Abstract

Streamflow contemplates a fundamental criterion to evaluate the impact of human activities and climate changes on the hydrological cycle. In this study, a novel innovative deep neural network (DNN) structure by integrating a double Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) neural network model with a multiplication layer and meta-heuristic whale optimization algorithm (WOA) (i.e., hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model) is developed to improve the prediction accuracy and performance of mean monthly Chehel-Chai River’s streamflow (CCRSFm) in Iran. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) and Cosine Amplitude Sensitivity (CAS) as feature (input) selection process determine the only precipitation (Pm) as the most effective input variable among a list of on-site potential climate time series parameters recorded in the study area. Thanks to a well-proportioned layer network structural framework in the suggested hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model, it leads to an appropriate total learnable parameter (TLP) compared to standard individual GRU and Bi-GRU as the benchmark models developed in the comparable meta-parameters. This hybrid model under the optimal meant meta-parameters tuned i.e., coupling a state activation functions (SAF) of tanh-softsign, dropout rate (P-rate) of 0.5, numbers of hidden neurons (NHN) of 70, outperforms with an R2 of 0.79, NSE of 0.76, MAE of 0.21 (m3/s), MBE of -0.11(m3/s), and RMSE of 0.36 (m3/s). Hybridizing the 2GRU× model with WOA algorithm causes to increase in the value of R2 by 6.8% and reduce in the value of RMSE by 20.4%. Comparatively, standard individual GRU and Bi-GRU models result in an R2 of 0.59 and 0.66, NSE of 0.55 and 0.6, MAE of 0.91 and 0.53 (m3/s), MBE of 0.047 and − 0.06 (m3/s), RMSE of 1.29 and 0.83 (m3/s), respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and literature review

During recent eras, due to quick populace growth, industrialization, urbanization, and increasing civic water demands, providing water is a crucial undertaking for lawmaking1,2,3. It necessitates a strong evaluation of available and future water supplies and the influences of climate and environmental changes on socio-hydrologic systems4. Devotion to this anxiety has been amplified lately because of water crises.

Climate changes and anthropogenic doings have brought on a perceptible intensification in periodic surface hydrologic extreme occasions such as an increase in frequency and intensity of universal temperature, rainfall, streamflow, droughts, and floods in the world in the twenty-first century5,6.

In the prior eras, hydrologists made many investigations to reply to the next question “What occurs to precipitations?”. Streamflow has been regularly pondered as an inclusive response factor to evaluate watershed climatology, hydrology, and other catchment features. Precise spatiotemporal streamflow forecasting as a periodic feature of the atmospheric hydro-meteorological factors are very central matters for hydrologists in the water-related sectors such as regional cascade planning and managing of water resources, irrigation, municipal sustainable development, hydropower generation systems, optimum reservoir operation, agricultural planning, flooding control and risk scrutiny; social security and catastrophe hindrance7,8,9.

Streamflow forecasting for the long lead time is still a challenging mission as analyzing the river manners for operative objectives. For these purposes, hydrological modeling methods (HMMs) as the recognized worthy framework have been extensively utilized since the mid-1970s to scrutinize, comprehend, and forecast several complex natural procedures of periodic hydrology applications, for instance, streamflow10,11. In a wider perspective, HMMs dependent on offering solutions at diverse levels of computational intricacy are categorized into two chief kinds: (I) Process-Driven and (II) Data-Driven techniques3,12.

Adopting process-driven models for hydrological phases entails sophisticated intellectual mathematical formulas and a substantial quantity of geographical multi-source calibration data to assure a satisfactory rate of model exactness13,14. Accordingly, hydrologists have to exploit the data-driven models as an appropriate substitute to assess the intricate hydrological process. Data-driven models by applying artificial intelligence (AI) techniques try to attain a potential relation among various multidimensional dynamics predictors–target dynamics variables with exceptionally complex unbalanced trends without any previous hypothesis or information on the fundamental physical latent features and relationships among them in estimation catchments15,16. These flexible and robust approaches have been developed to obviate the troubles of numerical tactics application, costly and timewasting process of large-scale atmospheric hydro-meteorological data records in monitoring and assessing various periodic hydrological parameters in different complex geo-spatiotemporal environments and climatic regimes17. These techniques have shown admirable competence in assessing multivariate spatiotemporal byzantine and nonlinear univariate time series hydrological events and hydraulic variables in complex environs and climate change such as modeling the periodic groundwater level variations18, daily air temperature19, reservoir inflows discharge20, discharge coefficient of diverse weirs21,22, dimensions of flow separation zone23, drought forecasting24.

As far as this, to predict streamflow in different environs and hydro-climatic conditions, abundant water science engineers have developed diverse kinds of traditional single data-mining models e.g. Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Genetic Programming, and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS)25,26,27, Non-Linear Autoregressive Moving Average with Exogenous Input Polynomial model28, Autoregressive-Moving Average, Autoregressive (AR) Moving, and Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS) models29,30,31, Gaussian Process Regression model32,33, Functional Linear models34, Regression Tree models35, Online Sequential Extreme Learning Machine models36,37,38, and ensemble and stochastic conceptual data-driven methods39, Empirical Random Forest Family’s model40, Bayesian Model Averaging41, Support Vector Regression (SVR) model42,43,44. Soo et al. compared the ability of five machine learning models (MLMs), including K-Nearest Neighbors, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), ANN, and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) in forecasting in Klang River Basin, Malaysia45. They announced that within the methods used, RF − III presented superior performance with Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error and Median absolute percentage error amounts of 0.36 and 0.37, respectively.

Of data-driven models, Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) neural network was presented by Cho et al. as a reformed kind of LSTM, the most popular version of deep neural networks (DDNs)46. It can effectively satisfy the innate gradient vanishing problem in the usual neural networks and the temporal data using pertinent interior gates47,48. GRU is contemplated as the leading approach with noteworthy advancement in real-time forecasting of the geological nonlinear rainfall-runoff time series process more effectively with delay times of more than a few months of the watershed. Generally, DDNs can accomplish higher forecasting precision than physical process-based approaches in most situations as they are able to analyze deeper structures and mine high-dimensional data. They have been utilized to assess streamflow process in different watersheds by the majority of researchers49,50,51.

The multivariate complex time series hydrological variables particularly streamflow, consist of naturally both perpetual stochastic and deterministic elements. Hence, an unimpeachable real-time appraisal contemplates a strenuous and time-consuming concern as a consequence of their extreme long-term non-stationarities and uncertainties latent in the spatiotemporal input-target data, randomization, human interventions, and highly indeterminate nonlinear characteristic accompanied by multipart interactions/forms within atmospheric elements52,53. For these reasons, the applicability of the traditionally used individual regression-based and data-mining tools is almost ineffectual and has generally bumped into serious predicaments such as high spatial-temporal fluctuations depending on severe uncertainties, nature resolutions, weights fit-tuning, etc54,55,56.

Taking all the together, to impede the all above-mentioned difficulties and interludes, different strong and leading-edge hybrid signal pre-processing (mode decomposition) and bio-inspired optimization-based data-mining models for large-scale data analytical as an appropriate alternative are being developed to improve noticeably predictions’ talent and efficiency of ordinary models. The hybrid strategies employ the incorporation of two or further data integration and modelling modus operandi prompting feasible to prominently increase the exactness of forecasted streamflow data.

The nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization-based algorithms bring forth improve the ability of standalone predictive models by incorporating different optimization algorithms by realizing close-optimum results within a rational timeframe for the estimation parameter, while concurrently could diminish the computational convergence time period57. Outdated customary optimization algorithms have limitations including single-based solutions, complications in indefinite search spaces, and converging to local optima15,16,58. To date, numerous investigators have designed metaheuristic algorithms to address these limitations. On this point, the whale optimization algorithm (WOA) presented by Mirjalili & Lewis is a robust and reliable bio-inspired metaheuristic optimization algorithm motivated by the intelligence and social life manners of humpback whales59. This algorithm is characterized by the bubble-net hunting tactic and is applicable in global optimization machine learning and data mining problems by imitating physical or biological phenomena.

Hitherto, different hybrid algorithms have been developed by adjusting and optimizing the simulation factors and broader choice of the membership function to enhance the accuracy of predicting streamflow in different regions and hydro-climatic conditions. For example, different hybrid meta-heuristic optimization-based algorithms including the Shuffled Frog Leaping, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization, Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO) algorithms60, hybrid Genetic Algorithm with SVR and Bayesian Additive Regression Tree models61, hybrid Improved Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise algorithm and GRU model with improved GWO algorithm62, hybrid Gravitational Search, PSO and GWO optimization algorithms with the extreme learning machine (ELM) model63, hybrid optimally pruned ELM (OP-ELM), least square support vector machine, seasonal auto regressive moving average, MARS, and M5 model tree64, hybrid SVR and generalized regression neural network models with seasonal and trend decomposition algorithms65, hybrid fuzzy information granulation with SVR model66. A summary of the different hybrid models developed for predicting streamflow in different areas is presented in Table 1.

Motivation for this study

This research intends to estimate a long-term time series of mean monthly Chehel-Chai River’s streamflow (CCRSFm) using climatic datasets from Sep 1990 to Aug 2020 by GRU deep learning, MLMs. To do so, first of all, the general single GRU layer network as the benchmark model, the general single Bi-directional GRU (Bi-GRU) layer network, and the double GRU coupled with a multiplication layer (i.e., 2GRU× model) network models are developed. Then, the ideal one of these initially designed meant models (based on performance evaluation metrics calculated) is intentionally hybridized with meta-heuristic whale optimization algorithm (WOA) (i.e., hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model) to further improve the prediction accuracy of CCRSFm. Therefore, we do not limit our investigation only to the conventional deep learning (DL) network structure. Since the WOA algorithm mostly presents a steady and fast convergence rate and can identify optimum solutions in lower populations with the lesser opportunity of local trapping modes, it is used as nature-inspired optimization algorithm.

As the aptitude of these models relies on the kind and rate of some meta-parameters, realizing a fitting optimum pattern is a demanding and bewildering undertaking. Hence, various scenarios are adopted by tuning diverse meta-parameters in the construction of suggested models and the WOA algorithm.

The literature review shows that there has been little research operating different layer structures of the GRU model for time series streamflow forecasting. As far as authors know, amongst the current computational intelligence-system literature centering on streamflow prediction, only commonplace and wide-ranging simple DNN architectural structures have been focused on. The novelty of this research is the development of a leading-edge and robust, unique hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model with different analytical layer network structures, for the first time to predict more complex natural phenomena such as time series CCRSFm oscillations patterns.

Study area and data description

Chehel-Chai River is one of the main branches of Gorganrood River and is located in Golestan Province, northern Iran. The Chehel-Chai watershed is situated inside the city border of Minoodasht with an area of 256,830 (m2), a mean slope of 46%, a maximum and minimum elevation of 2570 and 190 m above sea level, and a moist environment. The mean yearly precipitation and temperature were reported as 750 mm and 15.4 (°C), respectively. Forest (60%) and rain-fed lands (39%) shape the chief surrounding ground cover in this area76,77. Figure 1 shows Golestan Province and the location of the observation station generated using QGIS 3.40.

In the current study, to forecast time series mean monthly Chehel-Chai River’s streamflow (CCRSFm) (m3/s), 360 monthly atmospheric datasets documented from Sep 1990 to Aug 2020 by Lazoreh climatic observation station are exploited. The historic climatic parameters operated include monthly mean, maximum, minimum, absolute minimum, and absolute maximum air temperature (Tave, Tmax,Tmin,Tmina,Tmaxa), precipitation (Pm), evapotranspiration (ETm) gotten from the IMO (Iran Meteorological Organization). Table 2 provides some descriptive statistics indices of the variables used in the study area and period.

Research objectives

The main contributions of the present work are as follows:

-

1.

Identify the most effective variables on CCRSFm, among a list of on-site potential climate parameters recorded through feature selection techniques.

-

2.

Development of standalone and hybrid GRU-based neuro-evolution time series paradigms optimized by WOA nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for precise forecasting of CCRSFm vacillations rhythm.

-

3.

Determine the optimal spectrum of aimed meta-parameters in GRU-based models developed and WOA optimization algorithm for better configuration and lessening the impact of overfitting/underfitting problems.

-

4.

Assess and compare the accuracy of modeling with counterparts in the validation stage to differentiate the attributes of the best-developed model in offering better reliable and consistent performance using some comparison plots and statistical metrics.

Feature selection process

Because the performance of any modeling is influenced mainly by an apt selection of input variables for the precise prediction of target, unfit selections could adversely affect the effectiveness of any methodology. So, in this section, existing large-dimensional potential hydro-climatic data sets recorded in the studied region are evaluated to recognize the most effective input variables for predicting CCRSFm as the model target variable. In this context, the variables of extreme importance are selected using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) and Cosine Amplitude Sensitivity (CAS) as linear and nonlinear representative data analysis methods.

The CAS data inquiry for the variables presented in Table 3 is done by altering each input variable at a fix ratio and holding the other input variables constant as follows78:

where, Ii and Oj are input and output parameters, respectively, and n is total number of datasets. The Rij value [0,1] shows the strength of the relationship within the input and target parameters. The values of PCC and CAS methods are presented in Table 3.

According to Table 3, as a result of the insignificant amount of PCC and CAS data analysis methods for Tmin, Tmax, Tave, Tmina, Tmaxa, ETm, their effects on predicting CCRSFm by suggested models can be disregarded. Hence, merely Pm can be considered as the most influential and important input parameter. To conclude, the equation for the prediction of CCRSFm can be formulated as follows:

Figure 2 (A and B) shows the time series plots of CCRSFm and Pm recorded by Lazoreh climatic observation station for the studied time that show the seasonality of data. Since the parameters have a temporal pattern, the monthly scale is used as a parameter.

Time series graphs of variables used in Eq. 2 between Sep 1990-Aug 2020 (360 months) in the Chehel-Chai River watershed: (A) CCRSFm, (B) Precipitation (Pm).

Methodology

Due to the unstable, intricate, and nonlinear relationship in Eq. 2, only precise and robust approaches are enabled to analyze CCRSFm. In this context, a sequential dataset of 360 monthly hydro-climatic observations covering the period from September 1990 to August 2020 is used in modeling process. The datasets are normalized to zero mean and unit variance as advised by Lawrence et al.79. The normalized datasets are divided into two subclasses. One limited 70% of the data (252 monthly observations) are consecutively applied in calibrating the predictive models. And, the lasting 30% (108 samples) are set aside to be applied serially in validation, without randomization. This process warranted that the data be on a uniform scale, so discrete variable sensitivity did not complicate the results.

GRU and Bi-GRU neural networks

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) assimilate previous info to cross for forecasting the future state of a variable using input data with certain dependencies by enforcing a memory cell containing an unfolded loop cell. However, for large-scale data, its learning process meets with disappearing gradients in the backpropagation training algorithm over time80. To overcome this problem, LSTM adds intentionally hidden units to the memory cell of RNNs, so that it maintains information over long periods thanks to its unparalleled progressive structure named, Credit Assignment Paths (CAPs)80,81,82,83.

GRU neural network is capable of learning long-term relationships and assessing highly nonlinear historical information if the data scale is not too vast. Both GRU and LSTM neural network models act in an alike way with an analogous central framework. GRU is an adaptive neural network since it is quicker in computing, simpler in learning, less condensed in construction, and has fewer learnable factors with a distinguished inherent proficiency84,85. Figure 3 illustrates the working order of the system and the interior memory cell of GRU, where rt, xt, and ht are the reset gate of GRU, input variable, and hidden state at time t, respectively. Wr and Ur denote weight matrices for the input data and hidden state, respectively.

Against LSTM, GRU does not include isolated memory cells, as a substitute, it employs a separate ht to dispense data over time steps. Furthermore, the input and forget gates are incorporated with an update gate (z), and rt is straightly applied to ht−1 to obtain ht (the candidate state). In this system, the memory cell learns at time t by the input at time t and the output at the prior time step (t-1). The instruction of GRU is defined by the subsequent computations46:

In these equations, tanh and σ are the hyperbolic tangent and logistic sigmoid functions, respectively. The sign “×” and b denotes the element-wise multiplication and bias vector, respectively. These factors are learnable sets. Attributable to the impact of σ, whole gates are a vector within (0, 1). When the rt is locked, GRU is influenced just by xt and zt controls the information dimension of ht−1 can be passed into ht46.

The GRU model only considers the effect of the prior information on the succeeding information without regarding the correlation sides in time series predicting86. The Bi-GRU network model with several gates in the memory cells is based on different forms of the general one-directional GRU; nonetheless, reiterating elements within the hidden layer are more intricate. It includes forward and backward GRU to manage the input-output current inside the network and extract features in-depth by forward and reverse historic sequence computations87,88. The model construction is displayed in Fig. 4. Last of all, the output is calculated by the following formulation86:

where, \(\overrightarrow {{h_t}} ~and\) \(\overleftarrow {{h_t}}\) are the outputs of the forward and backward GRU, respectively.

Whale optimization algorithm (WOA)

Whales are considered the largest mammals with strong intellectual and emotional abilities, like humans, in the world. The whales lived habitually in groups, and the humpback whales have an exceptional hunting technique known as the bubble-net feeding technique. It enforces functional twisting movements to make a bubble-net raiding mechanism called bubble-net feeding. These bubbles are called double-loops and upward spirals. Humpback whales wish to forage for small fish or krill schools near the sea’s surface. It has been perceived that this hunting mode is done by forming typical bubbles sideways a loop or ‘9’-shaped track as exposed in Fig. 559,89,90.

Bubble-net nourishing method of humpback whales59.

The WOA was presented by Mirjalili & Lewis59 and is considered a well-known swarm intelligence algorithm inspired by the real special chasing tactics of humpback whales in nature, done by the unsystematic or finest search agent to hunt the prey. It is executed in three stages: (i) Siege chasing; (ii) Operation stage: The process of raiding the net bubble; (iii) Exploration stage: Chasing search. Some unsystematic solutions initiated WOA. In each reiteration, the search agents bring their situation up to date by the three operators. The WOA supposes that the optimum solution at the moment (the optimum response) is prey; so, it identifies prey and then encircles prey. When the agent of the optimum search is recognized, other search agents inform their place to the optimum search agent59. The following formulas can describe this process:

where, t signifies the present repetition, \(\vec {A}\) and \(\vec {C}\) are the coefficient vectors, X* is the position vector of the optimum solution attained at present, and \(\vec {X}\) is the position vector. \(\vec {D}\) also displays the space amid the hunt and ith whale. The vectors \(\vec {A}\) and \(\vec {C}\) are computed as follows:

where, \(\vec {a}\) is linearly reduced from 2 to 0 over the progress of repetitions (in both exploration and exploitation stages) and \(\vec {r}~\)is a random vector in [0,1].

The bubble-net invading method contains two chief stages: (i) the encirclement process which whales drive to the water surface) denotes shrinking and includes decreasing \(\vec {a}\) in the Eq. (10). The quantity of \(\vec {A}\) reduces as \(\vec {a}\) declines; and (ii) spiral updating of the whales’ locations is utilized to mimic the spiral activities of whales in the hunt boundary by computing the distance amid the hunt (X*, Y*) and the hunter (X, Y)59:

\(\overrightarrow {D^{\prime}}\)= |\({\vec {X}^*}\left( t \right) - \vec {X}\left( t \right)|\) describes the distance amid the ith whale and the hunt; b shows a coefficient defining the form of the logarithmic helix-formed movements; l shows a random quantity in [− 1,1]. The movement of the whales near the prey happens alongside the spiral-formed routes by wincing the loops. The following equation is presented to describe this process59:

where, p ∈ [0,1]; this permits one to catch the likelihood of retaining the spin mode so as to bring up-to-date the positions of the whales. In the exploration (searching) stage, the humpback whales’ quest for the prey is arbitrarily consistent with their position as matched to other whales59. Thus, the whales bring their situations up-to-date, compliant with randomly chosen search factors instead of the premium search factor59:

where, \(\overrightarrow {{X_{rand}}}\) is a random site detected by the present population. Figure 6 offers pseudo-code of the WOA algorithm.

Model development

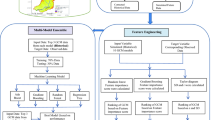

As mentioned above, in this study, first, the general single GRU and Bi-GRU neural networks are used as benchmark models for performance comparison, and then a 2GRU× neural network model with sequence output mode is developed to estimate CCRSFm in the study area. Figure 7A–C portrays the GRU-based layer network structure of models.

Finally, due to the smallest RMSE and highest R2 values in Model 3 compared to Models 1 and 2, it is preferred to hybridize with the WOA algorithm (i.e., hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model (4)) to improve the prediction accuracy of CCRSFm further. In this model, WOA trained the bias and weights within layers of the 2GRU× model so that they could be updated in keeping with a proportion recognized by the premium WOA. Then, the training set is applied to the renovated bias and weights of the 2GRU× model, and the WOA optimizes them in each repetition by randomly dispensing mode. This hybrid model terminates as a maximum number of iterations are gotten or as the best solution is obtained for a certain number of iterations; if not, it proceeds with the next generation operation.

The capability and computation complexity of the hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model generally relies on using the suitable main deterministic factors of the WOA algorithm, including population size (PS), maximum number of iterations, total load demand, up-coefficient vector, and down-coefficient vector. Selecting the optimal factors of bio-inspired WOA algorithm is very imperative so that the optimal key deterministic parameters and pattern for 2GRU× model be achieved using the optimization process. Figure 8 defines the forecasting process of the hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model.

In these models, the amount of P-rate and the kind of SAF as meta-parameters are exactly tuned to realize a proper pattern and augment the skill of the models designed. Nonetheless, since there is no formal pre-instruction to identify suitable meta-parameters for DDN models with a given dataset, this process is pondered as a time-wasting and demanding task18. For the sake of this aim, several scenarios are adopted to realize valid values.

In all models, the Input layer feeds the time series Pm into the layers’ network structure. For a useful configuration and modification in the big dataset, the Dropout layer is operated to deter overfitting by passing over some hidden neurons with a prearranged option rate of P91. To tune the amount of P-rate as a meta-parameter, various values are tested. To strengthen fitting ability in learning long-term sequential datasets, the Fully Connected layer is utilized with input and output sizes of “auto” and 1, respectively. The Multiplication layer multiplies the inputs from various layers’ neural network element-wise. As the ending layer, the Regression Output layer is utilized to compute the “half-mean-squared-error loss” for regression objectives. To tune SAF, a diverse combination of tanh and softsign are distinctly utilized, and for NHU, numerous amounts are tested. In order to preclude the gradients disappearing and lessen the negative influence of padding drawbacks, a training process with 1000 maximum repetitions is set as recommended by Lin et al.18. More details about the function of layers in the all models developed were provided by92.

Performance evaluation metrics

In this modelling, the following statistical metrics are applied to liken the capability and performance of all models used in predicting the time series CCRSFm:

where N is the number of datasets, \({P_i}\) and \({O_i}\) are the predicted and observed CCRSFm at time i, \({\sigma _o}\) and \({\sigma _P}\) are standard deviations of the observed and predicted the CCRSFm. The \({\mu _p}\) and \({\mu _o}\) are the mean predicted and observed CCRSFm. The best amount for Eqs. (16–20) are 1, 0, 0, 1, and 0, respectively.

Results and discussion

Validation of the models

In this simulation, numerous experiments are conducted to determine the optimal value of the main deterministic factors in the models developed. The characteristics and statistical results of all models used under the optimal scenario in the validation phase in forecasting CCRSFm are shown in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. The models in their training stages are more precise than in their testing stages. The tanh-softsign pairing in the hidden layers of the 2GRU× and hybrid 2GRU×–WOA models brings forth learning more complicated nonlinear functions, and accordingly, it causes the models not to be as much open to the overfitting dilemma. Besides, the ideal amount of main deterministic factors for WOA algorithm in the hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model for the best solution in forecasting CCRSFm is achieved as an up-coefficient vector of 0.25, a down-coefficient vector of 0.1, a total load demand of 0.05, a maximum number of iterations of 500 and a population size of 30.

According to Table 5, it can be concluded that hybridizing with the WOA algorithm advances noticeably the performance and ability of the 2GRU× model. This optimization algorithm augments the 2GRU× model training phase and achieves better efficiency in the predicting CCRSFm. Additionally, the value of MBE shows that all models except the model 1 underestimated the corresponding measured values at the validation phase.

RMSE variations in the model 4 over the range of NHN used under the optimal hyper-parameter in the testing phase is displayed (Fig. 9). High NHN causes RMSE to grow as a result of overfitting, nevertheless, small NHN reduces network learning skill because of underfitting.

Performance comparison

In this modelling, to compare the skill and efficiency of models used in capturing the time series CCRSFm, a substantial factor called TLP (Total Learnable Parameters) is exploited, as suggested by Lin et al.18 (Table 4). The TLP is considered a crucial criterion for the discriminating forecasting performances and practical capacities of DL-based models. Moreover, it can also assess tendencies toward under-/over-fitting effects.

Based on Tables 4 and 5, though Model 1 has the extreme TLP value, Model 4 results in the best performance and surpasses other models by capturing the time series CCRSFm. The dominant reason for this is explainable by the high quantity of TLP in the model, 1 which led to an extremely unnecessary network capacity and accordingly, it prompts overfitting and hinders the optimization process. On the contrary, due to the lesser amount of TLP in model 2, it has a lesser network capacity, accordingly, leading to underfit. Generally, models 1 and 2 are not capable of monitoring and predicting time series CCRSFm in the study region due to poor performance. The model 4, thanks to the well-adjusted layer network structure and consequently TLP value, excelled over other models. It is owing to the well-proportioned TLP amount that it could hastily get the ideal weight sets − 1000 iterations in 33 s, while the model 1, for the uppermost TLP number, entails extra time to converge – 1000 iterations in 48 s.

Figure 10 matches pictographically the hydrograph plot for the measured and predicted temporal CCRSFm by model 4 under the ideal meta-parameters in the validation phase. Along with this figure, model 4 owing to its inventive advanced layer’s network structure can agreeably estimate the distribution of measured sequential CCRSFm and fit relatively the vacillations trend mostly in the peak and deepest values of CCRSFm that prove an acceptable unanimity.

In terms of distribution criteria, scatter diagrams for the measured and predicted time series CCRSFm by the models used during the validation stage are presented in Fig. 11A–D. By a visual judgment, it is noticeable that the predicted CCRSFm by the hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model is generally near to the exact line (i.e., 1:1) for abundant data points with minor scattering compared to the GRU model. It validates a high steadiness and best-performing approach with a satisfactory R2 of 0.79.

A violin plot is presented to concomitantly match the performance and skill of all models and single out the best model used in the validation phase (Fig. 12). By a visual evaluation, it can be concluded that the hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model relatively better fits the distribution of the observed temporal CCRSFm and could estimate to some extent exacter the peak and lowest values in comparison with the other models developed.

Summary and conclusion

In this study, different layer structures of GRU-based deep learning framework were developed to estimate the forecasting CCRSFm from Sep 1990 to Aug 2020 (360 months). In all models, to satisfy the long-period nonlinearity and non-stationary dilemmas, the seq2seq regression forecasting module is applied. The most worth mentioning outcomes of the modelling process are:

-

1.

The PCC and CAS data analysis methods approved that the Pm was the most influential predictor variable on CCRSFm to feed the models developed.

-

2.

The training-stage forms of all models were more precise than their validation counterparts.

-

3.

After several trials, the suggested hybrid 2GRU×–WOA model was accepted as the best-performing model by performance evaluation criteria to forecast CCRSFm. The optimal P-rate, NHN, and SAF tuned for this model were obtained to be 0.5, 70, and tanh-softsign, respectively. Integrating the 2GRU× model with WOA algorithm caused to increase in the value of R2 by 6.8% and reduced in the value of RMSE by 20.4%.

-

4.

By comparing the model structures developed and relevant TLP values, it can be concluded that inserting the Multiplication layer led to a more suitable layer network structure and well-adjusted TLP. So, for achieving effective DL-based models, an apt network structural, NHN, and well-balanced TLP value should be applied.

-

5.

In all models, growing P-rate value lessens convergence time. The model 1 for the high TLP quantity, necessitated more time to train – 1000 repetitions in 48 s.

The hybrid 2GRU×–WOA structure is a cutting-edge method as verified by its commendable accuracy and performance (verified statistically). It can therefore be employed as an intelligent smart model for monitoring and predicting time series river streamflow under different climatic conditions. This hybrid model is an easy-to-implement, cost-effective, dependable, and time-saving process. Its well-formed layer network structure prompted an apt response to TLP and engendered more precision than the standard GRU and Bi-GRU as the benchmark models in the same meta-parameters. Despite the advantages of a hybrid model, it has some constraints: it entails an extremely long period of detailed (i.e., regular measurements) precipitation data to predict CCRSFm in a study area, as the seq2seq regression module of forecasting was employed.

Even though this study evaluated the effects of different GRU-based model and WOA algorithm structures on forecasting CCRSFm, upcoming studies could examine other methods. For instance, modeling could integrate DNN models with the most up-to-date optimization algorithms, such as the Puma Optimizer (PO) and Mountain-Gazelle Optimizer (MGO). The results should be equated to the outcomes of the current study to obtain the most effective technique.

Data availability

Data used in this study are provided from the IMO (Iran Meteorological Organization) and will be available upon reasonable request.

Change history

16 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10510-3

Abbreviations

- MLMs:

-

Machine learning models

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- f:

-

Non-linear function

- LSTM:

-

Long short-term memory

- GRU:

-

Gated recurrent units

- Bi-GRU:

-

Bi-directional GRU

- WOA:

-

Whale optimization algorithm

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error (m3/s)

- STDV:

-

Standard deviation

- R2 :

-

Determination coefficient [-]

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variation

- NSE:

-

Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency [-]

- R:

-

Correlation coefficient [-]

- CCRSFm :

-

Mean monthly Chehel-Chai River’s streamflow (m3/s)

- Pm :

-

Mean monthly precipitation (mm)

- PCC:

-

Pearson’s correlation coefficient

- CAS:

-

Cosine amplitude sensitivity

- SAF:

-

State activation functions

- NHN:

-

Numbers of hidden neurons

- TLP:

-

Total learnable parameter

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error (m3/s)

- MBE:

-

Mean bias error (m3/s)

References

Papacharalampous, G., Koutsoyiannis, D. & Montanari, A. Advances in water resources quantification of predictive uncertainty in hydrological modelling by Harnessing the wisdom of the crowd: methodology development and investigation using toy models. Adv. Water Resour. 136, 103471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2019.103471 (2020).

Moges, E., Demissie, Y., Larsen, L. & Yassin, F. Review: sources of hydrological model uncertainties and advances in their analysis. Water 13, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13010028 (2021).

Horton, P., Schaefli, B. & Kauzlaric, M. Why do we have so many different hydrological models? A review based on the case of Switzerland. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. Water. 9, e1574. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1574 (2022).

Krysanova, V. et al. How the performance of hydrological models relates to credibility of projections under climate change. Hydrol. Sci. J. 63, 696–720. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2018.1446214 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Extreme atmospheric rivers in a warming climate. Nat. Commun. 14, 3219. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38980-x (2023).

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, 2(1), 2391 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896, 2391 pp.

Burgan, H. I., Vaheddoost, B. & Aksoy, H. Frequency analysis of monthly runoff in intermittent rivers. In World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2017 (pp. 327–334) (2017).

McDermott, T. K. J. Global exposure to flood risk and poverty. Nat. Commun. 13, 3529. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30725-6 (2022).

Khorrami, B., Pirasteh, S., Ali, S., Sahin, O. G. & Vaheddoost, B. Statistical downscaling of GRACE TWSA estimates to a 1-km Spatial resolution for a local-scale surveillance of flooding potential. J. Hydrol. 624, 129929 (2023).

Abbasi, M., Farokhnia, A., Bahreinimotlagh, M. & Roozbahani, R. A hybrid of random forest and deep Auto-Encoder with support vector regression methods for accuracy improvement and uncertainty reduction of long-term streamflow prediction. J. Hydrol. 597, 125717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125717 (2021).

Althoff, D., Rodrigues, L. N. & Bazame, C. H. Uncertainty quantification for hydrological models based on neural networks: the dropout ensemble. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 35, 1051–1067. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-021-01980-8 (2021).

Abbott, M. B., Bathurst, J. C., Cunge, J. A., O’connell, P. E. & Rasmussen, J. An introduction to the European hydrological System—Systeme hydrologique Europeen,SHE, 2: structure of a physically-based, distributed modelling system. J. Hydrol. 87 (1–2), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(86)90115-0 (1986).

Anandharuban, P., La Rocca, M. & Elango, L. A box-model approach for reservoir operation during extreme rainfall events: a case study. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 128, 229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-019-1258-7 (2019).

Silvestro, F., Ercolani, G., Gabellani, S., Giordano, P. & Falzacappa, M. Improving real-time operational streamflow simulations using discharge data to update state variables of a distributed hydrological model. Hydrol. Res. 52, 1239–1260. https://doi.org/10.2166/NH.2021.162 (2021).

Fathian, F., Mehdizadeh, S., Sales, A. K. & Safari, M. J. S. Hybrid models to improve the monthly river flow prediction: integrating artificial intelligence and non-linear time series models. J. Hydrol. 575, 1200–1213 (2019).

Vaheddoost, B., Safari, M. J. S. & Yilmaz, M. U. Rainfall-runoff simulation in ungauged tributary streams using drainage area ratio-based multivariate adaptive regression spline and random forest hybrid models. Pure Appl. Geophys. 180 (1), 365–382 (2023).

Rajib, A., Liu, Z., Merwade, V., Tavakoly, A. A. & Follum, M. L. Towards a large-scale locally relevant flood inundation modeling framework using SWAT and LISFLOODFP. J. Hydrol. 581, 124406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124406 (2020).

Lin, H. et al. Time series-based groundwater level forecasting using gated recurrent unit deep neural networks. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 16 (1), 1655–1672 (2022).

Ghasemlounia, R., Gharehbaghi, A., Ahmadi, F. & Albaji, M. Developing a novel hybrid model based on deep neural networks and discrete wavelet transform algorithm for prediction of daily air temperature. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 17, 2723–2737 (2024).

Ahmadi, F., Ghasemlounia, R. & Gharehbaghi, A. Machine learning approaches coupled with variational mode decomposition: a novel method for forecasting monthly reservoir inflows. Earth Sci. Inf. 17 (1), 745–760 (2024).

Gharehbaghi, A. & Ghasemlounia, R. Application of AI approaches to estimate discharge coefficient of novel kind of sharp-crested V-notch weirs. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 148 (3), 04022001 (2022).

Gharehbaghi, A. et al. A comparison of artificial intelligence approaches in predicting discharge coefficient of streamlined weirs. J. Hydroinform. 25 (4), 1513–1530 (2023).

Gharehbaghi, A., Ghasemlounia, R., Latif, S. D., Haghiabi, A. H. & Parsaie, A. Application of data-driven models to predict the dimensions of flow separation zone. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30 (24), 65572–65586 (2023).

Gharehbaghi, A., Ghasemlounia, R., Vaheddoost, B. & Ahmadi, F. Development of deep learning approaches for drought forecasting: a comparative study in a cold and semi-arid region. Earth Sci. Inf. 18 (1), 78 (2025).

Mehr, A. D., Kahya, E. & Yerdelen, C. Linear genetic programming application for successive-station monthly streamflow prediction. Comput. Geosci. 70, 63–72 (2014).

Anusree, K. & Varghese, K. O. Streamflow prediction of Karuvannur river basin using ANFIS, ANN and MNLR models. Proc. Technol. 24, 101–108 (2016).

Muhammad Adnan, R. et al. Application of soft computing models in streamflow forecasting. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Water Management, vol. 172 123–134 (Thomas Telford Ltd, 2019).

Amisigo, B. A., Van de Giesen, N., Rogers, C., Andah, W. E. I. & Friesen, J. Monthly streamflow prediction in the Volta basin of West Africa: A SISO NARMAX polynomial modelling. Phys. Chem. Earth (Pt AB C). 33 (1–2), 141–150 (2008).

Yurekli, K., Kurunc, A. & Ozturk, F. Application of linear stochastic models to monthly flow data of Kelkit stream. Ecol. Model. 183 (1), 67–75 (2005).

Chen, Y. H. & Chang, F. J. Evolutionary artificial neural networks for hydrological systems forecasting. J. Hydrol. 367 (1–2), 125–137 (2009).

Wu, C. L. & Chau, K. W. Data-driven models for monthly streamflow time series prediction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 23 (8), 1350–1367 (2010).

Rasouli, K., Hsieh, W. W. & Cannon, A. J. Daily streamflow forecasting by machine learning methods with weather and climate inputs. J. Hydrol. 414, 284–293 (2012).

Sun, A. Y., Wang, D. & Xu, X. Monthly streamflow forecasting using Gaussian process regression. J. Hydrol. 511, 72–81 (2014).

Masselot, P., Dabo-Niang, S., Chebana, F. & Ouarda, T. B. Streamflow forecasting using functional regression. J. Hydrol. 538, 754–766 (2016).

Erdal, H. I. & Karakurt, O. Advancing monthly streamflow prediction accuracy of CART models using ensemble learning paradigms. J. Hydrol. 477, 119–128 (2013).

Lima, A. R., Cannon, A. J. & Hsieh, W. W. Forecasting daily streamflow using online sequential extreme learning machines. J. Hydrol. 537, 431–443 (2016).

Atiquzzaman, M. & Kandasamy, J. Robustness of extreme learning machine in the prediction of hydrological flow series. Comput. Geosci. 120, 105–114 (2018).

Feng, Z. K. et al. Parallel Cooperation search algorithm and artificial intelligence method for streamflow time series forecasting. J. Hydrol. 606, 127434 (2022).

Hah, D., Quilty, J. M. & Sikorska-Senoner, A. E. Ensemble and stochastic conceptual data-driven approaches for improving streamflow simulations: exploring different hydrological and data-driven models and a diagnostic tool. Environ. Model. Softw. 157, 105474 (2022).

Sa’adi, Z. et al. Comparative assessment of empirical random forest family’s model in simulating future streamflow in different basin of Sarawak, Malaysia. J. Atmos. Sol -Terr Phys. 265, 106381 (2024).

Moknatian, M. & Mukundan, R. Uncertainty analysis of streamflow simulations using multiple objective functions and bayesian model averaging. J. Hydrol. 617, 128961 (2023).

Gizaw, M. S. & Gan, T. Y. Regional flood frequency analysis using support vector regression under historical and future climate. J. Hydrol. 538, 387–398 (2016).

Tongal, H. & Booij, M. J. Simulation and forecasting of streamflows using machine learning models coupled with base flow separation. J. Hydrol. 564, 266–282 (2018).

Achieng, K. O. Averaging multi-climate model prediction of streamflow in the machine learning paradigm. In Advances in Streamflow Forecasting 239–262 (Elsevier, 2021).

Soo, E. Z. X. et al. Streamflow simulation and forecasting using remote sensing and machine learning techniques. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15 (12), 103099 (2024).

Cho, K. et al. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. ArXiv 1406.1078 (2014). https://doi.org/10.48550/ArXiv.1406.1078

Karamvand, A., Hosseini, S. A. & Azizi, S. A. Enhancing streamflow simulations with gated recurrent units deep learning models in the flood prone region with low-convergence streamflow data. Phys. Chem. Earth (Pt AB C). 136, 103737 (2024).

Tao, L., Nan, Y., Cui, Z., Wang, L. & Yang, D. An explainable bayesian gated recurrent unit model for multi-step streamflow forecasting. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 57, 102141 (2025).

He, M. et al. Streamflow prediction in ungauged catchments through use of catchment classification and deep learning. J. Hydrol. 639, 131638 (2024).

Hou, S., Wei, J., Hou, M., Xu, J. & Han, L. A hydrological knowledge-informed LSTM model for monthly streamflow reconstruction using distributed data: application to typical rivers across the Tibetan plateau. J. Hydrol. 649, 132409 (2024).

Zhou, Y., Duan, Y., Yao, H., Li, X. & Li, S. Incorporating hydrological constraints with deep learning for streamflow prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 259, 125379 (2025).

Safari, M. J. S., Arashloo, S. R. & Mehr, A. D. Rainfall-runoff modeling through regression in the reproducing kernel hilbert space algorithm. J. Hydrol. 587, 125014 (2020).

Mehr, A. D. & Safari, M. J. S. Genetic programming for streamflow forecasting: a concise review of univariate models with a case study. In Advances in Streamflow Forecasting 193–214 (Elsevier, 2021).

Nazeri Tahroudi, M., Mirabbasi, R., Ramezani, Y. & Ahmadi, F. Probabilistic assessment of monthly river discharge using copula and OSVR approaches. Water Resour. Manag. 36 (6), 2027–2043 (2022).

Ahmadi, F., Tohidi, M. & Sadrianzade, M. Streamflow prediction using a hybrid methodology based on variational mode decomposition (VMD) and machine learning approaches. Appl. Water Sci. 13 (6), 135 (2023).

Eslamitabar, V., Ahmadi, F., Sharafati, A. & Rezaverdinejad, V. River flow simulation based on empirical mode function signals and random forest algorithm. Acta Geophys. 73, 1801–1817 (2025).

Eslamitabar, V., Ahmadi, F., Sharafati, A. & Rezaverdinejad, V. Bivariate simulation of river flow using hybrid intelligent models in sub-basins of lake urmia, Iran. Acta Geophys. 71, 873–892 (2023).

Floudas, C. A. & Gounaris, C. E. A review of recent advances in global optimization. J. Glob Optim. 45, 3–38 (2009).

Mirjalili, S. & Lewis, A. The Whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 95, 51–67 (2016).

Jia, F., Zhu, Z. & Dai, W. Short-term forecasting of streamflow by integrating machine learning methods combined with metaheuristic algorithms. Expert Syst. Appl. 245, 123076 (2024).

Nguyen, D. H., Le, X. H., Anh, D. T., Kim, S. H. & Bae, D. H. Hourly streamflow forecasting using a bayesian additive regression tree model hybridized with a genetic algorithm. J. Hydrol. 606, 127445 (2022).

Zhao, X. et al. Enhancing robustness of monthly streamflow forecasting model using gated recurrent unit based on improved grey Wolf optimizer. J. Hydrol. 601, 126607 (2021).

Adnan, R. M. et al. Improving streamflow prediction using a new hybrid ELM model combined with hybrid particle swarm optimization and grey Wolf optimization. Knowl. -Based Syst. 230, 107379 (2021).

Adnan, R. M. et al. Least square support vector machine and multivariate adaptive regression splines for streamflow prediction in mountainous basin using hydro-meteorological data as inputs. J. Hydrol. 586, 124371 (2020).

Luo, X. et al. J. A hybrid support vector regression framework for streamflow forecast. J. Hydrol. 568, 184–193 (2019).

He, Y., Yan, Y., Wang, X. & Wang, C. Uncertainty forecasting for streamflow based on support vector regression method with fuzzy information granulation. Energy Procedia. 158, 6189–6194 (2019).

Granata, F., Di Nunno, F. & Pham, Q. B. A novel additive regression model for streamflow forecasting in German rivers. Results Eng. 22, 102104 (2024).

Xu, L. et al. Investigating the potential of EMA-embedded feature selection method for ESVR and LSTM to enhance the robustness of monthly streamflow forecasting from local meteorological information. J. Hydrol. 636, 131230 (2024).

Heddam, S. et al. Hybrid river stage forecasting based on machine learning with empirical mode decomposition. Appl. Water Sci. 14 (3), 46 (2024).

Parsaie, A. et al. G. Novel hybrid intelligence predictive model based on successive variational mode decomposition algorithm for monthly runoff series. J. Hydrol. 634, 131041 (2024).

Ahmed, A. N., Van Lam, T., Hung, N. D., Van Thieu, N. & Kisi, O. El-Shafie, A. A comprehensive comparison of recent developed meta-heuristic algorithms for streamflow time series forecasting problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 105, 107282 (2021).

Shukla, R. et al. Modeling of stage-discharge using back propagation ANN-, ANFIS-, and WANN-based computing techniques. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 147, 867–889 (2022).

Cui, Z. et al. Real-time rainfall-runoff prediction using light gradient boosting machine coupled with singular spectrum analysis. J. Hydrol. 603, 127124 (2021).

Xie, T. et al. Hybrid forecasting model for non-stationary daily runoff series: a case study in the Han river basin, China. J. Hydrol. 577, 123915 (2019).

Yaseen, Z. M. et al. Novel approach for streamflow forecasting using a hybrid ANFIS-FFA model. J. Hydrol. 554, 263–276 (2017).

Sobhani, A., Asgari, H. R., Noura, N., Ownegh, M. & Sakieh, Y. Application of land-use management scenarios to mitigate desertification risk in Northern Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 76, 1–15 (2017).

Shakib, H. S. & Shojarastegari, H. Climate change impacts and water resources management: Chehel-Chai basin, Iran. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 15 (4), 741–754 (2017).

Momeni, E., Nazir, R., Armaghani, D. J. & Maizir, H. Prediction of pile bearing capacity using a hybrid genetic algorithm-based ANN. Meas 57, 122–131 (2014).

Lawrence, S., Back, A. D., Tsoi, A. C. & Giles, C. L. On the distribution of performance from multiple neural network trials. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 8 (6), 1507–1517 (1997).

Graves, A. & Schmidhuber, J. Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM and other neural network architectures. Neural Netw. 18 (5–6), 602–610 (2005).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. LSTM can solve hard long time lag problems. In Proceedings of 1996 Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 473–479). Denver, United States: MIT Press (1997).

Bengio, Y. Learning deep architectures for al. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2 (1), 1–127 (2007).

Danesh, M., Gharehbaghi, A., Mehdizadeh, S. & Danesh, A. A comparative assessment of machine learning and deep learning models for the daily river streamflow forecasting. Water Resour. Manag. 39, 1911–1930 (2025).

Gao, S. et al. Short-term runoff prediction with GRU and LSTM networks without requiring time step optimization during sample generation. J. Hydrol. 589, 125188 (2020).

Ghasemlounia, R., Gharehbaghi, A., Ahmadi, F. & Saadatnejadgharahassanlou, H. Developing a novel framework for forecasting groundwater level fluctuations using Bi-directional long Short-Term memory (BiLSTM) deep neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 191, 106568 (2021).

Shen, C. A transdisciplinary review of deep learning research and its relevance for water resources scientists. Water Resour. Res. 54 (11), 8558–8593 (2018).

Adnan, R. M. et al. Harnessing deep learning and snow cover data for enhanced runoff prediction in snow-Dominated watersheds. Atmos 15 (12), 1407 (2024).

Jamei, M. & Et Quantitative improvement of streamflow forecasting accuracy in the Atlantic zones of Canada based on hydro-meteorological signals: A multi-level advanced intelligent expert framework. Ecol. Inf. 80, 102455 (2024).

Watkins, W. A. & Schevill, W. E. Aerial observation of feeding behavior in four Baleen whales: Eubalaena glacialis, Balaenoptera borealis, Megaptera Novaeangliae, and Balaenoptera physalus. J. Mammal. 60 (1), 155–163 (1979).

Goldbogen, J. A., Friedlaender, A. S., Calambokidis, J., Mckenna, M. F. & Simon, M. Nowacek, D. P. Integrative approaches to the study of Baleen Whale diving behavior, feeding performance, and foraging ecology. BioScience 63 (2), 90–100 (2013).

Zhang, J., Zhu, Y., Zhang, X., Ye, M. & Yang, J. Developing a long Short-Term memory (LSTM) based model for predicting water table depth in agricultural areas. J. Hydrol. 561, 918–929 (2018).

Gharehbaghi, A., Ghasemlounia, R., Ahmadi, F. & Albaji, M. Groundwater level prediction with meteorologically sensitive gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural networks. J. Hydrol. 612, 128262 (2022).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Farshad Ahmadi: writing–review, investigation & editing. Redvan Ghasemlounia: Conceptualization, Methodology, writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing. Amin Gharehbaghi: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft preparation, Rasoul Mirabbassi: Supervision, Methodology, and Writing–review & editing. Ali Torabi Haghighi: Supervise, methodology, and writing–review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the name of the author Rasoul Mirabbasi, which was incorrectly given as Rasoul Mirabbassi. Additionally, Amin Gharehbaghi was incorrectly affiliated with ‘Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Istanbul Gedik University, Istanbul, 34876, Turkey.’ and Redvan Ghasemlounia was incorrectly affiliated with ‘Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Hasan Kalyoncu University, Şahinbey, Gaziantep, 27110, Turkey.’ Their correct affiliations are listed in the Correction Notice for this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gharehbaghi, A., Ghasemlounia, R., Ahmadi, F. et al. Developing a novel hybrid model based on GRU deep neural network and Whale optimization algorithm for precise forecasting of river’s streamflow. Sci Rep 15, 19436 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03185-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03185-3