Abstract

Eelgrass ecosystems provide essential habitats for species, such as the Hokkai shrimp (Pandalus latirostris), supporting biodiversity and fisheries. Understanding shrimp behavior in these environments is vital for conservation efforts, yet accurately tracking shrimp movement in controlled tank settings is challenging because of surface reflections and parallax distortions. This study primarily focuses on developing and evaluating a You Only Look Once (YOLO) tracking system for Hokkai shrimp in aquaria. We implemented preliminary measures to address reflection artifacts and parallax distortions; however, our core contribution is the robust detection performance of YOLOv8. Through controlled tank experiments, the system demonstrated high detection accuracy and captured metrics such as distance, velocity, and angle. The results showed a high detection accuracy, with success rates of 95.65% and 100% from the front and side views, respectively, ensuring reliable data on shrimp movement in aquaria. These outcomes provide a robust foundation for high-precision measurements in future ecological or aquaculture studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ecosystem services1,2,3 are defined as the benefits humans derive from ecosystems and fall into four categories: provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural services (MEA Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA)4). The economic value of these ecosystem services is frequently expressed in monetary units, and their valuation is crucial to alert policymakers to the significance of natural ecosystems. Seagrass and algae ecosystem services are recognized as being especially valuable5,6,7. Eelgrass ecosystems provide a range of valuable ecosystem services in coastal areas and serve as vital aquatic habitats8. Eelgrass plays a role in carbon sequestration and biodiversity and provides an optimal environment for the reproduction and habitation of aquatic organisms9,10. Eelgrass serves as the foundation for the food chain and plays a significant role in fisheries. Nevertheless, it remains challenging to accurately quantify these ecosystem services. The effective collection and analysis of detailed data on organism behavior and habitat use is hindered by the lack of suitable methods. Furthermore, traditional approaches have not provided sufficient spatial and temporal resolutions.

The Hokkai shrimp (Pandalus latirostris) is a marine crustacean that inhabits coastal waters along northern Japan and Primorye in Russia. It is a marine species, capable of tolerating a wide range of salinities, and is found in seaweed ecosystems such as eelgrass11,12. It is crucial to understand the influence of Hokkai shrimp behavior and habitat utilization on ecosystem services, as this knowledge is vital for the advancement of environmental conservation and the implementation of sustainable fisheries management strategies.

Despite their ecological and economic importance, precise observation of Hokkai shrimp behavior in controlled settings faces two major challenges—reflections on the aquarium glass surface and distance measurement errors due to depth parallax (see Figs. 1 and 2). In this study, we primarily focus on the novel application of the YOLOv8 model to track Hokkai shrimp by leveraging a custom training dataset that captures the unique conditions of aquarium environments. While the use of reflection and parallax modification techniques represents an exploratory effort to further enhance detection accuracy, our main contribution is demonstrating how a machine learning approach can be effectively tailored to monitor the movement of Hokkai shrimp. This refined tracking method enables more accurate measurement of shrimp trajectories, which is critical for understanding their habitat use within eelgrass beds—ecosystems that are not only vital for biodiversity but also hold significant economic value, with shrimp often traded at premium prices exceeding 10,000 yen per kilogram. Given the small size and cryptic behavior of Hokkai shrimp, improved observation methods are essential to advance our knowledge of their migratory ecology and support future conservation and sustainable fisheries management initiatives.

Accordingly, our objectives were twofold.

-

1.

To demonstrate the applicability and effectiveness of the YOLOv8-based tracking system for Hokkai shrimp (Pandalus latirostris) using our custom training dataset.

(The emphasis is on adapting YOLOv8 to the unique challenges of tracking a single shrimp in controlled aquarium settings, thereby highlighting the advantages of a machine learning approach in ecological studies.)

-

2.

To explore auxiliary techniques for improving detection accuracy under challenging imaging conditions, including reflections from the tank surface and depth-induced parallax effects.

(We implement a simple proximity-based filtering for reflection removal and a horizontal barrel distortion correction for mitigating parallax errors. Detailed quantitative assessments of these techniques are deferred to future work.)

By integrating these approaches with the YOLOv8 tracking system, it is feasible to precisely ascertain the distance, velocity, and angle of movement of Hokkai shrimp within aquaria. This not only demonstrates the potential of machine learning techniques in ecological applications but also lays the foundation for sustainable fisheries management and biodiversity conservation by enabling accurate behavioral analyses in controlled environments.

Related works

Tracking system for organisms in the aquarium

Tracking of organisms in aquariums is a particularly prevalent practice in aquaculture. Despite the existence of several proposed methodologies, it has been observed that invasive tracking can have a significant impact on the behavior of organisms within an aquarium environment13. In particular, acoustic telemetry14,15,16 technology, which captures and tracks ultrasonic signals emitted from tags, is susceptible to noise and expensive17. Considering these considerations, technologies based on machine vision, sensors, and utilization of acoustic information represent a significant alternative avenue for exploration18. Although two-dimensional (2D)19,20,21,22 and three-dimensional (3D)23,24,25 machine vision tracking methods have been proposed, 3D is preferable for ecological surveys because it is not possible to observe the movement of living organisms in three dimensions in 2D26,27.

For example, Al Muskit et al.28 demonstrated the application of a YOLOv3-based model (YOLO-Fish) for automated fish detection in underwater environments, effectively addressing challenges such as low illumination and complex backgrounds. Similarly, Xiao et al.29 recently employed a YOLOv8-based multi-object tracking framework (Yolo-AWD + CBT) for precise and real-time tracking of fish in aquaculture, overcoming issues related to occlusion and variable body shapes.

In the context of 3D ecological surveys, subject tracking is typically conducted using a combination of multiple cameras or depth cameras. For example, zebrafish observations have been conducted using multiple cameras. The coordinate points measured by each camera were then reconstructed in three-dimensional space using Microsoft Excel software30.

Nevertheless, fish tracking system in aquariums is not without its limitations, as demonstrated by Yupeng Mei (2022)17. According to Yupeng (2022), in fish tracking (a) occlusion, (b) morphological changes, (c) scale change, (d) background interference, (e) image blur, (f) changes in illumination, (g) turbid water, and (h) low resolution. In this study, only scale change (c) was problematic because the subject was a single organism in an aquarium under ideal experimental conditions. In addition, the reflection of organisms on the tank surface is an important issue to be resolved. While scale adaptive tracking improves tracking accuracy for changes in the scale of organisms in the tank, it does not adjust the scale itself, so accurate distance measurement is still difficult. Ecologically speaking, observing shrimp activity may help identify patterns of habitat usage in eelgrass meadows. However, this study only looks at one shrimp in a controlled tank; field applications will be investigated later.

False detection of reflected objects and its improvement

It is an inherent characteristic of the photographic process that the object being photographed will reflect off the glass surface when shooting through it31,32. Therefore, techniques have been proposed to remove reflections from captured images. Existing reflection removal methods can be classified into single image reflection removal methods and multiple images reflection removal methods. Single image reflection removal can be further classified into conventional methods that do not use deep learning and those that use deep learning, respectively. Multiple Images Reflection Removal can be classified into two categories: those that capture multiple types of images at once using a single device, and those that record multiple images by changing their positions and poses from a single device33. However, these methods are not general purpose, as the accuracy of reflection rejection is contingent upon the environmental conditions and the characteristics of the object in question. Furthermore, methods that necessitate the use of specialized cameras and devices are subject to financial constraints. Instead of doing a thorough comparison examination of these sophisticated reflection removal techniques, we just use a simple proximity-based filtering to handle reflections in our study. As a result, we are not currently equipped to do a comprehensive quantitative validation of reflection elimination efficacy.

Theoretical issues related to the influence of parallax and depth information

The application of vision sensors for the measurement of objects in liquids is complicated by the phenomenon of image distortion. This phenomenon is caused by the refraction of light at the boundary between air, liquid, and glass, which results in the formation of distorted images and subsequent ranging errors34. A camera system comprising trapezoidal glass and a microlens array was put forth as a potential solution for correcting image distortion. This approach proved effective in correcting distortions around the tank35,36. However, these studies address image distortion caused by medium differences exclusively. To the best of the author’s knowledge, there are few previous studies on scale changes of objects. Our work just uses a preliminary horizontal barrel distortion for the aquarium scenario, whereas many earlier attempts concentrate on intricate optical corrections. More precise parallax correction might be possible with a more thorough geometric calibration or multi-camera technique, but this evaluation is still for future research.

Experimental methods

YOLOv8

YOLOv8, which was introduced by Ultralytics37 in 2023. The model offers five scaled versions, designated as YOLOv8n (nano), YOLOv8s (small), YOLOv8m (medium), YOLOv8l (large), and YOLOv8x (extra large), which are intended to meet the diverse requirements of potential applications. YOLOv8n38 was used in this study. The YOLOv8 model incorporates numerous architectural, and developer experience changes and improvements over YOLOv539. YOLOv8n was selected for its lightweight architecture, high detection accuracy, and real-time processing capabilities, which are particularly advantageous for tracking applications under controlled tank conditions. While other object detection models exist, a detailed comparison was beyond the scope of this study. However, the performance and simplicity of YOLOv8n made it the most appropriate choice for our objectives. Furthermore, although the training data, code, and complete experimental results are currently available upon request, we plan to release these resources on platforms such as GitHub in future revisions to promote replication and further research in this area.

Training the model

By cropping still images from the acquired video data, annotations were made into 209 image datasets, which were subsequently utilized as training data. The data used for training were obtained from two distinct perspectives relative to the aquarium surface. Experts conducted the annotation process using RoboFlow (https://roboflow.com/). Only one classification category, Pandalus latirostris, was utilized. To propose correction techniques for YOLO identification, it is necessary to ensure that the individuals used for the training and testing are identical. The annotation results were transformed into YAML data in compliance with the YOLOv8 format and subsequently exported. Subsequently, the annotated dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and test datasets at a 7:2:1 ratio of respectively.

YOLOv8 (You Only Look Once Version 8) is a framework commonly used for real-time object detection and image segmentation tasks. In this study, the ultralytics library was installed using pip install ultralytics. We selected the YOLOv8n model, a lightweight variant of YOLOv8, and trained it for 100 epochs. An epoch refers to one complete pass through the entire training dataset. During training, the model’s internal parameters—often referred to as weights—are updated to minimize prediction errors on the training data. The weights from the epoch yielding the highest mean Average Precision (mAP) on the validation set were saved and used for subsequent analyses. Figure 3 shows a batch of images used during training, while Fig. 4 presents the training and validation losses for the bounding box regression (box_loss), classification (cls_loss), and distribution focal loss (dfl_loss), along with precision, recall, and mAP at IoU thresholds of 0.5 and 0.5:0.95. The training curves for box_loss, cls_loss, and dfl_loss show a consistent downward trend over 100 epochs. The validation curves display fluctuations around relatively stable values for each loss component. The precision and recall metrics approach high values during the later epochs, and the mAP metrics similarly reach elevated levels, indicating the model’s ability to detect the single class (Pandalus latirostris) in the validation data.

Image processing to reduce reflection on aquarium surface

As the object nears the surface of the tank, it is reflected by different densities of air and water. Reflections result in false detections using YOLO and represent a significant issue. Consequently, if YOLO identifies multiple target objects at time t, the distance between the coordinates of each detection result can be calculated. The detection result that is near the coordinates of the singularly detected object at time t-1 is then considered to be the true target object. This methodology circumvents the issue of false detections resulting from reflections from the tank surface. The Fig. 5 illustrates the process flow during multiple detections by YOLO, providing a visual representation of the process of selecting the closest detected coordinates.

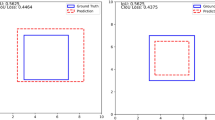

Horizontal barrel distortion conversion

When the image is captured perpendicular to the surface of the tank, the tank surface at the rear appears smaller due to parallax effects, leading to discrepancies in the measured distances between the front and rear sides. To mitigate the distance error caused by parallax, we applied a barrel transformation in the horizontal direction, extending from the image’s center to its periphery, as shown in Fig. 6. It should be noted that the barrel distortion correction employed in this study is a preliminary attempt. Due to resource limitations, we did not perform a full optical calibration using a chequerboard or advanced computer vision libraries such as OpenCV, which are well-documented for such corrections. Instead, we implemented a simple correction based on a zoom factor that varies with the distance from the image center. Specifically, the zoom factor is calculated as follows:

where r is the distance from the pixel coordinates (X, Y) to the image center, and r max is the maximum distance from the image center (e.g., along the diagonal of the image). The corrected horizontal coordinate is computed as:

with the vertical coordinate remaining unchanged. This approach reduces horizontal distortion across the image, thereby lessening the parallax-induced distance errors.

While commercial tools (e.g., GoPro Studio, Adobe Lightroom) or more comprehensive methods using OpenCV could offer higher precision, our choice was motivated by the need for rapid preliminary evaluation, reduced computational cost, and future scalability. In future work, we plan to rigorously compare this simple method with more advanced calibration techniques, including checkerboard-based calibration, to determine the optimal approach for our application.

Experimental settings

The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 7. One Hokkai shrimp (Pandalus latirostris) was placed in a tank measuring 45 cm height, 45 cm width, and 90 cm depth. Subsequently, images were captured using a video camera (GoPro: GoPro HERO10 Black) from the front and side of the tank. The frame rate and quality were set to 60 FPS and 1080P, respectively, and the video was recorded for a total of 12 min and 3 s.

Results and discussion

The proposed tracking technique generates a time-series dataset comprising the coordinates, speed, and angle of the detected object, which is output as a CSV file. The resulting data are shown in Fig. 8. The coordinates represent the midpoint of the boundary box delineated by YOLO, whereas the velocity is quantified as the number of pixels that have undergone a change with respect to the elapsed time. The angles were calculated by determining the change in coordinates with respect to time. At each time point, a single object was identified consistently.

Figures 9, 10, and 11 illustrate the temporal evolution of the angle, velocity, and score, respectively, as a function of time. In particular, the angle is defined as the angle between the coordinates of the previous frame and those of the current frame. It is crucial to consider the influence of experimental conditions and the surrounding environment, particularly during periods of rapid change. The velocity was calculated from the distance of pixel movement between frames, resulting in an average velocity of 164.7 pixels per second. This provides a useful indicator of the speed of the object’s movement, which will be beneficial in future studies. The abrupt acceleration observed at approximately 850 s is postulated to be the result of an erroneous estimation of the tracking parameters. More precise data may be obtained by processing the omitted values in the output CSV file. A frame-by-frame review around the 850-s mark revealed that reflection overlap and partial occlusion momentarily shifted the bounding box, resulting in an artificially high velocity calculation. This suggests that refining reflection filtering thresholds or incorporating additional training data specific to partial occlusions could mitigate such abrupt errors. The score serves as an indicator of the confidence level associated with the objects identified by YOLO, with an average score of 62.7%. It is anticipated that this score will improve with the incorporation of additional training data and the utilization of more diverse datasets, which will be a future challenge.

Figures 12 and 13 illustrate the detection outcomes for each 60-s frame in the video captured from each direction. The results presented herein demonstrate the efficacy of the object detection algorithm, which displays the name, score, speed, and angle in real time for the organism enclosed in the blue bounding box. This display method enhances the practicality of the system by enabling the user to rapidly ascertain the organism’s motion and reliability. In particular, Fig. 12 demonstrates that no detection was performed in the f = 6 frame, but that detection was successfully performed in all other frames. On closer examination, it seems that YOLO missed the target because of the strong reflection on the aquarium glass, which confused the detector at f = 6. Such single-frame identification failures may be avoided in subsequent rounds by modifying the reflection threshold or adding more reflection samples to the training set. This aspect is crucial in evaluating the algorithm’s responsiveness under specific circumstances and should be acknowledged as a potential avenue for future enhancement.

In contrast, Fig. 13 illustrates that the biological detection process was successful in all frames. This is indicative of the system’s stability, particularly in the context of disparate shooting conditions and angles. It serves to reinforce the system’s resilience. Although it is practically challenging to conduct a comprehensive visual verification of all 42,660 frames in each video, the analysis of the 22 extracted frames indicates a detection accuracy of 95.65% for videos captured from the front and 100% for videos captured from the side. This serves to corroborate the high degree of accuracy demonstrated by the experimental results, thereby underscoring the reliability of the algorithm. Nevertheless, a random sampling strategy for frame-by-frame annotation could provide a more comprehensive error analysis than visual inspection of selected frames alone, ensuring that rare detection failures are systematically identified.

Furthermore, Fig. 14 illustrates a three-dimensional graph that plots the coordinates of the output CSV file. The color intensity of yellow indicates the duration of the time lapse, thus providing a visual representation of the trajectory of the moving object. The coordinates demonstrate a pattern that aligns with the observations made by an expert, thereby confirming the efficacy of this tracking system. This provides crucial evidence for the practical implementation of the system and paves the way for future research.

Basic quantitative assessment of logged tracking data

Without further experimental trials, we examined the available log data (more than 40,000 frames) to give a basic quantitative assessment of our YOLO-based tracking outcomes. The Speed and Angle histograms are shown in Fig. 15, and the main descriptive statistics and outlier analyses are compiled in Table 1. According to Table 1, speed had a significant standard deviation of 7606.78 pixels/s and an overall mean of 164.74 pixels/s. It is assumed that the maximum measured speed, which was around 1.37 × 10^6 pixels/s, resulted from brief bounding-box jumps brought on by occlusions or reflections.

We found 66 frames (0.16% of the sample) to be outliers using a 3σ-based threshold of 22,985.09 pixels/s (e.g., Frame No. 3928, Speed = 29,297.84 pixels/s). Such high numbers probably represent situations in which the shrimp’s reflection on the aquarium glass caused incorrectly excessive coordinate shifts. The angle had a standard deviation of 108.53° and an average of -0.62°, ranging from -179.99° to + 180.00°. We calculated the frame-to-frame angle difference and noted any shift greater than 150° in order to identify sudden changes in shrimp heading. Using this criterion, 13,017 frames (or around 32% of the dataset) were found. Although some significant angle shifts might constitute actual abrupt rotations, the majority are probably caused by reflection-induced misalignments in bounding-box identification or partial occlusions. Figure 15 summarizes the data as histograms.

Only a small percentage of frames were classified as “Speed outliers,” as Table 1 illustrates, suggesting that our proximity-based filtering and reflection-removal strategy generally reduced extreme tracking errors. Nonetheless, the comparatively high number of significant angle jumps indicates that more improvement—for example, better filtering settings or more training data for partial occlusions—might be helpful. Despite being early, these evaluations show that speed and angle logs can be useful markers of aquarium-specific aberrations (reflection, parallax) and indicate the possible need for more extensive post-processing or advanced corrective techniques.

Limitation and future work

In this study, visual observation was employed as the evaluation method. However, this approach is inherently subjective and would be enhanced by the incorporation of objective quantitative evaluation metrics. Future work will include a quantitative evaluation using standard metrics, such as Multiple Object Tracking (MOT), to further enhance the precision of the results. Furthermore, although this study concentrated on individual identification, future research will address the identification of multiple subjects.

Additionally, our current tracking system reports velocity in pixels per second, which is less informative for behavioral studies. Given the known dimensions of the tank and the localization data from the two cameras, it is straightforward to convert these measurements into physical units (e.g., mm/s), thereby providing more meaningful insights. Moreover, the frame-by-frame tracking approach can lead to instability, especially due to occlusion or reflection overlap. To improve robustness, we plan to explore temporal tracking methods that incorporate information from multiple frames—such as smoothing techniques or Kalman filtering—in future studies.

Conclusions

The utilization of tracking techniques in an experimental setting to facilitate ecological observations is not without its inherent challenges. For instance, there is a potential for false positives resulting from reflections of organisms on the surface of the tank, as well as the possibility of misjudging the distance traveled due to parallax effects. In this study, we proposed a method to compensate for false positives in tracking using the YOLOv8 model. In instances where YOLO identifies multiple target objects at a given time, the distance between the coordinates of each detection result is calculated. The detection result that is in closest proximity to the coordinate that was specifically detected at time t-1 is then considered the true target object. This approach effectively prevents false detection due to reflections on the tank surface. When the image is captured at an angle perpendicular to the surface of the tank, the tank surface situated behind the tank appears to be smaller due to the phenomenon of parallax. If YOLO tracking is conducted in this manner, errors are introduced in the measurement of distances between the front and rear surfaces of the tank. Accordingly, the distance error resulting from the parallax effect was mitigated through the implementation of a barrel transformation in the horizontal direction, extending from the image’s center to its periphery. As a result, it was confirmed that the visual evaluation conducted by experts and the tracking results generated by YOLO were in general agreement. The proposed method proved effective in reducing judgment errors in organism tracking and enabled precise measurement of the distance, speed, and angle of movement of organisms in the aquarium. Future work will focus on extending this technique to more complex conditions, potentially involving multiple individuals or diverse environments. Through these refinements, the method may serve as a foundation for more detailed ecological studies on shrimp behavior. Future studies will systematically evaluate these corrective measures to clarify their effectiveness and refine the overall detection framework. Through these refinements, the method may serve as a foundation for more detailed ecological studies.

Data availability

The data used in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Donfouet, H. P. P., Barczak, A., Détang-Dessendre, C. & Maigné, E. Crop production and crop diversity in France: A spatial analysis. Ecol. Econ. 134, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.11.016 (2017).

Quijas, S. & Balvanera, P. Biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity 2nd edn (ed. Levin, S. A.) 341–356 (Academic Press, Waltham, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384719-5.00349-X.

Danley, B. & Widmark, C. Evaluating conceptual definitions of ecosystem services and their implications. Ecol. Econ. 126, 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.04.003 (2016).

Percy, S. et al. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Business and Industry Synthesis Team Synthesis Team Members Synthesis Team Co-chairs Business Council for Sustainable Development-Brazil World Business Council for Sustainable Development A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005).

Ito, K. et al. Spatial and economic quantification of provisioning service by eelgrass beds in Lake Notoro, Hokkaido, Japan. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 3742. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54348-7 (2024).

Costanza, R. et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387(6630), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0 (1997).

Cole, S. G. & Moksnes, P.-O. Valuing multiple eelgrass ecosystem services in Sweden: Fish production and uptake of carbon and nitrogen. Front Mar Sci https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2015.00121 (2016).

Plummer, M. L., Harvey, C. J., Anderson, L. E., Guerry, A. D. & Ruckelshaus, M. H. The role of eelgrass in marine community interactions and ecosystem services: Results from ecosystem-scale food web models. Ecosystems 16(2), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9609-0 (2013).

Rueda, J., Marina, P., Urra, J. & Salas, C. Effects of eelgrass loss on coastal biodiversity. JMBA Glob. Mar. Environ. 10, 12–13 (2009).

Leiva-Dueñas, C. et al. Capturing of organic carbon and nitrogen in eelgrass sediments of southern Scandinavia. Limnol. Oceanogr. 68(3), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.12299 (2023).

Azuma, N. et al. Isolation and characterization of 13 polymorphic microsatellites for the Hokkai Shrimp, Pandalus latirostris. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 3(3), 529–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12686-011-9396-5 (2011).

Bergström, B. I. The biology of Pandalus. In Advances in Marine Biology, Vol. 38, 55–245 (Academic Press, 2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2881(00)38003-8.

Castro-Santos, T., Haro, A. & Walk, S. A passive integrated transponder (PIT) tag system for monitoring fishways. Fish. Res. 28(3), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-7836(96)00514-0 (1996).

Føre, M. et al. Precision fish farming: A new framework to improve production in aquaculture. Biosyst. Eng. 173, 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2017.10.014 (2018).

Pekow, C. A. Chapter 10—Basic experimental methods in the rabbit. In The Laboratory Rabbit, Guinea Pig, Hamster, and Other Rodents (eds Suckow, M. A. et al.) 243–258 (Academic Press, Boston, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-380920-9.00010-9.

Read, A. J. T - Telemetry. In Encyclopedia of marine mammals 2nd edn (eds Perrin, W. F. et al.) 1153–1156 (Academic Press, London, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373553-9.00265-0.

Mei, Y. et al. Recent advances of target tracking applications in aquaculture with emphasis on fish. Comput. Electron. Agric. 201, 107335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2022.107335 (2022).

Rodríguez, Á., Bermúdez, M., Rabuñal, J. R. & Puertas, J. Fish tracking in vertical slot fishways using computer vision techniques. J. Hydroinform. 17(2), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.2166/hydro.2014.034 (2014).

Stewart, A. M., Gaikwad, S., Kyzar, E. & Kalueff, A. V. Understanding spatio-temporal strategies of adult zebrafish exploration in the open field test. Brain Res. 1451, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.064 (2012).

Suzuki, K., Takagi, T. & Hiraishi, T. Video analysis of fish schooling behavior in finite space using a mathematical model. Fish. Res. 60(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-7836(02)00081-4 (2003).

Delcourt, J., Denoël, M., Ylieff, M. & Poncin, P. Video multitracking of fish behaviour: A synthesis and future perspectives. Fish. Fish. 14(2), 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2012.00462.x (2013).

Salierno, J. D., Gipson, G. T. & Kane, A. S. Quantitative movement analysis of social behavior in mummichog, Fundulus heteroclitus. J. Ethol. 26(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-006-0027-7 (2008).

Kanbara M, Ukita N, Kidode M, & Yokoya, N. 3D scene reconstruction from reflection images in a spherical mirror. In 18th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR’06), 874–879 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPR.2006.32.

J. Matsumoto et al., “A 3D-Video-Based Computerized Analysis of Social and Sexual Interactions in Rats,” PLoS One, vol. 8, no. 10, pp. e78460-, Oct. 2013, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078460

Chen, Z., Wong, K.-Y. K., Liu, M., & Schnieders, D. Single-view reconstruction from an unknown spherical mirror. In 2011 18th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, 2677–2680 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP.2011.6116219.

Saberioon, M. M. & Cisar, P. Automated multiple fish tracking in three-dimension using a structured light sensor. Comput. Electron. Agric. 121, 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2015.12.014 (2016).

Horodysky, A. Z., Kerstetter, D. W., Latour, R. J. & Graves, J. E. Habitat utilization and vertical movements of white marlin (Tetrapturus albidus) released from commercial and recreational fishing gears in the western North Atlantic Ocean: Inferences from short duration pop-up archival satellite tags. Fish. Oceanogr. 16(3), 240–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2419.2007.00419.x (2007).

Al Muksit, A. et al. YOLO-Fish: A robust fish detection model to detect fish in realistic underwater environment. Ecol. Inform. 72, 101847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101847 (2022).

Xiao, P. et al. Yolo-AWD+CBT: An efficient algorithm for Micropterus salmoides swimming behavior analysis based on multi-object tracking. Aquaculture 595, 741554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741554 (2025).

Cachat, J. et al. Three-dimensional neurophenotyping of adult zebrafish behavior. PLoS ONE 6(3), e17597. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017597 (2011).

Han, B.-J. & Sim, J.-Y. Glass reflection removal using co-saliency-based image alignment and low-rank matrix completion in gradient domain. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 27(10), 4873–4888. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2018.2849880 (2018).

Qiu, J., Jiang, P.-T., Zhu, Y., Yin, Z.-X., Cheng, M.-M., & Ren, B. Looking through the glass: Neural surface reconstruction against high specular reflections. In 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 20823–20833 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01995

Yan, T., Li, H., Gao, J., Wu, Z. & Lau, R. W. H. Single image reflection removal from glass surfaces via multi-scale reflection detection. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 69(4), 1164–1176. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCE.2023.3303475 (2023).

Yamashita, A., Hayashimoto, E., Kaneko, T., & Kawata, Y. 3-D measurement of objects in a cylindrical glass water tank with a laser range finder. In Proceedings 2003 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2003) (Cat. No.03CH37453), Vol. 2, 1578–1583 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS.2003.1248869.

Ishihara, Y. & Ishihara, M. Peripheral distortion on views in a fish tank could be corrected using a trapezoidal glass and microlens array. In HCI International 2019—Posters (ed. Stephanidis, C.) 158–164 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019).

Ishihara, Y. & Ishihara, M. Correcting distortion of views into aquarium and its accuracy. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. E97(9), 2552–2553. https://doi.org/10.1587/transinf.2014EDL8092 (2014).

Ultralytics, Ultralytics YOLO docs. Accessed: Oct. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://docs.ultralytics.com/

Hussain, M. YOLOv1 to v8: Unveiling each variant–a comprehensive review of YOLO. IEEE Access 12, 42816–42833. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3378568 (2024).

Solawetz, J. What is YOLOv8? A Complete Guide. Accessed: Oct. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://blog.roboflow.com/what-is-yolov8/

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Susumu Chiba and Mr. Hiroyuki Matsumoto of the Tokyo University of Agriculture for securing the samples. We also thank Mr. Kaii Suezawa of Nishi-Abashiri Fishermen’s Association for his cooperation in the survey. Finally, we would also like to take this opportunity to thank the Abashiri Fisheries Science Center and Abashiri City Hall staff for their collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, N.O., S.K., and Y.Z.; Methodology, N.O., S.K., K.T., and S.W.; Software, N.O., S.K., K.T., and S.W.; Validation, N.O., A.N., and S.I.; Formal analysis, N.O., S.K., Y.Z.. Kenji.M., Kazushi.M., Y.M., and Y.K.; Investigation, N.O., and S.K.; Resources, S.K., Y.Z., A.N., S.I., Kenji.M., and Kazushi.M.; Data curation, S.K., A.N., and S.I.; Writing-original draft, N.O., S.K., and Y.Z.; Writing-review & editing, N.O., S.K., Y.Z., Y.O., Kenji.M, Kazushi.M., and Y.K.; Visualization, N.O.; Supervision, Y.Z., Y.O., Kenji.M, Kazushi.M., and Y.K.; Project administration, Y.Z., Kenji.M, and Kazushi.M.; Funding acquisition, Y.Z., Kenji.M, and Kazushi.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okada, N., Kubo, S., Zhu, Y. et al. Improving Hokkai shrimp tracking accuracy using YOLOv8 with reflection and parallax correction. Sci Rep 15, 29482 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01138-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01138-4