Abstract

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a large group of organic pollutants composed of two or more benzene rings. PAHs have attracted widespread attention due to their highly carcinogenic and mutagenic properties in humans. One of the ways PAHs enter the body is through the oral route. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the risk of PAHs through the oral route in the study area. In this research, which was a descriptive-analytical study, 150 samples of kebabs (grilled chicken, leaf kebab, and shredded kebab) were collected from Zahedan city. After preparing the samples to determine the concentration of 16 PAHs, the samples were analyzed using gas chromatography. A Mass spectrometer was used, and then, using the relevant formulas, the health risk caused by these compounds was assessed. Hazard Quotient (HQ) and non-carcinogenic risk index (HI) based on the type of oven and the type of meat were less than one in both children and adults. On the other hand, the risk of carcinogenicity in charcoal ovens was higher than in gas ovens. Also, the risk of carcinogenicity in red meat was higher than in white meat. The total risk in both groups (children and adults) was negligible (< 10–6). Since the health risk in charcoal ovens is higher than gas ovens, therefore, less use of charcoal ovens should be cultured for the general public. Also, according to the findings of this study, the health risk of consuming red meat is higher than white meat. Therefore, it is recommended to reduce the consumption of red meat compared to white meat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a group of complex organic compounds composed of two or more fused benzene rings. These compounds are ubiquitous environmental contaminants that are produced primarily through the incomplete combustion of organic materials such as wood, coal, oil, and biomass, as well as during industrial processes1. PAHs are highly lipophilic and persistent in the environment, meaning they tend to accumulate in fatty tissues and remain in the ecosystem for extended periods. Due to their toxicological properties—including carcinogenic, mutagenic, and genotoxic effects—PAHs represent a significant public health concern2,3.

PAHs can be categorized into light and heavy PAHs based on the number of benzene rings they contain. Light PAHs, containing up to four benzene rings, are generally less toxic, whereas heavy PAHs, with five or more benzene rings, tend to exhibit stronger carcinogenic properties4,5. The potential health risks posed by PAHs have led to their classification as priority pollutants by numerous regulatory agencies, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), which has identified 16 PAHs for monitoring6,7.

While PAHs are found in the air, water, and soil, food consumption is the primary route of exposure for non-smokers and non-occupationally exposed individuals8,9. Among various food items, meat, especially when cooked using high-temperature methods such as grilling, barbecuing, and smoking—are a significant source of PAHs in the human diet. These cooking methods involve the thermal decomposition (pyrolysis) or incomplete combustion of fats and proteins, which promotes the formation of PAHs. Grilled meat, particularly, has been identified as a major contributor to PAH exposure due to the direct contact of food with flames or hot surfaces, which can result in the formation of both volatile and non-volatile PAHs that adhere to the food surface10,11.

Grilling meat involves intense heat and, in many cases, the use of charcoal, wood, or gas as fuel, all of which can generate significant levels of PAHs. The fat content of the meat and the cooking temperature play crucial roles in determining the concentration of PAHs in grilled foodstuffs. Fats and juices dripping from meat during grilling may burn, creating smoke that deposits PAHs back onto the surface of the food. The duration of grilling, the proximity of the food to the heat source, and the type of fuel used all influence PAH formation12.

Recent studies have confirmed that PAH concentrations in grilled foods vary significantly depending on these factors. For example, meat cooked over charcoal tends to have higher levels of PAHs than meat cooked with gas or in an oven, as the latter methods typically involve less direct exposure to the flames13. Additionally, different types of meat, such as beef, chicken, and fish, may exhibit varying PAH levels due to their differing fat content and protein structure14.

Among the most concerning PAHs is benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), which has been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a Group 1 carcinogen, indicating that it is carcinogenic to humans15. Studies have linked the consumption of foods with high levels of PAHs, including grilled meats, to an increased risk of developing various cancers, such as breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers16,17. Therefore, it is critical to assess the extent of PAH contamination in grilled foods, especially in cultures where grilling is a popular cooking method.

While much of the research on PAHs has focused on their presence in air pollution and tobacco smoke, there remains a significant gap in understanding the levels of PAHs in commonly consumed grilled foods, such as kebabs, particularly in regions like Iran, where grilling meat is an integral part of the cuisine. The levels of 16 priority PAHs in grilled meats and the potential health risks posed to both children and adults are not well documented. This study seeks to address this gap by examining the concentrations of PAHs in various kebab types, such as grilled chicken, leaf kebab, and shredded kebab, and evaluating the associated carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks. Specifically, the study will explore how cooking methods (charcoal grilling, gas grilling, and oven grilling) and meat types affect PAH levels, offering insight into safer cooking practices and potential interventions to reduce PAH exposure.

Given the growing public health concerns associated with PAH contamination in food, this study aims to provide critical data that could influence food safety regulations and public health recommendations. By quantifying PAH levels in popular grilled dishes and assessing the associated health risks, the research will contribute valuable information to the ongoing dialogue on foodborne contaminants and help promote safer cooking practices worldwide (Table 1)3. Evidence suggests that antioxidants significantly decrease PAH concentrations in food. As a result, incorporating the optimal antioxidant mix in food formulation can successfully curb PAH development. Moreover, antioxidants have been shown to mitigate PAH-related toxicity in humans18

Carcinogenic and toxicological effects of PAHs

The presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in food, particularly grilled meat, raises significant concerns due to their well-documented toxicological effects, many of which are carcinogenic in nature. The dangers associated with PAH exposure are especially alarming considering that grilled meats—beloved in many cultures for their taste and nutritional value—are a primary source of PAHs in the human diet. PAHs, especially those with higher molecular weights like benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), are classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as Group 1 carcinogens, meaning they are known to cause cancer in humans19.

The carcinogenicity of PAHs stems primarily from their ability to form DNA Adults. Once PAHs enter the body, they undergo metabolic activation by cytochrome P450 enzymes into highly reactive intermediates. These intermediates can bind to cellular DNA, causing mutations that may lead to uncontrolled cell growth and, ultimately, cancer. Studies have shown a strong correlation between PAH exposure and the increased incidence of cancers, particularly those of the lung, skin, bladder, and gastrointestinal tract20,21. B[a]P, one of the most common PAHs found in grilled foods, is associated with an elevated risk of lung cancer and gastrointestinal cancers, including colorectal cancer, due to its potent mutagenic effects.

Beyond carcinogenicity, PAHs also have other toxicological impacts that can adversely affect human health. These compounds are known to have mutagenic and genotoxic properties, meaning they can cause mutations in the genetic material of cells and induce damage to DNA, chromosomes, and the overall genetic structure of cells1. Such genetic damage can lead to long-term health problems, including birth defects, neurological disorders, and immunosuppression. PAHs also exhibit endocrine-disrupting effects, which can interfere with hormone regulation, potentially leading to developmental and reproductive issues22.

In addition to their direct carcinogenic and genotoxic effects, PAHs can have chronic toxicity when exposure occurs over extended periods. Chronic exposure to PAHs, even at low levels, has been linked to respiratory issues, cardiovascular diseases, and liver toxicity23. Given that many people consume grilled meat regularly, especially in countries where grilling is a culinary tradition, the cumulative exposure to PAHs from these foods can become a significant public health concern.

The impact of grilled meat consumption

Despite the known health risks, grilled foods—particularly meats such as kebabs, steaks, and sausages—are widely enjoyed for their unique flavor, aroma, and texture. In many cultures, including in Iran, grilled meat dishes like kebab are not only a source of sustenance but also an integral part of social gatherings and traditional cuisines. The enjoyment of these foods presents a dilemma, as the cooking methods that contribute to the formation of PAHs also enhance the appeal of grilled dishes. The high temperatures involved in grilling, as well as the fat content in meats, increase the likelihood of PAH formation through processes like pyrolysis and incomplete combustion.

While these foods are delicious, the health implications of regularly consuming grilled meats with high PAH content cannot be overlooked. Epidemiological studies have shown that diets high in charred and grilled foods are associated with an elevated risk of several types of cancer. For instance, a study by Carrabs et al.24 found that a higher intake of grilled meats, particularly red meat, was linked to increased rates of colorectal cancer24. Similarly, research has suggested that exposure to PAHs through grilled meat may increase the risk of prostate cancer, breast cancer, and even pancreatic cancer, especially in individuals who have high levels of PAH exposure due to frequent consumption of grilled or smoked foods1016.

A public health concern

The toxicological effects of PAHs, combined with the widespread consumption of grilled meats, highlight an urgent need for public health interventions and consumer awareness regarding the risks of PAH exposure from food. While occasional consumption of grilled foods may not pose an immediate danger, chronic and excessive intake of PAH-contaminated foods, especially from grilling methods involving direct contact with flames (e.g., charcoal grilling), can contribute significantly to long-term health risks. For vulnerable populations, such as children and individuals with compromised immune systems, the toxic effects of PAHs can be even more pronounced.

Given the growing body of evidence linking PAH exposure to a variety of health problems, it is essential to quantify the levels of PAHs in popular grilled foods to better assess the potential health risks associated with their consumption. Understanding the factors that influence PAH formation—such as cooking methods, the type of meat used, and cooking duration—can help mitigate these risks by providing consumers and food producers with guidelines for safer cooking practices.

Several epidemiological studies have indeed established a strong connection between the consumption of grilled meats, particularly those cooked at high temperatures, and the increased risk of various cancers and chronic diseases due to PAH exposure. For instance:

Carrabs et al.24 conducted a cohort study that found higher consumption of grilled meats, particularly red meats, was associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. The study attributed this increased risk to the high levels of PAHs, such as benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), which are present in grilled meats24

Demirok and Kolsarıcı (2014) also investigated the relationship between PAH exposure from grilled meats and the risk of breast and prostate cancers. Their findings confirmed that frequent consumption of grilled meats contributed to higher PAH exposure, significantly increasing the risk of these cancers10,16.

Alomirah et al. provided additional epidemiological evidence linking PAH intake from grilled meats to various types of cancers. The study suggested that individuals who consume grilled or smoked foods on a regular basis have higher concentrations of PAHs in their bodies, which is correlated with an elevated risk of developing several forms of cancer, including gastrointestinal and breast cancers16.

Smith et al. (2020) explored the long-term health effects of PAH exposure through diet and found that chronic exposure to PAHs, particularly from high-temperature cooking methods like grilling, is associated with respiratory diseases, cardiovascular conditions, and liver toxicity. These chronic conditions are a consequence of repeated PAH accumulation in the body25.

These studies provide a solid epidemiological foundation for understanding the public health risks associated with PAH exposure from grilled meats. We have now included these references in the revised manuscript to support our discussion of the health risks tied to PAH contamination in grilled foods. These studies not only bolster the relevance of our research but also highlight the pressing need to assess and mitigate PAH exposure in widely consumed grilled foods, such as kebabs, which are the focus of our study.

PAHs in grilled meats and assessed the associated health risks. Research has consistently shown that high-temperature cooking methods, such as grilling, lead to the formation of PAHs, particularly in meats with high fat content.

Global studies on PAHs in grilled meats

Janoszka et al. (2004) reported that grilled meats, particularly beef and chicken, contain significantly higher levels of PAHs when cooked over charcoal compared to other cooking methods like gas grilling or oven roasting. The study found that the PAH concentrations in grilled meats ranged from 14 to 132 ng/g, depending on the type of meat and the cooking method12.

Demirok and Kolsarıcı (2014) found similar results, with PAH levels being significantly elevated in grilled meats, especially when charcoal was used as the fuel. Their study identified the presence of carcinogenic PAHs such as benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P) in beef and chicken, which were linked to an increased cancer risk10.

Kiani et al. (2021) observed that meat grilled over charcoal exhibited higher PAH concentrations compared to meat grilled using gas or in an oven, highlighting the influence of cooking methods on PAH formation13.

Local studies on PAHs in grilled meats

Locally, especially in regions like Iran, where grilling is a staple cooking method, studies have shown that grilled meat dishes such as kebabs contain considerable levels of PAHs. A study by Farhadian et al. (2010) on various grilled meats found that the levels of B[a]P in grilled dishes ranged from 4.65 to 132 ng/g, depending on the meat type and grilling method. The study found that beef kebab, for example, had higher PAH levels when grilled over charcoal, which was associated with increased risks of colorectal cancer5.

Health risks associated with PAHs in grilled meats

Risk assessment techniques are critical tools for evaluating how environmental and dietary exposures impact human health26,27,28,29. They provide a structured, scientific approach to:

1. Identifying Hazards

-

Environmental Exposures: Detect harmful pollutants (e.g., PAHs, heavy metals, pesticides) in air, water, soil, and food26,27,30.

-

Nutritional Factors: Assess contaminants (e.g., acrylamide in fried foods) or nutrient deficiencies/excesses (e.g., vitamin D, sodium) linked to disease31.

2. Quantifying exposure levels

-

Estimate how much of a hazardous substance enters the body (via ingestion, inhalation, or skin contact).

-

Example: Measuring PAH intake from grilled meats based on portion size, cooking method, and frequency of consumption30.

3. Evaluating health risks

-

Carcinogenic Risk: Calculate lifetime cancer probability (e.g., from benzo[a]pyrene in smoked foods).

-

Non-Carcinogenic Risk: Determine hazard quotients (HQ) for chronic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular effects from heavy metals).

-

–Sensitive Populations: Identify higher risks for children, pregnant women, or immunocompromised groups27,29.

4. Guiding public health interventions

-

Policy Making: Set safe limits for contaminants in food/water (e.g., WHO/EPA standards).

-

Consumer Awareness: Advise safer cooking practices (e.g., using marinades to reduce PAHs) or dietary choices (e.g., limiting processed meats)26,29,30.

-

–Industry Regulations: Improve food production/processing methods to minimize toxin formation.

5. Cost-effective prevention

- Early risk detection reduces healthcare burdens by preventing chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, diabetes) linked to environmental/dietary factors26,29,30.

As detailed in this manuscript, the health risks associated with PAH exposure, particularly through grilled meats, are substantial. PAHs, especially those like benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), are known carcinogens. Epidemiological studies have linked the consumption of grilled meats with an increased risk of cancers such as colorectal, breast, and prostate cancers10,17 (Demirok and Kolsarıcı 2014). Chronic exposure to low levels of PAHs, even in the absence of heavy consumption, has also been associated with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases25.

This study has now expanded the discussion to incorporate these findings, as well as the factors influencing PAH formation during grilling, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the risks involved and the potential steps that could be taken to reduce exposure.

While there is considerable literature on the presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in grilled meats globally, there are still significant gaps in understanding both the extent of PAH contamination in commonly consumed grilled foods and the associated health risks. Some key areas where research is lacking or insufficient include:

Limited data on PAH levels in popular grilled meats in specific regions

Much of the existing research on PAHs in grilled meats has focused on Western countries, particularly the United States and Europe. However, there is a notable lack of data from regions where grilling is a predominant cooking method, such as in Middle Eastern countries (e.g., Iran), South Asia, and Africa. In these regions, grilled meats like kebabs, satays, and barbecued meats are an integral part of traditional cuisine. Yet, the levels of PAHs in these foods and their associated health risks are poorly documented. Our study addresses this gap by specifically examining the levels of PAHs in kebabs and other popular grilled meats in Iran, a country where grilling is culturally and socially significant.

Variation in PAH concentrations based on meat type and grilling method

Although studies have reported PAH levels in grilled meat, few have comprehensively examined the impact of different cooking methods (charcoal, gas, and oven grilling) on PAH concentrations across a range of meat types (e.g., chicken, beef, fish). Our study is one of the few to investigate how factors like cooking duration, proximity to heat, and fat content affect PAH formation in grilled kebabs, a food widely consumed in Middle Eastern and South Asian countries. The variety of meats used in grilling (beef, chicken, fish, etc.) presents a gap in knowledge regarding which types of meat pose the greatest health risks based on their PAH content.

Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks

Although numerous studies have explored the carcinogenic effects of PAHs, especially benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), there remains a significant gap in research concerning the non-carcinogenic health risks of PAH exposure from grilled foods. For example, the impact of chronic low-level PAH exposure through diet (especially from grilled meats) on respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological health has not been sufficiently studied. This gap is particularly critical for vulnerable populations, such as children, pregnant women, and individuals with pre-existing health conditions, who may be at greater risk from regular PAH exposure. Our study aims to fill this gap by assessing both the carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks associated with PAH levels in grilled kebabs, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the potential health consequences.

Health risk assessment for specific populations.

While some studies have linked high PAH levels in grilled meats to cancer risks, there is a lack of targeted research assessing the health risks for specific populations, such as children, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals. These groups may be more susceptible to the harmful effects of PAH exposure due to differences in metabolism, detoxification capacity, and overall vulnerability to environmental toxins. Our research aims to provide health risk assessments that include both adult and child populations, which will help to identify whether certain groups face disproportionately higher health risks from PAH exposure in grilled foods.

Methods and materials

Sampling and preparation of kebab samples

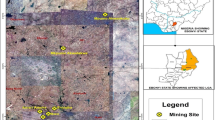

The kebabs used in this study were cooked at traditional kebab supply centers in Zahedan (Research community of kebabs cooked in traditional kebab supply centers in Zahedan that are cooked on the same day that the list of fixed traditional kebab supply centers in Zahedan was prepared from the health center and tried to divide Zahedan city into 4 regions and from each region Randomly, according to the fixed supply centers of traditional kebabs in that area, 150 samples (50 pieces of each type of kebab, which includes chicken kebab, leaf kebab and shredded kebab) were prepared. The geographic location of the sampling area is shown in Fig. 1. The kebabs were prepared using two cooking methods: charcoal grill or charcoal furnace and gas flame. These methods are common in the preparation of kebabs in the region. Once cooked, the kebab samples were immediately collected and packaged in polyethylene bags for transport to the laboratory. The samples included three types of kebabs: chicken kebab, leaf kebab, and shredded kebab, and each type was sampled from different kebab supply centers.

Sample storage

The kebab samples were then cut into 2.5 to 5-cm pieces (bones were removed from the “grilled chicken” kebabs).

After homogenization, the samples were wrapped in vacuum-sealed nylon. The kebab samples were stored at – 80 °C in the dark for more than four weeks to minimize degradation of the PAHs and to ensure that any potential environmental contaminants or light-sensitive reactions did not alter the PAH concentrations. Freezing at this temperature is a common practice to preserve non-volatile compounds such as PAHs. This storage condition helps maintain the integrity of the PAH content until the time of analysis. The four-week storage period was chosen to allow sufficient time for the processing of all samples in batches, with the storage method being in line with standard protocols used in environmental contaminant analysis. We acknowledge that freezing can cause changes in the lipid profile, but this effect is less critical in the context of PAH analysis. This storage procedure has been used in similar studies18, and was conducted according to ethical guidelines for sample handling and preservation.

Chemicals and reagents

The PAH standards used in this study, including Acenaphthene (Alomirah et al.), Acenaphthylene (Ace), Fluorene (F), Phenanthrene (Phe)32, Anthracene (A), Fluoranthene (Fl), Pyrene (P), Benzo[a]anthracene (BaA), Chrysene (Ch), Benzo[b]fluoranthene (BbF), Benzo[k]fluoranthene (BkF), Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP), Indenol[1,2,3-cd]pyrene (IP), Dibenzo[a,h]anthracene (DhA), and Benzo[ghi]perylene (BgP), were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich. Additionally, other chemicals required for this research were procured from either Sigma-Aldrich or Merck.

Extraction method and analysis

The extraction technique used in this research is solid phase extraction (SPME). To 5 g of the homogenized sample, 1 mg of internal standard (biphenyl) was added and associated for 10 min, after which 7.5 ml of a methanol–acetonitrile mixture and 7.5 ml of potassium hydroxide were added, followed by shaking. A few drops of hydrochloric acid were introduced to neutralize the solution. Then, 10 mg of magnetic nanotube carbon adsorbent was added to the mixture and 50 mg of NaCl was added. After mixing with the shaker (Model KS500 Janke and Kunkel, IKA- Labor Technik Germany), the solution was introduced into a vial and then 1 ml of dichloromethane was added after shaking, the mixture was transferred to a clean container and evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas to remove the solvents, leaving the residue for further analysis. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) [Model 7890 B], Agilent (U.S.A) was used to was used to identify and quantify PAH compounds in the samples at ppb levels6. The PAH concentrations in the grilled meats from Health risk calculations related to PAH exposure were performed separately using the relevant formulas in the subsequent risk assessment section.

Validation of methodology

The validation of the analytical methodology employed for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon33 analysis was meticulously executed through a sequence of experimental protocols. The foundational step involved the determination of the linear dynamic range, limit of detection (LOD) for each PAH analyte, grounded on empirical data34. To ascertain the linearity of the method, calibration curves were systematically developed. This was achieved by preparing model solutions, each spiked at five distinct concentration levels, thereby spanning the expected range of PAH concentrations. The calibration curves were delineated by plotting the measured peak areas of the PAH compounds against their known concentrations. Linear regression analysis was then applied to each curve to deduce the slope, y-intercept, and correlation coefficient, thereby quantifying the linear relationship and response consistency of the analytical method. In addition to linearity assessment, the method’s recovery efficiency was rigorously evaluated. The percent recovery for PAH compounds were determined with observed values ranging from 93.2% to more than 99%, indicating the method’s accuracy and reliability of the method in quantifying PAH in sample matrices.

Risk assessment

Health risk is defined as the possibility of harmful effects to human health as an end of environmental contamination35,36,37,38. Among the routes of human exposure to PAHs are inhalation, skin contact, and the oral route through the consumption of contaminated foods. Among these pathways, the consumption of contaminated foods is recognized as the main route of human exposure to PAHs39,40. Health risks caused by many contaminants that enter the human body via different exposure ways are categorized into carcinogenic risk and non-carcinogenic risk. Carcinogenic risk is the incremental option of a person emerging any type of cancer throughout lifetime due to the exposure to specified carcinogens. Non-carcinogenic risk is assessed by comparing the level and duration of exposure to a contaminant against a specified reference dose, which represents a safe exposure level over a defined time period, to determine the likelihood of adverse health effects other than cancer41,29,43. It is shown in Table 2 factors and definitions of risk assessment.

Risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in grilled meats

Health risk assessments related to exposure to PAHs through the consumption of grilled meats in Zahedan were conducted using both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk models. The assessment was performed based on the concentration of individual PAH compounds in the meat samples, as identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS).

Carcinogenic risk assessment

The carcinogenic risk was calculated using the Incremental Lifetime Cancer Risk (ILCR) model, as recommended by the US EPA. The formula for calculating ILCR is as follows:

where ADD is the Average Daily Dose (mg/kg body weight/day), calculated based on the PAH concentration in the meat and the average consumption rate. CSF is the Cancer Slope Factor (mg/kg body weight/day), a factor that characterizes the carcinogenic potency of each PAH compound.

A risk value greater than 1 × 10−6 indicates an increased lifetime cancer risk, while values below this threshold are considered to represent negligible risk.

Non-carcinogenic risk assessment

Non-carcinogenic risk was evaluated using the Hazard Quotient (HQ) approach. The formula for calculating HQ is44:

where ADD is the Average Daily Dose, as defined above. RfD is the Reference Dose (mg/kg body weight/day), which is the threshold below which no adverse non-carcinogenic effects are expected.

An HQ value greater than 1 indicates a potential for adverse health effects, while values less than 1 suggest negligible risk.

Risk characterization

The total health risk from PAH exposure through grilled meat consumption in Zahedan was characterized by integrating both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks. The cumulative health impact of PAH exposure was assessed based on the individual risk levels for each PAH compound, and the overall risk was determined based on the highest risk observed across all compounds35,45.

The results of the risk assessment provide an indication of the potential health risks associated with the consumption of grilled meats contaminated with PAHs. Health authorities should consider the cumulative risks identified in this study when issuing food safety guidelines46,47,48.

Results and discussion

Statistical evaluation of PAH concentrations in different kebab types

The primary objective of this study was to analyze the concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in different types of traditional kebabs (chicken, leaf, and shredded) grilled at various supply centers in Zahedan. A total of 150 kebab samples were analyzed using solid-phase microextraction (SPME) followed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS).

The following analyses were conducted:

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, and range, were calculated for the PAH concentrations in the samples to give an overview of the distribution and central tendency of the data. This helps in understanding the variability in the PAH levels across the different types of kebabs (Khalil et al., 2023; Shamsipour et al., 2023).

Pearson correlation analysis

To investigate the relationships between different PAH compounds, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was computed. This method was used to identify if any significant positive or negative correlations exist between PAH compounds in the grilled meat samples. A correlation matrix was constructed to visualize these relationships49,50.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA was performed to reduce the dimensionality of the data and identify the underlying factors that contribute to the variation in PAH concentrations. By reducing the data into principal components, PCA helped in understanding how different kebab types (chicken, leaf, shredded) vary in their PAH profiles and identifying the key variables responsible for this variation51,52.

Cluster analysis

A hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was employed to group the kebab samples based on similar PAH profiles. This method categorized the samples into clusters to help identify patterns in PAH contamination based on the cooking method or geographical region53,54. This analysis provided insights into whether certain kebab types or regions exhibited higher levels of specific PAHs.

Factor analysis

Factor analysis was used to identify underlying latent variables that could explain the observed variability in PAH concentrations across different kebab types. This method allowed for the reduction of the number of variables by grouping them into factors, facilitating a clearer interpretation of which PAH compounds tend to occur together55,56.

Statistical significance (p-value)

To assess the significance of differences in PAH levels between kebab types, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, followed by post-hoc testing (such as Tukey’s HSD test) to identify which specific kebab types showed significant differences. The p-value for these tests was set at 0.05, with values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant57,58.

Note on p-value: The p-value provides an indication of whether the observed differences are statistically significant. In this study, the p-value was calculated based on the comparison between different kebab types (chicken, leaf, and shredded) and their PAH content. A p-value less than 0.05 suggests that the differences in PAH concentrations between kebab types are unlikely to be due to chance59.

Interpretation of results

The results of these statistical analyses provided a comprehensive understanding of how PAH concentrations vary across different kebab types, cooking methods, and regions. The principal components, clusters, and factors identified in PCA, and cluster analysis helped explain the variation observed in the data, while the correlations between different PAH compounds provided insights into their potential co-occurrence in grilled meats51,52.

By applying these advanced statistical methods (Pearson correlation, PCA, cluster analysis, factor analysis, and ANOVA), the variation in PAH concentrations across different kebab types, cooking methods, and geographical regions was effectively analyzed. The integration of these techniques ensures a more thorough understanding of the data, allowing for more robust conclusions regarding the health risks posed by PAH contamination in grilled meats60,61,62.

This version introduces the use of correlation, factor analysis, PCA, and cluster analysis to explain the variation in PAH levels, making the statistical analysis more transparent and robust. It also clarifies the p-value’s role in determining statistical significance, ensuring the results are properly explained and understood.

PAH concentration levels in grilled meats

The data clearly indicate that charcoal grilling leads to higher PAH levels in kebabs compared to gas grilling, supporting findings from previous studies63,64. The combustion of charcoal produces a wide range of by-products, including PAHs, due to the incomplete combustion of organic matter. This incomplete combustion is known to generate harmful compounds that adhere to the surface of grilled foods, particularly when meat is exposed to direct flame and smoke.

On the other hand, gas grilling, which uses more controlled combustion, results in lower levels of PAH contamination. This supports the hypothesis that gas grilling is a cleaner alternative in terms of both PAH production and health risks. However, it is important to note that gas grills are not entirely free from harmful emissions, and their use does not eliminate the risk of PAH formation, particularly if grilling is done at very high temperatures for extended periods.

The PAH concentrations in the grilled meat samples (chicken kebab, leaf kebab, and shredded kebab) were analyzed for 16 different PAH compounds, which were quantified using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS). The mean concentrations of individual PAHs varied significantly across different kebab types, reflecting differences in cooking methods, meat composition, and the presence of potential contamination sources in the supply chain.

The average concentrations of each PAH compound in the kebab samples were compared using appropriate statistical tests. A one-sample t-test was employed to evaluate whether the measured concentrations of PAHs significantly deviated from established standard reference values. This statistical test was chosen as it tests whether the mean concentration of each compound in the kebab samples was statistically different from the standard value (set according to food safety guidelines or previous studies). The t-statistic and t-critical values were calculated for each PAH compound, and the p-values were examined to determine whether the observed concentrations were significantly different from the reference values.

Statistical significance

For clarity, the one-sample t-test was conducted on each PAH compound to test whether the concentration levels in the kebab samples were statistically higher or lower than the reference standards. The results indicated that several PAH compounds, such as Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) and Benzo[a]anthracene (BaA), had concentrations significantly higher than the standard values, indicating a potential health risk from consuming these grilled meats. The p-values for these compounds were less than 0.05, suggesting that the observed differences were statistically significant65).

The independent t-test was also applied to compare the PAH concentrations between different types of kebabs. While this test was used to evaluate differences between kebab types (e.g., chicken vs. leaf kebab), it is important to note that it does not directly identify the highest mean concentration, which requires more complex analyses (e.g., ANOVA or post-hoc testing)66. The results of the independent t-test confirmed that the PAH concentrations in the different kebab types varied significantly, with chicken kebabs showing consistently higher concentrations of several carcinogenic PAHs compared to leaf kebabs56.

Principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis

Further analysis using principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis was conducted to explore patterns and relationships in the data. PCA revealed that the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) explained over 70% of the variance in PAH concentrations, suggesting that the type of kebab (chicken, leaf, shredded) and the method of grilling are significant factors influencing the variation in PAH contamination levels51.

Cluster analysis was used to group kebab samples based on their PAH profiles. The results showed that kebabs with higher fat content, particularly shredded kebabs, tended to cluster together, indicating higher concentrations of PAHs associated with fat and oil decomposition during the grilling process52. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown that fat-rich foods are more prone to PAH contamination due to the formation of these compounds during high-temperature cooking methods67.

Investigating the effect of meat type on PAHs values

The concentration of PAHs in grilled meats depends on several factors. Meats such as chicken and beef can vary in fat content.

The fat content of food can contribute to the production of PAHs through thermal degradation or polymerization, as well as through various thermal processes that quantitatively affect the formation of PAHs.

The high fat content in foods significantly influences the levels of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs), particularly in cooking methods like grilling. Fat acts as a major precursor for PAH formation, where the cooking process, especially at high temperatures, leads to the chemical decomposition of fat and subsequent PAH generation. This is evident in grilled meats, where the fat dripping onto the heat source produces smoke rich in PAHs, thereby increasing their concentration on the food. Studies, such as the one by Hamidi, have demonstrated a clear correlation between the fat content in foods and the levels of PAHs, with high-fat foods showing higher PAH levels compared to their low-fat counterparts68. In the present study, the total PAHs in the sample of white meat (grilled chicken) with the lowest amount in the gas oven 7.93 μg/kg and charcoal oven 8.86 μg/kg and in the sample of red meat (kebab and leaves) with the highest amount in the oven 10.46 and 11.77 μg/kg gas were observed in 13.13 and 12.91 μg/kg in charcoal furnace. Min et al., Reported that the addition of lipid precursors resulted in a significant increase in PAHs (p < 0.05)69. It is shown in Tables 3 and 4 non-carcinogenic risk assessment based on the type of meat in adults and children.

Afsaneh Farhadian et al. reported that among the 9 most popular grilled meats in Malaysia, the highest total PAHs concentration was 132 ng/g in satay beef and the lowest in grilled chicken was 3.51 ng/g5.

Wanwisa Wongmaneepratip et al. Also reported that the addition of oil could be important in increasing PAH levels in grilled meat products70. A review of similar research showed that if the heat source and other conditions are the same, PAHs change to a significant extent by changing the type of grilled meat. So that the amount of these compounds in red meat barbecue is more than white meat barbecue. According to the United States Department of Agriculture database, the average fat content of mutton is 17%, veal is 5%, and chicken breast is 3.6%, which are mainly saturated fatty acids. The difference in the concentration of PAHs produced in red and white meat grills can be caused by the fat content of the meat, because red meat has more fat than white meat. In this regard, the amount of production of these compounds during grilling of mutton meat is higher than that of veal meat and chicken fillet, respectively71,72. Of course, it should be noted that most of the fat in chicken meat is subcutaneous and is often separated during the process of removing the chicken skin from it, and therefore, chicken fillet is the best meat for grilling due to its low-fat content. But since it is not possible to separate the skin in the chicken wing areas, the fat content of this part of the meat is very high, so that in several studies, the amount of PAHs produced in chicken wing grill was significantly higher than chicken fillet14,73.

Meat fat not only nutritionally increases the intake of calories, saturated fatty acids and increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases in the consumer74, but it is also an important substrate for the production of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds and promoting the pyrolysis process. In the production of heterocyclic aromatic amino compounds75,76. It has been observed in several studies that adding oil to barbecue sauce increases PAHs in barbecued meat, and the higher the percentage of unsaturation in the oil, the higher the production of PAHs70,77.

It is possible that unsaturated oils can be more effective in transferring heat from the surface to the center of the meat and increasing the temperature of the meat due to their lower melting and boiling points. On the other hand, due to the presence of double bonds in their chemical structure, they are highly prone to oxidation at high temperatures, which can be another factor for increasing the production of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds. However, the rate of oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids in meat and oil is completely dependent on the amount of antioxidant compounds present in them. In this regard, it was observed in several studies that placing the meat before grilling in food with antioxidant properties such as saffron, turmeric, garlic, black pepper, curry powder, cloves, cardamom, mustard and epigallo catechin gallate, green tea, It causes a significant reduction in the amount of peroxides, PAHs produced in barbecue70,78,79,80. These antioxidant compounds are not only effective and useful in reducing compounds harmful to health, but in many clinical studies, beneficial therapeutic effects have been observed for them33,81. It is necessary to state that fat does not only cause the production of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds in grilled meat, but the smoke caused by the leakage of fat droplets on the flame is one of the other ways of producing these compounds, which are easily absorbed by other food or It enters the body through inhalation82.

Chicken kebabs, which generally have more fat content than leaf or shredded kebabs, exhibited the highest levels of PAH contamination. This observation aligns with existing literature indicating that fatty foods tend to absorb higher amounts of PAHs due to the lipophilic nature of these compounds83. The molecular size of PAHs may also play a role in their accumulation in fatty tissues. Shredded kebabs, with lower fat content, exhibited comparatively lower levels of PAHs, suggesting that fat content is a significant factor influencing PAH uptake during grilling.

The effect of furnace type on PAHs values

The type of fuel consumed, such as electricity, gas, wood and charcoal, affects the level of PAHs formed. Gas and charcoal flames can induce PAHs in cooked meat68. Alumira et al. showed that grilling meat in a charcoal oven releases significant amounts of PAHs compared to meat grilled in an electric oven16. According to Purcaro et al., Burning carbon produced fewer PAHs than wood84. In the present study, total PAHs were observed in gas furnace 30.16 μg/kg and charcoal furnace 34.9 μg/kg. Mohammad Ishaqi et al. reported that the concentration of PAHs was significant between charcoal and grilled gas samples as well as between different types of meat. The highest and lowest concentrations of PAHs were observed in charcoal grilled chicken wings and gas grilled chicken meat, respectively14. Terzi et al. Also reported that the mean levels of benzo alfa pyrene were 24.2 μg/kg for charcoal-fired meat samples and 5.7 μg/kg for gas-fired meat samples85. It is stated in Tables 5 and 6 non-carcinogenic risk assessment based on the type of furnace in adults and children.

The review of similar articles shows that the amount of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds and heterocyclic aromatic amines in barbecue is completely dependent on important and modifiable factors. The heat source in the barbecue plays a large role in the production of polycyclic hydrocarbon compounds. So that the amount of production of these compounds is significantly reduced by changing the heat source from charcoal and wood to gas5,14,44,77. This observed difference is caused by the type of heat produced in the charcoal and gas flame, so that the charcoal flame produces a higher and drier heat than the gas flame86. In this regard, with the increase in temperature, the concentration of PAHs in barbecue increases significantly87,88. Also, a study that was conducted with the aim of investigating the role of wet and dry heating systems on the concentration of PAHs produced in grilled beef showed that the concentration of PAHs in dry temperature is significantly higher than in wet heat69. Although the origin of many polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds in barbecue is formed directly from the pyrolysis of organic compounds in meat at a temperature above 200 degrees Celsius, the smoke caused by incomplete combustion of fuel is one of the other ways of producing these compounds. These compounds released in the air have a low vapor pressure (10–11 to 8.5 × 10−2 mm Hg) and are easily absorbed by food. Therefore, the increase in the concentration of PAHs as the barbecue approaches the fuel source is not only due to the increase in heat, but it can also be due to the high concentration of these compounds on the surface of the flame, which is easily absorbed by the grilled meat. A study that investigated the concentration of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds in the air after cooking barbecue, showed that the amount of these compounds during cooking barbecue with charcoal (23.1 µg/m3) is much higher than cooking barbecue with gas (µg/m3 is 0.008)82. However, while the collected evidence indicates that the concentration of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in charcoal-grilled meats is significantly higher than that in gas-grilled meats, contrasting findings were reported by Masuda89. Their study revealed that the levels of chlorine heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, a particularly toxic class of PAHs, are markedly higher in meats grilled using gas flames compared to those grilled over charcoal. This finding underscores the importance of not only the type of fuel used in grilling but also its quality, as different fuel sources and their characteristics can significantly influence the formation and concentration of hazardous compounds in cooked meats.

Health implications and risk assessment

To determine the health risk caused by the barbecues consumed in the study area, the non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risk was calculated according to the formulas presented in the materials and methods section for the studied PAHs.

Given the elevated PAH concentrations in some of the kebabs, especially those cooked over charcoal, the potential health risks associated with regular consumption of such foods must be considered. Studies have shown that long-term exposure to PAHs, particularly benzo[a]pyrene, is linked to an increased risk of cancer90. While the non-carcinogenic risks were low, the carcinogenic risk associated with frequent consumption of kebabs grilled over charcoal was found to be higher than the acceptable limits.

Health risk assessment

Comparison with recent literature

This study’s findings were compared with those from recent literature to assess the broader implications of PAH contamination in grilled meats. Several studies have reported similar findings, with higher concentrations of PAHs in grilled foods, especially when cooked using charcoal grilling methods or at high temperatures56,65. Furthermore, studies have highlighted the importance of controlling grilling conditions, such as cooking time, temperature, and fat content, to reduce the formation of PAHs51,66.

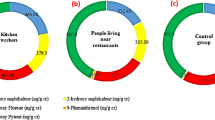

Determining non-carcinogenic risk

The HQ calculations, using formulas 1 and 2, demonstrated that oral exposure to PAHs in Zahedan’s kebab samples for both adults and children was below one, indicating a low health risk from PAH exposure in these groups. The results of non-cancer risk index (HI) using formula 3 indicated that the highest amount of HI for the samples collected in Zahedan, based on the type of meat belonging to the kebab (children: 0.0022 and adults: 0.00074) and the lowest amount of HI is in grilled chicken (children: 0.0016 and adults: 0.00052).

The value of the risk index in the three types of kebabs is less than one. Results further show that, the HQ/HI < 1, thus, there is no concern for potential human health risks caused by exposure to non-carcinogenic PAHs in kebab samples of Zahedan.

Determining the risk of carcinogenesis

The risk of carcinogenicity in the samples studied in this study was calculated orally using Formula 4. In the study of carcinogenic risk of PAH compounds based on the type of meat, the risk in red meat was higher than white meat in children and adults (kebab barg > kebab Kobideh > chicken kebab). According to calculations, the risk of white meat (kebab chicken) in children 93 × 10-9was estimated in 31 × 10–9 in adults, which was lower than the allowable limit (1 × 10–4–1 × 10–6), respectively. Also, the total risk of red meat (grilled and shredded) in children 34 × 10–8 and was estimated to be 13 × 10–8 in adults, which was less than the allowable limit (1 × 10–4-1 × 10–6), respectively. More charcoal ovens were observed than gas ovens (charcoal > gas). The result of carcinogenic risk assessment based on the type of meat in adults and children is listed in Tables 7 and 8.

According to Table 9 and 10, the risk of carcinogenicity of the gas oven was estimated to be 19 × 10–8 in children and 64 × 10–9 in adults, which is lower than the allowable limit (1 × 10–4–1 × 10–6). Also, the risk of carcinogenicity of the oven Charcoal was estimated at 24 × 10–8 in children and 80 × 10–9 in adults, which is lower than the allowable limit (1 × 10–4–1 × 10–6). Dafeng Jiang et al. reported that the carcinogenic risk of PAHs in grilled meat in Shandong, China, was less than 10–4, indicating a potentially mild carcinogenic risk to consumer health. This study was the first attempt to provide basic information on the potential health risk of dietary exposure to grilled and fried meats containing PAHs that could be useful for local consumer health management6. Yu Bon Man et al. Reported that the risk of carcinogenicity due to PAHs in freshwater fish cultured using diets based on food waste, in children and adults, was lower than allowed (1 × 10–4-1 × 10–6). They also reported a non-carcinogenic risk of less than 1 in children and adults. Based on the concentration of PAHs, freshwater fish cultured using diet-based diets are unlikely to have adverse health effects. There is great potential for the use of diet-based diets as an alternative to commercial feed for freshwater fish farming91. Aliakbar Roudbari et al., also reported that the non-carcinogenic risk of PAHs in tea and coffee samples offered in the Iranian market is negligible. And the risk of carcinogenesis was lower than the safe risk (1 × 10–4), which indicates a significant lack of risk of cancer due to digestion of tea and coffee for children and adults92. Nabi Shariatifar et al., in a study evaluating the risk of PAHs in milk powder and pasteurized milk in Iran, reported that THQ was less than 1. While the risk of carcinogenesis was higher than the allowable limit (1 × 10–4–1 × 10–6). Thus, consumers are at significant risk of carcinogenesis93. Hasan Badibostan et al. Also reported that the assessment of carcinogenic risk of PAHs in formula and infant formula was lower than the allowable limit (1 × 10–4–1 × 10–6)94. Mojtaba Yousefi et al. In a study on the compounds of PAHs in edible vegetable oils, assessed the health risk and showed that adults and children were not at significant risk for health (ILCR < 1 × 10–4)95.

This study highlights the important role of cooking methods, especially grilling, in the formation of PAHs in meat products. Given the carcinogenic and mutagenic properties of PAHs, it is important that our findings contribute to the development of dietary guidelines and food safety regulations aimed at minimizing consumer exposure to these harmful compounds."

Regulation of grilling methods

One of the most notable findings of our study is that grilling with charcoal results in higher PAH concentrations compared to gas grilling. This suggests that food safety regulations could encourage the use of gas grilling methods over charcoal grilling, particularly for meat products known to generate significant PAH levels. Public health authorities could consider recommending lower-frequency consumption of grilled meats cooked with charcoal and raising awareness of safer cooking methods, such as gas grilling or using alternative cooking technologies that reduce PAH formation.

Dietary guidelines for meat consumption

The study also highlights a higher carcinogenic risk associated with the consumption of red meat, particularly beef and lamb, compared to white meat (e.g., chicken). This finding could inform dietary guidelines that suggest a reduction in the intake of red meats, particularly grilled varieties, as a preventive measure against long-term health risks. It would be prudent for health organizations to incorporate such findings into dietary recommendations, emphasizing a more balanced diet that reduces the intake of red meat and encourages leaner proteins, such as poultry or fish.

3. Potential for reducing PAH exposure from grilled meats

Our study also points to practical strategies that could be adopted to reduce PAH exposure from grilled meats:

1. Grilling techniques and equipment modifications:

Using alternative grilling techniques or improving the design of grilling equipment could significantly lower PAH formation. For example, increasing the distance between the food and the heat source or using less fat in the preparation of meats may reduce the likelihood of PAH production. Additionally, encouraging the use of gas or electric grills, which produce fewer PAHs than charcoal, could be promoted through public health campaigns.

Reducing meat fat content

Another approach to reducing PAH exposure could involve encouraging consumers to select leaner cuts of meat. The fat in meat is a major contributor to PAH formation during grilling because it drips onto the heat source, leading to the production of smoke that contains PAHs. By promoting leaner meat options and reducing the fat content in grilled products, PAH exposure could be minimized.

3. Marinating and cooking time adjustments:

Research has shown that marinating meat before grilling can reduce PAH formation. By incorporating this strategy into dietary guidelines or food safety protocols, consumers can be educated on the benefits of marinating meats for a certain duration to reduce PAH production. Additionally, recommendations on optimal cooking times and temperatures could further minimize PAH formation, helping to reduce the health risks associated with grilled meats.

Below are the proposed solutions to mitigate PAH formation and its associated risks:

Modification of grilling techniques

Use of gas grills instead of charcoal:

Our study found that grilling with charcoal results in higher PAH concentrations than gas grilling. One of the most effective ways to reduce PAH exposure is to shift from charcoal-based grilling methods to gas or electric grills. These grilling methods generate lower levels of PAHs because they typically produce less smoke, which is a primary source of PAH contamination in food.

Solution: Encourage consumers to opt for gas or electric grills, especially in restaurants or home grilling situations. Public awareness campaigns could highlight the health risks associated with charcoal grilling and promote safer alternatives.

Increasing distance between meat and heat source:

A key factor influencing PAH formation is the proximity of meat to the heat source. When meat is placed too close to the heat, fats and juices drip onto the coals or heat source, producing smoke that carries PAHs.

Solution: Increasing the distance between the meat and the heat source can reduce PAH exposure. Grills that allow for better control of this distance could be promoted, or people could be instructed to adjust their cooking setups for safer grilling.

Indirect grilling and cooking at lower temperatures:

Direct exposure to high heat is another contributor to PAH formation. Indirect grilling, where food is cooked with heat from the sides or above, rather than directly over the flame, can significantly lower PAH levels. Additionally, cooking at lower temperatures for a longer duration can reduce the formation of these compounds.

Solution: Educating consumers and food industry professionals on the benefits of indirect grilling and the importance of cooking meats at moderate temperatures (avoiding charring or overcooking) will help reduce PAH exposure.

Modification of meat preparation

Reducing fat content in meat:

Fat in meat is a major contributor to PAH formation during grilling because it drips onto the heat source, creating smoke that contains PAHs. The higher the fat content in the meat, the more PAHs are likely to be formed.

Solution: Encouraging the consumption of leaner cuts of meat (e.g., skinless chicken, lean cuts of beef or pork) can reduce PAH exposure. Additionally, removing visible fat before grilling can minimize PAH formation.

Marinating meat to reduce PAH formation:

Research suggests that marinating meat before grilling can reduce PAH formation. Certain ingredients in marinades, such as vinegar, olive oil, or herbs, have been shown to act as protective barriers, reducing the amount of fat that drips onto the heat source and decreasing PAH levels.

Solution: Encourage consumers to marinate their meats before grilling, particularly with marinades that have been shown to reduce PAH formation. This can be included as part of dietary guidelines or consumer education campaigns.

Public health and regulatory measures

Regulation of PAH levels in grilled foods

Similar to other food contaminants (e.g., pesticide residues), the regulation of permissible PAH levels in grilled meat products could be an effective measure to protect public health. Regulatory agencies could set maximum allowable PAH concentrations in foods sold at restaurants, street vendors, or supermarkets.

Solution: Implement food safety regulations that set limits for PAH levels in grilled meats, and ensure regular monitoring to enforce compliance with these standards.

Public awareness campaigns and guidelines

Public health organizations can play a crucial role in educating the public about the risks of PAH exposure from grilled meats and the steps that can be taken to reduce these risks. This could include recommendations for safer grilling techniques, the importance of selecting leaner meats, and the benefits of marinating.

Solution: Launch public health campaigns and include information in dietary guidelines that provide consumers with knowledge about safer grilling practices and the potential health risks of PAH exposure.

Development of safer grilling technologies

Another long-term solution could involve the development and promotion of new grilling technologies that minimize PAH formation. Innovations in grilling equipment, such as advanced grills with smoke reduction systems or heat management features, could be encouraged.

Solution: Promote research and development into safer grilling technologies that minimize PAH exposure. Encourage manufacturers to create and market these technologies to both professional food services and home users.

Reducing red meat consumption

Our study found that red meat (especially beef) was associated with higher PAH concentrations compared to white meat (such as chicken). Reducing red meat consumption can, therefore, help lower PAH exposure and improve overall health outcomes.

Solution: Encouraging a shift towards consuming more white meat (e.g., poultry, fish) and plant-based alternatives could contribute to a reduction in PAH exposure, as well as other health benefits.

While charcoal grilling is still popular due to its flavor profile, the results of this study suggest that gas grilling may offer a cleaner and safer alternative in terms of PAH contamination. However, the health risks associated with both methods must be taken seriously, and future efforts should focus on improving grilling practices and reducing harmful emissions. By addressing these concerns, we can ensure that consumers continue to enjoy grilled foods while minimizing the associated health risks.

Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate the concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in kebabs grilled using different methods, specifically comparing charcoal and gas grilling. The results demonstrate that charcoal grilling leads to significantly higher levels of PAH contamination in kebabs, especially in chicken kebabs, which are typically higher in fat content. This finding is consistent with the well-established notion that fatty foods tend to absorb more PAHs due to the lipophilic properties of these compounds. Furthermore, charcoal grilling produced higher levels of carcinogenic PAHs, particularly benzo[a]pyrene, which is a well-known human carcinogen.

Conversely, gas grilling, which involves more controlled combustion, generally resulted in lower PAH concentrations, suggesting that it may be a safer alternative from a health perspective. However, while gas grilling reduces PAH formation, it is not entirely free from producing harmful emissions, and further efforts are needed to minimize these risks in grilling practices.

The risk assessment conducted as part of this study revealed that the consumption of grilled meats, particularly those cooked over charcoal, poses an elevated health risk, primarily due to the carcinogenic PAH compounds detected. This study highlights the importance of reducing PAH exposure, especially for individuals who frequently consume grilled meats, and suggests that health risk mitigation measures, such as optimizing grilling conditions and exploring alternative fuels, should be prioritized. The findings of this study have important implications for dietary guidelines and food safety regulations. We hope that these insights contribute to future policymaking aimed at reducing PAH exposure from grilled foods, thereby promoting public health.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Huang H-f, Xing X-l, Zhang Z-z, Qi S-h, Yang D, Yuen DA, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in multimedia environment of Heshan coal district, Guangxi: distribution, source diagnosis and health risk assessment. Environmental geochemistry and health 381169-1181 (2016).

Al-Rashdan, A., Helaleh, M. I., Nisar, A., Ibtisam, A. & Al-Ballam, Z. Determination of the levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in toasted bread using gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2010(1), 821216 (2010).

Onwukeme V, Obijiofor O, Asomugha R, Okafor F. Impact of cooking methods on the levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in chicken meat. IOSR Journal of Environmental Science Ver I. 9:2319–2399.

Abou-Arab, A., Abou-Donia, M., El-Dars, F., Ali, O. & Hossam, A. Detection of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons levels in Egyptian meat and milk after heat treatment by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 3(7), 294–305 (2014).

Farhadian, A., Jinap, S., Abas, F. & Sakar, Z. I. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in grilled meat. Food Control 21(5), 606–610 (2010).

Jiang, D. et al. Occurrence, dietary exposure, and health risk estimation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in grilled and fried meats in Shandong of China. Food Sci. Nutr. 6(8), 2431–2439 (2018).

Kim Y-Y, Patra J-K, Shin H-S. Evaluation of analytical method and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons for fishery products in Korea. Food control 131:108421 (2022).

Luper Tsenum J, Yarkwan B. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Food Contamination: A contributing Factor to Rising Carcinogenicity. ScienceOpen Preprints. 2020.

Nsonwu-Anyanwu AC, Helal M, Khaked A, Eworo R, Usoro CAO, El-Sikaily A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons content of food, water and vegetables and associated cancer risk assessment in Southern Nigeria. Plos one. 2024;19(7):e0306418

Demirok E, Kolsarıcı N. Effect of green tea extract and microwave pre-cooking on the formation of acrylamide in fried chicken drumsticks and chicken wings. Food Research International. 2014;63:290-8.

Eldaly E, Hussein M, El-Gaml A, El-hefny D, Mishref M. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in charcoal grilled meat (kebab) and Kofta and the effect of marinating on their existence. Zagazig Veterinary Journal. 2016;44(1):40-7

Janoszka B, Warzecha L, Blaszczyk U, Bodzek D. Organic compounds formed in thermally treated high-protein food. Part I: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Acta Chromatographica. 2004:115-28.

Kiani A, Ahmadloo M, Moazzen M, Shariatifar N, Shahsavari S, Arabameri M, et al. Monitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and probabilistic health risk assessment in yogurt and butter in Iran. Food Science & Nutrition. 2021;9(4):2114-28

Gorji MEh, Ahmadkhaniha R, Moazzen M, Yunesian M, Azari A, Rastkari N. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Iranian Kebabs. Food control. 60, 57–63 (2016).

Bukowska B, Mokra K, Michałowicz J. Benzo [a] pyrene—Environmental occurrence, human exposure, and mechanisms of toxicity. International journal of molecular sciences 236348 (2022).

Alomirah H, Al-Zenki S, Al-Hooti S, Zaghloul S, Sawaya W, Ahmed N, et al. Concentrations and dietary exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from grilled and smoked foods. Food control 22, 2028-2035 (2011).

Carrabs G, Marrone R, Mercogliano R, Carosielli L, Vollano L, Anastasio A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons residues in Gentile di maiale, a smoked meat product typical of some mountain areas in Latina province (Central Italy). Italian Journal of Food Safety 3 1681 (2014).

Sadighara P. Antioxidants as Modulators of PAH Contaminants in Food and Living Organisms: An Overview Study. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 123–135 (2025).

Pearce N, Blair A, Vineis P, Ahrens W, Andersen A, Anto JM, et al. IARC monographs: 40 years of evaluating carcinogenic hazards to humans. Environmental health perspectives 123507–14 (2015).

Diggs DL, Huderson AC, Harris KL, Myers JN, Banks LD, Rekhadevi PV, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and digestive tract cancers: a perspective. Journal of environmental science and health 29(4), 324-57 (2011).

Mallah MA, Changxing L, Mallah MA, Noreen S, Liu Y, Saeed M, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and its effects on human health: An overeview. Chemosphere. 296, 133948 (2022).

Yin S, Tang M, Chen F, Li T, Liu W. Environmental exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): The correlation with and impact on reproductive hormones in umbilical cord serum. Environmental Pollution 220 1429–1437 (2017).

Pieterse B, Felzel E, Winter R, Van Der Burg B, Brouwer A. PAH-CALUX, an optimized bioassay for AhR-mediated hazard identification of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) as individual compounds and in complex mixtures. Environmental science & technology 47(20), 11651-9 (2013).

Carrabs G, Marrone R, Mercogliano R, Carosielli L, Vollano L, Anastasio A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons residues in Gentile di maiale, a smoked meat product typical of some mountain areas in Latina province (Central Italy). Italian Journal of Food Safety 3, (2014).

Ghaderpoori, M. et al. Health risk assessment of fluoride in water distribution network of Mashhad Iran. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 25(4), 851–862 (2019).

Khoshakhlagh AH, Ghobakhloo S, Al Sulaie S, Yazdanirad S, Gruszecka-Kosowska A. A Monte Carlo simulation and meta-analysis of health risk due to formaldehyde exposure at different seasons of the year in various indoor environments. Science of The Total Environment 965, 178641. (2025).

Khoshakhlagh AH, Mohammadzadeh M, Gruszecka-Kosowska A. Dermatitis, a nightmare for those exposed to environmental pollutants. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, 100454 (2024).

Khoshakhlagh AH, Yazdanirad S, Hopke PK. Effects of seasons and weather on occupational exposure to BTEX concentrations in a changing climate. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 1-17 (2025).

Khoshakhlagh AH, Yazdanirad S, Moda HM, Gruszecka-Kosowska A. The impact of climatic conditions on the carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk of BTEX compounds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, 100470 (2023).

Ghobakhloo S, Khoshakhlagh AH, Alwan N, Carlsen L. Health Risk Assessment of Exposure to BTEX and PAH Compounds in Workers of Burnt Oil Recycling Factory: Simulation Using Monte Carlo Method. Environmental Processes 11, 37 (2024).

Huang Y, Fang M. Nutritional and environmental contaminant exposure: a tale of two co-existing factors for disease risks. Environmental science & technology 54(23), 14793-14796. (2020).

Amfo-Otu R, Agyenim JB, Adzraku S. Meat contamination through singeing with scrap tyres in Akropong-Akuapem abattoir, Ghana. Applied Research Journal 1(1) (2014).

Ebrahimi F, Aryaeian N, Pahlavani N, Abbasi D, Hosseini AF, Fallah S, et al. The effect of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) supplementation on blood pressure, and renal and liver function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A double-blinded, randomized clinical trial. Avicenna journal of phytomedicine 9(4), 322 (2023).

Sahin S, Ulusoy HI, Alemdar S, Erdogan S, Agaoglu S. The presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in grilled beef, chicken and fish by considering dietary exposure and risk assessment. Food Science of Animal Resources 40(5) 675 (2020).

Ghaderpoori M, Paydar M, Zarei A, Alidadi H, Najafpoor AA, Gohary AH, et al. Health risk assessment of fluoride in water distribution network of Mashhad, Iran. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal. 25(4), 851-62 (2019).

Dehghani M, Shahsavani S, Mohammadpour A, Jafarian A, Arjmand S, Rasekhi MA, et al. Determination of chloroform concentration and human exposure assessment in the swimming pool. Environmental Research 203, 111883 (2022).

Mohammadpour A, Emadi Z, Keshtkar M, Mohammadi L, Motamed-Jahromi M, Samaei MR, et al. Assessment of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in fruits from Iranian market (Shiraz): A health risk assessment study. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 114, 104826 (2022).

Mohammadpour A, Hosseini MR, Dehbandi R, Khodadadi N, Keshtkar M, Shahsavani E, et al. Probabilistic human health risk assessment and Sobol sensitivity reveal the major health risk parameters of aluminum in drinking water in Shiraz, Iran. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 45, 7665–77 (2023).

Abou-Arab A, Abou-Donia M, El-Dars F, Ali O, Hossam A. Detection of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons levels in Egyptian meat and milk after heat treatment by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 3(7), 294–305 (2014).

Akpambang V, Purcaro G, Lajide L, Amoo I, Conte L, Moret S. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in commonly consumed Nigerian smoked/grilled fish and meat. Food additives and contaminants 26(7), 1096-103 (2009).

Mohammadpour A, Zarei AA, Dehbandi R, Khaksefidi R, Shahsavani E, Rahimi S, et al. Comprehensive assessment of water quality and associated health risks in an arid region in south Iran. Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology 135 105264 (2022).

Mohammadpour A, Rajabi S, Bell M, Baghapour MA, Aliyeva A, Mousavi Khaneghah A. Seasonal variations of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in drinking water and health risk assessment via Monte Carlo simulation and Sobol sensitivity analysis in southern Iran's largest city. Applied Water Science 13, 237 (2023).

Mohammadpour A, Samaei MR, Baghapour MA, Sartaj M, Isazadeh S, Azhdarpoor A, et al. Modeling, quality assessment, and Sobol sensitivity of water resources and distribution system in Shiraz: A probabilistic human health risk assessment. Chemosphere 341, 139987 (2023).

Chung S, Yettella RR, Kim J, Kwon K, Kim M, Min DB. Effects of grilling and roasting on the levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in beef and pork. Food Chemistry 129(4),1420–1426 (2011).

Mohammadpour A, Emadi Z, Samaei MR, Ravindra K, Hosseini SM, Amin M, et al. The concentration of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in drinking water from Shiraz, Iran: a health risk assessment of samples. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30(9), 23295-23311 (2023).

Amarh FA, Agorku ES, Voegborlo RB, Ashong GW, Atongo GA. Health risk assessment of some selected heavy metals in infant food sold in Wa, Ghana. Heliyon. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 9(5) (2023).

Amerley Amarh F, Selorm Agorku E, Bright Voegborlo R, Winfred Ashong G, Nii Klu Nortey E, Jackson Mensah N. Heavy Metal Content and Health Risk Assessment of Some Selected Medicinal Plants from Obuasi, a Mining Town in Ghana. Journal of Chemistry 2023(1), 9928577 (2023).

Singh, L., Varshney, J. G. & Agarwal, T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons’ formation and occurrence in processed food. Food Chem. 199, 768–781 (2016).

Hosseini NS, Sobhanardakani S. Concentration, sources, potential ecological and human health risks assessment of trace elements in roadside soil in Hamedan metropolitan, west of Iran. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry 104(17), 5962-85 (2024).

Zhang Y, Liu P, Wang C, Wu Y. Human health risk assessment of cadmium via dietary intake by children in Jiangsu Province, China. Environmental geochemistry and health 39, 29-41 (2017).

Liu R, Liu H-C, Shi H, Gu X. Occupational health and safety risk assessment: A systematic literature review of models, methods, and applications. Safety science 160, 106050 (2023).

Wang J, Yan Z, Zheng X, Wang S, Fan J, Sun Q, et al. Health risk assessment and development of human health ambient water quality criteria for PBDEs in China. Science of the Total Environment 799, 149353 (2021).

Hosseini K, Taghavi L, Ghasemi S, Dehghani Ghanatghestani M. Health risk assessment of total petroleum hydrocarbons and heavy metals in groundwater and soils in petrochemical pipelines. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 20(2), 1411–1420 (2023).

Mohammadpour A, Abbasi F, Gili MR, Kazemi A, Bell ML. Evaluation of concentration and characterization of potential toxic elements and fluorine in ambient air dust from Iran’s industrial capital: a health risk assessment using Monte Carlo simulation. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 132, 103998 (2024).

Shaterian M, Mirzaei A. Evaluation of Youth Empowerment in Informal Settlements (Case Study: Ali Ibn Abitaleb Neighbourhood, Arak City). Spatial Planning 12, 23–42 (2022).

Zhao, L. et al. Potential toxicity risk assessment and priority control strategy for PAHs metabolism and transformation behaviors in the environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(17), 10972 (2022).

Jiang G, Song X, Xie J, Shi T, Yang Q. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in ambient air of Guangzhou city: Exposure levels, health effects and cytotoxicity. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 262, 115308 (2023).

Wang Y-S, Wu F-X, Gu Y-G, Huang H-H, Gong X-Y, Liao X-L. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the intertidal sediments of Pearl River Estuary: Characterization, source diagnostics, and ecological risk assessment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 173, 113140 (2021).