Abstract

Kidney tumors are hypervascular tumors with crucial antiangiogenic effects in tumor therapy. This study aimed to develop a predictive model for kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) by utilizing angiogenesis-related genes to formulate targeted therapy and immunotherapy strategies. Angiogenesis-related genes were screened via the GeneCard and Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). The KIRC data downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were randomly divided into an experimental cohort and a validation cohort. In the experimental cohort, a risk score prediction model was constructed through successive analyses via univariate Cox regression, LASSO regression, and multivariate Cox regression. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were employed to assess the sensitivity of the model’s predictions. The model’s stability and generalizability were subsequently validated in both the validation cohort and the E-MTAB-1980 cohort. Subsequently, the TCGA-KIRC dataset was stratified into two distinct groups: a localized tumor cohort and a progression/metastasis cohort, based on tumor staging criteria. The efficacy of the prognostic prediction model was evaluated within each subgroup. A nomogram model was developed in conjunction with each independent prognostic factor to accurately predict patient outcomes. Additionally, single-cell and intercellular communication analyses were conducted via KIRC single-cell data obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. The effects of immunotherapy and targeted therapy on patients were predicted via prognostic modeling. A total of 260 angiogenesis-related genes were identified through screening in the GeneCards and Molecular Signatures Database(MSigDB). We subsequently developed a risk model comprising five genes: MEOX2, PLG, PROX1, TEK, and TIMP1. Survival analysis indicated that the prognosis for high-risk patients was significantly poorer than that for low-risk patients (P < 0.001), and the model demonstrated satisfactory accuracy in predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates. This finding was further validated in both internal and external validation cohorts. The model demonstrated applicability for prognostic predictions in both the localized tumor cohort and the progression/metastasis cohort, with proficiency in forecasting the prognosis of patients diagnosed with metastatic renal cancer. The AUC values for 1, 3, and 5 years were recorded at 0.691, 0.709, and 0.773, respectively. We successfully constructed a nomogram model to facilitate accurate prognostic predictions for patients. Analysis of single-cell data revealed that PLG was expressed predominantly in tumor cell clusters, whereas TEK was highly expressed primarily in pericytes. TIMP1 was found to be highly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells. In contrast, MEOX2 and PROX1 were highly expressed in specific cell clusters but presented low expression levels across the overall cell population. Cell communication analysis indicated that the modeling gene TEK was involved in the angiogenic pathway, with the interaction between the ligand ANGPT2 and the receptor ITGA5-ITGB1 being particularly prominent in this study. Furthermore, the immune dysfunction and rejection scores for high-risk patients within the non-localized renal cancer cohort were markedly elevated compared to those observed in the low-risk group. In terms of targeted pharmacological intervention, individuals classified in the low-risk group exhibited a heightened sensitivity to sorafenib. The KIRC prognostic prediction model, which is based on five angiogenesis-related genes, demonstrated reliable performance, indicating that high-risk patients have a significantly poorer prognosis than low-risk patients do. The developed nomogram model effectively visualizes and accurately predicts patient prognosis. It is essential to highlight that individuals diagnosed with low-risk metastatic KIRC may experience greater advantages from the administration of immunotherapy and sorafenib.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC), which arises from renal tubular epithelial cells, is the malignant neoplasm with the highest morbidity and mortality rates in the field of urology1. Among its subtypes, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) is the predominant form, accounting for approximately 75 to 80% of all renal cancer cases2. Surgical intervention can yield favorable outcomes for patients diagnosed with early-stage renal cancer3; however, approximately 25% of patients with localized renal cancer experience recurrent metastasis following surgical treatment4. Extensive clinical evidence indicates that metastatic KIRC is insensitive to both local radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy, resulting in a 5-year survival rate of only 11.7%4. Consequently, accurately predicting patient prognosis and selecting appropriate therapeutic agents for those with metastatic disease remain significant challenges.

Angiogenesis is defined as the process of forming new blood vessels through the proliferation, differentiation, and migration of endothelial cells, which can occur in both budding and nonbudding forms, originating from preexisting capillaries or microvessels5. This process can manifest in both physiological and pathological contexts. Physiological angiogenesis plays a crucial role in human growth and development, as well as in the healing of traumatic injuries. Conversely, pathological angiogenesis may arise in conditions such as diabetic microangiopathy, rheumatoid arthritis, and other nonneoplastic diseases, in addition to neoplastic diseases6. Current research indicates a significant association between angiogenesis and both solid and hematologic tumors. The hypoxic microenvironment that characterizes tumors, along with certain cytokines secreted by tumor tissues, can act as stimulants for tumor angiogenesis, thereby facilitating cancer metastasis and invasion7.

KIRC is widely recognized as a highly vascularized solid tumor8, prompting the development of numerous pharmacological agents aimed at targeting tumor angiogenesis. Among the various proangiogenic factors activated by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stands out as a potent mitogen for endothelial cells and is significantly overexpressed in a range of tumors9. Consequently, researchers have identified VEGF as a therapeutic target, leading to the development of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as sorafenib, pazopanib, axitinib, and sunitinib. Additionally, the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) plays a critical role in regulating cellular processes, including differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis. mTOR inhibitors, such as everolimus and tesirolimus, have been developed to target this pathway10. Currently, these two classes of drugs are extensively utilized in clinical settings as first- or second-line treatments for patients with advanced renal cancer, providing significant benefits to many individuals. Nevertheless, the challenge of personalizing treatment regimens for patients remains an unresolved issue.

In this study, we constructed a prognostic prediction model for KIRC based on angiogenesis-related genes (ARGs) via bioinformatics methodologies. This model was further employed to predict the efficacy of immunotherapy and targeted therapy in patients to facilitate individualized treatment recommendations.

Methods

Data acquisition and processing

ARGs were identified through a screening process conducted in the PathCards section of the GeneCard database, utilizing the search term “Angiogenesis”. This process resulted in the identification of the four pathways with the highest relevance scores, from which all associated genes were subsequently downloaded. A similar methodology was employed to screen for genes within the Molecular Signatures Database(MSigDB), leading to the selection of four gene sets from the C5 category. By merging the gene lists obtained from both databases and eliminating duplicates, a total of 260 ARGs were compiled.

Transcriptome sequencing data, along with clinical and somatic mutation information about KIRC, were retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The transcriptional data were processed via R software to extract transcripts per million (TPM) data, which encompassed 541 tumor tissue samples and 72 adjacent noncancerous tissue samples. Additionally, data concerning 402 instances of somatic cell mutations and clinical information for 537 patients were organized via Perlsoftware.

Furthermore, the E-MTAB-1980 cohort, which consists of KIRC microarray data, was obtained from the ArrayExpress database(https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/). Clinical information related to this cohort was also sourced from supplementary materials published in the literature11. After thorough collation, transcriptome sequencing data and clinical information for 101 patients were compiled. However, owing to the absence of clinical staging data, the 2017 edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines was employed to supplement the TNM staging information.

A single-cell dataset (GSE159115) was obtained from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). This dataset comprises seven samples of KIRC, one sample of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, and six samples of normal kidney tissue. For quality control, seven KIRC samples were selected for analysis, while two samples exhibiting elevated mitochondrial content were excluded via the “Seurat” package12. The cells characterized by high mitochondrial content (> 5%) and low gene counts (< 300) were subsequently removed, yielding a final total of 9238 high-quality cells for further analysis.

Modeling gene screening

To increase the reliability of the results, genes exhibiting expression in fewer than 30% of the samples within the TCGA-KIRC dataset were excluded from the analysis. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between tumor and normal samples in KIRC were identified via the “limma” package in R software, with statistical analysis conducted via the Wilcoxon test. The criteria established for DEGs included an absolute value of Log Fold Change (Log|FC|) greater than 1 and an adjusted P value of less than 0.05. Next, the TCGA-KIRC cohort data were randomly partitioned into training and validation groups at a 1:1 ratio. The chi-square test was used to assess differences in the composition of count data between the two groups, whereas the Wilcoxon test was used to validate the measured clinical data.

The E-MTAB-1980 cohort was utilized as an independent external validation cohort. The training cohort served for the construction of the risk model, whereas the two validation cohorts were employed to assess the predictive efficacy and generalizability of the model. Univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted on the DEGs via clinical data from the training cohort to identify genes associated with ARGs that are correlated with patient prognosis. The prognosis-related genes were subsequently further analyzed via the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (Lasso) method, which was implemented via the “glmnet” package.

Modeling and validation of risk prediction

A risk-scoring formula was developed utilizing multifactorial Cox regression, from which the regression coefficients for each variable were derived. Additionally, the model underwent optimization through the application of bidirectional stepwise regression during the construction process.The risk assessment model

In this model, βi represents the regression model coefficient, and Expgeneidenotes the expression of the genes included in the model in each sample.

Risk scores were computed for each patient within the training and the two validation cohorts via risk modeling equations. The median score was established as a threshold to classify patients with higher scores into high-risk categories, whereas those with lower scores were classified into low-risk categories. The differences in overall survival (OS) between the high-risk and low-risk groups were assessed through Kaplan‒Meier (K‒M) survival analysis. Additionally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were employed to determine the predictive accuracy of the risk model for patient survival at 1, 3, and 5 years.

An analysis of subgroups about localized and non-localized renal carcinoma

To further assess the adaptability of the risk prognostic model in different stages of tumors, patients were classified into localized renal cancer and non-localized renal cancer based on various stages in TCGA-KIRC. Patients with tumor stages I and II were categorized as the localized renal group. In contrast, those with tumor stages III and IV were classified as the non-localized renal cancer group (locally advanced/metastatic). Within each group, patients were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. First, we plotted the KM survival curves for high-risk and low-risk patients within each group. Then, we depicted the survival curves combining stage and risk. Finally, we plotted the ROC curves predicting the 1, 3, and 5-year survival rates of the risk model for localized and non-localized renal cancer.

Independent prognostic analysis and development of a nomogram model

Univariate Cox regression and multivariate Cox regression analyses were subsequently employed to examine the influence of patient sex, age, stage, and grade. A factor was deemed an independent prognostic factor if it achieved a significance level of P < 0.05 in both analyses. The risk score was subsequently integrated with the independent prognostic factors to develop a nomogram model, which facilitates visual prediction of overall patient survival at 1, 3, and 5 years. Additionally, calibration and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to assess the predictive accuracy of the nomogram.

Analysis of single-cell and intercellular communication

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data were subjected to normalization via the log normalization method, and the most significantly variablefeatures were determined through the application of the “FindVariableFeatures” function. Specifically, the 1500 genes exhibiting the most variable were identified via the “FindVariableFeatures” algorithm. Principal component analysis (PCA) was subsequently conducted, and cell clustering was executed via the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) algorithm, with the resolution for cell clustering set at 0.2. The annotation file associated with the dataset enabled the analysis of cell clusters, with cell types being manually annotated based on this file. The “FindAllMarkers” function was employed to compute the marker genes for each cell cluster, thereby elucidating the clusters in which the modeled genes were predominantly expressed.

In this investigation, we examined the annotated data of 9238 KIRC single cells via the “CellChat” package and incorporated secretory signaling pathway data from the human CellChatDB database13 We elucidated the communication patterns among various cell populations within KIRC tissues and identified the signaling pathways potentially associated with the modeled genes, as well as the principal receptor‒ligand pairs involved in these pathways.

Mutation burden analysis

To examine the disparities in tumor mutation burden (TMB) between the low-risk and high-risk cohorts, mutation data from the TCGA-KIRC database were analyzed via the “maftools” package. This analysis facilitated the identification of key mutated genes and TMB values across the distinct risk groups. Patients were categorized into high and low mutation groups based on the median TMB value. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to assess the differences in TMB between the high-risk and low-risk groups. Furthermore, the Kaplan‒Meier method was applied to evaluate survival differences between the high mutation group and low mutation group, thereby investigating the influence of risk-associated mutation combinations on patient prognosis.

Analysis of immunotherapy and targeted therapy

The tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion (TIDE) effect within the tumor microenvironment is inversely correlated with the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies; a more pronounced TIDE effect is associated with diminished therapeutic outcomes. The TIDE database facilitates the quantitative assessment of the TIDE effect in various samples and enables the prediction of ICB drug responses based on gene expression data. In this investigation, non-localized renal carcinomasamples from the TCGA-KIRC cohort were analyzed via this database. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare TIDE scores between the high-risk and low-risk groups.

Additionally, the “pRRophetic” package was used to predict tumor drug sensitivity based on gene expression profiles. This study leveraged the built-in cgp2016 dataset to assess the effectiveness of axitinib, sunitinib, sorafenib, pazopanib, and temsirolimus within the non-localized renal carcinoma patients. The Wilcoxon test was subsequently applied to evaluate differences in the 50% maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) across various risk groups, and the relationships between risk scores and IC50 values were analyzed via Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Statistical techniques

Perl version 5.30.3 was used to analyze the clinical and mutation data from the TCGA-KIRC dataset, while subsequent data analysis and visualization were conducted via R version 4.1.0. The measurement data were characterized via the interquartile range (IQR), and categorical data are presented as frequencies or percentages (%). The specific statistical methodologies utilized in this study are described in the relevant subsections. The log-rank test was applied for Kaplan‒Meier survival analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Modeling gene screening

Clinical data from the TCGA-KIRC and E-MTAB-1980 cohorts were compiled (Table 1). Differential gene expression analysis revealed 89 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), 21 of which presented low expression levels in tumor tissues, whereas 68 presented high expression levels. The DEGsare visualized via a heatmap (Fig. 1).

The 532 samples from the TCGA-KIRC cohort were randomly allocated into a training group and an internal validation group, adhering to a 1:1 ratio, resulting in 266 samples for each group. An analysis of the clinical indicators revealed no statistically significant differences in the distributions of age (P = 0.076), sex (P = 0.364), tumor grade (P = 0.277), tumor stage (P = 0.625), T stage (P = 0.303), N stage (P = 0.779), or M stage (P = 0.886) between the two groups (Table 2).

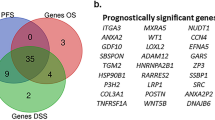

Univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted on the DEGs in the training cohort, yielding 46 genes with significant prognostic associations (Fig. 2A). Following LASSO regression analysis, the variables were further refined, resulting in the selection of an optimal set of genes, which included CDH13, MEOX2, PLG, PROX1, RHOB, SERPINF1, TEK, TIMP1, and VAV3. Ultimately, a total of nine genes were identified for modeling purposes (Fig. 2D).

Modeling gene screening process. (A) Forty-six prognosis-related genes with hazard ratios (HRs) > 1 were associated with poor prognosis in patients, and HRs < 1 indicated protective genes. (B) The horizontal axis represents the value of the independent variable lambda, whereas the vertical axis represents the coefficients of the independent variable. (C) The relationship between partial likelihood deviance and log(λ) was plotted via the LASSO regression model. (D) Visualization of gene expression differences used for modeling. ***P < 0.001.

Risk modeling and validation

A predictive model for risk scores was constructed via multivariate Cox regression, and a two-way stepwise regression algorithm was applied to optimize the model during its construction.

Using the scoring formulas, risk scores were computed for each sample within the training group, validation group, and E-MTAB-1980 cohort, with median scores serving as thresholds for the classification of samples into high-risk and low-risk categories.

Initially, Kaplan‒Meier survival curves were generated for the training group (Fig. 3A), revealing a statistically significant disparity in survival outcomes between the high-risk and low-risk groups (P < 0.001), with patients classified in the high-risk group exhibiting markedly poorer prognoses. A scatter plot illustrating the correlation between risk scores and patient survival further demonstrated a higher mortality rate among high-risk patients (Fig. 3B). Additionally, a ROC curve was constructed to evaluate the model’s predictive efficacy, yielding area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.798, 0.764, and 0.763 for the predictions of 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival, respectively, indicating a high level of accuracy in the model’s predictions (Fig. 3C).

Risk modeling and validation training cohort: A,B,C; validation group: D,E,F; E-MTAB-1980 cohort, G, H,I. Survival analysis (A, D, G) indicated that the prognosis for high-risk patients was significantly poorer. In the accompanying scatterplot, delineated by a dotted line, higher risk scores correspond to high-risk patients. The mortality rate among high-risk patients is elevated across all cohorts (B, E, H). Additionally, C, F, and I present the time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for each cohort, where a higher area under the curve (AUC) value signifies an improved predictive capability of the model.

To further evaluate the robustness and generalizability of the predictive model, Kaplan‒Meier curves and ROC curves were generated for both the validation group and the E-MTAB-1980 cohort, confirming that the model’s predictive capabilities consistently remained strong across these additional datasets.

The efficacy of risk models in predicting outcomes across various staging subgroups

In the cohort of patients with localized renal cancer (P = 0.032) and those with non-localized renal cancer (P < 0.001), the prognosis for the low-risk group was significantly more favorable compared to the high-risk group (Fig. 4A,B). A combined analysis of risk and staging indicated notable prognostic disparities among the groups, with the low-risk cohort in localized renal cancer exhibiting the most favorable outcomes. In contrast, high-risk patients with non-localized renal cancer demonstrated the poorest prognosis (Fig. 4C). In the context of localized renal cancer, the area under the curve (AUC) for predicting survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years using this risk model was 0.773, 0.650, and 0.617, respectively. Conversely, in the group with locally advanced or metastatic disease, the AUC values were 0.691, 0.709, and 0.773 (Fig. 4D,E). These findings suggest that the risk model may offer reliable prognostic predictions for localized and advanced or metastatic renal cancer, with a particular advantage in forecasting outcomes for advanced or metastatic cases.

Independent prognostic variables for the development of a column‒line diagram model

Independent prognostic factors for patients, including the risk score, tumor stage, grade, and age, were identified (Fig. 5A,B). To evaluate the predictive efficacy of these factors, we integrated them into a nomogram model and subsequently generated ROC curves and calibration curves for validation purposes (Fig. 6A). The AUC values for the ROC curves at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years were 0.864, 0.816, and 0.789, respectively, indicating that the predictive capability of the nomogram model is commendable (Fig. 6B). Further analysis of various indices through ROC curve plotting revealed that the nomogram model exhibited the highest predictive performance (Fig. 6C). Additionally, the calibration curves for the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year predictions demonstrated a strong alignment between the model’s predictions and actual outcomes, thereby fulfilling the objective of accurately forecasting patient prognosis (Fig. 6D–F).

Nomogram modeling and performance testing: (A) Thenomogram serves as a predictive tool for estimating the overall survival rates of patients at 1, 3, and 5 years, based on the cumulative scores. The time-dependent ROC curve indicates that a higher AUC correlates with increased nomogram (B) prediction accuracy. (C) ROC curves for multivariate, with nomogram modelshowing higher predictive accuracy than other factors from AUC values.Additionally, the calibration curves for the nomogram model (D, E, and F) illustrate the model’s performance; the diagonal dashed line represents the ideal prediction outcome, whereas the red line reflects the actual prediction results of the nomogram.

Single-cell analysis and cellular communication analysis

Single-cell analysis

For the analysis, five high-quality single-cell datasets were selected (Fig. 7A). The data were dimensionalized using PCA analysis and 15 major feature groups were extracted, after which all cells were classified into 16 different cell populations (Fig. 7B, D). Following manual annotation, the identified cell types included macrophages, tumor cells, vascular endothelial cells, uncategorized endothelial cells, pericytes, vascular smooth muscle cells (vSMCs), T cells, and plasma cells. The uncategorized endothelial cells were consolidated into endothelial cell types to facilitate further analysis.

Single-cell analysis of KIRC: The analysis of single cells was conducted on the five included samples (A) Single-cell data were categorized into 16 distinct cell clusters (B). Bubble plots illustrate the modeled gene expression within each cell cluster (C), with larger circles representing higher expression levels within a cell cluster and darker colors indicating elevated expression levels.The number of cells within each cluster was also quantified (D).

The categorical statistics of the annotated cell types (Fig. 7D) revealed that tumor cells constituted 29.5% (2726/9238) of the total cell population, whereas endothelial-like cells (including endothelial cells and pericytes) represented 32.8% (3033/9238). Vascular smooth muscle cells accounted for 14.9% (1371/9238), and immune cells (comprising macrophages, plasma cells, and T cells) made up 22.8% (2108/9238). This distribution highlights the variety of cell types present within the KIRC microenvironment.

Subsequently, bubble plots were generated to identify the cell clusters exhibiting high expression levels of the modeled genes (Fig. 7C). The PLG genes were predominantly expressed in tumor cell clusters, whereas the TEK genes were more highly expressed in pericytes. Conversely, the TIMP1 gene was expressed across multiple cell clusters, with the most pronounced expression observed in vascular smooth muscle cells. The MEOX2 and PROX1 genes presented high expression in specific cell clusters, although their overall expression levels across all clusters were relatively low.

Cell communication analysis

To investigate the patterns of cellular communication within the microenvironment of KIRC, this study employed annotated single-cell data for the analysis of intercellular interactions. Initially, the quantity (Fig. 8A) and intensity (Fig. 8B) of intercellular communication within KIRCs are illustrated. A total of seven cell types were identified as ligands capable of transmitting signals to facilitate intercellular communication, and these same cell types also function as receptors to receive signals from other cells. Notably, tumor cells, vascular endothelial cells, and other cell types exhibited the most substantial levels of communication, both in terms of quantity and intensity. Furthermore, we identified the 15 most prominent intercellular communication patterns (Table 3), with the MIF pathway, which involves tumor cells acting as ligands and macrophages acting as receptors, demonstrating the highest probability of occurrence among the various intercellular communications.

Analysis of KIRC cell communication: (A) Graph of the number of cellular communications; the thickness of the connecting lines is related to the number of intercellular communications; the thicker the connecting lines are, the greater the number of intercellular communications is, and the arrows of the connecting lines point in the direction of signaling. (B) Intensity of the cellular communication graph; the thicknesses of the lines and the arrows have the same meaning as before.

Subsequent analyses revealed that the modeling gene TEK is involved in the angiogenesis-related “ANGPT” pathway, wherein vascular endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and pericytes function as signaling entities to modulate the activity of vascular endothelial cells and pericytes (Fig. 9A). Notably, the three types of immune cells, along with tumor cells, were not found to participate in this pathway. Furthermore, an examination of three principal ligand‒receptor pairs revealed their roles in signaling (Fig. 9B), namely, ANGPT2-(ITGA5 + ITGB1), ANGPT2‒TEK, and ANGPT1‒TEK, with ANGPT2‒ITGA5 + ITGB1) demonstrating the most significant contribution within this pathway. Additionally, the expression levels of the ligand-encoding genes were assessed (Fig. 9C). The ligand ANGPT1 was expressed predominantly in vSMCs, whereas ANGPT2 was expressed primarily in endothelial cells, vSMCs, and pericytes. The receptors TEK and ITGA5 were highly expressed in both endothelial cells and pericytes, whereas ITGB1 was broadly and abundantly expressed across all cell types. The modes of intercellular communication involving each ligand‒receptor pair are also graphically represented (Fig. 9D, E, F).

Analysis of the angiogenic “ANGPT” pathway: (A) Heatmap of cell-to-cell communication within the “ANGPT” signaling pathway, with vertical coordinates indicating the sending cells and horizontal coordinates indicating the receiving cells; (B) Levels of the contribution of major receptor‒ligand pairs within the signaling pathway, with the interaction between the ligand ANGPT2 and the receptor (ITGA5 + ITGB1) being the most dominant; (C) Receptor‒ligand gene expression in each endocytosis; the cellular communication network involves the different ligand‒receptor pairs (D, E, F).

Gene mutations and prognosis

The findings from the somatic mutation analysis of KIRC indicated that the 20 genes exhibiting the most significant mutations were consistent across both the high-risk and low-risk groups (Fig. 10A, B), with the VHL gene identified as the most frequently mutated gene in both cohorts. Furthermore, the TMB in patients classified as high-risk was markedly elevated compared with that in their low-risk counterparts (P = 0.04) (Fig. 10C). Additionally, patients in the high mutation group had a significantly poorer prognosis (P < 0.001) (Fig. 10D). Further analysis revealed that patients categorized as high risk with high mutation rates experienced the most unfavorable prognosis, whereas those classified as low risk with low mutation rates presented the most favorable outcomes (Fig. 10E).

Somatic mutation analysis: Analysis of the top 20 genes with the highest mutation rates in the KIRC high- and low-risk groups (A, B); Violin plots of TMB differences between the high- and low-risk groups (C); prognostic impact of gene mutations (D); K‒M curves for risk-combined mutations, with the worst prognosis in the high-mutation population of high-risk patients (E).

Immunotherapy and targeted therapy prediction

In this study, we employed the TIDE database to derive the TIDE score for each sample. Statistically significant findings were observed (Fig. 11A), indicating that the TIDE scores of patients classified in the high-risk group were markedly elevated compared with those in the low-risk group (P < 0.001). This observation suggests that in patients with high-risk, progressive, or metastatic renal tumors, there may be significant immune dysfunction or immune exclusion occurring within the tumor microenvironment. Such conditions could potentially result in a diminished efficacy of immunotherapeutic interventions.

Furthermore, our analysis reveals a statistically significant disparity in the IC50 values of sorafenib between high-risk and low-risk cohorts in cases of non-limited clear cell renal carcinoma (P = 0.008) (Fig. 11B,C). The IC50 values exhibit a positive correlation with the risk score (R = 0.18, P = 0.009), suggesting that patients with elevated risk scores necessitate higher dosages of the medication to attain therapeutic efficacy. Consequently, patients classified as low risk with advanced or metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma demonstrate greater sensitivity to sorafenib.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of KIRC is multifaceted, with various acquired risk factors, such as smoking and obesity, as well as hereditary predispositions contributing to the onset of kidney cancer. Notable genetic alterations associated with KIRC include the deletion of the short arm of chromosome 3 and mutations in several key genes, including VHL, PBRM1, BAP1, SETD2, and MTOR14.Among these, mutations in the VHL gene are particularly prevalent and play a critical role in the regulation of HIFs, which are essential for tumor angiogenesis15. Under normoxic conditions, the proline hydroxylase domain (PHD) hydroxylates HIF-1α, and VHL facilitates the ubiquitination of hydroxylated HIF-1α, rendering it susceptible to proteolytic degradation16. Conversely, during hypoxic conditions or in the presence of VHL mutations, the hydroxylation, ubiquitination, and subsequent degradation of HIF-1α are disrupted. This allows HIF-1α to dimerize with the HIF-1β subunit in the nucleus, forming an active transcriptional complex that activates the expression of numerous genes involved in cell survival, metabolism, and angiogenesis17. Experimental evidence supports this mechanism; for example, the reintroduction of wild-type VHL into VHL-deficient renal cancer cell lines resulted in significant inhibition of tumor cell proliferation in vitro18.

The phenomenon of tumor angiogenesis was first described by Folkman in 1971, who suggested that the growth and metastasis of tumors are contingent upon angiogenesis, suggesting that the inhibition of angiogenesis could represent a novel therapeutic approach for tumor management19. The rapid metabolic activity associated with tumor proliferation frequently induces hypoxic conditions within the tumor microenvironment, disrupting the equilibrium between proangiogenic and antiangiogenic processes, thereby leading to the upregulation of proangiogenic factors within tumor cells6. Tumor angiogenesis is mediated by a variety of factors and signaling pathways, including HIF, VEGF, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and the angiopoietin (Ang)-Tie2 signaling pathway20.

Currently, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, which are employed in the treatment of advanced renal cancer, primarily target angiogenesis. By inhibiting angiogenic processes, these agents impede the ability of tumors to acquire essential nutrients, thereby achieving a degree of tumor starvation that can enhance patient prognosis21.

Despite the importance of tumor angiogenesis in the prognosis of kidney cancer patients, there is a paucity of research in this area, and individualized treatment protocols for drug selection in advanced kidney cancer patients remain limited. In the present study, we employed ARGs to develop a robust predictive model for the prognosis of patients with kidney KIRC. Five genes (MEOX2, PLG, PROX1, TEK, and TIMP1) were identified as model genes, and the risk models constructed from these genes demonstrated commendable and consistent performance.

In subsequent investigations, we employed single-cell data from the KIRC dataset GSE159115 to elucidate the diverse cell types present within the tumor microenvironment, including macrophages, tumor cells, and vascular endothelial cells, along with their respective proportions. This analysis contributes to a deeper understanding of the roles played by various cell types in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis22. By identifying the elevated expression of specific modeling genes across different cell clusters—such as PLG in tumor cell clusters, TEK in pericytes, and TIMP1 in vascular smooth muscle cells—we delineated the cellular localization of these genes’ functions. This work establishes a foundational basis for further exploration of the relationship between gene expression and tumor cell behavior.The analysis of cell communication has elucidated the quantity and intensity of intercellular interactions within KIRC, highlighting the significance of communication among tumor cells, vascular endothelial cells, and other cellular entities. Distinct intercellular communication patterns and high-probability macrophage MIF pathways have been identified, which are essential for comprehending the interactions between tumor cells, immune cells, and vascular cells. This indicates that tumor cells may modulate the functions of immune cells, such as macrophages, through specific signaling pathways, thereby influencing the tumor immune microenvironment and, in turn, tumor metastasis and resistance to therapeutic agents. The TEK gene, which is implicated in the angiogenesis pathway associated with ANGPT, is predominantly expressed in pericytes, and its involvement in this pathway is intricately linked to angiogenesis, which subsequently affects tumor prognosis. This elucidates the mechanism by which TEK, as a modeling gene, impacts prognostic outcomes. Furthermore, it offers potential cellular and molecular mechanisms through which other genes within the model may influence prognosis, thereby enhancing the biological rationale of the prognostic model and improving the accuracy and reliability of prognostic assessments in KIRC.

Mesenchyme homeobox 2 (MEOX2) is a member of the homeobox gene family and functions as a nuclear transcription factor recognized for its role as a growth inhibitor in vascular smooth muscle cells and vascular endothelial cells23. Research indicates that the overexpression of MEOX2 impedes the growth and migration of vascular endothelial cells by increasing the expression of cell cycle protein-dependent kinase inhibitors and inactivating the NF-κB signaling pathway24. Furthermore, MEOX2 has been implicated in the prognostic evaluation of various cancers; for example, in lung cancer, its overexpression is correlated with chemoresistance and overall prognosis25, whereas lower levels of MEOX2 expression are associated with reduced survival rates in patients with hepatocellular and laryngeal cancers26. There is a paucity of research regarding the MEOX2 gene in clear cell renal carcinoma; however, the literature suggests that MEOX2 may function as an oncogene in nephroblastoma (Wilms tumor), with its deletion leading to accelerated angiogenesis and increased Wnt signaling, potentially contributing to Wilms tumor progression27. In the present study, MEOX2 exhibited relatively high expression levels in tumor tissues and was identified as a prognostic risk factor for patients. Single-cell analysis demonstrated that, despite its high expression within the vSMC and pericyte clusters, the overall expression ratio in the broader cell populations was low, indicating that further investigation into its role in angiogenesis and clear cell carcinoma is warranted.

Fibrinogen (PLG), commonly referred to as plasminogen, serves as a significant cell surface-bound zymogen within the context of fibrinolysis28. The components of the plasminogen‒fibrinolytic system play crucial roles in various physiological and pathological processes across organisms, particularly by modulating angiogenesis and cell migration. These processes include coagulation, cancer cell invasion, and metastasis. Notably, components of this system are frequently found in the majority of tumors, with their expression being regulated dually by cytokines and growth factors and exhibiting upregulation in numerous cancer types29. In the present study, the PLG gene presented relatively high expression levels in normal renal tissues; conversely, its elevated expression in tumor tissues was associated with a more favorable prognosis for patients. Furthermore, single-cell analysis indicated that PLG was predominantly expressed in specific clusters of tumor cells.

The protein encoded by the Prospero-related homeobox 1 (PROX1) gene functions as a transcription factor that is crucial for the development of lymphatic vessels in animal embryos. Knockout studies conducted in murine models have demonstrated that a deficiency in PROX1 typically results in an inability to differentiate the endothelial cells of lymphatic ducts. Conversely, elevated levels of PROX1 expression are associated with enhanced lymphatic vessel formation, which has significant pathological implications for cancer-related lymph node metastasis30. There is a growing body of evidence highlighting the critical role of the PROX1 gene across various cancer types. In patients with neuroblastoma, increased nuclear expression of PROX1 is correlated with a greater proportion of undifferentiated or poorly differentiated cells, which in turn is linked to an increased likelihood of lymphatic metastasis and a poorer prognosis31. In the context of hepatocellular carcinoma, PROX1 has been shown to increase the stability of the transcription factor HIF-1α by recruiting histone deacetylase (HDAC1), thereby facilitating epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT) in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Tumors that undergo EMT are more prone to metastasis and are associated with a worse prognosis32. Furthermore, a study established a biomarker for assessing the progression and prognosis of KIRC on the basis of PROX1 expression. While PROX1 levels in tumor tissues were lower than those in adjacent normal tissues were, relatively high levels of PROX1 expression were significantly linked to poor prognostic outcomes. In vitro experiments indicated that cell lines overexpressing PROX1 presented a more aggressive phenotype33. In the present study, although PROX1 was found to be expressed at low levels in tumor tissues, its relatively high expression was identified as a risk factor for patient prognosis, which aligns with the literature.

TEK (Tie2) is a receptor tyrosine kinase predominantly expressed in endothelial cells that plays a crucial role in vascular regeneration and homeostasis. The Ang-Tie signaling pathway is implicated in various processes, including tumor metastasis and angiogenesis34. Researchers have developed a range of novel therapeutic agents that specifically target this pathway, which not only inhibits tumor angiogenesis but also addresses the interplay between angiogenesis and inflammation. This approach aims to mitigate the challenges associated with drug resistance and the low response rates observed with traditional TKIs35. Furthermore, studies involving the knockdown of TEK expression in KIRC have demonstrated an increase in tumor cell proliferation and migration. Subsequent investigations revealed that TEK may promote apoptosis and inhibit cell growth through the regulation of protein kinase B (AKT) phosphorylation36.

In this study, TEK was found to be expressed at relatively low levels in tumor tissues, serving as a protective factor for patients with kidney cancer. Further analysis at the single-cell level indicated that TEK was predominantly expressed in pericytes. Investigations into cellular communication revealed that this gene is involved primarily in the angiogenic pathway known as “ANGPT” (i.e., Ang-Tie). The principal ligands in this pathway are Ang1 and Ang2, with Tie2 serving as the main receptor34. Notably, the functions of these two ligands differ significantly: Ang1 functions as an agonist of Tie2, promoting receptor phosphorylation and activating downstream signaling pathways that contribute to the maintenance of vascular homeostasis. Conversely, under hypoxic conditions, Ang2 is upregulated by HIF and acts as an antagonist of Ang1, inhibiting receptor phosphorylation by binding to Tie2. This antagonistic action leads to elevated expression of the gene in pericytes, resulting in an imbalance in vascular homeostasis, increased vascular permeability, and increased angiogenesis34. Furthermore, high levels of Ang1 are predictive of a favorable prognosis in patients with head and neck tumors, whereas elevated levels of Ang2 and a high Ang2/Ang1 ratio correlate with poorer prognoses in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer37.

Current research indicates that the Ang-Tie2 signaling pathway plays a critical role in tumor neovascularization. Consequently, researchers have developed a range of innovative antivascular agents aimed at this pathway, including AMG 386 and CVX-241. AMG 386 is an Fc fusion protein derived from bioactive peptides of the Fc region of immunoglobulin G (IgG). This agent functions by obstructing the interactions between Ang1, Ang2, and the Tie2 receptor, thereby inhibiting the process of angiogenesis38. In a phase II clinical trial involving patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, the combination of AMG386 and paclitaxel enhanced progression-free survival39; however, further assessment is necessary to establish the broader applicability of this drug.On the other hand, CVX-241 is a bispecific peptide-coupled antibody that employs chemical coupling to link two distinct peptides to a foundational antibody, enabling simultaneous targeting of VEGF and Ang2 to impede angiogenesis40. To date, the literature has only documented its efficacy in preclinical models of colon and breast cancer, with no clinical trial data currently available.

The ANGPT2-(ITGA5 + ITGB1) receptor‒ligand pair was subsequently determined to be the most significant contributor to the “ANGPT” pathway. Integrin α5β1 (ITGA5 + ITGB1), commonly referred to as the fibronectin receptor, plays a crucial role in tumor metastasis, cellular proliferation, and tumor-associated angiogenesis41. It has been identified as a proangiogenic factor that interacts with VEGF and angiopoietin-Tie2 to modulate tumor angiogenesis42. We propose that the ANGPT2-(ITGA5 + ITGB1) receptor‒ligand interaction within the ANGPT pathway is instrumental in the progression of KIRC and may represent a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

The tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) family comprises four paralogous genes: TIMP1, TIMP2, TIMP3, and TIMP4. These genes play significant roles in various biological processes, including antiapoptotic mechanisms, antiangiogenic activities, regulation of the cell cycle, and differentiation of epithelial or blood-derived cells43. Among these, TIMP1 is a prominent member of the TIMP family, and the literature indicates that elevated levels of TIMP1 expression in tissues or blood are associated with unfavorable prognoses across multiple tumor types. Specifically, TIMP1 has been shown to facilitate tumor progression and inhibit apoptosis via the PI3K/AKT and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in colon cancer44. Gong45 reported that increased TIMP1 expression is correlated with poor outcomes in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that TIMP1 is significantly overexpressed in renal tumor tissues and cell lines, which correlates with adverse patient prognoses. In vitro experiments indicated that silencing TIMP1 expression effectively impeded the growth and invasion of renal cell carcinoma. Subsequent experimental validation led to the hypothesis that TIMP1 may promote renal cancer progression through the epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT) signaling pathway46. This study identified TIMP1 as a highly expressed gene in tumor tissues, serving as a negative prognostic indicator for patients. Additionally, single-cell analysis revealed that TIMP1 expression was predominantly localized in vSMC clusters. In summary, this research established a reliable risk assessment model comprising five genes.

KIRC is characterized by a significant degree of immune infiltration. During the “cytokine era,” advanced renal cancer patients are frequently treated with interferon at moderate to high doses as a first-line therapeutic approach; however, the objective response rate is limited, ranging from 5 to 7%47. Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies are designed to increase the ability of the immune system to identify and target cancer cells. Since 2015, the effectiveness of ICBs has been substantiated through numerous clinical trials, leading to benefits for many patients with metastatic renal cancer. Nevertheless, only approximately one-third of patients respond to ICB-based therapies. Two primary mechanisms contributing to the suboptimal response rates to ICBs are immune dysfunction and immune rejection48. In the present study, we employed the TIDE scoring system to assess immune dysfunction and rejection levels. Our results indicate that the TIDE scores for the high-risk cohort of non-localized clear cell renal carcinoma are markedly elevated compared to those in the low-risk cohort. This suggests that patients with low-risk KIRC are more likely to benefit from immunotherapeutic interventions.

In conclusion, we conducted an analysis of five frequently utilized targeted therapy agents for advanced or metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Among these, only sorafenib demonstrated a statistically significant disparity in treatment efficacy between high-risk and low-risk patient populations. Furthermore, it was observed that as the risk score escalated, the IC50 value of the drug correspondingly increased. This finding suggests that low-risk patients with non-localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma experience more favorable treatment outcomes when administered sorafenib.

Conclusions

In this investigation, five genes associated with angiogenesis were identified through methodologies such as differential expression analysis and Cox regression with Lasso regularization. The resulting prognostic prediction model for KIRC demonstrated robust performance, revealing that patients classified as high-risk exhibited a significantly poorer prognosis than their low-risk counterparts did. Furthermore, a nomogram model was developed, integrating various independent prognostic factors, which effectively visualized and accurately predicted the overall survival rates of patients. Ultimately, the analysis of treatment responses indicates that patients classified within the high-risk category of locally advanced or metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma demonstrate pronounced immune dysfunction and rejection phenomena. These factors may contribute to suboptimal immune responses to immunotherapy. Conversely, in the context of targeted therapy for progressive or metastatic tumors, patients identified as low risk may exhibit heightened sensitivity to sorafenib.

Data availability

The datasets produced and examined in the current research are accessible to the public through the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), ArrayExpress (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/), and the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). If you have any questions regarding data access, interested individuals are encouraged to contact the corresponding authors for further assistance.

Abbreviations

- KIRC:

-

Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- ARGs:

-

Angiogenesis-related genes

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- ICB:

-

Immune checkpoint blockade

- TKIs:

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

References

Padala, S. A. et al. Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. World J. Oncol. 11(3), 79–87 (2020).

Shuch, B. et al. Understanding pathologic variants of renal cell carcinoma: distilling therapeutic opportunities from biologic complexity. Eur. Urol. 67(1), 85–97 (2015).

Motzer, R. J. et al. Kidney Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 20(1), 71–90 (2022).

Choueiri, T. K. & Motzer, R. J. Systemic Therapy for Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med. 376(4), 354–366 (2017).

Carmeliet, P. & Jain, R. K. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature 407(6801), 249–257 (2000).

Rajabi, M. & Mousa, S. A. The role of angiogenesis in cancer treatment. Biomedicines 5(2), 34 (2017).

Teleanu, R. I., Chircov, C., Grumezescu, A. M. & Teleanu, D. M. Tumor angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic strategies for cancer treatment. J. Clin. Med. 9(1), 84 (2019).

Singh, D. Current updates and future perspectives on the management of renal cell carcinoma. Life Sci. 264, 118632 (2021).

Karaman, S., Leppanen, V. M. & Alitalo, K. Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in development and disease. Development 145(14), dev151019 (2018).

Mahalingam, D. et al. Vorinostat enhances the activity of temsirolimus in renal cell carcinoma through suppression of survivin levels. Clin. Cancer Res. 16(1), 141–153 (2010).

Sato, Y. et al. Integrated molecular analysis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 45(8), 860–867 (2013).

Hao, Y. et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184(13), 3573-3587 e3529 (2021).

Jin, S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using Cell Chat. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 1088 (2021).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Analysis Working Group. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature 499(7456), 43–49 (2013).

Hsieh, J. J. et al. Chromosome 3p Loss-Orchestrated VHL, HIF, and epigenetic deregulation in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 36(36), JCO2018792549 (2018).

Kietzmann, T., Mennerich, D. & Dimova, E. Y. Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) and phosphorylation: Impact on stability, localization, and transactivity. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 11 (2016).

Manalo, D. J. et al. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial cell responses to hypoxia by HIF-1. Blood 105(2), 659–669 (2005).

Cowey, C. L. & Rathmell, W. K. VHL gene mutations in renal cell carcinoma: Role as a biomarker of disease outcome and drug efficacy. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 11(2), 94–101 (2009).

Folkman, J. Tumor angiogenesis: Therapeutic implications. N Engl. J. Med. 285(21), 1182–1186 (1971).

Carmeliet, P. & Jain, R. K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473(7347), 298–307 (2011).

Loges, S., Schmidt, T. & Carmeliet, P. Mechanisms of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy and development of third-generation anti-angiogenic drug candidates. Genes Cancer 1(1), 12–25 (2010).

Zvirblyte, J. et al. Single-cell transcriptional profiling of clear cell renal cell carcinoma reveals a tumor-associated endothelial tip cell phenotype. Commun. Biol. 7(1), 780 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. MEOX2-mediated regulation of Cathepsin S promotes cell proliferation and motility in glioma. Cell Death Dis. 13(4), 360 (2022).

Douville, J. M., Cheung, D. Y., Herbert, K. L., Moffatt, T. & Wigle, J. T. Mechanisms of MEOX1 and MEOX2 regulation of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p16 in vascular endothelial cells. PLoS ONE 6(12), e29099 (2011).

Armas-Lopez, L. et al. Epigenomic study identifies a novel mesenchyme homeobox2-GLI1 transcription axis involved in cancer drug resistance, overall survival and therapy prognosis in lung cancer patients. Oncotarget 8(40), 67056–67081 (2017).

Zhou, P. et al. Growth arrest-specific homeobox is associated with poor survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Med. Oncol. 29(5), 3063–3069 (2012).

Ohshima, J. et al. Two candidate tumor suppressor genes, MEOX2 and SOSTDC1, identified in a 7p21 homozygous deletion region in a Wilms tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 48(12), 1037–1050 (2009).

Hu, Z. G. et al. PLG inhibits Hippo signaling pathway through SRC in the hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular-carcinoma progression. Am. J. Transl. Res. 13(2), 515–531 (2021).

Kwaan, H. C. & McMahon, B. The role of plasminogen-plasmin system in cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 148, 43–66 (2009).

Srinivasan, R. S. et al. The nuclear hormone receptor Coup-TFII is required for the initiation and early maintenance of Prox1 expression in lymphatic endothelial cells. Genes Dev. 24(7), 696–707 (2010).

Ramani, P., Norton, A., Somerville, M. S. & May, M. T. PROX1 lymphatic density correlates with adverse clinicopathological factors, lymph node metastases and survival in neuroblastomas. J. Neurooncol. 108(3), 375–383 (2012).

Liu, Y. et al. PROX1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation and sorafenib resistance by enhancing beta-catenin expression and nuclear translocation. Oncogene 34(44), 5524–5535 (2015).

Lv, T. et al. Impact of an altered PROX1 expression on clinicopathology, prognosis and progression in renal cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 9(5), e95996 (2014).

Huang, H., Bhat, A., Woodnutt, G. & Lappe, R. Targeting the ANGPT-TIE2 pathway in malignancy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10(8), 575–585 (2010).

Herbst, R. S. et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antitumor activity of AMG 386, a selective angiopoietin inhibitor, in adult patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 27(21), 3557–3565 (2009).

Chen, S. et al. The immune-related biomarker TEK inhibits the development of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) by regulating AKT phosphorylation. Cancer Cell Int. 21(1), 119 (2021).

Ahmad, S. A. et al. The effects of angiopoietin-1 and -2 on tumor growth and angiogenesis in human colon cancer. Cancer Res. 61(4), 1255–1259 (2001).

Neal, J. & Wakelee, H. AMG-386, a selective angiopoietin-1/-2-neutralizing peptibody for the potential treatment of cancer. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 12(4), 487–495 (2010).

Mita, A. C. et al. Phase 1 study of AMG 386, a selective angiopoietin 1/2-neutralizing peptibody, in combination with chemotherapy in adults with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 16(11), 3044–3056 (2010).

Doppalapudi, V. R. et al. Chemical generation of bispecific antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 107(52), 22611–22616 (2010).

Hou, J., Yan, D., Liu, Y., Huang, P. & Cui, H. The roles of integrin alpha5beta1 in human cancer. Onco. Targets Ther. 13, 13329–13344 (2020).

Li, L. et al. An angiogenic role for the alpha5beta1 integrin in promoting endothelial cell proliferation during cerebral hypoxia. Exp. Neurol. 237(1), 46–54 (2012).

Grunwald, B., Schoeps, B. & Kruger, A. Recognizing the molecular multifunctionality and interactome of TIMP-1. Trends Cell Biol. 29(1), 6–19 (2019).

Song, G. et al. TIMP1 is a prognostic marker for the progression and metastasis of colon cancer through FAK-PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 35(1), 148 (2016).

Cheng, G. et al. Higher levels of TIMP-1 expression are associated with a poor prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 15(1), 30 (2016).

Shou, Y. et al. TIMP1 indicates poor prognosis of renal cell carcinoma and accelerates tumorigenesis via EMT signaling pathway. Front. Genet. 13, 648134 (2022).

Sharma, P., Hu-Lieskovan, S., Wargo, J. A. & Ribas, A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell 168(4), 707–723 (2017).

Jiang, P. et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 24(10), 1550–1558 (2018).

Funding

The research presented in this paper did not receive financial support from any organization or individual.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data collection: Yuhe Zhou, Chengshuai Yu, Qirui He, Guofeng Yu; Data analysis: Yuhe Zhou, Qirui He, Wenpu Chen, Weixiong Ma; Study design and drafting of the manuscript: Yuhe Zhou, Hengda Hu, Weixiong Ma; Study concept, design, and revision of the manuscript: Hengda Hu and Weixiong Ma.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The data utilized in this study were sourced exclusively from publicly accessible online databases, and the research did not entail any experiments involving animals or humans; therefore, approval from an ethical review board was not necessary.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Ma, W., Hu, H. et al. Angiogenesis related gene signatures predict prognosis and guide therapeutic strategies in renal clear cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 17030 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02134-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02134-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A radiogenomics biomarker based on tumor angiogenesis for non-invasive prognosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Clinical and Translational Oncology (2025)