Abstract

We report a controlled deposition process using atmospheric plasma to fabricate silver nanoparticle (AgNP) structures on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrates, essential for stretchable electronic circuits in wearable devices. This technique ensures precise printing of conductive structures using nanoparticles as precursors, while the relationship between crystallinity and plasma treatment is established through X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The XRD studies provide insights into the effects of plasma parameters on the structural integrity and adhesion of AgNP patterns, enhancing our understanding of substrate stretchability and bendability. Our findings indicate that atmospheric plasma-aided printing not only avoids the need for high-temperature sintering but also significantly enhances the electrical and mechanical properties of the conductive structures, advancing the production of robust and adaptable electronic devices for wearable technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The integration of metal and metal oxide microstructures on flexible substrates such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) presents a frontier in the development of advanced electronic devices1,2,3,4,5,6,7. PDMS, a widely used silicone-based organic polymer, offers unique advantages due to its flexibility, optical transparency, biocompatibility, and thermal stability8,9,10,11,12. These properties make PDMS an ideal candidate for applications ranging from microfluidics13,14,15,16, stretchable electronics16,17,18,19,20, and soft actuators21,22,23,24,25,26 to wearable electronics27,28,29,30,31. PDMS stands out for its exceptional mechanical flexibility, characterized by a low Young’s modulus (E ∼ 1–3 MPa), which enables devices to bend, stretch, and conform to various shapes31,32. This flexibility, combined with its optical clarity (transparent from 240 to 1100 nm), low thermal degradation threshold (> 400 °C), and biocompatibility, underscores its significance in the development of flexible and stretchable electronic devices31. However, the hydrophobic nature and low surface tension of PDMS make it challenging to deposit conductive layers.

The fabrication considerations in printed electronics, including pre-and post-printing treatments, are crucial for optimizing performance and achieving reliable device functionality. Substrate cleaning, surface modification, and ink optimization play a vital role in enhancing printability and adhesion33. Pre-treatment processes such as plasma cleaning and UV irradiation can improve the wettability and surface energy of substrates, facilitating better bonding of conductive inks. Effective post-printing treatments, including low-temperature curing or sintering, are also essential for enhancing conductivity without compromising the flexibility of the substrate33.

However, the inherent hydrophobicity and low surface energy of PDMS pose significant challenges for the direct deposition of metal or metal oxide structures using conventional vacuum-based deposition techniques such as sputtering, thermal evaporation, and atomic layer deposition (ALD)10,11,34,35. While techniques like aerosol jet printing and microcontact printing have been effective in addressing adhesion and conductivity challenges for flexible electronics11,36, they often require prolonged post-sintering or a coating of PDMS over the conductive structures, making the process more time-consuming and labor-intensive. Integrating plasma as a post-treatment for conductive patterns, instead of high-temperature sintering, offers a promising solution by enabling the deposition of conductive materials on PDMS with improved adhesion and mechanical integrity10,37,38,39. This approach leverages plasma to modify the surface properties of PDMS temporarily, allowing for the precise patterning of metal nanoparticles and enhancing device performance without compromising the substrate’s elasticity9,37,38,40.

The advent of plasma-aided printing technology has marked a significant milestone in the field of nanoparticle deposition, offering a streamlined and efficient approach to material fabrication41,42,43,44,45. This technique, which propels a mist of nanoparticles through a high-voltage field to generate plasma, has been recognized for its broad applicability across various materials and substrates46,47,48,49,50,51,52. Despite its advantages, the method’s precision and reproducibility have raised concerns, primarily due to the lack of sophisticated printing setups and comprehensive benchmarking studies. These challenges underscore the need for rigorous evaluation to optimize the process for diverse applications53. Plasma printing demonstrates broad applicability by effectively depositing a wide range of materials, including metals like silver (Ag), copper (Cu), and gold (Au), as well as semiconductors and oxides such as titanium dioxide (TiO2), tin oxide (SnO2), copper oxide (CuO), and zinc oxide (ZnO)54. These materials have been successfully printed on various substrates, including paper, cotton, glass, silicon, polyimide, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and printed circuit boards (PCBs)48,55. Comparative studies49 have demonstrated significant enhancements in material properties under plasma-on conditions. For instance, the plasma printing of carbon nanotubes revealed improvements in nanotube density, interconnectivity, and conductance, achieving conductance levels three orders of magnitude higher than those obtained without plasma. Similar advancements have been noted in the plasma printing of silver and graphene, where the use of plasma resulted in higher conductance without the need for additional sintering steps41,48,55.

The hydrophobic nature of PDMS presents challenges for the direct deposition of metallic or nanoparticle conductive materials using traditional inkjet printing or vacuum-based deposition techniques56. This paper seeks to address these challenges by benchmarking plasma parameters for effectively printing silver nanoparticles on PDMS substrates (Fig. 1a, b). This study extensively examines plasma conditions, including voltage and post-plasma treatment effects, exploring the interplay between PDMS surface properties and plasma characteristics (Fig. 1c). The relationship between crystallinity and plasma treatment is established through X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, alongside evaluations of the substrate’s stretchability and bendability, providing insights into the potential of plasma-aided printing for creating conductive structures on flexible substrates (Fig. 1b). Therefore, plasma-aided printing emerges as a promising avenue for depositing wide range of materials on various flexible substrates. While its simplicity is appealing, the method’s accuracy and reproducibility necessitate further investigation and benchmarking, particularly for PDMS substrates. By addressing these challenges, this investigation aims to enhance the understanding of plasma printing dynamics and optimize the process for broader applications in flexible electronics.

(a) Plasma-aided inkjet printing of conductive structures on PDMS substrate using silver nanoparticle (AgNP) ink, (b) Impact of bending and stretching on a PDMS-based stretchable electronic circuit created through plasma printing with AgNP ink, (c) Plasma plume size and temperature of the printhead ceramic tube (using FLIR images) corresponds to different plasma voltage.

Materials, fabrication, and testing

Materials used

PDMS substrate (2 mm thick) is fabricated using a polymer-to-hardener ratio of 1 to 10. The silver nanoparticle (AgNP) ink is achieved by precisely blending DI water with commercially sourced AgNP ink from NovaCentrix (JS-A191 Silver Nanoparticle Ink, 40% w/w Ag, Aqueous- High conductivity). An optimized ink-to-water ratio of 1 to 7 is determined to yield superior misting rates, a parameter consistently employed during the entirety of the printing process.

Plasma printing method

Using an atmospheric plasma-aided inkjet printer developed by Space Foundry Inc., we printed conductive patterns onto a 2 mm thick PDMS substrate. The printing process involved the generation of a low-temperature atmospheric plasma through a mix of inert gases (comprising 95% argon and 5% hydrogen). This mixing of silver ink aerosol and argon plasma enabled the effective deposition of conductive patterns on the PDMS surface. The printing quality was influenced by several factors, such as the percentage of ink aerosol, plasma voltage and frequency in the high voltage generator, the speed of printing, the number of printing and post plasma treatment passes, the distance between the printhead nozzle and the substrate, and the flow rates of both the aerosol (wet gas) and the inert gas (dry gas).

In our study, we mainly focused on the effect of plasma voltage and the number of printing and inert plasma post-treatment on the quality of the printed conductive structures and its adhesion to the substrate. Five distinct samples were developed and characterized with different plasma voltages to study the impact of plasma voltage on the fabricated conductive patterns. We chose 11 kV, 14 kV, 17 kV, 20 kV, and 23 kV peak-to-peak at 30 kHz frequency as the plasma voltage for this experiment. The following printing parameters are kept constant for developing the above five samples. The print speed was set to 0.5 mm/s for both printing and post-treatment. The mist level was set at 45%. The printhead was positioned 6 mm above the substrate, and a gas ratio of 100/400 SCCM (wet gas to dry gas flow rate) was implemented. The conductive structure was fabricated with two prints and two inert plasma treatment passes (sandwiching of printing and post-treatment) for all five samples. The inert plasma treatment was conducted under conditions similar to the printing process, with the same plasma settings, but without feeding the ink.

Further, we studied the effect of multiple printing and post-treatment on the adhesion and conductivity of the fabricated structures. For this, we developed seven distinct samples named S1 to S7 with different numbers of printing and post-treatment (Table 1). All the remaining printing parameters were kept constant throughout the process. The print speed was set to 0.5 mm/s for both printing and post-treatment. The mist level was set at 45%, and the voltage was calibrated to 17 kV peak to peak at 30 kHz frequency. The printhead was positioned 6 mm above the substrate, and a gas ratio of 100/400 SCCM (wet gas to dry gas flow rate) was implemented.

Surface morphology, chemical composition, crystalline analysis, and bending performance evaluation

The surface morphology of the conductive structure developed through plasma printing of AgNPs was analyzed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FeSEM) coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Additionally, a 3D optical profiler was employed to obtain comprehensive insights into both surface topography and chemical composition. The crystallinity of the AgNPs was assessed using X-ray diffractometry (XRD), analyzing peak intensities within the 20° to 80° 2θ scanning range. Furthermore, the resistance of samples S2 to S7 was measured during stretching using custom-made dynamic resistance measuring equipment.

Results and discussion

PDMS samples were placed on the plasma printer platform. The plasma settings were adjusted according to the parameters outlined in Table 2. We examined the impact of plasma treatment on the plasma-aided printing of silver nanoparticles on PDMS. We observed that by altering the plasma voltage (11–23 kV) and the number of plasma coatings applied resulted in significant changes in the quality and properties of the printed structures (S1-S7).

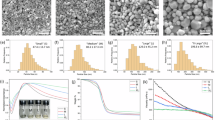

The primary factor in plasma-aided printing is the peak-to-peak voltage (kilovolts), which significantly influences various aspects of printing. This includes the crystallinity of the printed structures and their morphological and electrical properties, particularly under conditions of high stress, such as extensive stretching and bending. SEM analysis of printed microstructures showcased distinct nanostructural features attributable to plasma-aided printing (Figure S1a-e). At lower voltages, we observed surfaces characterized by smaller nanoparticles, resulting in a smooth appearance under SEM (JSM-6060) at lower magnifications, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. Interestingly, at 4000 times magnifications, no discrete particles were discernible. Beyond 17 kV, an increase in surface roughness was noted, a change attributed to the deposition of larger nanoparticles (Fig. 2b, c). With higher kilovolt settings, notably at 20 kV, the formation of more continuous films was evident, with the nanoparticles being particularly small in size (Fig. 2d-f). As the plasma voltage increased, microstructures that were predominantly spherical caps began to exhibit additional features, resembling clusters of spheres, contributing to a more complex surface topology. This transformation was accompanied by the development of a highly porous structure, indicating that the enhanced spherical forms not only clustered but were also porous in nature, adding a unique characteristic to the nanostructured surface (Figure S2a-e).

SEM images of AgNP conductive structures (two times single print with plasma and immediate post-inert plasma treatment after each print) on PDMS printed with a plasma voltage of (a) 11 kV, (b) 14 kV, (c) 17 kV, (d) 20 kV, (e) 23 kV, (f) Plot of average AgNP size in Ag conductive structures for samples printed with a plasma voltage from 11 to 23 kV.

At 11 kV, nanostructures were barely discernible, with only very small structures visible even under high-resolution SEM. An additional application of bare plasma coating at this voltage level resulted in the formation of larger nanostructures. At 11 kV, the coating was smooth, and the particle size was difficult to measure (Fig. 2a). However, as the plasma voltage increased to the range of 14 to 17 kV, the particle size expanded to between 298.4 and 574.4 nm (Fig. 2b, c). Further elevation of the voltage to 20 to 23 kV led to a decrease in particle size (Fig. 2d, e), with measurements ranging from 544.9 to 508.9 nm (Fig. 2f), indicating a notable variation in nanoparticle size and structure with voltage increments (Table 3). This variation underscores the capacity to control the deposited nanoparticle sizes on the substrate by adjusting the plasma voltage despite using the same source of silver nanoparticle ink. Therefore, subsequent research will focus on creating structures with varying porosities, which can be precisely controlled through adjustments in plasma settings.

Adhesion and morphological characteristics

In the examination of silver nanoparticles adhesion to PDMS substrates, as depicted in Fig. 3a-e (cross-sectional side view) (Figure S3a-e), a notably uniform layer of silver nanoparticles was observed at lower plasma voltages with a layer thickness of 5.2 μm corresponds to 11 kV plasma voltage (Fig. 3a) and 3.8 μm for 14 kV (Fig. 3b), though adhesion to PDMS was minimal. At 17 kV, the conductive structures exhibit good adhesion to the PDMS with a layer thickness of 4.99 μm (Fig. 3c). At elevated voltages, such as 20 and 23 kV, the PDMS substrate showed signs of cracking, and the alignment of silver particles became scattered and non-uniform. The layer thickness was measured to be 3.07 μm at 20 kV (Fig. 3d) and 3.47 μm at 23 kV (Fig. 3e). It was observed that at these higher voltages, nanoparticles penetrated the PDMS, yet the subsequent layer-by-layer nanoparticle bombardment compromised the underlying layer’s integrity (Figure S4a-e). This effect was particularly pronounced at the highest plasma voltages, where the initial layer was either destroyed or its structure was deformed due to the impact from subsequent nanoparticle coatings applied via plasma (Fig. 3f).

Cross-sectional SEM images of AgNP conductive structures (two times single print with plasma and immediate post-inert plasma treatment after each print) on PDMS printed with a plasma voltage of (a) 11 kV, (b) 14 kV, (c) 17 kV, (d) 20 kV, (e) 23 kV, (f) Plot of average print thickness of Ag conductive structure on PDMS for samples printed with a plasma voltage from 11 to 23 kV.

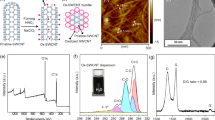

Figure 4 illustrates the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of AgNP conductive structures on PDMS, subjected to two consecutive single prints with plasma and immediate post-inert plasma treatment after each print. These structures were printed with varying plasma voltages: 0 kV, 11 kV, 14 kV, 17 kV, and 20 kV, aiming to assess particle quality and crystalline characteristics. Notably, the absence of additional peaks related to impurities in the spectra indicates the purity of the plasma-printed silver cubic phase (space group Fm-3 m, JCPDS card No. 87–0597). The XRD analysis highlights strong diffraction peaks at the (111) plane for AgNPs, observed at 37.08° (0 kV), 37.09° (11 kV), 37.09° (14 kV), 37.08° (17 kV), and 37.11° (20 kV) angle. Utilizing the Scherrer formula, the XRD data facilitated the calculation of the crystallite diameter (D) of Ag nanoparticles, revealing a range from approximately 10.65 nm to 24.60 nm.

Here FWHM is the full width at half maximum of the respective peak in radian, and θ represents the diffraction peak angle. K is the Scherrer constant, which is dependent on the crystallite shape and can be considered as 0.9 57; λ is the X-ray wavelength of the incident Cu Kα radiation, which is 0.154056 nm58. The calculated crystalline sizes and material percentages for all the samples are presented in Table 4.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of plasma printed AgNP conductive structures on PDMS. Each structure underwent two successive single prints with plasma treatment, followed by immediate post-inert plasma treatment after each print. The patterns are presented for different plasma voltages (0, 11, 14, 17, and 20 kV).

Across the examined range from 0 kV to 20 kV, there is a consistent increase in crystallinity, evidenced by escalating average areas of crystalline peaks and higher percentages of crystallinity (Table 4). Specifically, at 0 kV, the material exhibits a crystallinity of 10.65%, which steadily rises to 24.60% at 20 kV. This observed trend underscores the influence of plasma voltage on the crystalline nature and quality of the printed structures. Higher plasma voltages result in enhanced crystallinity, indicating improved structural order and potentially superior functional properties. These findings provide valuable insights for optimizing the fabrication process of AgNP-based conductive structures and hold promise for their application in various electronic and biomedical fields.

The thickness measurements from the SEM images show that beyond a certain point, the thickness does not increase with higher plasma voltage. This is attributed to material dispersion caused by the greater plasma bombardment at elevated voltages (Fig. 3f). Consequently, a plasma voltage of 17 kV was identified as optimal for achieving uniform, porous structures that adhere well to the PDMS substrate (Fig. 5a, b) and was thus selected for all experiments. The EDS elemental composition analysis was conducted to confirm the presence of silver (Ag) in the conductive structure. Two points were selected for this analysis: Point P1 on the conductive printed structure and Point P2 on the PDMS substrate (Fig. 5c). The EDS analysis at Point P1 revealed a compound percentage of 76.37% Ag with no detectable presence of silicon (Si) from the PDMS. At Point P2, no Ag was detected; only Si was present, with a percentage of 39.39% (Fig. 5d).

(a) SEM images of AgNP conductive structures (two times single print with plasma and immediate post-inert plasma treatment after each print) on PDMS printed with 17 kV plasma voltage, (b) High-resolution SEM image showing porous AgNP, (c) Print layer thickness indicated with cross-sectional SEM image, (d) EDS elemental composition of Ag conductive structure on PDMS.

Impact of layered printing and successive plasma treatments on PDMS conductive structures

The surface morphology and cross-sectional characteristics of the samples were analyzed to assess the influence of multiple plasma treatments on PDMS. Sample S1, which was printed on PDMS with a single pass and no plasma treatment, serves as a baseline for comparing with subsequent samples S2 to S7 (Fig. 6a). This sample shows minimal adhesion of silver nanoparticle (AgNP) clusters to the PDMS surface, with the clusters averaging a size of about 1699.63 nm, as listed in Table 5. Figure 6b-g reveals the surface structure of samples that have been coated with silver nanoparticles at 17 kV and subjected to plasma treatment, demonstrating that each round of plasma treatment modifies the surface texture.

Figure 6h charts the changes in nanoparticle size across various prints and passes for samples S2-S7 (Table 5). Sample S2’s surface appears quite textured, and it’s dotted with numerous large AgNPs, having an average size of 732.54 nm (Fig. 6b). In contrast, Sample S3 presents a more refined and even surface with smaller AgNPs, averaging 376.8 nm in size (Fig. 6c). Moving to Sample S4, we observe the smoothest surface of all samples examined, with only a few nanoparticles visible and an average size of 295.4 nm (Fig. 6d). Sample S5, on the other hand, has a more textured surface with a visible presence of AgNPs, with an average particle size of 548.4 nm (Fig. 6e). Lastly, Samples S6 and S7 both display very textured surfaces teeming with clusters of AgNPs, having average sizes of 668.46 nm and 444.45 nm, respectively (Fig. 6f, g). These observations highlight the impact of plasma treatment on nanoparticle distribution and surface morphology in AgNP-coated PDMS samples.

Additional low-magnification SEM images are provided in Figure S5a-g of the supplementary material, and high-magnification SEM images can be found in Figure S6a-g.

SEM images of AgNP conductive structures on PDMS printed with (a) Single print without plasma (S1), (b) Single print with plasma (S2), (c) Single print with plasma, and immediate post-inert plasma treatment (S3), (d) Two print with plasma (S4), (e) Two times single print with plasma, and immediate post-inert plasma treatment after each print (S5), (f) Three print with plasma (S6), (g) Three times single print with plasma, and immediate post-inert plasma treatment after each print (S7), (h) Plot of average AgNP size in Ag conductive structures for samples S1 to S7.

The cross-sectional SEM image of Sample S1 shows that the average thickness of the nanoparticle clusters is about 0.19 μm (Fig. 7a). (Fig. 7b-g) present the varying layer thicknesses of samples coated with AgNP and subjected to plasma treatment at 17 kV. This visual data confirms that the layer’s texture changes with each additional plasma treatment, and its thickness generally grows. Specifically, Sample S2 has an average layer thickness of 1.69 μm, while Sample S3 shows a slightly less thickness of 1.55 μm (Fig. 7b, c).

Cross-sectional SEM images of AgNP conductive structures on PDMS printed with (a) Single print without plasma (S1), (b) Single print with plasma (S2), (c) Single print with plasma, and immediate post-inert plasma treatment (S3), (d) Two print with plasma (S4), (e) Two times single print with plasma, and immediate post-inert plasma treatment after each print (S5), (f) Three print with plasma (S6), (g) Three times single print with plasma, and immediate post-inert plasma treatment after each print (S7), (h) Plot of average print thickness of Ag conductive structure on PDMS for samples S1 to S7.

Sample S4 shows a more substantial increase in layer thickness up to 6.35 μm (Fig. 7d). In contrast, Sample S5’s thickness decreases slightly, measuring 4.99 μm (Fig. 7e). From the cross-sectional SEM images, it’s clear that Sample S5 is rougher and more porous than Sample S4. Samples S6 and S7 have even rougher layers, with average thicknesses of 6.85 and 5.97 μm, respectively (Fig. 7f, g). It’s noticeable that for samples that received a single print followed by another round of plasma treatment, the thickness of the layer went down. Although Samples S4 and S5 have thicker layers than Samples S2 and S3, the increase in thickness is less pronounced when comparing Samples S6 and S7 with S4 and S5 (Fig. 7h). This suggests that layer thickness does not consistently correlate with the number of printing passes and plasma treatments. Specifically, when comparing samples with and without additional plasma treatment—such as S4 (with 2 prints) and S5 (with 2 prints followed by 2 plasma treatments)—it is observed that the sample with the extra plasma treatment (S5) has a reduced print thickness. This reduction is attributed to material removal caused by the additional plasma bombardment. This pattern is also evident in Samples S2- S3 and S6- S7. Additional cross sectional SEM images are provided in Figure S7a-g of the supplementary material, and tilted SEM images can be found in Figure S8a-g. Detailed 3D profilometer surface texture analysis on samples S1 through S7, presented in Figure S9, reveals intricate insights into the root mean square (RMS) height variations across selected areas, enhancing our understanding of surface characteristics.

Bending and stretching studies

We further studied the resistance and resistivity of samples S2 to S7 with various displacements using custom-made stretch equipment. Sample S1 exhibits very high resistance, and measuring the resistance is challenging due to coating instability, which is excluded from the stretch test. At zero displacement, sample S2 has a resistance of 61.8 Ω and increasing resistance to 95 kΩ with 5 mm displacement (Fig. 8a). Sample S3 has an initial resistance of 41.2 Ω at zero displacement, and its resistance increases to 49 kΩ with 5 mm displacement. Sample S4 has an initial resistance of 6 Ω at zero displacement, and its resistance increases to 12 kΩ with 5 mm displacement. Sample S5 has an initial resistance of 1.36 Ω at zero displacement, and its resistance increases to 9 kΩ with 5 mm displacement. Sample S6 has an initial resistance of 1.74 Ω at zero displacement, and its resistance increases to 3.4 kΩ with 5 mm displacement. Sample S7 has an initial resistance of 1.87 Ω at zero displacement, and its resistance increases to 250Ω with 5 mm displacement.

The resistivity of the printed samples was measured at zero displacement, with each sample having dimensions of 1 cm length, 1 mm width, and thickness determined from cross-sectional SEM images. Compared to the baseline resistivity of the silver ink (ranging from 7.8 × 10⁻⁶ to 3.1 × 10⁻⁵ Ω·cm), Sample S5 showed the lowest resistivity at 6.79 × 10⁻⁵ Ω·cm, indicating excellent conductivity (Fig. 8b). Samples S6 and S7 also performed well, with resistivity values of 1.19 × 10⁻⁴ Ω·cm and 1.12 × 10⁻⁴ Ω·cm, respectively. In contrast, Samples S2, S3, and S4 exhibited higher resistivity, ranging from 3.81 × 10⁻⁴ to 1.04 × 10⁻³ Ω·cm, reflecting less effective conductivity.

Repetitive stretching studies

We examined the resistance behavior of conductive structures printed on PDMS when subjected to repeated mechanical stress. Specifically, samples S2 through S7 were each stretched to 1 mm beyond their original dimensions (10% stretching) over a series of 1000 cycles using a custom-designed stretching apparatus (Figure S10). This apparatus was uniquely capable of continuously stretching the samples while simultaneously recording the resistance data, ensuring high fidelity in data acquisition (Additional details are available at this GitHub repository: https://github.com/SoumadeepDe/Stretch-Machine.git). Sample S1 was excluded from the test series due to coating instability. The resistance measurements for each cycle were meticulously logged to observe the variations within each stretching cycle. For each cycle, 100 resistance readings were measured and plotted against stretching displacement. We then calculated and plotted the average resistance for each cycle throughout the 1000 cycles. We observed notable fluctuations in resistance over-stretching displacement for multiple stretching cycles.

Table 6 represents the resistance hysteresis of the 10th, 100th, and 1000th stretching cycles. Sample S2 showed an initial resistance of 61.8 Ω. When we stretched it to 0.8 mm on the 10th time, the resistance shot up to about 409.3 kΩ but returned to 79.36 Ω when relaxed. By the 100th stretch, it started at 46.43 ohms, went up to 2.82 kΩ when stretched to 1 mm, and then settled at 63.97 Ω when relaxed. At the 1000th stretch, the initial resistance was a bit higher at 49.3 Ω, peaked at 3.32 kΩ, and came down to 74.23 Ω at the end of the stretch.

Sample S3 began with a resistance of 41.18 Ω at the 10th stretch, increasing to 747 Ω at its most stretched and then decreasing to 47.81 Ω. The 100th stretch saw it start at 35.48 Ω, but then the resistance went off the chart at 0.7 mm, showing the limits of our equipment. It returned to 43.37 Ω afterward. The 1000th stretch began at 46.89 Ω, shot up again past our measuring capabilities at a smaller stretch of 0.54 mm, and dropped back to 58.05 Ω once unstretched. Sample S4 had a lower initial resistance of 6.02 Ω. At the 10th stretch, it went up to 39.64 Ω at 0.9 mm and came down to 7.93 Ω. By the 100th stretch, it began at 6.83 Ω, increased to 49.87 Ω at the same 0.9 mm stretch, and reduced to 8.17 Ω after relaxing. At the 1000th stretch, it started at 6.08 Ω, climbed to 63.86 Ω at 0.76 mm, and then went down to 9.59 Ω.

Sample S5 showed an initial resistance of 1.36 Ω. It reached 46.6 Ω at full stretch and settled at 2.01 Ω when unstretched. Its resistance rose to 142.8 Ω at the 100th stretch and returned to 2.78 Ω at rest. By the 1000th stretch, the resistance surged to 3.3 kΩ before relaxing to 3.04 Ω. Sample S6 presented notable fluctuations. Starting at 1.73 Ω, it spiked to 204 kΩ before breaking at the 10th stretch. It reconnected at 8.75 kΩ and ended at 46.06 Ω. At the 100th stretch, it went from 10.43 Ω to 22.6 kΩ, exceeding our equipment’s limits. It reconnected at 40.8 kΩ and finished at 25.6 Ω. At the 1000th stretch, it began at 20.07 Ω, increased to 8.9 kΩ, surpassed the measurement limit, and reconnected at 1.05 kΩ, finally decreasing to 37.7 Ω. Sample S7 started at 1.85 Ω and increased to 234.8 Ω at the 10th stretch, then reduced to 3.38 Ω. It began at 1.8 Ω at the 100th stretch, went up to 204.8 Ω, and returned to 2.34 Ω. At the 1000th stretch, it started at 2.45 Ω, increased slightly, then jumped beyond our measuring ability, reconnected to 4.4 Ω at 0.34 mm, and finished at 2.6 Ω.

We plotted the average resistance for 1000 cycles (Fig. 9a-f), with the average resistance calculated from the 100 data points of each stretching cycle. The continuous values of 65.53 kΩ represent breaking in the conductive structures and are detailed in the supplementary section. From the figure, sample S4 shows a much linear response in the average resistance concerning stretching displacement. After 1000 stretching, the average resistance of the S4 sample changes from 14.18 to 35.8 Ω (Fig. 9c). All other samples show breaking in the conductive structures during testing. This behavior indicates a breakdown in the conductive structure at 10% elongation, highlighting the material’s response to mechanical stress and its temporary resilience in electrical conductivity upon release of tension. This pattern of resistance fluctuation provides critical insights into the durability and mechanical limits of the conductive pathways embedded in the PDMS substrate.

We selected Sample S5 for printing an electronic circuit on a PDMS substrate after reviewing all data. This circuit was designed to accommodate nine SMD LEDs. The LEDs were attached using silver-based conductive glue instead of soldering to avoid damaging the printed circuit with high temperatures. After the glue was cured at room temperature, the circuit underwent various tests to assess its feasibility. These tests included bending, stretching, twisting, and rolling the circuit to evaluate its durability and performance under different conditions (Fig. 10).

Conclusion

We demonstrated the effectiveness of atmospheric plasma-aided inkjet printing in fabricating conductive structures on PDMS substrates using silver nanoparticle ink, specifically designed for wearable electronics. A stretchable electronic circuit was adeptly created on a flexible PDMS base, emphasizing the practicality of this advanced technology. Through SEM analysis, significant variations in surface morphology were noted, underscoring the critical role of plasma treatment in enhancing surface roughness and conductivity. The rapid inert gas post-print plasma treatments proved to be an effective low-temperature alternative to traditional sintering, significantly improving the electrical performance of the structures and ensuring their functionality in flexible applications. Optimal conditions were achieved at a plasma voltage of 17 kV, which fostered excellent adhesion and surface quality without damaging the substrate. The robustness and durability of these conductive paths were evaluated through rigorous testing—including stretching, bending, and resistivity analysis under dynamic conditions to mimic real-world usage. This research propels the field of materials science and catalyzes the development of flexible, durable, and efficient electronic components, positioning atmospheric plasma-aided inkjet printing as a transformative approach for the future of wearable technology.

Data availability

Detailed information of custom-made stretching banding equipment is available on GitHub repository via this link. https://github.com/SoumadeepDe/Stretch-Machine.git.

References

Dawkins, R. C., Wen, D., Hart, J. N. & Vepsäläinen, M. A screen-printed Ag/AgCl reference electrode with long-term stability for electroanalytical applications. Electrochim. Acta 393, (2021).

Lee, K. Y. et al. Development of a polydimethylsiloxane-based electrode array for Electrocorticography. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 7, (2020).

Chen, C. Y., Chang, C. L., Chien, T. F. & Luo, C. H. Flexible PDMS electrode for one-point wearable wireless bio-potential acquisition. Sens. Actuators Phys. 203, 20–28 (2013).

Ye, Z., Li, Q., Zhang, R., Zhang, P. & Gui, L. Fabrication of a thin PDMS film with complex liquid metal electrodes embedded and its application as skin sensors. RSC Adv. 12, 8290–8299 (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. Flexible and stretchable dry active electrodes with pdms and silver flakes for bio-potentials sensing systems. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 12255–12268 (2021).

Lee, J., Chung, S., Song, H., Kim, S. & Hong, Y. Lateral-crack-free, buckled, inkjet-printed silver electrodes on highly pre-stretched elastomeric substrates. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 46, (2013).

Tang, J. et al. Highly stretchable electrodes on wrinkled polydimethylsiloxane substrates. Sci. Rep. 5, (2015).

Chlaihawi, A. A., Narakathu, B. B., Emamian, S., Bazuin, B. J. & Atashbar, M. Z. Development of printed and flexible dry ECG electrodes. Sens. Biosensing Res. 20, 9–15 (2018).

Shrestha, M., Depari, L., Shakerzadeh, M., Shivakumar, R. & Teo, E. H. T. Ink-based transparent compliant electrode for direct coating on untreated hydrophobic PDMS surface. Sens. Actuators Rep. 5, (2023).

Li, C. Y. & Liao, Y. C. Adhesive Stretchable printed Conductive Thin Film patterns on PDMS Surface with an Atmospheric plasma treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8, 11868–11874 (2016).

Liu, C. X. & Choi, J. W. Patterning conductive PDMS nanocomposite in an elastomer using microcontact printing. J. Micromech. Microeng. 19, (2009).

Tas, M. O. et al. Highly stretchable, Directionally Oriented Carbon Nanotube/PDMS Conductive films with enhanced sensitivity as wearable strain sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11, 39560–39573 (2019).

Uchil, S. B. A. & Mazumder, N. T. K. S. C. Md. A. A. P. S. K. K. M. S. S. The revolution of PDMS microfluidics in cellular biology. Crit Rev Biotechnol 43, 465–483 (2023).

Fujii, T. PDMS-based microfluidic devices for biomedical applications. Microelectron. Eng. 61–62, 907–914 (2002).

Raj, M. & Chakraborty, S. K. PDMS microfluidics: A mini review. Journal of Applied Polymer Science vol. 137 Preprint at (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/app.48958

PDMS_and_its_Suitability_for_Analytical_Microfluidic_Devices.

Yadhuraj, S. R., Sudarshan, B. G. & Kumar, P. Mahesh Kumar, D. Study of PDMS Material for ECG electrodes. Mater. Today Proc. 5, 10635–10643 (2018).

Shrestha, M. et al. Emerging tunable window technologies for active transparency tuning. Appl. Phys. Reviews, 9(3). (2022).

Zhou, D. et al. Ultrafast assembly and healing of nanomaterial networks on polymer substrates for flexible hybrid electronics. Appl. Mater. Today. 22, 100956 (2021).

Rogers, J. A., Someya, T. & Huang, Y. Materials and Mechanics for Stretchable Electronics. https://www.science.org

Engel, J. M. et al. Multi-layer embedment of conductive and non-conductive pdms for all-elastomer mems. Tech. Digest - Solid-State Sens. Actuators Microsystems Workshop. 316–319. https://doi.org/10.31438/trf.hh2006.81 (2006). Transducer Research Foundation.

Heng, K. R., Ahmed, A. S., Shrestha, M. & Lau, G. K. Strong dielectric-elastomer grippers with tension arch flexures. in Electroactive Polymer Actuators and Devices (EAPAD) 2017 (ed. Bar-Cohen, Y.) vol. 10163 101631ZSPIE, (2017).

El-Atab, N. et al. Soft actuators for soft robotic applications: a review. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2, (2020).

Han, B., Zhang, Y. L., Chen, Q. D. & Sun, H. B. Carbon-Based Photothermal Actuators. Advanced Functional Materials vol. 28 Preprint at (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201802235

Zheng, Q. et al. Smart Actuators Based on External Stimulus Response. Frontiers in Chemistry vol. 9 Preprint at (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.650358

Singh, A. D. & Patrikar, R. M. Design and fabrication of PDMS-based electrostatically actuated MEMS cantilever beam. Micro Nano Lett. 15, 302–307 (2020).

Han Min, S., Asrulnizam, A. M., Atsunori, M. & Mariatti, M. Properties of Stretchable and flexible strain Sensor based on Silver/PDMS nanocomposites. Mater. Today Proc. 17, 616–622 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. MWCNTs/PDMS composite enabled printed flexible omnidirectional strain sensors for wearable electronics. Compos. Sci. Technol. 226, 109518 (2022).

Jayathilaka, W. A. D. M. et al. Significance of Nanomaterials in Wearables: A Review on Wearable Actuators and Sensors. Advanced Materials vol. 31 Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201805921

Chen, J. et al. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based flexible resistive strain sensors for wearable applications. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) vol. 8 Preprint at (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/app8030345

Qi, D., Zhang, K., Tian, G., Jiang, B. & Huang, Y. Stretchable Electronics based on PDMS substrates. Adv. Mater. 33, (2021).

Seghir, R. & Arscott, S. Extended PDMS stiffness range for flexible systems. Sens. Actuators Phys. 230, 33–39 (2015).

Goh, G. L., Zhang, H., Chong, T. H. & Yeong, W. Y. 3D Printing of Multilayered and Multimaterial Electronics: A Review. Advanced Electronic Materials vol. 7 Preprint at (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/aelm.202100445

Hadeler, S., Bengsch, S., Prediger, M. S. & Wurz, M. C. Transfer Printing of Conductive Thin Films on PDMS with Soluble Substrates for Flexible Biosensors †. Engineering Proceedings 2, (2020).

Wolf, M. P., Salieb-Beugelaar, G. B. & Hunziker, P. PDMS with designer functionalities—Properties, modifications strategies, and applications. Progress in Polymer Science vol. 83 97–134 Preprint at (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.06.001

Goh, G. L., Agarwala, S. & Yeong, W. Y. High resolution aerosol jet printing of conductive ink for stretchable electronics. in Proceedings of the International Conference on Progress in Additive Manufacturing vols -May 109–114 (Pro-AM, 2018). (2018).

Chiolerio, A. et al. Inkjet-printed PEDOT:PSS electrodes on plasma-modified PDMS nanocomposites: quantifying plasma treatment hardness. RSC Adv. 4, 51477–51485 (2014).

IEEE Sensors Council & Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. IEEE SENSORS 2014: Proceedings : Valencia Conference Centre, Valencia, Spain, November 2–5, (2014).

Chung, S. et al. Inkjet-printed stretchable silver electrode on wave structured elastomeric substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett., 98(15). (2011).

Abu-Khalaf, J. M., Al-Ghussain, L. & Al-Halhouli, A. Fabrication of stretchable circuits on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) pre-stretched substrates by inkjet printing silver nanoparticles. Materials 11, (2018).

Dey, A. et al. Plasma jet based in situ reduction of copper oxide in direct write printing. J. Vacuum Sci. Technol. B Nanatechnol. Microelectronics: Mater. Process. Meas. Phenom. 37, (2019).

Ramamurti, R. et al. Atmospheric pressure plasma printing of nanomaterials for IoT applications. IEEE Open. J. Nanatechnol. 1, 47–56 (2020).

Doshi, P. et al. Printing of electromagnetic interference shielding materials. Flex. Print. Electron. 8, (2023).

Gutierrez, D. H., Doshi, P., Nordlund, D. & Gandhiraman, R. P. Plasma jet printing of metallic patterns in zero gravity. Flex. Print. Electron. 7, (2022).

Sonawane, A., Mujawar, M. A. & Bhansali, S. Effects of cold atmospheric plasma treatment on the morphological and optical properties of plasmonic silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 31, (2020).

Jalajamony, H. M., Nair, M., Doshi, P. H., Gandhiraman, R. P. & Fernandez, R. E. Plasma Printed Antenna for Flexible Battery-Less Smart Mask for Lung Health Monitoring. in FLEPS 2023 - IEEE International Conference on Flexible and Printable Sensors and Systems, ProceedingsInstitute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., doi: (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/FLEPS57599.2023.10220224

Gandhiraman, R. P. et al. Plasma jet printing of electronic materials on flexible and nonconformal objects. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 20860–20867 (2014).

Gandhiraman, R. P., Nordlund, D., Jayan, V., Meyyappan, M. & Koehne, J. E. Scalable low-cost fabrication of disposable paper sensors for DNA detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 22751–22760 (2014).

Gandhiraman, R. P. et al. Plasma jet printing for flexible substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, (2016).

Daniel, H., Gutierrez Ranajoy Bhattacharya, P. D. D. N. & Gandhiraman, R. P. Plasma jet printing of copper and silver antennas operating at 2.4 GHz. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 38, 790–801 (2024).

Doshi, P. et al. Plasma Jet Printing of Diamond and Silicon. IEEE J. Flex. Electron. 1–1 https://doi.org/10.1109/JFLEX.2024.3384330 (2024).

Nordlund, D., Doshi, P., Gutierrez, D. & Gandhiraman, R. Plasma Jet Printing for Printed Electronics. in IFETC 2023–5th IEEE International Flexible Electronics Technology Conference, ProceedingsInstitute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., doi: (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/IFETC57334.2023.10254802

Park, C. S. et al. Conductive polymer synthesis with single-crystallinity via a novel plasma polymerization technique for gas sensor applications. Materials 9, (2016).

Manzi, J., Kandadai, N., Gandhiraman, R. P. & Subbaraman, H. Plasma Jet Printing: an introduction. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 70, 1548–1553 (2023).

Dey, A. et al. Plasma Jet Printing and in situ reduction of highly acidic Graphene Oxide. ACS Nano. 12, 5473–5481 (2018).

Kim, Y., Ren, X., Kim, J. W. & Noh, H. Direct inkjet printing of micro-scale silver electrodes on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microchip. J. Micromech. Microeng. 24, (2014).

Metin, H. & Esen, R. Annealing effects on optical and crystallographic properties of CBD grown CdS films. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 18 (7), 647–654. https://doi.org/10.1088/0268-1242/18/7/308 (2003).

Kaneva, N. V., Kaneva, N. V. & Dushkin, C. D. Preparation of Nanocrystalline Thin films of ZnO by Sol-Gel Dip Coating. Article Bulgarian Chem. Commun. 43 (2011). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260843683

Acknowledgements

Support from National Science Foundation grants #2100930 and #2112595 (CREST) is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J. conducted the primary experiments, designed the plasma printing protocols, and carried out the characterization. S.D. contributed to the primary experimental design and protocol development, and also designed and executed the dynamic bending stress experiments. A.K. performed the XRD analysis, contributed to the bending and stretching experiments, and assisted with manuscript writing. F.D made PDMS substrates and conducted experiments. G.S. and R.F. supervised the work and manuscript writing. R.F. is the Principal Investigator of the NSF grants that funded this proposal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jalajamony, H.M., Aliyana, A.K., De, S. et al. Plasma-aided direct printing of silver nanoparticle conductive structures on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) surfaces. Sci Rep 14, 31154 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82439-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82439-y

This article is cited by

-

Direct printing of metal oxide nanostructures for wearable electrochemical sensing

Scientific Reports (2025)