Abstract

Anesthesia and perioperative management significantly influence long-term outcomes in patients with early and intermediate stage cancer. Midazolam, a commonly used benzodiazepine anesthetic, has shown potential anti-tumor effects. This study aimed to explore the anti-tumor properties of midazolam in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The anti-tumor effects of midazolam on A549 and H1650 NSCLC cell lines were assessed using CCK-8 assays, colony-forming assays, and the Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate Apoptosis Detection Kit I. Additionally, Transwell assays were conducted in vitro, and subcutaneous tumor models in nude mice were established to assess the anti-tumor effects in vivo. The interaction within the lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis was confirmed through dual-luciferase reporter assays, RT-qPCR, and Western blotting. Midazolam significantly inhibited cell proliferation and invasion while inducing apoptosis in A549 and H1650 cells, both in vitro and in vivo, by promoting autophagy (P<0.05). It also down-regulated the expression of lncRNA XLOC_010706 in the tumor microenvironment (P<0.05). Within the signaling pathway, lncRNA XLOC_010706 functioned as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) targeting miR-520d-5p, with STAT3 identified as a functional target gene for miR-520d-5p in NSCLC. Furthermore, lncRNA XLOC_010706 acted as an oncogene, promoting cell proliferation and invasion while inhibiting apoptosis through the miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis. Midazolam down-regulates the expression of lncRNA XLOC_010706, which acts as an oncogene in NSCLC. The anti-tumor effects of midazolam occur via the lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 pathway, enhancing autophagy in NSCLC. This indicates that lncRNA XLOC_010706 could serve as a novel diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for NSCLC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is one of the most prevalent malignant tumors globally, with a significant increase in both incidence and mortality rates, posing a severe threat to human health1. The role of anesthesia and perioperative management in influencing long-term outcomes for cancer patients has garnered significant attention in recent research2. Midazolam a commonly used sedative and anesthetic inducer for preoperative sedation and nerve block, functions as a gamma- aminobutyric acid (GABA)(A) receptor agonist and is a benzodiazepine derivative3,4. Notably, prior studies have indicated that midazolam anesthesia might possess potential anticancer properties, particularly for hepatocellular carcinoma5 and lung cancer6. Our recent research has further corroborated the anti-tumor effects of midazolam anesthesia in NSCLC7; however, the precise mechanisms underlying these effects remain to be fully elucidated.

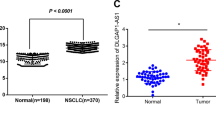

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a novel class of endogenous non-coding RNAs, typically over 200 nucleotides in length, which stably exist in plasma and urine and exhibit disease and tissue specificity without protein-coding potential8,9,10. Of which, lncRNA XLOC_010706, located on chromosome 13: 99487258-99487273, has been previously identified as significantly upregulated in squamous cell lung cancer compared to adjacent normal tissues in a genome-wide expression profiling study, suggesting its potential role in NSCLC tumor biology11.

MiRNAs, a class of short non-coding RNAs ranging from 18-22 nucleotides, play crucial roles as regulatory factors in gene expression at the post-transcriptional level12,13. Extensive studies have shown that miR-520d-5p is involved in a variety of cellular processes and exhibits anti-tumor properties, suppressing tumor metastasis and growth across several cancer types14,15, including cervical cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, glioma, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, and breast cancer16,17,18,19,20,21. The signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling pathway is critical for numerous biological processes, including cellular apoptosis and proliferation, and plays a significant role in the autophagy pathway, which is often activated in various cancers22,23,24. MiR-520d-5p has been identified as a direct target of STAT3 in the context of gastric cancer proliferation. Our previous research also highlighted the involvement of the miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis in the development and progression of NSCLC7.

Based on these findings, we hypothesize that XLOC 010706 may participate in midazolam’s mechanism of action, potentially via interaction with miR-520d-5p. However, there are no reports elucidating whether the anti-tumor effects of midazolam are mediated through the lncRNA XLOC_010706/ miR-520d-5p/STAT3 pathway. Moreover, the role of lncRNA expression in the anti-tumor effects of midazolam remains unclear.

Therefore, the present study aims to thoroughly investigate the anti-tumor effects of midazolam, identify the oncogenic roles of lncRNA XLOC_010706 in NSCLC, and elucidate the relationship between midazolam and the lncRNA XLOC_010706/ miR-520d-5p/STAT3 pathway. By understanding these mechanisms, we hope to shed light on the potential therapeutic applications of midazolam and the molecular interactions involved in its anti-tumor activity. This study could pave the way for novel therapeutic strategies targeting lncRNA XLOC_010706 and its interactions with miR-520d-5p and STAT3 in NSCLC, offering new hope for patients afflicted by this disease.

Materials and methods

Cells

Human NSCLC cell lines A549 and H1650 were obtained from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. A549 and H1650 cells were cultured in high glucose medium at 37˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol® reagent. cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript™ RT-PCR Kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The circRNA, miRNA, and mRNA primer sequences were synthesized by Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. GAPDH expression was used as an internal reference for circRNA and mRNA, while U6 was used as an internal reference for miRNA. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95˚C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94˚C for 15 sec, 55˚C for 30 sec, and 70˚C for 30 sec. After PCR, relative expression levels were calculated using the 2^-ΔΔCq method.

Small interfering (si) RNA transfection

miR-520d-5p mimic and inhibitor, along with controls and siRNAs targeting circRNAs, were designed and synthesized by Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. miR-520d-5p mimic and inhibitor, controls, and siRNAs (50 nM) were transfected into A549 and H1650 cells (1x10^5 cells/well) using Lipofectamine® 3000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 48 h post-transfection, transfection efficiency was verified using RT-qPCR.

MTT assay

At 48 h post-transfection, A549 and H1650 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were digested and seeded into 96-well culture plates at a density of 1x10^5 cells/well. They were then cultured for 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h. MTT solution (20 μL, 2.5 mg/ml) was added to each well to stain the cells for 4 h, followed by the addition of dimethyl sulfoxide (100 μL) to dissolve the crystals. The absorbance value at optical density 450 nm (OD450 nm) was measured using an FL600 microliter plate reader.

Soft agar colony formation assay

Preparation of base Agar and top Agar must be done sterilely using cell culture-grade water. Trypsinize adherent cells to release them and count the number of cells per mL. This procedure requires 5,000 cells/well for a 6-well plate. Adjust the volume so that the cell count is 200,000 cells/ml. Add 0.1 ml of cell suspension to 10 ml tubes. Label 6-well plate base agar dishes appropriately. Add 4 ml of 2X DMEM/F12+2X FCS+2X antibiotics and 4 ml of 0.7% Agar to a tube of cells, mix gently, and add 2 ml to each of the replicate plates. Let the agar solidify at room temperature, then incubate plates at 37˚C in a humidified incubator. Add 0.5 ml media per well the next day and incubate plates for 10 to 30 days, feeding cells 1-2 times per week with cell culture media. Stain plates with 0.5 ml of 0.005% Crystal Violet for more than 1 hour. Count colonies using a dissecting microscope.

EdU staining assay

Using the EdU Proliferation Kit (iFluor 647, ab222421), add EdU solution to A549 and H1650 cells and incubate for 2-4 hrs under optimal growth conditions. Fix cells with fixative solution for 15 min, permeabilize with buffer for 15/20 min, and label EdU with reaction mix for 30 min. Analyze with a flow cytometer or fluorescence microscope.

Matrigel invasion assay

Transfected A549 and H1650 cells (1x10^4 cells/well) in serum-free DMEM were plated in the upper chamber of a Transwell system with 8 µm pores, pre-coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) at 37˚C for 30 min. DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. After 24 h incubation, non-invaded cells were removed, invasive cells were fixed with methanol at 37˚C for 30 min, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet at 37˚C for 30 min. Images of the invasive cells were captured and counted using an IX71 microscope.

Wound healing assay

A549 and H1650 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 2 × 10^5 cells/mL and incubated for 24–48 h. After cells reached 100% confluence, wounds were generated using a 1 mL micropipette tip. Media was removed, cells washed with 500 μL PBS, and 500 μL of complete culture media containing compounds added into each well. Images were acquired immediately following media replacement, and every 6 h for 24 h using a multi-mode plate reader at 10×. Wound areas were measured using ImageJ.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

Target miRNA and target gene were predicted using the lncRNA Interactome and TargetScan databases. The wild-type and mutant sequences of lncRNA and target gene were subcloned into pmirGLO and co-transfected with miRNA mimic and miRNA negative control (NC) into HEK293 cells. Relative luciferase activities were detected using a dual-luciferase reporter assay.

Western blotting

At 48 h post-transfection, A549 and H1650 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were digested, and the culture medium was discarded. Cells were rinsed with PBS three times, and 150 μL of pre-cooled RIPA lysate (containing 1 mmol/L PMSF) was added to extract the total protein. The lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 r/min at 4°C for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was measured using the BCA method, and proteins were denatured at 99°C for 10 minutes. 50 μg protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and incubated in blocking solution for 1 hour. The membrane was then incubated with primary antibodies (1:100) and β-actin (1:1,000) at 4°C overnight. After washing with TBST, the membrane was incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibodies (1:5000) at 37°C for 2 hours.

In vivo animal assay

To validate the anti-tumor effect of midazolam and lncRNA XLOC_010706 on NSCLC cells, subcutaneous tumor models in nude mice were established via A549 cell injection. BALB/c nude mice (male, 6-8 weeks old), purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd., were maintained in an AAALAC-accredited specific pathogen-free facility under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Experimental groups included: 1) blank control, 2) cisplatin positive control, 3) midazolam treatment, 4) lncRNA overexpression, and 5) lncRNA overexpression + midazolam. Tumor volumes were measured weekly using the formula V=1/2×Width^2×Length. After 5 weeks, each mouse was anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 0.25% tribromoethanol (Sigma Co., Ltd.) at a dose of 0.2 ml/10g body weight. Following anesthesia, the mice were euthanized via cardiac exsanguination to ensure complete and humane sacrifice. Furthermore, subcutaneous tumors were removed, measured, weighed, and analyzed for histological changes, Ki-67 staining, TUNEL assay, and lncRNA-XLOC010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 expression. All experimental procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Central Hospital of Shenyang Medical College (SMCCHM 20230021), following ARRIVE guidelines and the Basel declaration.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 18.0 software. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three repeats. Cell line data and lncRNA expression were compared using an unpaired Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Midazolam can inhibit cell proliferation

We treated A549 and H1650 cells with different concentrations of midazolam (0 µg/mL, 20 µg/mL, 40 µg/mL, 60 µg/mL, 80 µg/mL) and cisplatin (0 µg/mL, 2 µg/mL, 4 µg/mL, 6 µg/mL, 8 µg/mL). MTT assay results showed that midazolam had an inhibitory effect on the proliferation of A549 and H1650 cells, exhibiting dose-dependent behavior, with IC50 values of 25.80 µg/mL and 27.69 µg/mL, respectively. Cisplatin, used as a positive control, showed significant proliferation inhibition on A549 and H1650 cells, with IC50 values of 1.131 µg/mL and 1.204 µg/mL. The combination of midazolam and cisplatin had a significant synergistic effect, reducing the IC50 values of cisplatin to 0.706 µg/mL and 0.746 µg/mL, respectively (P<0.05; Fig. 1A). We treated A549 and H1650 cells with 20 µg/mL of midazolam and/or 2 µg/mL of cisplatin for 48 hours. Compared with the PBS group, soft agar colony formation and EdU+ staining assays showed that midazolam could partially inhibit A549 and H1650 cell clone formation (P<0.05; Fig. 1B) and DNA replication activity (P<0.05; Fig. 2A). The combination of midazolam and cisplatin exhibited a significant synergistic effect.

Midazolam can inhibit cell proliferation and clone. We treated A549 and H1650 cells with different concentrations of midazolam and cisplatin (The concentration of midazolam used was 20 µg/mL). (A) MTT assay showed that midazolam significantly inhibited cell proliferation of A549 and H1650 cells. (B) Colony formation assays indicated that midazolam significantly inhibited cell clone of A549 and H1650 cells. And the combination of midazolam and cisplatin has a significant synergistic effect. n=3, *P<0.05.

Midazolam can inhibit DNA replication activity and cell invasion. We treated A549 and H1650 cells with 20 µg/mL of midazolam and/or 2 µg/mL of cisplatin for 48 hours. (A) EdU+ Staining assay showed that midazolam significantly inhibited DNA replication activity of A549 and H1650 cells. (B) Matrigel invasion assay significantly indicated that midazolam inhibited cell invasion of A549 and H1650 cells. And the combination of midazolam and cisplatin has a significant synergistic effect. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Midazolam can inhibit cell invasion and migration

We treated A549 and H1650 cells with 20 µg/mL of midazolam and/or 2 µg/mL of cisplatin for 48 hours. Compared with the PBS group, matrigel invasion and wound healing assays showed that midazolam could partially inhibit A549 and H1650 cell invasion (P<0.05; Fig. 2B) and migration (P<0.05; Fig. 3A). The combination of midazolam and cisplatin had a significantly synergistic effect.

Midazolam can inhibit cell migration and promote cell apoptosis. We treated A549 and H1650 cells with 20 µg/mL of midazolam and/or 2 µg/mL of cisplatin for 48 hours. (A) Wound healing assay showed that midazolam significantly inhibited cell migration of A549 and H1650 cells. (B) Annexin V-FITC/PI assay indicated that midazolam promoted cell apoptosis of A549 and H1650 cells. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Midazolam can promote cell apoptosis

We treated A549 and H1650 cells with 20 µg/mL of midazolam and/or 2 µg/mL of cisplatin for 48 hours. Compared with the PBS group, Annexin V-FITC/PI assay showed that midazolam could partially promote A549 and H1650 cell apoptosis (P<0.05; Figure 3B). The combination of midazolam and cisplatin had a significantly synergistic effect.

Midazolam intervention on lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis and cell autophagy

RT-qPCR assay results showed that after treating A549 and H1650 cells with 20 µg/mL of midazolam for 48 hours, lncRNA-XLOC_010706 expression significantly decreased (P<0.05; Fig. 4A), miR-520d-5p expression significantly increased (P<0.05; Fig. 4B), and STAT3 mRNA (P<0.05; Fig. 4C) and STAT3 protein (P<0.05; Fig. 4D) expression significantly decreased. Additionally, after treatment with midazolam, Atg5, Beclin 1, LC3B, and ULK1 protein expression significantly increased in A549 and H1650 cells (P<0.05; Fig. 4E), promoting cell autophagy.

Midazolam inhibited lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis and promoted cell autophagy. After treated A549 and H1650 cells with 20 µg/mL of midazolam for 48 hours, RT-qPCR assay results showed that lncRNA-XLOC_010706 expression significantly decreased (A), miR-520d-5p expression significantly increased (B), and STAT3 mRNA (C) and STAT3 protein (D) expression significantly decreased, and, Atg5, Beclin 1, LC3B, ULK1 protein expression significantly increased (E) in A549 and H1650 cells. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Successful cell transfection

We transfected plasmids overexpressing lncRNA XLOC_010706 (lncRNA OV) and blank plasmids (OV-NC) into A549 and H1650 cells to upregulate lncRNA XLOC_010706 expression. We also transfected shRNAs targeting lncRNA XLOC_010706 (sh-lncRNA) and the corresponding negative control (sh-NC) to silence lncRNA XLOC_010706 expression. Transfection efficiency was verified by a confocal laser scanning microscope (Figure 5A) and RT-qPCR assay (P<0.05; Figure 5A).

lncRNA-XLOC_010706 promoted cell proliferation and clone. (A) A549 and H1650 cells that were transfected with lnRNA OV and shRNA, respectively, were subjected to confocal laser scanning microscope and RT-qPCR assay for lncRNA-XLOC_010706 expression. n=3, *P<0.05. (B) MTT and (C) Colony formation assay showed that lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpressing significantly promoted cell proliferation and clone, and lncRNA-XLOC_010706 silence inhibited cell proliferation and clone of A549 and H1650 cells. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

lncRNA-XLOC_010706 can promote cell proliferation, invasion, and migration and inhibit cell apoptosis

Following transfection with lncRNA OV and sh-lncRNA, the potential functions of lncRNA-XLOC_010706 on cell proliferation, invasion, and migration were analyzed. The results showed that cell viability, colony formation, DNA replication, and cell invasion and migration activities were significantly increased in the lncRNA OV group and significantly decreased in the sh-lncRNA group compared with the corresponding NC groups (P<0.05; Figs. 5B,C, 6A,B, 7A). Conversely, the apoptosis rate was markedly decreased in the lncRNA OV group and significantly increased in the sh-lncRNA group compared with the corresponding NC groups (P<0.05; Fig. 7B). These results suggest that lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpression promotes cell proliferation, invasion, and migration and inhibits apoptosis, whereas lncRNA-XLOC_010706 silencing inhibits cell proliferation, invasion, and migration and promotes apoptosis, acting as an oncogene in NSCLC.

lncRNA-XLOC_010706 promoted DNA replication activity and cell invasion. (A) EdU+ Staining and (B) Matrigel invasion assay indicated that lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpressing significantly promoted DNA replication activity and cell invasion, and lncRNA-XLOC_010706 silence inhibited DNA replication activity and cell invasion of A549 and H1650 cells. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

lncRNA-XLOC_010706 promoted cell migration and inhibited cell apoptosis. (A) Wound healing assay and (B) Annexin V-FITC/PI assay indicated that lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpressing significantly promoted cell migration and inhibited cell apoptosis, and lncRNA-XLOC_010706 silence inhibited cell migration and promoted cell apoptosis of A549 and H1650 cells. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

lncRNA XLOC_010706 serves as a ceRNA for miR-520d-5p

It is well known that lncRNAs can act as miRNA sponges to regulate target gene expression. In our study, miR-520d-5p was predicted as the highest targeted miRNA for lncRNA XLOC_010706. Arraystar’s proprietary software demonstrated that miR-520d-5p could specifically bind to lncRNA XLOC_010706 (Fig. 8A). Dual-luciferase reporter assay confirmed that miR-520d-5p competitively targeted lncRNA XLOC_010706 (P<0.05; Fig. 8C). In addition, RT-qPCR assay demonstrated that miR-520d-5p expression was significantly decreased in the lncRNA OV group and increased in the sh-lncRNA group compared with the NC groups (P<0.05; Fig. 8B). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) found that lncRNA XLOC_010706 and miR-520d-5p were located in the cytoplasm and nucleus, respectively (Fig. 8D). Therefore, these results demonstrate that lncRNA XLOC_010706 serves as a ceRNA for miR-520d-5p. Our previous study showed that STAT3 is a functional target gene for miR-520d-5p. The lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis is considered a key regulatory axis for the occurrence and development of NSCLC.

lncRNA-XLOC_010706 serves as a ceRNA for miR-520d-5p. (A) The potential binding site of lncRNA-XLOC_010706 to miR-520d-5p. (B) RT-qPCR assay demonstrated that miR-520d-5p expression was significantly decreased in lnRNA OV group and increased in sh-lncRNA group compared with that in the OV-NC and sh-NC group. (C) Dual-luciferase reporter assay confirmed that miR-520d-5p could competitively targeted lncRNA XLOC_010706 (HEK-293T). n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, na P>0.05. (D) Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) found that lncRNA XLOC_010706 and miR-520d-5p were located in the cytoplasm and nucleus respectively.

Rescue assays

Rescue assays were performed to assess the relationship between lncRNA XLOC_010706, miR-520d-5p, and STAT3. The effects of lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p on STAT3 expression and cell proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis were analyzed. Western blot assay revealed that STAT3 protein expression was significantly increased in the lncRNA OV group and significantly decreased in the sh-lncRNA group; however, these effects were attenuated by miR-520d-5p mimic and inhibitor, respectively (P<0.05; Fig. 9A). Furthermore, MTT, Matrigel invasion, and Annexin V-FITC/PI assay results showed that lncRNA XLOC_010706 overexpression promoted cell proliferation and invasion and inhibited cell apoptosis, while lncRNA XLOC_010706 silencing inhibited cell proliferation and invasion and promoted cell apoptosis. This effect was reversed following miR-520d-5p mimic and mimic inhibitor treatment (P<0.05; Figs. 9C, 10A, B).

Rescue assays. A549 cells were co-transfected with the lncRNA XLOC_010706 OV vector and miR-520d-5p mimics. H1650 cells were also co-transfected with sh-lncRNA XLOC_010706 and miR-520d-5p inhibitors. Western-blot assay analysis of STAT3 protein expression (A) and (B) Atg5, Beclin 1, LC3B, ULK1 protein expression in lncRNA XLOC_010706 and miR-520d-5p transfection groups. (C) MTT assay showed the effects of lncRNA XLOC_010706/ miR-520d-5p axis on cell proliferation. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Rescue assays. A549 cells were co-transfected with the lncRNA XLOC_010706 OV vector and miR-520d-5p mimics. H1650 cells were also co-transfected with sh-lncRNA XLOC_010706 and miR-520d-5p inhibitors. (A) Matrigel invasion and (B) Annexin V-FITC/PI assay showed the effects of lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p axis on cell invasion and apoptosis. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis with cell autophagy

Previous assays found that midazolam can promote cell autophagy and affect lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis expression in NSCLC. Our study also observed the effect of the lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3-axis on cell autophagy. RT-qPCR assay results showed that Atg5, Beclin 1, LC3B, and ULK1 protein expression significantly decreased in the lncRNA OV groups and increased in the sh-lncRNA groups. These results indicate that lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpression inhibited autophagy, while lncRNA-XLOC_010706 silencing promoted cell autophagy. This effect was reversed following miR-520d-5p mimic and mimic inhibitor treatment (P<0.05; Fig. 9B). This suggests that the lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis has a cooperative effect on cell autophagy, with midazolam promoting cell autophagy via the lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis in NSCLC.

Midazolam suppresses the progression of NSCLC in vivo

To further study the roles of midazolam and lncRNA-XLOC_010706 in vivo, we established subcutaneous tumor models in nude mice, using PBS as the control group and cisplatin as the positive control group (Fig. 11A). Compared with the PBS group, the tumor growth rate, tumor weight, and volume were significantly reduced in the midazolam-treated group and increased in the lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpressing group (P<0.05; Fig. 11B,C). Ki-67 staining was performed to detect the proliferative index of A549 cells in vivo. The percentage of Ki-67 positive cancer cells was notably reduced in the midazolam group and increased in the lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpressing group compared to the PBS group. However, this effect was reversed following midazolam treatment, with the proportion of Ki-67 being the lowest in the cisplatin positive control group (P<0.05; Fig. 11D). Additionally, TUNEL apoptosis assay with xenograft tumor samples revealed that midazolam facilitated the apoptosis of A549 cells in vivo, while lncRNA-XLOC_010706 inhibited cell apoptosis. This effect was also reversed following midazolam treatment, with the proportion of apoptosis being the highest in the cisplatin positive control group (P<0.05; Fig. 12A,B). These results suggest a potential inhibitory effect of midazolam on the progression of A549 cells in vivo by regulating proliferation and apoptosis.

Midazolam suppresses tumor growth of NSCLC in vivo. (A) We established subcutaneous tumor models in nude mice via A549 cells subcutaneous injection. After 5 weeks of feeding, the mice were euthanized, and nude mice were taken out to measure their size and weighed. (B) Tumor growth curves and (C) tumor weight revealed that midazolam significantly reduced and lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpressing promoted A549 cell growth in vivo. n=5, *P<0.05. (D) The percentage of Ki-67 positive cancer cells in midazolam group was notably reduced and compare in midazolam group and increased in lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpressing group. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Midazolam inhibits cell apoptosis and lncRNA-XLOC_010706/ miR-520d-5p/STAT3 expression in vivo. (A,B) TUNEL apoptosis assay with xenograft tumor samples revealed that midazolam facilitated the apoptosis and lncRNA-XLOC_010706 inhibited cell apoptosis of A549 cells in vivo. RT-qPCR and western-blot assay results showed that lncRNA-XLOC_010706 expression significantly decreased (C), miR-520d-5p expression significantly increased (D), and STAT3 mRNA (E) and protein (F) expression significantly decreased in midazolam group. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Midazolam inhibits lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 expression in vivo

More importantly, RT-qPCR and western blot assay results showed that lncRNA-XLOC_010706 expression significantly decreased (P<0.05; Fig. 12C), miR-520d-5p expression significantly increased (P<0.05; Fig. 12D), and STAT3 mRNA (P<0.05; Fig. 12E) and protein (P<0.05; Fig. 12F) expression significantly decreased in the midazolam group. These results indicate that midazolam can inhibit lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis expression in vivo. Conversely, lncRNA-XLOC_010706 expression significantly increased (P<0.05; Fig. 12C), miR-520d-5p expression significantly decreased (P<0.05; Fig. 12D), and STAT3 mRNA (P<0.05; Fig. 12E) and protein (P<0.05; Fig. 12F) expression significantly increased in the lncRNA-XLOC_010706 overexpressing group; however, this effect was reversed following midazolam treatment. These results indicate that midazolam can inhibit lncRNA-XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis expression in vivo.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the oncogenic role of lncRNA XLOC_010706 in NSCLC and the first to report the involvement of midazolam in regulating the lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 pathway. Midazolam, a sedative and anesthetic inducer extensively used for preoperative sedation and nerve block, is a GABA(A) receptor agonist and a derivative of benzodiazepine25. Besides its well-known sedative effects, midazolam and other anesthetic agents have demonstrated neuronal cytotoxicity and apoptosis-inducing activity in various cell types, including hematogenic, ectodermal, mesenchymal, and neuronal cells26. For instance, midazolam has been reported to induce apoptosis in K562 and HT29 cells and inhibit tumor growth in xenotransplantation models, potentially through the suppression of ROS production, thereby modulating apoptosis and growth regulatory proteins. Furthermore, Apostolia-Maria Tsimberidou et al.27 have documented that midazolam enhances the antitumor activity of pharmacokinetics in patients with ovarian and pancreatic cancers. Additionally, Qian Shen et al.5 demonstrated that midazolam significantly suppressed the viability, invasiveness, and migration of Hep3B and SK-HEP-1 cells, alongside an increase in miR-217 levels in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells, which inhibited metastasis and promoted apoptosis. Our previous research7 also indicated that midazolam induces apoptosis in A549 cells and modulates the expression of apoptosis-related proteins Bcl-2, Bax, and Caspase-3, thereby exerting anti-tumor effects in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Given these findings, we comprehensively provided the potential therapeutic applications of midazolam and the molecular interactions involved in its anti-tumor activity. This study could pave the way for novel therapeutic strategies targeting lncRNA XLOC_010706 and its interactions with miR-520d-5p and STAT3 in NSCLC, offering new hope for patients suffering from this disease.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a novel class of endogenous non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) comprising RNA molecules longer than 200 nucleotides. These molecules stably exist in plasma and urine, exhibiting disease and tissue specificity without protein-coding potential. lncRNAs have been implicated in a variety of diseases, including cancer, diabetes mellitus, neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and autoimmune diseases28,29. Recent studies have highlighted the abnormal expression of lncRNAs in tumor tissues, linking it closely to the occurrence, development, and prognosis of NSCLC30,31. lncRNA XLOC_010706, located on chromosome 13 (chr13: 99487258-99487273), has been identified as an oncogene in NSCLC, promoting cell proliferation and invasion while inhibiting apoptosis. Our current study is the first to report its oncogenic role in NSCLC. Additionally, we discovered that midazolam down-regulates lncRNA XLOC_010706 expression in the tumor microenvironment, suggesting a potential anti-tumor mechanism of midazolam.

lncRNAs may function as microRNA (miRNA/miR) sponges, competitively binding to miRNA response elements and influencing downstream target gene expression. This post-translational regulation affects gene function and contributes to various biological processes32. miRNAs, a class of non-coding short RNAs (18-22 nucleotides), are crucial regulatory factors for gene expression at the post- transcriptional level33. In our study, dual-luciferase reporter assays, RT-qPCR, and Western blot assays identified that lncRNA XLOC_010706 acts as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) targeting miR-520d-5p. Previous studies have shown that miR-520d-5p suppresses tumor metastasis and growth in various cancers16,17,18,19,20,21. Our earlier research reported downregulation of miR-520d-5p in NSCLC, with current results suggesting its regulation by lncRNA XLOC_010706. The STAT3 signaling pathway, linked to numerous biological processes such as cellular apoptosis and proliferation, has been identified as a direct target of miR-520d-5p in NSCLC. Consequently, lncRNA XLOC_010706 promotes cell proliferation and invasion, and inhibits apoptosis via the miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis in NSCLC.

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved intracellular catabolic process, where cytoplasmic macromolecules and aggregated proteins are delivered to lysosomes, digested by lysosomal hydrolases, and recycled into the cytosol34,35,36,37. Depending on the context, autophagy can have opposing roles in cancer, with both stimulation and inhibition proposed as therapeutic strategies38,39,40. STAT3 signaling plays a significant role in autophagy regulation, influencing it through transcriptional and non- transcriptional mechanisms based on its subcellular localization41. Cytoplasmic STAT3 inhibits autophagy by increasing the expression of negative regulatory factors such as BCL2, BCL2L1, and MCL1, and by interacting with eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 2 (EIF2AK2) and forkhead box O (FOXO)42,43. Conversely, nuclear STAT3 regulates HIF-1α and BNIP3 to promote autophagy24,44. Our findings indicate that STAT3 inhibits autophagy in NSCLC progression, whereas midazolam promotes autophagy in NSCLC cells. Thus, we infer that midazolam exerts anti-tumor effects through the lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 pathway by promoting autophagy in NSCLC.

Furthermore, the mechanism by which midazolam increases cisplatin sensitivity in NSCLC remains unclear. Limited literature exists on midazolam’s role in regulating chemoresistance, particularly concerning cisplatin sensitivity in NSCLC. Tingting Sun et al6 reported that midazolam anesthesia reduced cisplatin resistance in cisplatin- resistant NSCLC (CR-NSCLC) cells by regulating the miR-194-5p/hook microtubule- tethering protein 3 (HOOK3) axes. Our study corroborates this finding, suggesting that midazolam enhances cisplatin sensitivity in NSCLC. This implies that midazolam could be used as an adjunctive therapy to overcome cisplatin resistance in clinical practice, though further investigation is needed to confirm its clinical efficacy.

While this study provides valuable insights into the anti-tumor effects of midazolam on NSCLC through the lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 pathway, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the experiments were primarily conducted using A549 and H1650 cell lines and subcutaneous cancer models in nude mice, which may not fully replicate the complexity of NSCLC in human patients. Therefore, further validation in clinical settings is necessary to confirm these findings. Second, the study focuses on a specific signaling pathway, and other potential mechanisms by which midazolam exerts its anti-tumor effects were not explored. Third, although lncRNA XLOC 010706 has been previously identified as significantly upregulated in squamous cell lung cancer through genome-wide expression profiling11, its direct association with midazolam treatment had not been previously established. Our earlier findings demonstrated that miR-520d-5p mediates the antitumor effects of midazolam in NSCLC7, leading us to hypothesize a potential regulatory axis involving XLOC 010706. This hypothesis was preliminarily supported by the current study; however, further transcriptomic analyses in midazolam-treated NSCLC cells are still needed to validate this association and elucidate its underlying molecular mechanism. Lastly, the long-term effects and safety of midazolam usage in cancer patients were not assessed in this study, highlighting the need for more comprehensive investigations before translating these findings into clinical practice.

Conclusion

This study determined that midazolam within the tumor microenvironment can down-regulate lncRNA XLOC_010706 expression. lncRNA XLOC_010706 functions as an oncogene, promoting cell proliferation and invasion while inhibiting apoptosis via the miR-520d-5p/STAT3 axis in NSCLC. Midazolam exerts its anti-tumor effects by modulating the lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3 pathway and promoting autophagy in NSCLC. Therefore, lncRNA XLOC_010706 may serve as a novel diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for patients with NSCLC.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further details are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- CR-NSCLC:

-

Cisplatin-resistant NSCLC

- EIF2AK2:

-

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 2

- FOXO:

-

Forkhead box O

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HOOK3:

-

Hook microtubule-tethering protein 3

- lncRNAs:

-

Long noncoding RNAs

- NC:

-

Negative control

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- STAT3:

-

Signal transducer and activator of the transcription 3

- RT-qPCR:

-

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

- WB:

-

Western-blot

References

Herbst, R. S., Morgensztern, D. & Boshoff, C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 553(7689), 446–454 (2018).

Dubowitz, J. A., Sloan, E. K. & Riedel, B. J. Implicating anaesthesia and the perioperative period in cancer recurrence and metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 35(4), 347–358 (2018).

Zarour, S. et al. The association between midazolam premedication and postoperative delirium—A retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Anesth. 92, 111113 (2023).

Barends, C. et al. Development of a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model for intranasal administration of midazolam in older adults: A single-site two-period crossover study. Br. J. Anaesth. S0007–0912(23), 00228–3 (2023).

Shen, Q., Xia, Y., Yang, L., Wang, B. & Peng, J. Midazolam suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma cell metastasis and enhances apoptosis by elevating miR-217. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2813521 (2022).

Sun, T., Chen, J., Sun, X. & Wang, G. Midazolam increases cisplatin-sensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) via the miR-194-5p/HOOK3 axis. Cancer Cell Int. 21(1), 401 (2021).

Jiao, J., Wang, Y., Sun, X. & Jiang, X. Midazolam induces A549 cell apoptosis in vitro via the miR-520d-5p/STAT3 pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 11(3), 1365–1373 (2018).

Taheri, M., Askari, A., Hussen, B. M., Eghbali, A. & Ghafouri-Fard, S. A review on the role of MYC-induced long non-coding RNA in human disorders. Pathol. Res. Pract. 248, 154568 (2023).

Bhattacharjee, R. et al. Crosstalk between long noncoding RNA and microRNA in Cancer. Cell Oncol. (Dordr.) https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-023-00806-9 (2023).

Asemi, R. et al. Modulation of long non-coding RNAs by resveratrol as a potential therapeutic approach in cancer: A comprehensive review. Pathol. Res. Pract. 246, 154507 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Genome-scale long noncoding RNA expression pattern in squamous cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 5, 11671 (2015).

Thomaidou, A. C. et al. miRNA-guided regulation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from the umbilical cord: Paving the way for stem-cell based regeneration and therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(11), 9189 (2023).

Smolarz, B., Durczyński, A., Romanowicz, H., Szyłło, K. & Hogendorf, P. miRNAs in cancer (review of literature). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(5), 2805 (2022).

Lu, J. et al. MiR-520d-5p modulates chondrogenesis and chondrocyte metabolism through targeting HDAC1. Aging (Albany NY) 12(18), 18545–18560 (2020).

Deshpande, R. P., Chandra Sekhar, Y. B. V. K., Panigrahi, M. & Babu, P. P. SIRP alpha protein downregulates in human astrocytoma: Presumptive involvement of Hsa-miR-520d-5p and Hsa-miR-520d-3p. Mol. Neurobiol. 54(10), 8162–8169 (2017).

Zhang, L., Liu, F., Fu, Y., Chen, X. & Zhang, D. MiR-520d-5p functions as a tumor-suppressor gene in cervical cancer through targeting PTK2. Life Sci. 254, 117558 (2020).

Miura, N., Ishihara, Y., Miura, Y., Kimoto, M. & Miura, K. miR-520d-5p can reduce the mutations in hepatoma cancer cells and iPSCs-derivatives. BMC Cancer 19(1), 587 (2019).

Zhi, T. et al. MicroRNA-520d-5p inhibits human glioma cell proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest by directly targeting PTTG1. Am. J. Transl. Res. 9(11), 4872–4887 (2017).

Yan, L. et al. SP1-mediated microRNA-520d-5p suppresses tumor growth and metastasis in colorectal cancer by targeting CTHRC1. Am. J. Cancer Res. 5(4), 1447–1459 (2015).

Li, T. et al. Gastric cancer cell proliferation and survival is enabled by a cyclophilin B/STAT3/miR-520d-5p signaling feedback loop. Cancer Res. 77(5), 1227–1240 (2017).

Liu, B. et al. MYBL2-induced PITPNA-AS1 upregulates SIK2 to exert oncogenic function in triple-negative breast cancer through miR-520d-5p and DDX54. J. Transl. Med. 19(1), 333 (2021).

Hillmer, E. J., Zhang, H., Li, H. S. & Watowich, S. S. STAT3 signaling in immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 31, 1–15 (2016).

Al-Hetty, H. R. A. K. et al. STAT3 signaling in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A candidate therapeutic target. Pathol. Res. Pract. 245, 154425 (2023).

You, L. et al. The role of STAT3 in autophagy. Autophagy 11(5), 729–739 (2015).

Elshater AA, Sadek AA, Abdelkreem E. Levetiracetam and Midazolam vs Midazolam Alone for First-Line Treatment of Children With Generalized Convulsive Status Epilepticus (Lev-Mid Study): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Indian Pediatr. S097475591600514 (2023).

Mishra, S. K. et al. Midazolam induces cellular apoptosis in human cancer cells and inhibits tumor growth in xenograft mice. Mol. Cells 36(3), 219–226 (2013).

Tsimberidou, A. M. et al. Pharmacokinetics and antitumor activity of patupilone combined with midazolam or omeprazole in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 68(6), 1507–1516 (2011).

Safi, A. et al. The role of noncoding RNAs in metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 28(1), 37 (2023).

Maroni, P., Gomarasca, M. & Lombardi, G. Long non-coding RNAs in bone metastasis: progresses and perspectives as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 14, 1156494 (2023).

Sun, J. et al. Identification of tumor immune infiltration-associated lncRNAs for improving prognosis and immunotherapy response of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 8(1), e000110 (2020).

Rajakumar, S. et al. Long non-coding RNAs: an overview on miRNA sponging and its co-regulation in lung cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50(2), 1727–1741 (2023).

Esposito, R. et al. Tumour mutations in long noncoding RNAs enhance cell fitness. Nat. Commun. 14(1), 3342 (2023).

He, B. et al. miRNA-based biomarkers, therapies, and resistance in Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16(14), 2628–2647 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Autophagy-driven regulation of cisplatin response in human cancers: Exploring molecular and cell death dynamics. Cancer Lett. 587, 216659 (2024).

Lu, Q. et al. Nanoparticles in tumor microenvironment remodeling and cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 17, 16 (2024).

Rizzo, A. et al. Hypertransaminasemia in cancer patients receiving immunotherapy and immune-based combinations: The MOUSEION-05 study. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 72, 1381–1394 (2023).

Guven, D. C. et al. The association between albumin levels and survival in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 1039121 (2022).

Dall’Olio, F. G. et al. Immortal time bias in the association between toxicity and response for immune checkpoint inhibitors: A meta-analysis. Immunotherapy 13, 257–270 (2021).

Rizzo, A. Identifying optimal first-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma with high PD-L1 expression: A matter of debate. Br. J. Cancer 127, 1381–1382 (2022).

Xue, W. et al. Wnt/β-catenin-driven EMT regulation in human cancers. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 81, 79 (2024).

Sadrkhanloo, M. et al. STAT3 signaling in prostate cancer progression and therapy resistance: An oncogenic pathway with diverse functions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 158, 114168 (2023).

Ruan, J. et al. Colorectal cancer inhibitory properties of polysaccharides and their molecular mechanisms: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 238, 124165 (2023).

Ahmad, B. et al. Natural polyphyllins (I, II, D, VI, VII) reverses cancer through apoptosis, autophagy, mitophagy, inflammation, and necroptosis. Onco Targets Ther. 14, 1821–1841 (2021).

Laribee, R. N., Boucher, A. B., Madireddy, S. & Pfeffer, L. M. The STAT3-regulated autophagy pathway in glioblastoma. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 16(5), 671 (2023).

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82003882), LiaoNing Revitalization Talents Program (XLYC2203192), and Guangzhou Science and Technology Project - Joint Funding Program between the City, Universities (Institutes), and Enterprises (SL2024A03J01130). The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JHJ conceived and designed the study. JHJ, YFT, and ZHY performed experiment. JHJ, LY, YRY, and ZHL analyzed and interpreted the data. JHJ and YFT drafted the manuscript. JHJ, YFT, and ZHL critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the animal ethics committee of Central Hospital of Shenyang Medical College. Animal care and experiments were conducted in compliance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and NIH guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiao, J., Tang, Y., Ye, L. et al. Unraveling the anti-tumor effects of midazolam in non-small cell lung cancer through the lncRNA XLOC_010706/miR-520d-5p/STAT3/autophagy pathway. Sci Rep 15, 16796 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01625-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01625-8