frequency and amplitude of the high-frequency signal can produce the vibrational resonances over a wide range of parameters. Based on the fact that the canonical Chua’s circuit can realize the behavior of each member of the Chua’s circuit family, this research not merely enriches the experimental investigation of vibrational resonance, but also provides a universal model for the vibrational resonance and chaos control in the Chua’s circuit family.

Data availability

Data will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gammaitoni, L., Hänggi, P., Jung, P. & Marchesoni, F. Stochastic resonance. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 223–287 (1998).

Benzi, R., Parisi, G., Sutera, A. & Vulpiani, A. Stochastic resonance in climatic change. Tellus 34, 10–16 (1982).

Sawkmie, I. S. & Mahato, M. C. Stochastic resonance and free oscillation in a sinusoidal potentials driven by a square-wave periodic force. Eur. Phys. J. B 94, 44 (2021).

Zhu, Q., Zhou, Y., Marchesoni, F. & Zhang, H. P. Colloidal stochastic resonance in confined geometries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 098001 (2022).

Wiesenfeld, K. & Moss, F. Stochastic resonance and the benefits of noise: From ice ages to crayfish and squids. Nature 373, 33–36 (1995).

Benzi, R. Stochastic resonance: From climate to biology. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 17, 431–441 (2010).

Yang, H. M. & Yao, Y. G. Logical stochastic resonance in the Hodgkin-Huxley neuron. Pramana-J. Phys. 97, 80 (2023).

Lu, S. L., He, Q. B. & Wang, J. A review of stochastic resonance in rotating machine fault detection. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 116, 230–260 (2019).

McNamara, B., Wiesenfeld, K. & Roy, R. Observation of stochastic resonance in a ring laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2626–2629 (1988).

Lindner, B., García-Ojalvo, J., Neiman, A. & Schimansky-Geier, L. Effects of noise in excitable systems. Phys. Rep. 392, 321–424 (2004).

Landa, P. S. & McClintock, P. V. E. Vibrational Resonance. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 33, L433–L488 (2000).

Roy-Layinde, T. O., Omoteso, K. A., Oyero, B. A., Laoye, J. A. & Vincent, U. E. Vibrational resonance of ammonia molecule with doubly singular position-dependent mass. Eur. Phys. J. B 95, 80 (2022).

Jeevarathinam, C., Rajasekar, S. & Sanjuán, M. A. F. Theory and numerics of vibrational resonance in Duffing oscillators with time-delayed feedback. Phys. Rev. E 83, 066205 (2011).

Baltanas, J. P. et al. Experimental evidence, numerics, and theory of vibrational resonance in bistable systems. Phys. Rev. E 67, 066119 (2003).

Liu, J. L., Jiang, J. H., Ge, M. M., Li, Y. Y. & Du, L. C. An analog circuit experiment on vibrational resonance of an underdamped bistable system. J. Eng. 2022, 857–861 (2022).

Liu, J. L., Li, C. R., Gao, H. L. & Du, L. C. Vibrational resonance in globally coupled bistable systems under the noise background. Chin. Phys. B 32, 070502 (2023).

Vincent, U. E., Roy-Layinde, T. O., Popoola, O. O., Adesina, P. O. & McClintock, P. V. E. Vibrational resonance in an oscillator with an asymmetrical deformable potential. Phys. Rev. E 98, 062203 (2018).

Du, L. C., Song, W. H., Guo, W. & Mei, D. C. Multiple current reversals and giant vibrational resonance in a high-frequency modulated periodic device. EPL 115, 40008 (2016).

Samikkannu, R., Ramasamy, M., Kumarasamy, S. & Rajagopal, K. Studies on ghost-vibrational resonance in a periodically driven anharmonic oscillator. Eur. Phys. J. B 96, 56 (2023).

Du, L. C., Han, R. S., Jiang, J. H. & Guo, W. Entropic vibrational resonance. Phys. Rev. E 102, 012149 (2020).

Jiang, J. H., Li, K. Y., Guo, W. & Du, L. C. Energetic and entropic vibrational resonance. Chaos Soliton Fract. 152, 111400 (2021).

Jothimurugan, R., Thamilmaran, K., Rajasekar, S. & Sanjuán, M. A. F. Experimental Evidence for vibrational resonance and Enhanced signal Transmission in Chua’s Circuit. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 23, 1350189 (2013).

Usama, B. I., Morfu, S. & Marquie, P. Vibrational resonance and ghost-vibrational resonance occurrence in Chua’s circuit models with specific nonlinearities. Chaos Soliton Fract. 153, 111515 (2021).

Abirami, K., Rajasekar, S. & Sanjuán, M. A. F. Vibrational and ghost-vibrational resonances in a modified Chua’s circuit model equation. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 24, 1430031 (2014).

Hartley, T. T., Lorenzo, C. F. & Qammer, H. K. Chaos in a fractional order Chua’s system. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fundam. Theory Appl. 42, 485–490 (1995).

Yu, H. F., Shen, Z. N., Zhang, Y. Y., Huang, S. Cai. & Du, S. C. A new multi-scroll Chua’s circuit with composite hyperbolic tangent-cubic nonlinearity: Complex dynamics, hardware implementation and image encryption application. Integration 81, 71 (2021).

Volos, C. Dynamical analysis of a memristive Chua’s oscillator circuit. Electronics 12, 4734 (2023).

Wang, Z. X., Zhang, C. & Bi, Q. S. Bursting oscillations with bifurcations of chaotic attractors in a modified Chua’s circuit. Chaos Soliton Fract. 165, 112788 (2022).

Kennedy, M. P. Three steps to chaos. II. A Chua’s circuit primer. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fundam. Theory Appl. 40, 657 (1993).

Wang, Z. X., Zhang, C., Zhang, Z. D. & Bi, Q. S. Bursting oscillations with boundary homoclinic bifurcations in a Filippov-type Chua’s circuit. Pramana-J. Phys. 94, 95 (2020).

Luo, H. B. et al. Reconstructing bifurcation diagrams of chaotic circuits with reservoir computing. Phys. Rev. E 109, 024210 (2024).

Wu, S. X. Chua’s circuit family. Proc. IEEE 75, 1022 (1987).

Chua, L. O. & Lin, G. N. Canonical realization of Chua’s circuit family. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 37, 885 (1990).

Kyprianidis, I. M., Petrani, M. L., Kalomiros, J. A. & Anagnostopoulos, A. N. Crisis-induced intermittency in a third-order electrical circuit. Phys. Rev. E 52, 2268–2273 (1995).

Silva, I. G., Korneta, W., Stavrinides, S. G., Picos, R. & Chua, L. O. Observation of stochastic resonance for weak periodic magnetic field signal using a chaotic system. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 94, 105558 (2021).

Anishchenko, V. S., Safonova, M. A. & Chua, L. O. Stochastic resonance in Chua’s circuit. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2, 397 (1992).

Ashokkumar, P., Abilan, R., Aravindh Venkatesan, M. S. A. & Lakshmanan, M. Harnessing vibrational resonance to identify and enhance input signals. Chaos 34, 013129 (2024).

Zhu, L. Q., Lai, Y. C., Liu, Z. H. & Raghu, A. Can noise make nonbursting chaotic systems more regular. Phys. Rev. E 66, 015204 (2002).

Arathi, S., Rajasekar, S. & Kurths, J. Stochastic and coherence resonances in a modified Chua’s circuit system with multiscroll orbits. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 23, 1350132 (2013).

Rocha, R. & Medrano, R. O. Stability analysis for the Chua’s circuit with cubic polynomial nonlinearity based on root locus technique and describing function method. Nonlinear Dyn. 102, 2859–2874 (2020).

Fozin, T. F. et al. On the dynamics of a simplified canonical Chua’s oscillator with smooth hyperbolic sine nonlinearity: Hyperchaos, multistability and multistability control. Chaos 29, 113105 (2019).

Khibnik, A. I., Roose, D. & Chua, L. O. On periodic orbits and homoclinic bifurcations in Chua’s circuit with a smooth nonlinearity. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 3, 363 (1993).

Ott, E., Grebogi, C. & Yorke, J. A. Controlling Chaos. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 1196–1199 (1990).

Meucci, R. et al. Optimal phase-control strategy for damped-driven duffing oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 044101 (2016).

Zambrano, S. et al. Numerical and experimental exploration of phase control of chaos. Chaos 16, 013111 (2006).

Meucci, R., Ginoux, J. M., Mehrabbeik, M., Jafari, S. & Sprott, J. C. Generalized multistability and its control in a laser. Chaos 32, 083111 (2022).

Monwanou, A. V. et al. Nonlinear dynamics in a chemical reaction under an amplitude-modulated excitation: Hysteresis, vibrational resonance, multistability, and chaos. Complexity 2020, 8823458 (2020).

del Makarov, V. A., Rio, E., Ebeling, W. & Velarde, M. G. Dissipative Toda-Rayleigh lattice and its oscillatory modes. Phys. Rev. E 64, 036601 (2001).

Odibat, Z., Corson, N., Aziz-Alaoui, M. A. & Alsaedi, A. Chaos in fractional order cubic Chua system and synchronization. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 27, 1750161 (2017).

Kotwal, T. et al. Active topolectrical circuits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2106411118 (2021).

Deng, B., Wang, J., Wei, X. L., Yu, H. T. & Li, H. Y. Theoretical analysis of vibrational resonance in a neuron model near a bifurcation point. Phys. Rev. E 89, 062916 (2014).

Ghosh, S. & Ray, D. S. Nonlinear vibrational resonance. Phys. Rev. E 88, 042904 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Yunnan Province Applied Basic Research Project (Grant No. 202401AT070422) and the Xingdian Talents Support Project, China. The authors would like to thank Dr. Wei Guo and Mr. Chao Wang for their insightful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.D. designed the whole project. H. L. completed the experiment and prepared figures in the draft. All authors wrote the main manuscript text. C.L. and L.D. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. In all, H.L., J.L. and C.L. contributed equally to the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Liu, J., Li, C. et al. Vibrational resonance and chaos control in the canonical Chua’s circuit with a smooth nonlinear resistor. Sci Rep 14, 31013 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82250-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82250-9