Abstract

Testicular cancer predominantly affects adolescents and young adults (AYAs) aged 15–39 years. This study analyzed the global, regional, and national burden of testicular cancer among AYAs (1990 to 2021). Data from the Global Burden of Disease study was used to calculate age-standardized rates of incidence (ASIR), prevalence (ASPR), and disability-adjusted life years (ASDR). Trends were assessed using the Joinpoint regression and Bayesian age-period-cohort models, with projections up to 2035. Results showed the global ASIR of 4.05 (95% CI: 3.80–4.35), ASPR of 31.05 (95% CI: 28.88–33.68), and ASDR of 24.82 (95% CI: 22.99–26.91) per 100,000 in 2021, respectively. From 1990 to 2021, ASIR and ASPR increased, while ASDR remained relatively stable. Significant geographical disparities were observed, with Europe and Latin America showing higher burdens compared to Asia and Africa. The 25–29 age group had the highest age-specific rate of incidence (5.58; 95% UI: 5.25–5.97) and disability-adjusted life years (34.09; 95% UI: 31.55–37.11) per 100,000, while the 30–34 age group had the highest age-specific prevalence rate (43.12; 95% UI: 40.51–46.56) per 100,000 in 2021. By 2035, the global numbers of incidence and prevalence cases were projected to increase, with DALYs and age-standardized rates declining. These findings are crucial for informing global strategies in testicular cancer prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Testicular cancer (TC) is an uncommon malignancy, accounting for just 1% of adult cancers and 5% of urological cancers1. Despite this, it is the leading cancer among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) aged 15–39 years2,3. In the histological classification of TC, testicular germ cell tumors make up around 98%, with seminomas being the most common at 50–60%, followed by non-seminomas at 40–50%, and spermatocytic tumors at less than 1%4,5. The mechanisms underlying the development of TC are not entirely elucidated. Associated risk factors may include cryptorchidism, a familial predisposition to testicular cancer, hypospadias, and a reduced sperm count4,5.

In the past half-century, the management of germ cell tumors has seen substantial progress, with survival rates for advanced cases escalating from around 25% in the 1970s to almost 80% currently3. Despite these advancements, the global incidence of TC has witnessed a notable rise, increasing from 1.9 cases per 100,000 population in 1990 (95% uncertainty interval [UI]: 1.6–2.2) to 2.8 in 2021 (95% UI: 2.4–3.3)6, which positions it a significant public health concern globally. Current studies on the burden of testicular cancer predominantly focus on the general population6,7,8, with limited research on adolescents and young adults aged 15–39 years, who are at the highest risk. This age group plays a vital role in socioeconomic activities and contributes substantially to future population growth. Failure to control and prevent the disease could increase the burden on patients and have long-term adverse effects on societal productivity and demographic trends. Moreover, TC has a profound impact on the fertility, psychological health, and overall quality of life of young patients. Studies have shown that survivors frequently face challenges such as fertility issues9, sexual dysfunction10,11,12, and psychological stress12,13, particularly among younger patients. Therefore, it is essential to study the burden of TC in AYAs for understanding the epidemiology of the disease and developing targeted prevention and treatment strategies that can improve patient outcomes and enhance quality of life.

In conclusion, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study has become an essential tool for understanding and evaluating the global burden of diseases14,15,16. It offers comprehensive data across time periods, regions, and age groups on various metrics such as incidence, prevalence, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)17. By utilizing the latest data from GBD 2021, our secondary research focused on the adolescent and young adult population, systematically analyzing the incidence, prevalence, and DALYs of TC at global, regional, and national levels. The study aims to provide new perspectives on the global burden and trends of TC in this age group and offers scientific evidence for public health policy development, thereby advancing global health initiatives.

Methods

The GBD 2021 Study, conducted by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), represents the most comprehensive effort to date in measuring global epidemiological levels and trends. It covers 21 GBD regions and 204 countries/territories, examining 371 diseases, 288 causes of death, and 88 risk factors from 1990 to 202114,15. The methodology employed in the GBD 2021 has been refined in each cycle and was thoroughly documented in prior research14,15,17. Detailed results from the GBD 2021 study, including estimates for all diseases and injuries analyzed, are accessible through the Global Health Data Exchange platform (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/).

Data source

The diagnosis of TC in this study was strictly aligned with the clinical criteria and classifications prescribed by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)14, including ICD-10 (C62-C62.9, D29.2-D29.8, D40.1-D40.8) and ICD-9 (186-186.9, 222.0, 222.3, 236.4). In addition, our study focused on three major metrics: incidence, prevalence, and DALYs associated with TC, and corresponding age-standardized rates. Location search parameters were global, Socio-Demographic Index regions, Global Burden of Disease (GBD) regions, and 204 countries/territories. Based on epidemiological homogeneity and geographic contiguity, the GBD study organized 204 countries and territories into 21 GBD regions, allowing for more detailed subgroup analyses18. Throughout the process, our study strictly followed the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Assessment Reporting (GATHER)19 (Table S1).

Socio-demographic index

The Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) is an essential tool for assessing socio-economic development20,21. The score, ranging from 0 to 1, is derived from a combination of per capita income, education, and fertility rates. This index categorizes regions into quintiles, from low to high, with the intervals for each quintile defined as: Low SDI, Low-middle SDI, Middle SDI, High-middle SDI and High SDI (Table S2). Higher SDI values indicate better socio-economic conditions. In this study, the SDI was employed to explore the relationship between socio-economic status and disease burden, highlighting health disparities. Tables S3, S4 provide a detailed distribution of SDI quintiles across regions and locations.

Statistical analysis

To standardize statistical indicators, we calculated the age-standardized rate (ASR) using age-specific weights (Table S5), detailed by the subsequent formula (1)22,23,24:

(N represents the collective age groups, with i index the ith group. αi is the rate specific to age group i, and Wi denotes the individuals in the standard population for that group24).

(y represents the age-standardized rate, and x represents the calendar year of ASR, β1 represents the regression coefficient)

(wi in the formula denotes the width of each segment function interval [number of years], and βi corresponds to the regression coefficient for each interval.)

Using Joinpoint regression software25, we calculated annual percentage change (APC) (formula 2) and average annual percentage change (AAPC) (formula 3) for ASRs with trends categorized by their 95% CI relative to zero26,27. Using a grid search method, we identified joinpoints within the time series data of ASRs, while the significance of these points was evaluated through Monte Carlo permutation tests. Joinpoints typically signify notable shifts in trends or slopes, offering a systematic mean to quantify and describe the dynamics of data trends over time. Furthermore, in order to highlight the temporal discrepancies and trends in global ASRs, we conducted an in-depth comparison of the AAPCs for the periods of 1990 to 1999, 2000 to 2009, 2010 to 2019, the COVID-19 period of 2019 to 2021, and the overall period from 1990 to 2021.

Decomposition analysis28,29 was performed to quantify the contributions of population aging, population growth, and epidemiologic changes to TC in AYAs from 1990 to 2021. Smoothing splines models assessed the relationship between the ASRs of TC and the SDI in 21 GBD regions and 204 countries/territories, and Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was conducted to calculate the r indices and p-values.

Frontier analysis was conducted to investigate the link between disease burden and sociodemographic development. This method, which integrated ASDR and the SDI, enabled us to model the minimum expected disease burden achievable at a given developmental level across 204 countries/territories30,31. Following the methodologies established in previous research30,31, we applied data envelopment analysis (DEA) under the free disposal hull (FDH) model to outline nonlinear boundaries with data from 1990 to 2021. Uncertainty was managed using 100 bootstrap samples, which involved random resampling with replacement from all countries and territories for every year. Subsequently, the average frontier at each SDI value was computed from these samples, and then Loess regression with a local polynomial number of 1 and a span of 0.2 was applied to smooth the frontier. Countries exhibiting super-efficiency were removed from the frontier to mitigate outlier influence. This analysis quantified the extent of unrealized health benefits by comparing current DALYs with the frontier, referred to as the effective difference. Such insights are instrumental in guiding effective interventions tailored to the specific developmental context of each country or region.

Many models have been applied to forecast the burden of diseases, including Nordpred models, Joinpoint models, and Bayesian age-period-cohort (BAPC) model. The BAPC model integrates the sample information and priori information to estimate the posterior information, which is then used to infer unknown parameters. Due to the continuity effect of adjacent time, the model uses second-order random walk to smooth the prior distributions of age, period, and cohort effects, enhancing the reliability of predictions. Additionally, it employs the Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (INLA) algorithm to directly approximate the posterior marginal distributions, without the need to address the mixing and convergence issues prevalent in conventional Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo methods32,33. As previous studies have shown, the BAPC model demonstrates a relatively lower error compared to other models34. Utilizing TC data (1990–2021), along with historical (1990–2021) and projected (2022–2035) population data and world population age-standard data from the GBD database16,35,36, we forecasted disease burdens from 2022 to 2035 using the R packages BAPC (v0.0.36) and INLA (v23.04.24).

The statistical analyses were performed using R (v4.4.1) and the Joinpoint Regression Program25 (v5.1.0.0), with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Ethics statement

No ethical approval was necessary for this investigation, which utilized the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) database—a publicly available dataset with anonymized participant data.

Results

Global level

Globally, there were 61,596 (95% uncertainty interval [UI]: 57,749–66,175) incidence cases of TC among AYAs in 2021, with ASIR of 4.05 (95% CI: 3.80–4.35) per 100,000 population, which represented an increase since 1990 of 2.64 (95% CI: 2.50–2.79) per 100,000 population (AAPC: 1.37, 95% CI: 0.99 to 1.76) (Table 1, and Figs. 1 and 2). The global ASIR exhibited significant upward trends from 1990 to 1999, 2000 to 2009, and 2010 to 2019, with the fastest rise from 2010 to 2019 (AAPC: 1.88, 95% CI: 1.75 to 2.01) (Table S6). However, from 2019 to 2021, the AAPC p-value was 0.6706, indicating no significant change in global ASIR. Joinpoint regression revealed four distinct points—1993, 1997, 2002, and 2019—when there were significant changes in TC incidence (Fig. 1). Moreover, there were 472,966 (95% UI: 440,012–512,848) prevalence cases of TC among AYAs in 2021, with ASPR of 31.05 (95% CI: 28.88–33.68) per 100,000 population, which also represented an increase since 1990 (AAPC: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.96) (Table 2, and Figs. 1 and 2). During 1990–1999, 2000–2009, and 2010–2019, the global ASPR exhibited similar growth patterns (AAPCs: 1.68–1.80, all p < 0.05). The AAPC value for the period 2019–2021 was − 0.72, but the p-value was 0.7010, indicating a stable trend (Table S6). Utilizing Joinpoint regression, notable prevalence variations of TC were identified at five specific years: 1993, 1997, 2003, 2007, and 2019. In addition, there were 376,564 (95% UI: 348,929–408,401) cases of DALYs in 2021, and the ASDR was 24.82 (95% CI: 22.99–26.91) per 100,000 population (Table 3, and Figs. 1 and 2). However, ASDR exhibited significant fluctuations, with significant decreases from 1990 to 1999 and 2000 to 2009, and a significant increase from 2010 to 2019 (Table S6). The overall trend of ASDR from 1990 to 2021 remained stable, with a p-value of 0.0555, indicating no significant change. Overall, from 1990 to 2021, the AAPCs of ASIR and ASPR in TC among AYAs continued to increase globally, while the AAPC of ASDR showed an irregularly shaped trend, gradually declining from 1990 to 2007, gradually increasing after 2007, and finally peaking in 2019 (Fig. 1).

Joinpoint regression analysis of ASIR, ASPR, and ASDR of testicular cancer in adolescents and young adults in global from 1990 to 2021. (a) Age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR); (b) Age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR); (c) Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years rate (ASDR). * Indicates that the Annual Percent Change (APC) is significantly different from zero at the alpha = 0.05 level.

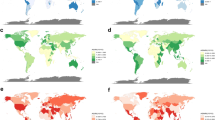

Age-standardized rates in 1990 and 2021, and their AAPCs from 1990 to 2021 for testicular cancer among adolescents and young adults at the global, 5 SDI regional, and 21 GBD regional levels. (a) AAPC of ASIR; (b) ASIR in 1990 and 2021; (c) AAPC of ASPR; (d) ASPR in 1990 and 2021; (e) AAPC of ASDR; (f) ASDR in 1990 and 2021. ASIR, age-standardized incidence rate; ASPR, age-standardized prevalence rate; ASDR, age-standardized DALYs rate; DALYs, disability-adjusted life-years. AAPC, average annual percentage change. GBD regions are arranged from left to right based on SDI values, with lower values on the right.

SDI level

Between 1990 and 2021, the ASIR and ASPR for TC in AYAs rose across all SDI regions, with Middle SDI regions demonstrating the steepest increase in ASIR (AAPC: 4.37, 95% CI: 4.10 to 4.65) and in ASPR (AAPC: 6.61, 95% CI: 6.40 to 6.83) (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 2). Despite the slowest growth in ASIR and ASPR from 1990 to 2021, the High SDI region still recorded the greatest number of incidence cases (21,798; 95% CI: 20,201–23,544), the highest ASIR (11.38; 95% CI: 10.55–12.3/ 100,000 population), the largest number of prevalence cases (198,512; 95% UI: 184,139–214,886), and the highest ASPR (103.70; 95% CI: 96.22–112.30/ 100,000 population) in 2021. Interestingly, the High SDI regions exhibited a sustained increase in ASIR and ASPR between 1990 and 2021, alongside a decline in ASDR (Fig. 2). Figure S1 reveals periods of stability for ASIR and ASPR from 1997 to 2003 and 2009 to 2012, with a stable for ASDR from 2013 to the present. Additionally, the Middle SDI region demonstrated the most significant increase in ASDR, and particularly between 2010 and 2019 (APC: 2.77, 95% CI: 2.53–3.01). This resulted in the largest DALYs burden (126,951; 95% UI: 115,969–138,193) and the highest ASDR (26.74; 95% CI: 24.43–29.08/ 100,000 population) in 2021 (Table 3; Fig. 2). Furthermore, the ASDR remained stable in the Low SDI regions, with P-values indicating no significant alterations at 0.0650. Concurrently, the Low SDI region experienced the lowest ASRs and case numbers across incidence, prevalence, and DALYs in 2021. In summary, the disease burden of TC among AYAs across the five SDI regions exhibited significant temporal and geographical disparities from 1990 to 2021.

GBD regional level

Across the 21 GBD regions, the ASIR, ASPR, and ASDR in 2021 were the highest in Southern Latin America, with values of 20.93 (95% CI: 15.86–27.33), 181.03 (95% CI: 130.83–238.04), and 110.66 (95% CI: 88.83–134.71) per 100,000 population, respectively. The second highest ASIR and ASPR was in Central Europe, with the values of 17.18 (95% CI: 14.60–20.16) and 149.50 (95% CI: 124.83–177.26) per 100,000 population. The second highest ASDR was in Central Latin America, with the value of 101.23 (95% CI: 91.27–111.41) per 100,000 population. The lowest ASIR and ASPR were found in Western Sub-Saharan Africa, with values of 0.33 (95% CI: 0.24–0.43), 1.03 (95% CI: 0.60–1.57) per 100,000 population, respectively. The lowest ASDR was found in Oceania (8.01; 95% CI: 5.31–11.67) per 100,000 population (Tables 1, 2 and 3; Fig. 2). Besides, Western Europe reported the greatest numbers of incidence cases (9933; 95% UI: 8623–11,509) and prevalence cases (91,302; 95% UI: 79,230–105,941) in 2021, with South Asia showing the largest number of DALYs (107,816; 95% UI: 88,503–131,204).

From 1990 to 2021, no significant decline was observed in ASIR or ASPR of TC in AYAs across all 21 GBD regions (Fig. 2). Notably, the Caribbean had the greatest increase in ASIR, while three regions—High-income Asia Pacific, Western Europe, and Oceania—demonstrated stability in ASIR (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, Central Latin America experienced the most significant increase in ASPR, with High-income Asia Pacific and Western Europe showing stable trends (Fig. 2). Furthermore, ASDR across the 21 GBD regions demonstrated significant variation, with the Caribbean recording the largest increase and Western Europe the largest decrease (Fig. 2).

National level

In 2021, Monaco exhibited the highest ASIR and ASPR among the 204 countries and territories, at 86.36 (95% CI: 39.00–167.51), and 793.08 (95% CI: 358.35–1536.24) per 100,000 population, respectively (Fig. 3, Tables S8, and S9). Mexico had the highest ASDR (149.33; 95% CI: 133.44–166.20) per 100,000 population. United States of America showed the most incidence cases (7856; 95% UI: 7232–8538) and prevalence cases (71,475; 95% UI: 65,665–77,662) (Tables S8, S9, and Fig. S2). India had the highest number associated DALYs (67,621; 95% UI: 55,897–81,032) (Table S10 and Fig. S2).

Age-standardized rates in 2021, and their AAPCs from 1990 to 2021 for testicular cancer among adolescents and young adults across 204 countries and territories. (a) ASIR with top three countries; (b) AAPC of ASIR with top three countries; (c) ASPR with top three countries; (d) AAPC of ASPR with top three countries; (e) ASDR with top three countries; (f) AAPC of ASDR with top three countries. ASIR age-standardized incidence rate, ASPR age-standardized prevalence rate, ASDR age-standardized DALYs rate, DALYs disability-adjusted life-years, AAPC average annual percentage change.

Among the 204 countries and territories, Puerto Rico had the fastest growing ASIR from 1990 to 2021, with Switzerland showing the largest decline (Fig. 3, Table S8). In addition, Ecuador showed the largest increase in ASPR, with United Kingdom experiencing the largest decrease (Fig. 3, Table S9). Furthermore, Belize exhibited the most significant increase in ASDR, while Luxembourg exhibited the most substantial reduction (Fig. 3 and Table S10).

Relationship between SDI and TC burden

Figure 4 illustrates the correlation between ASRs and the SDI across 21 GBD regions from 1990 to 2021. The results revealed an inverted U-shaped nonlinear relationship between ASIR and SDI, characterized by an initial rise when SDI is below around 0.8, followed by a steep decline when SDI surpasses this level. A similar nonlinear relationship was observed between ASPR and SDI. Meanwhile, the ASDR and SDI exhibited an inverted M-shaped curve, with a peak at an SDI of around 0.75 and a subsequent rapid decrease. Collectively, these analyses underscore a significant relationship between ASIR (r = 0.82, p < 0.001), ASPR (r = 0.86, p < 0.001), ASDR (r = 0.24, p < 0.001), and SDI.

The association between age-standardized rates of testicular cancer in adolescents and young adults and SDI at 21 GBD regional level from 1990 to 2021. (a) Age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR); (b) Age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR); (c) Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years rate (ASDR). SDI sociodemographic index. Each point represents the SDI and ASRs values for the GBD region from 1990 to 2021.

In 2021, data from 204 countries and territories indicated that the ASIR and ASPR of TC in AYAs were positively associated with the SDI, reflecting an upward trend in the ASIR and ASPR as SDI increased (Fig. S3). Furthermore, Fig. S3 illustrated that the ASDR initially rises with increasing SDI, followed by a gradual decrease at higher levels of SDI.

Decomposition analysis

Investigating the effects of population aging, growth, and epidemiological changes on the burden of TC in AYAs from 1990 to 2021, we conducted a decomposition analysis of incidence, prevalence and DALYs. Globally and all SDI regions, the increase in TC incidence, prevalence and DALYs among AYAs was largely driven by population growth and epidemiological changes over this period. Conversely, in High and High-middle SDI regions, there was a substantial decrease in the overall variation of DALYs (−33.67%; −12.11%), mainly due to epidemiological improvements (−37.72%; −15.27%). Additionally, in low SDI regions, the influence of population growth on the rise in incidence and DALYs was particularly significant (186.04%, 146.63%). Among the 21 GBD regions, Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa experienced the highest contributions from population growth, with increases of 233.53% in incidence, 477.95% in prevalence and 181.75% in DALYs. Meanwhile, Caribbean recorded the highest impact of epidemiological changes, with incidence and DALYs up by 589.54% and 218.79%, respectively, while prevalence soared by 1895.06% in Andean Latin America. Overall, the contribution of population aging to the overall burden of TC in AYAs was relatively minor compared with the impacts of population growth and epidemiological changes (Fig. 5 and Table S11).

Changes in incidence, prevalence, and DALYs of testicular cancer in adolescents and young adults according to the determinants at the population level of population growth, aging, and epidemiological changes from 1990 to 2021. (a) At global, SDI regional level. (b) At GBD regional level. DALYs disability-adjusted life-years, SDI sociodemographic index. Black dots indicate overall percent difference, representing the percent difference in the numbers of incidence, prevalence, and DALYs between 1990 and 2021 (overall percent difference = [numbers2021−numbers1990]/numbers1990*100%). GBD regions are arranged from top to bottom based on SDI values, with lower values at the bottom.

Frontier analysis

To gain insights into the potential to reduce DALYs rate of TC in AYAs relative to a country’s developmental status, we conducted a frontier analysis using data on ASDR and the SDI from 1990 to 2021. The top 15 countries demonstrating the most significant effective differences from the frontier (ranging from 67.95 to 148.83) included Mexico, Monaco, Chile, Bulgaria, Uruguay, Argentina, Zambia, Montenegro, Hungary, Poland, North Macedonia, Costa Rica, Slovakia, Bolivia (Plurinational State of), and Georgia (identified by black labels). Conversely, the 10 countries with the lowest ASDR, considering their developmental status and hence the smallest effective differences (ranging from 0 to 2.67), included Palau, Niger, Tajikistan, Nigeria, American Samoa, Morocco, Cabo Verde, Somalia, Dominican Republic, and Oman. As shown in Fig. 6, countries and territories with low SDI (< 0.466) and low effective differences, such as Niger, Somalia, Papua New Guinea, Yemen, and Solomon Islands, were indicated with blue labels. Meanwhile, countries and territories with high SDI (> 0.810) and notable developmental differences, including Monaco, Poland, Slovakia, Czechia, and Puerto Rico, were marked with red labels (Table S12).

Frontier analysis on the basis of sociodemographic-index and age-standardized DALYs rate for testicular cancer in adolescents and young adults across 204 countries and territories. (a) ASDR of 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2021. (b) ASDR of 204 countries and territories in 2021. Cyan dots indicate a decrease in ASDR between 1990 and 2021; Coral color dots indicate an increase in ASDR from 1990 to 2021. ASDR age-standardized DALYs rate, DALYs disability-adjusted life-years, SDI sociodemographic-index.

Age patterns

In 2021, the global incidence cases were 4237 (95% UI: 3912–4643) for those aged 15 to19 years, 11,323 (95% UI: 10,593–12,284) for those aged 20 to 24 years, 16,601 (95% UI: 15,605–17,748) for those aged 25 to 29 years, 16,312 (95% UI: 15,329–17,536) for those aged 30 to 34 years, and 13,121 (95% UI: 12,309–13,964) for those aged 35 to 39 years(Table S13). The highest incidence cases and age-specific incidence rate was recorded in the 25 to 29 years age group, which also showed the highest DALYs and age-specific DALYs rate (Fig. S4 and Table S13). Conversely, the highest prevalence cases and age-specific prevalence rates were observed in the 30 to 34 years age group (Fig. S4 and Table S13). As shown in Fig. S4, the disease burden of TC was predominantly concentrated in the 25–29 and 30–34 age groups from 1990 to 2021. Across SDI regions, the 25–29 years age group in High SDI regions demonstrated the highest age-specific incidence and prevalence rates, as well as the highest absolute number of incidence and prevalence cases (Fig. S5). In contrast, the highest number of DALYs and age-specific DALY rate were recorded in the 25–29 years age group at Middle SDI regions (Fig. S5). Among GBD regions, the 25–29 years age group in Southern Latin America exhibited the highest rates of age-specific incidence, prevalence, and DALYs, and this age group in High-income North America recorded the greatest absolute numbers of both incidence and prevalence cases (Fig. S6). Furthermore, the 25–29 years age group in South Asia accounted for the highest absolute number of DALYs. From 1990 to 2021, the age-specific incidence and prevalence rates of TC among AYAs increased across all age groups, with the greatest increase observed in the 20–24 years age group (Table S13 and Fig. S7). Over the same period, the age-specific DALY rate for TC either decreased or remained stable in all age groups, except for the 20–24 years age group, which saw a slight increase (Table S13 and Fig. S7).

Prediction analysis of testicular cancer in AYAs till 2035

The BAPC model was applied to estimate the future burden of TC in AYAs from 2022 to 2035. The model projected an increase in the number of incidence cases to 66,188 by 2035 from 61,585 in 2021, and the number of prevalence cases to 513,978 by 2035 from 472,953 in 2021 (Fig. 7, Table S14). Additionally, the DALYs were projected to decrease from 376,618 in 2021 to 360,086 by 2035 over the same period. Furthermore, the results indicated a slight decrease in ASIR from 4.05 per 100,000 population in 2021 to 3.78 per 100,000 population in 2035, along with a reduction in ASPR from 31.05 per 100,000 population in 2021 to 28.56 per 100,000 population in 2035, and a drop in ASDR from 24.82 per 100,000 population in 2021 to 21.29 per 100,000 population in 2035 (Fig. 7, Table S14).

Trends of numbers and age-standardized rates for testicular cancer among adolescents and young adults from 1990 to 2035 at global level predicted by BAPC models. (a) Numbers of incidence; (b) Age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR); (c) Numbers of prevalence; (d) Age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR); (e) Numbers of DALYs; (f) Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years rate (ASDR). SDI sociodemographic index, BAPC Bayesian age-period-cohort.

Discussion

Given the high incidence of TC among AYAs aged 15–393, this study, to our knowledge, is the first to focus on the adolescent population. By employing decomposition analysis, frontier analysis, and the BAPC model, we comprehensively evaluated the global, regional, and national burden and trends of TC in AYAs. Compared to previous GBD studies7,8,37, our research’s primary contribution was the use of the latest 2021 GBD database and a specific focus on the high-incidence adolescent group. Additionally, we projected the global incidence, prevalence, and DALYs up to 2035, aiming to provide a more comprehensive understanding of disease trends. In this study, we revealed several critical findings: (1) From 1990 to 2021, there has been a steady increase in the number of TC incidence, prevalence, and DALYs among AYAs globally. In addition to the relative stability of ASDR in TC among AYAs, the ASIR and ASPR were also gradually increasing from 1990 to 2021. However, a decreasing trend of ASDR was observed in High-SDI and High-middle SDI regions. (2) Significant disparities in the burden of TC persisted across regions, and the contributions of population aging, growth, and changes in epidemiology varied significantly. (3) Among the five age groups, the 25–29 and 30–34 age groups bore a higher disease burden of TC. (4) Between 2022 and 2035, the global ASIR, ASPR, ASDR, and DALYs for TC in AYAs were projected to show a slight decrease. Nevertheless, the total number of incident cases and prevalent cases was anticipated to increase.

An in-depth analysis of the GBD database 2021 indicated a notable increase in the ASIR and ASDR of TC among AYAs worldwide from 1990 to 2021. This is consistent with the previous study on the increasing incidence and prevalence in all age groups7. The results of decomposition analysis showed that epidemiological changes being a primary driver, accounting for 64.44% of the incident cases increase and 72.59% of the prevalent cases. Advancements in medical technology, including ultrasound diagnostics, biopsy techniques, and tumor marker assessments, had played a key role in this trend by enhancing early detection. Evidence from numerous studies suggests that MicroRNAs (miRNAs), notably miR-371a-3p, exhibits superior discrimination accuracy in diagnosing, monitoring, and predicting the recurrence of germ cell tumors (GCTs), thereby positioning miRNAs as prospective biomarkers1,38. The widespread adoption of these technologies has facilitated earlier diagnosis, partially explaining the increase in testicular cancer cases. Furthermore, lifestyle changes, and environmental factors might have also contributed to the rising incidence of testicular cancer4,39. These factors may act synergistically to increase risk, contributing to the overall rise in incidence and prevalence. Despite the rising of ASIR and ASPR, the global ASDR for TC among AYAs showed a decline from 1990 to 2007. This reduction was largely attributable to the introduction of cisplatin-based chemotherapy, which significantly enhanced survival outcomes for TC. Additionally, the introduction of a staging system by the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG) in 1997, based on tumor location and serum tumor marker levels, established a standardized framework for diagnosis and treatment40. Technological advancements in imaging, such as the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for detecting brain metastases and FDG-PET for evaluating large residual masses (> 3 cm) following chemotherapy, had also contributed to improvements in testicular cancer management41. However, there has been a sustained increase in the global ASDR since 2007, with particularly notable increases in Low Middle and Middle SDI regions. This trend might be linked to the rapid rise in incidence and prevalence of TC in these regions, exacerbated by a lack of adequate healthcare resources to effectively manage the disease burden. Strengthening healthcare infrastructure, promoting health awareness among adolescents, training healthcare professionals, allocating resources in collaboration with international health organizations and implementing evidence-based guidelines may reduce the disparities in ASDR for TC among AYAs.

At the regional level, our findings revealed significant geographic disparities in the ASRs for TC among AYAs. From 1990 to 2021, regions such as Europe, North America, and Australia maintained relatively high ASIR and ASPR levels. Despite the upward trend in ASIR and ASPR at most regions of Asia and Africa from 1990 to 2021, they remained lower than the global average by 202142. This could be attributed to several factors. First, the relatively high economic status of Europe, North America, and Australia facilitated comprehensive screening, advanced early diagnostic techniques, and well-organized tumor registries. Second, racial disparities are evident in the United States, where the incidence is five times higher among whites than African Americans43. Third, genetic factors account for 37.0–48.9% of the heritable risk of testicular cancer44,45. Fortunately, there has been a reduction in ASDR in regions that have typically exhibited higher ASIR and ASPR. This decline likely reflects the progress made in preventive measures (such as health education and public health campaigns)46and new treatment modalities47,48. Furthermore, ASIR and ASPR had significantly increased in the Caribbean and certain regions in Latin America, with South Latin America surpassing Central Europe as the highest ranked region globally by 202142. Concurrently, the ASDR has also shown varying degrees of increase in GBD regions. Limited data are available on the causes behind the increased ASRs for TC in Caribbean and Latin American regions. Several factors might account for this observation. First, economic shifts in these regions have increased exposure to polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics and heavy metals in occupational and living environments. Second, the 2015 report on drug use in the Americas indicated a growing trend in marijuana consumption among high school students across various Latin American and Caribbean nations49. Take Chile as an example, marijuana use was most common among 20- to 24-year-olds, with a steady rise noted annually50. However, research suggested that individuals with a history of marijuana use are at a higher risk of developing Testicular Germ Cell Tumors (TGCTs) compared to those who have never used the substance51. Furthermore, economic development has potentially strengthened cancer registry systems and diagnostic capabilities, like trans-scrotal ultrasonography and serum tumor markers (AFP, βHCG, and LDH), which may also have contributed to the growing ASIR and ASPR. From 1990 to 2021, significant regional differences in the burden of TC were also observed among the five age groups across SDI regional and GBD regional levels. Nonetheless, the most significant disease burden from TC was found in the 25–29 and 30–34 age groups. These results underscore the need for public health interventions tailored to the distinct characteristics of each age cohort, such as improving lifestyle, staying away from marijuana, increasing health awareness and regular self-examination.

At the national level, it is crucial to focus on the countries with the heaviest TC burden, namely Mexico, Monaco, Chile, and Turkey. Furthermore, we should pay attention to those experiencing the fastest-growing burden, like Puerto Rico, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Belize, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Guyana, and Ecuador, as these may be more vulnerable to the impact of TC due to limited healthcare resources. Obviously, countries and regions from Latin America and the Caribbean exhibited a greater burden of TC among AYAs. As highlighted by The Lancet Commission, improvements are needed in Latin American and Caribbean regions to combat the cancer burden, including more investment in cancer control, expansion of universal health coverage, adequate registries, early diagnosis, and treatment52. The results of frontier analysis indicated that certain countries such as Niger, Somalia, Papua New Guinea, Yemen, and Solomon Islands, despite their low SDI, exhibited the lowest DALY levels for TC in AYAs. This suggested that their burden closely aligned with or even surpassed the best expected performance for their SDI levels. Conversely, some high-SDI countries and territories, such as Monaco, Poland, Czechia, Slovenia, and Puerto Rico, were not meeting expectations. High-income countries might reduce their ASDR through the following strategies: financing newer and more expensive interventions; providing access to genomic testing and advanced pathology services; implementing advanced radiation and surgical techniques; offering costly cancer medications; and developing high-quality oncology delivery systems with the potential to allocate resources according to evidence-based medical53. Nonetheless, further research is needed to identify the factors contributing to the success of high-performing countries/territories and to understand the causes of higher DALYs in lower-performing regions. This may aid in developing targeted strategies and interventions to reduce the global burden of TC in AYAs, thereby enhancing health outcomes and quality of life.

Projections from the BAPC model revealed an opposing trend in the disease burden of TC among AYAs from 2022 to 2035: the absolute numbers of incident cases and prevalent cases were anticipated to rise, concurrent with a projected decrease in DALYs. This trend may be partly attributed to effective public health interventions, and advancements in cancer treatments. Interestingly, the results showed a slight decrease in global ASRs during the same time period. A previous study by Charlotte Le Cornet et al. observed a potential stabilization or decline in incidence rates at historically high-risk regions of Northern and Western Europe in 201054. Additionally, research by Ariana Znaor et al. indicated that incidence rates for TC had peaked in Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, and Austria before 2010, with forecasts for a quarter of European countries showing stable or decreasing rates from 2010 to 203555. Globally, the European region is traditionally characterized by a high incidence and prevalence of TC. However, with an aging population and a declining proportion of individuals aged 15–39 years, this trend may influence future incidence rates56. In contrast, Africa, where TC incidence remains comparatively low, is expected to experience substantial growth in the population aged 15–39 years due to persistently high fertility rates56. This demographic shift could contribute to global trends and potential shifts in the burden of TC across regions and years. Further evidence is essential to validate these observations.

Limitations.

The GBD database provides a robust platform for global health research, yet there are several inherent limitations in our secondary analysis. The primary limitation is the absence of detailed data on testicular cancer subtypes. By aggregating all testicular cancer into a single category, the database obscures the distinct epidemiological and clinical profiles of subtypes such as germ cell tumor and sex cord-stromal tumor. This lack of specificity hampers our ability to analyze the burden and trends associated with each subtype. Additionally, the variability in data quality across 204 countries and territories, particularly in low-income areas with underdeveloped healthcare systems. The lack of robust cancer registries and limited access to diagnostic tools can result in underreporting or misclassification of testicular cancer cases, thereby affecting the accuracy of global estimates. Finally, the efficacy of BAPC model is heavily reliant on the quality of GBD data. Errors or biases within GBD data can directly undermine the reliability of BAPC prediction results. Despite the fact that the BAPC model is effective in capturing trends in existing data, the predictive power of the model may be reduced when making long-term forecasts due to uncertain external factors, such as health policy changes and environmental incidents (e.g., epidemics, war, nuclear leakage). However, the BAPC model does not permit the incorporation of other influencing factors in its analysis process. Therefore, further research is needed to improve the BAPC model and to accumulate more evidence to support its accuracy. Despite these challenges, the GBD database remains a vital resource for public health. Its comprehensive scope and ability to provide standardized estimates across diverse regions and populations offer valuable insights that are crucial for guiding global health initiatives.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this study clearly indicated that the burden of TC among AYAs worldwide has increased continuously from 1990 to 2021, with varying impacts from population growth, epidemiological changes, and aging demographics. Furthermore, significant disparities existed across age groups, geographic regions, and SDI levels. These insights point to the critical need for heightened awareness of TC risk factors among AYAs and the implementation of comprehensive primary and secondary prevention strategies. Additionally, reinforcing healthcare infrastructure, especially in regions with lower and low - middle SDI, and ensuring the application of effective treatment strategies are essential for alleviating the burden of testicular cancer among adolescents and young adults.

Data availability

The data is obtained from a publicly available database, viewable through this link: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

References

Patrikidou, A. et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Testicular Cancer: 2023 update. Eur. Urol. 84, 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.04.010 (2023).

Miller, K. D. et al. Cancer statistics for adolescents and young adults, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70, 443–459. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21637 (2020).

McHugh, D. J., Gleeson, J. P. & Feldman, D. R. Testicular cancer in 2023: current status and recent progress. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 167–186. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21819 (2024).

Rajpert-De Meyts, E., McGlynn, K. A., Okamoto, K., Jewett, M. A. S. & Bokemeyer, C. Testicular germ cell tumours. Lancet 387, 1762–1774. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00991-5 (2016).

Cheng, L. et al. Testicular cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4, 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0029-0

Zhou, X. et al. Trends in the global, regional, and national burden of testicular canc er from 1990 to 2019: an observational study with 30-year global data. Int. J. Surg. 110, 4633–4647. https://doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000001603 (2024).

Pishgar, F. et al. Global, regional and national burden of testicular cancer, 1990–2016: results from the global burden of Disease Study 2016. BJU Int. 124, 386–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14771 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. Time trends in the mortality of testicular cancer across the BRICS: an age-period-cohort analysis for the GBD 2019. Sci. Rep. 14, 12740. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63191-9 (2024).

Tverye, A., Nangia, A. & Fantus, R. J. Testicular cancer survivorship and fertility preservation. Urol. Clin. North. Am. 51, 429–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2024.03.011 (2024).

van Basten, J. P. et al. Sexual dysfunction in nonseminoma testicular cancer patients is relate d to chemotherapy-induced angiopathy. J. Clin. Oncol. 15, 2442–2448. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2442 (1997).

Wiechno, P., Demkow, T., Kubiak, K., Sadowska, M. & Kamińska, J. The quality of life and hormonal disturbances in testicular cancer sur vivors in Cisplatin era. Eur. Urol. 52, 1448–1454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2007.05.012 (2007).

Chovanec, M. et al. Late adverse effects and quality of life in survivors of testicular ge rm cell tumour. Nat. Rev. Urol. 18, 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-021-00440-w (2021).

McGrady, M. E., Willard, V. W., Williams, A. M. & Brinkman, T. M. Psychological outcomes in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 707–716. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.01465 (2024).

GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 2100–2132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00367-2 (2024).

GBDRF Collaborators. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 coun tries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 2162–2203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00933-4 (2024).

Diseases, G. B. D. (ed Injuries, C.) Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disa bility-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 81 1 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Glob Al Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403 2133–2161 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 (2024).

GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disa bility-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 81 1 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Glob Al Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 2133–2161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 (2024).

Murray, C. J. L. et al. GBD: design, definitions, and metrics. Lancet 380, 2063–2066. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61899-6 (2012).

Stevens, G. A. et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet 388, e19–e23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9 (2016).

GBD Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1160–1203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30977-6 (2020).

Global Burden of Disease Study Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) 1950–2021., (2024). https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/global-burden-disease-study-2021-gbd-2021-socio-demographic-index-sdi-1950%E2%80%932021

Fay, M. P. & Feuer, E. J. Confidence intervals for directly standardized rates: a method based o n the gamma distribution. Stat. Med. 16, 791–801 (1997).

Anderson, R. N. & Rosenberg, H. M. Age standardization of death rates: implementation of the year 2000 Standard. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 47, 1–16 (1998).

GBD Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific mortality, life expectancy, and population est imates in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1950–2021, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive d emographic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 1989–2056. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00476-8 (2024).

Joinpoint Regression Program. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/

Kim, H. J., Fay, M. P., Feuer, E. J. & Midthune, D. N. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat. Med. 19, 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z (2000).

Tuo, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Thalassemia, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. EClinicalMedicine 72, 102619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102619 (2024).

Das Gupta, P. Standardization and decomposition of rates from cross-classified data. Genus 50, 171–196 (1994).

Das Gupta, P. A general method of decomposing a difference between two rates into se veral components. Demography 15, 99–112 (1978).

Hu, J. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of CKD due to glomerulonephritis from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 60–71. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.0000000000000017 (2023).

Xie, Y. et al. Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study highlights the global, regional, and national trends of chronic kidney disease epidemiology f rom 1990 to 2016. Kidney Int. 94, 567–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.04.011 (2018).

Riebler, A. & Held, L. Projecting the future burden of cancer: bayesian age-period-cohort ana lysis with integrated nested Laplace approximations. Biom. J. 59, 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1002/bimj.201500263 (2017).

Chen, J. et al. Global burden of non-communicable diseases attributable to kidney dysfunction with projection into 2040. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). https://doi.org/10.1097/CM1099.0000000000003143 (2024).

Du, Z., Chen, W., Xia, Q., Shi, O. & Chen, Q. Trends and projections of kidney cancer incidence at the global and na tional levels, 1990–2030: a bayesian age-period-cohort modeling study. Biomark. Res. 8, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-020-00195-3 (2020).

Fertility, G. B. D. & Forecasting, C. Global fertility in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2021, with for ecasts to 2100: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 2057–2099. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00550-6 (2024).

IHME. Global Fertility, Mortality, Migration, and Population Forecasts 2017–2100. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-population-forecasts-2017-2100 (2024).

Safiri, S. et al. The burden of testicular cancer from 1990 to 2019 in the Middle East and North Africa region. Front. Oncol. 13, 1276965. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1276965 (2023).

Leão, R. et al. irculating microRNAs, the next-generation serum biomarkers in testicular germ cell tumours: a systematic review. Eur. Urol. 80, 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2021.06.006 (2021).

McGlynn, K. A. & Trabert, B. Adolescent and adult risk factors for testicular cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 9, 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2012.61 (2012).

International Germ Cell. Consensus classification: a prognostic factor- based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 15, 594–603. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.594 (1997).

Chovanec, M. & Cheng, L. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of testicular cancer. BMJ 379, e070499. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-070499 (2022).

Znaor, A., Lortet-Tieulent, J., Laversanne, M., Jemal, A. & Bray, F. International testicular cancer incidence trends: generational transitions in 38 countries 1900–1990. Cancer Causes Control 26, 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0486-z (2015).

Cheng, L. et al. Testicular cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4, 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0029-0 (2018).

Mucci, L. A. et al. Familial risk and heritability of cancer among twins in nordic countries. JAMA 315, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.17703 (2016).

Litchfield, K. et al. Quantifying the heritability of testicular germ cell tumour using both population-based and genomic approaches. Sci. Rep. 5, 13889. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13889 (2015).

Chertack, N. et al. Overcoming sociodemographic factors in the care of patients with testi cular cancer at a safety net hospital. Cancer 126, 4362–4370. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33076 (2020).

Znaor, A. & Bray, F. Thirty year trends in testicular cancer mortality in Europe: gaps persist between the East and West. Acta Oncol. 51, 956–958. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.681701 (2012).

Aareleid, T., Sant, M. & Hédelin, G. Improved survival for patients with testicular cancer in Europe since 1978. EUROCARE Working Group. Eur. J. Cancer. 34, 2236–2240. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00313-x (1998).

Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission. The Report on Drug Use in the Americas 2019. Report No. 978-0-8270–6793-6 (Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission, Organization of American States, 2019).

Castillo-Carniglia, A. et al. Trends in marijuana use in two latin American countries: an age, period and cohort study. Addiction 115, 2089–2097. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15058 (2020).

Daling, J. R. et al. Association of marijuana use and the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer 115, 1215–1223. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24159 (2009).

Barrios, C. H. et al. Cancer control in Latin America and the Caribbean: recent advances and opportunities to move forward. Lancet Oncol. 22, e474–e487. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00492-7 (2021).

de Souza, J. A., Hunt, B., Asirwa, F. C., Adebamowo, C. & Lopes, G. Global health equity: cancer care outcome disparities in high-, middle -, and low-income countries. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.2860 (2016).

Le Cornet, C. et al. Testicular cancer incidence to rise by 25% by 2025 in Europe? Model-based predictions in 40 countries using population-based registry data. Eur. J. Cancer. 50, 831–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.11.035 (2014).

Znaor, A. et al. Testicular cancer incidence predictions in Europe 2010–2035: a rising burden despite population ageing. Int. J. Cancer. 147, 820–828. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32810 (2020).

Secretariat, P. D. o. t. D. o. E. a. S. A. o. t. U. N. World Population Prospects 2024. https://population.un.org/wpp/ (2024).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation for providing access to the crucial GBD data.

Funding

This study was conducted without financial support from any external agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y, Z.G, and F.X designed the study. S.Y, Z.Q, L.W, and X.C collected the data and performed the analyses. S.Y, Z.G, Z.Q, L.W, X.C and F.X wrote the manuscript. FX supervised the project. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript and take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, S., Guo, Z., Qiu, Z. et al. Global burden and trends of testicular cancer in adolescents and young adults from 1990 to 2021, with predictions to 2035. Sci Rep 14, 31787 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82897-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82897-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Disease burden of bladder cancer in China and the different SDI regions over the world from 1990 to 2021

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Global, regional, and national epidemiology of ischemic stroke in young adults, 1990–2021

Journal of Neurology (2025)