Abstract

Metal oxides such as Zinc Oxide (ZnO) and Cerium Oxide (CeO2) have emerged as promising materials for electrochemical sensing due to their redox activity, surface charge sensitivity, and chemical stability. We report the direct printing of ZnO and CeO2 nanostructures on flexible screen-printed electrodes using an atmospheric plasma-aided technique, enabling binder-free printing from aqueous suspensions. The electrochemical sensing ability of ZnO was tested for pH sensing, while CeO2 was tested for non-enzymatic Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) detection. Morphological and optical characterizations revealed voltage-dependent variations in nanoparticle distribution, thickness, and bandgap, with improved layer uniformity and substrate adhesion at higher plasma voltages. Electrochemical characterization demonstrated enhanced charge transfer and sensitivity, with ZnO showing a maximum pH response of 34.96 mV/pH when fabricated at 18 kV and CeO2 reaching a peak H2O2 sensitivity of 1.03 µA/µM/cm² when fabricated at 24 kV. Our results establish plasma-assisted printing as a binder free, rapid, low-temperature method for directly printing high-performance metal oxide sensors on flexible polymer substrates for wearable applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal oxides have garnered significant attention for chemical and biosensing applications due to their inherent redox activity, surface charge modulation, and stable semiconducting behavior1,2,3. Materials such as Zinc Oxide (ZnO), Cerium Oxide (CeO2), Tin Oxide (SnO2), Titanium Dioxide (TiO2), and Iron Oxide (Fe2O₃) are widely employed in electrochemical sensing platforms for their chemical robustness, high density of oxygen vacancies, and ability to facilitate surface-mediated charge transfer reactions4,5,6,7,8. These oxides support fast electron exchange reactions and exhibit excellent compatibility with screen-printed and miniaturized electrodes, making them especially attractive for the scalable fabrication of compact, low-cost, and disposable sensor platforms9,10,11,12,13.

Notable examples of metal oxide-based sensors include ZnO for pH and UV sensing6,14,15,16,17,18, SnO2 for Methane, Carbon Monoxide, and Hydrogen detection19,20,21, TiO2 for Ammonia and Nitrogen Dioxide monitoring22,23, Fe2O₃ for Ethanol and Acetone sensing24,25, and CeO2 for non-enzymatic Hydrogen Peroxide detection26. Other metal oxides, including CuO for Ammonia27, MnO2 for heavy metal ions28, NiO for Urea and Ethanol29, and ZrO2 for Oxygen detection30 further exemplify the chemical selectivity and application range of this material class. Collectively, these examples underscore the versatility of metal oxides in electrochemical and gas sensing, often enabling target-specific detection through intrinsic material properties without the need for complex surface modification.

Conventional metal oxide deposition techniques such as chemical vapor deposition, hydrothermal growth, sol-gel synthesis, and electrodeposition pose significant limitations for scalable sensor fabrication due to their reliance on high processing temperatures (typically 200–500 °C), prolonged reaction times, and the use of binders or chemical additives that can interfere with electrochemical performance31,32,33. These approaches also require post-deposition treatments like annealing to ensure structural integrity, which adds both complexity and cost. Moreover, such conditions are often incompatible with flexible or disposable substrates like PET, paper, or polymer-based Screen Printed Electrodes (SPEs) used in modern wearable and point-of-care devices34. Even techniques like drop casting and conventional inkjet printing offer ease of use but tend to suffer from poor film uniformity, weak adhesion, and lack of repeatability, especially under wet testing conditions, where the deposited films often delaminate or dissolve35,36,37,38.

Recent advances underscore the need for scalable, low-temperature techniques that can directly deposit sensing materials onto functional electrodes without the need for complex post-processing or high-temperature annealing34,39. Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) methods have gained attention for enhancing surface adhesion, functionalization, and catalytic performance at substrate temperatures below 100 °C; however, existing studies typically use plasma treatment only after deposition techniques like electrodeposition or screen printing, resulting in sequential processes that lack real-time material activation39,40. Other fabrication strategies, such as wet-chemical growth or multi-step assembly on paper or flexible substrates, often involve lengthy procedures and offer limited control over structural features41,42. While these approaches offer useful insights, they do not provide a fully integrated, one-step printing and activation process of metal oxide nanostructures. This gap highlights the need for a unified method capable of rapid, binder-free deposition with tunable performance on scalable, low-cost platforms.

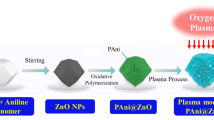

To overcome the constraints associated with conventional film fabrication techniques, such as high annealing temperatures, extended processing times, and the use of chemical binders, plasma-assisted printing has emerged as an efficient, low-temperature method for direct nanoparticle deposition43,44. This approach utilizes an atmospheric plasma jet to aerosolize nanoparticle suspensions and deposit them onto the substrate, where the plasma simultaneously facilitates activation, surface functionalization, and uniform deposition (Fig. 1a). Unlike traditional approaches, plasma-assisted printing eliminates the need for post-deposition thermal sintering or solvent-based treatments, making it particularly suitable for use with flexible or temperature-sensitive substrates45,46,47,48,49.

The versatility of this technique has been demonstrated across a wide range of materials, including metal oxides such as ZnO, TiO2, SnO2, and CuO, which have been successfully printed onto substrates like glass, silicon, polyimide, and PET50,51,52. Plasma exposure enhances nanoparticle activation, surface coverage, and electrical performance while also modifying the substrate surface to form a thin, nanoporous foundation layer that significantly improves film adhesion and interfacial bonding; comparative studies consistently show that plasma printed samples exhibit superior conductivity, uniformity, and structural integrity compared to plasma-off conditions- all without requiring post-deposition annealing48. These capabilities make plasma-assisted printing an attractive platform for fabricating binder-free, durable, and reproducible sensing layers for applications in wearables, environmental monitoring, and point-of-care electrochemical devices.

(a) Schematic illustration of plasma-aided inkjet printing of metal oxide nanostructures onto a screen-printed electrode for electrochemical sensing applications, (b) Top-view SEM image showing nanoparticle size and surface distribution of the plasma-printed Zinc Oxide (ZnO) layer, (c) Cross-sectional SEM micrograph highlighting the thickness and internal structure of the printed Zinc Oxide (ZnO) layer.

In this study, Zinc Oxide (ZnO) and Cerium Oxide (CeO2) were selected as functional metal oxide materials for the development of electrochemical pH and Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) sensors, respectively. Both nanomaterials were deposited onto commercial carbon-based Screen-PrintedElectrodes (SPEs) using a plasma-assisted inkjet printing technique, enabling low-temperature, additive, and binder-free fabrication of uniform sensing layers (Fig. 1b, c). ZnO has been widely used in pH sensing applications due to its high isoelectric point, surface charge sensitivity, and biocompatibility. These properties make it well suited for monitoring pH in body fluids such as sweat (pH 4.5–6.5, up to 9 in cystic fibrosis), urine (pH 4.5-8.0), saliva (pH 6.2–7.6), and tear fluid (pH 6.5–7.6), where deviations can indicate metabolic disorders, infections, or systemic conditions53,54.

Cerium Oxide (CeO2) is widely recognized for its strong redox behavior, which is governed by the reversible transition between Ce³⁺ and Ce⁴⁺ oxidation states1,55. This property allows CeO2 to act as a redox-active material in sensing platforms, particularly for the non-enzymatic detection of Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2), a key biomarker in oxidative stress and metabolic monitoring56. The redox cycling enables rapid electron exchange, mimicking peroxidase-like catalytic behavior and enhancing electrochemical reactivity toward H2O2 reduction. Due to its Oxygen storage capacity, chemical stability, and catalytic functionality, CeO2 has been extensively explored as an alternative to enzymatic sensing layers in electrochemical systems57,58.

This study presents a proof-of-concept demonstration of direct plasma-assisted inkjet printing to fabricate electrochemical sensing layers using ZnO and CeO2 nanoparticles. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report where nanoparticle deposition and plasma activation are performed simultaneously in a single step for metal oxide-based electrochemical sensor fabrication. Well-established materials, ZnO for pH and CeO2 for H2O2 detection, were chosen to evaluate the effectiveness of the method under relevant sensing conditions. Aqueous nanoparticle suspensions were printed at varying plasma voltages onto carbon-based SPEs. The resulting electrodes were systematically characterized using SEM, UV-Vis spectroscopy, Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), and Open Circuit Potential (OCP) measurements. The results validate the feasibility of scalable, in situ printed metal oxide sensors suitable for flexible and wearable electrochemical applications.

Materials and methods

Materials used

All chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade. Cerium Oxide nanoparticles (CeO2 NPs) were synthesized via a chemical precipitation method. Zinc Oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs, 99.99% purity; 30–40 nm) were purchased from US Research Nanomaterials for electrode modification. Potassium Ferricyanide [K₃[Fe(CN)₆]] (15 mM and 5 mM) and 0.1 M Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Solutions of Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) at concentrations of 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, and 72 µM were prepared using deionized (DI) water. Apera standard pH buffer solutions (pH 4, 7, and 10.1) were used for ZnO sensor testing. Zensor Screen Printed Electrodes (TE100) were obtained from CH Instruments for electrode modification and electrochemical measurements.

Plasma-aided printing of ZnO and CeO2 nanostructures

The ZnO and CeO2 sensing nanostructure layers were fabricated using a plasma-assisted inkjet printing technique with a low-temperature atmospheric plasma printer (Space Foundry Inc., USA). For ZnO, the nanoparticle suspension was prepared by diluting ZnO nanoparticles (99.99% purity; 30–40 nm, US Research Nanomaterials) in a 1:20 ratio with deionized (DI) water. For CeO2, a suspension was prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/mL in DI water. Both suspensions were directly deposited onto previously cleaned commercial SPEs (TE100; 3-electrode configuration), with deposition confined to the working electrode area.

Printing was carried out using a plasma stream composed of 95% Argon and 5% Hydrogen, which simultaneously atomized and activated the nanoparticle suspension, promoting improved adhesion and uniform layer formation. The deposition was performed at a constant print speed of 30 mm/min, with the plasma voltage varied to fabricate different samples: 16 kV, 18 kV, and 20 kV for ZnO; and 22 kV, 24 kV, and 26 kV for CeO2. All other printing parameters were held constant, including a plasma frequency of 30 kHz, a mist level of 45%, and a printhead-substrate distance of 1 mm. Gas flow rates were maintained at 150 SCCM for the wet aerosol and 300 SCCM for the dry inert gas at 20 psi. Each sample underwent a pre-plasma surface treatment (plasma exposure without nanoparticle suspension) followed by a single-layer print pass.

Characterization of ZnO and CeO2 nanostructures

The surface morphology of plasma-printed ZnO and CeO2 nanostructure layers was analyzed using a JEOL JSM-6060 scanning electron microscope (SEM). To enable high-resolution imaging and cross-sectional analysis, nanoparticle suspensions were deposited on silicon wafers coated with a layer of electrochemical-grade conductive carbon paste. The carbon layer was screen-printed onto the silicon wafer and thermally cured to mimic the surface properties of the carbon-based SPEs, ensuring that the printed nanostructures experienced a similar deposition environment. SEM imaging was performed on these carbon-coated silicon substrates after plasma printing at different voltages. Optical properties of the ZnO and CeO2 nanostructure layers were examined using an Ocean Optics FLAME-S-XR1-ES UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer, with absorption spectra used to estimate the optical bandgap based on characteristic UV absorption features.

Electrochemical measurement setup

For electrochemical measurements, the printed nanostructure layers on SPEs were used as the working electrode in a three-electrode cell setup, with an Ag/AgCl (saturated KCl) reference electrode and a platinum wire as the counter electrode. All measurements were conducted using a Palmsens EmStat3 potentiostat at room temperature (25 °C). The working electrodes were tested in buffer solutions of varying concentrations of 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, and 72 µM Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) to evaluate the current response and electrocatalytic activity of CeO2 nanoparticles towards the detection of H2O2. Similarly, the ZnO working electrodes were immersed in different standard buffer solutions to assess their pH sensitivity.

The pH sensitivity of the ZnO sensors was evaluated by measuring the OCP at various pH values in Apera standard pH buffer solutions (pH 4, 7, and 10.1). The OCP values were recorded after a stabilization period of 30 s for each pH level. The sensitivity of the ZnO sensors was calculated as the slope of the potential versus pH plot, in mV/pH.

Results and discussion

In this study, we explored the direct plasma-aided inkjet printing of ZnO and CeO2 metal oxide structures from their respective nanoparticle precursor suspensions. The ability to print metal oxide nanostructures using this technique offers significant advantages in terms of precision, scalability, and controlled deposition. The structural characteristics of these printed metal oxides are intrinsically linked to the plasma printing conditions, particularly the applied voltage, which influences nanoparticle size, morphology, and layer thickness. Furthermore, the printed structures demonstrated stable and repeatable ion sensing properties, highlighting their potential for electrochemical applications.

Influence of plasma printing on the morphology of ZnO and CeO2 nanostructures

The morphology of ZnO and CeO2 nanostructures deposited via plasma-aided inkjet printing was analyzed using a JEOL JSM-6060 scanning electron microscope (SEM) at 4000× magnification to compare their structural characteristics with those obtained from conventional drop-cast nanoparticle suspension. The SEM analysis revealed that drop-cast samples exhibited a non-uniform distribution of nanoparticles, with smaller particles forming dispersed smooth clusters across the substrate. In contrast, plasma-printed samples demonstrated a rougher arrangement with improved nanoparticle adhesion, forming porous and more structured aggregates composed of nanoscale primary particles. These differences in deposition quality highlight the role of plasma-assisted printing in facilitating controlled nanoparticle deposition, leading to structures with enhanced uniformity and stability.

Drop-cast ZnO samples formed relatively smooth and densely packed clusters, with an average nanoparticle aggregate size of 250 ± 145 nm (Fig. 2a). In contrast, plasma-printed ZnO samples exhibited a distinctly more porous morphology across all tested plasma voltages. At 16 kV, the ZnO nanoparticles aggregated into loosely connected structures with an average nanoparticle aggregate size of 580 ± 180 nm (Fig. 2b). Although the overall porosity remained relatively consistent across the 16–20 kVrange, a clear trend of increasing nanoparticle aggregate size was observed with rising plasma voltage. At 18 kV, the average nanoparticle aggregate size increased to 650 ± 200 nm (Fig. 2c) and further grew to 750 ± 170 nm at 20 kV (Fig. 2d).

The enhanced plasma energy at higher voltages promotes nanoparticle mobility and surface interactions, resulting in the formation of larger aggregates composed of primary nanoscale particles, while preserving the overall porous framework. This porous and interconnected morphology, along with increased surface roughness, is particularly beneficial for electrochemical pH sensing, as it facilitates greater electrolyte access, enhances the surface-to-volume ratio, and provides more electroactive sites,ultimately improving sensitivity and signal stability.

SEM images showing the surface morphology and aggregate distribution of ZnO and CeO2 nanostructures before and after plasma-assisted printing: (a) ZnO precursor suspension, (b) ZnO printed at 16 kV, (c) ZnO printed at 18 kV, (d) ZnO printed at 20 kV, (e) CeO2 precursor suspension, (f) CeO2 printed at 22 kV, (g) CeO2 printed at 24 kV, and (h) CeO2 printed at 26 kV.

Drop-cast CeO2 samples exhibited large, irregularly shaped agglomerates, with an average nanoparticle aggregate size of 810 ± 273 nm (Fig. 2e). These clusters formed due to uncontrolled nanoparticle aggregation during solvent evaporation, resulting in densely packed structures. In contrast, plasma-aided deposition produced more spatially separated and uniform nanoparticle aggregates, avoiding the dense agglomeration seen in drop-cast samples. At 22 kV, CeO2 nanoparticles formed relatively small and well-dispersed aggregates with an average size of 650 ± 242 nm (Fig. 2f). Although larger than the individual nanoparticles in the precursor suspension, these aggregates displayed improved uniformity and spatial control. Increasing the plasma voltage to 24 kV led to a broader size distribution, where both small and noticeably larger aggregates coexisted, averaging 940 ± 333 nm (Fig. 2g). At 26 kV, larger and more compact clusters dominated the surface, reaching 970 ± 373 nm in size (Fig. 2h). These structures consist of secondary aggregates formed from nanoscale CeO2 particles (< 100 nm), which undergo coalescence during the plasma-assisted printing process. The observed sizes reflect the dimensions of these aggregates rather than individual nanoparticles. This voltage-dependent aggregation behavior is reflected in the progressive increase in average size, as summarized in Table 1. Additional low-magnification SEM images of ZnO and CeO2 are provided in thesupplementary materials (Figure S1a–h).

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was performed to confirm the elemental composition of the plasma-printed samples. The EDS spectra verified the presence of Zinc and Oxygen in the ZnO sample (Figure S2a), and Cerium and Oxygen in the CeO2 sample (Figure S2b), indicating successful deposition of the intended metal oxide layers without detectable contamination. Corresponding SEM analysis revealed that plasma exposure induced aggregation and surface restructuring of primary nanoparticles, leading to an increase in apparent particle size due to plasma-driven aggregation and surface interaction effects. A progressive increase in aggregate size was observed with increasing plasma voltage, suggesting that higher plasma energy promotes coalescence and structural reorganization during deposition. Compared to the non-uniform and loosely packed morphology observed in drop-cast samples, plasma-printed structures exhibited enhanced structural integrity and uniformity. These findings highlight the capability of plasma-aided inkjet printing to produce well-defined nanostructures with improved adhesion and material properties for sensing applications.

Surface morphology and structural transformations

Cross-sectional SEM analysis provided further insight into the influence of plasma-aided printing on layer thickness and deposition characteristics. Drop-cast ZnO samples exhibited thick, compact layers due to uncontrolled nanoparticle stacking during solvent evaporation, with an average thickness of 3.38 ± 0.2 μm (Fig. 3a). In contrast, plasma-printed ZnO layers were thinner and showed increase in thickness with rising plasma voltage. At 16 kV, the ZnO layer measured 1.01 ± 0.4 μm (Fig. 3b), increasing to 1.21 ± 0.27 μm at 18 kV (Fig. 3c), and reaching 3.01 ± 0.37 μm at 20 kV (Fig. 3d). Notably, the cross-sectional morphology at 20 kV revealed a highly porous structure, indicating that while plasma energy promoted vertical growth, it also enhanced porosity through nanoparticle coalescence and surface restructuring.

A similar voltage-dependent trend was observed in CeO2 samples. The drop-cast CeO2 layer exhibited an average thickness of 2.54 ± 0.46 μm (Fig. 3e), resulting from dense stacking of agglomerated clusters. In contrast, plasma-printed CeO2 layers produced sub-micron thicknesses, with values of 0.53 ± 0.27 μm at 22 kV (Fig. 3f), 0.59 ± 0.16 μm (Fig. 3g) at 24 kV, and 0.67 ± 0.22 μm at 26 kV (Fig. 3h). This reduction in overall thickness, combined with the uniform deposition pattern, suggests that plasma treatment allows for better control over material placement and adhesion, reducing excessive accumulation and promoting more compact nanostructures. These results underscore the capability of plasma-aided inkjet printing to precisely tune layer thickness and morphology through voltage control, enabling the fabrication of uniform, adherent, and structurally optimized nanostructured layers (Table 1).

Cross-sectional SEM images showing the layer thickness of printed ZnO and CeO2 coating composed of nanostructured aggregates: (a) ZnO precursor suspension, (b) ZnO printed at 16 kV, (c) ZnO printed at 18 kV, (d) ZnO printed at 20 kV, (e) CeO2 precursor suspension, (f) CeO2 printed at 22 kV, (g) CeO2 printed at 24 kV, and (h) CeO2 printed at 26 kV.

The adhesion behavior of the deposited nanostructures varied significantly between drop-cast and plasma-printed samples. Drop-cast ZnO and CeO2 layers showed poor adhesion, with delamination and peeling observed under SEM, especially in regions where nanoparticles had formed loosely bound agglomerates. In contrast, plasma-printed samples exhibited markedly improved adhesion, with ZnO at 20 kV and CeO2 at 26 kV demonstrating the strongest interfacial bonding. This enhanced adhesion is attributed to the effect of plasma energy, which not only facilitates nanoparticle restructuring but also modifies the substrate surface at the nanoscale.

During plasma-aided deposition, the high-energy plasma partially penetrates the substrate surface, typically a few nanometers deep, creating a nanoporous, activated layer. This interfacial layer acts as a foundation, enabling the deposited nanoparticles to embed more effectively into the substrate. As a result, even though the printed structures remain porous at higher voltages, the underlying interface becomes stronger, leading to significantly better adhesion. With increasing plasma voltage, this effect becomes more pronounced, explaining the superior adhesion observed in high-voltage plasma-printed samples compared to the weakly bound drop-cast layers.

Optical properties and bandgap analysis of precursor and plasma-printed ZnO and CeO2 structures

Optical studies of ZnO and CeO2 nanoparticles were performed using an Ocean Optics FLAME-S-XR1-ES UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer to investigate their absorption behavior and estimate optical bandgap energies. Plasma-printed ZnO samples, deposited on quartz wafers at 16 kV, 18 kV, and 20 kV, and CeO2 samples printed at 22 kV, 24 kV, and 26 kV, were analyzed across the wavelength range of 250–1000 nm. The absorption spectra correspond to electronic transitions from the valence band to the conduction band and reflect changes in nanoparticle arrangement and crystallinity induced by plasma treatment. Variations in the absorption edge and intensity among the samples indicate that plasma-assisted printing can modulate optical properties through voltage-controlled deposition, offering insight into the structural tuning of nanostructured layers.

The UV-Vis absorption spectra of plasma-printed ZnO samples revealed a characteristic absorption peak associated with the direct bandgap transition of ZnO, with clear variation observed across different plasma voltages. The sample printed at 16 kV exhibited a broad and relatively low-intensity absorption peak centered at 395 nm, indicating weaker optical absorption and possibly a lower degree of nanoparticle connectivity (Fig. 4a). At 18 kV, the peak shifted slightly to 390 nm with increased intensity (Fig. 4b), while the 20 kV sample showed a more pronounced peak at 382 nm (Fig. 4c), suggesting enhanced nanoparticle interaction and improved optical response due to better surface structuring at higher plasma energy.

Tauc plot analysis of the ZnO samples further supported these observations. The estimated bandgap (Eg) was approximately 2.85 eV for both the 16 kV and 18 kV samples (Fig. 4a, b), while the 20 kV sample exhibited a slightly higher bandgap of 2.9 eV (Fig. 4c). This modest increase in Eg, combined with the shift in absorption characteristics, suggests that higher plasma voltages promote improved crystallinity and particle uniformity.

Following the trends observed in ZnO, the UV-Vis absorption spectra of plasma-printed CeO2 samples also exhibited distinct changes with increasing plasma voltage. A consistent absorption peak at 277 nm was observed across all samples (Fig. 5a-c), corresponding to the intrinsic electronic transition of CeO2. However, variations in peak intensity and sharpness reflected differences in structural characteristics. The 22 kV sample showed a relatively small and broader peak, suggesting lower optical density and potential structural disorder (Fig. 5a). In comparison, the 24 kV sample displayed the most intense and well-defined peak, indicating improved nanoparticle interaction and packing (Fig. 5b). At 26 kV, a slight decrease in intensity was noted relative to 24 kV, possibly due to changes in surface morphology or increased light scattering from larger nanoparticle clusters (Fig. 5c).

Tauc plot analysis further revealed variations in optical bandgap (Eg) with plasma voltage. The 22 kV sample exhibited a bandgap of approximately 3.25 eV (Fig. 5a), while both the 24 kV and 26 kV samples showed a higher bandgap of around 3.7 eV (Fig. 5b, c). This trend indicates that increased plasma energy may induce surface and structural modifications, influencing the optical transitions without altering the fundamental electronic structure. The observed shift in Eg and absorption behavior suggests that plasma printing can be used to fine-tune the optical properties of CeO2 nanostructures through controlled processing conditions.

The comparative analysis of plasma-printed ZnO and CeO2 nanostructures reveals that the intrinsic optical transition of CeO2 at 277 nm remains consistent across different plasma voltages, while ZnO gradually approaches its expected transition behavior at higher voltages, with the 20 kV sample showing a peak near 382 nm, close to the typical absorption range of ZnO. Plasma-assisted printing significantly influences their absorption characteristics and bandgap properties. Variations in absorption peak position, intensity, and Tauc plot-derived bandgap energy with increasing plasma voltage indicate that plasma treatment plays a critical role in modifying nanoparticle distribution, surface morphology, and interparticle interactions. For both materials, higher plasma voltages led to enhanced absorption intensity and shifts in the optical bandgap, reflecting changes in nanoparticle compaction, ordering, and possibly crystallinity. These results underscore the capability of plasma-aided inkjet printing not only to enable controlled deposition of metal oxide nanostructures but also to tune their optical and electronic properties through plasma voltage modulation.

Electrochemical sensing properties of plasma-printed metal oxide nanostructure layers

Electrochemical characterization was performed to evaluate the sensing performance of plasma-printed ZnO and CeO₂ nanostructure layers. The study focused on their application in pH and hydrogen peroxide detection, respectively. Plasma-assisted printing enabled the formation of uniform, porous nanostructures with enhanced surface properties suitable for ion sensing and catalytic activity. Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Open Circuit Potential (OCP) measurements were employed to systematically assess their electrochemical behavior under varying plasma printing voltages.

Electrochemical pH sensing using plasma-printed ZnO nanostructure layers

The electrochemical behavior of plasma-printed ZnO nanostructure layers was evaluated using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Open Circuit Potential (OCP) measurements to determine their ion sensitivity and charge transfer efficiency. ZnO is a well-established pH sensor due to its amphoteric nature, making it highly sensitive to H⁺ ions and capable of exhibiting a Nernstian response to pH variations. To assess the electrochemical response of plasma-printed ZnO layers, ZnO nanoparticles were printed onto the working electrode of TE100 carbon-based SPEs at voltages of 16 kV, 18 kV, and 20 kV. The CV measurements were performed in a 5 mM Potassium Ferricyanide electrolyte solution with 0.1 M KCl, while OCP measurements were conducted using three standard pH buffer solutions (pH 4, pH 7, and pH 10.1) to evaluate pH sensitivity.

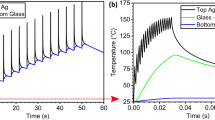

Cyclic voltammograms of plasma-printed ZnO-modified electrodes exhibited well-defined redox peaks, confirming their electrochemical activity. The peak current (Ip) increased with rising plasma voltage, from 52.843 µA at 16 kV to 54.981 µA at 18 kV, reaching 56.210 µA at 20 kV. In comparison, the bare SPE showed a significantly lower peak current of 30.103 µA, indicating the substantial enhancement in charge transfer properties achieved through plasma-assisted printing (Fig. 6a).

The Electrochemically Active Surface Area (EASA) was calculated using the Randles-Sevcik equation, showing a consistent increase with plasma voltage. The EASA values were 0.045 cm² for ZnO nanostructure layers developed with 16 kV, 0.0468 cm² for 18 kV, and 0.0479 cm² for 20 kV, compared to 0.0256 cm² for the bare SPE (Table 2). These results demonstrate that plasma-assisted deposition improves nanoparticle distribution and interconnectivity, enhancing electron transfer kinetics. This increase in EASA is critical for achieving a higher current response and better sensing performance.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms of ZnO deposited SPE electrodes under various plasma voltages of 16 kV, 18 kV, and 20 kV, recorded in 5 mM Potassium Ferricyanide electrolyte with 0.1 M KCl, (b) Cyclic voltammograms of CeO2 deposited SPE electrodes under various plasma voltages of 22 kV, 24 kV, and 26 kV, recorded in 15 mM Potassium Ferricyanide electrolyte.

The pH sensitivity of the ZnO-modified electrodes was further evaluated using OCP measurements in buffer solutions of pH 4, 7, and 10.1. For each plasma voltage condition, a set of three electrodes was fabricated and tested under identical conditions, with more than five repeated measurements per electrode. All plasma-printed ZnO samples exhibited clear and repeatable shifts in potential with increasing pH, confirming their ion-sensitive behavior. The measured OCP values consistently decreased with rising pH across all samples. Specifically, ZnO printed at 20 kV showed a well-defined and stable response, with potentials of 238.47 mV at pH 4, 117.34 mV at pH 7, and 33.65 mV at pH 10.1. Similarly, the 16 kV and 18 kV samples exhibited potentials of 240.12 mV to 42.62 mV and 211.73 mV to 6.73 mV, respectively (Fig. 7a). These results indicate that increasing plasma voltage enhances both the sensitivity and stability of the ZnO-based pH sensing response.

The calculated pH sensitivities were approximately 33.3 mV/pH for ZnO printed at 16 kV, 34.96 mV/pH for 18 kV, and 34.73 mV/pH for 20 kV. The corresponding linearity (R²) values were 0.9913 (16 kV), 0.9974 (18 kV), and 0.9900 (20 kV), with all sensors exhibiting a linear response in the pH range of 4–10.1. Although slightly below the theoretical Nernstian slope, these values reflect strong electrochemical responsiveness typical of nanostructured ZnO-based sensors. Among the samples, ZnO printed at 20 kV exhibited the highest overall sensitivity and a strong linear trend, though ZnO printed at 18 kV showed slightly better linearity across the pH range.

When compared with other ZnO-based pH sensors in the literature (Table 3), the plasma-printed sensors in this work show competitive sensitivity and superior fabrication advantages. For instance, sensors fabricated using RF sputtering and hydrothermal methods have reported sensitivities above 44.56 mV/pH59. These approaches typically require high-temperature annealing, multiple processing steps, or chemical binders. In contrast, our atmospheric plasma-assisted method allows for binder-free, low-temperature (< 100 °C), and maskless deposition, which can be completed in just a few minutes for a standard TE100 working electrode. Additionally, the simultaneous activation and printing process forms a nanoporous foundation layer on the electrode surface, improving interfacial adhesion and enabling robust performance over multiple sensing cycles. This significantly reduces delamination issues often encountered in drop-cast sensors.

Catalytic activity and electrochemical properties of plasma-printed CeO2 nanostructure layers

The electrochemical performance of plasma-printed CeO2-modified electrodes was evaluated using CV to assess their redox behavior and sensing response toward Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2). The electrodes were fabricated by printing CeO2 nanoparticles on TE100 carbon-based SPEs using an atmospheric plasma printer at voltages of 22 kV, 24 kV, and 26 kV. The redox activity, driven by the Ce³⁺/Ce⁴⁺ transition, is crucial to CeO2’s peroxidase-like catalytic behavior and underpins its electrochemical sensing potential.

CV measurements were conducted in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 15 mM Potassium Ferricyanide, with a scan rate of 0.5 V/s. The bare TE100 SPE showed minimal redox response, with a peak current of 30.103 µA and an EASA of only 0.0256 cm², indicating poor charge transfer behavior. In contrast, plasma-printed CeO2-modified electrodes exhibited significant enhancement in peak current values, increasing from 329.692 µA at 22 kV to 420.945 µA at 24 kV, and reaching 434.070 µA at 26 kV (Fig. 6b). The calculated EASA also followed this trend, measured at 0.281 cm² (22 kV), 0.359 cm² (24 kV), and 0.370 cm² (26 kV), indicating improved electroactive surface coverage and higher density of catalytic sites (Table 2).

To evaluate the H2O2 sensing capability, CV was performed in PBS solutions containing varying concentrations of H2O2 ranging from 8 µM to 72 µM (Figure S3a-c). For each plasma voltage condition, a set of three electrodes was fabricated and tested under identical conditions, with more than five repeated measurements per electrode. As the H2O2 concentration increased, the cathodic peak current became more negative, indicating an increase in the catalytic reduction of peroxide at the CeO2 surface. For the 22 kV sample, the current remained relatively unchanged, varying slightly from − 232.996 µA at 8 µM to -232.090 µA at 72 µM, suggesting limited catalytic activity (Table S1). In contrast, the 24 kV sample showed a significant increase in reduction current, from − 271.389 µA to -332.928 µA, while the 26 kV sample exhibited a moderate increase from − 260.028 µA to -279.249 µA across the same concentration range (Fig. 7b).

(a) Open Circuit Potential (OCP) measurements of ZnO-modified electrodes printed with different plasma voltage recorded in standard pH buffer solutions (pH 4, pH 7, and pH 10.1), (b) Cathodic current response of CeO2-modified electrodes at different plasma voltages in the presence of varying H2O2 concentrations.

The sensitivities of the plasma-printed CeO2 electrodes were determined to be 0.15 µA/µM·cm² (22 kV), 1.03 µA/µM·cm² (24 kV), and 0.54 µA/µM·cm² (26 kV). The corresponding linearity values (R²) were 0.3033, 0.9589, and 0.6959, respectively. Among the tested conditions, the 24 kV sample demonstrated the highest sensitivity and strongest linear response, indicating that moderate plasma energy provides optimal nanoparticle activation and uniform layer formation. While the 22 kV sample exhibited lower sensitivity and poor linearity, it still confirmed the baseline catalytic activity of CeO2 without requiring high-temperature processing.

When compared with other CeO2-based H2O2 sensors reported in Table 4, which often rely on drop-casting, electrospinning, or annealing steps and require binders or surfactants, our method presents a significant advancement. The atmospheric plasma-assisted direct printing approach enables single-step, low-temperature, and binder-free fabrication directly onto disposable SPEs. Additionally, the plasma simultaneously modifies the substrate surface to improve nanoparticle adhesion, enhancing mechanical durability and allowing for reliable, repeatable sensing over multiple uses. This streamlined process offers both performance and manufacturing advantages for scalable, non-enzymatic electrochemical H2O2 detection.

Conclusion

This study establishes atmospheric plasma-assisted direct printing as an effective, low-temperature method for fabricating ZnO and CeO2 nanostructured sensing layers on commercial screen-printed electrodes. The process enables simultaneous nanoparticle deposition and plasma activation in a single step, eliminating the need for binders or post-annealing. Plasma treatment enhanced adhesion through the formation of a nanoporous foundation layer and allowed precise control over morphology, thickness, and particle size by adjusting the applied voltage. Electrochemical characterization confirmed reliable pH sensing with ZnO and efficient non-enzymatic H2O2 detection with CeO2, with optimal performance observed at moderate plasma voltages. Compared to traditional fabrication methods, this approach offers improved reproducibility, structural stability, and scalability. These results highlight the potential of plasma-assisted direct printing for the rapid prototyping and deployment of miniaturized, wearable electrochemical sensors.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the Supplementary Information file.

References

Singh, K. R. B., Nayak, V., Sarkar, T. & Singh, R. P. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: properties, biosynthesis and biomedical application. RSC Adv. 10, 27194–27214. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ra04736h (2020).

Aliyana, A. K. et al. Machine learning-assisted ammonium detection using zinc oxide/multi-walled carbon nanotube composite based impedance sensors. Sci. Rep. 11 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03674-1 (2021).

Aliyana, A. K., Ganguly, P., Beniwal, A., Kumar, S. K. N. & Dahiya, R. Disposable pH sensor on paper using Screen-Printed Graphene-Carbon ink modified zinc oxide nanoparticles. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 21049–21056. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2022.3206212 (2022).

Charbgoo, F., Ramezani, M. & Darroudi, M. Bio-sensing applications of cerium oxide nanoparticles: advantages and disadvantages. Biosens. Bioelectron. 96, 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2017.04.037 (2017).

Young, S. J., Liu, Y. H., Chu, Y. L. & Huang, J. Z. Nonenzymatic glucose sensors of ZnO nanorods modified by Au nanoparticles. IEEE Sens. J. 23, 12503–12510. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2023.3272778 (2023).

Mai, H. H. & Janssens, E. Au nanoparticle–decorated ZnO nanorods as fluorescent non-enzymatic glucose probe. Microchim. Acta. 187 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00604-020-04563-6 (2020).

De Luca, L. et al. Hydrogen sensing characteristics of Pt/TiO2/MWCNTs composites. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 37, 1842–1851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.10.017 (2012).

Haidry, A. A., Ebach-Stahl, A. & Saruhan, B. Effect of Pt/TiO2 interface on room temperature hydrogen sensing performance of memristor type Pt/TiO2/Pt structure. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 253, 1043–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2017.06.159 (2017).

Belal, M. A. et al. Advances in gas sensors using screen printing. J. Mater. Chem. A. 13, 5447–5497. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4TA06632D (2025).

Arshak, K., Gaidan, I. & Cavanagh, L. Screen-Printed Fe2O3 /ZnO thick films for gas sensing applications. Journal of Microelectronics and Electronic Packaging. 2 (1), 25-39 http://meridian.allenpress.com/jmep/article-pdf/2/1/25/2247169/1551-4897-2_1_25.pdf (2005).

Ahamed, A. et al. Environmental footprint of voltammetric sensors based on screen-printed electrodes: an assessment towards green sensor manufacturing. Chemosphere 278 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130462 (2021).

Llobet, E. et al. Screen-printed nanoparticle Tin oxide films for high-yield sensor microsystems. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 96, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-4005(03)00491-X (2003).

Hayat, A. & Marty, J. L. Disposable screen printed electrochemical sensors: tools for environmental monitoring. Sens. (Switzerland). 14, 10432–10453. https://doi.org/10.3390/s140610432 (2014).

Aliyana, A. K., Baburaj, A., Naveen Kumar, S. K. & Fernandez, R. E. Zinc Oxide-Based miniature sensor networks for continuous monitoring of aqueous pH in smart agriculture, in: Sensing Technologies for Real time Monitoring of Water Quality, Wiley, Ltd, : 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119775843.ch6. (2023).

Young, S. J. & Tang, W. L. Wireless zinc oxide based pH sensor system. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, B3047–B3050. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0071909jes (2019).

Sharma, P. et al. Development of ZnO nanostructure film for pH sensing application. Appl. Phys. Mater. Sci. Process. 126 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-020-03466-w (2020).

Panda, S. K. & Jacob, C. Preparation of transparent ZnO thin films and their application in UV sensor devices. Solid State Electron. 73, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sse.2012.03.004 (2012).

Xu, Q. et al. Flexible Self-Powered ZnO film UV sensor with a high response. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11, 26127–26133. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b09264 (2019).

Wang, J. & Chen, Y. Enhanced methane sensing properties of SnO2Nanoflowers with ag doping: A combined experimental and First-Principle study. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2021.3130053 (2022).

Moon, C. S., Kim, H. R., Auchterlonie, G., Drennan, J. & Lee, J. H. Highly sensitive and fast responding CO sensor using SnO2 nanosheets. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 131, 556–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2007.12.040 (2008).

Wang, B., Zhu, L. F., Yang, Y. H., Xu, N. S. & Yang, G. W. Fabrication of a SnO2 nanowire gas sensor and sensor performance for hydrogen. J. Phys. Chem. C. 112, 6643–6647. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp8003147 (2008).

Karunagaran, B., Uthirakumar, P., Chung, S. J., Velumani, S. & Suh, E. K. TiO2 thin film gas sensor for monitoring ammonia. Mater. Charact. 58, 680–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2006.11.007 (2007).

Xie, T. et al. UV-assisted room-temperature chemiresistive NO2 sensor based on TiO2 thin film. J. Alloys Compd. 653, 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.09.021 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Hollow-Out Fe2O3-Loaded NiO heterojunction nanorods enable Real-Time exhaled ethanol monitoring under high humidity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 15, 15707–15720. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c23088 (2023).

Liang, S. et al. Highly sensitive acetone gas sensor based on ultrafine α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 238, 923–927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2016.06.144 (2017).

Wang., X, Shi., J, Shen., W, Xu., P. and Li., X. A Non-Enzymatic Electrochemical Sensor Based on Cerium Oxide Nanocubes for the Rapid Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide Residues in Food Samples, 2023 22nd International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (Transducers), Kyoto, Japan, 2023, pp. 565-568. keywords: {Micromechanical devices;Transducers;Hydrogen;Cerium;Conductivity;Nanomaterials;Reproducibility of results;Cerium Oxide Nanocubes;Electrochemical Microsensor;Hydrogen Peroxide Detection;Catalytical Nanomaterial;Disposable Chip},

Bhuvaneshwari, S. & Gopalakrishnan, N. Hydrothermally synthesized copper oxide (CuO) superstructures for ammonia sensing. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 480, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2016.07.004 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Boron vacancies of mesoporous MnO2 with strong acid sites, free Mn3 + species and macropore decoration for efficiently decontaminating organic and heavy metal pollutants in black-odorous waterbodies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 561 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.150081 (2021).

Carbone, M. & Tagliatesta, P. NiO grained-flowers and nanoparticles for ethanol sensing. Materials 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/MA13081880 (2020).

Bohórquez Martínez, C., Vazquez Arce, J. L., Cuentas Gallegos, A. K. & Tiznado, H. Enhanced oxygen sensing in ZrO2 thin films via atomic layer deposition by post-deposition annealing. Ceram. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.12.380 (2025).

Fragal, M. E., Aleeva, Y. & Malandrino, G. ZnO Nanorod arrays fabrication via chemical bath deposition: ligand concentration effect study. Superlattices Microstruct. 48, 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spmi.2010.07.007 (2010).

Zainelabdin, A., Zaman, S., Amin, G., Nur, O. & Willander, M. Deposition of well-aligned ZnO nanorods at 50 °c on metal, semiconducting polymer, and copper oxides substrates and their structural and optical properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 10, 3250–3256. https://doi.org/10.1021/cg100390x (2010).

Zainelabdin, A., Zaman, S., Amin, G., Nur, O. & Willander, M. Stable white light electroluminescence from highly flexible Polymer/ZnO nanorods hybrid heterojunction grown at 50°C. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 5, 1442–1448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-010-9659-1 (2010).

Verma, G. et al. Multiplexed gas sensor: fabrication strategies, recent progress, and challenges. ACS Sens. 8, 3320–3337. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.3c01244 (2023).

Kim, D. et al. Inkjet-printed zinc Tin oxide thin-film transistor. Langmuir 25, 11149–11154. https://doi.org/10.1021/la901436p (2009).

Vernieuwe, K., Feys, J., Cuypers, D. & De Buysser, K. Ink-Jet printing of aqueous inks for Single-Layer deposition of Al-Doped ZnO thin films. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 99, 1353–1359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.14059 (2016).

Shen, W., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, C. The Preparation of ZnO based gas-sensing thin films by ink-jet printing method. Thin Solid Films. 483, 382–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2005.01.015 (2005).

Sahner, K. & Tuller, H. L. Novel deposition techniques for metal oxide: prospects for gas sensing. J. Electroceram. 24, 177–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10832-008-9554-7 (2010).

Kasi, V. et al. Low-Cost flexible Glass-Based pH sensor via cold atmospheric plasma deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 14, 9697–9710. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c19805 (2022).

Sonawane, A. et al. Communication—Detection of salivary cortisol using zinc oxide and copper porphyrin composite using electrodeposition and Plasma-Assisted deposition. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 9, 061022. https://doi.org/10.1149/2162-8777/aba856 (2020).

Verma, G., Singhal, S., Rai, P. K. & Gupta, A. A simple approach to develop a paper-based biosensor for real-time uric acid detection. Anal. Methods. 15, 2955–2963. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3AY00613A (2023).

Verma, G., Gokarna, A., Kadiri, H., Lerondel, G. & Gupta, A. Flexible ZnO nanowire platform by metal-seeded chemical bath deposition: parametric analysis and predictive modeling. Appl. Mater. Today. 40, 102385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmt.2024.102385 (2024).

Jalajamony, H. M., Nair, M., Doshi, P. H., Gandhiraman, R. P. & Fernandez, R. E. Plasma Printed Antenna for Flexible Battery-Less Smart Mask for Lung Health Monitoring. In: FLEPS 2023 - IEEE International Conference on Flexible and Printable Sensors and Systems, Proceedings, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/FLEPS57599.2023.10220224

Nordlund, D., Doshi, P., Gutierrez, D. & Gandhiraman, R. Plasma Jet Printing for Printed Electronics, In: IFETC 2023–5th IEEE International Flexible Electronics Technology Conference, Proceedings, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., https://doi.org/10.1109/IFETC57334.2023.10254802 (2023).

Gandhiraman, R. P., Beeler, D., Meyyappan, M. & Khare, B. N. Low temperature atmospheric pressure plasma sterilization shower. LPI Contributions. 1058 (2012).

Dey, A. et al. Plasma jet printing and in situ reduction of highly acidic graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 12, 5473–5481. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b00903 (2018).

Gutierrez, D., Doshi, P., Wong, H. Y., Nordlund, D. & Gandhiraman, R. P. Printed graphene and its composite with copper for electromagnetic interference shielding applications. Nanotechnology 35 https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/ad12e9 (2024).

Jalajamony, H. M. et al. Plasma-aided direct printing of silver nanoparticle conductive structures on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) surfaces. Sci. Rep. 14 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82439-y (2024).

Aliyana, A. K. et al. Plasma jet printed AgNP electrodes for high-performance fabric TENGs and adaptive sensing applications. Chem. Eng. J. 504, 158791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.158791 (2025).

Manzi, J., Kandadai, N., Gandhiraman, R. P. & Subbaraman, H. Plasma jet printing: an introduction. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 70, 1548–1553. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2023.3248526 (2023).

Gandhiraman, R. P., Nordlund, D., Jayan, V., Meyyappan, M. & Koehne, J. E. Scalable low-cost fabrication of disposable paper sensors for DNA detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 22751–22760. https://doi.org/10.1021/am5069003 (2014).

Daniel, P. D. D. N., Gutierrez Ranajoy, H., Bhattacharya, R. P. & Gandhiraman Plasma jet printing of copper and silver antennas operating at 2.4 ghz. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 38, 790–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/09205071.2024.2336033 (2024).

Rong, P., Ren, S. & Yu, Q. Fabrications and applications of ZnO nanomaterials in flexible functional Devices-A review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 49, 336–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2018.1531691 (2019).

Manjakkal, L., Szwagierczak, D. & Dahiya, R. Metal oxides based electrochemical pH sensors: current progress and future perspectives. Prog Mater. Sci. 109 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.100635 (2020).

Alizadeh, N., Salimi, A., Sham, T. K., Bazylewski, P. & Fanchini, G. Intrinsic Enzyme-like activities of cerium oxide nanocomposite and its application for extracellular H2O2Detection using an electrochemical microfluidic device. ACS Omega. 5, 11883–11894. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b03252 (2020).

Uzunoglu, A. & Ipekci, H. H. The use of CeO2-modified Pt/C catalyst inks for the construction of high-performance enzyme-free H2O2 sensors. J. Electroanal. Chem. 848 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2019.113302 (2019).

Shcherbakov, A. B. et al. Ceo2 nanoparticle-containing polymers for biomedical applications: A review. Polym. (Basel). 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13060924 (2021).

Saha, P., Maharajan, A., Dikshit, P. K. & Kim, B. S. Rapid and reusable detection of hydrogen peroxide using polyurethane scaffold incorporated with cerium oxide nanoparticles. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 36, 2143–2152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-019-0399-3 (2019).

Young, S. J., Lai, L. T. & Tang, W. L. Improving the performance of pH sensors with One-Dimensional ZnO nanostructures. IEEE Sens. J. 19, 10972–10976. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2019.2932627 (2019).

Fulati, A. et al. Miniaturized pH sensors based on zinc oxide nanotubes/nanorods. Sensors 9, 8911–8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/s91108911 (2009).

Zhang, Q. et al. On-chip surface modified nanostructured ZnO as functional pH sensors. Nanotechnology 26 https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/26/35/355202 (2015).

Zhao, Y., Lei, M., Liu, S. X. & Zhao, Q. Smart hydrogel-based optical fiber SPR sensor for pH measurements. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 261, 226–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2018.01.120 (2018).

Jha, S. K., Kumar, C. N., Raj, R. P., Jha, N. S. & Mohan, S. Synthesis of 3D porous CeO2/reduced graphene oxide xerogel composite and low level detection of H2O2. Electrochim. Acta. 120, 308–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2013.12.051 (2014).

Kosto, Y. et al. Electrochemical activity of the polycrystalline cerium oxide films for hydrogen peroxide detection. Appl. Surf. Sci. 488, 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.05.205 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Mn3O4-CeO2 Hollow nanospheres for electrochemical determination of hydrogen peroxide. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 2116–2124. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.2c05123 (2023).

Guan, H., Zhang, J., Liu, Y., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, B. Rapid quantitative determination of hydrogen peroxide using an electrochemical sensor based on PtNi alloy/CeO2 plates embedded in N-doped carbon nanofibers. Electrochim. Acta. 295, 997–1005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2018.11.126 (2019).

Luo, Y. et al. Tailored fabrication of Defect-Rich ion implanted ceo 2-x nanoflakes for electrochemical sensing of H 2 O 2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 170, 057519. https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/acd41f (2023).

Acknowledgements

Support from National Science Foundation grants #2100930, #1827847 (PREM Grant), and #2112595 (CREST) are acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.E.F. and G.R. designed the experiments, supervised the project, and co-wrote the manuscript. N.K.G. conducted the electrochemical experiments for CeO2 and co-wrote the manuscript. H.M.J. fabricated the metal oxide nanostructure samples and co-wrote the manuscript. S.A. performed the electrochemical analysis of ZnO and carried out the UV-Vis spectroscopy. S.D. acquired and analyzed the SEM images. R.A. and S.S. assisted in the experimental work. All authors participated in completing the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gunasekaran, N.K., Jalajamony, H.M., Adhinarayanan, S. et al. Direct printing of metal oxide nanostructures for wearable electrochemical sensing. Sci Rep 15, 22380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04426-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04426-1