Abstract

Evidence on the relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke in American populations is limited. This study aimed to investigate the association between dietary zinc consumption and stroke prevalence among US adults. This cross-sectional study analyzed data from adults (≥ 18 years) who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2013 and 2020. Dietary zinc intake, stroke history, and other relevant factors were examined. Logistic regression models were used to assess the association between dietary zinc consumption and stroke risk, while restricted cubic splines (RCS) were applied to explore potential non-linear relationships. A total of 2642 adults from four NHANES cycles (2013–2020) were included in the analysis. In multivariate logistic regression, individuals in the second quartile of dietary zinc intake (Q2: 6.09–8.83 mg/day) had a significantly lower odds ratio (OR) for stroke (OR = 0.64, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.41–0.99, p = 0.044) compared with those in the lowest quartile (Q1: ≤6.08 mg/day). RCS analysis indicated an L-shaped relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke odds (p = 0.041). Threshold analysis revealed that for individuals consuming less than 8.82 mg of zinc daily, the OR for stroke was 0.858 (95% CI 0.74–0.99, p = 0.037). Our findings suggest an L-shaped association between dietary zinc intake and stroke prevalence in American adults, with higher zinc intake associated with lower odds of stroke within a specific intake range.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide and the third most common cause of disability, posing significant public health and socioeconomic challenges during treatment and post-stroke rehabilitation efforts1,2,3. The two primary types of stroke are ischemic stroke (IS) and hemorrhagic stroke (HS)4. Lifestyle modifications, particularly dietary changes and physical activity, are among the most effective strategies for preventing and reducing stroke risk5,6,7,8. Therefore, investigating the impact of specific nutrients on stroke risk may provide valuable insights into prevention and management strategies9,10. Recently, the role of dietary zinc intake in neurological diseases has drawn attention11,12,13.

Zinc is an essential trace mineral with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, playing a critical role in maintaining membrane stability, cellular metabolism, cell proliferation and transformation, immune responses, and oxidative stress regulation14,15,16,17. Zinc is also necessary for maintaining the typical physiological processes in humans. It plays a critical role as a cofactor for antioxidant enzymes. Zinc deficiency has been linked to several chronic conditions, such as seizures, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, hypertension, depression, and cardiovascular diseases (CVD)18,19,20,21. Studies have reported that stroke patients tend to have lower serum zinc levels than healthy individuals and that zinc supplementation may aid in neurological recovery following a stroke22,23,24,25. However, these studies primarily focused on serum levels in stroke patients rather than examining dietary zinc intake in the general population.

In this study, we conducted a large cross-sectional analysis using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data to evaluate the potential relationship between dietary zinc consumption and stroke prevalence. We hypothesized that individuals with a history of stroke would have lower dietary zinc intake compared to the general population.

Methods

Study population

The NHANES dataset includes several cross-sectional continuous, stratified probability surveys of noninstitutionalized Americans26. This database has been maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics, which served as the source of data for the evaluation of the dietary and physical health of Americans in this study27,28. Through visits to homes and mobile examination centers (MEC), the NHANES collected relevant data for tests, meetings, and questionnaires for the assessment of the nutrition and health aspects of the study population28. Individuals participating in four 2-year NHANES study cycles from 2013 to 2020 provided the data for use in the present research. The study participants were adults of age > 18 years who had completed an interview earlier. Those with incomplete information about stroke, variables, or dietary zinc intake were excluded from the study.

Each protocol employed in the National Health and Nutrition Examination System research was authorized by the National Center for Health Statistics’ ethical review committee. In addition, before participating in the NHANES, each participant provided written informed consent.

Assessment of stroke

Self-reports were utilized as a part of the NHANES questionnaire to determine what constituted a stroke. As described elsewhere, the Medical Condition Questionnaire (MCQ) was used to detect stroke29. Previous research employing NHANES data employed self-reported stroke, and the findings of several studies demonstrated the validity of the self-reported evaluation method30,31,32. The participants were deemed to have experienced stroke if they responded with a “yes” to the question, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had a stroke?”

Assessment of dietary zinc intake

Information on dietary zinc consumption was extracted from the NHANES nutrition investigation through 24-h dietary recalls. The NHANES dietary data includes zinc variables for the first and second 24-h recall. Therefore, we used the average zinc intake from the two 24-h recalls for the assessments. We also used the dietary supplement questionnaire to collect information about the intake of zinc from supplements. Although 24-h recalls are frequently used in dietary assessment, the intake on a single day is a poor estimator of long-term usual intake when compared with statistical modeling33. The zinc content of each daily consumable that was offered was added to determine each person’s daily zinc consumption. The comprehensive automated memory system meticulously created standardized questions and answer options specific to each food item. The Computer-Assisted Dietary Interview (CADI) System was used to accurately assess the nutritional content based on each person’s food and drink intake with reference to the Agriculture Department’s Automated Multiple Pass Method (AMPM)34,35. The national cancer institute (NCI) method was widely used for the estimation of routine dietary intake based on 24-h dietary intake data36. The zinc variables for the first and second 24-h recall, and the intake of zinc from supplements were used in this study. The dietary zinc intake levels were divided into quartiles (Q1–Q4) with values of ≤ 6.08 mg/day, 6.09–8.83 mg/day, 8.84–13.02 mg/day, and ≥ 13.03 mg/day.

Assessment of covariates

Age, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, education level, family income, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, energy consumption, coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesteremia, antihypertensive medications, preventive aspirin, and lipid-lowering medications were among the many potential covariates that were evaluated, according to the literature32,37. Mexican Americans, non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and other races were the categories for evaluated race and ethnicity. There were three categories for marital status: married, living with a partner, and living alone. Less than 9 years, 9–12 years, and > 12 years were the range for educational achievement. The poverty income ratio (PIR) divided the family income into three categories, according to the American government report, as follows: low (PIR < 1.3), medium (PIR > 1.3–3.5), and high (PIR > 3.5)38. To determine BMI, a standardized technique based on height and weight, was applied. The smoking status was classified as never smokers, current smokers, and former smokers based on the classifications from previous research39. Based on the questionnaire’s question about whether the doctor had previously been notified of the illness and drugs, the prior disease (i.e., hypertension, hypercholesteremia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, antihypertensive medications, preventative aspirin, and lipid-lowing medications) was determined.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.3 and Free Statistics version 1.92. Categorical data were presented as counts and frequencies, while continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SDs). The relationships between dietary zinc intake and stroke were assessed using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), calculated through multivariable logistic regression models. Zinc consumption in food was categorized into quartiles for comparison. Three multivariable logistic regression models were developed, as shown in Table 3: models 1, 2, and 3. Model 1 was adjusted for sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity, education level, and family income). Model 2 was adjusted for the same sociodemographic variables as Model 1, in addition to smoking status, BMI, and energy consumption. Model 3 was adjusted for all variables in Model 2, in addition to coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesteremia, antihypertensive drug use, preventive aspirin use, and lipid-lowing drug use. A restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was performed to assess potential non-linear associations, adjusted based on Model 3 variables. Additionally, sensitivity and stratified analyses were conducted across different subgroups to verify the robustness of the findings. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

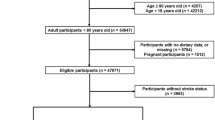

A total of 35,706 adults participated in the NHANES 2013–2020 surveys. After the inclusion criteria were applied, 13,908 participants under the age of 18 years old, 12,663 participants were excluded due to missing data on calorie intake, smoking, BMI, marital status, education, and family income, and 6853 participants were excluded due to incomplete data on hypertension, hypercholesteremia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, medication use (antihypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, preventive aspirin), dietary zinc intake, and stroke history. As a result, 2642 participants met the inclusion criteria for this cross-sectional study. A flowchart summarizing the inclusion process is presented in Fig. 1.

Participant characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the study participants, categorized by quartiles of dietary zinc intake. The study sample included 1438 women (53.7%), with a mean age of 62.8 years. Higher dietary zinc intake was associated with younger age groups, a larger proportion of men, non-Hispanic white ethnicity, married or cohabiting, higher educational attainment, middle-class family incomes, lower smoking rates, higher energy consumption, and higher BMI. Supplementary Table 1 provides a comparison of key characteristics between included and excluded participants.

Relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke

Univariate analysis identified significant associations between stroke and several factors, including age, non-Hispanic black ethnicity, marital status, higher family income, smoking history, BMI, hypercholesteremia, coronary heart disease, diabetes, medication use (antihypertensive drugs, preventive aspirin, and lipid-lowering drugs). Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

Multivariable analysis observed an inverse association between dietary zinc intake and stroke. After adjusting for potential confounders, participants in Q2 (6.09–8.83 mg/day) had a significantly lower odds of stroke (adjusted OR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.41–0.99, p = 0.044) compared to those in Q1 (≤ 6.08 mg/day) (Table 3). Furthermore, RCS analysis revealed an L-shaped relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke odds (p = 0.041), as illustrated in Fig. 2.

The analytical threshold analysis revealed that the OR for stroke prevalence was 0.858 (95% CI: 0.743–0.99, p = 0.037) for individuals consuming less than 8.82 mg by zinc per day. This suggests that for every additional 1 mg of dietary zinc intake per day, the odds of stroke are lower by 14.2% than before. However, when daily zinc intake reached ≥ 8.82 mg/day, no further correlation was observed between dietary zinc consumption and stroke odds (Table 4). This finding indicates that beyond a certain threshold, higher zinc intake through food is no longer associated with lower odds of stroke.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the impact of various factors (sex, age, marital status, education level, family income, and BMI) on the relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke. As shown in Table 5, no significant associations or interaction effects were found among these subgroups.

Discussion

This large-scale cross-sectional study of adult Americans revealed an L-shaped relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke prevalence. This inflection point analysis showed that when dietary zinc intake was less than 8.82 mg/day, stroke prevalence was lower with higher zinc intake. However, for individuals consuming ≥ 8.82 mg/day, the odds of stroke remained unchanged, even with higher zinc consumption. Subgroup analyses confirmed the robustness of this association. To our knowledge, this is the first cross-sectional study to examine the relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke in the NHANES database.

Research has suggested a link between zinc levels and stroke prevalence. In stroke patients with low zinc intake, restoring zinc levels to normal may improve neurological recovery23. A nested case-control study in hypertensive individuals found a significant inverse relationship between plasma zinc levels and the prevalence of first-time HS22. Similarly, patients with IS were found to have significantly lower blood zinc concentrations than healthy controls40. However, a meta-analysis of 12 case-control studies reported that elevated blood zinc levels might be associated with an increased prevalence of IS, while no significant association was observed between zinc levels and HS risk41. Interestingly, none of these studies assessed the relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke prevalence in the general population. Instead, most studies have focused on smaller sample sizes or shorter study durations. Our study, leveraging the NHANES dataset, provides a unique opportunity to examine the dose-response relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke, while adjusting for multiple confounding variables and conducting stratified analyses.

Our study found an L-shaped connection between the odds of stroke and between dietary zinc intake. Specifically, within a certain range, higher dietary zinc intake is associated with lower stroke prevalence. Individuals with lower zinc intake (< 8.82 mg/day) appear to benefit the most from increasing their dietary zinc consumption. However, for individuals consuming ≥ 8.82 mg/day, the prevalence of stroke does not decrease further with additional zinc intake. Currently, the recommended daily zinc intake is 11 mg for men and 8 mg for women, with higher requirements for pregnant women and children42. However, our study indicates that many adult Americans, particularly women, fail to meet their daily zinc intake requirements. Excessive zinc intake can lead to adverse effects, including headaches, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Prolonged high zinc consumption may interfere with the absorption and metabolism of essential trace elements, such as iron, copper, and calcium, potentially leading to iron-deficiency anemia, copper deficiency, and calcium deficiency, weakened immune function, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, and neurological complications.

According to the data, zinc plays a crucial role in both the pathophysiology and normal functioning of the brain43. However, the fundamental mechanisms linking zinc consumption to stroke remain unclear. Research suggests that zinc is associated with both IS and HS22,23. Zinc has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that protect vascular cells from free radical damage and inflammatory injury. Additionally, it plays a role in regulating cytokine production44. Atherosclerosis, the primary cause of CVD, including peripheral artery disease and stroke, is influenced by zinc through its interactions with immune cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells45. Zinc is essential for the activation and transformation of monocytes into macrophages, the formation of foam cells via oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) uptake in atherosclerosis, monocyte-endothelial adhesion, and diapedesis16. Clinical trials have shown that zinc supplementation can lower serum LDL cholesterol levels, regulate blood glucose levels, and reduce blood pressure44. Furthermore, zinc plays both beneficial and detrimental roles in blood pressure regulation, glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and other atherosclerosis-related risk factors20.

This study has several limitations. First, the dietary assessment relied on a 24-h recall method, which may have introduced recall bias, potentially affecting the accuracy of nutritional intake measurements. However, the 24-h recall method is considered more precise in capturing detailed information about food types and portion sizes compared to food frequency questionnaires46,47. Additionally, the CIs at the extreme ends in Fig. 2 are wide, indicating uncertainty in these regions. This is primarily due to challenges in study design and data collection, such as the small number of participants in these ranges, as well as external factors beyond our control. Furthermore, stroke diagnosis was based on self-reported data of participants, which may have led to misclassification or reporting bias. The survey also did not differentiate between HS and IS, limiting the specificity of our findings. Another limitation is the study population, which consisted solely of American adults, restricting the generalizability of the results to other ethnic or demographic groups. Additionally, we were unable to analyze specific populations due to the exclusion of individuals with incomplete data, potentially introducing selection bias. Despite using regression models and stratified analyses to control for confounding variables, residual unmeasured confounders may still be present. Finally, given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot establish a causal relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke prevalence. Further long-term studies, including randomized controlled trials, are necessary to confirm these findings.

Conclusions

Our study suggests an L-shaped relationship between dietary zinc intake and stroke presence in American adults. Within a specific range, higher dietary zinc consumption was associated with a lower odds of stroke. However, beyond a certain intake level, the protective effect plateaued. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to determine whether increasing dietary zinc intake can effectively reduce stroke prevalence.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic splines

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- Q:

-

Quartile

- IS:

-

Ischemic stroke

- HS:

-

Hemorrhagic stroke

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- MEC:

-

Mobile examination centers

- MCQ:

-

Medical condition questionnaire

- CADI:

-

Computer-assisted dietary interview

- AMPM:

-

Automated multiple pass method

- NCI:

-

National cancer institute

- PIR:

-

Poverty income ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

References

Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20, 795–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(21)00252-0 (2021).

Caldwell, M., Martinez, L., Foster, J. G., Sherling, D. & Hennekens, C. H. Prospects for the primary prevention of myocardial infarction and stroke. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 24, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074248418817344 (2019).

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 137, e67–e492. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000558 (2018).

Adams, H. P. Jr. et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. Toast. Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke 24, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.24.1.35 (1993).

Dybvik, J. S., Svendsen, M. & Aune, D. Vegetarian and vegan diets and the risk of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 62, 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-022-02942-8 (2023).

Chen, G. C. et al. Adherence to the mediterranean diet and risk of stroke and stroke subtypes. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34, 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00504-7 (2019).

Madsen, T. E. et al. Sex differences in physical activity and incident stroke: A systematic review. Clin. Ther. 44, 586–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2022.02.006 (2022).

Hung, S. H. et al. Pre-stroke physical activity and admission stroke severity: A systematic review. Int. J. Stroke 16, 1009–1018. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493021995271 (2021).

Spence, J. D. Nutrition and risk of stroke. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030647 (2019).

Jenkins, D. J. A. et al. Supplemental vitamins and minerals for cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment: Jacc focus seminar. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77, 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.619 (2021).

Wang, B., Fang, T. & Chen, H. Zinc and central nervous system disorders. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092140 (2023).

Mezzaroba, L., Alfieri, D. F., Colado Simão, A. N. & Vissoci Reiche, E. M. The role of zinc, copper, manganese and iron in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurotoxicology 74, 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2019.07.007 (2019).

Koh, J. Y. Zinc and disease of the brain. Mol. Neurobiol. 24, 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1385/mn:24:1-3:099 (2001).

Kim, B. & Lee, W. W. Regulatory role of zinc in immune cell signaling. Mol. Cells 44, 335–341. https://doi.org/10.14348/molcells.2021.0061 (2021).

John, E. et al. Zinc in innate and adaptive tumor immunity. J. Transl. Med. 8, 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-8-118 (2010).

Ozyildirim, S. & Baltaci, S. B. Cardiovascular diseases and zinc. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 201, 1615–1626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-022-03292-6 (2023).

Hall, A. G. & King, J. C. Zinc fortification: Current trends and strategies. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193895 (2022).

Doboszewska, U. et al. Zinc signaling and epilepsy. Pharmacol. Ther. 193, 156–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.08.013 (2019).

Li, Z., Liu, Y., Wei, R., Yong, V. W. & Xue, M. The important role of zinc in neurological diseases. Biomolecules https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13010028 (2022).

Shen, T., Zhao, Q., Luo, Y. & Wang, T. Investigating the role of zinc in atherosclerosis: A review. Biomolecules https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12101358 (2022).

Tamura, Y. The role of zinc homeostasis in the prevention of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 28, 1109–1122. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.RV17057 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Baseline plasma zinc and risk of first stroke in hypertensive patients: A nested case-control study. Stroke 50, 3255–3258. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.119.027003 (2019).

Aquilani, R. et al. Normalization of zinc intake enhances neurological retrieval of patients suffering from ischemic strokes. Nutr. Neurosci. 12, 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1179/147683009x423445 (2009).

Wen, Y. et al. Associations of multiple plasma metals with the risk of ischemic stroke: A case-control study. Environ. Int. 125, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.12.037 (2019).

Munshi, A. et al. Depletion of serum zinc in ischemic stroke patients. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 32, 433–436. https://doi.org/10.1358/mf.2010.32.6.1487084 (2010).

Zipf, G. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: Plan and operations, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat. 1, 1–37 (2013).

Juul, F., Parekh, N., Martinez-Steele, E., Monteiro, C. A. & Chang, V. W. Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 115, 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqab305 (2022).

Chen, T. C., Clark, J., Riddles, M. K., Mohadjer, L. K. & Fakhouri, T. H. I. National health and nutrition examination survey, 2015–2018: Sample design and estimation procedures. Vital Health Stat. 2, 1–35 (2020).

Mao, Y. et al. Association between dietary inflammatory index and stroke in the Us population: Evidence from Nhanes 1999–2018. BMC Public. Health 24, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17556-w (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Magnesium intake and all-cause mortality after stroke: A cohort study. Nutr. J. 22, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-023-00886-1 (2023).

Dong, W. & Yang, Z. Association of dietary fiber intake with myocardial infarction and stroke events in US adults: A cross-sectional study of Nhanes 2011–2018. Front. Nutr. 9, 936926. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.936926 (2022).

Yang, L., Chen, X., Cheng, H. & Zhang, L. Dietary copper intake and risk of stroke in adults: A case-control study based on national health and nutrition examination survey 2013–2018. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030409 (2022).

Dodd, K. W. et al. Statistical methods for estimating usual intake of nutrients and foods: A review of the theory. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 106, 1640–1650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2006.07.011 (2006).

Stote, K. S., Radecki, S. V., Moshfegh, A. J., Ingwersen, L. A. & Baer, D. J. The number of 24 h dietary recalls using the US department of agriculture’s automated multiple-pass method required to estimate nutrient intake in overweight and obese adults. Public. Health Nutr. 14, 1736–1742. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980011000358 (2011).

Rhodes, D. G. et al. The Usda automated multiple-pass method accurately assesses population sodium intakes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97, 958–964. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.044982 (2013).

National cancer institute. The healthy eating index: Sas code. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/sas-code.Html

Shi, W. et al. Correlation between dietary selenium intake and stroke in the national health and nutrition examination survey 2003–2018. Ann. Med. 54, 1395–1402. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2058079 (2022).

Liu, H., Wang, L., Chen, C., Dong, Z. & Yu, S. Association between dietary niacin intake and migraine among American adults: National health and nutrition examination survey. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153052 (2022).

Liu, H., Wang, Q., Dong, Z. & Yu, S. Dietary zinc intake and migraine in adults: A cross-sectional analysis of the National health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2004. Headache 63, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14431 (2023).

Mirończuk, A. et al. Selenium, copper, zinc concentrations and Cu/Zn, Cu/se molar ratios in the serum of patients with acute ischemic stroke in Northeastern Poland-a new insight into stroke pathophysiology. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072139 (2021).

Huang, M. et al. Serum/plasma zinc is apparently increased in ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 200, 615–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-021-02703-4 (2022).

Kesari, A. & Noel, J. Y. Nutritional Assessment (StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2024).

Takeda, A., Fujii, H., Minamino, T. & Tamano, H. Intracellular Zn(2+) signaling in cognition. J. Neurosci. Res. 92, 819–824. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.23385 (2014).

Olechnowicz, J., Tinkov, A., Skalny, A. & Suliburska, J. Zinc status is associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, lipid, and glucose metabolism. J. Physiol. Sci. 68, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-017-0571-7 (2018).

Hara, T., Yoshigai, E., Ohashi, T. & Fukada, T. Zinc in cardiovascular functions and diseases: Epidemiology and molecular mechanisms for therapeutic development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087152 (2023).

Prentice, R. L. et al. Evaluation and comparison of food records, recalls, and frequencies for energy and protein assessment by using recovery biomarkers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 174, 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr140 (2011).

Park, Y. et al. Comparison of self-reported dietary intakes from the automated self-administered 24-h recall, 4-d food records, and food-frequency questionnaires against recovery biomarkers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 107, 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx002 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the reviewers who participated in the review and MJEditor (www.mjeditor.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81701271, 82371304), Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No.242300420071) and China Association against Epilepsy Foundation (No.UCB-2023-056).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data curation, XKW; Methodology, XKW and MMS; Funding acquisition, SKF and HFZ; Supervision, HFZ and SKF; Writing-original draft and review & editing, XKW, MMS, HFZ and SKF. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study method was approved by the NHANES Institutional Ethics Review Committee, with all NHANES participants provided signed informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors give the consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Shi, M., Zhang, H. et al. Dietary zinc intake associated with stroke in American adults. Sci Rep 15, 18301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03122-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03122-4