Abstract

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) resulting from neurodegeneration due to chemotherapy is a challenging complication of widely administered anticancer drugs including paclitaxel. Although CIPN is common and limits the use of chemotherapies, no curative treatment for CIPN has been developed. Recently, stimulation of mitophagy has emerged as a promising strategy for treating neurodegenerative diseases, but studies on its therapeutic effects on CIPN are limited. In this study, we examined the therapeutic effect of the recently developed mitophagy inducer ALT001 on paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy model in Drosophila and mice. Importantly, ALT001 administration in a paclitaxel-induced Drosophila model of peripheral neuropathy significantly ameliorated paclitaxel-induced alterations in sensory neurons and the thermal hyperalgesia phenotype in a mitophagy-dependent manner. Moreover, we demonstrated that ALT001 administration significantly ameliorated paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia and the reduction in intraepidermal nerve fiber density in a mouse model. Interestingly, ALT001 did not interfere with the cytotoxic effect of paclitaxel on lung cancer or breast cancer cells. Our results suggest that ALT001 is a potential candidate for the treatment of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy and that stimulation of mitophagy is a promising strategy for CIPN treatment that does not affect the cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a common complication associated with various widely used anticancer drugs, such as paclitaxel, vincristine, and bortezomib1. Patients with CIPN experience a range of painful sensory and motor symptoms, including burning pain, muscle cramps, allodynia, and hyperalgesia2,3. Over 60% of patients are estimated to develop neuropathy within a month of starting chemotherapy, with a substantial portion continuing to experience chronic or irreversible symptoms even after treatment ends4,5. These persistent effects frequently lead to dose reduction or early termination of chemotherapy, thereby compromising cancer treatment outcomes6,7. Despite the high prevalence of this condition, no effective therapies currently exist to prevent or reverse CIPN. The underlying mechanisms of CIPN are not fully understood, but accumulating evidence highlights the central role of sensory neuron degeneration in the pathogenesis of CIPN8. A growing number of studies have shown that sensory neuron loss or degeneration closely correlates with the onset and severity of CIPN symptoms, underscoring its central role in this condition8,9. For example, numerous studies have provided evidence of axonal degeneration from nerve biopsies in patients with CIPN that correlates with the severity of CIPN (reviewed previously10. Additionally, intraepidermal nerve fiber (IENF) density has been shown to be closely correlated with the severity of sensory peripheral neuropathy in patients11. These studies underscore the need for novel interventions that can halt or reverse neuronal degeneration to effectively treat CIPN. In addition, extensive research has revealed that various factors, such as mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired axonal transport, abnormal calcium signaling, and neuroinflammation, contribute to sensory neuron loss and degeneration in CIPN patients8,9,10,12.

Mitophagy, the selective clearance of damaged mitochondria, has recently emerged as a promising strategy for mitigating sensory neuron degeneration and maintaining neuronal health in various neuropathic and neurodegenerative conditions. Promotion of the PINK1-Parkin pathway, for example, has been shown to prevent neuronal loss and degeneration in several CIPN and diabetic neuropathy models13,14,15. Yang et al. also recently showed that the overexpression of SIRT3 restored mitophagy and prevented axonal loss in a mouse model of diabetic neuropathy16. These findings suggest that increasing mitophagy may be a novel strategy for attenuating sensory neuron degeneration in CIPN. For mitophagy-based CIPN therapies to advance, identifying compounds that are both clinically applicable and validated for their therapeutic efficacy in CIPN models is essential.

In this study, we investigated the therapeutic effects of ALT001, a recently validated mitophagy-inducing compound that promotes ULK1-Rab9-mediated alternative mitophagy without causing mitochondrial dysfunction or cellular toxicity17, making it a promising candidate for clinical application, in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy models. ALT001 alleviated the degeneration of sensory neurons and sensory abnormalities in both Drosophila and mouse models of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. These findings confirm that induction of mitophagy is an effective therapeutic strategy for CIPN and suggest that ALT001 is a novel therapeutic candidate.

Results

The novel isoquinoline derivative mitophagy inducer ALT001 alleviates paclitaxel-induced alterations in sensory neurons in a Drosophila model

The isoquinoline derivative ALT001 has been identified as a novel mitophagy inducer that efficiently stimulates mitophagy while exhibiting low toxicity17. To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of ALT001 in CIPN, we employed a previously established Drosophila model of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy, which enables quantitative assessment of heat hyperalgesia and morphological alterations in sensory neurons18,19. To confirm the mitophagy-inducing effect of ALT001 in sensory neurons, we utilized Drosophila larvae expressing the pH-sensitive mitophagy probe mt-Keima, specifically expressed in C4da sensory neurons (ppk1a > mt-Keima). The increase in red puncta, a characteristic indicator of mitophagy, was confirmed through confocal microscopy analysis and was found to correlate with increasing concentrations of ALT001 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Mitophagy quantification using a previously established method20,21 revealed that ALT001 treatment at 750 µM led to an approximately 59% increase in mitophagy levels in C4da neurons (Fig. 1A). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis further demonstrated that ALT001 treatment reduced the mRNA levels of mitochondrial DNA-encoded genes, such as ND5, Cyt-b, and Cox2, while increasing the expression of key mitochondrial biogenesis regulators, including PGC-1α, TFAM, and EWG (a homologue of human NRF-1)22 (Supplementary Fig. S2). These results are consistent with our previous findings17 and suggest that ALT001 promotes mitophagy followed by mitochondrial biogenesis not only in mammalian cells but also in Drosophila.

Next, we investigated how ALT001 influences paclitaxel-induced changes in the dendritic architecture of C4da neurons. Alterations in dendrite structure of C4da neurons are closely associated with the development of peripheral neuropathy phenotypes upon paclitaxel treatment19,23. Visualization of C4da neuron dendrites using the plasma membrane marker CD4-tdTomato allowed for dendritic arborization analysis, revealing that paclitaxel treatment significantly enhanced dendrite length and increased the number of branch points in C4da neurons (Fig. 1B-D), which is consistent with previous reports19,23. Paclitaxel treatment led to a 23.6% increase in dendrite length and a 35.7% rise in the number of branch points in C4da neurons (Fig. 1B-D). Notably, cotreatment with ALT001 fully prevented paclitaxel-induced increases in dendrite length and branch point numbers in C4da neurons (Fig. 1B-D). Quantitative analysis of multiple C4da neurons (n ≧ 13) showed that, in the presence of ALT001, paclitaxel did not induce significant changes in dendrite length or branch point number (Fig. 1B-D). These results suggest that ALT001 may alleviate the paclitaxel-induced thermal hypersensitivity through the suppression of altered dendrite arborization.

ALT001 alleviates paclitaxel-induced alterations in C4da neurons in Drosophila larvae. (A) Fluorescence images representing mt-Keima-labeled mitochondria in C4da sensory neurons of L3 control larvae (ppk1a > mt-Keima) at abdominal segment A4 following 48 h treatment with DMSO (Veh) or ALT001 (750 µM) (left). Scale bars, 10 μm. Mitophagy levels in C4da sensory neurons were quantified across experimental groups (n = 12 per group) (right). (B) Representative images illustrating C4da neurons of L3 control larvae (ppk1a > CD4-tdTom) at abdominal segment A4 following 48 h treatment with DMSO (Veh) or ALT001 (750 µM) (left). Enlarged views of the boxed regions are displayed in the lower panel. Scale bars, 50 μm. (C–D) Quantification of dendritic morphology, including dendrite length (C) and the number of dendritic branch points (D) in C4da neurons (n = 13–14 per sample). A single C4da neuron per larva was analyzed. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test (A) or one-way ANOVA followed by Sidák’s correction (C, D). Unless otherwise noted, differences are not statistically significant. ** p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant.

ALT001 alleviates paclitaxel-induced heat hyperalgesia

Next, we investigated how ALT001 affects paclitaxel-induced hyperalgesia, a key characteristic of CIPN2,3. The results from the thermal nociception assay indicated that paclitaxel treatment (20 µM) significantly reduced the mean withdrawal latency (MWL), the time required to trigger the aversive corkscrew-like rolling response (Fig. 2A). Paclitaxel treatment led to a reduction in MWL from 7.2 s to 4.5 s, representing an approximate 56% decrease. This reduction indicates the development of a hyperalgesic phenotype, consistent with previous reports19,23. Importantly, ALT001 cotreatment completely prevented the paclitaxel-induced decrease in the MWL (Fig. 2A), suggesting that ALT001 mitigated the heat hypersensitivity phenotype resulting from paclitaxel treatment.

ALT001 mitigates heat hyperalgesia caused by paclitaxel treatment in Drosophila larvae. (A) Drosophila L3 larvae (ppk > w1118) were exposed to paclitaxel (20 µM) either alone or in combination with ALT001 (750 µM) for 48 h, and a thermal nociception assay was performed with a 40 °C heat probe (n ≧ 90 per sample). (B) Representative images showing larvae from each experimental group in (A). The larval area, calculated as the product of length and width, was measured and plotted (n ≧ 90 per sample) (right). Scale bars, 1 mm. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple-comparison test. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant.

Interestingly, the MWL did not significantly change upon ALT001 treatment (Fig. 2A), suggesting that ALT001 had no impact on the thermal nociceptive response in Drosophila larvae. Furthermore, larvae treated with ALT001 exhibited no significant size difference compared to control larvae (Fig. 2B), suggesting that ALT001 did not affect larval growth. As reported in previous studies19,23, paclitaxel significantly suppresses larval growth, and this effect persisted even when larvae were cotreated with ALT001 (Fig. 2B), suggesting that ALT001 does not reduce the impact of paclitaxel on larval growth.

ALT001 mitigates heat hypersensitivity caused by paclitaxel through the alternative mitophagy pathway

We then examined whether mitophagy is essential for the therapeutic effects of ALT001 on hyperalgesia resulting from paclitaxel treatment. We previously demonstrated that ALT001 induces mitophagy in a ULK1-Rab9 alternative pathway dependent manner, while being independent of ATG7 or PINK1 17. Consistent with this observation, C4da neuron-specific knockdown of the ATG5 or ATG7 genes, which are essential genes in the canonical mitophagy pathway24, did not interfere with the ALT001-mediated therapeutic effect on paclitaxel-induced hyperalgesia (Fig. 3A, B).

Therapeutic effects of ALT001 on paclitaxel-induced heat hyperalgesia in a Drosophila larval model are independent of ATG5 and ATG7. (A–B) Drosophila L3 larvae expressing control RNAi (CON RNAi), and ATG5 RNAi (A), or ATG7 RNAi (B) were expose to paclitaxel (20 µM) either alone or in combination with ALT001 (750 µM) for 48 h, and a thermal nociception assay was performed with a 40 °C heat probe (n ≧ 40 per sample). Significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple-comparison test. ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant.

However, C4da neuron-specific knockdown of ATG6 (Beclin1), ULK1 or Rab9 gene, which is essential gene in the alternative mitophagy pathway25, completely eliminated the therapeutic effect of ALT001 on paclitaxel-induced hyperalgesia (Fig. 4A-C). These results indicated that ALT001 ameliorated the paclitaxel-induced nociceptive sensitization through the induction of mitophagy via alternative pathway.

Blocking the alternative mitophagy pathway eliminates the therapeutic effect of ALT001 on the paclitaxel-induced heat hyperalgesia phenotype in a Drosophila larval model. (A–C) Drosophila L3 larvae expressing control RNAi (CON RNAi), and ULK1 RNAi (A), Rab9 RNAi (B), or ATG6 RNAi (C) were exposed to paclitaxel (20 µM) either alone or in combination with ALT001 (750 µM) for 48 h, and a thermal nociception assay was performed with a 40 °C heat probe (n ≧ 50 per sample). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple-comparison test. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant.

ALT001 ameliorates mechanical allodynia and prevents loss of IENF density associated with paclitaxel treatment in a mouse model

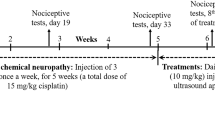

To further verify the therapeutic efficacy of ALT001, we tested its effect in a mouse model of peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel treatment. Paclitaxel administration results in peripheral neuropathy phenotypes, including mechanical allodynia and a decrease in IENFs26,27. Indeed, mice receiving repeated paclitaxel injections (16 mg/kg, i.p.) exhibited a significantly lower paw withdrawal threshold in the von Frey test than the vehicle-treated controls on day 15 (p < 0.01; Fig. 5A). Importantly, cotreatment with ALT001 (10 mg/kg i.p.) significantly alleviated the reduction in the thresholds caused by paclitaxel (p < 0.05; Fig. 1A).

Loss of IENFs is a representative characteristic of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, and paclitaxel administration is known to induce a decrease in IENFs in both animals and patients28,29. The assessment of IENFs consistently revealed an approximately 25% decrease in the number of IENFs in the hind paw skin relative to that in the control group (Fig. 5B). ALT001 cotreatment also significantly inhibited the loss of IENFs (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that ALT001 mitigates sensory dysfunction and neuronal degeneration in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy, not only in a Drosophila model but also in a mouse model.

ALT001 mitigates mechanical allodynia and the loss of IENFs caused by paclitaxel treatment in a mouse model. (A) C57BJ mice were injected intraperitoneally with paclitaxel (16 mg/kg) either alone or in combination with ALT001 (10 mg/kg), four times every four days. Mechanical allodynia was assessed on day 16 using the von Frey test (n = 6 per group). (B) Representative fluorescence images of IENFs in the plantar surface of hind paws from mice in (A), stained with PGP 9.5. Scale bars, 25 μm. The number of fibers crossing from the dermis to the epidermis was quantified relative to skin length (n = 6 per group) (right). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple-comparison test. *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant.

ALT001 does not compromise the cytotoxic effect of Paclitaxel in lung and breast cancer cells

To assess the potential impact of ALT001 on the cytotoxicity of paclitaxel, we conducted a clonogenic survival assay in A549 lung cancer and MCF7 breast cancer cells treated with paclitaxel in the presence or absence of ALT001. The analysis of clonogenic survival revealed that ALT001 cotreatment did not lead to a significant change in the viability of A549 and MCF7 cells treated with paclitaxel (Fig. 6A, B). These results suggest that ALT001 does not compromise the cytotoxic potential of paclitaxel at least in lung and breast cancer cells.

Impact of ALT001 on the cytotoxic effects of paclitaxel in lung and breast cancer cells. (A–B) Clonogenic survival of A549 lung cancer cells (A) and MCF7 breast cancer cells (B) was assessed following treatment with paclitaxel (20 µM) alone or in combination with ALT001 (15 µM). Colonies were stained with methylene blue after 10–12 days and counted. Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple-comparison test. NS, not significant.

Discussion

The development of drugs that prevent chemotherapy-induced neuronal degeneration while preserving its anticancer efficacy is critical for treating CIPN. In this study, we demonstrated that the recently developed mitophagy inducer ALT001 has therapeutic effects on paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in Drosophila and mouse models. ALT001 treatment alleviated sensory neuronal alterations and heat hyperalgesia phenotypes in a Drosophila model of paclitaxel-induced neuropathy. Furthermore, ALT001 effectively lessened mechanical allodynia and protected against IENF loss in a paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy mouse model. Importantly, ALT001 did not compromise paclitaxel-induced cancer cell death. These results suggest that ALT001 confers neuroprotection from paclitaxel-induced toxicity while preserving the anticancer efficacy of paclitaxel.

Induction of mitophagy is increasingly recognized as an effective therapeutic strategy for addressing mitochondrial dysfunction in various neurodegenerative disease models30,31,32,33. The targeted elimination of impaired mitochondria through mitophagy is vital for sustaining mitochondrial function and avoiding the accumulation of damaged mitochondria34. Defects in mitochondrial function can impair neuronal function and survival35,36. Previous studies in various cellular and animal models have indicated that anticancer drugs impair mitochondrial function in peripheral neurons, significantly contributing to CIPN onset37,38.

Recent studies revealed that anticancer drugs, including paclitaxel, induces various mitochondrial defects, such as swelling, decreased oxygen utilization, and impaired ATP generation39,40,41,42. Moreover, while mitochondrial toxins such as rotenone and oligomycin worsen paclitaxel-induced sensory phenotypes43, interventions designed to promote mitochondrial function have ameliorated CIPN symptoms42,44,45,46.

We also previously reported that the expression of PINK1 or treatment with the PINK1 activator niclosamide alleviates thermal hyperalgesia caused by paclitaxel18,19. According to these studies, stimulating mitophagy, which plays a vital role in mitochondrial function, may offer a viable therapeutic option for CIPN. Consistent with this notion, in the present study, ALT001, an alternative mitophagy pathway-specific inducer, successfully ameliorated paclitaxel-induced neuronal degeneration and sensory symptoms in both Drosophila and mouse models. Our results further support the notion that stimulation of mitophagy is a promising therapeutic strategy for CIPN. Given the central role of chemotherapy-induced neurodegeneration in CIPN, promotion of mitophagy could alleviate peripheral neuropathy associated with other chemotherapeutic drugs.

Our study also highlights that targeting the alternative mitophagy pathway could be beneficial for CIPN treatment. Previous intense studies have established the critical role of the PINK1-Parkin-dependent canonical pathway in the removal of damaged mitochondria24,47. However, recent studies have revealed the important role of the alternative mitophagy pathway in maintaining mitochondrial function25,48. We recently showed that ALT001 alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction in the hippocampal region and cognitive defects in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models17. ATG5 and ATG7 are not required for the alternative mitophagy pathway17,49. Instead, ULK1, Rab9, and ATG6 (Beclin1) are essential for proper induction17,25. Consistently, we found that ALT001 alleviated paclitaxel-induced thermal hyperalgesia in ATG5 and ATG7 Drosophila larvae, but knocking down of ULK1, Rab9, or ATG6 abolished the ALT001-mediated therapeutic effect. Our results suggest that stimulating the ULK1-Rab9 alternative mitophagy pathway is beneficial for ameliorating neuronal degeneration upon paclitaxel treatment. While our study revealed that ALT001 ameliorates paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy, the underlying molecular mechanisms by which induction of mitophagy prevents paclitaxel-induced neuronal degeneration remain unclear. A recent study showed that stimulation of mitophagy alleviates neuropathic pain by inhibiting inflammasome activation in a chronic constrictive injury mouse model50. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether ALT001 exerts neuroprotective effects through a similar mechanism. Although our Drosophila and mouse models provide important in vivo evidence, further studies utilizing human neuronal cell lines will be critical to dissect the cellular mechanisms and validate the translational potential of ALT001. In addition, although no adverse effects were detected in the vehicle control group administered with 5% DMSO and 10% Tween 80, the pharmacological effects of ALT001 should be validated using DMSO-free formulations to conclusively attribute the observed biological effects to the compound itself. Similarly, given the potential differences between experimental and clinical formulations, it may be important to consider evaluating paclitaxel using clinically approved formulations in future research to improve translational applicability.

In conclusion, although the precise molecular mechanisms by which the alternative mitophagy pathway confers neuroprotection against paclitaxel-induced neuronal damage remain to be elucidated, our study identified ALT001 as a promising therapeutic candidate for paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. This study underscores the therapeutic potential of induction of mitophagy in mitigating the neuropathic symptoms associated with chemotherapy while preserving the anticancer efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents.

Materials and methods

Drosophila strains and treatments

The w1118, ppk-GAL4, ppk1a-GAL4, UAS-mt-Keima, UAS-CD4-tdTomato (CD4-tdTom), and UAS-mito-roGFP2-Orp1 lines were described previously18,19. UAS-ATG7 RNAi (5489R-2) and UAS-Rab9 RNAi (9994R-3) were obtained from the National Institute of Genetics (Mishima, Japan). UAS-ATG5 RNAi (BDSC 27551), UAS-ATG6 RNAi (BDSC 35741), and UAS-ULK1 RNAi (BDSC 44034) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA).

Paclitaxel (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was administered according to a previously described feeding regimen18,19. Briefly, following a 48–72 h mating period between twenty virgin females and fifty males, embryos were harvested on grape juice agar plates within 2–4 h. After incubating for 72 h, the embryos matured into L3 larvae. After being rinsed with distilled water, the larvae were relocated onto newly prepared grape juice agar plates supplemented with either 20 µM paclitaxel or 0.2% EtOH. The thermal nociception assay was performed after the larvae had been cultured for another 48 h. ALT001 was synthesized as described previously17. In a dried 250 mL round-bottom flask, palmatine (1 g, 2.92 mmol) was dissolved in 40 mL of anhydrous dichloromethane (CH₂Cl₂). A solution of BBr₃ (12.8 mL, 12.80 mmol) was added dropwise under a nitrogen atmosphere at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h, and the completion of the reaction was confirmed by TLC. Subsequently, 10 mL of MeOH was added, and stirring continued for 30 min. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting solid was washed five times with CH₂Cl₂ (100 mL each), and then dried under vacuum to yield 2,3,9,10-tetrahydroxyberberine in 99% yield (1.09 g, 2.98 mmol). ALT001 (750 µM) was administered in combination with paclitaxel with EtOH as the vehicle.

Measurement of mitophagy levels in C4da neurons

To assess mitophagy levels in C4da neurons of Drosophila larvae treated with ALT001, we utilized the pH-sensitive fluorescent probe mitochondria-targeted Keima (mt-Keima), following previously established protocols19,20 and imaged using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope with a C-Apochromat 40x/1.20 W Korr M27 lens at the Neuroscience Translational Research Solution Center (Busan, South Korea). The fluorescence signal of mt-Keima was acquired by applying two sequential excitation wavelengths (458 nm and 561 nm) and collecting emitted light in the 595–700 nm spectrum. Quantification of mitophagy levels was performed by analyzing mt-Keima confocal images with Zeiss Zen software, following previously established methods20,21. The proportion of pixels with an increased red/green ratio was utilized to calculate mitophagy percentage. Each experiment was repeated three times independently with at least four images per sample being evaluated in each instance. The results are presented as the means ± SDs.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For quantitative real-time PCR analysis, total RNA was isolated from ten L3 larvae using an easy-BLUE™ Total RNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and cDNA was synthesized using TOPscript™ RT DryMIX (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in triplicate using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Enzynomics) and an ABI Prism 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). rp49 was used as an internal control for all samples, with normalization of gene-specific mRNA levels to the rp49 RNA level. The mRNA levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCΤ-threshold cycle method. For primer pairs, we used rp49-F (5’-GCTTCAAGATGACCATCCGCCC-3’), rp49-R (5’-GGTGCGCTTGTTCGATCCGTAAC-3’), PGC-1α-F (5’-GGAGGAAGACGTGCCTTCTG-3’), PGC-1α-R (5’- TACATTCGGTGCTGGTGCTT-3’), TFAM-F (5’-AACCGCTGACTCCCTACTTTC-3’), TFAM-R (5’- CGACGGTGGTAATCTGGGG-3’), EWG-F (5’- ACGAACAGCGATGGAACAGT-3’), EWG-R (5’-TGCTTAGCAGAGTGGCATCC-3’), ND5-F (5’- GGGTGAGATGGTTTAGGACTTG-3’), ND5-R (5’-AAGCTACATCCCCAATTCGAT-3’), Cyt-B-F (5’- GAAAATTCCGAGGGATTCAA-3’), Cyt-B-R (5’-AACTGGTCGAGCTCCAATTC-3’), COX2-F (5’- GAATCGGCCATCAATGATATTGAAGTTACG-3’), COX2-R (5’-GTTCAAGAATGAATAACATCAGCAGCTG-3’). The experiment was independently repeated three times, and the results are presented as the mean ± SD.

Analysis of C4da neuron dendrites

The structural analysis of C4da neuron dendrites in L3 larvae was conducted based on previously described protocols18,19 using a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) at the Neuroscience Translational Research Solution Center. To determine the dendritic structure of C4da neurons at abdominal segment A4 of L3 larvae, images of the fluorescent plasma membrane marker CD4-tdTomato (CD4-tdTom)51 were obtained by confocal microscopy. Confocal image stacks of C4da neuron dendrites were converted to maximum intensity projections using Zeiss Zen software. Dendrite length and the number of dendritic branches were analyzed in ImageJ software using the skeleton plugin function (NIH, Bethesda, MD). For each larva, a single C4da neuron from abdominal segment A4 was analyzed for its dorsal projection, with at least 13 larvae examined in each genotype group. The results are presented as the mean values with the SDs.

Thermal nociception assays

Heat hypersensitivity caused by paclitaxel was analyzed using thermal nociception assays conducted based on previously described protocols18,19. Briefly, L3 larvae (120 h after egg laying [AEL]) were briefly rinsed with distilled water and gently transferred onto a Petri dish. After an acclimation period of 10 s, the abdominal segments A4–A5 were stimulated under a microscope using a custom-designed 0.6 mm-wide thermal probe, whose temperature was regulated by a microprocessor. The latency to elicit the aversive corkscrew-like rolling behavior was recorded as the withdrawal latency, with a maximum cut-off time of 20 s. Larvae that failed to exhibit a rolling response within 20 s were classified as non-responders. A minimum of 50 larvae were tested per assay, with results presented as mean ± SD.

Following the thermal nociception assay, larval size was assessed by capturing images using a dissection microscope (OLYMPUS MVX10, Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan). The larval area was subsequently measured using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). At least 30 larvae were analyzed per genotype, and the results are expressed as mean values with standard deviations (SD).

Mouse experiments

Healthy 6-week-old C57BJ mice were acquired from SAMTAKO Bio Korea (Osan, Gyeonggi, Korea), and maintained under controlled conditions, including a 12 h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. All experimental procedures were approved by the Dong-A Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (DIACUC-16-15) and conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All in vivo animal experiments were performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). After one week of adaptation, mice were injected intraperitoneally with paclitaxel (16 mg/kg, 5% DMSO in PBS) either alone or in combination with ALT001 (10 mg/kg, 5% DMSO, 10% Tween 80 in DW), four times every four days, and mechanical allodynia was assessed using the von Frey test on day 16. The vehicle control animals received the same vehicle formulation (5% DMSO and 10% Tween 80 in distilled water) as the treatment group, and all procedures were conducted in a blinded manner.

Von Frey tests

Mechanical sensitivity was determined using a series of von Frey filaments (0.16, 0.6, 1, 1.4, 2, and 4 g; Stoelting, IL, USA; North Coast Medical, Morgan Hill, CA, USA) following the “up-and-down” or “ascending stimuli” method as previously established52. The mice were acclimated in a glass panel box placed on a platform with a metal mesh floor, which allowed free access to the plantar surface of the paw for 30 min. Calibration was performed by initially applying a 4 g von Frey filament (Stoelting, IL, USA). Mice were placed inside an acrylic box equipped with a mesh floor, which permitted access to the plantar side of the paw or testing. After a 30-minute habituation period, the filaments were gently applied to the mid-plantar surface of the hind paw via the mesh floor. The testing protocol started with the lowest filament force (0.6 g). If no response was observed, higher forces were applied. The force that elicited a 60% response–defined as paw withdrawal, licking, or toe clenching with shaking–was recorded as the withdrawal threshold. Each force level was tested five times with a 5-minute interval between applications. The final threshold value was calculated by averaging the five measurements. The data were compiled using GraphPad Prism 9 (Boston, MA, USA) and analyzed statistically.

Analysis of IENF in the footpads

After euthanasia, foot pad tissues from the plantar surface of the hind paws were collected and fixed in Zamboni fixative (Newcomer Supply, WI, USA) at 4 °C for one day. After fixation, the tissues were washed three times with PBS and stored in 20% sucrose for two days for cryoprotection. The footpad tissues were then cryosectioned at a thickness of 50 μm and subsequently fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde. The tissue sections were subjected to sequential washes with PBS, PBS-T (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS), and a final PBS rinse, before being blocked in 5% FBS for 1 h at room temperature. To detect PGP9.5, blocked sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a 1:1,000 diluted primary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Following three PBS washes, they were treated for 2 h at room temperature with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000; Invitrogen, MA, USA). The sections underwent three PBS washes before being incubated in the dark for 2 h with an Alexa 488-labeled rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:500, Invitrogen, A21206) for nuclear staining. The stained tissues were then mounted using Antifade Mounting Medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) to protect sample integrity.

For IENF analysis, five plantar skin sections were selected from each animal, with three random sites per section chosen for evaluation. Fluorescence images were acquired using an ApoTome2 fluorescence microscope equipped with an AxioImager 2 (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) at the Neuroscience Translational Research Solution Center (Busan, South Korea). Imaging was performed using the Z-stack tool, which captured 19 images at 10 μm intervals at 200x magnification. Nerve fibers with peripheral endings extending from the dermis to the epidermis were counted. Peripheral endings that appeared only in the epidermis or dermis were excluded from the analysis. The results were normalized to the total length of the dermal–epidermal boundary and analyzed using ImageJ/Fiji software.

Clonogenic survival assay

A clonogenic survival assay was conducted following previously established protocols53, while A549 lung cancer and MCF7 breast cancer cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; JR Scientific Inc., Woodland, CA, USA). For the paclitaxel survival assay, 5 × 10² cells were plated in a 60 mm dish and incubated for one day with different concentrations of paclitaxel, with or without ALT001 (15 µM), followed by three PBS washes. After incubation for 10–12 days, colonies were fixed, stained with methylene blue, and counted. All survival experiments were conducted in duplicate or triplicate, with results expressed as mean values ± SD.

Statistical analysis

Differences between two groups were assessed using Student’s t-test, whereas statistical comparisons among three or more groups were conducted using one-way or two-way ANOVA with the Šidák correction. Survival curves were statistically analyzed using the log-rank test. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05 and All statistical tests were carried out in Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zajaczkowska, R. et al. Mechanisms of Chemotherapy-Induced peripheral neuropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1451 (2019).

Klein, I. & Lehmann, H. C. Pathomechanisms of Paclitaxel-Induced peripheral neuropathy. Toxics 9, 229 (2021).

Miaskowski, C. et al. Impact of chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicities on adult cancer survivors’ symptom burden and quality of life. J. Cancer Surviv. 12, 234–245 (2018).

Park, S. B. et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: A critical analysis. CA Cancer J. Clin. 63, 419–437 (2013).

Seretny, M. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and predictors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 155, 2461–2470 (2014).

Areti, A., Yerra, V. G., Naidu, V. & Kumar, A. Oxidative stress and nerve damage: Role in chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy. Redox Biol. 2, 289–295 (2014).

Wang, X. M., Lehky, T. J., Brell, J. M. & Dorsey, S. G. Discovering cytokines as targets for chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Cytokine 59, 3–9 (2012).

Fukuda, Y., Li, Y. & Segal, R. A. A mechanistic understanding of axon degeneration in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Front. Neurosci. 11, 481 (2017).

Coleman, M. P. & Hoke, A. Programmed axon degeneration: From mouse to mechanism to medicine. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 183–196 (2020).

Park, S. B. et al. Axonal degeneration in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: Clinical and experimental evidence. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 94, 962–972 (2023).

Shin, G. J. et al. Integrins protect sensory neurons in models of paclitaxel-induced peripheral sensory neuropathy. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118 (2021).

Ertilav, K., Naziroglu, M., Ataizi, Z. S. & Yildizhan, K. Melatonin and selenium suppress docetaxel-induced TRPV1 activation, neuropathic pain and oxidative neurotoxicity in mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 199, 1469–1487 (2021).

Jiang, X. S. et al. PINK1/Parkin mediated mitophagy ameliorates palmitic acid-induced apoptosis through reducing mitochondrial ROS production in podocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 525, 954–961 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. PTEN-Induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin-Mediated mitophagy protects PC12 cells against Cisplatin-Induced neurotoxicity. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 8797–8806 (2019).

Zhao, G. et al. Parkin-mediated mitophagy is a potential treatment for oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 326, C214–C228 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. SIRT3 alleviates painful diabetic neuropathy by mediating the FoxO3a-PINK1-Parkin signaling pathway to activate mitophagy. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 30, e14703 (2024).

Um, J. H. et al. Selective induction of Rab9-dependent alternative mitophagy using a synthetic derivative of isoquinoline alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction and cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease models. Theranostics 14, 56–74 (2024).

Jang, H. J., Kim, Y. Y., Lee, K. M., Shin, J. E. & Yun, J. The PINK1 Activator Niclosamide Mitigates Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Thermal Hypersensitivity in a Paclitaxel-Induced Drosophila Model of Peripheral Neuropathy. Biomedicines 10 (2022).

Kim, Y. Y. et al. PINK1 alleviates thermal hypersensitivity in a paclitaxel-induced Drosophila model of peripheral neuropathy. PLoS One. 15, e0239126 (2020).

Kim, Y. Y. et al. Assessment of mitophagy in mt-Keima Drosophila revealed an essential role of the PINK1-Parkin pathway in mitophagy induction in vivo. FASEB J. 33, 9742–9751 (2019).

Sun, N. et al. Measuring in vivo mitophagy. Mol. Cell. 60, 685–696 (2015).

Haussmann, I. U., White, K. & Soller, M. Erect wing regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila by integration of multiple signaling pathways. Genome Biol. 9, R73 (2008).

Brazill, J. M., Cruz, B., Zhu, Y. & Zhai, R. G. Nmnat mitigates sensory dysfunction in a Drosophila model of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Dis Model. Mech 11 (2018).

Onishi, M., Yamano, K., Sato, M., Matsuda, N. & Okamoto, K. Molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of mitophagy. EMBO J. 40, e104705 (2021).

Saito, T. et al. An alternative mitophagy pathway mediated by Rab9 protects the heart against ischemia. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 802–819 (2019).

Lucarini, E. et al. Broad-spectrum neuroprotection exerted by DDD-028 in a mouse model of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Pain 164, 2581–2595 (2023).

Meregalli, C. et al. Human intravenous Immunoglobulin alleviates neuropathic symptoms in a rat model of Paclitaxel-Induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Int J. Mol. Sci 22 (2021).

Boyette-Davis, J. A., Walters, E. T. & Dougherty, P. M. Mechanisms involved in the development of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Pain Manag. 5, 285–296 (2015).

Han, Y. & Smith, M. T. Pathobiology of cancer chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). Front. Pharmacol. 4, 156 (2013).

Cen, X. et al. Pharmacological targeting of MCL-1 promotes mitophagy and improves disease pathologies in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Nat. Commun. 11, 5731 (2020).

Fang, E. F. et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-beta and Tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 401–412 (2019).

Xie, C. et al. Amelioration of Alzheimer’s disease pathology by mitophagy inducers identified via machine learning and a cross-species workflow. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 76–93 (2022).

Yildizhan, K. & Naziroglu, M. Glutathione depletion and parkinsonian neurotoxin MPP(+)-Induced TRPM2 channel activation play central roles in oxidative cytotoxicity and inflammation in microglia. Mol. Neurobiol. 57, 3508–3525 (2020).

Palikaras, K., Lionaki, E. & Tavernarakis, N. Mechanisms of mitophagy in cellular homeostasis, physiology and pathology. Nat. Cell. Biol. 20, 1013–1022 (2018).

Klemmensen, M. M., Borrowman, S. H., Pearce, C., Pyles, B. & Chandra, B. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Neurotherapeutics 21, e00292 (2024).

Rose, J. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in glial cells: Implications for neuronal homeostasis and survival. Toxicology 391, 109–115 (2017).

Doyle, T. M. & Salvemini, D. Mini-Review: mitochondrial dysfunction and chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. Neurosci. Lett. 760, 136087 (2021).

Khuankaew, C., Sawaddiruk, P., Surinkaew, P., Chattipakorn, N. & Chattipakorn, S. C. Possible roles of mitochondrial dysfunction in neuropathy. Int. J. Neurosci. 131, 1019–1041 (2021).

Maj, M. A., Ma, J., Krukowski, K. N., Kavelaars, A. & Heijnen, C. J. Inhibition of mitochondrial p53 accumulation by PFT-mu prevents Cisplatin-Induced peripheral neuropathy. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10, 108 (2017).

Park, J. Y. et al. Mitochondrial swelling and microtubule depolymerization are associated with energy depletion in axon degeneration. Neuroscience 238, 258–269 (2013).

Xiao, W. H. et al. Mitochondrial abnormality in sensory, but not motor, axons in paclitaxel-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat. Neuroscience 199, 461–469 (2011).

Zheng, H., Xiao, W. H. & Bennett, G. J. Mitotoxicity and bortezomib-induced chronic painful peripheral neuropathy. Exp. Neurol. 238, 225–234 (2012).

Xiao, W. H. & Bennett, G. J. Effects of mitochondrial poisons on the neuropathic pain produced by the chemotherapeutic agents, Paclitaxel and oxaliplatin. Pain 153, 704–709 (2012).

Itoh, K., Shimoyama, M., Schiller, P. W. & Toyama, S. Protective effect of a mitochondria-targeting peptide against paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 101, 1012–1018 (2023).

LoCoco, P. M. et al. Pharmacological augmentation of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) protects against paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Elife 6 (2017).

Zheng, H., Xiao, W. H. & Bennett, G. J. Functional deficits in peripheral nerve mitochondria in rats with paclitaxel- and oxaliplatin-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy. Exp. Neurol. 232, 154–161 (2011).

Pickles, S., Vigie, P. & Youle, R. J. Mitophagy and quality control mechanisms in mitochondrial maintenance. Curr. Biol. 28, R170–R185 (2018).

Hirota, Y. et al. Mitophagy is primarily due to alternative autophagy and requires the MAPK1 and MAPK14 signaling pathways. Autophagy 11, 332–343 (2015).

Nishida, Y. et al. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature 461, 654–658 (2009).

Shao, S. et al. Divanillyl sulfone suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation via inducing mitophagy to ameliorate chronic neuropathic pain in mice. J. Neuroinflammation. 18, 142 (2021).

Han, C., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. Enhancer-driven membrane markers for analysis of nonautonomous mechanisms reveal neuron-glia interactions in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 108, 9673–9678 (2011).

Deuis, J. R., Dvorakova, L. S. & Vetter, I. Methods used to evaluate pain behaviors in rodents. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10, 284 (2017).

Yun, J., Zhong, Q., Kwak, J. Y. & Lee, W. H. Hypersensitivity of Brca1-deficient MEF to the DNA interstrand crosslinking agent mitomycin C is associated with defect in homologous recombination repair and aberrant S-phase arrest. Oncogene 24, 4009–4016 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant of the Korea Dementia Research Project through the Korea Dementia Research Center (KDRC), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare and Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2024-00335192) (to J.Yun) and by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (grant number: RS-2025-00554128) (to J.Yun), (grant number: 2016R1A5A2007009 and 2017R1C1B5014853) (to J.H. Lee) and by the Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (grant number: 2021R1A6C101A425).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. H. Cho, J. H. Lee and J. Yun conceptualized the study. S. Im, S. M. Choi, and Y. Y. Kim performed the experiments and interpreted the data. D. J. Jeong, J. H. Um, K. M. Kim and E. Yoo conceived the specific experiments. S. Im, J. H. Lee and J. Yun wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided editorial input.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S. Im, S. M. Choi, J. H. Choi, J. H. Lee, and J. Yun have filed a patent about the treatment of CIPN using a mitophagy inducer. E. Yoo, J. H. Cho and J. Yun are co-founders of Altmedical co. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Im, S., Choi, S.M., Kim, Y.Y. et al. A novel isoquinoline mitophagy inducer ameliorates paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in Drosophila and mouse models. Sci Rep 15, 20960 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04178-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04178-y