Abstract

This study systematically evaluated the efficiency of rose bengal and methylene blue as photosensitizers against the immature aquatic stages of Anopheles pharoensis. Genetic identification using the COI partial sequence confirmed the species, and the obtained sequence was submitted to GenBank (Accession No. PQ346929). Both photosensitizers exhibited 100% mortality in larvae I within 24 h at their highest concentrations, demonstrating strong biocidal activity. LC50 values for rose bengal increased from 1.50 ppm (24 h) and 1.34 ppm (48 h) in larvae I to 3.83 ppm (24 h) and 3.12 ppm (48 h) in pupae. Similarly, methylene blue showed LC50 values rising from 1.14 ppm (24 h) and 0.90 ppm (48 h) in larvae I to 2.91 ppm (24 h) and 2.51 ppm (48 h) in pupae, indicating stage-dependent susceptibility. Enzymatic responses revealed a progressive increase in acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity in the developmental stage, suggesting a physiological adaptation to the photosensitizers. Molecular docking against the AChE protein (PDB ID: 6xyu) confirmed insecticidal bioactivity, with methylene blue exhibiting superior binding affinity, aligning with the in-vitro larvicidal results. Furthermore, a Complex GAPI assessment confirmed the environmental sustainability of both photosensitizers, supporting their potential as eco-friendly alternatives for mosquito control. The use of Complex GAPI in assessing the environmental sustainability of photosensitizers in mosquito control represents a novel approach in the field of integrated pest management. This advancement not only aligns with the principles of green chemistry but also addresses the growing need for sustainable alternatives to traditional chemical insecticides. These findings highlight the feasibility of utilizing light-activated photosensitizers for sustainable vector management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mosquito-borne diseases are the most relevant arthropods in public health, especially Anopheles genera because of their responsibility in transmitting different human and animal diseases as malaria1. Malaria is a parasitic disease caused by Plasmodium protozoa and infects more than 240 million people worldwide causing more than 625 thousand deaths in 20212. To eliminate the spread of malaria, several strategies have been applied to control the prevalence of different Anopheles Sp.3. Different immature aquatic stages of Anopheles Sp. were usually targeted by synthetic chemical insecticides, but developing new control alternatives, which are more efficient, safe, and eco-friendly considered acceptable proper and urgent replacements to avoid the hazards of synthetic chemical insecticides4,5.

Photosensitizing agents, which are activated by sunlight, attracted more attention as a new generation of insecticide that is highly efficient and environmentally safe due to its rapid photodegradation in the visible light6. Photo-insecticides have been used in agriculture against crop pests7. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is used clinically to treat a wide range of medical conditions, including psoriasis, and atherosclerosis and has shown some efficacy in anti-viral treatments, including herpes. It also treats malignant cancers including head and neck, lung, bladder, and particular skin8. Also, this technology has been tested for the treatment of prostate cancer in a dog model and human prostate cancer patients9,10. In addition, PDT is recognized as a treatment strategy that is both minimally invasive and minimally toxic.

Evaluating the greenness of the method is essential for advancing environmental sustainability. This assessment encompasses a rigorous examination of several critical parameters, including solvent consumption, waste production, energy requirements, and process efficiency11. By applying green chemistry principles, this evaluation provides a quantitative measure of a method’s ecological impact, thereby facilitating the development of more sustainable practices and promoting adherence to environmental standards. The complex GAPI tool represents a significant advancement in the assessment of method greenness, providing a comprehensive and systematic approach for evaluation12.

The current study aimed at evaluating the impact of two major photosensitizers, rose bengal and methylene blue against different aquatic immature stages of the malarial vector, Anopheles pharoensis.

Materials and methods

Anopheles pharoensis colony

Larvae of Anopheles pharoensis were obtained from Medical Entomology institution, Dokki, Giza, Egypt and reared for several generations under controlled conditions of temperature (25 ± 2 °C), relative humidity (70 ± 10%) and photoperiod (12 L:12D) following a standard rearing procedure described by Hassanain et al.13 to provide immature stages needed for the bioassay.

Genetic identification of Aedes aegypti larvae

Extraction of DNA from mosquito larvae

Small pieces of the A. pharoensis specimens were inserted in 1.5 µL Eppendorf tubes for study. The PureLink® Genomic DNA Kits were used for DNA extraction (Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). In summary, 180–250 µL of tissue lysis buffer was added to each sample, and 10 µL of proteinase K was added to each 180 µL of tissue lysis solution. Then, for 4 h, the combination was kept at 56 degrees Celsius. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube as directed by the manufacturer (Invitrogen; Waltham, Massachusetts; USA). Following the addition of 200 µL of ethanol and 200 µL of Lysis/Binding Buffer, the lysate was vertexin. The solution was then placed in a spin column and centrifuged at 10,000 xg for one minute. DNA was eluted in 50 µL of elution solution after two washes with wash buffers and then kept at -20 °C.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

LCO1490 (5’-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3’) and LCO1490-R (5’-TAA ACT TCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT CA-3’) were used as the forward and reverse primers, respectively. A total of 50 µl was used for the PCR amplification process, with 25 µl used for the 2X master mix solution (i-Taq, iNtRON, Seongnam, Korea), 2 µl each of the 0.2 M primers, 4 µl of template DNA, 2 µl of BSA at 0.2 mg/mL, and 14.5 µl of nuclease-free water. First, tick DNA was denatured at 95 degrees Celsius for 10 min, then it was subjected to 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 degrees Celsius for 1 min, annealing at 46 degrees Celsius for 1 min, and extension at 72 degrees Celsius for 1 min. The last 10-minute extension was carried out at 72 degrees. The amplified DNA was seen on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and examined under a transilluminator to determine the PCR product’s quality and quantity (U.V. transilluminator, Spectroline, Westbury, USA).

Sequence analysis

Using a Macrogen reagent, the PCR products were isolated and purified (Seoul, Korea). Nucleotide sequences of A. pharoensis COI were aligned following single-strand DNA sequencing.

Assessment of photosensitizer activity

Rose bengal and Methylene blue (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company, Egypt) with molecular weights of 1017.64 and 319.85, were tested against An. pharoensis different immature stages. Different concentrations of each photosensitizer were prepared using distilled water for the application. Sunlight was used as a light source for the activation of tested photosensitizers. Incubation time was detected according to the method described by El-Mehdawy et al.14.

Twenty-five individuals of each immature stage were deprived of food for six hours and then placed in 300 ml beakers containing 250 ml of different concentrations from each photosensitizer. Then, larval stages were allowed to feed on a small piece of bread for six hours in the dark, and subsequently tested stages were washed extensively to remove the excess photosensitizers and transferred into 200 ml of clean distilled water for the irradiation process. Control groups represented in different concentrations from all tested photosensitizers in the dark. The irradiation process was carried out using sunlight for 20 min. From 12.00 to 12.20 am along with control groups (photosensitizers’ free) to assess the impact of sunlight alone on immature stages. Mortality was recorded right after radiation and after 24 and 48 h. Three replicates of each test were usually used14,15.

Enzymatic measurements

AChE and GST are key biomarkers in toxicological studies. AChE is used to assess neurotoxic effects, while GST helps evaluate detoxification and oxidative stress. Together, they provide insights into the physiological effects of photosensitizers, making them essential for understanding their environmental and biological impacts. For the quantification of AChE and GST, 10 ml solutions of 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.5 (KH2PO4 - NaOH), incorporating 1% Triton X-100, 1% ethanol, and 1% Triton X-100, respectively, were utilized to homogenize three batches of the specified immature stage (derived from each assessed LC50). The Hereaeus Labofuge 400R, manufactured by Kendro Laboratory Products GmbH, Germany, was utilized to centrifuge the homogenates for 60 min at 4 °C and 15,000 x g. The resulting supernatant underwent an in vitro Ache (U/L) inhibition experiment without additional purification16. The GST activity (U/g tissue) was assessed using spectrophotometric measurements of supernatant aliquots, following the methodology outlined in the accompanying brochure for spectrophotometric testing17.

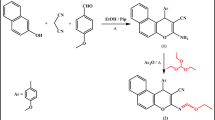

Molecular docking test

To study the binding mechanism and interactions between the two complexes and the AChE enzyme (PDB ID: 6xyu), molecular docking studies were performed using MOE 2015 software. The 3D models of AChE were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 6xyu) at http://www.rcsb.org.pdb. The 3D structures of the ligands and the most potent complexes were created using Chem Draws 18.0 and stored as MDL molfiles. The greatest score went to the chemical that had the lowest binding affinity value.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS (Version 22) and Minitab (Version 14) statistical software. The normality of data distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. For non-normally distributed data, Arcsine square root transformation was applied to standardize mortality percentages. Probit analysis was conducted to determine the LC50 and LC90 values along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each photosensitizer. One-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, was used to compare the mortality rates and enzymatic activities among different treatment groups. A Chi-square (χ²) test was applied to assess significant variations in mortality between treatment and control groups. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and all experiments were conducted in triplicates to ensure reproducibility. Data visualization was performed using R Studio (Version 2022.02.4) to generate graphs and statistical plots.

Results

Anopheles pharoensis has been genetically characterized using the partial sequencing of COI. The recently acquired sequence has been deposited in the gene bank and assigned the accession number PQ346929 (Fig. 1).

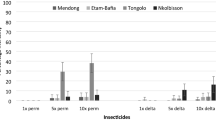

Mortality rates rise significantly with higher concentrations and prolonged exposure. Notably, at the highest doses, both photosensitizers induce 100.0% mortality in first-instar larvae within 24 h, indicating their strong biocidal properties. This high level of efficacy is maintained through the subsequent larval stages, although a slight decline in mortality is observed as the concentration decreases. At the pupal stage, both photosensitizers remain effective, but higher concentrations are necessary to achieve sustained mortality. Specifically, rose Bengal achieves a peak mortality rate of 93.33%, while methylene blue reaches 100.0% mortality at its highest concentrations within 48 h (Table 1 & Fig. 2).

The study clearly demonstrates a progressive increase in the LC50 values for rose bengal from larvae I to pupae, starting at 1.50 ppm (24 h) and 1.34 ppm (48 h) for first-instar larvae, and peaking at 3.83 ppm (24 h) and 3.12 ppm (48 h) for pupae. This upward trend suggests a reduced sensitivity of Anopheles pharoensis to rose bengal as the organism matures, requiring higher concentrations to achieve the same mortality rate in later developmental stages. Similarly, methylene blue follows a comparable pattern, with the lowest LC50 values recorded for larvae I at 1.14 ppm (24 h) and 0.90 ppm (48 h), steadily increasing through the developmental stages and reaching a peak for pupae at 2.91 ppm (24 h) and 2.51 ppm (48 h). Based on these findings, methylene blue appears to be more effective than rose bengal in terms of its overall toxicity across all stages. (Table 2).

For rose bengal, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity progressively increases from first-instar larvae to pupae, suggesting either a compensatory mechanism to counteract the photosensitizer’s effects or a stage-specific sensitivity to enzymatic activity. Specifically, AChE activity starts at 4.86 ± 0.07 in larvae I and peaks at 6.21 ± 0.17 in pupae after 24 h. A similar trend is observed for glutathione S-transferase (GST), with activity rising from 0.53 ± 0.02 in larvae I to 1.24 ± 0.06 in pupae, indicating a higher detoxification effort in later stages.

Methylene blue induces a comparable response, with both AChE and GST activity increasing from early larval stages to pupae. AChE activity rises from 4.64 ± 0.07 in larvae I to 5.90 ± 0.07 in pupae after 24 h, while GST activity increases from 0.67 ± 0.04 to 1.32 ± 0.04, respectively. This progressive rise suggests that as the mosquito matures, its enzymatic systems become more efficient at mitigating the oxidative stress or neurotoxic effects induced by methylene blue. Importantly, both photosensitizers cause significant differences (P < 0.05) when compared to the control groups, with treated groups exhibiting higher enzyme activities than those observed in the controls (Table 3 & Fig. 3).

Molecular docking was performed on both methylene blue and rose Bengal, utilizing the target molecules against AChE (PDB ID: 6xyu) via MOE 2015. The energy scores of the molecules (Table 4) were ascertained to be -7.4948 and − 6.9603 kcal/mol for the Methylene blue and Rose Bengal complexes, respectively, surpassing the control ligand (9-(3-Iodobenzylamino)-1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroacridine) at -6.5522 kcal/mol. The intensity of the contact correlates positively with the magnitude of the negative binding energy. The interaction occurred in the sequence of methylene blue followed by rose Bengal complexes. These results align with experiments on insecticidal activity. Figures (4) illustrates the comprehensive bonding interactions of the pertinent amino acid residues in the AChE (PDB ID: 6xyu) with the docked molecules.

Assessment of method greenness

The integration of green chemistry principles represents a significant advancement in promoting sustainability. The Complex GAPI framework has emerged recently as a critical tool for assessing the greenness of methods, which evaluates multiple dimensions of sustainability, including solvent use, waste generation, energy consumption and method efficiency. This method is evaluated as eco-friendly and environmentally sustainable based on the Complex GAPI metric as shown in Figure 5.

Discussion

Photosensitizing agents activated by sunlight attracted more attention as a new generation of highly efficient and environmentally safe insecticide due to its rapid photo degradation in the visible light18. The present result showed that Anopheles Pharoensis, in different immature stages, were highly sensitive to the tested photosensitizers rose bengal and methylene blue, with 20 min. of sun light irradiation. Methylene blue exhibited privileged activity against Anopheles pharoensis different immature stages than rose Bengal.

Results revealed also that for photosensitizers to be active, an exposure to a visible source of light must happen, which takes place in this study using natural sunlight; this comes along with the recommendation by Khater and Hendawy19 of using sunlight instead of a light source. Methylene blue can be photoactivated with light sources of a range 630–700 nm, while light sources ranging from 380 to 520 nm are used to trigger the photosensitization reaction of rose bengal; both light sources are in the visible spectrum of sunlight. The previous photosensitizers introduce phototoxic effects by singlet oxygen (1O2) generation through a Type-II mechanism (excited triplet state photosensitiser (3Psen*) directly reacts with ground state triplet molecular oxygen (3O2), which is chemically reactive due to the presence of unpaired valence electrons20. These highly cytotoxic singlet oxygen molecules initiate multisite attacks against the intracellular proteins and cellular membranes in cells21. Singlet oxygen (1O2) is highly activated form of oxygen, it is not as stable as the ground state oxygen and will change back quickly (less than 0.04 microseconds) but in that time it will have affected its surrounding molecules by transferring its excitation energy to them and then returns to the ground state22.

The results revealed that the activity of tested photosensitizers is coupled with previous results recorded by Dondji et al.23, where different photosensitizers showed lethal effects to Aedes aegypti, An. Stephensi and Culex quinquefasciatus 4th larval instar, depending on the presence of light; however, rose bengal seemed to be more efficient at even lower concentrations than other photosensitizers against Ae. aegypti larvae, Azizullah et al.24 who recorded that chlorophyll derivatives, natural photosensitizers, can effectively be used against Ae. aegypti larvae, de Souza et al.25, where porphyrin (Photogem) in the presence of sunlight and fluorescent lamp recorded about 100.0% mortality in Ae. aegypti 2nd larval instar after 24 h, El-Shourbagy et al.26, where rose Bengal was the most effective dye against Cu. pipiens 4th larval instar followed by phloxine B, then rhodamine B, and El-Mehdawy et al.14, where rose bengal recorded LC50 and LC90 of 1.07, 1.19, 1.35, 1.65 µM, and 3.88, 3.98, 4.19, 4.51 µM against Cu. pipiens third larval instar, while methylene blue recorded LC50 and LC90 of 2.70, 2.79, 2.99, 3.08 µM and 4.82, 4.90, 5.04, 5.22 µM, respectively.

On the other hand, the results showed an enzymatic response to both photosensitizers depending on the targeted stage. A depression in the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) level in An. pharoensis immature stages as compared with untreated groups was recorded. For rose bengal, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity increased progressively for pupae at 24 h. As a biomarker of exposure to certain classes of pollutants, AChE activity measurements have become commonplace27. In addition, an elevated glutathione-S-transferase (GST) level in The immature stages of An. Pharoensis were recorded by testing the photosensitizers in extracts as compared with the control. The GST activity levels rose in larvae I than pupae stage in the same period. Biotransformation of foreign chemicals, drug metabolism, and protection from oxidative damage are all aided by GST28.

Molecular docking was performed for further evaluation of the role of both methylene blue and rose Bengal, which were investigated by applying the target molecules against AChE (PDB ID: 6xyu) through MOE 2015 apps. The observed results suggested that the stronger the contact and the greater the negative binding energy, the accurate the molecular docking analyses29,30. So, molecular docking validation can help in identifying potential photosensitizer agents’ targets for mosquito management. Molecular docking studies suggested that the acetylcholine receptor (AChR), Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) on Aedes aegypti mosquito larvae were potential targets of compounds containing 2-methyl-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-4-one heterocycle and were supported by bioactivity mechanisms31. Also, Mansour et al.32 used molecular docking to control the 3rd and 4th instars of Culex pipiens larvae using four bacterial strains and confirmed the role of the produced metabolites as larvicidal agents and Acetylcholine esterase inhibition. According to Ghaffar et al.33, the selected proteins after extensive silico molecular docking analyses had the potential to be an effective candidate for affecting the mortality of the larvae of Tribolium castaneum.

Conclusion

This study provides significant insights into the efficacy of rose Bengal and methylene blue as biocidal agents against Anopheles pharoensis at various developmental stages. Both photosensitizers exhibited strong mortality rates, particularly at higher concentrations, with methylene blue showing superior toxicity across all stages compared to rose Bengal. The study also highlighted the progressive enzymatic responses, with both acetylcholinesterase and glutathione S-transferase activities increasing as the larvae matured, suggesting a compensatory detoxification mechanism. Molecular docking further confirmed the strong binding affinity of both photosensitizers to acetylcholinesterase, supporting their potential as effective control agents for mosquito populations. These findings underscore the promising application of photosensitizers in integrated pest management strategies for combating Anopheles pharoensis and possibly other mosquito vectors.

Data availability

The newly obtained sequence of Anopheles pharoensis has been bank-it to gene bank [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/] and given accession number (PQ346929).

References

Lemine, A. M. M. et al. Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Mauritania: a review of their biodiversity, distribution and medical importance. Parasit. Vectors. 10, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-1978-y (2017).

World Health Organization, WHO. World malaria report 2021.Geneva: Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. (2021). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/350147

Shehata, A. Z. I., Labib, R. M. & Abdel-Samad, M. R. K. Insecticidal activity and phytochemical analysis of Pyrus communis L. extracts against malarial vector, Anopheles pharoensis Theobald, 1901 (Diptera: Culicidae). Pol. J. Entomol. 90 (4), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0015.6329 (2021).

Tapondjoua, A. L., Adler, C., Fontem, D. A., Bouda, H. & Reichmuth, C. Bioactivities of cymol and essential oils of Cupressus sempervirens and Eucalyptus saligna against Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky and Tribolium confusum du Val. J. Stored Prod. Res. 41 (1), 91–102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jspr.2004.01.004 (2005).

Shehata, A. Z., El-Sheikh, T. M., Shaapan, R. M., Abdel-Shafy, S. & Alanazi, A. D. Ovicidal and latent effects of Pulicaria jaubertii (asteraceae) leaf extracts on Aedes aegypti. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 36 (3), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.2987/20-6952.1 (2020).

Ben Amor, T. & Jori, G. Sunlight-activated insecticides: historical background and mechanisms of phototoxic activity. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 30 (10), 915–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0965-1748(00)00072-2 (2000).

Moreno, D. S., Celedonio, H., Mangan, R. L., Zavala, J. L. & Montoya, P. Field evaluation of a phototoxic dye, phloxine B, against three species of fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 94, 1427–1429. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493-94.6.1419 (2001).

Saini, R., Lee, N. V., Liu, K. Y. & Poh, C. F. Prospects in the application of photodynamic therapy in oral cancer and premalignant lesions. Cancers (Basel). 8 (9), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fcancers8090083 (2016).

Swartling, J. et al. System for interstitial photodynamic therapy with online dosimetry: first clinical experiences of prostate cancer. J. Biomed. Opt. 15 (5), 058003. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.3495720 (2010).

Swartling, J. et al. Online dosimetry for temoporfin-mediated interstitial photodynamic therapy using the canine prostate as model. J. Biomed. Opt. 21 (2), 28002. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.jbo.21.2.028002 (2016).

Armenta, S., Garrigues, S. & De La Guardia Miguel. Green analytical chemistry. TRAC Trends Anal. Chem. 27 (6), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2008.05.003 (2008).

PŁOTKA-WASYLKA, J., WOJNOWSKI & Wojciech Complementary green analytical procedure index (ComplexGAPI) and software. Green Chem. 23 (21), 8657–8665. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1GC02318G (2021).

Hassanain, N. A. E. H. et al. Comparison between insecticidal activity of Lantana camara extract and its synthesized nanoparticles against Anopheline mosquitoes. Pak J. Biol. Sci. 22 (7), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2019.327.334 (2019).

El-Mehdawy, A. A., Koriem, M., Amin, R. M., El-Naggar, H. A. & Shehata, A. Z. I. The photosensitizing activity of different photosensitizers irradiated with sunlight against aquatic larvae of Culex pipiens L. (Diptera: Culicidae). Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 25 (5), 661–670. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejabf.2021.205672 (2021).

World Health Organization, WHO. Report of the WHO Informal Consultation on the Evaluation on the Testing of Insecticides. CTD/WHO PES/IC/96.169 (WHO, 1996). https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/65962

da Silva Rosa, J. J., Cerqueira, J. A., Risso, W. E. & Martinez, C. B. D. R. Multiple biomarker responses in Aegla Castro exposed to Copper: A laboratory approach. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 87 (3), 253–269 (2024).

El-Tabakh, M. A. et al. UPLC/ESI/MS profiling of red algae Galaxaura rugosa extracts and its activity against malaria mosquito vector, Anopheles pharoensis, with reference to Danio rerio and Daphnia magna as bioindicators. Malar. J. 22 (1), 368 (2023).

Yones, M. S. et al. Evaluation of some photosensitizers against the cotton leaf worm, Spodoptera littoralis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in relation to spectral and thermal reflectance. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 30603 (2024).

Khater, H. F. & Hendawy, N. I. Photoxicity of Rose Bengal against the camel tick, Hyalomma dromedarii. Inter J. Vet. Sci. 3 (2), 78–86 (2014).

Chen, J. et al. New technology for deep light distribution in tissue for phototherapy. Cancer J. 8 (2), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130404-200203000-00009 (2002).

Zhuo, J. Photoactive chemicals for antimicrobial textiles. In Antimicrobial Textiles (197–223). Woodhead Publishing. (2016).

Balin, A. K. & Vilenchik, M. Oxidative damage. Encyclopedia of gerontology. (Second Edition). 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-370870-2/00144-X (2007).

Dondji, B. et al. Assessment of laboratory and field assays of sunlight-induced killing of mosquito larvae by photosensitizers. J. Med. Entomol. 42 (4), 652–656. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/42.4.652 (2005).

Azizullah, A. et al. Chlorophyll derivatives can be an efficient weapon in the fight against dengue. Parasitolo Res. 113 (12), 4321–4326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-014-4175-3 (2014).

de Souza, L. M. et al. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy against larvae of Aedes aegypti: Confocal Microscopy and Fluorescence-Lifetime Imaging. Proceedings of SPIE, Bellingham: International Society for Optical Engineering -SPIE 8947 1–9. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2040420

El- Shourbagy, N. M., Hussein, M. A., Abu El- Dahab, F. F., El- Monairy, O. M. & El-Barky, N. M. Photosensitizing effects of certain Xanthene dyes on Culex pipiens larvae (Diptera- Culicidae). Int. J. Mosq. Res. 5 (6), 51–57 (2018). https://www.dipterajournal.com/pdf/2018/vol5issue6/PartA/5-5-27-579.pdf

Fu, H. et al. Acetylcholinesterase is a potential biomarker for a broad spectrum of organic environmental pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52 (15), 8065–8074 (2018).

Orhan, H., Karakuş, F. & Ergüç, A. Mitochondrial biotransformation of drugs and other xenobiotics. Curr. Drug Metab. 22 (8), 657–669 (2021).

Sehgal, S. A. Pharmacoinformatics and molecular Docking studies reveal potential novel proline dehydrogenase (PRODH) compounds for schizophrenia Inhibition. Med. Chem. Res. 26, 314–326 (2017a).

Sehgal, S. A. Pharmacoinformatics, adaptive evolution, and Elucidation of six novel compounds for schizophrenia treatment by targeting DAOA (G72) isoforms. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017 (1), 5925714 (2017b).

Nguyen, H. H. et al. Potential for Aedes aegypti larval control and environmental friendliness of the compounds containing 2-Methyl-3, 4-dihydroquinazolin-4-one heterocycle. ACS Omega. 8 (28), 25048–25058 (2023).

Mansour, T. et al. Larvicidal potential, toxicological assessment, and molecular Docking studies of four Egyptian bacterial strains against Culex pipiens L. (Diptera: Culicidae). Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 17230 (2023).

Ghaffar, A. et al. Molecular docking analyses of CYP450 monooxygenases of Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) reveal synergism of Quercetin with Paraoxon and tetraethyl pyrophosphate: in vivo and in Silico studies. Toxicol. Res. 9 (3), 212–221 (2020).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Z.I.S.; M.A.M.E.T. and A.A.E. led the study’s design and supervision while revising the manuscript. A.Z.I.S. and M.A.M.E.T. played key roles in conducting experiments and data analysis. L.A.A.E.K. handled the literature review and drafting of the manuscript. A.M.S. and A.N.G.A. assisted with statistical analysis and manuscript revisions. N.A.B. supported the manuscript’s initial draft and submission. H.F.A. was responsible for project administration and funding acquisition. M.A.M.E.T. provided resources and contributed to supervision and final editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical consideration

The study was carried out according to the guidelines of the declaration of Benha University and approved by the Faculty of Science Ethics Committee of Benha University (Code: BUFS-REC-2024-268Ent).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shehata, A.Z.I., El-Mehdawy, A.A., Mahmoud, M.A. et al. Greenness assessment and phototoxicity of rose bengal and methylene blue on immature aquatic stages of malaria vector Anopheles pharoensis. Sci Rep 15, 18324 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03519-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03519-1