Abstract

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a prevalent cardiovascular disease, with increasing incidence and mortality rates associated with aging populations and rising rates of chronic diseases. Systemic inflammatory response is recognized to play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of CHF, and the aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI) has garnered widespread attention as a comprehensive indicator reflecting inflammatory status in recent years. However, there is currently a lack of large-scale epidemiological studies investigating the relationship between AISI and all-cause, cardiovascular, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality risks among CHF patients. This study aims to utilize data from the NHANES database spanning 1999 to 2018 to analyze the association between AISI and prognosis in CHF patients, aiming to provide new evidence to support research into the pathophysiology and clinical management of CHF. This study enrolled 1624 patients aged ≥ 18 years with congestive heart failure (CHF) from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey spanning 1999 to 2018. Patients were stratified into four groups based on the aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI). Survival differences among the groups were compared using log-rank tests and Kaplan-Meier curves. Additionally, multivariable Cox regression and restricted cubic spline analyses were employed to explore the relationship between AISI and all-cause, cardiovascular, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. Overall, during a mean follow-up of 76.4 ± 56.6 months among patients with congestive heart failure, a total of 828 participants (51.042%) died. Among these, 314 (19.389%) deaths were attributed to cardiovascular diseases, and 344 (21.226%) were related to cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed significant differences in all-cause, cardiovascular, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality among AISI quartiles (log-rank test: all P < 0.001). Multivariable adjusted models demonstrated that participants in the highest AISI quartile had increased risks of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.599, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.595–1.602), cardiovascular mortality (HR = 1.070, 95% CI 1.066–1.074), and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality (HR = 1.173, 95% CI 1.168–1.177) compared to those in the lowest quartile. Additionally, restricted cubic spline analysis indicated a nonlinear association between AISI and all-cause mortality (P = 0.0064), with an inflection point at AISI 8.66. On the left flank of the inflection point, each twofold increase in AISI was associated with a 19.6% higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 1.196, 95% CI 0.930–1.538), while on the right flank, there was a 126.2% increase (HR = 2.262, 95% CI 1.506–3.395). Furthermore, each twofold change in AISI was nonlinearly associated with a 60.2% higher risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR = 1.602, 95% CI 1.075–2.388) and a 56.6% higher risk of cardio-cerebrovascular mortality (HR = 1.566, 95% CI 1.072–2.286). E-value analysis suggested robustness to unmeasured confounding. In the population of patients with congestive heart failure aged 18 years and older in the United States, irrespective of established risk factors, AISI was significantly associated with all-cause, cardiovascular, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. Further research is needed to validate this.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congestive heart failure (CHF) affects over 60 million people globally and ranks among the leading causes of mortality in both developed and developing countries. In recent decades, CHF has emerged as a significant epidemic worldwide, particularly in Western nations where it is a primary contributor to death. CHF represents a late-stage complication of numerous cardiovascular diseases, characterized by a five-year mortality rate reaching 50% post-diagnosis. According to the American Heart Association (AHA), the prevalence of CHF is projected to increase by 46% from 2012 to 2030, with an annual addition of 960,000 new cases of CHF1.

The Aggregate Index of Systemic Inflammation (AISI) is a novel metric that integrates established inflammatory markers including neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, and platelets. This index is widely employed to assess the systemic inflammatory status across various diseases such as osteoporosis, obesity, and sarcopenia. Concurrently, alongside emerging indices like the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) and Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI), AISI has demonstrated significant potential in medical research2. Calculated as the ratio of neutrophils, monocytes, and platelets to lymphocytes, AISI comprehensively evaluates the severity of inflammation, providing a robust tool for prognostic assessment in diseases.

The Systemic Inflammation Aggregate Index (AISI: Neutrophils (NEU) * Platelets (PLT) * Monocytes (MONO) / Lymphocytes (LYM)) is a composite marker that comprehensively assesses the systemic inflammatory state based on whole blood cell counts, characterized by its ease of accessibility. AISI, as a novel prognostic biomarker, has garnered attention in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Studies have demonstrated its ability to significantly differentiate IPF patients from healthy subjects, with AISI levels independently associated with adverse prognosis. Additionally, AISI has been found to correlate significantly with poor outcomes in patients with viral pneumonia. However, research on the predictive value of AISI in congestive heart failure (CHF) prognosis remains limited. Therefore, this study aims to investigate whether AISI can independently predict the prognosis of CHF. Furthermore, we aim to assess the clinical significance of AISI in predicting all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cerebrovascular mortality in adult patients with congestive heart failure. Moreover, we plan to evaluate AISI as a cost-effective and readily accessible indicator for cardiovascular disease risk.

Methods

Study population

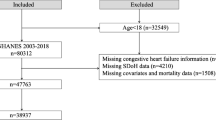

The study participants were derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study protocol was approved by the NCHS Ethics Review Board. NHANES is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of non-institutionalized civilian households in the United States. This large-scale ongoing probability survey is conducted biennially, forming a cycle every year. The study utilized data from 10 cycles of the NHANES dataset spanning from 1999 to 2018, involving a total of 101,317 participants. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) individuals aged under 18 years (n = 42,113); (b) individuals without congestive heart failure (n = 57,298); (c) individuals lacking data on peripheral lymphocyte, neutrophil, monocyte, and platelet counts (n = 281); (d) participants lost to follow-up (n = 1). Therefore, the final analysis included 1,624 participants. Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of participant selection for the study population.

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) was confirmed based on the MCQ questionnaire, which has been validated in previous studies for the effectiveness of self-reported heart failure. Participants were asked, “Has a doctor or other healthcare professional ever told you that you have heart failure?”

Exposure

The NHANES Laboratory/Medical Technologists Procedures Manual (LPM) outlines the procedures for collection and processing of blood specimens. Complete blood count (CBC) parameters were determined using the Coulter® method for counting and sizing, with automated mixing and dilution employed for sample processing. VCS technology was utilized for differential analysis of white blood cells (WBCs), employing simultaneous measurement of individual cell volume (V), high-frequency conductivity (C), and laser light scattering (S) to differentiate neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes. Platelet counts were determined by multiplying the Plt histogram by a calibration constant and expressed as n × 103 cells/µL. The Atherogenic Index of Serum (AISI) was calculated as (Neutrophils (NEU) * Platelets (PLT) * Monocytes (MONO)) / Lymphocytes (LYM).

Participants self-reported age, gender, race, smoking status, marital status, education level, and medical history (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, stroke, coronary heart disease, angina). Laboratory measurements such as creatinine (Cr), uric acid, triglycerides, and cholesterol were collected using automated blood analysis equipment. Detailed procedures for obtaining laboratory measurements are available on the NCHS website. Comorbidities were determined based on participants’ self-reported health diagnoses within the past 12 months.

Primary outcome

Detailed mortality status information derived from the NHANES-linked National Death Index records is available on the NCHS data linkage website. Primary outcomes include all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. Causes of death were classified according to the 10th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Cardiovascular mortality was classified using ICD-10 codes I00-I078. Mortality follow-up data were available through December 31, 2019, for participants in NHANES from 1999 to 2018.

Statistical analysis

We computed group-specific weights using the weights recommended by NHANES. Participants were stratified into four groups based on AISI quartiles: Q1 group 127.261 ± 41.889, Q2 group 252.119 ± 35.878, Q3 group 398.036 ± 54.999, and Q4 group 890.686 ± 459.379. Continuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviations, while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess differences among AISI quartiles in categorical or continuous variables. Kaplan–Meier plots and log-rank tests were used to determine differential survival rates for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality according to AISI quartiles.

Multivariate Cox regression models were employed to examine the relationship between AISI and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality, calculating hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, race, education, and marital status. Model 3 further adjusted for BMI, white blood cell count, lymphocyte count, monocyte count, segmented neutrophils, hemoglobin, platelet count, cholesterol level, triglyceride level, uric acid level, creatinine level, smoking status, coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, stroke, hypertension, high cholesterol level, and diabetes mellitus.

Restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression models were utilized to explore the nonlinear relationship between AISI (per two-fold change) and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. Threshold points for nonlinear relationships were determined using a two-piece Cox regression model. Gender-specific models were employed to further investigate the impact of AISI on mortality risk among men and women.

Statistical analyses were conducted using Empower(R) (X&Y Solutions, Inc., MA, USA) and Stata (version 14.0). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P-value < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of participants at baseline

Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics of 1624 participants with congestive heart failure included in this study. The participants had a mean age of 66.140 ± 13.471 years, with 52.557% being male. The mean follow-up period was 76.4 ± 56.6 months, during which a total of 828 participants (51.042%) died. Among these, 314 deaths (19.389%) were attributed to cardiovascular diseases, and 344 deaths (21.226%) were related to cardio-cerebrovascular causes. Most baseline variables showed statistical significance, except for gender, BMI, education level, cholesterol, triglycerides, history of coronary heart disease, stroke history, and hyperlipidemia (P < 0.05). Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated significant differences in AISI quartiles for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality (log-rank test: all P < 0.001). Multivariable adjusted models (Table 2) indicated that participants in the highest AISI quartile had increased risks of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.599, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.595–1.602), cardiovascular mortality (HR = 1.070, 95% CI 1.066–1.074), and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality (HR = 1.173, 95% CI 1.168–1.177) compared to those in the lowest quartile. Additionally, segmented Cox regression analysis results are presented in Table 3. AISI was log2-transformed to better fit the model due to its skewed distribution. The likelihood ratio test showed significant results (< 0.001) applicable to both the linear Cox regression model and the segmented regression model. Restricted cubic spline analysis revealed a nonlinear association between AISI and all-cause mortality (P = 0.0064), with a inflection point at AISI 8.66. On the left side of the inflection point, each twofold increase in AISI was associated with a 19.6% higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 1.196, 95% CI 0.930–1.538), while on the right side, there was a 126.2% increase (HR = 2.262, 95% CI 1.506–3.395). Furthermore, each twofold change in AISI was nonlinearly associated with a 60.2% higher risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR = 1.602, 95% CI 1.075–2.388) and a 56.6% higher risk of cardio-cerebrovascular mortality (HR = 1.566, 95% CI 1.072–2.286).

The association between AISI and cardiovascular mortality

The Kaplan-Meier curve (Fig. 2B) demonstrated a significant inverse relationship between AISI values and survival rates among cardiovascular disease patients (log-rank P < 0.0001). Upon adjustment for all covariates (Table 2), the highest quartile of AISI showed a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.070 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.066–1.074) for cardiovascular mortality. Restricted cubic spline analysis indicated a nonlinear association between AISI and cardiovascular mortality (non-linearity P = 0.1561; Fig. 3B). Table 3 illustrated that each twofold increase in AISI was associated with a 29% increase in the risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR = 1.29, 95% CI 0.93–1.79).

Restricted cubic spline curves of relations between AISI with all-cause (A), cardiovascular mortality (B) and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality (C). Analysis was adjusted for gender, age, race, education level, marital status, body mass index, white blood cell, lymphocyte, monocyte, segmented neutrophils, hemoglobin, platelet, cholesterol, triglycerides, uric acid, creatinine, smokers, coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, stroke, hypertension, high cholesterol level, diabetes mellitus. The solid and dashed lines symbolize the hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals, respectively.

The association between AISI and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality

In the Kaplan-Meier curve for cardio-cerebrovascular disease (Fig. 2C), higher AISI values were significantly associated with decreased survival rates (log-rank P < 0.0001). After adjustment for all covariates (Table 2), the highest quartile of AISI demonstrated a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.18 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.168–1.177) for cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. Figure 3C depicted a nonlinear association between AISI and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality (non-linearity P = 0.0941). Table 3 indicated that each twofold increase in AISI was linked to a 30% higher risk of cardio-cerebrovascular mortality (HR = 1.30, 95% CI 0.96–1.76).

Subgroup analysis

Table 4 displays the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for cardiovascular mortality among women in the medium and highest tertiles, which were 0.430 (0.428, 0.431) and 0.629 (0.625, 0.633), respectively. For men in the same tertiles, the HRs and 95% CIs for cardiovascular mortality were 1.351 (1.346, 1.356) and 1.401 (1.394, 1.408), respectively.

Furthermore, Fig. 4A illustrates a nonlinear relationship between AISI and all-cause mortality in women (non-linearity P = 0.0055) and men (non-linearity P = 0.0058). Figure 4B demonstrates a nonlinear association between AISI and cardiovascular mortality in women (non-linearity P = 0.1783) and men (non-linearity P = 0.1315). Finally, Fig. 4C indicates that higher AISI values are nonlinearly associated with increased risk of cardio-cerebrovascular mortality in both women (non-linearity P = 0.1312) and men (P = 0.09).

Restricted cubic spline curves of relations between AISI and mortality in different sex groups. (A) all-cause mortality; (B) cardiovascular mortality; (C) cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. Analysis was adjusted for gender, age, race, education level, marital status, body mass index, white blood cell, lymphocyte, monocyte, segmented neutrophils, hemoglobin, platelet, cholesterol, triglycerides, uric acid, creatinine, smokers, coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, stroke, hypertension, high cholesterol level, diabetes mellitus.

Sensitivity analysis

We explored the potential for unmeasured confounding between preoperative prescriptions and mortality by calculating E-value3.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate whether the systemic immune-inflammation index (AISI) could predict long-term outcomes in patients with congestive heart failure. Also this study explored the association between the aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI) and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF), using data from NHANES 1999–2018. Our findings reveal several significant implications for clinical practice and future research. The findings indicate that increasing AISI levels are significantly associated with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. There was a pronounced increase in mortality risk as AISI reached 8.66. Similar association patterns were observed in both women and men. Despite comparable associations with all-cause mortality between genders, men exhibited a stronger correlation with cardiovascular and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. Previous research has confirmed that gender differences in cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes are attributed to comprehensive genetic and hormonal variations between males and females.

Multiple studies have indicated that the Aggregate Index of Systemic Inflammation (AISI) is considered a promising predictive biomarker capable of assessing and predicting clinical outcomes across various health conditions. These investigations have demonstrated associations between AISI and conditions such as hypertension, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, thyroid nodules, severity and mortality of COVID-19, dry age-related macular degeneration, esophageal cancer, prostate cancer, acute coronary syndrome, and albuminuria. These findings underscore the potential role of AISI in diverse disease processes, offering a novel biomarker perspective for future clinical and epidemiological research4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

AISI and mortality risk

Our results demonstrate a clear correlation between increasing AISI levels and heightened mortality risk across all categories studied. Specifically, as AISI surpassed 8.66, the risk of all-cause mortality notably escalated. This underscores the potential utility of AISI as a prognostic biomarker in CHF, offering clinicians a quantitative tool to assess systemic inflammation and its implications for patient outcomes.

Gender-specific differences

Interestingly, while both male and female patients exhibited similar associations with all-cause mortality concerning AISI levels, males displayed a more pronounced correlation with cardiovascular and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality. This disparity suggests potential gender-specific biological factors influencing inflammation-mediated cardiovascular outcomes in CHF, which merits further investigation into genetic and hormonal influences.

Clinical implications

The identification of AISI as a predictor for adverse cardiovascular events in CHF patients has significant clinical implications. Monitoring AISI levels could aid in risk stratification, guiding personalized treatment strategies aimed at mitigating systemic inflammation and improving long-term outcomes. Interventions targeting inflammation, such as anti-inflammatory therapies or lifestyle modifications, may prove beneficial in reducing mortality rates among CHF patients with elevated AISI.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study benefited from the inclusion of 1624 patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) and extended longitudinal follow-up, allowing for an in-depth exploration of the aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI) and its relationship with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cerebrovascular mortality in this specific population. The study population in this article is not applicable to hospitalized individuals, outpatient or emergency care populations, children, or other countries. We utilized the RCS model to analyze the complex nonlinear relationships between AISI and these mortality outcomes. However, the study has several limitations. These include potential recall bias associated with self-reported complications and lifestyle data, as well as the limitation of only capturing baseline AISI values without reflecting changes during follow-up. Despite adjustments for multiple confounding factors, unaccounted variables may still impact the study outcomes. Future prospective research is needed to validate our findings and elucidate the mechanistic pathways linking systemic inflammation, AISI, and mortality in CHF. Additionally, investigating the impact of anti-inflammatory interventions on AISI dynamics and clinical endpoints could further enhance therapeutic strategies and understanding in this field. We used the E-value sensitivity analysis to quantify the potential implications of unmeasured confounders and found that an unmeasured comfounder was unlikely to explain the entirety of the treatment effect.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study provides compelling evidence supporting the role of AISI as a predictive marker for mortality risk in CHF patients. By integrating AISI assessment into clinical practice, healthcare providers can potentially enhance risk assessment and tailor management strategies to improve outcomes in this high-risk population.

This discussion synthesizes the implications of our findings, highlighting both the clinical relevance and avenues for future research, thereby contributing to the growing body of knowledge on inflammation-mediated outcomes in congestive heart failure.

Data availability

The data of this study are publicly available on the NHANES website.

Abbreviations

- AISI:

-

The aggregate index of systemic inflammation

- LPM:

-

Laboratory/Medical Technologists Procedures Manual

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- CHF:

-

Congestive Heart Failure

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease (CVD)

- IPF:

-

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- WBCs:

-

white blood cells

- AHA:

-

American Heart Association

- SII:

-

Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index

- SIRI:

-

Systemic Inflammation Response Index

References

Heidenreich, P. A. et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: A report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 145 (18), e876–e894. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001062 (2022). Epub 2022 Apr 1. PMID: 35363500.

Xia, Y. et al. Systemic immune inflammation index (SII), system inflammation response index (SIRI) and risk of All-Cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality: A 20-Year Follow-Up cohort study of 42,875 US adults. J. Clin. Med. 12 (3), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031128 (2023). PMID: 36769776; PMCID: PMC9918056.

Haneuse, S. VanderWeele TJ,Arterburn d.using the e-value to assess the potential effect of unmeasured confounding in observational studies.jama.2019:321(6):602–603 .https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.21554

Xiu, J. et al. The aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI): a novel predictor for hypertension. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1163900. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1163900 (2023). PMID: 37265570; PMCID: PMC10229810.

Zinellu, A. et al. The aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI): A novel prognostic biomarker in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Med. 10 (18), 4134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184134 (2021). PMID: 34575245; PMCID: PMC8466198.

Cao, C., Li, C., Li, X., Sun, W. & Wang, Y. Association of systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI) with thyroid nodules in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 23 (1), 251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-023-01509-w (2023). PMID: 37986076; PMCID: PMC10659038.

Piticchio, T. et al. Inflammatory profile assessment in a highly selected athyreotic population undergoing controlled and standardized hypothyroidism. Biomedicines 12 (1), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12010239 (2024). PMID: 38275410; PMCID: PMC10813236.

Zinellu, A., Paliogiannis, P. & Mangoni, A. A. Aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI), disease severity, and mortality in COVID-19: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 12 (14), 4584. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144584 (2023). PMID: 37510699; PMCID: PMC10381001.

Sannan, N. S. Assessment of aggregate index of systemic inflammation and systemic inflammatory response index in dry age-related macular degeneration: a retrospective study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 10, 1143045. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1143045 (2023). PMID: 37181369; PMCID: PMC10166806.

Wang, H. K. et al. Clinical usefulness of the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio and aggregate index of systemic inflammation in patients with esophageal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Cancer Cell. Int. 23 (1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-023-02856-3 (2023). PMID: 36707809; PMCID: PMC9881346.

Wang, L., Li, X., Liu, M., Zhou, H. & Shao, J. Association between monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio and prostate cancer in the U.S. Population: a population-based study. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 12, 1372731. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2024.1372731 (2024). PMID: 38645410; PMCID: PMC11026607.

Tuzimek, A., Dziedzic, E. A., Beck, J. & Kochman, W. Correlations between acute coronary syndrome and novel inflammatory markers (Systemic Immune-Inflammation index, systemic inflammation response index, and aggregate index of systemic inflammation) in patients with and without diabetes or prediabetes. J. Inflamm. Res. 17, 2623–2632. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S454117 (2024). PMID: 38707954; PMCID: PMC11067916.

Sun, L., Huo, X., Jia, S. & Chen, X. Association between the aggregate index of systemic inflammation and albuminuria: A Cross-Sectional study of National health and nutrition examination survey 2007–2018]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 55 (3), 671–679 (2024). Chinese. doi: 10.12182/20240560108. PMID: 38948283; PMCID: PMC11211792.

Ghobadi, H. et al. Role of leukocytes and systemic inflammation indexes (NLR, PLR, MLP, AISI, SIR-I, and SII) on admission predicts in-hospital mortality in non-elderly and elderly COVID-19 patients. Front Med (Lausanne). ;9:916453. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.916453. PMID: 36059829; PMCID: PMC9434555.

Shvartz, V. et al. The role of «novel» biomarkers of systemic inflammation in the development of early hospital events after aortic valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis. Life (Basel). 13 (6), 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13061395 (2023). PMID: 37374176; PMCID: PMC10303001.

Hamad, D. A. et al. Combined blood indexes of systemic inflammation as a mirror to admission to intensive care unit in COVID-19 patients: A multicentric study. J. Epidemiol. Glob Health. 12 (1), 64–73 (2022). Epub 2021 Dec 13. PMID: 34904189; PMCID: PMC8668150.

Chen, Y. et al. Systemic inflammation markers associated with bone mineral density in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. J. Inflamm. Res. 16, 297–309 (2023). PMID: 36713047; PMCID: PMC9879040.

Aydın, C. & Engin, M. The value of inflammation indexes in predicting patency of saphenous vein grafts in patients with coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Cureus 13 (7), e16646. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.16646 (2021). PMID: 34462681; PMCID: PMC8387011.

Magoon, R. et al. Atrial fibrillation and perioperative inflammation (FIBRILLAMMED Study): A Retrospective Analysis of the Predictive Role of Preoperative Albumin-Adjusted Platelet-Leukocytic Indices in OPCABG. Turk. J. Anaesthesiol. Reanim. 51 (4), 331–340 (2023). PMID: 37587676; PMCID: PMC10440484.

Huang, Y. W., Zhang, Y., Li, Z. P. & Yin, X. S. Association between a four-parameter inflammatory index and all-cause mortality in critical ill patients with non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage: a retrospective analysis of the MIMIC-IV database (2012–2019). Front. Immunol. 14, 1235266. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1235266 (2023). PMID: 37936706; PMCID: PMC10626529.

Zhao, X. et al. The association between systemic inflammation markers and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 24 (1), 334. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-024-04004-9 (2024). PMID: 38961330; PMCID: PMC11223271.

Saad, M. et al. Trends in cerebrovascular disease-related mortality among older adults in the united States from 1999 to 2020: an analysis of gender, race/ethnicity, and geographical disparities. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 34 (1), 108043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2024.108043 (2025). Epub 2024 Sep 26. PMID: 39341521.

Saeed, H. et al. Demographic trends and disparities in mortality related to coexisting heart failure and diabetes mellitus among older adults in the united States between 1999 and 2020: A retrospective population-based cohort study from the CDC WONDER database. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev. 23, 200326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcrp.2024.200326 (2024). PMID: 39282605; PMCID: PMC11395761.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the staff and participants of the NHANES study for their valuable contributions to this research. Additionally, we appreciate the invaluable contribution made by the Home for Researchers website.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province(2024JC-YBQN-0797).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BXF write the manuscript. CLL revise the manuscript. all authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics review board of the National Center for Health Statistics approved all NHANES protocols and written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, X., Cheng, L., Wang, H. et al. The aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI) and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality in congestive heart failure patients: results from NHANES 1999–2018. Sci Rep 15, 18282 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01196-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01196-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Joint association of estimated glucose disposal rate and aggregate index of systemic inflammation with mortality in general population: a nationwide prospective cohort study

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2026)

-

The association between the aggregate index of systemic inflammation and abdominal aortic calcification: a National health and nutrition examination survey

Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery (2025)

-

Relationship between aggregate index of systemic inflammation and mortality from CCD and malignant neoplasms in diabetic patients

Scientific Reports (2025)