Abstract

Active driving guidance functions are becoming increasingly prevalent in vehicles. In order to understand the demand characteristics, risk–benefit concerns and value judgments of different styles of drivers on active driving guidance, this paper focuses on the influence of driving style on the acceptance of active driving guidance. Based on the online questionnaire data, we use the extended model of technology acceptance and the concept of trust heuristic as the basic theory, divide the dimensions of driving styles, introduce the variables to measure acceptance, and construct a “driving style-active driving guidance acceptance” mental model by applying structural equation modeling (SEM).This model was constructed using SEM to clarify the association between different driving styles and the degree of acceptance of active driving guidance. The results showed that adventurous and angry drivers were significantly less receptive to active driving incentives; conservative drivers were significantly more receptive to active driving incentives; distracted drivers were more considerate of the conditions and popularity of active driving incentives; and anxious drivers were more sensitive to the perceived risk of active driving incentives and were less receptive to active driving incentives. The results of the study provide a basis for the development and promotion of new intelligent driving technologies such as active driving guidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Active driving guidance helps drivers to better adapt the driving environment by delivering real-time information to drivers, guiding driving directions, and reminding drivers of driving risks, including speed, path guidance, and reminders of road conditions ahead. For example, Baidu and Advanced map introduced the “traffic light countdown” function in 2022. Drivers’ evaluations of this feature are polarized, with some drivers believing that the feature can alleviate their anxiety during the redlight waiting period, prepare for starting and stopping in advance, and avoid signal blind spots, which is conducive to improving intersection safety. Other drivers think that there is a discrepancy between the countdown time and the actual traffic light time, and distracted attention to the navigation on the traffic light countdown increase the driving burden, the current application has not reached the expected results. Active driving guidance is a research hotspot in vehicle intelligence technology, which can provide personalized travel services for drivers and dynamically coordinate urban traffic supply and demand. To better promote active driving guidance, it is necessary to study the impact of the driver’s own differences on the acceptance.

Driving style refers to a driver’s habitual driving patterns, including driver’s attention, speed selection, following distance, and unconscious behavior1. Questionnaire survey is often used to assess the impact of large-scale driving style2,3,4, and measurement tools include the Driver Style Questionnaire (DSQ), the Multidimensional Driving Style Inventory (MDSI) etc. DSQ is mainly used in studies of driver selection, training and traffic safety education, but it is less adaptive to general scenarios and is infrequently used. MDSI defines the structure of driving style comprehensively for the first time and is widely used. However, due to extensive design items and complex analysis, it is seldom used in research. The subsequent revision of the Chinese version of the Multidimensional Driving Style Inventory (MDSI-C)5 has streamlined the classification of the original MDSI to better adapt the characteristics of Chinese drivers, but it focuses on non-adaptive driving styles such as adventurous and angry, and does not cover adaptive driving styles such as safety and caution.

Acceptance mainly refers to the degree of public understanding and trust of something, etc., and is usually investigated with the help of scales6. Only when drivers’ acceptance reaches a certain level will it be widely adopted and realize its potential benefits7. Individual driver differences have a significant impact on the acceptance of active driving guidance8,9. Scholars have investigated the impact of individual driver differences on driving guidance acceptance at the technical level. Li10 investigated the effects of drivers’ personal attributes on traffic guidance acceptance through a questionnaire survey and quantified their time tolerance, time saving, and detour distance boundaries. Chen et al.11 constructed a Logit model based on questionnaire data to analyze the influence of driver personality on the acceptance of guidance and proposed a vehicle parallel guidance strategy with actual passing time as the constraint.

In terms of acceptance models, Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is widely used to study users’ intentions and acceptance of emerging technologies, including mainstream theoretical models represented by the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the innovation diffusion theory (IDT), and the technology acceptance model (TAM) etc.12. The TPB theory considers social influence and the individual’s perceptual control, comprehensively explains the formation of behavioral intentions, but it focuses more on rational reasoning and neglects the influence of emotional factors on behavior, thus it has limited explanatory power for intention and behavior13. The IDT is suitable for studying the market diffusion and innovations dissemination, but the model is more complex and requires a large amount of data for analysis. The TAM model mainly focuses on perceived usefulness and ease of use, which is simple and easy to operationalize and understand. However, since it only considers two aspects of technology acceptance from a subjective point of view, it needs to be combined with new theories to improve the explanatory power when applied to different domains14.

When studying the relationship between different variables, previous studies often use correlation, regression model, structural model, etc. Correlation model is mainly used to measure the magnitude of correlation between two variables. Regression model reveals the effect of independent variables on Y and the degree of influence of the respective variables through modeling. The structural equation modeling (SEM) is a statistical analysis technique that includes factor and path analysis, which allows for the study of direct or indirect relationships between multiple variables while permitting hypothesis testing for complex theoretical models such as mediating and moderating effects. Since the dependent variable in this paper cannot be measured directly through data, we consider using SEM to establish the model relationships between variables.

To summarize, previous studies have provided mature experiences for the investigation of driving styles and technology acceptance, but there are fewer acceptance studies oriented to active driving guidance technology, especially the lack of technology promotion studies based on differentiated driving styles. Therefore, this study designs a survey scale to investigate the appropriate age group of drivers, obtains data on driving style and acceptance, establishes a structural model, and analyzes the influence and degree of trust and willingness to use active driving guidance by different driving styles. This will provide a basis for understanding the needs of drivers with different styles and improving the practicality of active driving inducement. The main contributions of the present study are as follows: (1) A multi-dimensional survey method combining subjective reports and objective data analysis was adopted to link driving style differences with the acceptance of active driving guidance technology for the first time, revealing the complex coupling relationship between driving style and the acceptance of active driving guidance technology. (2) Considering the influence of mediating effects, a structured model was developed to quantitatively assess the effectiveness of driving style on trust and willingness to use active driving guidance technology.

Methods

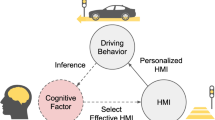

Theoretical models of driving style and active driving guidance acceptance

Considering the scale structure, scope of application, reliability and validity of the questionnaire, and characteristics of domestic drivers, the MDSI-C5 was developed based on the behavioral patterns and psychological traits of Chinese drivers, which can more accurately represent the domestic driving situation and is more targeted, but because it mainly considers non-adaptive driving styles and lacks the study of adaptive styles, which are crucial for understanding drivers’ overall driving behaviors and safety awareness. Therefore, this paper integrates the conservative driving style in the original MDSI based on the MDSI-C, and divides the driving style into five dimensions: anxiety, angry, distraction, adventurous, and conservatism.

TAM and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology(UTAUT) model are widely used to explain and predict technology acceptance15,16. Trust, behavioral attitudes, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and perceived risk were found to have a key impact on acceptance in the summary of research findings on acceptance of automated driving technologies by Jing P et al.17.

Perceived usefulness and ease of use are the main determinants of the TAM18,19, Perceived usefulness refers to the users’ perception of the usefulness of a product or technology for themselves, and perceived ease of use refers to the users’ perception of the convenience of the product or technology. Some scholars have used the model to study users’ willingness to use VR platforms, and concluded that both perceived usefulness and ease of use have an impact on acceptance20.

Since active driving guidance (traffic light countdown) has been implemented in some cities, when considering perceived ease of use, conditions such as the popularity of the technology and usage scenarios need to be further investigated. The UTAUT improves the model’s ability to interpret technology acceptance and use behavior by integrating various factors and taking use conditions as variables15. At the same time, some studies have shown that the use conditions have a significant impact on the acceptance of technology21,22.

In addition, in the decision-making process, people tend to choose a technology with higher benefits and lower risks. A number of studies have shown that perceived risk has a negative effect on technology acceptance23,24. Therefore, this paper further integrates the risk theory based on the consideration of perceived usefulness and use conditions.

In addition, trust also affects the public’s perception of the benefits and risks of new technologies and thus acceptance25,26. Some studies have shown that the level of public trust in technology is positively correlated with its acceptance27. On the results of studies on public trust in technology, trust heuristic models28,29 are often used to illustrate the relationship between trust and acceptance.

Behavioral intention is a key factor to understand the adoption process of a new technology, which involves users’ attitudes, willingness, and ultimately actual use behaviors toward the new technology. Numerous studies have been conducted to show that user behavioral intention has a significant positive effect on technology acceptance30,31,32.

In summary, we adds the perceived risk factor to the TAM and trust heuristic, and explores five variables: perceived usefulness, usage conditions, perceived risk, behavioral intention, and trust. In addition, since previous studies mainly explored the main effect of a factor on acceptance, and research on the mediating moderating effect between factors is very limited33,34,35, this paper considers the mediating moderating effect of latent variables to further explore the effect of different driving styles on acceptance.

Structural equation modeling

Because the data of driving style and acceptance cannot be measured directly, SEM has the ability to deal with both explicit and latent variables at the same time, and can quantify the multidimensional causal relationship between variables (e.g., direct and mediated effects) through path analysis, which is especially suitable for verifying the theoretical hypothesis of the chain of “Driving Style→Acceptance”. Compared with traditional methods such as logistic regression, SEM can effectively reveal the complex mechanisms of interaction between latent variables. At the level of method applicability, SEM shows two comparative advantages: first, compared with the “black box” characteristics of decision trees and other machine learning methods, SEM has a clear model interpretation, which is more suitable for the research goal of theoretical relationship verification; second, SEM is robust to small sample data, which can effectively solve the problem of sampling data volume limitations, avoiding the dependence on large data volume of machine learning methods. Therefore, this paper constructs a structural equation model of ‘driving style—active driving inducement acceptance’ to study the relationship between different driving styles and active driving inducement acceptance and the degree of correlation. The mathematical expression of SEM is explained by three equations:

(1) and (2) are measurement models, and (3) is the structural model. X and Y are the observed variables of exogenous and endogenous latent variables; \(\eta\) and \(\xi\) are exogenous and endogenous latent variables; ΛX and ΛY represent the factor loading matrices of X on ξ and Y on η; \(\varepsilon\) and \(\delta\) are the observation errors of X and Y, respectively; B and Γ are the coefficient matrices of the structural equation, where B represents the relationship between endogenous latent variables, and A represents the effect of exogenous latent variables on endogenous latent variables; ζ is the residual term of each variable in the structural equation.

Ethics statement

Participants in this study were voluntary and anonymous. Respondents were informed of the main purpose of the study and informed consent was given before starting the online questionnaire. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and the study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Changsha University of Science and Technology and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The questionnaire consists of 40 questions (Table 1). The first part covers personal information; the second part is a driving style survey containing five dimensions: distraction, anxiety, conservative, adventurous and angry; the third part is a survey on acceptance, covering five variables: perceived usefulness, perceived risk, trust, usage conditions, and behavioral intention. The items are measured using a Likert 5-point scale, where 1 indicates strongly “disagree or not applicable”, 2 indicates “disagree or not applicable”, 3 indicates “neutral”, 4 indicates “somewhat agree or applicable”, and 5 indicates “strongly agree or applicable”. A total of 351 online questionnaires were distributed in the study, and 37 invalid questionnaires were excluded, resulting in the final collection of 314 valid questionnaires (Table 2). The effective response rate was 89.5%. Table 3 lists the average scores and standard deviations of the samples across various items.

Significance test

Based on the survey data, we employed the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) method to examine the differences in driving styles and acceptance of active driving guidance among various categories of survey respondents When significant differences are observed, further analysis is conducted. The results of the significance test are shown in Table 4.

Given that large samples (N = 314) may amplify statistical significance, the present study used a dual-threshold judgment criterion: results that satisfy both p < 0.05 and a bias of η2 ≥ 0.06 (moderate effect) are considered to be both theoretically and practically significant. As shown in Table 4, although the effects of gender on Anxious (η2 = 0.015), Conservative (η2 = 0.014), and Behavioral intention (η2 = 0.017) reached statistical significance, the effect sizes were all in the small effect range (η2 < 0.06). Similarly, the effects of education on Distracted (η2 = 0.048), Perceived usefulness (η2 = 0.017), Perceived risk (η2 = 0.04), and Behavioral intention (η2 = 0.038), of driving age on Perceived risk (η2 = 0.048), as well as of average weekly driving time on Trust (η2 = 0.05), Usage conditions (η2 = 0.049), and Behavioral intention (η2 = 0.036) were also characterized by small effects. Therefore, the actual strength of the effects of these variables may be limited, and their significance is more likely to reflect sample size effects than substantive associations. Further analysis was conducted on the relationships of variables that were statistically significant and had medium effects and above.

Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 illustrate the significant differences in driving style and acceptance scores between different drivers. In terms of gender, male drivers scored significantly higher than female drivers on the distracted, adventurous, and angry dimensions, and their behavioral intention to perceive and use usefulness and risk on the acceptance dimension were higher too, while female drivers scored higher on the anxious dimension. In terms of age, drivers aged 18–23 years old scored higher than drivers of other ages in all driving style dimensions, probably because this group has less driving experience, greater emotional fluctuations when driving, and psychological quality is poorer. except for the anxiety dimension, drivers aged 35–45 years old scored lower than other age groups in all driving style dimensions, probably because with increasing age and driving experience, they are more skillful in driving vehicles and have less emotional fluctuations. In terms of acceptability, younger drivers were more concerned with perceived risk, while older drivers tend to focus more on perceived usefulness. Regarding driving experience, as driving experience increases, drivers become more capable of coping with various traffic situations and emergencies, and therefore feel less anxiety when facing complex traffic environments and possess more accurate judgments about potential risk. In terms of average driving time, drivers who drive an average of 20–40 hours per week have the lowest scores for anxious, trust, usage conditions, and behavioral intention, possibly due to the fact that appropriate driving time allows this segment to maintain proficient driving skills but not fatigue due to overdriving. Furthermore, these drivers may be neither as curious and receptive to new technology as novice drivers nor as experienced drivers who have an extremely high sense of control and confidence in the driving environment. In terms of education, the higher the level of education, the generally higher scores on the dimensions of driving style and acceptance, which may be the result of this segment of drivers being more attentive to a variety of potential situations behind the wheel.

Reliability and validity tests of variables

Firstly, based on the KMO and Bartlett tests, the KMO value is 0.870 (>0.8), and the significance P value is 0.001, indicating a strong correlation between the questionnaire variables, which is suitable for factor analysis. Then principal component analysis was conducted on the driving style and acceptance data, and the cumulative variance contribution rates of the four extracted principal components were 78.941% and 69.3%, respectively, which means that adventurous and angry in driving style, and trust and behavioral intention in acceptance were merged into one category, which can better explain the original data. Afterwards, a reliability and validity test was conducted on the valid sample data (Table 5), indicating that the Cronbach’s α of each variable is greater than 0.7, indicating good reliability of the questionnaire data. AVE greater than 0.5 or CR greater than 0.7 indicates that the questionnaire has good internal consistency and convergent validity. Subsequent analysis of discriminant validity (Table 6) showed that the AVE root sign values for each latent variable factor were greater than the Pearson correlation coefficient values for the other factors, and that the discriminant validity of the scale data was good for all of them, and there was a certain degree of correlation between the factors.

Driving style-acceptance modeling

Structural equation modeling verifies the relationship by calculating standardized path coefficients between latent variables and their significance. A positive coefficient indicates a positive correlation and a negative one a negative correlation. Significance can be judged by the critical ratio (C.R.) and P-value: C.R. is the ratio of the path coefficient (Estimate) to the standard error (S.E.), whose absolute value is greater than 1.96 indicates significance; a P-value of less than 0.05 indicates that the hypothesis is valid. The path coefficients are shown in Table 7.

Figure 6 shows the final model diagram. After combining mediation effect tests, making path restrictions and model expansion modifications, namely deleting paths with too small factor loadings and path coefficients that do not meet the conditions, and adding new paths based on the AMOS Modification Index (MI), the model fit was tested. The results are shown in Table 8.

Model estimation results

-

1.

The coefficient value of FN3 and MX3 in the dimension of adventurous and angry is 0.74 and 0.61, indicating that these behaviors are often found in drivers with more risky and angry driving styles. These drivers tend to pursue excitement and reckless behavior, are easily influenced by the surrounding driving environment and other road users, and have a weak perception of risk. Also, according to the result analysis, these drivers are insensitive to the conditions and trust of using the active driver guidance function, and their willingness to use the function is low. This low acceptance may stem from a high level of confidence in their own driving ability, which in turn leads to a lack of trust and perceived usefulness of the technology.

-

2.

Distracted style drivers are more trusting of active driving guidance and pay more attention to the conditions of using this function, but because this group of drivers is not concentrating on their own driving, so their perception of the usefulness of active driving guidance is weaker, and there is no significant relationship between this group of drivers’ driving styles and their acceptance of active driving guidance.

-

3.

The coefficient value of BS2 is the largest in the conservative dimension, which indicates that the more conservative drivers are more cautious, and they are able to understand the driving behaviors of other drivers and are always ready to react to the unexpected actions of other drivers. The analysis of the related path coefficients shows that the conservative style drivers are the most sensitive to the usefulness of the guidance and focusing more on the safety and usefulness of this feature, and they have higher requirements for the conditions of use and trust, and decide whether to use the technology or not through the influence of perceived usefulness.

-

4.

Among the anxiety dimension, JL2 corresponds to the largest coefficient value, indicating that drivers with high scores on the anxiety dimension are more likely to feel nervous while driving. Positive significance is extremely strong in its path to perceived risk, indicating that anxious style drivers worry more about the risk induced by active driving and do not perceive its usefulness significantly.

-

5.

Among the usage conditions and trust dimensions, the coefficient value corresponding to SYTJ3 is the largest, indicating that the public’s trust level for active driving guidance is largely affected by the popularity of the active driving guidance function, and that in real driving scenarios, the road conditions are complicated, and there are signal blind zones in the countdown that are difficult to access, and it is difficult to anticipate in many cases, and so on.

-

6.

The coefficient value of GZFXX3 is the largest in perceived risk, which indicates that the public is more worried than the other observational variables that the additional countdown information added by the active driving guidance will increase the driver’s task load and distract attention when driving, and will not bring additional safety protection.

-

7.

Among the variables of perceived usefulness, GZYYX2 has the largest coefficient value, which indicates that the public is more inclined to believe that the active driving guidance can give the countdown information of traffic lights in time, which is convenient for adjusting the driving behavior in time, compared with other variables.

-

8.

Among the variables of behavioral intention, XWYX2 has the largest coefficient value, which indicates that the surveyed drivers are more concerned about the impact of this function on the society than their own acceptance of the active driving guidance.

Discussion and conclusions

According to the analysis of questionnaire data, factors such as driver’s gender, age, education level, driving experience, and average driving time all have a certain influence on driving style and active driving guidance. Based on the subsequent SEM analysis results, it can be concluded that driving style significantly affects the acceptance of active driving guidance.

In the driving style survey, male drivers scored higher than female drivers in all other dimensions except the conservative dimension, suggesting that gender characteristics can influence drivers’ decision-making styles, which are reflected in their daily driving behaviors. This is consistent with previous research findings36. Furthermore, in previous studies examining gender differences in technology acceptance, it has been generally observed that men have a higher acceptance of autonomous vehicles than women37,38. Men tend to perceive potential risks less sensitively33,39and have a more optimistic expectation of new technologies34, which aligns with the results of this study, where male drivers exhibit a greater perception of the usefulness and danger of new technologies than female drivers. However, since the current research is only based on national-level data40, future studies could consider exploring gender differences in active driving acceptance based on different countries and regions. Younger drivers, who are not fully mature psychologically and physiologically, experience greater emotional fluctuations when facing driving stress and complex traffic situations, with significantly higher anxiety scores compared to other age groups. At the same time, this group is more optimistic about new technologies and more sensitive to potential risk, with a stronger perception of usefulness and risk41. As driving experience and time increase, drivers gradually become more experienced, becoming more familiar and comfortable with vehicle control and handling diverse driving environments. We find that although anxiety decreases with an increase in average driving time, it increases after exceeding a certain threshold, possibly because excessive driving can lead to physical and mental fatigue, excessive psychological pressure, and a significant increase in anxiety. This is consistent with previous research findings42,43, and future research could further explore the relationship between driving time and anxiety, to comprehensively understand the impact of driving time on drivers’ psychological states, providing a basis for scientifically specifying driving rest systems and hourly limits.

In addition, in the survey of drivers’ preferred guidance methods, more than 75% of drivers preferred auditory forms such as voice announcements, and the least number of drivers chose visual forms such as text reminders, probably because drivers have limited attention span while driving, and compared with visual information processing, guidance methods such as voice announcements can provide a large amount of information in a short period of time, and reduce the driver’s visual load, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies44.The survey on drivers’ preferred guidance content shows that drivers are concerned about the red light countdown seconds reminder, status reminder, and recommended speed reminder. We can subsequently study the driving behavior of drivers with different guidance technology reminder methods and contents to obtain a more appropriate and safe form of guidance, including tactile, auditory, visual, etc., and the contents include speed induction, path induction, and countdown induction, etc.

According to the study on the influence of specific driving styles on different acceptance variables, drivers with adventurous and angry styles are less psychologically stable and more aggressive when driving. They have weaker lateral control of the vehicle, and often exhibit behaviors such as rapid acceleration, rapid deceleration, and frequent lane changes, and are more concerned about their own driving experience, with higher frequencies of violations, errors, and misoperations45. They have a weaker trust and usefulness of active driving guidance. and thus they are less receptive to active driving guidance. The acceptance of active driving guidance by distracted style drivers is affected by the conditions of use and trust, and drivers with higher scores pay more attention to the accuracy and popularity of active driving guidance, so subsequent consideration can be given to optimizing the technical algorithms and researching how to effectively interface the active driving inducement system with the city’s signal light system to achieve data sharing and real-time traffic control. On the other hand, drivers with conservative style pay more attention to the usefulness, usage conditions and trust of active driving guidance, and tend to realize more stable driving through guidance, so they have higher acceptance of active driving guidance. Anxious style drivers are less receptive to active driving guidance because this group is more sensitive to perceived risk during driving and will be more cautious in accepting a new technology.

In the mediation effect test, it was further discovered that distraction can influence perceived usefulness and behavioral intention by affecting usage conditions, trust, and perceived risk, while conservative can influence behavioral intention by affecting perceived usefulness, usage conditions, and trust. Previous studies have shown that perceived usefulness can indirectly exert a significant positive effect on the willingness to continue use through satisfaction, consumer satisfaction directly has a significant positive impact on the willingness to continue use46. This finding is similar to what we discovered in this study that by influencing variables such as perceived usefulness and trust, it can indirectly affect behavioral intention. Further exploration of other mediating or moderating variables can be conducted in the future.

In order to further capture the deeper motivation of driver behavior and understand the reasons for the low acceptance of active driving guidance, we conducted a return interview with this group of drivers: three core questions were set to ask: "In which scenarios would you actively turn off the traffic light countdown function? Why?", “Under what circumstances do you think this feature may increase the risk of driving?”, “How would you like to improve the prompting or interaction logic of this feature?” and summarized that the majority of the drivers are not aware of this feature. Through summarizing, we found that most of the drivers refused the feature because they had experienced system errors in the past driving process, which led to their own misjudgment, and their own habit of relying on their experience for a long time, which made them slow in adapting to the new technology. At the same time, a small number of drivers mentioned that they did not choose to use the technology due to the economic cost, the waste of cell phone traffic for a long period of time, or that the induction technology was a threat to their driving autonomy. Follow-up studies consider further consideration to examine the internal factors of low driver acceptance to provide more scientific recommendations for technology development.

In the mediation effect test, it was further discovered that distraction can influence perceived usefulness and behavioral intention by affecting usage conditions, trust, and perceived risk, while conservative can influence behavioral intention Previous studies have shown that perceived usefulness can indirectly exert a significant positive effect on the willingness to use the Internet. Previous studies have shown that perceived usefulness can indirectly exert a significant positive effect on the willingness to continue use through satisfaction, consumer satisfaction directly has a significant positive impact on the willingness to continue use. impact on the willingness to continue use. This finding is similar to what we discovered in this study that by influencing variables such as perceived usefulness and trust, it can indirectly affect behavioral intention. Further exploration of other mediating or moderating variables can be conducted in the future.

In terms of application, traffic management authorities can design safety education content for different driving style groups and differentiate publicity and training. For example, they can emphasize the risk-avoidance ability of the active driving guidance function for adventurous and angry drivers. Automakers can also develop intelligent systems that recognize driving styles based on the characteristics of drivers with different driving styles, while optimizing human-computer interaction interfaces and enhancing technological trust through transparent functional logic (e.g., visual risk prediction).

However, in the experiment we noticed some errors in drivers’ self-perception localization, which may have an impact on the classification results of driving styles. In order to further improve the accuracy of the study, the next study should combine the real-vehicle experimental method and utilize both subjective report data and objective driving data to classify the driving styles more accurately. In addition, since this study mainly investigates Chinese drivers and involves a limited variety of driving styles, more refined subtypes (e.g., calm, competitive, aggressive), etc., will be included in the future to further deepen its research on driving behavior. Considering that the current sample is skewed towards younger age groups, future research considers covering the entire age group based on the age composition of drivers in each country and verifying the impact of cultural factors through cross-national cooperation, focusing on examining moderating variables such as the degree of standardization of road infrastructure and differences in Telematics policies, to construct a framework for assessing cross-national technology acceptance. Meanwhile, given that drivers differ significantly in terms of personality, experience, and skill level, future research should explore the personalized preferences of drivers with different driving styles for the method and content of active guidance information release. To this end, the driver’s behavioral characteristics, psychological state, and driving environment can be considered comprehensively in the future, with a view to designing an intelligent driver assistance system that better meets the driver’s needs, thereby improving driving safety and comfort. On this basis, further research can also be conducted on how to improve driver behavior and promote road traffic safety through personalized guidance information.

Data availability

Raw data can be obtained from the corresponding author by reasonable request.

References

Li, X. Y. & Liu, S. W. Overview of driving style research. Auto Time 15, 189–190. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-9668.2020.15.086 (2020).

Mohammadnazar, A., Arvin, R. & Khattak, A. J. Classifying travelers’ driving style using basic safety messages generated by connected vehicles: Application of unsupervised machine learning. Transport. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 122, 102917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2020.102917 (2021).

Zang, Y. et al. How drivers perform under different scenarios: Ability-related driving style extraction for large-scale dataset. Accid. Anal. Prev. 196, 107445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2023.107445 (2024).

Chen, Y., Wang, K. & Lu, J. J. Feature selection for driving style and skill clustering using naturalistic driving data and driving behavior questionnaire. Accid. Anal. Prev. 185, 107022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2023.107022 (2023).

Sun, L. The Revision of Multidimensional Driving Style Inventory and the Association with Drivers’ Emotion Styles (Liaoning Normal University, 2014). https://doi.org/10.7666/d.Y2613421.

Tang, L., Qing, S., Xu, Z. & Zhou, H. Research review on public acceptance of autonomous driving. J. Traffic Transport. Eng. 20(02), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.19818/j.cnki.1671-1637.2020.02.011 (2020).

Post, J. M. M., Berfu Ünal, A., Veldstra, J. L., De Waard, D. & Steg, L. Acceptability of connected automated vehicles: Attributes, perceived behavioural control, and perceived adoption norm. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 102, 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2024.03.012 (2024).

Ahlstrom, C. & Kircher, K. Changes in glance behaviour when using a visual eco-driving system—A field study. Appl. Ergon. 58, 414–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2016.08.001 (2017).

Tu, R., Xue, S., Jiang, S. Y. & Chen, Q. Z. Drivers’ acceptance of eco-driving guidance assistance system based on technology acceptance model. J. Tongji Univ. 52(04), 592–603. https://doi.org/10.11908/j.issn.0253-374x.23404 (2024).

Li, L. H. & Cao, G. B. Traffic guidance route choice model based on the aspiration of driver. Highway 61(02), 137–141 (2016).

Chen, Z. Y., Han, Y. L., Chen, X. F., Yang, J. S. & Wang, R. C. Urban traffic parallel induction strategy based on driver acceptance. World Transport Convent. Wuhan https://doi.org/10.26914/c.cnkihy.2022.019813 (2022).

Yang, S. J., Chen, Y. Q., Wu, Y. P. & Hu, A. X. Study on the public acceptance of self-driving buses. J. Transport. Eng. 22(05), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.13986/j.cnki.jote.2022.05.006 (2022).

Zhu, J. X. Review on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Bull. Sport Sci. Technol. 28(04), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.19379/j.cnki.issn.1005-0256.2020.04.072 (2020).

Chen, X. Q. & Li, R. J. Analysis of mobile banking adoption study based on the use of TAM model—An example of international journals from 2015 to 2020. Adv. Soc. Sci. 009(9), 1483–1495 (2020).

Williams, M. D., Rana, N. P. & Dwivedi, Y. K. The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A literature review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 28(3), 443–488. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-09-2014-0088 (2015).

Smyth, J., Chen, H., Donzella, V. & Woodman, R. Public acceptance of driver state monitoring for automated vehicles: Applying the UTAUT framework. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 83, 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2021.10.003 (2021).

Jing, P. et al. Research of acceptance of autonomous vehicles technology based on mapping knowledge domain. J. Jiangsu Univ. 44(01), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-7775.2023.01.003 (2023).

Wang, S., Li, Z., Wang, Y., Zhao, W. & Liu, T. Evidence of automated vehicle safety’s influence on people’s acceptance of the automated driving technology. Accid. Anal. Prev. 195, 107381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2023.107381 (2024).

Sahebi, S., Heshami, S., Khojastehpour, M., Rahimi, A. & Mollajani, M. Assessing public perception of car automation in Iran: Acceptance and willingness to pay for adaptive cruise control. IATSS Res. 48(2), 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iatssr.2024.04.002 (2024).

Feng, Z. Z. & Zhou, W. L. Research on the influencing factors of tourists VR tourism willingness based on TAM model. China J. Commerce. 33(20), 86–90. https://doi.org/10.19699/j.cnki.issn2096-0298.2024.20.086 (2024).

Zhang, J. X., Zhang, H., Zhu, Y., Chen, X. & Xu, Q. Research on the factors influencing college students’online learning behavior based on UTAUT model. J. Hubei Norm. Univ. 42(02), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2096-3149.2022.02.008 (2022).

Li, W. L. Research on Influencing Factors of Tourists’ Willingness to Use Shared Cars Based on Modified UTAUTModel (Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, 2023). https://doi.org/10.27175/d.cnki.gjxcu.2023.001040.

Chen, Z. et al. Charging or Swapping? A study on the private Consumers’ acceptance of the electricity replenishment mode of new energy vehicles. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 107, 903–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2024.10.015 (2024).

Jiang, S. Y. & Guo, H. Y. Research on the willingness to use autonomous vehicles from the perspective of users. China Transport. Rev. https://doi.org/10.20164/j.cnki.cn11-1197/u.20241107.001 (2024).

Zhang, T. et al. The roles of initial trust and perceived risk in public’s acceptance of automated vehicles. Transport. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 98, 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2018.11.018 (2019).

Buckley, L., Kaye, S.-A. & Pradhan, A. K. Psychosocial factors associated with intended use of automated vehicles: A simulated driving study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 115, 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2018.03.021 (2018).

Palomo-Vélez, G., Contzen, N., Perlaviciute, G. & Steg, L. Trust in institutions and public acceptability of risky energy production: Testing the causal relationships in the context of Groningen earthquakes. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 96, 102927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102927 (2023).

Eiser, J. R., Miles, S. & Frewer, L. J. Trust, perceived risk, and attitudes toward food technologies. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32(11), 2423–2433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb01871.x (2002).

Wang, F. Research on the effects of trust in government on public acceptance of nuclear energy [Doctor]. University of Science and Technology of China. https://doi.org/10.27517/d.cnki.gzkju.2021.002336 (2021).

Tu, X. Understanding the lntention to adopt university library WeChat public platform. J. Inf. Resour. 6(01), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.13365/j.jirm.2016.01.064 (2016).

Koppel, S. et al. Factors influencing behavioral intentions to use conditionally automated vehicles. J. Saf. Res. 91, 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2024.10.006 (2024).

Zhao, C. L., Jin, S. Y., Wu, H. J. & Ding, L. Influence factors of automated valet parking acceptance and parking choice behavior. Sci. Techonol. Eng. 23(35), 15259–15268. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2023.35.042 (2023).

Kapser, S., Abdelrahman, M. & Bernecker, T. Autonomous delivery vehicles to fight the spread of Covid-19—How do men and women differ in their acceptance?. Transport. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 148, 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2021.02.020 (2021).

Hohenberger, C., Spörrle, M. & Welpe, I. M. How and why do men and women differ in their willingness to use automated cars? The influence of emotions across different age groups. Transport. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 94, 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2016.09.022 (2016).

Madigan, R., Louw, T., Wilbrink, M., Schieben, A. & Merat, N. What influences the decision to use automated public transport? Using UTAUT to understand public acceptance of automated road transport systems. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 50, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2017.07.007 (2017).

Shamoa-Nir, L. Road rage and aggressive driving behaviors: The role of state-trait anxiety and coping strategies. Transport. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 18, 100780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2023.100780 (2023).

Liljamo, T., Liimatainen, H. & Pöllänen, M. Attitudes and concerns on automated vehicles. Transport. Res. F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 59, 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.08.010 (2018).

Nielsen, T. A. S. & Haustein, S. On sceptics and enthusiasts: What are the expectations towards self-driving cars?. Transp. Policy 66, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.03.004 (2018).

Hulse, L. M., Xie, H. & Galea, E. R. Perceptions of autonomous vehicles: Relationships with road users, risk, gender and age. Saf. Sci. 102, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.10.001 (2018).

Torrao, G., Lehtonen, E. & Innamaa, S. The gender gap in the acceptance of automated vehicles in Europe. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 101, 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2023.11.002 (2024).

Günthner, T. & Proff, H. On the way to autonomous driving: How age influences the acceptance of driver assistance systems. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 81, 586–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2021.07.006 (2021).

Yang, L., Yang, Y., Song, Y. Z. & Zhang, Y. A review of influencing factors and ldentification methods of driver stress. J. Transport. Syst. Eng. Inf. Technol. 22(06), 40–67. https://doi.org/10.16097/j.cnki.1009-6744.2022.06.004 (2022).

Song, G. P. & Zhang, K. Effects of driving fatigue on moods. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-3611.2006.03.010 (2006).

Bilius, L.-B. & Vatavu, R.-D. A multistudy investigation of drivers and passengers’ gesture and voice input preferences for in-vehicle interactions. J. Intell. Transport. Syst. 25(2), 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/15472450.2020.1846127 (2021).

Hou, H. J., Jin, L. S., Guan, Z. W., Du, H. X. & Li, J. J. Effects of driving style on driver behavior. China J. Highway Transport 31(04), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.19721/j.cnki.1001-7372.2018.04.003 (2018).

Wu, B. & Liu, X. Y. A meta-analysis of continuance intention to use MOOCs. Adv. Soc. Sci. 12, 5962–5969. https://doi.org/10.12677/ASS.2023.1210818 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Nos. 2023JJ30055, 2021JJ40577), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52302385, 52102405), the Scientific Research Program of the Education Department of Hunan Province (Nos. 21B0335, 20B009), the Key Project of Hunan Provincial Department of Education (No. 19A010), and the Changsha Natural Science Foundation (No. KQ2202212) in the form of grants to WX.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.X. reviewed and revised the article and provided funding support. Y.Q. designed the research methodology, wrote initial drafts of the content of each section and collected the references. L.X. conceived the idea, determined the theme of the article, supervised the process. Y.H. supervised the process of revising manuscripts and other materials. All authors participated in the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang, W., Qiu, Y., Xing, L. et al. A questionnaire-based study of the effect of driving style on the acceptance of active driving guidance. Sci Rep 15, 19687 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03352-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03352-6