Abstract

Developing efficient green corrosion inhibitors from sustainable, renewable, and cost-effective materials is a pressing challenge. Solvents impact carbon dot structures, leading to property disparities, yet the mechanism of solvent-induced structure–property modulation in carbon dots remains not deeply understood. Herein, dried dandelion leaves served as carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur sources. Using 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide (an ionic liquid, IL) and water as solvents, nitrogen- and sulfur-functionalized biomass-derived CDs, namely IL-CDs and CDs, were synthesized. The inhibition performance of IL-CDs and CDs for carbon steel in H2SO4 solution was evaluated by electrochemical measurements and surface characterizations. Both IL-CDs and CDs contained abundant N- and S-functional groups, endowing them with photoluminescence and distinct UV–Vis spectral features. The IL increased the content of pyrrole-like nitrogen and C-SOx group, facilitating the formation of a denser protective film. IL-CDs (~ 38.3 nm) showed better inhibition efficiency (75.9%) than CDs (73.1%). Adsorption isotherms and corrosion morphology analyses indicated that the inhibition mechanism of IL-CDs and CDs mainly involved physical and chemical adsorption to form a protective film. Notably, pyrrole-like nitrogen species, through π-complex formation, enabled parallel adsorption onto the steel surface, playing a key role in inhibition. This study presents a green strategy for synthesizing efficient biomass-derived carbon dots with IL assistance, advancing the development of sustainable and effective inhibitors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reducing global steel demand through improved corrosion resistance to mitigate carbon emissions is a critical challenge1. Carbon steel is commonly used in industries, such as construction, petrochemicals, and boilers, due to its stable physical and chemical properties, as well as its low cost. However, it is susceptible to corrosion when exposed to acidic media during processes like acid pickling and oil well acidizing. Therefore, the development of efficient, cost-effective, and easily applicable corrosion inhibitors is crucial for protecting carbon steel from corrosive environments.

Organic compounds with O, N, S, and P heteroatoms, heterocycles, or conjugated unsaturated bonds, are commonly used as inhibitors in acidic environments2,3,4,5. Their inhibition mechanism typically involves the formation of protective films onto the metal surfaces via physical and/or chemical interactions, thereby slowing corrosion6. However, traditional organic inhibitors often cause environmental pollution, prompting interest in “green” alternatives, such as amino acids, ionic liquids (IL/ILs), and plant extracts7. Despite their promise, these green inhibitors possess certain inherent limitations. For example, plant extracts often require complex procedures and toxic solvents, which adversely impact the environment8,9, while some ILs and amino acids are costly and unsuitable for large-scale use. Consequently, there is growing interest in sustainable, efficient inhibitors with simple synthesis processes.

Carbon dots (CDs), a novel class of zero-dimensional carbon-based fluorescent nanomaterial discovered in 200410, have garnered attention as promising, eco-friendly, and sustainable inhibitors due to their low cost, abundant precursors, and tunable surface properties11,12. To enhance their inhibition performance, surface modifications, including heteroatom doping (e.g., N, S, Cu, Ce), are commonly employed during preparation or post-processing13,14,15. The aromatic ring structures with sp2-conjugated domains in CDs, along with surface functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and amino groups at their edges, serve as potential adsorption sites on metal surfaces, providing corrosion protection for metals like Fe, Cu, etc.16.

For instance, Ye et al. observed that pyridinic N and pyrrolic N in CDs facilitate chemical adsorption, while graphitic N aggregates on the metal surface to form a protective barrier through physical adsorption17. Bhargava et al. reported that polar N groups act as adsorption sites for metal interaction, whereas nonpolar R groups function as hydrophobic shields, providing physical protection18. Biomass resources, including plants and their by-products, are rich in organic components and offer significant advantages in preparing biomass-derived CDs, such as low cost, eco-friendliness, and accessibility. Biomass materials containing heteroatoms (N and S) are particularly valuable as precursors for CDs, yielding materials with lower biotoxicity compared to CDs derived from man-made carbon sources that require external heteroatom addition19.

Ionic liquids (ILs), versatile organic solvents with excellent solubility, stability, and tunable structures, influencing the physical and chemical properties of CDs, including the size, morphology, hydrophobicity, and surface functional groups20,21. ILs reduce interfacial tension and energy, promoting rapid nucleation of CDs and minimizing particle aggregation22. Wang et al. synthesized N, S-doped CDs (IL-CDs) using L-cysteine and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide as a solvent via a solvothermal method, achieving an inhibition efficiency of up to 97% for carbon steel in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution12.

CDs can be synthesized from a wide variety of precursors, such as graphite, small molecules (e.g., citric acid, urea), polymers, and natural materials (e.g., stems, leaves, roots, petals, and fruits)7,23. Using eco-friendly, readily available raw materials to produce high-performance CDs is essential for sustainable development. Biomass, being eco-friendly, abundant, low-cost, and renewable, represents an excellent carbon source for the synthesis of biomass-derived CDs23. Numerous studies have successfully synthesized biomass-derived CDs from plants24,25, applying them in diverse fields, such as plant systems26 and optoelectronics27. However, their application in corrosion protection remains underexplored7,28. Long et al. reported that CDs derived from lychee leaves, rich in O and N functional groups, achieved over 90% inhibition efficiency for carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution7. This highlights the significant potential of natural biomass-derived CDs as green inhibitors with high efficacy.

Therefore, developing simple synthesis methods for biomass-derived CDs and study their inhibition performance is of utmost importance. IL enables both physical and chemical modifications of carbon dots, effectively mitigating their inherent limitations, such as aggregation at high concentrations and suboptimal long-term corrosion inhibition performance due to weak intermolecular interactions12,29,30. Notably, the impacts of ILs and water (H2O) on the weak interactions between CDs and between CDs and metal surfaces are still not well-understood. In this study, biomass-derived CDs were synthesized from dandelion leaves, a traditional Chinese medicine, using facile, one-step solvothermal and hydrothermal methods. The influence of solvents on the inhibition performance of these CDs was comprehensively analyzed. The synthesized CDs were characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), UV–vis spectroscopy (UV–vis), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Their inhibition performance was evaluated through electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and Tafel polarization measurements. The results indicated that dandelion leaf-derived CDs, rich in oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur functional groups, exhibited notable inhibition in H2SO4 solution. Surface analysis techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), XPS, atomic force microscopy (AFM), and adsorption isotherms, provided the insights to the corrosion inhibition mechanism. This work demonstrates the effectiveness of biomass-derived CDs, especially those enhanced by IL, and underscores the role of IL in improving the dispersion and performance of CDs. These findings contribute to the development of eco-friendly, effective corrosion protection strategies.

Experimental

Materials and chemicals

Carbon steel samples (10 × 10 × 2 mm) used in this study were sourced from a local supplier, and their elemental composition (by weight) consists of C 0.16–0.20%, Mn 0.31–0.46%, Si 0.05–0.20%, S 0.008–0.022%, P 0.020–0.035%, with Fe constituting the balance. Prior to each experiment, the samples were grounded with waterproof sandpaper ranging from 400 to 2000 grit, washed with deionized water, degreased with isopropanol, and air-dried. Dandelion leaves, sourced from a village in Hebei province, China, were cleaned, dried, and ground for use.

Synthesis of IL-CDs and CDs

In contrast to conventional synthetic routes relying on precursors, such as citric acid and ammonium citrate, etc.31,32, the carbon dots in this study were synthesized from herbal-derived biomass (a widely available medicinal plant), offering advantages in environmental sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and material accessibility, compared to previously reported CD-based inhibitors, as demonstrated in prior studies33,34.

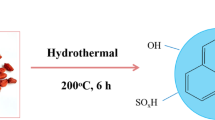

Natural dandelion leaves were selected as precursor for synthesizing carbon dots via hydrothermal/solvothermal methods using water and IL as solvents, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In a typical synthesis process, 2 g of dried dandelion powder was dissolved in 3 g of IL or 20 mL of water, and the mixture was thoroughly stirred before being placed in a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave. The mixture was then heated at 200 °C for 6 h. After natural cooling to room temperature, the resulting brown-black mixture was dissolved in 40 mL of deionized water and the solution was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was subsequently filtered and dialyzed in distilled water for 24 h using a dialysis membrane with a molecular weight cutoff of 1000 g/mol. After dialysis, the obtained mixture was vacuum-dried at 60 °C, yielding dark brown solid carbon dots, named IL-CDs and CDs based on the IL and water solvents used, respectively, with a yield of approximately 3–5%.

Preparation of IL-CDs and CDs solution

To investigate the inhibition behavior of IL-CDs and CDs in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, the concentrations of IL-CDs were selected as 15, 75, 100, and 150 mg/L, while 150 mg/L CDs was prepared for comparison. The 0.5 M H2SO4 solution was ordered from Guangzhou Howei Pharma Technology Co., Ltd.

Structure characterization of IL-CDs and CDs

The morphology of IL-CDs and CDs was examined using transmission electron microscope (TEM, Tecnai G2 Spirit, USA). Both IL-CDs and CDs were dispersed in ethanol, dropped onto a copper mesh, dried, and subsequently analyzed by TEM. The chemical composition and structural information were obtained using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50, USA) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, PHI 5000 VersaProbe III, Japan). XPS measurements were collected using an Al Kα anode (1486.6 eV), with the binding energy reference set at the C 1s peak of carbon, 284.8 eV. Ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectra of IL-CDs and CDs in deionized water were recorded using quartz cells (1 cm path length) in the 200–800 nm range with a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Agilent Cary 5000, USA).

Electrochemical measurement

Electrochemical tests, including electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) and Tafel polarization (PO), were conducted using a three-electrode system with an electrochemical workstation (CHI604D). A carbon steel electrode (1 cm2 exposed area) was used as the working electrode, while a platinum (Pt) sheet and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) served as the counter electrode and the reference electrode, respectively. The working electrode was immersed in a 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, either with or without the inhibitor, for 3600 s. Open circuit potential (OCP) measurements were conducted at 298.15 K until a stable OCP was reached, followed by EIS and PO.

EIS measurements were performed with an AC signal amplitude of 5 mV over a frequency range of 105 to 0.01 Hz. Tafel polarization curves were recorded over a potential range of ± 0.25 V versus OCP at a scan rate of 0.5 mV/s. All experiments were repeated three times to ensure reproducibility. EIS data were fitted and analyzed using ZSimDemo software. The inhibition efficiency derived from EIS was calculated using Eq. 135.

where R0ct and Rct are the charge transfer resistances of carbon steel without and with the inhibitor, respectively, in Ω/cm2. IEEIS% refers to the inhibition efficiency gained from EIS tests.

The inhibition efficiency from PO was calculated using Eq. 235.

where i0corr and icorr represent the corrosion current densities of carbon steel in the absence and presence of the inhibitor, respectively, measured in A/cm2. IEtafel% refers to the inhibition efficiency gained from PO tests.

Surface characterization

For surface characterization, carbon steel samples (1 × 1 × 0.2 cm) were immersed in 0.5 M H2SO4 solutions in the absence and presence of 150 mg/L of IL-CDs or CDs for 6 h. After immersion, the samples were removed from solution, cleaned with acetone, and air-dried. Surface morphology and elemental distribution after inhibitor adsorption were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, (KYKY-EM8000) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (Oxford Instruments). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, PHI 5000 VersaProbe III, Japan) was used to analyze the chemical states on the steel surface. Atomic force microscopy (AFM, Bruker Dimension iCon, Germany) was employed to observe the morphology and roughness of the corroded steel.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of IL-CDs and CDs

Figure 2 shows the TEM images and particle size distributions of the synthesized IL-CDs and CDs. The average size of IL-CDs is approximately 38.3 nm (Fig. 2a1,a2), while that of CDs is around 17.5 nm (Fig. 2b1,b2). Both types of carbon dots are highly dispersed and exhibit nearly quasi-spherical morphologies. The use of IL as a solvent plays a crucial role in yielding larger and more uniformly distributed carbon dots. This is because ILs do not engage in the formation of carbon nuclei during the synthesis of IL-CDs. Notably, compared to CDs, IL-CDs exhibit larger and more uniform particle sizes. The increased particle size is likely due to the IL’s role in facilitating polycondensation reactions, thus promoting the growth of more homogeneous structures. TEM analysis further confirms that the carbohydrates from dandelion leaves undergo dehydration, condensation, polymerization, and subsequent carbonization under heat and pressure. This process leads to the formation of IL-CDs and CDs with sp2 carbon structures at their cores.

FTIR analysis revealed the surface chemical states of the as-prepared IL-CDs and CDs. The FTIR spectra (Fig. 3a) show characteristic peaks at 3273, 1648, and 1382 cm−1 for IL-CDs, and at 3262, 1634, and 1401 cm−1 for CDs. This peaks confirmed the presence of O–H/N–H, C=O, and C–N bonds, respectively36,37. The abundant oxygen-, nitrogen-, and sulfur-containing functional groups endow IL-CDs and CDs with outstanding water solubility and dispersibility, making them ideal candidates as water-based inhibitors. Additionally, the peaks at 2931 cm−1 for IL-CDs and 2934 cm−1 for CDs are attributed to C–H stretching vibrations, while the peaks at 1596 cm−1 for IL-CDs and 1578 cm−1 for CDs correspond to C–C stretching vibrations in aromatic rings38. This confirmed the sp2 carbon structure, which is consistent with the TEM results.

The UV–visible absorption spectra (Fig. 3b) display a broad peak between 250 and 350 nm for the dandelion precursor. After the transformation into carbon dots, two weak absorption peaks appear at approximately 275 nm and 320 nm. These peaks correspond to the π–π* transition of aromatic sp2 carbon and the n-π* transition of oxygen-, nitrogen-, and sulfur-containing functional groups, respectively39. As depicted in the inset of Fig. 3b, the aqueous solutions of IL-CDs and CDs appear light yellow under visible light and emit strong blue photoluminescence (PL) when excited at 365 nm UV light. The UV–visible absorption spectra confirm the successful synthesis of the carbon dots.

The XPS survey spectrum (Fig. 4a) shows four characteristic peaks corresponding for C, O, S, and N. The high-resolution C 1s spectrum (Fig. 4b) is deconvoluted into four distinct peaks at 284.8, 285.5 ± 1, 286.5, and 288.2 eV. These peaks can be assigned to C–C/C=C, C–N/C-S, C–O, and C=N/C=O bonds, respectively, thereby confirming the successful doping of N and S into the CDs40. The N 1s spectrum (Fig. 4c) is deconvoluted into three peaks at 398.2 eV, 399.5 eV, and 401.3 eV, which correspond to pyridinic nitrogen, pyrrolic nitrogen, and graphitic nitrogen, respectively41,42. Among them, pyrrolic nitrogen is predominant, and only minor pyridinic nitrogen is detected. The O 1s spectrum in Fig. 4d shows peaks at 531.0 eV and 531.8 eV, which are attributed to C=O and C–O bonds, respectively43. In Fig. 4e, the S 2p spectrum displays two peaks at 163.9 and 167.7 ± 1 eV, which are attributed to the C-S bond and C-SOx groups, respectively44. Sulfur predominantly exists in the form of C-SOx within the carbon dots. These findings indicate the sulfur is mainly derived from glucosinolates in the dandelion leaves. These results confirm the successful synthesis of N- and S- co-doped IL-CDs and CDs.

Table 1 shows a detailed summary of the nitrogen species in both IL-CDs and CDs. Pyridinic nitrogen donates lone-pair electrons to form Fe–N bonds perpendicular to the steel surface45. In contrast, pyrrolic nitrogen interacts with the steel surface via its aromatic ring, forming a π-complex that aligns the pyrrole ring parallel to the surface46. Thus, the adsorption of pyrrolic nitrogen significantly contributes to corrosion inhibition. As indicated in Table 1, IL-CDs, having a higher content of pyrrolic nitrogen, demonstrate superior inhibition performance.

The XPS measurements corroborate the conclusions drawn from the FTIR spectra. They strongly supporting the fact that IL-CDs and CDs are composed of an sp2 carbon core with a passivated surface rich in oxygen-, nitrogen- and sulfur-containing functional groups, which play a key role in their corrosion inhibition properties.

Electrochemical analysis

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis

The Nyquist and corresponding Bode plots of carbon steel immersed in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution in the absence and presence of IL-CDs, are displayed in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. The Nyquist plots (Fig. 5) show depressed capacitive loops, indicative of the charge transfer process occurring at the electrode/solution interface at high frequencies, both in the uninhibited and inhibited with IL-CDs and CDs. The diameter of the capacitive loop increases after the addition of IL-CDs and CDs. Moreover, the depression of the semicircle, with its center located below the x-axis, is associated with the inhomogeneity and roughness of the steel surface47,48. At low frequencies, a small inductive loop appears, which is attributed to relaxation processes, such as the adsorption of H⁺ and SO42− ions onto the steel surface49,50.

The Bode plots in Fig. 6 reveal that all phase angles predominantly exhibit a single phase peak, and as the IL-CDs concentration increases, the maximum phase angle shifts towards higher values (Fig. 6a). Additionally, the impedance modulus (Fig. 6b) increases with the addition of IL-CDs, implying that IL-CDs enhance the protective capability of the steel. These results indicate that the addition of IL-CDs endows the steel with effective protective.

Based on these results, a simple-constant equivalent circuit and a two-time-constant equivalent circuit were respectively used to analyze the EIS data in the absence and presence of IL-CDs (Fig. 7). These circuits consist of solution resistance (Rs), charge transfer resistance (Rct), a constant-phase angle element (CPE/Q) to replace ideal double-layer capacitance due to the non-ideal capacitance behavior of the inhomogeneous electrode47, inductance (L), and inductive resistance (RL).

The inductance (L) is related to the relaxation process caused by adsorbed species (such as H⁺ and SO42−) on the steel surface. The impedance of CPE is described as follows51:

where Y0 is the modulus of the CPE, n (− 1 ≤ n ≤ 1) is the CPE exponent, j (j = (− 1)1/2) refers to an imaginary number, and ω (ω = 2πf) is the angular frequency in rad−1.

Cdl can be obtained by the following equation51:

where fmax refers to the maximum frequency of the impedance spectrum.

ωmax can also be calculated by the following equation51:

where d refers to the thickness of the double layer, ε0 is a constant of the permittivity of air, ε is the local dielectric constant, and S represents the area of the surface of working electrode.

The electrochemical parameters derived from EIS data by using these circuits are summarized in Table 2. The results show that upon the addition of IL-CDs, the Rct values increase while the Cdl values decrease, and these effects are more pronounced at higher IL-CDs concentrations. This indicates a decrease in the local dielectric constant ε and/or an increase in the doouble-layer thickness d, likely attributed to the formation of an adsorption film at the metal/solution interface. Is is inferred that IL-CDs molecules interact with the steel surface through adsorption, simultaneously with the displacement of H2O molecules or other ions that were originally adsorbed on the steel surface from the bulk solution. This process effectively reduces the corrosion rate. At 298 K, it reaches a maximum of 77.2% at 150 mg/L, in contrast to 17.2% at 15 mg/L.

To compare the impact of different solvents on the performance of inhibitors, the inhibition behavior of IL-CDs and CDs for carbon steel in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution is further analyzed. The Nyquist and relevant Bode plots are displayed in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively. The Nyquist plots (Fig. 8) show depressed capacitive loops. These loops, corresponding to the charge-transfer process at electrode/solution interface at the high frequencies, are present in both the blank and those with IL-CDs and CDs. The addition of IL-CDs and CDs increases the diameter of the capacitive loop. The depressed semicircle with its center below the x-axis further indicates the inhomogeneity and roughness of the steel surface52. At low frequencies, a small inductive loop appears owing to relaxation processes such as H+ads and SO42−ads on the metal substrates53,54.

The Bode plot in Fig. 9 shows that the addition of IL-CDs and CDs increases the impedance modulus and shifts the frequency at the maximum phase angle to higher values in inhibited solutions. To analyze the EIS data, the two-time-constant equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 7 was used, and the corresponding electrochemical parameters are summarized in Table 3. It is evident that with the addition of IL-CDs and CDs, Rct values increase while Cdl values decrease, indicating the formation of a protective film at the metal/solution interface. Notably, IL-CDs shows a higher value of Rct than CDs, resulting in a higher inhibition efficiency of 77.2% for IL-CDs compared to 76.6% for CDs.

Polarization (PO) analysis

Figure 10 shows the PO plots of carbon steel in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution,either uninhibited or inhibited with varying concentrations of IL-CDs. Table 4 shows the corresponding electrochemical parameters, such as corrosion current density (icorr), corrosion potentials (Ecorr), inhibition efficiency (IE%), anodic slope (βa), and cathodic slope (βc). As illustrated in Fig. 10, compared to the blank solution, both the cathodic and anodic branches of the Tafel plots shift towards lower current densities, and this trend becomes more pronounced as the concentration of IL-CDs increases.

From Table 4, it is evident that, in the presence of IL-CDs, all icorr values, including cathodic and anodic current densities are lower than those of the blank. This indicates that both the cathodic dissolution of Fe and the anodic hydrogen evolution reactions are inhibited. Furthermore, the corrosion current densities decrease as the IL-CDs concentration rises. The maximum shift of Ecorr in the presence of IL-CDs is less than ± 85 mV, indicating that IL-CDs act as a mixed-type inhibitor, retarding both anodic and cathodic reaction55. Correspondingly, the Ecorr and IE% values increase with the IL-CDs concentration, with a maximum IE% reaching 75.9%.

Figure 11 shows the polarization plots of carbon steel immersed in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution uninhibited and inhibited with 150 mg/L IL-CDs and CDs. The corresponding electrochemical parameters are presented in Table 5. The Tafel plots reveal that, compared to the uninhibited steel, both the cathodic and anodic branches of IL-CDs and CDs shift towards lower current densities. Notably, IL-CDs exhibit slightly lower current densities and more positive Ecorr values than CDs. This shift indicates that both IL-CDs and CDs act as mixed-type inhibitors, with a predominantly cathodic inhibition effect.

As shown in Table 5, at a constant concentration, IL-CDs exhibit slightly lower icorr, more positive Ecorr and higher IE% values than CDs. This observation correlates with the higher proportion of pyrrolic N in IL-CDs, indicating that the pyrrolic N content is a crucial factor influencing the inhibition efficiency. Pyridine nitrogen typically donates lone pair electrons to form a direct Fe–N bond perpendicular to the steel surface46, while pyrrole nitrogen interacts with the steel surface via its aromatic ring, forming a π-complex that aligns the pyrrole ring parallel to the surface46. Therefore, the pyrrole group contributes more significantly to corrosion inhibition. As indicated in Table 1, IL-CDs have a higher concentration of pyrrolic nitrogen, which likely accounts for their superior inhibition performance. The inhibition performance is in good agreement with the results obtained from the EIS results.

Corrosion morphology analysis

SEM

Figure 12 shows the SEM images of carbon steel before and after 6 h immersion in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, in the absence and presence of 150 mg/L IL-CDs and CDs. The steel surface before immersion is relatively smooth, with some polishing-induced scratches (Fig. 12a). However, after immersion in the inhibitor-free H2SO4 solution, the steel surface is severely corroded, featuring a rough structure and numerous corrosion products (Fig. 12b). In contrast, the steel surfaces treated with IL-CDs and CDs exhibit less corrosion damage, with IL-CDs-treated surface showing the least deterioration, indicating that IL-CDs provide superior inhibition compared to CDs (Fig. 12c,d).

EDS analysis of the steel without IL-CDs detected C, O, Fe and S elements (Fig. 12e). Notably, the N element was detected on the carbon steel treated with IL-CDs, indicating the successful adsorption of IL-CD molecules onto the steel surface (Fig. 12f). Additionally, compared to the blank, the intensity of S and O on the steel surface decreases in the presence of IL-CDs, further validating its inhibition ability. Elemental scanning images in Fig. 13 show a significant distribution of O on the steel surface, indicating an oxidation reaction. Meanwhile, the N element is evenly distributed on the IL-CDs treated steel surface, illustrating a uniform distribution of IL-CDs (Fig. 13). This distribution implies that the protective film formed by IL-CDs effectively suppresses steel corrosion.

Compared to the blank H2SO4 solution, in the presence of 150 mg/L IL-CDs, the Fe element content on the steel surface increases from 50.4 to 60.4 at%, accompanied by a decrease in the O element content from 22.1 to 7.9 at%. This evidence supports the fact the homogenous protective film formed by IL-CDs adsorption restricts corrosion caused by the blank H2SO4 solution, resulting in fewer corrosion products on the steel surface.

XPS

XPS data further validate the EDS analysis findings. As seen in Fig. 14a, XPS full spectra show C, O, Fe, and S atoms on the steel surface in both uninhibited and inhibited solutions with 150 mg/L IL-CDs and CDs. Nitrogen from the IL-CDs and CDs is detected in the inhibited solution, indicating their successful adsorption onto the steel surface to form a protective film. Figure 14b shows three peaks in the high-resolution N 1s spectrum: C–N (398.7 eV), Fe–N (400.0 eV), and N+H (401.2 eV)56. This suggests that IL-CDs and CDs interact with the steel surface via both chemical (C–N and Fe–N) interactions and physical (N+H) interactions, forming a homogenous protective layer that effectively mitigates corrosion in the aggressive H2SO4 solution.

In Fig. 14c, sulfur (S) appears as Fe-S (168.3 eV) and SO42− (169.3 eV)57. The O 1s spectrum in Fig. 14d shows three peaks at 529.6, 531.7 ± 1, and 532.8 eV, attributed to O2−, –OH of hydrous iron oxides (e.g., FeOOH)41, and O–C=O, respectively42.

These results imply that IL-CDs adsorb onto the steel surface through chemical adsorption, complexing with Fe using lone pair electrons from N and S. Meanwhile, protonated nitrogen (N+H) interacts physically with the steel surface through electrostatic forces.

AFM analysis

The AFM images of steel surfaces, immersed in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution with and without 150 mg/L IL-CDs and CDs for 6 h at 298 K, are illustrated in Fig. 15. After immersion in the acidic solution (Fig. 15a), the steel surface exhibits obvious depression and a high average roughness (Ra = 153 nm). In contrast, the steel surfaces treated with IL-CDs and CDs (Fig. 15b,c) appear noticeably smoother, with average roughness values of 34.3, and 35.6 nm, respectively. These results demonstrate that both IL-CDs and CDs effectively mitigate steel corrosion, which is consistent with the electrochemical and SEM results.

Adsorption type analysis

In acidic media, the inhibition mechanisms of organic inhibitors are generally regards as physical adsorption, chemisorption, or a combination of both, often accompanied by the displacement of water molecules from the metal surface. The Langmuir adsorption isotherm is commonly utilized to analyze the adsorption type, which is as follows58:

where Cinh is the inhibitor concentration, Kads is the equilibrium constant, and θ (defined as θ = IE%/100) represents the surface coverage by the inhibitor molecules.

The relationship between Cinh and Cinh/θ is displayed in Fig. 16. The slope of the Langmuir adsorption isotherm for IL-CDs is close to 1, with a linear correlation coefficient (R2) exceeding 0.93. The standard free energy (ΔG0ads) is obtained using the following equation58:

where CH2O is 1000 g/L, R is the gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), and T is the temperature in Kelvin.

Kads value provides insight into the adsorption strength of an inhibitor. A higher Kads value implies stronger adsorption on the metal surface59. If ΔG°ads is negative, the adsorption process is spontaneous, vice versa. The ΔG°ads values for IL-CDs, derived from EIS and PO results, are − 24.8 and − 23.9 kJ mol−1, respectively, indicating that the adsorption is spontaneous and occurs at the steel/solution interface. Although the magnitude of ΔG°ads alone may not definitively distinguish between physisorption and chemisorption28,60, it is generally accepted that if ΔG0ads > − 20 kJ mol−1, the process is classified as physical adsorption, whereas values less than − 40 kJ mol−1 indicate chemical adsorption, Values between − 40 and − 20 kJ mol−1 suggests a mixed mechanism of physisorption and chemisorption58. Based on these criteria, the adsorption of IL-CDs onto the steel surface is classified as physicochemical process at the steel/solution interface. The analysis of SEM/EDS and XPS supports the presence of both physical and chemisorption mechanisms.

Inhibition mechanism

The inhibition mechanism of the as-prepared IL-CDs and CDs in H2SO4 solution involves both physical and chemical adsorption of inhibitor molecules onto the steel surface (Fig. 17). On one hand, through electrostatic interactions, protonated IL-CDs and CDs physically adsorb onto the charged steel surface. On the other hand, pyridine-like N, pyrrole-like N, O, and S atoms in IL-CDs and CDs undergo chemical adsorption. Specifically, pyridine-N and pyrrole-like N coordinate with the unfilled 3d orbitals of Fe atoms on the steel surface, facilitating the formation of a protective layer that enhances corrosion resistance. In addition, the graphitic N atoms in IL-CDs and CDs contribute to protective shielding through electrostatic interactions. The O and S atoms, with their lone electron pairs, further enhance the adsorption, providing additional protection against the aggressive attacks of acid , Consequently, IL-CDs exhibit superior corrosion inhibition performance, attributed to their higher concentration of pyrrolic N compared to CDs.

Conclusion

In this study, two types of biomass-derived N- and S- co-doped functionalized carbon dots (IL-CDs and CDs) were facilely synthesized using dried dandelion as the precursor, with IL and H2O employed as solvents, respectively. These carbon dots were comprehensively characterized, and their inhibition performance on carbon steel in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution was systematically investigated. The mechanism of solvent-induced structure–property modulation in carbon dots is proposed. The main findings are summarized as follows:

-

1.

Electrochemical results reveal that biomass-derived IL-CDs and CDs exhibit effective inhibition efficiency. IL-CDs provide better inhibition efficiency than CDs, which is closely associated with the higher concentration of pyrrolic-like N and the increased surface density of the C-SOx functional group in IL-CDs. The O and S atoms, with their lone electron pairs, facilitate adsorbing onto the steel surface, providing enhanced corrosion protection.

-

2.

Surface morphological observations are consistent with electrochemical results, demonstrating that the pyrrolic-like, protonated N and sulfonate C-SOx group in IL-CDs and CDs promote adsorption onto the steel surface, forming a protective barrier against the corrosive attack of aggressive ions present in the solution.

-

3.

The ΔGads value indicates that the adsorption of IL-CDs onto the steel surface occurs spontaneously and follows the Langmuir adsorption isotherm model.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Iannuzzi, M. & Frankel, G. S. The carbon footprint of steel corrosion. npj Mater. Degrad. 6, 101–103 (2022).

Li, W., He, Q., Pei, C. & Hou, B. Experimental and theoretical investigation of the adsorption behaviour of new triazole derivatives as inhibitors for mild steel corrosion in acid media. Electrochim. Acta 52, 6386–6394 (2007).

Zhang, Q. H. et al. Two amino acid derivatives as high efficient green inhibitors for the corrosion of carbon steel in CO2-saturated formation water. Corros. Sci. 189, 109596–109709 (2021).

Zhu, Y. Q. et al. Molecular dynamic simulation and experimental investigation on the synergistic mechanism and synergistic effect of oleic acid imidazoline and L-cysteine corrosion inhibitors. Corros. Sci. 185, 109414–109424 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Inhibition effect of sparteine isomers with different stereochemical conformations on the corrosion of mild steel in hydrochloric acid solution. J. Mol. Liq. 345, 117833–117847 (2022).

Li, X. et al. The choice of ionic liquid ions to mitigate corrosion impacts: the influence of superbase cations and electron-donating carboxylate anions. Green Chem. 24, 2114–2128 (2022).

Long, W. J., Li, X. Q., Yu, Y. & He, C. Green synthesis of biomass-derived carbon dots as an efficient corrosion inhibitor. J. Mol. Liq. 360, 119522–119531 (2022).

Haldhar, R. et al. Anticorrosive properties of a green and sustainable inhibitor from leaves extract of Cannabis sativa plant: Experimental and theoretical approach. Colloid. Surface A 614, 126211–126222 (2021).

Sahin, E. A., Solmaz, R., Gecibesler, I. H. & Kardas, G. Adsorption ability, stability and corrosion inhibition mechanism of phoenix dactylifera extrat on mild steel. Mater. Res. Express 7, 016585–016596 (2020).

Xu, X. et al. Electrophoretic analysis and purification of fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotube fragments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 12736–12737 (2004).

Ye, Y. W., Zhang, D. W., Zou, Y. J., Zhao, H. C. & Chen, H. A feasible method to improve the protection ability of metal by functionalized carbon dots as environment-friendly corrosion inhibitor. J. Clean. Prod. 264, 121682–121693 (2020).

Wang, T. X. et al. Ionic liquid-assisted preparation of N, S-rich carbon dots as efficient corrosion inhibitors. J. Mol. Liq. 356, 118943–118958 (2022).

Berdimurodov, E., Verma, D. K., Kholikov, A., Akbarov, K. & Guo, L. The recent development of carbon dots as powerful green corrosion inhibitors: A prospective review. J. Mol. Liq. 349, 118124–118141 (2022).

Zeng, S. Y. et al. Synthesis of Ce, N co-doped carbon dots as green and effective corrosion inhibitor for copper in acid environment. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E. 141, 104608–104618 (2022).

Padhan, S., Rout, T. K. & Nair, U. G. N-doped and Cu, N-doped carbon dots as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel corrosion in acid medium. Colloid Surface A 653, 129905–129924 (2022).

Tang, W. W. et al. Facile pyrolysis synthesis of ionic liquid capped carbon dots and subsequent application as the water-based lubricant additives. J. Mater. Sci. 54, 1171–1183 (2019).

Ye, Y. W. et al. A high-efficiency corrosion inhibitor of N-doped citric acid-based carbon dots for mild steel in hydrochloric acid environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 381, 121019–121029 (2020).

Bhargava, G., Ramanarayanan, T. A., Gouzman, I. & Bernasek, S. L. Corrosion inhibitor –Iron interactions: A study combining surface science and electrochemistry. ECS Trans. 1, 195–206 (2006).

Zhao, S. J. et al. Green synthesis of bifunctional fluorescent carbon dots from garlic for cellular imaging and free radical scavenging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 17060–17066 (2015).

Xu, P. P., Wang, C. F., Sun, D., Chen, Y. J. & Zhuo, K. L. Ionic liquid as a precursor to synthesize nitrogen- and sulfur-co-doped carbon dots for detection of copper(II) ions. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 31, 730–735 (2015).

Wan, J. Y., Yang, Z., Liu, Z. G. & Wang, H. X. Ionic liquid-assisted thermal decomposition synthesis of carbon dots and graphene-like carbon sheets for optoelectronic. RSC Adv. 6, 61292–61300 (2016).

Guo, T. T., Zheng, A. Q., Chen, X. W., Shu, Y. & Wang, J. H. The structure-activity relationship of hydrophilic carbon dots regulated by the nature of precursor ionic liquids. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 554, 722–730 (2019).

Meng W. X., Bai X, Wang B. Y., Liu Z. Y., Lu S. Y. & Yang B. Biomass-derived carbon dots and their applications. Energy Environ. Mater. 1–21 (2019).

Wareing, T. C., Gentile, P. & Phan, A. N. Biomass-based carbon dots: Current development and future perspectives. ACS Nano 15, 15471–15501 (2021).

Mou, Z. et al. Scalable and sustainable synthesis of carbon dots from biomass as efficient friction modifiers for polyethylene glycol synthetic oil. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 14997–15007 (2021).

Li, Y. J. et al. Calcium-mobilizing properties of salvia miltiorrhiza-derived carbon dots confer enhanced environmental adaptability in plants. J. Sun ACS Nano. 16, 4357–4370 (2022).

Stepanidenko, E. A., Ushakova, E. V., Fedorov, A. V. & Rogach, A. L. Applications of carbon dots in optoelectronics. Nanomaterials-Basel. 11, 364–382 (2021).

Xiang T. F., Wang J. Q., Liang Y. L., Daoudi W., Dong W., Li R. Q., Chen X. X., Liu S. J., Zheng S. L. & Zhang K. Carbon dots for anti-corrosion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2411456–2411480 (2024).

Ye, Y., Yang, D. & Chen, H. A green and effective corrosion inhibitor of functionalized carbon dots. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 35, 2243–2253 (2019).

Li, F. T. et al. Improvement of carbon dots corrosion inhibition by ionic liquid modification: Experimental and computational investigations. Corros. Sci. 224, 111541–111553 (2023).

Ahmed, G. H. G., El-Naggar, G. A., Nasr, F. & Matter, E. A. N-doped and N, Si-doped carbon dots for enhanced corrosion inhibition of mild steel in acidic environment. Diam. Relat. Mater. 136, 109979–109989 (2023).

Wang, Q. H. et al. Protein-derived carbon dots as green corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in sulfuric acid solution. Diam. Relat. Mater. 145, 111135–111149 (2024).

Matter, E. A., El-Naggar, G. A., Nasr, F. & Ahmed, G. H. G. Facile synthesis of N-doped carbon dots (N-CDs) for efective corrosion inhibition of mild steel in 1 M HCl solution. J. Appl. Electrochem. 53, 2057–2075 (2023).

Ye, Y. W., Zhang, D. W., Zou, Y. J., Zhao, H. C. & Chen, H. A feasible method to improve the protection ability of metal by functionalized carbon dots as environment friendly corrosion inhibitor. J. Clean. Prod. 264, 121682–121693 (2020).

Qiang, Y. J. et al. Experimental and theoretical studies of four allyl imidazolium-based ionic liquids as green inhibitors for copper corrosion in sulfuric acid. Corros. Sci. 119, 68–78 (2017).

Chen, W. et al. Synthesis of graphene quantum dots from natural polymer starch for cell imaging. Green Chem. 20, 4438–4442 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Kilogram-scale synthesis of carbon quantum dots for hydrogen evolution, sensing and bioimaging. Chin. Chem. Lett. 30, 2323–2327 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Deep red emissive carbonized polymer dots with unprecedented narrow full width at half maximum. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906641–1906649 (2020).

Shuang, E., He, C., Wang, J. H., Mao, Q. X. & Chen, X. W. Tunable organelle imaging by rational design of carbon dots and utilization of uptake pathways. ACS Nano 15, 14465–14474 (2021).

Sun, D. et al. Hair fiber as a precursor for synthesizing of sulfur- and nitrogen-co-doped carbon dots with tunable luminescence properties. Carbon 64, 424–434 (2013).

Cao, S. Y. et al. Nitrogen-doped carbon dots as high-effective inhibitors for carbon steel in acidic medium. Colloid Surface A 616, 126280–126291 (2021).

Sheng, Z. H. et al. Catalyst-free synthesis of nitrogen-doped graphene via thermal annealing graphite oxide with melamine and its excellent electrocatalysis. ACS Nano 5, 4350–4358 (2011).

Li, W., Long, G., Chen, Q. & Zhong, Q. High-efficiency layered sulfur-doped reduced graphene oxide and carbon nanotube composite counter electrode for quantum dot sensitized solar cells. J. Power Source 430, 95–103 (2019).

Wang, C. et al. A strong blue fluorescent nanoprobe for highly sensitive and selective detection of mercury(II) based on sulfur doped carbon quantum dots. Mater. Chem. Phys. 232, 145–151 (2019).

Liu, Z., Ye, Y. W. & Chen, H. Corrosion inhibition behavior and mechanism of N-doped carbon dots for metal in acid environment. J. Clean. Prod. 270, 122458–122469 (2020).

Bhargava, G., Ramanarayanan, T., Gouzman, I. & Bernasek, S. Corrosion inhibitor Fe interactions: A study combining surface science and electrochemistry. ECS Trans. 1, 195–206 (2006).

Kowsari, E. et al. In situ synthesis, electrochemical and quantum chemical analysis of an amino acid-derived ionic liquid inhibitor for corrosion protection of mild steel in 1 M HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 112, 73–85 (2016).

Dutta, A., Saha, S. K., Adhikari, U., Banerjee, P. & Sukul, D. Effect of substitution on corrosion inhibition properties of 2-(substituted phenyl) benzimidazole derivatives on mild steel in 1 M HCl solution: a combined experimental and theoretical approach. Corros. Sci. 123, 256–266 (2017).

Cui, M., Ren, S., Zhao, H., Wang, L. & Xue, Q. Novel nitrogen doped carbon dots for corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 443, 145–156 (2018).

Khadiri, A. et al. Phenolic and non-Phenolic fractions of the olive oil mill wastewaters as corrosion inhibitor for steel in HCl medium. Portugaliae Electrochim. Acta. 32, 35–50 (2014).

Popova, A., Sokolova, E., Raicheva, S. & Christov, M. AC and DC study of the temperature effect on mild steel corrosion in acid media in the presence of benzimidazole derivatives. Corros. Sci. 45, 33–58 (2003).

Hegazy, M. A., Abdallah, M., Awad, M. K. & Rezk, M. Three novel di-quaternary ammonium salts as corrosion inhibitors for API X65 steel pipeline in acidic solution. Part I: Experimental results. Corros. Sci. 81, 54–64 (2014).

Cui, M. J., Qiang, Y. J., Wang, W., Zhao, H. C. & Ren, S. M. Microwave synthesis of eco-friendly nitrogen doped carbon dots for the corrosion inhibition of Q235 carbon steel in 0.1 M HCl. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 16, 151019–151041 (2021).

Wang, J. H. et al. Inhibition effect of monomeric/polymerized imidazole zwitterions as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in acid medium. J. Mol. Liq. 312, 113436–121146 (2020).

Khaled, K. F. The inhibition of benzimidazole derivatives on corrosion of iron in 1 M HCl solutions. Electrochim. Acta 48, 2493–2503 (2003).

Zarrok, H. et al. Corrosion control of carbon steel in phosphoric acid by purpald–weight loss, electrochemical and XPS studies. Corros. Sci. 64, 243–252 (2012).

Cao, S. Y. et al. Task-specific ionic liquids as corrosion inhibitors on carbon steel in 0.5 M HCl solution: An experimental and theoretical study. Corros. Sci. 153, 301–313 (2019).

Qiang, Y. J., Zhang, S. T., Xu, S. Y. & Yin, L. L. The effect of 5-nitroindazole as an inhibitor for the corrosion of copper in a 3.0% NaCl solution. RSC Adv. 5, 63866–63873 (2015).

Sigircik, G., Tuken, T. & Erbil, M. Assessment of the inhibition efficiency of 3, 4-diaminobenzonitrile against the corrosion of steel. Corros. Sci. 102, 437–445 (2016).

Kokalj, A. Corrosion inhibitors: physisorbed or chemisorbed?. Corros. Sci. 196, 109939–109953 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52371055), Weifang College Doctoral Research Foundation (No. 209-44122020), the Nature Fund Project of Shandong Province (No. ZR2011EL003), and the Science and Technology benefiting the People Program of Weifang Hi-Tech Zone (No. 2019KJHM19).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shuyun Cao: Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Writing-original draft. Funding acquisition. Yang Zhao: Resources, funding acquisition. Yubao Cao: Formal analysis. Yongwei Li: Formal analysis. Haodong Tan: Data curation, Investigation. Hong Wang: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, S., Zhao, Y., Cao, Y. et al. Ionic liquid-assisted biomass-derived N, S-doped carbon dots with enhanced corrosion inhibition. Sci Rep 15, 23056 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04444-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04444-z