Abstract

Prefabricated construction involves manufacturing components in a factory and then transporting them to a construction site for assembly, yielding resource savings and improved efficiency. However, the large size and weight of prefabricated components, along with strict delivery requirements, introduce logistical challenges, such as increased carbon emissions during transport and site congestion. This study addresses the dual-objective vehicle scheduling problem for prefabricated components. It proposes a dual-objective optimization model for prefabricated component logistics, guided by the Just-In-Time (JIT) strategy. The model comprehensively considers on-site and off-site logistics, accounts for uncertainties, and details the logistics process for each component. Its objectives are to reduce carbon emissions during logistics and enhance customer satisfaction. An improved Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) is used to solve the model, offering enhanced solution diversity and local search capabilities. The model is validated through case studies, with sensitivity analyses conducted to further assess performance. Results indicate that the proposed model provides effective vehicle scheduling solutions that meet optimization objectives. Compared to traditional logistics models, the JIT logistics model demonstrates greater resilience to uncertainty, providing scientifically based decision support for logistics management in prefabricated construction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an emerging construction model, prefabricated construction involves the mass production of structural components in a factory-like assembly line, which are then transported and assembled on-site1. This model significantly improves construction speed in prefabricated projects. However, due to the large size and weight of prefabricated components, the transportation process has high requirements for quality, safety, and timeliness, characterized by short transport cycles and high transport density. These factors present challenges for logistics scheduling2, making it essential to optimize vehicle scheduling for prefabricated components in prefabricated construction.

The logistics process of prefabricated components generally includes loading, transportation, unloading (or direct hoisting), and return phases. When multiple vehicle types are available, the transportation combinations vary. At present, scheduling primarily relies on subjective methods, such as manual experience analysis, which often lack comprehensive consideration of factors such as timing coordination across logistics phases, transportation combinations of prefabricated components, and unloading capacity at construction sites3. This results in inefficient resource allocation in scheduling plans, leading to vehicle congestion, delivery delays, and construction delays4. Therefore, this study aims to enhance the rationality of vehicle scheduling schemes by incorporating various phases’ time consumption and transportation combinations into the model.

Currently, upon arriving at the construction site, prefabricated components are generally placed in storage areas. However, in densely built cities, construction sites often lack adequate storage space for prefabricated components. For instance, in Hong Kong, over 80% of prefabricated construction sites face space constraints5 and high secondary handling costs6. The Just-In-Time (JIT) logistics model offers a solution, allowing transportation plans to be adjusted promptly according to actual construction progress and requirements7, although it imposes stricter requirements on vehicle scheduling schemes. JIT-based prefabricated component distribution has two primary characteristics: (1) Multi-dimensional workspaces8, encompassing manufacturing, off-site logistics, and on-site logistics spaces. Efficient coordination among these spaces is critical, as poor coordination between any two can lower the scheduling efficiency of the entire scheme; and (2) Logistics uncertainty, including uncertainty in transport times and hoisting times for different component types. In practice, factors such as urban traffic congestion and crane operation speed at construction sites cause dynamic changes in transport and hoisting times, requiring vehicle scheduling schemes to incorporate sufficient tolerance for these uncertainties. Thus, this study quantifies logistics uncertainties and designs a JIT-based vehicle scheduling scheme to ensure a smooth transition of each prefabricated component between various workspaces.

This study uses carbon emissions and customer satisfaction as two optimization objectives to derive the vehicle scheduling scheme for prefabricated component transportation through bi-objective optimization. Existing research shows that prefabricated construction reduces lifecycle carbon emissions by over 15% compared to traditional cast-in-place construction. However, the logistics phase sees a significant increase in carbon emissions, exceeding 20%9,10,11. The core of the JIT logistics model lies in timely delivery; higher customer satisfaction indicates fewer delays in the logistics phase12.

The problem addressed in this study belongs to the category of time-window, multi-vehicle type scheduling problems, classified as NP-hard13. In recent years, intelligent optimization algorithms have been widely applied in various industrial fields, such as classical Genetic Algorithms (GA), Tabu Search (TS), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Simulated Annealing (SA)14,15,16,17,18. However, as theoretical research progresses, the limitations of these algorithms in solving multi-objective optimization problems have become more pronounced. To address this, this study adopts the NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm-II) and improves it based on the classic algorithm to enhance local search capability, explore the solution space more effectively, and avoid local optima.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review, introducing optimization methods for prefabricated construction logistics, the application of JIT logistics modes, and algorithm research. Section 3 describes the research methodology. Section 4 presents case validation and designs a sensitivity analysis. Section 5 discusses the findings, and Sect. 6 concludes with the presentation of conclusions and potential future research directions.

Literature review

Logistics for prefabricated components

The most significant difference between prefabricated construction and traditional construction is that the components of prefabricated buildings are produced in factories and then transported to the construction site for installation19. This extends the logistics management of prefabricated construction to include the entire process of manufacturing, transportation, delivery, and installation of the components20. However, the logistics process in prefabricated construction is fraught with coordination challenges due to the large investments, long construction cycles, involvement of multiple units, and the complexity of the construction process21. Therefore, logistics optimization in prefabricated construction plays a crucial role in promoting its development.

Existing research has provided valuable insights for optimizing the logistics process in prefabricated construction, these is shown in Table 1. However, most of these studies focus on independent optimization of various logistics stages, with limited research on multi-stage collaborative optimization. Additionally, existing research primarily concentrates on single-objective optimization, considering only one objective function during the optimization process. Single-objective optimization models often fail to adequately balance conflicting objectives in practical scenarios, thereby reducing the feasibility of optimization solutions. To address these issues, this study simultaneously considers both on-site and off-site logistics for prefabricated components, resulting in a more comprehensive and holistic model. Furthermore, a dual-objective optimization approach is adopted to achieve a balance between different objectives, thereby enhancing the equity and effectiveness of the proposed model.

JIT logistics mode

One notable characteristic of prefabricated construction is its significantly faster construction speed compared to cast-in-place construction. The coordination of logistics and construction for prefabricated components is one of the key factors in accelerating construction speed. The traditional logistics process for prefabricated components is shown in Fig. 1. In contrast, the application of the JIT strategy is considered to be effective in improving the logistics of prefabricated components from the production factory to the construction project41.

In summary, Table 2 has shown some relevant research on JIT logistics applications in prefabricated construction, although the JIT strategy has been applied in the prefabricated component supply chain, existing research primarily focuses on solving optimal delivery batch sizes under the JIT mode, without specific consideration for individual prefabricated components. This lack of depth in the optimization process prompted this study to address this research gap. When establishing the model, both transportation and lifting processes were incorporated, thereby expanding and deepening the implications of the JIT strategy within prefabricated component logistics. Additionally, this research reasonably predicted and quantified uncertain factors such as transportation and installation times, enhancing the accuracy and practical value of the study.

Algorithms for vehicle scheduling problems

For vehicle scheduling problems, existing research solutions mainly fall into two categories: exact algorithms and heuristic algorithms.

The main advantage of exact algorithms is that they can find the precise optimal solution or an approximation very close to it through exhaustive search or mathematical optimization techniques23. In the field of logistics optimization for prefabricated construction, researchers have explored the application of mixed-integer linear programming51, mixed-integer programming52, stochastic programming23, and constraint programming53. However, when dealing with large-scale problems, the computational complexity of exact algorithms may grow exponentially, leading to increased solution times. As a result, scholars have widely used heuristic algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms (GA), Tabu Search (TS), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Simulated Annealing (SA)14,15,16,17,18 to address scheduling issues in prefabricated construction. Table 3 has shown some algorithmic approaches for scheduling and logistics in prefabrication.

In summary, this study employs the NSGA-II algorithm to solve the model. Building upon previous research, this paper enhances the local search and evolutionary aspects of the NSGA-II algorithm. This improvement not only strengthens the algorithm’s local search capabilities but also better explores the solution space, thus avoiding convergence to local optima.

Research methodology

Hypotheses of model

Compared to the traditional logistics model, the proposed JIT logistics model reduces unloading and storage processes, as shown in Fig. 2. Upon arrival at the construction site, transport vehicles coordinate with on-site lifting equipment for the lifting work. Therefore, the proposed model includes four stages: prefabricated component loading, transportation, lifting, and return.

Based on the logistics model, the following assumptions are made:

-

1.

Transportation routes are fixed and known.

-

2.

The prefabricated component factory can complete all order requirements on time.

-

3.

The transportation time is solely affected by traffic congestion.

-

4.

Each transport vehicle can only carry one type of component.

-

5.

The loading and hoisting stages are limited to handling only one vehicle at a time.

Variable setting

The timeline-based model is illustrated in Fig. 3. The symbols and their descriptions used in the modeling process are as shown in Table 4.

-

1.

Loading phase variables.

The time a transport vehicle waits for the preceding vehicle during the loading phase is represented by DATsn, and the calculation formula is as follows:

$$\:{DAT}_{sn}={CT}_{sn}-{ZT}_{y}-{CT}_{s,n-1}$$(1) -

2.

Transportation phase variables.

During the transportation phase, this paper defines the variables of vehicle transportation time \(\:{YT}_{sn}\);, vehicle arrival time DTsn, site time window constraints (TWAs, TWBs, TWCs, TWDs), and waiting times after vehicle arrival at the construction site (DBTsn and DCTsn), corresponding to two waiting scenarios after the vehicle arrives at the construction site: DBTsn is the waiting time when the vehicle arrives earlier than the earliest time point of the time window, and DCTsn is the waiting time for the completion of the hoisting by the previous vehicle. The calculation formulas are as follows:

$$\:{YT}_{sn}=\sum\:_{k=0}^{m-1}{\int\:}_{{t}_{k}}^{{t}_{k+1}}\frac{{D}_{ps}}{{V}_{0}\cdot\:{TPI}_{k}\cdot\:m}{d}_{t}$$(2)$$\:{DT}_{sn}={CT}_{sn}+{YT}_{sn}$$(3)$$\:{DBT}_{sn}={TWA}_{s}-{DT}_{sn}$$(4)$$\:{DCT}_{sn}={LFT}_{sa}\times\:{PM}_{sna}-({LT}_{s,n-1}-{DT}_{sn})$$(5)The total waiting time for transport vehicles, denoted as TDTsn, is calculated using the following formula:

$$\:{TDT}_{sn}={DAT}_{sn}+\gamma\:\cdot\:{DBT}_{sn}+\delta\:\cdot\:{DCT}_{sn}$$$$\:\gamma\:=\left\{\begin{array}{l}1,{DBT}_{sn}>0\\\:0,{DBT}_{sn}\le\:0\end{array},\:\:\:\delta\:=\left\{\begin{array}{l}1,{\:DCT}_{sn}>0\:\:\text{and}\text{\:}\text{\:}{DBT}_{sn}\le\:0\\\:0,{\:DCT}_{sn}\le\:0\:\:\text{and}\text{\:\:}{DBT}_{sn}\le\:0\end{array}\right.\right.$$(6) -

3.

Hoisting and Return Phase Variables.

During the hoisting and return phases, this study defines the variables of hoisting time TLFTsn, the time when the transport vehicle leaves the construction site LTsn, the return time HTsn, and the time when the vehicle returns to the factory FTsn. The calculation formulas are as follows:

$$\:{TLFT}_{sn}={LFT}_{sa}\cdot\:{PM}_{sna}$$(7)$$\:{LT}_{sn}={DT}_{sn}+\left(\gamma\:\cdot\:{DBT}_{sn}+\delta\:\cdot\:{DCT}_{sn}\right)+{TLFT}_{sn}$$$$\:\gamma\:=\left\{\begin{array}{l}1,{DBT}_{sn}>0\\\:0,{DBT}_{sn}\le\:0\end{array},\:\:\:\delta\:=\left\{\begin{array}{l}1,{\:DCT}_{sn}>0\:\text{and}\text{\:}\text{\:}{DBT}_{sn}\le\:0\\\:0,{\:DCT}_{sn}\le\:0\:\text{and}\text{\:}\text{\:}{DBT}_{sn}\le\:0\end{array}\right.\right.$$(8)$$\:{HT}_{sn}=\sum\:_{k=0}^{m-1}{\int\:}_{{t}_{k}}^{{t}_{k+1}}\frac{{D}_{ps}}{{V}_{0}^{{\prime\:}}\cdot\:{TPI}_{k}\cdot\:m}{d}_{t}$$(9)$$\:{FT}_{sn}={LT}_{sn}+{HT}_{sn}$$(10)

Dual-objective optimization model

The optimization objectives of the model proposed in this study are to minimize carbon emissions and maximize customer satisfaction.

-

1.

Carbon Emission Optimization Objective.

This study uses the carbon emission factor method59 to calculate carbon emissions. Here, the carbon emissions generated during the loading phase are defined as EA, the transportation phase (loaded and unloaded) as EB, and the hoisting phase as ED. The uncertainty of traffic conditions is quantified using the real-time Traffic Congestion Index TPI, as shown in Eq. (2). The uncertainty of hoisting time is quantified using a normal distribution, as shown in Eq. (11).

$$LF{T_{sa}}\sim N\left( {\overline {{t_{sa}}} ,{{\left( {\frac{{0.1 \times \overline {{t_{sa}}} }}{{1.96}}} \right)}^2}} \right)$$(11) -

2.

Customer Satisfaction Optimization Objective.

Customer satisfaction is an essential indicator for measuring the level of satisfaction with logistics services. Here, satisfaction is quantified by establishing constraints on time windows. In the logistics of prefabricated components, vehicle pile-up can occur when the connection between transport trips is not smooth. To address this, the proposed JIT logistics model not only requires that prefabricated components be delivered within the time window but also demands smooth connections between transport vehicles. The method divides customer satisfaction into two parts: satisfaction with the arrival time of transport vehicles, denoted as \(\:{C}_{sn}\), and satisfaction with the connection between transport vehicles, denoted as \(\:{C}_{sn}^{{\prime\:}}\), as shown in Fig. 4. The model also defines the waiting time for transport vehicles, GTsn.

-

3.

Dual-Objective mathematical model.

The dual-objective mathematical model for the JIT logistics of prefabricated components is as follows:

$$\:min\:TE=EA+EB+ED$$(12)$$\:max\:TC=\sum\:_{s=1}^{s}\sum\:_{n=1}^{n}\frac{{C}_{sn}+{\text{C}}_{sn}^{{\prime\:}}}{2\cdot\:{s}_{n}}$$(13)$$\:\:{CT}_{sn}\ge\:FT$$(14)$$\:\:\sum\:_{s=1}^{s}\sum\:_{a=1}^{a}{PN}_{sa}\le\:\sum\:_{s=1}^{s}\sum\:_{a=1}^{a}\sum\:_{y=1}^{y}{B}_{say}$$(15)$$\:{CT}_{sn}-{CT}_{s,n-1}\ge\:{ZT}_{y}$$(16)$$\:M<\sum\:_{s=1}^{s}{S}_{n}$$(17)$$\:{DT}_{sn}\le\:{TWD}_{s}$$(18)$$\:{PM}_{sna}\le\:{B}_{say}$$(19)Equation (14): The departure time of the transport vehicle must be later than the start time of the prefabricated component factory; Eq. (15): The number of prefabricated components transported to the construction project must meet the demand of that project; Eq. (16): The departure time interval between the two nearest vehicles should not be less than the loading time of the latter vehicle; Eq. (17): The sum of trips made to various construction projects should be greater than the total number of delivery vehicles; Eq. (18): This represents the hard time window requirements of the construction project; Eq. (19): This denotes the loading capacity constraints of the transport vehicles.

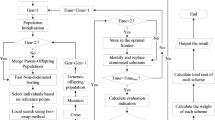

Improved NSGA-II algorithm

This study has improved upon the NSGA-II algorithm by incorporating enhancements from the hill-climbing algorithm for local search and evolutionary phase parameter adjustments. By integrating the local search capabilities of the hill-climbing algorithm with the global search abilities of NSGA-II, the model more finely explores the solution space near the current solution, increasing the probability of discovering high-quality solutions in local areas. An adaptive strategy is introduced to dynamically adjust the crossover and mutation operators, that is, to adaptively adjust the probabilities of crossover and mutation based on the state of the population and the process of evolution, thus better exploring the solution space and avoiding local optima. The adaptive crossover probability is shown in Eq. (20), and the adaptive mutation probability is shown in Eq. (21):

In Eq. (20), N represents the total number of iterations; \(\:{P}_{c}^{{\prime\:}}\) denotes the adaptive crossover probability for the nth iteration; \(\:{P}_{c}\) indicates the preset fixed crossover probability; \(\:\epsilon\:\) is a constant, with a value set to 1.5. In Eq. (21), \(\:{P}_{m}^{max}\left(i\right)\) is the predefined maximum mutation probability; \(\:{P}_{c}\left(i\right)\) is the mutation probability for individual i; \(\:f\left(i\right)\) is the fitness of individual i.

The design of the improved NSGA-II algorithm process is as follows:

Step 1: Chromosome encoding. The study addresses the vehicle scheduling problem with a mixed fleet and mixed time windows, employing a hybrid encoding method that includes both integer and discrete encodings for chromosome coding, as shown in Fig. 5.

Step 2: Initialization of the population. The initial population is created by randomly generating codes for vehicle types and transport sequences.

Step 3: Fitness evaluation. Fitness is assessed by considering both satisfaction and energy consumption as objective functions. The calculation expressions are as shown in Eqs. (22) and (23). After determining the fitness functions, the fitness of individuals is evaluated using fast non-dominated sorting, crowding distance calculations, and crowding distance operator comparisons, establishing the Pareto front of the initial population.

Step 4: Evolution. The selection process employs a binary tournament selection method. The crossover process involves a mix of single-point and sequence crossover, with single-point crossover mainly used for encoding vehicle types and sequence crossover for transport sequences encoding. During the mutation process, single-point mutation is applied to genes representing vehicle types, and swap mutation to genes representing transport sequences.

Step 5: Formation of a new population. The study adopts a replacement strategy to form a new population, where offspring replace part or all of the parents.

Step 6: Iteration repetition. After each generation evolves, it is determined whether the termination conditions are met. Termination conditions are typically set based on the problem’s requirements, such as reaching the maximum number of iterations or a threshold value of the objective function. If the termination conditions are met, the algorithm stops and returns the optimal solution found; otherwise, it resumes fitness evaluation and continues until the termination conditions are satisfied.

In conclusion, the improved NSGA-II algorithm process is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Case study

This section takes the real tasks of a prefabricated component factory in Chongqing as a research case and optimizes the vehicle scheduling scheme through the proposed model. Table 5 shows the prefabricated component demand data of three construction projects from July 4 to July 7, 2023; Table 6 presents the basic information of the construction projects. Detailed information on the loading capacity of transportation vehicles, energy consumption data, transportation routes, traffic congestion index, and the energy consumption data of loading and hoisting equipment can be found in the appendix.

Results

The reasonable setting of algorithm parameters can better unleash the optimization performance of the algorithm. After tuning, the specific parameters of the optimized model are as follows: population size (NP = 100), initial crossover probability (Pc = 0.8), initial mutation probability (Pm = 0.1), and number of iterations (Max gen = 500). The solution is computed using MATLAB.

Based on the tendencies of the solutions towards two different objective functions, 10 sets of different objective function values are derived, as shown in Table 7. From the table, it is evident that in the results of the proposed JIT logistics model, Scheme 1 has the lowest carbon emissions and Scheme 10 has the highest satisfaction. The corresponding values are 7033.73 kg and 10201.57 kg for carbon emissions, and 83.77% and 97.34% for customer satisfaction, respectively. Scheme 6 is the optimal choice selected by the proposed model, as it achieves a balance between carbon emissions and customer satisfaction. Detailed data are shown in Table 8. (only data for July 4th is presented here; complete data from July 4th to July 7th can be found in the appendix).

Upon analyzing the Vehicle Scheduling Scheme, it is evident that the earliest departing transport vehicle on each workday will preemptively arrive at the designated construction site to wait. While this early arrival may slightly diminish the satisfaction of these particular trips, it facilitates the seamless coordination with subsequent transport vehicles throughout the day, thereby ensuring that customer satisfaction for the majority of later trips reaches 100%. Overall, out of the 59 trips in the scheme, 49 achieved a customer satisfaction rate of 100%, with an impressive average satisfaction rate of 96.1%. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the optimized scheme.

Sensitivity analysis design

In order to explore the impact of vehicle type, transportation time uncertainty, and hoisting time uncertainty on the optimization objectives, this section designs a sensitivity analysis for the aforementioned three factors.

-

1.

Vehicle Type.

The type of transportation vehicle directly affects the number of prefabricated components transported per trip. Vehicles with larger carrying capacity can reduce the number of trips but will produce more carbon emissions. In the aforementioned case, a mixed fleet including vehicles with a carrying capacity of 20t, 15t, and 8t was used to transport prefabricated components. To explore the impact of different fleet combinations on the optimization objectives, the case of a single vehicle type is now optimized.

-

2.

Transportation Time Uncertainty.

This paper uses the regional Traffic Performance Index (TPI) provided by big data to study transportation time uncertainty. This index can reflect the real traffic congestion situation and thus calculate the transportation time uncertainty for different time periods. To further explore the impact of transportation time uncertainty on the optimization objectives, three transportation time scenarios are considered: the first assumes no traffic congestion; the second assumes traffic congestion throughout the journey, reducing transportation speed by 10%; the third uses real traffic congestion conditions.

-

3.

Hoisting Time Uncertainty.

The previous assumption was that the installation time of prefabricated components generally follows a normal distribution. Here, the following three scenarios are considered to compare the impact of construction time uncertainty on the optimization objectives. The first scenario assumes that the installation time of a single prefabricated component (LFT) remains fixed and equal to the average construction speed \(\:\stackrel{-}{{t}_{sa}}\); the second scenario assumes that the installation time of a single prefabricated component has a 95% probability of fluctuating within \(\:\stackrel{-}{{t}_{sa}}\pm\:0.1\stackrel{-}{{t}_{sa}}\); the third scenario assumes that the installation time of a single prefabricated component has a 95% probability of fluctuating within \(\:\stackrel{-}{{t}_{sa}}\pm\:0.2\stackrel{-}{{t}_{sa}}\).

Sensitivity analysis results

-

1.

Vehicle Type.

In the case of a single vehicle type, both the minimum carbon emissions and the maximum customer satisfaction show a decreasing trend as the load capacity of transport vehicles increases, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The results indicate that scheduling flexibility is higher for mixed fleets, thus minimizing carbon emissions. The proposed model emphasizes the coordination between vehicles, resulting in higher customer satisfaction compared to fleets consisting of single types of vehicles with loads of 15t and 20t. Therefore, to balance carbon emissions and customer satisfaction, mixed fleets should be used; when only customer satisfaction is required, fleets with the smallest load capacity (8t) can be chosen.

-

2.

Transportation Time Uncertainty.

Under both the traditional logistics model (where construction projects can store prefabricated components) and the JIT model, optimization solutions for carbon emissions and satisfaction were carried out for three scenarios, extracting the optimal values after 500 iterations, as shown in Table 9.The results indicate that in terms of carbon emissions, with a 10% increase in traffic congestion, the carbon emissions for the traditional logistics model increased by 10.81%, while the JIT model saw an increase of 5.83%. Under real traffic congestion conditions, the traditional logistics model’s carbon emissions increased by 29.66%, while the JIT model’s increased by 16.76%. This demonstrates that the proposed JIT logistics model has stronger resilience in the face of traffic uncertainty regarding carbon emissions. In terms of customer satisfaction, although changes in traffic conditions lead to a reduction in satisfaction, the decrease in satisfaction for the proposed JIT logistics model is only around 1%, indicating that the proposed model can effectively reduce the impact of transportation time uncertainty on satisfaction.

Table 9 The impact of uncertain transportation time on carbon emissions and satisfaction. -

3.

Hoisting Time Uncertainty.

The results of solving for different hoisting time distributions are shown in Table 10. In terms of carbon emissions, compared to a fixed hoisting time, the increase in carbon emissions caused by a 95% probability of hoisting time varying within ± 10% is 3.58%; when there is a 95% probability of hoisting time varying within ± 20%, the increase in carbon emissions is 15.26%. This indicates that the proposed model can effectively control carbon emissions in the face of uncertainty in hoisting time, but the control effect will be affected when the variation in construction time is large. In terms of customer satisfaction, the variation in hoisting time has a minor impact on customer satisfaction because the proposed model sets a high standard for measuring customer satisfaction. During algorithmic solution, customer satisfaction is prioritized at the expense of optimizing carbon emissions, which aligns with actual production conditions.

Table 10 The impact of uncertain hoisting time on carbon emissions and satisfaction.

Discussion

Impact of logistics mode on optimization effect

In order to analyze the impact of different logistics modes on optimization objectives, a traditional logistics model for prefabricated components is established here and compared with the JIT logistics model proposed in this paper. The Pareto frontiers of delivery schemes obtained by solving the two logistics models are shown in Fig. 8, where each point contains both carbon emission and satisfaction objective values, representing a set of non-inferior solutions (i.e., vehicle scheduling schemes). These points together form the Pareto frontier, which represents the trade-off relationship between carbon emissions and customer satisfaction.

Figure 8a contains 98 sets of Pareto frontier solutions, and (b) contains 100 sets. Based on the tendencies towards the two objective functions, 10 sets of different objective function values are extracted, as shown in Table 11. The table shows that within the traditional logistics model solutions, Scheme 1 has the lowest carbon emissions, amounting to 7282.64 kg, with a customer satisfaction rate of 91.04%. Scheme 10 achieves the highest customer satisfaction rate at 98.07%, with carbon emissions totaling 8236.56 kg.

Comparing the two logistics models, it is found that the range of fluctuation for both carbon emissions and satisfaction in the JIT logistics model is greater than that in the traditional logistics model. Analysis of different optimization schemes shows that when managers have high requirements for reducing carbon emissions, on one hand, the proposed JIT logistics model, which needs to meet the delivery time window requirements of prefabricated components and the connection requirements between transport vehicles, will sacrifice the smoothness of vehicle connections to reduce carbon emissions, leading to “work idling” situations and thus lower satisfaction. On the other hand, the proposed JIT logistics model can effectively connect the construction and transportation phases, thus increasing the effective utilization rate of related hoisting equipment such as tower cranes, and consequently reducing carbon emissions. When managers have higher requirements for customer satisfaction, compared to traditional logistics model, the proposed JIT logistics model involves transportation vehicles in the hoisting process, increasing the utilization time of transportation vehicles, additionally, the proposed model considers hoisting uncertainty factors and vehicle connection satisfaction, resulting in a significant increase in carbon emissions and lower maximum satisfaction compared to traditional logistics model.

Algorithm performance analysis

The performance of algorithms is typically assessed based on two main factors: the consumption of resources for solving and the quality of the solution. In this study, the optimized number of iterations is utilized as an alternative for evaluating the consumption of resources in solution-finding; the quality of the solutions is appraised from aspects such as the coverage and dominance relationships of the Pareto frontier solutions, and the diversity of the solutions.

In this section, the Pareto frontiers for two logistics models were obtained using both the classical NSGA-II algorithm and the improved NSGA-II algorithm, as illustrated in Fig. 9. The graphical representation indicates that, for both logistics models, the distribution breadth and uniformity of the Pareto frontier derived from the improved NSGA-II algorithm are superior to those obtained from the classical NSGA-II. This suggests that the improved algorithm provides a greater diversity of solutions. Furthermore, the Pareto frontier solutions of the improved NSGA-II can cover and dominate the solution set of the classical algorithm, demonstrating greater algorithmic depth and solving capability. Figure 10 illustrates the variation in the two objective function values—customer satisfaction and logistics carbon emissions—with the number of iterations for both logistics modes. The improved NSGA-II algorithm shows advantages in computational speed, accuracy, and depth, achieving better solutions in less time for the same problem, with faster convergence and stronger optimization capabilities.

In addition, the improved NSGA-II algorithm was compared with MOPSO algorithm for Pareto optimization, and the results were shown in Fig. 11. MOPSO algorithm is a multi-objective optimization algorithm proposed by Coello et al. based on particle swarm optimization algorithm. It can be seen that the improved NSGA-II algorithm retains the advantage of distribution uniformity of GA algorithm, and the calculation quality is better than MOPSO algorithm which also solves multi-objective optimization problems.

Significance of the study

The findings of this study hold broad applicability in prefabricated construction, benefiting multiple key stakeholders. First, project managers and schedulers can leverage the optimized vehicle scheduling scheme to allocate resources more efficiently, reducing time and spatial wastage due to waiting and accumulation. This optimized scheme is particularly beneficial in densely built environments, where it can effectively alleviate site congestion issues. Secondly, logistics and supply chain managers operating under the JIT logistics model can develop flexible scheduling plans tailored to different prefabricated components and transport combinations, aligning with construction progress. This adaptability helps mitigate uncertainties caused by uncontrollable factors like urban traffic and weather, thereby minimizing the cost increases associated with delays. Additionally, construction companies benefit from the proposed optimization method by improving coordination in construction and logistics processes, reducing resource wastage and high secondary handling costs stemming from uncertainties. These improvements bolster the companies’ green brand image and competitive edge.

From a management impact perspective, the multi-objective optimization model developed in this study enhances decision-making accuracy in prefabricated construction projects, facilitating efficient transportation within designated time windows under the JIT logistics model. With the improved NSGA-II algorithm, managers can dynamically adjust vehicle schedules to accommodate real-time changes in construction progress and road conditions, significantly increasing efficiency and resilience in the logistics phase. Furthermore, this optimization model guides managers in balancing customer satisfaction with carbon emissions, ensuring timely delivery while minimizing environmental impact, which supports construction companies’ sustainable development goals. This scheduling optimization approach addresses the traditional scheduling limitations in time coordination and resource allocation and enables companies to gradually achieve cost reduction and efficiency enhancement in logistics management.

Conclusions

This study summarizes the existing problems in the logistics of prefabricated components in prefabricated construction. Clearly, there is a low level of coordination among the various stages of prefabricated component logistics, facing challenges from uncertainty factors. Although the JIT strategy has been applied to plan the component supply chain, the optimization process in existing studies is not thorough enough, failing to consider each individual component in each batch. To address these issues, this study attempts to establish a dual-objective optimization model for prefabricated component logistics under the JIT logistics mode, considering both on-site and off-site logistics, as well as uncertainty factors, to obtain a vehicle scheduling scheme that meets multiple objectives. Furthermore, this study deepens the connotation of the JIT mode by refining the model to the transportation of each transport vehicle and the hoisting of each prefabricated component. To solve the model, an improved NSGA-II algorithm is proposed, which enhances the local search capability, convergence speed, and solution depth of the original algorithm. Subsequent case validation and sensitivity analysis were conducted. The sensitivity analysis indicates that, compared to the traditional logistics model, the proposed JIT logistics model exhibits greater resilience to time uncertainty caused by traffic congestion. The optimization model effectively mitigates the negative impact of uncertainty factors on customer satisfaction and carbon emissions. This study provides a reference for resolving spatial congestion issues in construction projects and offers effective vehicle scheduling solutions for managers.

In the logistics process of prefabricated components, future research can focus on addressing uncertainties and developing a more cohesive supply chain coordination mechanism. The specific directions are as follows:

-

1.

In-depth Exploration of Uncertainty in Logistics Processes: While this study accounts for uncertainties in transportation and installation times within the mathematical model, limitations exist in the quantification of these uncertainties. Future research can further delve into various uncertainty factors throughout the logistics process, including but not limited to weather changes, traffic conditions, construction efficiency, and supply chain fluctuations. A more comprehensive understanding of these variables can help refine logistics models to improve resilience and accuracy under dynamic conditions.

-

2.

Systematic Investigation of Prefabricated Component Supply Chain Coordination Mechanisms: As the industry evolves, the JIT transport model is increasingly replacing traditional transport methods. This shift necessitates well-coordinated collaboration between suppliers, third-party logistics (when applicable), and construction projects. Future research should systematically examine the mechanisms for establishing seamless integration across these stakeholders to enhance responsiveness and efficiency, fostering a fully synchronized prefabricated component logistics supply chain.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Nasirian, A. et al. Optimal work assignment to multiskilled resources in prefabricated construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 145(4), 04019011 (2019).

Han, Y., Yan, X. & Piroozfar, P. An overall review of research on prefabricated construction supply chain management. Eng. Constr. Architectural Manage. 30(10), 5160–5195 (2023).

Tang, X., Xu, P. & Cui, S. Applying the bi-level programming model based on time satisfaction to optimize transportation scheduling of prefabricated components. In 2019 8th International Conference on Industrial Technology and Management (ICITM). 280–284 (IEEE, 2019).

Luo, L. et al. Supply chain management for prefabricated building projects in Hong Kong. J. Manag. Eng. 36(2), 05020001 (2020).

Pheng, L. S. & Chuan, C. J. Just-in-time management of precast concrete components. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 127(6), 494–501 (2001).

Lu, W. & Yuan, H. Investigating waste reduction potential in the upstream processes of offshore prefabrication construction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 28, 804–811 (2013).

Zhang, H. & Yu, L. Dynamic transportation planning for prefabricated component supply chain. Eng. Constr. Architectural Manage. 27(9), 2553–2576 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Digital twin-enabled smart modular integrated construction system for on-site assembly. Comput. Ind. 136, 103594 (2022).

Teng, Y. et al. Reducing building life cycle carbon emissions through prefabrication: evidence from and gaps in empirical studies. Build. Environ. 132, 125–136 (2018).

Cao, X., Miao, C. Q. & Pan, H. T. Comparative analysis and research on carbon emission of prefabricated concrete and cast-in-place buildings based on carbon emission model. Building Struct. 51, 1233–1237 (2021).

Mao, C. et al. Comparative study of greenhouse gas emissions between off-site prefabrication and conventional construction methods: two case studies of residential projects. Energy Build. 66, 165–176 (2013).

Iijima, M., Komatsu, S. & Katoh, S. Hybrid just-in-time logistics systems and information networks for effective management in perishable food industries. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 44(1–2), 97–103 (1996).

Dell’Amico, M., Fischetti, M. & Toth, P. Heuristic algorithms for the multiple depot vehicle scheduling problem. Manage. Sci. 39(1), 115–125 (1993).

Li, W. et al. An improved iterated greedy algorithm for distributed robotic flowshop scheduling with order constraints. Comput. Ind. Eng. 164, 107907 (2022).

Hyun, H. et al. Multiobjective optimization for modular unit production lines focusing on crew allocation and production performance. Autom. Constr. 125, 103581 (2021).

Abido, M. A. & Elazouni, A. Modified multi-objective evolutionary programming algorithm for solving project scheduling problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 183, 115338 (2021).

Chaturvedi, S. et al. Application of PSO and GA stochastic algorithms to select optimum building envelope and air conditioner size-A case of a residential building prototype. Mater. Today Proc. 57, 49–56 (2022).

Faghihi, V., Reinschmidt, K. F. & Kang, J. H. Construction scheduling using genetic algorithm based on building information model. Expert Syst. Appl. 41(16), 7565–7578 (2014).

Razkenari, M. A. et al. A systematic review of applied information systems in industrialized construction. In Construction Research Congress 2018. 101–110 (American Society of Civil Engineers, 2018)

Hasim, S. et al. The material supply chain management in a construction project: A current scenario in the procurement process. 020049 (Advances in Civil Engineering and Science Technology, 2018).

Xun, Z., Kang, L. & Zhao, Z. Construction of prefabricated building supply chain operation model based on SCOR. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 490, 062034 (2019).

Yang, H. et al. Ordering strategy analysis of prefabricated component manufacturer in construction supply chain. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 1–16 (2018).

Hsu, P. Y., Aurisicchio, M. & Angeloudis, P. Establishing Outsourcing and Supply Chain Plans for Prefabricated Construction Projects Under Uncertain Productivity, 529–543 (2017).

Muñuzuri, J. et al. Estimating the extra costs imposed on delivery vehicles using access time windows in a city. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 41, 262–275 (2013).

Ren, M. et al. Design and optimization of underground logistics transportation networks. IEEE Access. 7, 83384–83395 (2019).

Wang, W., Chen, J. C. & Wu, Y. J. The prediction of freeway traffic conditions for logistics systems. IEEE Access. 7, 138056–138061 (2019).

Demir, E. et al. Green intermodal freight transportation: bi-objective modelling and analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res. 57(19), 6162–6180 (2019).

Xu, J. & Hancock, K. L. Enterprise-wide freight simulation in an integrated logistics and transportation system. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 5(4), 342–346 (2004).

Zhong, R. Y. et al. Prefabricated construction enabled by the internet-of-things. Autom. Constr. 76, 59–70 (2017).

Xin, Y. & Ke, J. Research and development of PC building’s management information GDAD-PCMIS system based on BIM. J. Inform. Technologyin Civil Eng. Archit. 9(3), 18–24 (2017).

Wang, D., Luo, J. & Wang, Y. Multifactor Uncertainty Analysis of Prefabricated Building Supply Chain: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 2022).

Kim, T., Kim, Y. & Cho, H. Dynamic production scheduling model under due date uncertainty in precast concrete construction. J. Clean. Prod. 257, 120527 (2020).

Zhai, Y. et al. Multi-period hedging and coordination in a prefabricated construction supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 57(7), 1949–1971 (2019).

Luo, L. et al. Stakeholder-associated supply chain risks and their interactions in a prefabricated building project in Hong Kong. J. Manag. Eng. 35(2), 05018015 (2019).

Hawarneh, A. A., Bendak, S. & Ghanim, F. Construction site layout planning problem: past, present and future. Expert Syst. Appl. 168, 114247 (2021).

Farmakis, P. M. & Chassiakos, A. P. Genetic algorithm optimization for dynamic construction site layout planning. Organ. Technol. Manage. Construction: Int. J. 10(1), 1655–1664 (2018).

Abotaleb, I., Nassar, K. & Hosny, O. Layout optimization of construction site facilities with dynamic freeform geometric representations. Autom. Constr. 66, 15–28 (2016).

Li, C. Z. et al. An internet of things-enabled BIM platform for on-site assembly services in prefabricated construction. Autom. Constr. 89, 146–161 (2018).

Xu, G. et al. Cloud asset-enabled integrated IoT platform for lean prefabricated construction. Autom. Constr. 93, 123–134 (2018).

Demiralp, G., Guven, G. & Ergen, E. Analyzing the benefits of RFID technology for cost sharing in construction supply chains: a case study on prefabricated precast components. Autom. Constr. 24, 120–129 (2012).

Du, J. et al. Improved biogeography-based optimization algorithm for lean production scheduling of prefabricated components. Eng. Constr. Architectural Manage. 30(4), 1601–1635 (2023).

Oral, E. L., Mıstıkoglu, G. & Erdis, E. JIT in developing countries—a case study of the Turkish prefabrication sector. Build. Environ. 38(6), 853–860 (2003).

Wu, P. & Low, S. P. Applying JIT principles to reduce carbon emissions in precast concrete industry. In Proceedings of CRIOCM 2008: Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, 281–284 (2008).

Ko, C. H. & Wang, S. F. GA-based decision support systems for precast production planning. Autom. Constr. 19(7), 907–916 (2010).

Wang, Z. & Hu, H. Improved precast production–scheduling model considering the whole supply chain. J. Comput. Civil Eng. 31(4), 04017013 (2017).

Kong, L. et al. Sustainable performance of just-in-time (JIT) management in time-dependent batch delivery scheduling of precast construction. J. Clean. Prod. 193, 684–701 (2018).

Wang, Z., Hu, H. & Gong, J. Framework for modeling operational uncertainty to optimize offsite production scheduling of precast components. Autom. Constr. 86, 69–80 (2018).

Hsu, P. Y., Angeloudis, P. & Aurisicchio, M. Optimal logistics planning for modular construction using two-stage stochastic programming. Autom. Constr. 94, 47–61 (2018).

Salari, S. A. S. et al. Off-site construction three-Echelon supply chain management with stochastic constraints: a modelling approach. Buildings 12(2), 119 (2022).

Hsu, P. Y., Aurisicchio, M. & Angeloudis, P. Risk-averse supply chain for modular construction projects. Autom. Constr. 106, 102898 (2019).

Jaśkowski, P., Sobotka, A. & Czarnigowska, A. Decision model for planning material supply channels in construction. Autom. Constr. 90, 235–242 (2018).

Almashaqbeh, M. & El-Rayes, K. Minimizing transportation cost of prefabricated modules in modular construction projects. Eng. Constr. Architectural Manage. 29(10), 3847–3867 (2022).

Liu, J., Soleimanifar, M. & Lu, M. Resource-loaded piping spool fabrication scheduling: material-supply-driven optimization. Visualization Eng. 5, 1–14 (2017).

Fang, Y. & Ng, S. T. Genetic algorithm for determining the construction logistics of precast components. Eng. Constr. Architectural Manage. 26(10), 2289–2306 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Meta-heuristic algorithm for solving vehicle routing problems with time windows and synchronized visit constraints in prefabricated systems. J. Clean. Prod. 250, 119464 (2020).

Qiu, S. H., Chen, S. D. & Wang, Y. X. The application of genetic algorithm on workshop facilities optimal layout. Mach. Des. Manuf. Eng. 46(2), 80–83 (2017).

Srinivas, N. & Deb, K. Muiltiobjective optimization using nondominated sorting in genetic algorithms. Evolution. Comput. 2(3), 221–248 (1994).

Deb, K. et al. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 6(2), 182–197 (2002).

Eggleston, H. S. et al. 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories. (2006).

Funding

This work was supported by the Construction Science and Technology Plan Project of Chongqing (Project No. Construction and Scientific 2023 Project No.2 − 1), the Youth Project of Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Education Commission of China (Project No. KJQN202304302), and the Science and Technology Innovation Project in the Field of Housing and Urban Rural Construction in Sichuan Province (Project No. SCJSKJ2022-27).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Z. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, and provided the software. J.J. curated the data and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. C.X. conducted the formal analysis and validation. Y.F. reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.L. carried out the investigation and provided resources. P.D. administered the project. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Jiang, J., Xia, C. et al. Dual-objective optimization of prefabricated component logistics based on JIT strategy. Sci Rep 14, 31267 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82689-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82689-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multi-objective risk optimization for sustainable modular infrastructure using machine learning and metaheuristics

Asian Journal of Civil Engineering (2025)