Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) metastasis is driven, in part, by the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process critical for cancer cell migration and invasion. Current treatment options, including immunotherapies and targeted therapies, demonstrate limited efficacy in this aggressive disease, underscoring the need for innovative therapeutic approaches. Here, we present a novel approach integrating oncolytic virotherapy with RNA interference by engineering two variants of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSVd51) expressing pri- or pre-miR-199a-5p, a microRNA implicated in the regulation of EMT. We demonstrate that both viral constructs are functional and capable of overexpressing mature miR-199a-5p. In the human TNBC cell line MDA-MB-231, both viral variants inhibited the expression of ZEB1, a transcription factor central to EMT. However, in the mouse TNBC cell line 4T1, miR-199a-5p delivered via VSVd51 failed to disrupt EMT-related gene expression. In vivo testing of VSVd51-pre-miR-199 in the syngeneic BALB/c-4T1 mouse model revealed no significant survival benefits or reduction in tumor growth, even when coupled with primary tumor resection. Additional in vivo testing in immunodeficient mice using the MDA-MB-231 xenograft model showed no effect on tumor reduction. Our study highlights the challenges of integrating miRNA-based strategies with oncolytic viruses in a cancer context-specific manner and underscores the importance of vector selection and tumor model compatibility for therapeutic synergy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has become a target of immunotherapies due to its augmented immunogenicity compared to other breast cancer subtypes. The treatment regimen for advanced stages of TNBC includes the ICI pembrolizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting PD-1, but its efficacy remains limited, suggesting the need for more potent immunotherapies1. Despite the overall increase in survival of patient with breast cancer over the last decades, TNBC remains fatal in a significant proportion of cases. This can be attributed to its propensity to develop metastases more frequently and rapidly than other breast cancer subtypes2. Once metastases are detected, pathologic complete response at resection following neoadjuvant treatment is the best indicator of long-term survival3,4. Therefore, crafting immunotherapies that can promote a powerful immune response in situ while helping to target metastases could have good therapeutic potential for patients with advanced TNBC.

Oncolytic viruses (OV) are a type of viro-immunotherapy that can remodel the tumor microenvironment (TME) and elicit a strong antitumor immune response by selectively targeting and lysing tumor cells5. Their tumor tropism enables in situ delivery of genetically encoded therapeutic payloads, which has led to the development of OV with improved immunostimulatory properties and therapeutic efficacy. To this end, we have recently demonstrated the superiority of the oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus (VSVd51) expressing GM-CSF on reducing tumor growth and improving survival, in a murine model of bladder cancer, through enhanced activation of antitumor immunity6. VSVd51 is a potent inducer of the immune system and has been shown to promote antitumor immune responses in a variety of cancers, including TNBC. We have previously demonstrated the ability of a VSVd51-infected cell vaccine to remodel the systemic immune landscape in TNBC, in part through activation of CD8+T cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells. This led to long-term survival in the BALB/c-4 T1 model of mouse TNBC7,8. These studies highlight the strong antitumor immune response that can be generated by OV infection, directly or indirectly.

Metastasis relies on the migration and invasion of cancer cells, processes that are facilitated by the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). The transition into a migratory and invasive phenotype is regulated by transcription factors (TFs), namely SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, ZEB1, and ZEB2 in a context-dependent manner9,10. This can lead to the presence of hybrid epithelial-mesenchymal phenotypes induced by the expression of various combinations of TFs differentially expressed, as not all transitions follow the same morphogenic path11,12. Inflammation, hypoxia, and other cellular stresses as well as growth factors regulate the activity of TFs including ZEB1 that can reprogram cell identity and enable migration to distant tissues10,13. Interestingly, ZEB1 and other molecular regulators of EMT also have immunosuppressive functions in breast cancer14,15. Therefore, an immunotherapy targeting the EMT could inhibit metastases and reverse immunosuppression16.

These processes, and others, are regulated by microRNAs (miRNA, miR). MiRNAs are short non-coding interfering RNAs that regulate the post-transcriptional expression of multiple genes by targeting untranslated regions (UTR) of mRNAs. They are first transcribed as primary miRNAs (pri-miRNA) in the nucleus and exported into the cytoplasm after being processed into shorter precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) from which the mature miRNA is derived17. Their role in cancer is well established and justifies investigations into miRNAs as therapeutic molecules18. In breast cancer and TNBC subtypes, the miRNA miR-199a-5p (miR-199) has been associated with tumor-suppressive functions, inhibition of migration and invasion, and response to PD-L1 inhibitors19,20,21. Genes reported to be targeted by miR-199 include EMT-related genes, HIF1 A, and HSPA5, which are all involved in breast cancer, and TNBC progression19,22,23,24. However, a study by Turashvili et al.. correlated miR-199 expression with decreased overall survival in TNBC, highlighting gaps in our understanding of miR-199 function in TNBC and the difference between expression and overexpression25.

Recent studies have explored the therapeutic potential of combining OV with microRNAs to modulate tumor pathways and enhance immune responses26. For example, Wedge et al.. engineered VSVd51 to express artificial miRNAs targeting tumor resistance genes, demonstrating enhanced oncolysis and immune activation in melanoma and pancreatic cancer models27. Other reports have linked mir-199 to suppression of EMT and PD-L1 pathways in breast and lung cancers19,20,21,22. However, few studies have systematically evaluated miR-199 delivery via VSVd51 in the context of TNBC, particularly using both human and syngeneic mouse models. This represents a critical gap that our study addresses.

Despite encouraging in vitro data, many prior studies lack comprehensive in vivo validation across multiple TNBC models or fail to examine miRNA-mediated effects in the context of viral replication kinetics, immune evasion, or tumor microenvironment remodeling. Moreover, the compatibility of miRNA biogenesis with cytoplasmic virus replication is often assumed but remains poorly defined. To contribute to the field of TNBC viro-immunotherapy, we sought to test a novel VSVd51 overexpressing miR-199 in the syngeneic BALB/c-4 T1 mouse model of TNBC to simultaneously lyse cancer cells and inhibit the expression of genes involved in tumor migration, invasion, and immunosuppression. Specifically, we hypothesized that delivery of miR-199a-5p via VSVd51 could suppress EMT-promoting genes, such as ZEB1, SNAIL1, and HIF1 A, thereby reducing tumor invasiveness and enhancing the immunotherapeutic and oncolytic effects of the virus in TNBC models. Given the cytoplasmic nature of VSVd51 replication, we hypothesized that expressing pre-miR-199a-5p, which directly enters into the Dicer processing pathway would be more compatible with the viral lifecycle and therefore more efficient in producing mature miRNA and achieving gene silencing. In contrast, expression of pri-miR-199a-5p, which requires nuclear Drosha processing, might be less effective due to spatial mismatch between transcriptional output and miRNA biogenesis.

The main contributions of this study are:

-

We engineered two novel VSVd51 constructs expressing pri- and pre-miR-199a-5p and validated their expression and cytotoxicity in TNBC cell lines.

-

We demonstrated that pre-VSVd51-miR-199 partially suppresses EMT-related mRNA targets in human TNBC cells, but not in mouse cells.

-

We showed that the addition of miR-199 does not improve therapeutic outcomes over control virus in both immunocompetent and immunodeficient TNBC models.

-

We discuss the limitations of combining miRNAs with cytoplasmic OV backbones and suggest future directions to improve compatibility and efficacy.

Results

VSVd51 over-express miR-199 in TNBC cell lines

MiRNA expression is regulated by complex processes that are highly dependent on the exact sequence of nucleotides (nts) that is transcribed and the resulting secondary structure, which folds like a hairpin upon itself through partial self-complementarity17. Thus, we engineered two VSVd51 variants expressing each stage of miRNA maturation to evaluate efficacy: VSVd51 expressing pri-miR-199 (VSVd51-pri-miR-199) and VSVd51 expressing pre-miR-199 (VSVd51-pre-miR-199). The genetic sequence of MIR199 A1, the gene encoding miR-199 was collected from NCBI and constituted the pre-miR-199 transgene, 71 nts in length. To generate the pri-miR-199 sequence, we added 50 nts at the 5’ and 3’ end corresponding to the DNA sequence flanking MIR199 A1 in the hg38 genome assembly from the UCSC genome browser. We note that that the term “pri-miR-199” here refers to an engineered 171 nts sequence consisting of the canonical pre-miR-199 flanked by 50 nts on either side (Fig. 1a). While this does not reflect the full endogenous pri-miRNA length, it was designed to enhance nuclear Drosha processing while remaining compatible with viral genomic insertion. The OVs expressing miR-199 were compared to VSVd51-shNTC, which expresses a short hairpin RNA targeting GFP, and serves as a non-targeting, negative control (shNTC) for viral infection.

VSVd51 over-express miR-199 in TNBC cell lines. (a) Graphical representation of VSVd51 expressing pri-miR-199a-5p or pre-miR-199a-5p. The transgene is inserted between VSV-G and VSV-L. To design VSVd51-pri-miR-199, the sequence of MIR199 A1 was flanked by 50 nucleotides (nts) corresponding to the genomic DNA (gDNA) sequence upstream and downstream of the MIR199 A1 gene. (b) Cellular viability (MTT assay) of 4 T1 cells following infections with 10−5 to 101 plaque forming units per cells (MOI). (c) Quantification of relative miR-199 expression (stem-loop qPCR) in 4 T1 cells infected with VSVd51-pri-miR-199 (V1) or VSVd51-pre-miR-199 (V2) presented as fold increase. (d) Cellular viability (MTT assay) of MDA-MB-231 following infections with 10−5 to 101 plaque forming units per cells (MOI). (e) Quantification of relative miR-199 expression (stem-loop qPCR) in MDA-MB-231 cells infected with VSVd51-pri-miR-199 (V1) or VSVd51-pre-miR-199 (V2) presented as fold increase.

Evaluation of cytotoxicity after genetic modification is essential to ensure OV functionality. Therefore, we performed cell viability assays following viral infection at various multiplicity of infection (MOI), a ratio of plaque forming units (pfu) to cancer cells, ranging from 10−5 to 101 in mouse 4 T1 (Fig. 1b) and in human MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 1d) TNBC cell lines. These results show that the viral constructs retained cytotoxic potency across both mouse and human TNBC cell lines, highlighting their use as functional platforms for transgene delivery. Next, to validate the functionality of VSVd51-pri-miR-199 and VSVd51-pre-miR-199, we quantified the relative overexpression, or fold increase, of miR-199 after infection in 4 T1 and MDA-MB-231 cells. We observed that both viruses induced overexpression of miR-199 in each of the TNBC cell line tested, with a trend towards elevated levels of miR-199 over-expression by VSVd51-pre-miR-199 infection (Fig. 1c and e). However, this result is not statistically significant. Together, these data demonstrate the functionality of our novel OVs, by measuring their cytotoxicity and validating the expression of their inserted transgenes.

VSVd51-miR-199 does not inhibit EMT-related gene expression in the 4 T1 TNBC cell line

4 T1 is a mouse stage IV TNBC cell line that is associated with invasion, migration, and metastasis through mechanisms relying on the EMT28. Prior to in vivo testing of our novel OV, we aimed at validating the ability VSVd51-pri-miR-199 and VSVd51-pre-miR-199 to silence its predicted target genes by qPCR in vitro. We selected to quantify Hspa5, Map3k11, Hif1a, and Ets1, four genes predicted to be targeted by miR-199 in mouse and experimentally validated in human cells20,22,23,24,29. We compared the expression of these four predicted targets in VSVd51-pri-miR-199- and VSVd51-pre-miR-199-infected 4 T1 cells to samples infected with the control OV VSVd51-shNTC. No statistically significant differences were observed between these conditions (p-value (p) > 0.05), suggesting that miR-199 expressed by VSVd51 cannot effectively inhibit the expression of these genes (Fig. 2a). We additionally quantified the expression of Snai1 and Twist1, two important EMT TFs. The latter was shown to be regulated by ectopic expression of miR-199 in the human MDA-MB-231 TNBC cell line, which warranted its addition to our panel of potential mouse target genes19. However, our analyses revealed that the expression of both Snai1 and Twist1 was not specifically inhibited by either virus (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, OV infection upregulated the expression of Twist1 (p = 0.0198) and downregulated the expression of Ets1 (p = 0.0018) and Snai1 (p = 0.0020), independent of miR-199 (Fig. 2a and b, Supplementary Fig. S1). Lastly, E-cadherin (Cdh1) and Vimentin (Vim) are markers of epithelial and mesenchymal states, respectively. Thus, they were used to assess potential effects of VSVd51-miR-199 infection on 4 T1 cells. The expression of Cdh1 and Vim was not altered by miR-199 expressing VSVd51 (Fig. 2c). Together, these results suggest that VSVd51-pri-miR-199 and VSVd51-pre-miR-199 do not inhibit the expression of the selected EMT-related genes in vitro.

VSVd51-miR-199 does not inhibit EMT-related gene expression in the 4 T1 TNBC cell line. Relative mRNA quantification (qPCR) of (a) Hspa5, Hif1a, Map3k11, and Ets1 (Top, left to right) and (b) Snai1, Twist1, (c) Cdh1, and Vim (Bottom, left to right). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (ns p > 0.05, * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01).

VSVd51-miR-199 does not reduce tumor growth, nor improve survival in the BALB/c-4 T1 TNBC mouse model

Considering the number of genes potentially targeted by miR-199 that are excluded from our qPCR analysis, which might mask the potential impact of miR-199, we proceeded to test VSVd51-pre-miR-199 in vivo using the BALB/c-4 T1 mouse model. We chose to test only VSVd51-pre-miR-199 because it produced miR-199 at slightly higher rates, albeit not significantly so, in both cell lines (Fig. 1c and e). To do so, we orthotopically implanted immune competent BALB/c mice with 1 × 105 4 T1 cells in the third mammary fat pad. At day 6, tumors in each group averaged around 50 mm3 and treatments began. Intratumoral (IT) injections of 5 × 108 pfu/ml per dose were administered to 12 mice per treatment cohort (VSVd51-shNTC and VSVd51-miR-199). Four doses were administered, 1 day apart, from day 6 to day 9 post-implantation, after which tumor volumes were measured 3 times a week until end point (Fig. 3a). The tumor growth observed in mice from both treatment cohorts were similar throughout the experiment, as reflected by the tumor volume of individual mice (Fig. 3b). Experimental end points were reached between day 22 and 36 to produce similar survival curves from both groups (Fig. 3e). Together, these results suggest that VSVd51-miR-199 does not reduce tumor growth or improve survival. However, when comparing the averaged tumor volumes, we noticed that the volume of tumors treated with VSVd51-miR-199 were lower than those treated with VSVd51-shNTC, at approximately day 19, but with a p-value of 0.0792, which is outside the limit of statistical significance (647.15 vs. 938.99 mm3 (Fig. 3c and d). This suggests a possible partial biological activity of miR-199 in a subset of animals. However, this effect was ultimately overshadowed by the rapid progression of 4 T1 primary tumors.

VSVd51-miR-199 does not reduce tumor growth, nor improve survival in the BALB/c-4 T1 TNBC mouse model. (a) Experimental timeline. (b) Individual tumor volumes of mice treated with VSVd51-shNTC (black) or VSVd51-miR-199 (grey). (c) Average tumor volumes of mice treated with VSVd51-shNTC (black) or VSVd51-miR-199 (grey). Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (ns p > 0.05). (d) Tumor volume of mice at day 19 post-implantation. Unpaired t test (ns p > 0.05). (e) Kaplan-Meier curves representing survival odds across time of mice treated with VSVd51-shNTC (n = 12) or VSVd51-miR-199 (n = 12). Log-rank Mantel-Cox test (ns p > 0.05). Note that panels b-e display complementary views of tumor growth and survival: individual trajectories (b), group averages over time (c), endpoint volume comparison (d), and survival.

Neoadjuvant VSVd51-miR-199 does not improve survival the BALB/c-4 T1 mouse model of TNBC

In human TNBC patients, surgical resection is standard-of-care and is often combined with neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy3,4. Given the well documented aggressive nature of the 4 T1 mouse model, we decided to combine VSVd51-miR-199 treatment with a primary tumor resection before day 19 to recapitulate a clinically relevant treatment context and to provide a larger treatment window. Therefore, we repeated the previous in vivo experiment while adding a primary tumor surgical resection 3 days after the last dose of OV (Fig. 4a). As expected, primary tumor resection increased survival in our model of advanced TNBC, which agrees with previous reports30. However, treatment with VSVd51-miR-199 did not further improve survival compared to VSVd51-shNTC treated cohort (Fig. 4b). This data suggests that VSVd51-miR-199 administered in the neoadjuvant period, does not enhance survival in the BALB/c-4 T1 TNBC model.

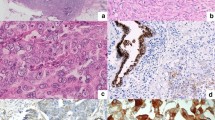

ZEB1 mRNA, but not protein expression is significantly reduced by VSVd51-miR-199 in the human MDA-MB-231 TNBC cell line

MDA-MB-231 is a human late-stage TNBC cell line that exhibit increased invasiveness in vitro and high metastatic potential in vivo when used in xenograft models31. The EMT contributes to this phenomenon and can be targeted to inhibit invasion and metastasis in the MDA-MB-231 model16. It is therefore an ideal model to evaluate the capacity of miR-199 overexpressed by VSVd51 to modulate EMT-related gene expression. ZEB1, MLK3 (Map3k11) and GRP78 (Hspa5) are targets of miR-199 predicted by publicly available bioinformatical tools (TargetScan, targetscan.org; MiRDB, mirdb.org) and experimentally validated19,23,24,29. MLK3 appears high on the list of predicted targets and therefore was selected to highlight gene silencing by miR-199. MLK3 has also been linked with the EMT to promote breast cancer cell invasion, migration, and metastasis32,33. As for GRP78, multiple studies have demonstrated its inhibition by miR-19923[,24. GRP78 is a master regulator of the unfolded protein response pathway and plays a critical role in the proliferation, migration, and invasion of cancer cells34,35. Thus, we proceeded to infect MDA-MB-231 cells with either VSVd51-shNTC, VSVd51-pri-miR-199 or VSVd51-pre-miR-199, and quantified protein expression after 48 h. Our results show that infection with VSVd51-miR-199 does not inhibit the protein expression of ZEB1, GRP78 or MLK3 (Fig. 5a and b, Supplementary Fig. S2). We next sought to quantify mRNA as a more sensitive method for detection of gene silencing. Following total RNA extraction, we detected a significant decrease in the relative expression of ZEB1 mRNA in MDA-MB-231 cells infected with VSVd51-pri-miR-199 (p = 0.0182) or VSVd51-pre-miR-199 (p = 0.0122) (Fig. 5c). These results suggest that ZEB1 is differentially regulated by VSVd51-miR-199 in the human MDA-MB-231 TNBC cell line.

Zeb1 mRNA, but not protein expression is significantly reduced by VSVd51-miR-199 in the human MDA-MB-231 TNBC cell line. (a) Quantification of ZEB1, GRP78, and MLK3 relative protein expression (Western Blot) in MDA-MB-231. (b) Representative Western blot (cropped, full blot images in Supplementary Fig. S2) of whole-cell protein extract from non-infected control MDA-MB-231 (1) and infected with VSVd51-shNTC (2), VSVD51-pri-miR-199 (3), and VSVd51-pre-miR-199 (4) (c) Relative mRNA quantification (qPCR) of ZEB1 in MDA-MB-231. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (ns p > 0.05; * p ≤ 0.05).

VSVd51-miR-199 does not reduce tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model of TNBC

The human MDA-MB-231 cell line was implanted in immunodeficient Nude mice to promote tumor cell establishment and treated with either PBS (n = 5) as controls, VSVd51-shNTC (n = 10), or VSVd51-pre-miR-199 (n = 11). Treatment began on day 14 and 3 doses were given, at 3-day intervals (d14, d17, d20) (Fig. 6a). Tumor growth was then monitored for up to 50 days. While OV-treated mice exhibited reduced tumor growth (VSVd51-shNTC, p = 0.0388; VSVd51-miR-199, p = 0.0124), there was no difference in average tumor growth between mice treated with VSVd51-shNTC and mice treated with VSVd51-pre-miR-199 (Fig. 6b and c). Taken together, this data suggests that VSVd51-miR-199 does not play a significant role in reducing tumor volume in the xenograft MDA-MB-231 mouse model of TNBC.

VSVd51-miR-199 does not reduce tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model of TNBC. (a) Experimental timeline. (b) Individual tumor volumes of mice treated with PBS (dark), VSVd51-shNTC (grey), or VSVd51-miR-199 (dark grey). (c) Average tumor volume of mice treated with PBS (n = 5), VSVd51-shNTC (n = 10), or VSVd51-miR-199 (n = 11). Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (ns p > 0.05, * p ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

Our study explored the potential of VSVd51 as a live, replicating vector for delivering the tumor-suppressor miRNA miR-199 in TNBC models, combining viral oncolysis with RNA interference. VSVd51 replicates in the cytosol, where pre-miRNAs are exported, processed, and loaded onto Argonaute proteins, potentially facilitating miRNA function17,36. This colocalization may explain the superior overexpression of miR-199 by VSVd51-pre-miR-199 compared to VSVd51-pri-miR-199, although this difference was not statistically significant. In addition, our use of a shortened pri-mRNA may have limited processing efficiency. Future constructs may benefit from including longer upstream and downstream sequences or incorporating native promoter elements. Despite this, our findings revealed that the addition of miR-199 did not enhance therapeutic efficacy beyond VSVd51-mediated oncolysis alone. Interestingly, infection with VSVd51-shNTC alone led to downregulation of ETS1 and SNAIL1 and upregulation of TWIST1. This may reflect OV-induced stress responses or non-specific immunomodulation, consistent with prior reports37,38,39. We did observe a 2-fold decrease in ZEB1 mRNA expression in MDA-MB-231 cells infected with VSVd51-pre-miR-199 (p = 0.0122), although this did not translate to a significant reduction at the protein level. This could be due to high protein stability or insufficient duration of exposure to elicit post-transcriptional depletion. This finding highlights the need to account for kinetic delays and miRNA potency when interpreting downstream effects. From in vivo studies, tumor volumes in BALB/c-4 T1 model at day 19 were 647.15 mm3 (VSVd51-miR-199) versus 938.99 mm3 (control), nearing but not reaching statistical significance (p = 0.0792). These findings support the presence of modest biological activity, but underscore the need for more robust target engagement to yield therapeutic benefit.

One explanation for these null findings is the incomplete overlap between human and mouse miR-199 targets, despite their identical mature sequences. For instance, miR-199 has been reported to regulate human HSPA5, HIF1 A, MAP3 K11, and ETS1, which are involved in stromal remodelling and hypoxia responses. Modulation of these pathways may affect not only EMT, but also viral dissemination through the tumor. Additionally, by modulating the unfolded protein response and GRP78 levels, miR-199 may influence tumor susceptibility to viral stress and lysis. These context-dependent interactions between miR-199, the tumor microenvironment, and viral adaptability merit further investigation in future mechanistic studies. However, these targets were not significantly modulated in 4 T1 cells, and this was mirrored in the corresponding syngeneic mouse model. Similarly, while miR-199 inhibited ZEB1 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells, the effect was limited to mRNA suppression and did not result in sufficient protein depletion to outpace VSVd51 oncolysis. This indicates that the tumor-suppressive impact of miR-199 may not be fully compatible with the rapid cytotoxic activity of VSVd51 in TNBC. Further research should broaden the scope of cell lines, in vitro methods tested, and models tested to include diverse phenotypes. Although, miR-199 did not significantly suppress most EMT targets in vitro, we proceeded with in vivo testing based upon on prior studies showing its therapeutic potential and observed trends in our dataset. Future efforts will emphasize additional functional in vitro validation, including cell migration and invasions assays. Furthermore, future animal models could include immunodeficient mice to enable in vivo testing with other human breast tumor cell lines, such as MCF7 (albeit not TNBC), which has been previously to be regulated by miR-19919

The subcellular compartmentalization of miRNA biogenesis (nuclear processing of pri-miR versus cytoplasmic viral replication) may reduce the efficiency of endogenous pri-miR-199 processing. Even for pre-miR-199, limited Dicer accessibility or suboptimal strand loading onto RISC complexes may further attenuate gene silencing. The differential effects seen between cell lines also likely reflect context-specific miRNA machinery activity and target gene expression levels. Moreover, we will use synthetic miR-199 and scrambled control constructs in future studies to further validate the specificity of miRNA-mediated effects independent of viral delivery.

The limited literature on miR-199 in breast cancer underscores the need for further investigation. Existing studies primarily highlight its role in regulating migration and invasion through the suppression of ETS1, ZEB1, and TWIST1 in MDA-MB-231 cells19,20. However, other reports suggest potential therapeutic relevance in immune regulation. For instance, miR-199 may counteract resistance to anti-PDL1 immunotherapy in 4 T1 models by targeting pathways involving DNMT1 and PDL1 expression21. Such findings emphasize the diverse context-dependent effects of miR-199 across cancer types, including hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and colorectal cancer22. Given the modest results observed with miR-199 in our study, alternative approaches should be explored. Oncolytic vectors such as vaccinia, herpes simplex, or adenovirus may provide better compatibility for miRNA delivery and enable broader therapeutic applications. One limitation of our study is the lack of viral replication or interferon (IFN) response quantification in tumor tissues. Future experiments examining the immunomodulatory effects could assess viral titres post-injection, and whether VSVd51-miR-199 alters interferon stimulated gene or IFNβ expression, antigen presentation pathways, immune checkpoint molecule regulation, and immune evasion in the tumor microenvironment.

Notably, recent studies have demonstrated the potential of artificial miRNAs tailored for compatibility with OV. For example, Wedge et al.. designed a VSVd51 expressing artificial miRNAs that improved tumor growth control and survival by depleting target genes critical for resistance to viral oncolysis27. Incorporating similar methodologies, such as screening for miRNAs that enhance VSVd51 replication and oncolysis, could improve therapeutic outcomes. Artificial miRNAs offer flexibility in targeting specific gene networks, potentially overcoming the limitations of endogenous miRNAs like miR-199.

Lastly, the immunosuppressive role of ZEB1, linked to the promotion of PDL1, CD47, and M2 macrophage polarization, makes it an attractive target in cancer immunotherapy14 Studies have also shown its role in reducing CD8+ T cell infiltration and driving immune evasion40 However, miRNAs from the miR-200 family may target ZEB1 more effectively than miR-199. Designing VSVd51 vectors expressing miR-200 family members could provide more robust suppression of Zeb1 and improve therapeutic efficacy in select cancers41.

This work highlights the challenges of developing miRNA-armed OV and underscores the importance of model-specific optimization in preclinical therapeutic strategies for TNBC. While therapeutic outcomes were limited, these data reveal biological constrains in current delivery strategies that can inform future engineering approaches. Our findings suggest that while miR-199 has potential as a tumor suppressor, VSVd51 may not be the optimal vector to unlock its therapeutic efficacy in TNBC models. Future studies should focus on identifying miRNAs inherently compatible with VSVd51 or other OV backbones as described above.

Artificial intelligence-based image analysis and patient stratification tools to better predict which TNBC phenotypes are most amenable to miRNA-based OV therapy could also be envisaged. For example, approaches such as a convolutional residual network for skin cancer classification and transfer learning for medical imaging could be adapted to TNBC lesion characterization42,43,44. Additionally, integrating omics-guided feature selection systems may aid in identifying molecular signatures of viral responsiveness45.

The translation of miRNA-armed OV therapy to the clinic may face several hurdles, including off-target effects due to miRNA promiscuity, heterogeneity in miRNA processing across tumors, and immune clearance of viral vectors. Patient-derived xenograft models may help evaluate these translational barriers, as they more faithfully recapitulate patient tumor heterogeneity and microenvironmental complexity. Ultimately, combining personalized gene therapy approaches with OV offers a promising avenue to synergistically target cancer-related genes and trigger potent viral oncolysis.

Materials and methods

Cell line and viruses

4 T1 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines were cultured in RPMI and DMEM respectively and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100U/ml penicillin, and 100ug/ml streptomycin. The 4 T1 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines were selected based on their well-characterized aggressive phenotypes and prior documentation of EMT-related behavior and oncolytic virus sensitivity. 4 T1 is a metastatic murine TNBC line used in syngeneic immunocompetent models, while MDA-MB-231 is a human basal-like TNBC line commonly used in xenograft and EMT studies31,46. Cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination and exhibited appropriate morphology at time of use. Stojdl et al. described the method used to engineer and rescue viruses47. Briefly, miRNA-encoding oligonucleotides purchased from IDT (Coralville, Iowa) were cloned into the VSVd51 empty vector through enzymatic digestion (XhoI/NheI) and ligation. The resulting plasmids were used to rescue viral particle, as described here27. All infections were carried out in serum-free RPMI or DMEM media for 1 h after which media was replaced with complete RPMI or DMEM. OV were propagated on Vero cells and purified using Opti-Prep purification methods. Viral titers were determined by a standard plaque assay following a previously published protocol48.

Cell viability

Viral cytotoxicity was measured indirectly through the assessment of cellular viability using the CellTiter 96 Non-radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega), a variant of the MTT assay method, following OV infection, in 96-well TC-treated plates.

Quantification of miRNAs and qPCR

Cells were washed in cold PBS and snap-frozen in TRIzol (#15596026, Invitrogen) prior to RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated using Direct-zol RNA Miniprep (#R2050, Zymo Research) per manufacturer’s instructions with DNAse I treatment. Reverse transcription was then performed using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (#205311, Qiagen). For qPCR experiments, primers were designed using Primer-Blast (NCBI) to span exon-exon junctions as to not amplify potential remnants of gDNA contamination and using the OligoAnalyzer Tool from IDT to minimize secondary structure formation49. They were then validated for specificity and efficiency using the standard curve method50. The Advanced qPCR Mastermix LO-ROX (#800-431-UL, Wisent) was used to perform qPCR on the LightCycler 96 (Roche). MiR-199 was quantified using the stem-loop qPCR method as previously described and performed by the RNomics platform at the Université de Sherbrooke51. Relative expression was determined by calculation of the ddCT and three selected housekeeping genes (HKGs) were used as references [human: miR-126-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-16-5p; mouse: RNU6, miR-222-3p, miR-16-5p] for miRNA quantification52. Expression of the non-targeting shNTC RNA was used as a control to normalize against miRNA-independent viral effects. For qPCR experiments, at least three selected HKGs were used as references [human: GAPDH, PUM1, RPL13 A; mouse: Gusb, Mrpl39, Pgk1, Pum1]. All qPCR primers are listed here (Supplementary Table S1).

Western blots

Whole cell lysates were generated using the RIPA lysis buffer formulation and protein concentrations were measured using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (#23225, Thermo Fisher). Antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies [GRP78 (BIP), #3177; MLK3, #2817; Zeb1, #70512] or Sigma [ACTb, #A2228]. Actin beta was used to normalize protein expression. Images were acquired with the Azure western blot imaging system C280 (Azure Biosystems) and band intensity was quantified with Image Studio Lite (LI-COR Biosciences).

Mice

Female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) and J: Nu outbred athymic mice (007850, 7 weeks old) were purchased from Charles Rivers (Quebec, Canada) and The Jackson Laboratory (Maine, USA) respectively. Animals were housed in pathogen-free conditions at the Cancer Research Institute of the Université de Sherbrooke with free access to food and water. Animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation under anesthesia. All studies were performed in accordance with Université de Sherbrooke guidelines and the Canadian Council on Animal Care. The animal ethics protocol (#2020–2606, #2024–4320) was approved by the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Animal Care Committee.

Orthotopic mouse models

4 T1 syngeneic mouse model of metastatic TNBC

We have previously established a female BALB/c mouse model of spontaneous and aggressive lung metastasis and surgical resection of primary TNBC tumors7. The experiment begins with the implantation of 1 × 105 4 T1 cells diluted in 100 uL of PBS injected orthotopically into the third left mammary fat pad. Intratumoral (IT) OV treatment began on day 6 with tumors of approximately 50 mm3 in volume, as measured with a Vernier caliper and calculated with the following formula: width*length*length/2. Four consecutive doses of OV were administered IT 1 day apart (day 6, 7, 8, 9) and, when indicated, complete resection of the primary tumor was performed 3 days after last treatment (day 12). This required mice to be kept under anesthesia for the duration of the procedure [3% induction, 2% maintenance of isoflurane with 2% oxygen]. Mice received a subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine [0.05 mg/kg] and saline [approx. 500 ul], and a peritumoral injection of lidocaine hydrochloride [7 mg/kg] and bupivacaine [3–5 mg/kg] to manage pain and prevent dehydration.

MDA-MB-231 xenograft mouse model of TNBC

The third mammary fat pad of J: Nu outbred athymic (Nude) mice was implanted with 2 × 106 MDA-MB-231 cells diluted (50ul) in equal parts of Matrigel (Corning) and DMEM. Treatments began 14 days after implantation, when tumors had grown to approximately 60 mm3. Three doses of PBS or OV were given with 2 days rest between each dose. Tumors were measured and mice were weighed twice each week until day 50.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad v10). Experiments were repeated at least 3 times, except for the qualitative assessment of miR-199 transgene expression. An unpaired t test was performed to compare tumor volumes of mice from different treatment regimen at end point. One-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used to analyze qPCR and western blot data involving three or more groups. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s correction was used for tumor volume comparisons over time. Kaplan-Meier curves were compared statistically using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Data is presented as mean ± standard error (SEM) unless otherwise indicated. All p-values were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05, and is represented as ns p > 0.05, * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001 and **** p ≤ 0.0001.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abdou, Y. et al. Immunotherapy in triple negative breast cancer: beyond checkpoint inhibitors. NPJ Breast Cancer. 8, 121 (2022).

Zagami, P. & Carey, L. A. Triple negative breast cancer: pitfalls and progress. NPJ Breast Cancer. 8, 95 (2022).

Han, H. S. et al. Early-Stage Triple-Negative breast Cancer journey: beginning, end, and everything in between. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educational Book. 43, e390464 (2023).

Leon-Ferre, R. A. & Goetz, M. P. Advances in systemic therapies for triple negative breast cancer. BMJ 381, e071674 (2023).

Achard, C. et al. Lighting a fire in the tumor microenvironment using oncolytic immunotherapy. EBioMedicine 31, 17–24 (2018).

Rangsitratkul, C. et al. Intravesical immunotherapy with a GM-CSF armed oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus improves outcome in bladder cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 24, 507–521 (2022).

Niavarani, S. R., Lawson, C., Boudaud, M., Simard, C. & Tai, L. H. Oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus–based cellular vaccine improves triple-negative breast cancer outcome by enhancing natural killer and CD8 + T-cell functionality. J. Immunother Cancer. 8, e000465 (2020).

Niavarani, S. R. et al. Heterologous prime-boost cellular vaccination induces potent antitumor immunity against triple negative breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 14, 1098344 (2023).

Dongre, A. & Weinberg, R. A. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 69–84 (2019).

Mittal, V. Epithelial mesenchymal transition in tumor metastasis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 13, 395–412 (2018).

Pastushenko, I. & Blanpain, C. EMT transition States during tumor progression and metastasis. Trends Cell. Biol. 29, 212–226 (2019).

Revenco, T. et al. Context dependency of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal transition for metastasis. Cell. Rep. 29, 1458–1468e3 (2019).

Grasset, E. M. et al. Triple-negative breast cancer metastasis involves complex epithelial-mesenchymal transition dynamics and requires vimentin. Sci. Transl Med. 14, 7571 (2022).

Guo, Y. et al. Zeb1 induces immune checkpoints to form an immunosuppressive envelope around invading cancer cells. Sci. Adv. 7, 7455–7476 (2021).

González-Martínez, S. et al. Epithelial mesenchymal transition and immune response in metaplastic breast carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7398 (2021).

Garcia, E. et al. Inhibition of triple negative breast cancer metastasis and invasiveness by novel drugs that target epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Sci. Rep. 11, 11757 (2021).

Treiber, T., Treiber, N. & Meister, G. Regulation of MicroRNA biogenesis and its crosstalk with other cellular pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5–20 (2019).

Kim, T. & Croce, C. M. MicroRNA: trends in clinical trials of cancer diagnosis and therapy strategies. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 1314–1321 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. miR-199a-5p confers tumor-suppressive role in triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 16, 887 (2016).

Li, W. et al. miR-199a-5p regulates Β1 integrin through Ets-1 to suppress invasion in breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 107, 916–923 (2016).

Wang, Q. et al. LncRNA TINCR impairs the efficacy of immunotherapy against breast cancer by recruiting DNMT1 and downregulating MiR-199a-5p via the STAT1–TINCR-USP20-PD-L1 axis. Cell. Death Dis. 14, 76 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Overview of microRNA-199a regulation in cancer. Cancer Management and Research vol. 11 10327–10335 Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S231971

Ahmadi, A., Khansarinejad, B., Hosseinkhani, S., Ghanei, M. & Mowla, S. J. miR-199a-5p and miR-495 target GRP78 within UPR pathway of lung cancer. Gene 620, 15–22 (2017).

Su, S. F. et al. miR-30d, miR-181a and miR-199a-5p cooperatively suppress the Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone and signaling regulator GRP78 in cancer. Oncogene 32, 4694–4701 (2013).

Turashvili, G. et al. Novel prognostic and predictive MicroRNA targets for triple-negative breast cancer. FASEB J. 32, 5937–5954 (2018).

St-Cyr, G. et al. Remodeling the tumor immune microenvironment with oncolytic viruses expressing miRNAs. Front. Immunol. 13, 1071223 (2023).

Wedge, M. E. et al. Virally programmed extracellular vesicles sensitize cancer cells to oncolytic virus and small molecule therapy. Nat. Commun. 13, 1898 (2022).

Petruk, N. et al. CD73 facilitates EMT progression and promotes lung metastases in triple-negative breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 11, 6035 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. MiR-199a-5p suppresses non-small cell lung cancer via targeting MAP3K11. J. Cancer. 10, 2472–2479 (2019).

Ghochikyan, A. et al. Primary 4T1 tumor resection provides critical ‘window of opportunity’ for immunotherapy. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 31, 185–198 (2014).

Huang, Z., Yu, P. & Tang, J. Characterization of Triple-Negative breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 cell spheroid model. Onco Targets Ther. 13, 5395–5405 (2020).

Das, S. et al. Mixed lineage kinase 3 promotes breast tumorigenesis via phosphorylation and activation of p21-activated kinase 1. Oncogene 38, 3569–3584 (2019).

Rattanasinchai, C. & Gallo, K. MLK3 signaling in Cancer invasion. Cancers (Basel). 8, 51 (2016).

Dauer, P. et al. ER stress sensor, glucose regulatory protein 78 (GRP78) regulates redox status in pancreatic cancer thereby maintaining stemness. Cell. Death Dis. 10, 132 (2019).

Lee, A. S. GRP78 induction in cancer: Therapeutic and prognostic implications. Cancer Research vol. 67 3496–3499 Preprint at (2007). https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0325

Bell, J., Parato, K. & Atkins, H. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus. in Viral Therapy of Cancer 187–203 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK, (2008). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470985793.ch11

Luo, Y. et al. Endothelial ETS1 Inhibition exacerbate blood–brain barrier dysfunction in multiple sclerosis through inducing endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell. Death Dis. 13, 462–462 (2022).

Vishnubalaji, R. & Alajez, N. M. Epigenetic regulation of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) by TGF-β signaling. Sci. Rep. 11, 15410 (2021).

Qin, Q., Xu, Y., He, T., Qin, C. & Xu, J. Normal and disease-related biological functions of Twist1 and underlying molecular mechanisms. Cell Research vol. 22 90–106 Preprint at (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2011.144

Plaschka, M. et al. ZEB1 transcription factor promotes immune escape in melanoma. J. Immunother Cancer. 10, e003484 (2022).

Cavallari, I. et al. The miR-200 Family of microRNAs: Fine Tuners of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Circulating Cancer Biomarkers. Cancers (Basel) 13(23), 5874 (2021).

Houssein, E. H. et al. An effective multiclass skin cancer classification approach based on deep convolutional neural network. Cluster Comput. 27, 12799–12819 (2024).

Alzubaidi, L. et al. Novel transfer learning approach for medical imaging with limited labeled data. Cancers (Basel). 13, 1590 (2021).

Kora, P. et al. Transfer learning techniques for medical image analysis: A review. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering vol. 42 79–107 Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbe.2021.11.004

Li, Y., Mansmann, U., Du, S. & Hornung, R. Benchmark study of feature selection strategies for multi-omics data. BMC Bioinform. 23, 412 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Epithelial-type systemic breast carcinoma cells with a restricted mesenchymal transition are a major source of metastasis. Sci. Adv. 5(6), eaav4275 (2019).

Stojdl, D. F. et al. VSV strains with defects in their ability to shutdown innate immunity are potent systemic anti-cancer agents. Cancer Cell. 4, 263–275 (2003).

Alkayyal, A. A. et al. NK-cell recruitment is necessary for eradication of peritoneal carcinomatosis with an IL12-expressing Maraba virus cellular vaccine. Cancer Immunol. Res. 5, 211–221 (2017).

Ye, J. et al. Primer-BLAST: A tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 13, 134 (2012).

Taylor, S. C. et al. The Ultimate qPCR Experiment: Producing Publication Quality, Reproducible Data the First Time. Trends in Biotechnology vol. 37 761–774 Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.12.002

Chen, C. Real-time quantification of MicroRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e179–e179 (2005).

Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the animal facility staff at the Université de Sherbrooke for their assistance with animal wellness.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GSC conceived and designed the study, performed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript; LD and HG designed the study and performed the experiments; RB generated the oncolytic viruses used in this study; CSI conceived and designed the study; LHT conceived and designed the study, wrote the manuscript, supervised and funded the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

St-Cyr, G., Daniel, L., Giguère, H. et al. Therapeutic limitations of oncolytic VSVd51-mediated miR-199a-5p delivery in triple negative breast cancer models. Sci Rep 15, 16634 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01584-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01584-0