Abstract

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), which is caused by mutations in the NOTCH3 gene, is associated with early-onset strokes. However, the specific genetic and imaging characteristics associated with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) in patients with CADASIL remain unclear. We reviewed CADASIL patients with NOTCH3 mutations, dividing them into two groups based on the presence of clinically relevant AIS lesions on diffusion-weighted imaging, observed at any time, regardless of the timing of CADASIL diagnosis. Clinical, imaging, and genetic features were compared between these groups. Genetic variations were categorized by exon location: specifically, exon 3 including Arg75Pro, and exon 11 including Arg544Cys, were examined in detail. Factors associated with AIS in CADASIL patients were analyzed. A total of 141 patients were included, of whom 70 (49.6%) were diagnosed with AIS. While there were no significant differences in vascular risk factors between the two groups, patients with AIS had a higher prevalence and greater number of lacunes (p < 0.001) and exhibited more severe white matter changes (p = 0.007). CADASIL patients with AIS had a higher rate of exon 3 variant and a lower rate of exon 11 variant compared to those without AIS. Multivariable analysis revealed that exon 11 variants were associated with a reduced risk (aOR = 0.270, 95% CI 0.099–0.733; p = 0.010). CADASIL who experienced AIS had unique genetic and imaging characteristics when compared to those who did not experience AIS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is one of the most common hereditary cerebral small vessel diseases, caused by mutations in the NOTCH3gene1Clinically, CADASIL is characterized by a wide array of symptoms, including headaches, depression, dementia, and recurrent cerebrovascular events such as intracerebral hemorrhage and acute ischemic strokes (AIS), which often present early in life2The neurological impairments resulting from AIS in CADASIL patients can significantly affect their quality of life. However, the exact mechanisms underlying AIS in CADASIL remain incompletely understood3.

While traditional vascular risk factors have been implicated in the occurrence of AIS among patients with CADASIL4,5, genetic mutations in the NOTCH3gene that regulate cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis may also play an essential role. This signaling pathway is crucial for sustaining vascular integrity and function, especially in the central nervous system6 Specifically, the NOTCH3gene consists of 33 exons, with the majority of pathogenic mutations associated with CADASIL located in exons 2 to 24, which encode the 34 epidermal growth factor-like repeat (EGFR) domains7 Microscopically, these mutations result in the abnormal accumulation of the NOTCH3extracellular domain around vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes, contributing to endothelial dysfunction and subsequent ischemia8,9 Specific variants within the EGFR domains of NOTCH3have been significantly correlated with the severity of small vessel disease and the onset of stroke10.

Despite these insights, previous studies comparing the influence of different exons on the incidence of AIS in CADASIL are limited2 Furthermore, there is a notable lack of research exploring the connections between the occurrence of AIS and the genotypic and imaging characteristics of CADASIL patients. This study aims to address this gap by investigating the relationships among the clinical, imaging, and genetic features of CADASIL patients with and without AIS.

Results

The study included a total of 141 patients. The mean age at the time of initial imaging assessment was 51 ± 12 years. Among the participants, 62 (44.0%) were male, and 31 (22.0%) had a family history of CADASIL. Of the study patients, 70 (49.6%) had experienced at least one AIS as confirmed by DWI. A total of 41 distinct NOTCH3 variants were identified, spanning exons 2 to 24 of the NOTCH3 gene (Supplementary Table 1). The majority of these variants were concentrated in exon 3 (n = 37, 26.2%) and exon 4 (n = 25, 17.7%). A high frequency of variants was also observed in exon 11 (n = 39, 27.6%; Fig. 1A). Notably, most of the variants were clustered in the proximal region of NOTCH3, specifically within the regions encoding EGFRs 1–6. (Fig. 1B)

Comparison of CADASIL patients according to whether they experienced AIS

A comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with AIS and those without is presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in vascular risk factors between the two groups. Regarding the genetic test results, there was no significant difference in the EGFR 1–6 domain between the groups (60.6% vs. 50.7%; p = 0.252). However, patients with AIS had a higher rate of exon 3 variant (36.4% vs. 19.4%) and a lower rate of exon 11 variant (19.7% vs. 38.8%) compared to those without (p = 0.022).

Both the prevalence of lacunes (91.3% vs. 57.7%; p < 0.001) and the average number of lacunes (5.2 ± 4.8 vs. 2.9 ± 4.1; p = 0.003) were significantly higher in those with AIS. The presence and quantity of CMBs did not differ significantly between the two groups. Similarly, the severity of PVS showed no significant difference. Notably, deep WMH was more severe in those with AIS compared to those without (p = 0.007), whereas periventricular WMH did not show significant differences between the two groups. The characteristic findings of CADASIL, including involvement of the anterior temporal pole and external capsule, were also comparable between the two groups (Table 2). The most frequently affected location in AIS were corona radiata (40.0%), subcortex (37.1%), and centrum semiovale (22.9%). Furthermore, AIS lesions were sequentially observed in the splenium, internal capsule, basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellum (Table 3).

Factors associated with AIS in CADASIL

In univariable analysis, the presence of lacunes, deep WMH, the exon 3 variant, and the exon 11 variant were associated with AIS. (Table 4). A multivariable analysis was conducted by adjusting for age, sex, vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, smoking history), and the presence of lacunes and deep WMH. The location of the mutation was dichotomized in each model.

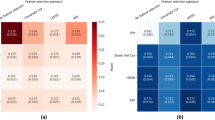

In model 1, which focused on exon 3, the exon 3 variant (reference: all other variants except exon 3) did not show a statistically significant association with the risk of AIS (OR = 2.137, 95% CI 0.877–5.207; p = 0.095). In model 2, which focused on the mutation location at exon 11, the exon 11 variant was associated with a lower risk of AIS (reference: all other variants except exon 11; OR = 0.237, 95% CI 0.094–0.597; p = 0.002). In model 3, patients were categorized into three groups: exon 3, exon 11 variant, and others; the exon 11 variant continued to be associated with a lower risk of AIS (reference: others, OR = 0.270, 95% CI 0.099–0.733; p = 0.010; Table 4).

Characteristics of patients with mutation in exon 11

The age of patients with AIS was greater in those with mutations in exon 11 compared to those with mutations in other loci (54.9 ± 13.1 years vs. 49.1 ± 11.1 years; p = 0.011). CADASIL patients with the exon 11 variant showed a higher prevalence of hypertension (35.9% vs. 12.9%; p = 0.002), diabetes (23.1% vs. 6.4%; p = 0.006), and coronary heart disease (10.3% vs. 1.1%; p = 0.026). However, the incidence of AIS was higher in patients with mutations at other loci compared to those with the exon 11 variant (33.3% vs. 56.4%; p = 0.016). There were no significant differences in imaging characteristics between patients with the exon 11 variant and those with mutations at other foci (Table 5).

Kaplan–Meier curves (Fig. 2) showed a significant association between the exon 11 variant and the age of onset for the first stroke. Patients with the exon 11 variant had a significantly older age at the initial stroke occurrence compared to those with mutations at other loci, as indicated by the log-rank test (p = 0.001). This finding translated into a protective effect (OR = 0.308; 95% CI, 0.165–0.575) against the risk of stroke in patients with exon 11 variants (p < 0.001).

Kaplan-Meier analysis of stroke-free survival in CADASIL patients based on exon variants. This figure shows the probability of remaining stroke-free over time, stratified by genotype. The blue line represents patients with an Exon 11 NOTCH3 variant, while the green line represents patients with other variants.

Discussion

This study delineates the distinctive features of CADASIL patients with AIS. The average age of onset for AIS in CADASIL patients was 55 years, which is relatively younger compared to typical patients with lacunar strokes11 Interestingly, there were no discernible differences in conventional stroke risk factors between CADASIL patients with AIS and those without. However, CADASIL patients with AIS exhibited a higher frequency of old lacunes and more extensive subcortical WMH compared to those without AIS.

In terms of genetic variation, there was a higher occurrence of exon 3 variants and a lower incidence of exon 11 variants among CADASIL patients with AIS. Previous studies have demonstrated that mutations in EGFR domains 1–6 are associated with earlier stroke onset, lower survival rates, and more severe WMH, likely due to increased extracellular NOTCH3aggregations and deposits of granular osmophilic material12,13However, in our cohort, no significant difference in the occurrence of AIS was observed with EGFR mutations in domains 1–6. The previous studies were primarily conducted in Western populations, where the genotype of CADASIL patients differs from that of Asian populations14,15For instance, specific mutations, such as the Arg544 Cys mutation in exon 11 and the Arg75Pro mutation in exon 3, were found to be more prevalent among East Asian CADASIL patients14.

Interestingly, despite the exon 11 variant group having more conventional stroke risk factors (e.g., age, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease), they exhibited a lower incidence of AIS and a delayed onset of the first stroke by approximately six years compared to mutations in other loci. This observation suggests that genetic factors may play a more significant role in stroke risk among CADASIL patients. Notably, the Arg544 Cys mutation was identified in 23 out of 39 patients (62.1%) with exon 11 mutations, with 7 of these 23 patients (30.4%) experiencing AIS (Supplementary Table 2). Mutations occurring outside the EGFR domains 1–6 may lead to a milder disease presentation10 It is hypothesized that the Arg544 Cys mutation, located between EGFR domains in exon 11, results in less aggregation of the extracellular domain compared to typical CADASIL mutations, potentially delaying symptom onset and reducing the incidence of AIS.

On the other hand, variants in exon 3 were associated with a higher incidence of AIS, affecting 68.0% of patients, including those with the Arg75Pro mutation (Supplementary Table 2). Although patients with CADASIL who have the Arg75Pro mutation exhibit atypical and milder phenotypes—characterized by a lower frequency of stroke or transient ischemic attacks and fewer temporal pole lesions16—this mutation has also been linked to an increased risk of CMBs and intracerebral hemorrhages, thereby heightening the risk of bleeding17Generally, the presence of CMBs elevates the risk of both ischemic small vessel disease and intracerebral hemorrhage18 The Arg75Pro mutation may contribute to increased aggregation and solubility of the NOTCH3extracellular domain, leading to small vessel toxicity and damage19,20 However, the statistical significance between exon 3 and AIS was lost after adjustment for imaging findings (Supplementary Tables 3 and Table 4). Exon 3 mutations show unique imaging characteristics. Further study focusing on the association between Exon 3 mutations, imaging characteristics such as multiple CMBs or more lacunes, and increased risk of ischemic events may be warranted.

The limitations of this study include its single-center, retrospective design. However, our center receives numerous referrals for rare diseases from across the nation. Additionally, whole-genome sequencing was not performed for genotypic analysis. Lastly, we analyzed genetic characteristics based on the location of mutations within exons. Although trends were observed for individual gene loci (Supplementary Table 2), statistical significance was constrained due to the smaller sample size. Larger multi-center or multinational cohort studies are necessary to validate our findings.

In conclusion, our study confirmed that the incidence of AIS in patients with CADASIL varies based on the location of mutations in the NOTCH3 gene, regarding the influence of different exons. Specifically, variants in exon 11 were linked to a lower risk of AIS.

Methods

Patients and samples

We conducted a retrospective review of data pertaining to CADASIL patients at Asan Medical Center from January 2002 to December 2022. The diagnosis of CADASIL was confirmed through genetic testing for individuals exhibiting CADASIL symptoms, typical MRI findings, or a family history of CADASIL, as determined by neurologists. We excluded patients who (1) were unable to provide both genetic and imaging data, and (2) had a suspected history of stroke. AIS was defined as acute neurological deficit with a clinically relevant DWI lesion, regardless of the timing of the CADASIL diagnosis. The radiological definition of AIS is described below.

Demographic and clinical data were extracted from medical records. The presence of vascular risk factors, patients’ initial chief symptom and initial functional status was assessed at the time of initial acute stroke onset in CADASIL patients with AIS and during the first MRI in CADASIL patients without AIS. Initial clinical symptoms was categorized as unilateral hemiparesis, dysartrhia, gait disturbance, dizziness, cognitive impairment, headache and others. Initial functional status was measured by modified Ranken Scale by the attending neurologists.

All patients suspected of having CADASIL had 5 mL of fasting venous blood extracted into tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as an anticoagulant (BD Vacutainer K2EDTA spray-coated tubes). Immediately after collection, the blood samples were placed in an icebox to maintain a stable temperature and transported to the laboratory within one hour for processing. In the laboratory, samples were processed within 2 h of collection to isolate plasma or extract DNA as required for genetic analysis. Any samples not processed within this timeframe were discarded to maintain the integrity of the specimens. All handling and processing of blood samples were conducted in accordance with biosafety regulations to ensure the safety of laboratory personnel and the quality of the sample.

This study received approval from the local ethics committee (IRB number: 2023 − 0381), and patient informed consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Imaging and diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke

MRI examinations were conducted using either a 1.5-T Siemens Avanto (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA, USA) or a 3.0-T Philips scanner (Philips Healthcare, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). The imaging protocol included axial DWI, T2-weighted imaging, fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR), gradient-echo (GRE), and/or susceptibility-weighted image (SWI) sequences.

An AIS lesion was defined as a hyperintense area on DWI with a corresponding reduced signal on the apparent diffusion coefficient image, with or without an increased signal on FLAIR or T2-weighted imaging. These findings corresponded with typical vascular territories, and the location of recent infarction was categorized into distinct cerebral regions, including the subcortex (i.e., juxta-subcortex, centrum semiovale), corona radiata, basal ganglia, internal capsule, thalamus, splenium, brainstem, and cerebellum. Multiple lesion locations were defined if a patient had separated ischemic lesions, with each location classified as a separate location variable. Consequently, a single patient could have multiple values for the locations of stroke lesions.

Small vessel disease burden

Lacunes were defined as rounded or ovoid lesions measuring 3 to 20 mm in diameter, located in the basal ganglia, internal capsule, centrum semiovale, or brainstem. These lesions exhibited cerebrospinal fluid signal intensity on T2-weighted and FLAIR images, typically presenting with a hyperintense rim on FLAIR and no increased signal on DWI. Microbleeds were identified as small (< 5 mm), homogeneous, round foci of low signal intensity on GRE and/or SWI in the cerebellum, brainstem, basal ganglia, white matter, or cortico-subcortical junction. They were distinguished from vessel flow voids and mineral deposits in the globus pallidus. Deep and periventricular white matter hyperintensities (WMH) were both classified according to the Fazekas scale, which ranges from 0 to 3. Perivascular spaces (PVS) were defined as small (< 3 mm) punctate (if perpendicular) or linear (if longitudinal to the plane of the scan) hyperintensities on T2-weighted images in the basal ganglia or centrum semiovale. PVS were rated using a previously described and validated semiquantitative scale ranging from 0 to 421 To ascertain markers of small vessel disease, two experienced researchers (JY Park and SH Ha), who were blinded to the patients’ clinical information, independently interpreted the images and reached consensus decisions.

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA samples were isolated from peripheral blood using PUREGENE DNA isolation kits (Gentra, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The exons of the NOTCH3 gene and their flanking intronic sequences were amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using 11 primer sets. The size and purity of the PCR products were confirmed by separation on 1.2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. DNA sequencing was subsequently performed using the same primers employed for PCR, following the manufacturer’s protocol for the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Electrophoresis and analysis were conducted using an ABI 3130XL genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

To evaluate the pathogenicity of novel missense variants, several bioinformatics tools were employed, including PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2), MutationTaster (http://mutationtaster.org), and Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT) (http://sift.jcvi.org). The frequencies of each variant were assessed using the gnomAD database (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org).

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of CADASIL patients with and without AIS were compared. Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations (SDs), while categorical variables are presented as percentages. Statistical analyses included t-tests and Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables, and Pearson’s χ² test, Fisher’s exact test, or linear-by-linear association tests for categorical variables.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were employed to identify factors, including genetic variants, associated with AIS in patients with CADASIL. The multivariate model incorporated demographic information and vascular risk factors, such as age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, smoking history, and genetic variants. The odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported.

To evaluate the time to onset of the first ischemic stroke across various genotype groups, Kaplan-Meier analyses were conducted with age as the time scale. Cox proportional hazard regression models were employed to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) for AIS in these groups, adjusting for the same factors used in the logistic regression model. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), and a p-value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Chabriat, H., Joutel, A., Dichgans, M., Tournier-Lasserve, E. & Bousser, M. G. Cadasil Lancet Neurol. 8, 643–653 (2009).

Yamamoto, Y., Liao, Y. C., Lee, Y. C., Ihara, M. & Choi, J. C. Update on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and biomarkers of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. J. Clin. Neurol. 19, 12–27 (2023).

Chabriat, H. et al. Clinical spectrum of CADASIL: a study of 7 families. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Lancet 346, 934–939 (1995).

Lin, H. J. et al. Modifiable vascular risk factors contribute to stroke in 1080 NOTCH3 R544C carriers in Taiwan biobank. Int. J. Stroke (2024). 19,105 – 13.

Sukhonpanich, N., Koohi, F., Jolly, A. A. & Markus, H. S. Changes in the prognosis of CADASIL over time: a 23-year study in 555 individuals. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry (2024).

Zaucker, A., Mercurio, S., Sternheim, N., Talbot, W. S. & Marlow, F. L. notch3 is essential for oligodendrocyte development and vascular integrity in zebrafish. Dis. Model. Mech. 6, 1246–1259 (2013).

Opherk, C., Peters, N., Herzog, J., Luedtke, R. & Dichgans, M. Long-term prognosis and causes of death in CADASIL: a retrospective study in 411 patients. Brain 127, 2533–2539 (2004).

Stenborg, A., Kalimo, H., Viitanen, M., Terent, A. & Lind, L. Impaired endothelial function of forearm resistance arteries in CADASIL patients. Stroke 38, 2692–2697 (2007).

Locatelli, M., Padovani, A. & Pezzini, A. Pathophysiological mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Front. Pharmacol. 11, 321 (2020).

Hack, R. J. et al. Three-tiered EGFr domain risk stratification for individualized NOTCH3-small vessel disease prediction. Brain 146, 2913–2927 (2023).

Arboix, A., Garcia-Eroles, L., Massons, J., Oliveres, M. & Targa, C. Lacunar infarcts in patients aged 85 years and older. Acta Neurol. Scand. 101, 25–29 (2000).

Cho, B. P. H. et al. Association of NOTCH3 variant position with stroke onset and other clinical features among patients with CADASIL. Neurology 99, e430–e439 (2022).

Rutten, J. W. et al. The effect of NOTCH3 pathogenic variant position on CADASIL disease severity: NOTCH3 EGFr 1–6 pathogenic variant are associated with a more severe phenotype and lower survival compared with EGFr 7–34 pathogenic variant. Genet. Med. 21, 676–682 (2019).

Kim, Y. et al. Genotype and phenotype differences in CADASIL from an Asian perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022).

Tang, S. C. et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of stroke patients with p.R544C NOTCH3 mutation in Taiwan. Ann. Clin. Transl Neurol. 6, 121–128 (2019).

Mizuno, T., Mizuta, I., Watanabe-Hosomi, A., Mukai, M. & Koizumi, T. Clinical and genetic aspects of CADASIL. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 91 (2020).

Takei, J. et al. Microbleed clustering in thalamus sign in CADASIL patients with NOTCH3 R75P mutation. Front. Neurol. 14, 1241678 (2023).

Puy, L. et al. Cerebral microbleeds and the risk of incident ischemic stroke in CADASIL (Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy). Stroke 48, 2699–2703 (2017).

Mizuta, I., Nakao-Azuma, Y., Yoshida, H., Yamaguchi, M. & Mizuno, T. Progress to clarify how NOTCH3 mutations lead to CADASIL, a hereditary cerebral small vessel disease. Biomolecules 14 (2024).

Ishiyama, H. et al. Pro-Hemorrhagic cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy associated with NOTCH3 p.R75P mutation with low vascular NOTCH3 aggregation property. Ann. Neurol. 95, 1040–1054 (2024).

Appleton, J. P. et al. Imaging markers of small vessel disease and brain frailty, and outcomes in acute stroke. Neurology 94, e439–e452 (2020).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research was supported by the Brain Convergence Research Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020M3E5D2 A01084576) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1 A2 C2100077).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. JY Park contributed to the study concept, study design, data collection, data interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. Dr. JY Song, Dr. JY Chang, Dr. DW Kang, Dr. SU Kwon, Dr. JH Suh, Dr. HJ Kim, Dr. JS Lim, Dr. Satoshi Saito contributed to the data interpretation and revising the manuscript. Dr. SH Ha and Dr. BJ Kim contributed to the study concept, study design, data interpretation, and drafting and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by from the Institutional Review Board of Asan medical center, approval number (2023 − 0381).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J.Y., Song, J.Y., Chang, J.Y. et al. Genetic and imaging features of CADASIL patients with acute ischemic stroke. Sci Rep 15, 17113 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00220-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00220-1