Abstract

Parental metabolic syndrome (MetS) is associated with increased cardiometabolic risk in offspring, yet the distinct impacts of maternal versus paternal MetS remain poorly understood. Evidence on sex-specific susceptibility during adolescence is particularly limited, despite this being a critical period for the development of chronic metabolic conditions. Using a comprehensive dataset of 5,245 patients selected from a nationally representative database, we examined the differential association of maternal and paternal MetS with cardiometabolic outcomes in adolescent offspring and their variation by offspring sex. Overall, paternal MetS was associated with higher triglyceride and lower HDL cholesterol in male offspring. In contrast, maternal MetS was linked to higher triglyceride levels in both sexes, with additional associations with elevated systolic blood pressure and lower HDL cholesterol only in males. The odds of MetS and its components were most elevated in male adolescents in both paternal and maternal MetS. In conclusion, paternal MetS appeared to exert a stronger influence, particularly in male adolescents. Our findings suggest that both parental and offspring sexes modify the intergenerational transmission of metabolic risk; it is crucial to consider both parental and offspring sexes for effective screening and the prevention of MetS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a condition that involve multiple cardiometabolic risk factors and is gaining attention in public health research because of its increasing prevalence worldwide1,2,3. Especially in the past few years during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea, the prevalence of MetS has increased in children and adolescents as children have gained more weight and lived a more sedentary lifestyle4. Early onset of MetS in childhood is associated with adverse effects on the metabolism of the endocrine and cardiovascular system, such as chronic inflammation, atherosclerosis, and insulin resistance5,6. The prolonged exposure to these adverse conditions leads to an increased risk of severe chronic or critical morbidity beginning from an earlier stage of life7,8, providing a critical reason to begin adequate screening and preventive measures at a younger age.

However, establishing a strategy for screening for MetS in children is challenging because there is no widely accepted definition for MetS in children, unlike the relatively unified definition established for adults9. The mainstream definitions of MetS in children are currently suggested by the International Diabetes Federation and the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP), each of which focuses on different metabolic aspects, ranging from central obesity to insulin resistance10. This disparity in the definition of MetS comes from the volatile nature of children’s metabolism, which is affected by multiple hormonal changes as they age and grows11,12.

In addition to the children’s metabolic complexities, the multifactorial characteristics of MetS, including the interrelationship between environmental and genetic factors, have been suggested. Environmental factors such as family socioeconomic status13, diet14, and physical activity15 have been identified as pivotal factors in children’s poor cardiometabolic health outcomes and the development of MetS. In fact, based on these studies, the current preventive strategies for MetS focus on lifestyle aspects16. However, multiple studies have studied the segregation pattern of MetS within families, suggesting the inheritance potential of the disease11,12. Obese parents have been shown to cause early-onset obesity in their children17. These children also frequently exhibit poor metabolic profiles, such as insulin resistance17 and elevated blood pressure18. Recent studies have also increasingly identified genetic factors associated with cardiometabolic risk factors, including obesity and diabetes mellitus19,20. Most importantly, Song K et al. proposed that even in children who are not obese and have relatively favorable environmental factors, the presence of parental MetS increases the risk of MetS21.

This study, thus, aimed to deepen our understanding of how parental MetS may influence adolescent metabolic outcomes, with a focus on potential sex-specific genetic contributions. While many studies provide the relationship between the parental MetS and MetS in their offspring, the differential impact of maternal and paternal MetS on male versus female offspring have yet to be deeply understood. A comprehensive understanding of inheritance patterns, distinguishing whether the influence originates from the father or the mother, is imperative to elucidate the transmission of MetS risk across generations. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the influences of parental MetS on the metabolic aspects of offspring in Korea, with a focus on the impact of the sex of both parents and their offspring. Our findings raise the possibility for different familial, genetic, and environmental influences to be exerted on offspring and the importance in their consideration in screening for MetS in children.

Materials and methods

Design

This retrospective, cross-sectional study utilized the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) database from 2007 to 2020. This national survey system has been conducted since 1998 and includes comprehensive data on various health indicators, lifestyle factors, and dietary habits. The survey ensured that informed consent was received from every participant, adhering to ethical research standards22. Since the database is publicly available and does not include identifiable information, we proceeded with the study under the exemption from review granted by the Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Hospital (AJOUIRB-EX-2024-447).

Study population

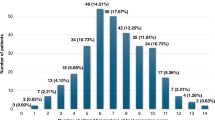

Among the initial 113,091 participants of the KNHANES, we included adolescents aged 10–18 years with complete anthropometric and laboratory data for themselves and both parents. As LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald formula in KNHANES, which is not reliable when TG levels are ≥ 400 mg/dL, participants exceeding this threshold were excluded to ensure accuracy of lipid profile interpretation. A final total of 5,245 individuals were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Data collection

We collected anthropometric, clinical, and demographic data from the study population and their parents. Anthropometric data, including height, weight, waist circumference (WC), and body mass index (BMI), were converted into standard deviation scores (SDS). Clinical data included systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), serum glucose, total cholesterol (T-C), TG, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels. Patients who were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or dyslipidemia were included. We also collected demographic data such as alcohol consumption, smoking, physical activity, rural residency, and household income level.

Measurements in KNHANES

All measurements used in this study were based on standardized procedures conducted by trained personnel following the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency protocols for the KNHANES.

BP was measured three times on the right arm using a mercury sphygmomanometer (Baumanometer® Desk Model 0320; WA Baum Co., Inc., Copiague, NY, USA) after a resting period of at least 5 min in a sitting position. The average of the second and third measurements was used for analysis.

Anthropometric measurements, including height, weight, and WC, were performed by trained health technicians following standardized procedures. Height was measured using a stadiometer (Seca 225, Germany) to the nearest 0.1 cm, and weight was measured with a calibrated digital scale (GL-6000-20; G-tech, Korea) to the nearest 0.1 kg. WC was measured at the midpoint between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest using a non-stretchable measuring tape.

Blood samples were collected in the morning after an overnight fast of at least 8 h. All blood chemistry tests, including fasting glucose, T-C, TG, and HDL-C were analyzed at the central laboratory (Neodin Medical Institute, Seoul, Korea), which is certified by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. Serum samples were analyzed using the Hitachi Automatic Analyzer 7600 − 210 (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) with enzymatic methods, and external quality control was performed regularly through the Korean Association of External Quality Assessment Service.

Timing of data collection was synchronized for all participants in a given survey cycle. Parental and adolescent data were collected during the same year as part of the household sampling unit; thus, no time gap exists between parental MetS evaluation and offspring metabolic assessments.

Additional information on data collection methodology can be accessed via the official KNHANES website (https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr)22.

Definitions

Out of the several definitions of MetS used in children and adolescents, we adopted the NCEP-ATP III definition because of its emphasis on cardiometabolic risk. This definition is composed of five conditions, each analyzed in this study. First, elevated WC is defined as a WC that exceeds the 90th percentile based on sex, age, and race. Second, SBP or DBP above the 90th percentile for sex, age, and height was considered elevated BP. Third, a fasting blood glucose level of 110 mg/dL or higher was defined as elevated glucose. Fourth, elevated TG is indicated by a blood TG level of 110 mg/dL or higher. Finally, reduced HDL cholesterol is defined as a level of less than 40 mg/dL. Although HDL levels vary by sex and age, this fixed threshold has been widely adopted in large-scale epidemiological studies, including those using KNHANES23,24, due to its practicality and comparability. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is defined as meeting at least three out of the above five conditions. The NCEP approach allows for simplified risk stratification in populations where individualized reference values may not be feasible to apply.

Individuals who smoked five or more packs of cigarettes during their lifetime were defined as smokers, and those who consumed alcohol two or more times per month in a year were defined as alcohol drinkers. Physical activity was defined as meeting at least one of the following criteria: (1) vigorous exercise for 30 min or more, at least three times per week; (2) moderate exercise for 30 min or more, at least five times per week; or (3) walking for 30 min or more, at least five times per week. The household income was designated low if it fell below the first quartile. Participants in the lowest household income quartile were classified as having low socioeconomic status. All definitions for smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity were based on standardized KNHANES criteria.

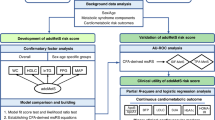

Statistical analysis

We used R version 4.4.2 for the statistical analyses. Basic descriptive statistics were computed for both continuous and categorical variables. These statistics included means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The subjects were divided into two groups: male and female adolescents. Comparisons between continuous variables were analyzed via Student’s t-test, whereas those between categorical variables were analyzed via the chi-square test. Subsequent comparative analyses were conducted between fathers of males and fathers of females and separately between mothers of males and mothers of females.

Comparative analyses were additionally conducted within the group of male adolescent offspring, examining differences based on the presence or absence of MetS in fathers and mothers, respectively. The same comparisons were performed within the female group. We used bar graphs to visualize the prevalence of MetS and its cardiometabolic components in female and male adolescents stratified by the presence or absence of paternal MetS. Similar bar graphs were created for the prevalence of these variables according to the presence or absence of maternal MetS.

To control for confounders and achieve stronger statistical power, we estimated adjusted mean values via analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). As above, the analysis was performed separately for males and females. The SDS values of WC and BMI were adjusted for the following covariates: age, alcohol consumption history, smoking history, rural residence, household income, and the age and BMI of the target parent. We employed the same set of covariates, with the addition of the target BMI SDS, to adjust for values of BP, glucose, T-C, TG, HDL-C, and LDL-C. To supplement statistical significance testing, we calculated effect sizes using Cohen’s d for continuous variables. A d ≥ 0.2 was interpreted as a small but clinically meaningful effect.

We used multiple logistic regression analysis to assess the effects of parental MetS status on MetS and cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescent offspring. The presence of MetS in the subject’s parent (paternal and/or maternal MetS) was designated as the independent variable. Elevated WC, elevated BP, elevated glucose, elevated TG, reduced HDL-C and MetS in targets were set as dependent variables to calculate the adjusted odds ratios (aORs) of each variable. The analyses were performed for each of three groups: all adolescents, male adolescents only, and female adolescents only. Common covariates included the target’s age, alcohol consumption history, smoking history, rural residence, household income, and age and BMI of the target’s parent. For analyses of elevated BP, elevated glucose, elevated TG, reduced HDL-C, and MetS, we included the target’s BMI SDS as an additional covariate. The target’s sex was adjusted for the analysis in all adolescent groups only.

To evaluate the potential impact of including multiple siblings from the same family, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. First, we compared the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components between single-child and multi-child families. Second, we performed a resampling analysis using one randomly selected child per family, repeated 1,000 times. Logistic regression was repeated in each iteration, and the stability of the results was assessed based on the proportion of p-values < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Baseline characteristics, including anthropometric, clinical, and demographic factors, of the study population and their parents are summarized in Table 1. Out of 5245 subjects, 2785 male adolescents and 2460 female adolescents were analyzed. Male adolescents were significantly taller and heavier and exhibited higher systolic and diastolic BP and serum glucose levels than female adolescents. Furthermore, male adolescents more frequently reported alcohol consumption and smoking and had higher physical activity levels. In contrast, female adolescents had higher T-C and LDL-C levels than male adolescents. No significant sex differences were observed in TG or HDL-C levels, household income, and prior diagnoses of metabolic conditions.

Among parents, fathers and mothers of the subjects were analyzed. Most demographic and clinical characteristics did not significantly differ between fathers or mothers of male and female adolescents. Minor differences were observed in age, WC, and physical activity among fathers, and in age, BMI, BP, TG levels, and hypertension diagnosis among mothers (Table 1).

Comparison of clinical characteristics by parental metabolic syndrome status

Comparisons of the clinical characteristics of the study population according to the presence of paternal and maternal MetS status are summarized in Table 2 and visualized in Figs. 2 and 3. In male adolescents, the presence of paternal MetS was associated with more adverse metabolic risk factors. Specifically, those with paternal MetS showed higher WC and BMI SDS, elevated systolic and diastolic BP, higher serum glucose, T-C, TG, and LDL-C levels, and lower HDL-C levels (Table 2). This significance is better visualized in Fig. 2, which shows an increased prevalence of elevated WC, BP, TG, reduced HDL-C, and overall MetS among male adolescents with paternal MetS, although the prevalence of elevated glucose was not significantly different.

Comparative bar plot of the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components based on the presence of paternal metabolic syndrome. The top row shows the prevalence of the male adolescents, while the bottom row represents the female adolescents. Dark blue bars indicate the absence of paternal MetS (“No”), whereas light blue bars indicate the presence (“Yes”).

Comparative bar plot of the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components based on the presence of maternal metabolic syndrome. The top row shows the prevalence of the male adolescents, while the bottom row represents the female adolescents. Dark blue bars indicate the absence of maternal MetS (“No”), whereas light blue bars indicate the presence (“Yes”).

Among female adolescents, the associations with paternal MetS were less pronounced. Higher BMI and WC SDS, increased BP, and lower HDL-C levels were observed, but no significant differences were found in glucose, T-C, TG, or LDL-C levels (Table 2). Reflecting this pattern, the prevalence of elevated WC, BP, TG, and overall MetS was greater in girls with paternal MetS, while no significant difference emerged for reduced HDL-C or elevated glucose (Fig. 2).

Maternal MetS also demonstrated consistent associations with adverse metabolic markers, particularly in male adolescents. Male adolescents with maternal MetS showed higher adiposity indices, increased BP, and significantly worsened lipid and glucose profiles. T-C, TG, and LDL-C levels were higher, HDL-C was lower, and fasting glucose was also significantly elevated (Table 2). Figure 3 supports these associations, showing increased prevalence of all MetS components except for elevated glucose, which did not differ significantly.

In female adolescents, maternal MetS was related to greater BMI and WC SDS, elevated BP, and increased serum levels of T-C, TG, and LDL-C, along with reduced HDL-C levels, while glucose did not differ (Table 2). Nevertheless, Fig. 3 reveals a significantly higher prevalence of elevated WC, TG, reduced HDL-C, and overall MetS in this group, although BP and glucose abnormalities remained comparable regardless of maternal MetS status.

Adjusted cardiometabolic risk profiles by parental metabolic syndrome status

After adjusting for covariates, the differences in cardiometabolic variables according to the parental MetS status are shown in Table 3, along with corresponding effect sizes (Cohen’s d). Among male adolescents with paternal MetS, TG levels (d = 0.231) and HDL-C levels (d = − 0.208) differed significantly with small but clinically meaningful effect sizes. Other variables including glucose, T-C, and LDL-C also showed statistical significance, but their effect sizes were below the clinical relevance threshold (d < 0.2). In female adolescents, paternal MetS was associated with elevated SBP, DBP, and TG, along with significantly reduced HDL-C levels; however, none of the corresponding effect sizes exceeded the clinical relevance threshold. Notably, the differences in WC and BMI SDS according to the presence of paternal MetS were not statistically significant in either sex.

In adolescents with maternal MetS, both male and female adolescents presented significantly higher levels of T-C, TG, and LDL-C, along with significantly lower levels of HDL-C. Among these, male adolescents showed not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful increases in SBP (d = 0.213), TG (d = 0.332), and a reduction in HDL-C (d = − 0.284). In contrast, although female adolescents also exhibited statistically significant changes in these lipid markers, the effect sizes for SBP and HDL-C were below the threshold of clinical significance, suggesting a more modest metabolic impact. Notably, TG levels were elevated in both sexes with maternal MetS, and the effect sizes in both groups (male: d = 0.332; female: d = 0.286) support the robustness of this finding from both statistical and clinical perspectives. Differences in BMI, SDS, and glucose levels according to maternal MetS status were not statistically significant in either sex.

Adjusted odds ratios for metabolic syndrome and its cardiometabolic components

The results of the multiple logistic regression analysis are summarized in Table 4, which presents the aORs of each cardiometabolic risk factor and MetS, stratified by offspring sex. In male adolescents with paternal MetS, significantly elevated aORs were observed for elevated BP, elevated TG, reduced HDL-C, and MetS. In contrast, female adolescents with paternal MetS demonstrated a more limited pattern, showing a significant increase only in the aOR for elevated BP. Although the aOR for MetS in females was elevated (1.66), it lacked statistical significance. Such results indicate a broad adverse impact on cardiometabolic risk in male adolescents and a weaker or more variable association in females. Notably, the aORs for elevated glucose were less than 1 in both sexes, although not statistically significant, suggesting a possible inverse relationship or a compensatory mechanism.

Similar to the findings in adolescents with paternal MetS, adolescents with maternal MetS presented significantly elevated aORs for elevated BP, elevated TG, reduced HDL-C, and MetS in male adolescents. In female adolescents, maternal MetS was significantly associated only with elevated TG, while other outcomes, including MetS itself, were not statistically significant. Results from maternal MetS also reflect a consistent pattern of increased risk in male adolescents and a more attenuated impact in female adolescents.

In order to introduce robustness of the study and account for potential sampling bias due to inclusion of multiple siblings from one family, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome components was not significantly different between single-child and multi-child families (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, repeated logistic regression analyses using one randomly selected child per family (1,000 iterations) demonstrated consistent statistical significance for key associations, particularly in male adolescents with paternal MetS (e.g., elevated TG, reduced HDL-C, and MetS; all with Proportion of P < 0.05 larger than 0.9) (Supplementary Table 2). These findings suggest that the inclusion of multiple siblings in the sample group did not introduce significant bias and alter the main results of this study.

Discussion

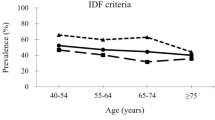

In this study, we analyzed the differential influence of paternal versus maternal MetS in their offspring MetS risk to provide a comprehensive understanding of inheritance patterns and elucidate the transmission of MetS risk across generations. For clarity on the definition of MetS in children, we defined MetS in adolescents using the modified NCEP-ATP III criteria, which are widely employed in pediatric research on MetS6,25. This approach allows flexible assessment of each component, such as dyslipidemia or hypertension, even in the absence of abdominal obesity. The IDF criteria, although internationally recognized, mandate central obesity and use fixed waist circumference thresholds, which may under-represent at-risk Korean adolescents26. Given these factors, the NCEP definition was deemed more suitable for our dataset and objectives.

The impact of paternal MetS is stronger than that of maternal MetS

Our findings suggest that paternal MetS have a greater impact on offspring BP and overall MetS risk, particularly in male adolescents. In our adjusted analysis, paternal MetS was associated with significantly higher levels of glucose, TG, LDL-C, and lower HDL-C in male adolescents. Among these, TG and HDL-C also demonstrated clinically meaningful effect sizes (Cohen’s d ≥ 0.2), supporting both statistical and clinical relevance of paternal influence. In contrast, while several variables in female adolescents reached statistical significance, most did not exceed the threshold of clinical relevance based on effect size.

Recently, the father’s lifestyle and metabolic status have been found to cause epigenetic changes in the sperm, which may regulate the gene expression of the child27. Additionally, negative paternal lifestyle factors, such as smoking and excessive sodium consumption, have been linked to hypertension in children28. Given that fathers are more likely to smoke and exhibit poorer dietary habits, as reported in previous studies, their lifestyle behaviors and/or epigenetic contributions may play a significant role in influencing their children’s metabolism, particularly BP regulation. In a direct sense, offspring BP and overall MetS risk could be attributable epigenetic inheritance via sperm; indirectly, shared lifestyle factors and broader environmental exposures may also contribute to this association. Although we included several lifestyle-related covariates in our models, residual confounding is possible, and future studies with more detailed behavioral data are warranted.

The transgenerational influence of mothers on children’s metabolic health has been broadly studied. Mothers’ nutrition during pregnancy, hyperglycemia, and obesity may alter DNA methylation patterns in their offspring, leading to detrimental metabolic health outcomes29. MEF2A hypermethylation30, altered noncoding RNA expression31, and activated mitochondrial metabolites32 are suggested to be specific mechanisms that affect lipid metabolism in children. Despite these findings, only a limited association between maternal MetS and female offspring was observed in our study, which may reflect underlying sex-specific protective mechanisms discussed below. Among the observed parameters, only TG levels in female offspring met both statistical and clinical significance.

Sex-specific mechanisms underlying cardiometabolic risk factors

Compared with male adolescents, female adolescents appeared to be less impacted by parental MetS in our study. This sex difference may be partially explained by the biological role of estrogen, which is known to regulate lipid metabolism and provide protection against cardiometabolic dysfunction33. As girls progress through puberty and experience an increase in estrogen levels, it can be hypothesized that the nearly adult level of estrogen in a portion of older adolescents may contribute to attenuating parental influences on their metabolic health. Notably, in Korea, the average onset of puberty has advanced in recent years, and the prevalence of precocious puberty is rising34,35. This implies that a substantial proportion of our female participants may have been hormonally mature despite the wide age range. However, given the retrospective nature of our study, we were unable to account for hormone levels in our analyses.

In addition to the protective role of estrogen, the female XX chromosome may further contribute to physiologic protection against epigenetic influences. Some genes, such as G6PD and KDM6A, are known to be involved in insulin resistance and lipid metabolism36,37. Even when X-linked genes are affected by parental epigenetic changes, females might benefit from a buffering effect through X-chromosome inactivation and genetic complementation38.

These findings highlight the importance of further research considering sex hormones and epigenetic changes to facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the sex-distinct inheritance patterns of MetS and to evaluate potential protective mechanisms in females. The pronounced susceptibility of male offspring and disparate patterns of parental influence between sexes highlight the need for a targeted approach to screening for metabolic diseases.

Sensitivity analysis excluding offspring with both parental MetS

We conducted additional analyses excluding offspring whose both parents were affected by MetS (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). After excluding these high-risk families39, the effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for cardiometabolic parameters decreased overall, suggesting that the presence of dual-affected parents may amplify the magnitude of parental influence. However, key associations remained directionally consistent: paternal MetS continued to show a stronger association with adverse cardiometabolic outcomes, particularly in male adolescents. Specifically, paternal MetS was associated with elevated BP, reduced HDL-C, and increased risk of MetS in male adolescents even after the exclusion of families with both parents affected (Supplementary Table 4).

Meanwhile, maternal MetS retained a significant association primarily with elevated TG in female offspring, but overall demonstrated a relatively smaller effect compared to paternal MetS. Although the magnitude of the paternal effect was modest and not uniformly superior across all outcomes, a pattern of relatively stronger paternal influence compared to maternal influence was still suggested. These finding support the robustness of our main conclusions regarding the sex-specific inheritance patterns of MetS.

The limited influence of parental MetS on abdominal obesity and glucose levels

In clinical settings, obese children tend to have obese parents40,41. However, our findings suggest that parental MetS has a weak association with central adiposity in offspring. This interpretation was supported by effect size estimates, where differences in WC SDS across groups failed to meet clinical significance thresholds despite sometimes reaching statistical significance. We utilized fasting blood glucose as a diagnostic marker according to the current definitions of pediatric MetS. However, fasting blood glucose, while practical and widely used, may not sufficiently reflect early insulin resistance, which is more directly influenced by parental MetS42.

Our study has several limitations due to its cross-sectional design and the lack of detailed data on dietary factors or hormonal profiles, which may have masked the potential parental influences on adiposity and glucose levels in subjects. In addition, important prenatal exposures such as maternal gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational age, and birth weight—which are well-documented to influence offspring cardiometabolic health—were not available in the KNHANES dataset. Future longitudinal studies should address these limitations by incorporating more comprehensive lifestyle, hormonal, perinatal and genetic data to better understand intergenerational transmission of metabolic risk.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we reaffirmed that parental MetS significantly impacts the general metabolic health of their offspring. Paternal MetS was shown to have an overall stronger influence on the offspring focused on BP and MetS, whereas lipid profiles had a stronger association with maternal MetS. The sex-specific effect was also evident in the offspring’s sex, with male adolescents demonstrating a more pronounced response to both parents’ MetS. In contrast, female adolescents provided limited responses. These results suggest that the inheritance mechanism of MetS is highly complex and that both parental and offspring sex should be considered in future screening and prevention of MetS.

Data availability

The data used in this study are from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, provided by the Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency. It is a publicly accessible database at https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/main.do, but it requires adherence to the policies of the Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

References

Bowo-Ngandji, A. et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in African populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 18, e0289155 (2023).

Ali, N., Samadder, M., Shourove, J. H., Taher, A. & Islam, F. Prevalence and factors associated with metabolic syndrome in university students and academic staff in Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 13, 19912 (2023).

Hirode, G. & Wong, R. J. Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the united States, 2011–2016. JAMA 323, 2526–2528 (2020).

Kim, M. J., Kim, M., Yoon, J. Y., Cheon, C. K. & Yoo, S. The impacts of COVID-19 on childhood obesity: Prevalence, contributing factors, and implications for management. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 29, 174–181 (2024).

Cannizzo, B. et al. Tempol attenuates atherosclerosis associated with metabolic syndrome via decreased vascular inflammation and NADPH-2 oxidase expression. Free Radic Res. 48, 526–533 (2014).

Kim, J. H. & Lim, J. S. The association between C-reactive protein, metabolic syndrome, and prediabetes in Korean children and adolescents. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 273–280 (2022).

Chiyanika, C. et al. The relationship between pancreas steatosis and the risk of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in Chinese adolescents with concurrent obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatr. Obes. 15, e12653 (2020).

Lucke-Wold, B. P. et al. Metabolic syndrome and its profound effect on prevalence of ischemic stroke. Am. Med. Stud. Res. J. 1, 29–38 (2014).

Reisinger, C., Nkeh-Chungag, B. N., Fredriksen, P. M. & Goswami, N. The prevalence of pediatric metabolic syndrome—a critical look on the discrepancies between definitions and its clinical importance. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 45, 12–24 (2021).

Druet, C., Ong, K. & Levy Marchal, C. Metabolic syndrome in children: comparison of the international diabetes federation 2007 consensus with an adapted National cholesterol education program definition in 300 overweight and obese French children. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 73, 181–186 (2010).

Rinaldi, R. et al. Gender differences in liver steatosis and fibrosis in overweight and obese patients with metabolic Dysfunction-Associated steatotic liver disease before and after 8 weeks of very Low-Calorie ketogenic diet. Nutrients 16, 1408 (2024).

Burt Solorzano, C. M. & McCartney, C. R. Obesity and the pubertal transition in girls and boys. Reproduction 140, 399–410 (2010).

Lepe, A., de Kroon, M. L. A., Reijneveld, S. A. & de Winter A. F. Socioeconomic inequalities in paediatric metabolic syndrome: Mediation by parental health literacy. Eur. J. Public. Health. 33, 179–183 (2023).

Biadgilign, S. et al. Association between dietary intake, eating behavior, and childhood obesity among children and adolescents in Ethiopia. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health. 6, 203–211 (2023).

Jackisch, J. et al. Does the effect of adolescent health behaviours on adult cardiometabolic health differ by socioeconomic background? Protocol for a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 14, e078428 (2024).

Wan, M. et al. Lifestyle intervention improves cardiometabolic profiles among children with metabolically healthy and metabolically unhealthy obesity. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 16, 268 (2024).

Corica, D. et al. Does family history of obesity, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases influence onset and severity of childhood obesity?? Front. Endocrinol. 9, (2018).

Ejtahed, H. S. et al. Association of parental obesity with cardiometabolic risk factors in their children: The CASPIAN-V study. PLOS ONE. 13, e0193978 (2018).

Martin, S. et al. Genetic evidence for different adiposity phenotypes and their opposing influences on ectopic fat and risk of cardiometabolic disease. Diabetes 70, 1843–1856 (2021).

Jääskeläinen, T. et al. Genetic predisposition to obesity and lifestyle factors–the combined analyses of twenty-six known BMI- and fourteen known waist:hip ratio (WHR)-associated variants in the Finnish diabetes prevention study. Br. J. Nutr. 110, 1856–1865 (2013).

Song, K. et al. Parental metabolic syndrome and elevated liver transaminases are risk factors for offspring, even in children and adolescents with a normal body mass index. Front. Nutr. 10, 1166244 (2023).

Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), 2007–2020. (Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency). at https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/eng/intr/srvyOtln.do

Lee, J. et al. Temporal trends of the prevalence of abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome in Korean children and adolescents between 2007 and 2020. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 32, 170–178 (2023).

Margolis, K. L. et al. Lipid screening in children and adolescents in community practice: 2007 to 2010. Circulation: Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 7, 718–726 (2014).

Khang, A. R. et al. Sex differences in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components in hypopituitary patients: comparison with an age- and sex-matched nationwide control group. Pituitary 19, 573–581 (2016).

Rezaianzadeh, A., Namayandeh, S. M. & Sadr, S. M. National cholesterol education program adult treatment panel III versus international diabetic federation definition of metabolic syndrome, which one is associated with diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease?? Int. J. Prev. Med. 3, 552–558 (2012).

Soubry, A., Hoyo, C., Jirtle, R. L. & Murphy, S. K. A paternal environmental legacy: Evidence for epigenetic inheritance through the male germ line. Bioessays 36, 359–371 (2014).

Kanamori, K., Suzuki, T., Tatsuta, N. & Ota, C. Environments affect blood pressure in toddlers: The Japan environment and children’s study. Pediatr. Res. 95, 367–376 (2024).

Franzago, M. et al. From mother to child: epigenetic signatures of hyperglycemia and obesity during pregnancy. Nutrients 16, 3502 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Maternal high-fat diet orchestrates offspring hepatic cholesterol metabolism via MEF2A hypermethylation-mediated CYP7A1 suppression. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 29, 154 (2024).

Zeng, Y., Wu, Y., Zhang, Q. & Xiao, X. Non-coding RNAs: The link between maternal malnutrition and offspring metabolism. Front Nutr 9, (2022).

Smith, E. V. L. et al. Maternal Fructose intake causes developmental reprogramming of hepatic mitochondrial catalytic activity and lipid metabolism in weanling and young adult offspring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 999 (2022).

Krakowiak, J. et al. Metabolic syndrome, BMI, and polymorphism of Estrogen Receptor-α in Peri- and Post-Menopausal Polish women. Metabolites 12, 673 (2022).

Kang, S., Park, M. J., Kim, J. M., Yuk, J. S. & Kim, S. H. Ongoing increasing trends in central precocious puberty incidence among Korean boys and girls from 2008 to 2020. PLoS One. 18, e0283510 (2023).

Choi, K. H. & Park, S. C. An increasing tendency of precocious puberty among Korean children from the perspective of COVID-19 pandemic effect. Front. Pediatr. 10, 968511 (2022).

Park, J. et al. Overexpression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is associated with lipid dysregulation and insulin resistance in obesity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 5146–5157 (2005).

Ito, Y. et al. Comprehensive genetic profiling reveals frequent alterations of driver genes on the X chromosome in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 84, 2181–2201 (2024).

Migeon, B. R. Why females are mosaics, X-chromosome inactivation, and sex differences in disease. Gend. Med. 4, 97–105 (2007).

Park, J. H., Cho, M. H., Lee, H. S. & Shim, Y. S. No, either or both parents with metabolic syndrome: Comparative study of its impact on sons and daughters. Front. Endocrinol. 16, 1518212 (2025).

Yoo, E. G., Park, S. S., Oh, S. W., Nam, G. B. & Park, M. J. Strong Parent–Offspring association of metabolic syndrome in Korean families. Diabetes Care. 35, 293–295 (2012).

Yang, Z. et al. Relationship between parental overweight and obesity and childhood metabolic syndrome in their offspring: Result from a cross-sectional analysis of parent–offspring trios in China. BMJ Open. 10, e036332 (2020).

Pankow, J. S., Jacobs, D. R., Steinberger, J., Moran, A. & Sinaiko, A. R. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease risk factors in children of parents with the insulin resistance (metabolic) syndrome. Diabetes Care. 27, 775–780 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgments to declare.

Funding

The authors did not receive any financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article and declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Park, JH. and Shim, YS. were responsible for the conceptualization of the study. Park, JH. and Cho, MH. performed data curation. Shim, YS. conducted the formal analysis. Shim, YS. and Lee, HS. developed the methodology. Lee, HS. provided supervision throughout the project. The original draft of the manuscript was written by Park, JH. while the other authors contributed to the review and editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, JH., Cho, M.H., Shim, Y.S. et al. Differential impact of maternal and paternal metabolic syndrome on offspring’s cardiometabolic risk factors. Sci Rep 15, 17651 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02854-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02854-7