Abstract

The brick manufacturing process contributes to the presence of heavy metals, particularly in the microenvironment surrounding the kilns. The current study aimed to investigate the effects of heavy metal-containing brick kiln emissions on the reproductive health and hematobiochemical parameters of brick kiln workers in Layyah, Pakistan. The current study involved (n = 300) workers and (n = 200) non-workers. Demographic data, health history and body mass index (BMI) were assessed. Blood samples were collected to determine heavy metal concentrations, hematological profiles, and liver function tests. A significant decrease in BMI (Kg/m2) and blood sugar (mg/dL) levels, while an increase in systolic blood pressure (SBP; mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP; mmHg) among workers was recorded. Analysis of blood samples revealed elevated levels of lead (µg/dL) and cadmium (µg/dL) in workers compared to non-workers. Increased white blood cells (1 × 103), platelet count (1 × 103), alkaline phosphatase (U/L), alanine transaminase (U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (U/L), and bilirubin total (mg/dL) levels were noted. Reactive oxygen species (μmole/min) and thiobarbituric acid (mM/mg/protein) levels increased while decreased haemoglobin (g/dL), red blood cells (1 × 106), albumin (g/dL), protein (g/dL), catalase (U/min), superoxide dismutase (U/min), peroxidase (nmole) and reduced glutathione (mM/l) were evident among workers as compared with the non-workers. Significant increase in total cholesterol (mmole/L), low-density lipoprotein (mmole/L) and triglyceride (mmole/L), while a substantial decrease in high-density lipoprotein (mg/dL), immunoglobulin M (g/dL) and testosterone levels (ng/ml) was noted among workers as compared with non-workers. Pearson correlation between lead and antioxidants (GSH, SOD) levels was significant. The present study examines the increasing heavy metal burden in the blood of brick kiln workers, which causes reproductive health issues due to higher oxidative stress conditions. The present study highlights valuable awareness regarding the consequences of heavy metal exposure on the health of brick kiln workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brick manufacturing is a large and established industry in several Asian countries1. The manufacturing process releases pollutants such as carbon oxides, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, organic matter, dust, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and hydrogen sulfide, which can harm both humans and the environment2. Brick kilns are also significant sources of greenhouse gases3. There are approximately 300,000 brick kilns worldwide, with 75% of them located in Pakistan, Bangladesh, China and India4. Brick kilns can be divided into two main types: continuous kilns and intermittent kilns. Examples of continuous kilns include Hoffmann kiln, Tunnel kiln, Bull’s trench kiln (BTK), Zigzag kiln and vertical shaft brick kiln (VSBK)5.

In Pakistan, brick kilns can be broadly categorised into two types: Traditional Brick Kilns (TBK) and Contemporary Brick Kilns (CBK)6. The raw substances used for making bricks are sediments, clay or soil from rivers, which contain fine particles7,8. Many brick kilns use fuels like slack coal, Assam coal, lignite and other sources that have high sulfur content and ash content ranging from 25 to 30%. In terms of fuel composition, approximately 70% of coal, 24% of sawdust, and the residual 6% consists of wood and other materials are used by brick kilns7,9. Brick manufacturers frequently use cheaper waste products such as used old tyres, motor oil, plastics, and rubbish as an alternative supply10. The brick kiln manufacturing process also contributes to the presence of heavy metals, particularly in the microenvironment surrounding the kilns, affecting vegetation, soil, and humans11. Brick kilns that use diesel for combustion can produce harmful substances known to be genotoxic, cytotoxic, and carcinogenic, causing damage to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and cells. Workers in such kilns may also be exposed to heat and radiation, which might result in genetic changes. DNA strand breakage, DNA–protein cross-links and multifactorial lung disorders such as radiation pneumonitis, fibrosis, and widespread alveolitis are all possible causes12. Furthermore, excessive amounts of heavy metals in the soil lead to severe health problems, including neurological, hematological, gastrointestinal, and immunological difficulties, as well as neoplasms. Heavy metals mainly affect the body by interacting with heme-production enzymes, thiol-containing antioxidants, and enzymes. Both silica and heavy metals can produce free radicals and cause oxidative stress12. Heavy metals such as lead in brick kiln soil can negatively impact the male reproductive system. They can influence the hypothalamic-pituitary–gonadal system or directly affect spermatogenesis, leading to decreased sperm quality13. These harmful substances also hurt the human reproductive system, resulting in infertility, birth abnormalities, spontaneous abortions, and early miscarriages. The male reproductive system is particularly affected during spermatogenesis. Furthermore, these pollutants can cause immune system disruption by creating excessive quantities of reactive oxygen species, which can cause cell damage through decomposition of protein, nucleic acid degradation or lipid peroxidation13. Long-term cadmium exposure can cause renal illness, lung damage, and weaker bones because it accumulates in the kidneys14. Soluble Cadmium salts can be hazardous to many organs, including the lungs, liver, heart, kidneys, brain, testes, and central nervous system. Cadmium does not produce free radicals directly, but it induces lipid peroxidation in tissues shortly after exposure15.

Jahan et al. (2016) conducted a study in Punjab (Rawat) for which male workers were recruited from Tarlai, District Rawalpindi, and their biochemical profiles were evaluated to determine the effect of brick kiln emissions on reproductive health16 and another survey was conducted and different brick kiln sites from District Rawalpindi (Potohar) were selected17. The current study selected participants from different regions with different climatic conditions. Our objective was to evaluate the alterations in blood levels of toxic metals attributable to exposure to emissions from brick kilns. We employed a quantitative research design and recruited a representative sample of workers from brick kilns in Layyah District. Further, atomic absorption spectroscopy was performed to assess the level of heavy metals in their blood. Likewise, lipid profile, antioxidant enzyme tests, various biochemical tests and hormone tests were performed to assess the effects of heavy metal exposure on the overall healthiness of brick kiln workers. A comprehensive survey questionnaire was developed to collect data on the workers’ demographic, socio-economic, and occupational characteristics. Our research aims to identify potential health hazards associated with long-term exposure to brick kiln work emissions like heavy metals (Lead and Cadmium) and potentially promote the awareness of unsafe occupational conditions for the well-being of workers in the industry.

Methods

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Bio-Ethical Committee of the Department of Zoology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad and has been assigned protocol #BEC-FBS-QAU2023-551. Additionally, the participants in the study willingly agreed to participate, and informed consent was obtained from all the participants and/or their legal guardians. The study was carried out following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Description of the study area

An investigation was conducted and different brick kiln sites in District Layyah in southern Punjab. District Layyah contains 208 functional brick kilns of which 110 brick kilns are in the Chaubara and Karor Lal Esan, that was selected on the basis of production capacity, functionality, nearness to communities and operation throughout the year. The eastern part of the district is characterised by a sandy desert, which leads to sandstorms due to extreme temperatures during the summer season. The climate in this area is dry, and rainfall is infrequent. Summers are long and humid, making up about half of the year, while winters are short. Throughout the year, the temperatures range from 7 to 41 °C18. Approximately 48 brick kilns were visited, out of which 28 brick kiln owners agreed to participate in the study. All the brick kilns were similar in that either they were Fixed Chimney Bull’s Trench Kilns or used zigzag technology for making bricks, whilst the number of employees varied based on ethnicity and gender. In certain kilns, only male workers were dominant, whilst others had women and children or only Pathan/Punjabi workers. The rate of participation was quite low and varied among different kilns due to multiple reasons, i.e. certain brick kilns were not registered and therefore their owners did not agree to participate; the prevalence of bonded and child labour; and illiteracy as well as the occurrence of superstitious beliefs. More detailed information on the study area can be found in our previous work. To facilitate the research, the researchers utilised Geographic Information System (GIS) software, especially Arcgis, to develop sampling sites on a map (Fig. 1).

Questionnaire data

The researcher carefully studied the current literature on the issue before performing the study and designing a questionnaire. They also developed a questionnaire based on the variables and indicators used in the Demographic & Health Surveys (DHS) (https://dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/DHS.cfm). The questionnaire was formed in a “mixed” style, meaning it had both open-ended and closed-ended questions to collect qualitative and quantitative data. The initial portion of the questionnaire collected socio-demographic information from participants such as their height, weight, age, status, marital status, employment position, wealth quintile and previous medical history. The following section of the questionnaire covered a variety of aspects, such as work history, any previous diseases or health issues, smoking status or habits, reproductive history, the nature of the job, the extent of exposure to brick kiln pollutants and the participants’ knowledge of other diseases associated with such work. By using this well-structured questionnaire, the researchers were able to collect valuable data, both in qualitative and quantitative forms, to thoroughly explore the impact of brick kiln contaminants on the health and reproductive well-being of male workers in selected areas in Punjab’s District Layyah.

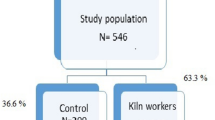

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined using Eq. (1), as previously published19,20. Because the study was concerned with people’s health, the sample size was determined using a 5% level of significance and a 10% margin of error based on the number of healthy and unhealthy workers. This formula resulted in a sample size of 215.

p = Brick kiln workers with health issues.

q = Brick kiln workers with no health issues.

L = The level of relevance.

Participants selection

Data collection and blood sampling took place from January 2023 to April 2023 at different brick kiln locations, including Pahar Pur, Kot Sultan, Chowk Azam, Noshera, and Karor Lal Esan in district Layyah. The participants in the study willingly agreed to take part and signed consent forms. Men do most of the activities associated in the brick kiln industry, such as loading, unloading, baking and fire. After gathering the necessary information from the participants, the males were separated into two distinct groups based on their characteristics. The first group was labelled as Control males (CM, n = 300). These were individuals who did not work in brick kilns and served as the control group for comparison. The second group was comprised of male workers who were actively working in brick kilns. This group was referred to as brick kiln male workers (AM, n = 300).

Interviews

The study participants were questioned using a systematic and verified questionnaire. The questionnaire aimed to collect demographic information to understand participants’ backgrounds and health influences. The demographic information collected through the questionnaire included height, weight, age, education level, family size, marital status, any record of diseases in the family, current medications, smoking habits, duration of exposure to brick kiln emissions, the amount of time spent on the job whether they used protective equipment while working and the nature of their job tasks.

Blood samples collection

Blood samples were taken from both brick kiln workers and control members. A 5 mL syringe with a 16 Ga needle was used to draw blood which was then divided into four portions. Three of these parts were placed in tubes coated with EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid: a chemical that helps preserve the blood). The blood in the EDTA tubes was used for three different purposes. First, it was used for complete blood count (CBC) to assess various blood parameters. Second, the blood in these tubes was used to determine the levels of heavy metals using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) as conducted by21. Blood in the third tube was separated into plasma and kept at -20 °C) till further analyzed. The fourth part of the blood was collected in yellow-top tubes to conduct liver function tests i.e. (ALP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), bilirubin Total and albumin, by following the previous protocol22.

Body mass index (BMI)

BMI of all participants was determined by dividing their weight in kilograms by the square of their height in meters4.

1.Underweight body group (BMI < 18.5).

2.Normal body weight group (BMI < than 24).

3.Overweight body group (BMI > 24).

4.Obese body weight group (BMI > 30).

Measurement of blood pressure

Blood Pressure was measured while workers were sitting after a 5-min rest interval and the stated result is the average of three measures obtained via a mercury-based Sphygmomanometer on the right arm.

Measurement of blood sugar

Life Check TD-4141 glucometer was used to measure the blood glucose levels. A test strip containing a drop of blood from each participant was inserted into the glucose meter, and measurements in mg/dL were displayed on the instrument’s screen23.

Hematological analysis

Blood samples were stored in EDTA tubes and used for hematology analysis. The hematology analysis (lymphocyte count (LYM#), granulocytes count. haemoglobin (HGB), total hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH, platelet count was conducted using an automated haematology analyzer (VBC50A, Seamaty, China).

Analysis of heavy metals

The present study’s methodology was based on the previous protocol21. All the equipment to be used was soaked in a 10% nitric acid solution overnight. Then, the equipment was washed with a 69% nitric acid solution and dried using absorbent paper. The equipment was kept overnight after washing. 5 ml of 69% nitric acid was added to 0.5 ml of whole blood until the solution turned transparent. This is known as pre-digestion. Manual digestion was performed by boiling the mixture of whole blood and nitric acid at 400 °C until the solution volume was reduced by half. After that, the samples were filtered with the help of a Whatman filter in this regard to eliminate solid particles. The samples were then filtered via Whatman filter paper to remove any solid particles. Consequently, distilled water was added for its filtration to reach a consolidated volume of 15 mL, and Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) was carried out for heavy metal analysis.

Atomic absorption spectroscopy

For heavy metal determination, acid digestion for blood samples was performed following a previously described protocol and the processed samples were analyzed using a Fast Sequential Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (Varian, AA240FS, USA). The instrument was calibrated by using multiple concentrations from 1 to 50 ppm and calibrations were done for each metal using the formula (C1V1 = C2V2), and a series of standards run to deliver a calibration curve17.

Biochemical analysis

Following antioxidant enzymes and oxidative stress marker enzymes in blood plasma were determined using a UV Spectrophotometer (Agilent 8453).

Catalase (CAT) activity

Based on the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide, CAT activity was analyzed by following the protocol of afsar et al. with minor modifications24. In brief, the CAT reaction solution consists of 1.5ml of 50 mM of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5), 300 μl of 30 mM H2O2 and 25 μl of plasma sample, Change in absorbance was noted for one minute at a wavelength of 240 nm by spectrophotometer. A change of 0.01 in absorbance for one minute was taken as one unit of CAT activity.

Superoxide dismutase activity (SOD)

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) was determined using the method by25. Briefly, the reaction mixture contains 1 ml sodium pyrophosphate buffer (concentration; 52 micromolar and pH at 7.0), 100 µl phenazine methosulphate (186 µM) and 20 µl of plasma sample. The reaction was initiated by adding 200 µl of NADH (780 µM). 1 ml of glacial acetic acid was added after 1 min to stop the reaction. The amount of chromogen formed was measured by recording color intensity at 560 nm. Results are expressed in units/mg of protein.

Peroxidase activity (POD)

POD activity was measured by following the previous protocol26 with slight modifications. In short, a reaction mixture containing 0.1 mL plasma, 0.1 mL guaiacol (20 mM), 0.3 mL H2O2 (40 mM), and 2.5 mL phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.0) was used. The absorbance was calculated after one minute of incubation at 470 nm. The POD activity was measured as an absorbance change of 0.01 per unit per minute.

Reduced glutathione (GSH)

The protocol of20 was followed to determine glutathione (GSH) levels. The reaction mixture was prepared by mixing 100 μl of plasma sample with 800 μl of deionized water and 100 μl of 50% trichloroacetic acid. After stirring for 10–15 min, the mixture was centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 rpm. 400 μl supernatant was collected and mixed with 800 μl tris–EDTA buffer (0.2 M, pH 8.9) and 20 μl DTNB reagent. 0.0307 g of glutathione (GSH) was mixed in 100 ml of 0.4 M solution of EDTA. Five minutes adding DTNB, the absorbance of both standard and blood plasma samples was measured at a wavelength of 412 nm.

Estimation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Reactive oxygen species (ROS levels were measured following the previous method27. Initially, two solutions were prepared: R1 consisted of 100 g/ml DEPPD in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.8), while R2 contained 4.3 M ferrous sulfate in sodium acetate buffer. A standard solution of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was used for the calibration curve. The amount of ROS in the samples was calculated using a UV spectrophotometer (Agilent 8453). The readings were construed based on the predetermined calibration curve.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Malondialdehyde (MDA) in plasma was measured using the TBA technique28 A plasma sample (0.1 mL) was mixed with 0.29 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and 0.1 mL of 100 mM ascorbic acid. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C in a shaker for one hour. To halt the reaction, 0.5 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid was added to stop the reaction. Subsequently, 1 ml of 0.67% trichloro barbituric acid was included, and the mixture was incubated again for 20 min at 95 °C in the water bath. The samples were then cooled in an ice bath and centrifuged at 2500 × g for 10 min to separate the supernatant. The optical density of both the samples and the reagent blank was recorded at 535 nm using a spectrophotometer (Agilent 8453). The concentration of TBARS was calculated and expressed as TBARS per minute per millilitre of plasma at 37 °C using a designated formula.

Total protein measurement

The total protein content in the serum was measured using a kit provided by AMP kits from AMEDA Labordiagnostik GmbH (Austria).

Lipid profile

Plasma level of triglyceride (Cat # REFBR4501), total cholesterol (Cat # REF104989993203), High-density lipoprotein (HDL; Cat # 104989993193) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL; Cat # BR3302) was determined with the help of AMP diagnostic kits (AMEDA Labordiagnostik GmbH, Austria) on chemical analyzer by following the instruction provided by the manufacturer on the kit.

IgM

To determine immunoglobulin levels in plasma a protocol described by Gonzalez and colleagues was followed29. Following this method, Immunoglobulin was separated by precipitation from plasma, by mixing 100 µL (0.1 mL) of plasma with 100 µL (0.1 mL) of polyethylene glycol (12%) 1:1. Under constant shaking in an incubator shaker, the solutions were incubated at 25 °C for 2 h and then centrifuged at 7000 × g for 10 min. The protein contents’ optical density (OD) was measured at 660 nm. The total IgM level was calculated by subtracting proteins of the supernatant from the total proteins in the plasma.

Hormonal analysis

The levels of Testosterone in blood plasma were quantitatively assessed using the Testosterone Elisa test kit (Bioactive, JTC, Germany). The tests were performed according to the protocol included with the kit.

Statistical analysis

The data are shown as the mean along with the standard error of the mean (Mean ± SEM). Descriptive statistics for socio-demographic variables were calculated, including mean, standard deviation, and percentage. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used in SPSS 22 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences 22) to compare participants in the test group with those in the control group regarding heavy metal exposure, blood parameters, liver function tests, antioxidant enzyme profiles, and hormone concentrations. To analyze the relationship between lead levels and biochemical profiles, Pearson’s correlation was applied using STATA 14 (statistics and data 14).

Results

Area distribution and language of workers

Brick kiln workers in District Layyah, Punjab, come from various towns and tehsils within the district. (Fig. 2A). The number of workers at each brick kiln site varied, and the subjects working there spoke different languages, including Saraiki, Punjabi, and Pashto (Fig. 2B).

Sociodemographic data

The brick kiln workers had an average age of 38.02 ± 0.76 years, while the control individuals had an average age of 40.04 ± 0.98 years. Our findings revealed that most men working at brick kiln sites had a healthy weight. However, a small percentage were classified as obese (1.6%), and 8.6% were overweight. Additionally, 32% fell into the overweight category. Among these brick kiln workers, a significant proportion (85.3%) were married, while the remaining 14.7% were unmarried. Regarding sleep duration, most brick kiln workers reported sleeping routine between 5 to 10 h (93.3%). Furthermore, about 52.4% of the workers had not received formal education. When it came to food preferences, an overwhelming majority (96%) of brick kiln workers preferred vegetables as their primary dietary choice (Table 1).

Health history of brick kiln workers

A significant portion of the workforce, accounting for 35%, reported experiencing bone pain likely linked to their demanding workloads. In addition to musculoskeletal discomfort, many workers are plagued by a range of troubling symptoms, including persistent fever, chest congestion, shortness of breath, and gastrointestinal disturbances. Alarmingly, between 11 and 13% of these individuals also suffer from respiratory issues such as asthma and chronic coughing. Those toiling in brick kilns face an array of health challenges, and the prevalence of various medical conditions is detailed in Table 2.

Work history of brick kilns workers

The people in this group were employed at very low wages, earning between PKR 10,000 to 20,000 per month. A majority (77%) of them were getting salaries in the range of 10,000 to 15,000 PKR. Out of the 300 workers, 57.7% worked as moulders, 23.7% were carriers, 16% were bakers and 2.6% held the position of munshis (accountants). On average, these individuals had been living near brick production sites for around 37 years and their job tenure averaged at 15 years. These workers faced exposure to various harmful substances such as smoke, smog, dust and fuel. The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) was not a common practice among the kilns visited. None of the male workers were observed using any form of PPE at their workplace.

Smoking status

A significant portion of the workers (53.7%) were found to be addicted to tobacco, consuming it in different forms such as cigarettes, Naswar (a mixture of calcium oxide, tobacco leaves, and wood ash, a smokeless tobacco product), Hokkah (a tobacco mixture in water/modern form Sheesha) and opium (a dried latex from opium poppy seed capsules). The average age at which these addictions began was 20 years. Breaking down the numbers, 12.3% of workers smoked 1 to 10 cigarettes, 11.3% used one packet of Naswar, 6.3% indulged in Hokkah 6 to 10 times and a small 0.6% were addicted to opium (Table 3).

Heavy metals

A significant rise in the level of lead was evident in the male worker group (8.56 ± 0.03 µg/dL) in contrast to the control group (1.37 ± 0.03 µg/dL). Male workers showed significantly greater amounts of cadmium (Cd) in their blood (p = 0.002) than control individuals (Fig. 3).

Body mass index, blood sugar and blood pressure

In the control group, the mean value of BMI was (24.71 ± 0.23 kg/m2) while among brick kiln workers, it was (20.75 ± 0.22 kg/m2) and this difference was determined to be statistically significant with a p-value of p = 0.001 (Fig. 4a). Among the control subjects, the blood sugar level was measured at (90.09 ± 0.22 mg/dL) while for brick kiln workers, it was notably lower at (83.84 ± 0.20 mg/dL) (Fig. 4b). In control, the average SBP was (105.50 ± 0.080 mmHg) while among brick kiln workers it was (123.43 ± 0.073 mmHg). In the control group, DBP was (69.48 ± 0.07 mmHg) while among workers it was (89.000 ± 0.08 mmHg) (Fig. 4c,d).

Blood parameters

The results of the complete blood analysis revealed significant differences in the white blood cell counts between the control and worker subjects. An evident increase (p = 0.021) in lymphocyte count (LYM#) in workers compared to the control group. A high increase in lymphocyte percentage (LYM%) was observed in brick kiln workers with p = 0.001. A highly significant increase in granulocyte count (GRA#) was observed among the exposed group with a p-value of p = 0.002. Percentage Granulocytes (GRA%) concentration increased from (48.37 ± 0.51%) to (58.34 ± 0.53%) in the exposed group. Workers’ haemoglobin (HGB) levels were significantly lower (p = 0.001) than those of the control group. A substantial decrease in the quantity of red blood cells (RBCs) was seen among brick kiln workers, with a p-value of 0.001. Brick kiln workers saw a substantial reduction in total hematocrit (HCT) concentration (p-value < 0.001). Male workers had significantly lower mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) than the control group (p-values = 0.002 and 0.001, respectively). Male workers showed significant increases in red cell distribution width-standard deviation (RDW-SD) and red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation (RDW-CV), with p-values of p < 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively, compared to the control group. The exposed group showed a substantial decrease in mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) (p-value = 0.002). Workers had a significantly higher platelet count (PLT) than the control group (p-value = 0.001). Significant increases in mean platelet volume (MPV) and Platelet Distribution Width (PDW) were detected (p-values < 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively). Plateletcrit (PCT) concentration increased from (0.17 ± 0.0002%) to (0.22 ± 0.003%), and Platelet-large cell ratio (P-LCR) concentration decreased from (25.30 ± 0.41%) to (13.65 ± 0.26%) in the exposed group (Table 4).

Liver function tests

Workers had a substantial rise in ALP levels compared to the control group (p-value = 0.001). The exposed group showed significantly higher levels of ALT and AST (p-values < 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively). Workers had a significant rise in bilirubin levels from 0.47 ± 0.24 mg/dL to 1.94 ± 0.90 mg/dL. Moreover, brick kiln workers experienced a significant reduction in Albumin levels with a p-value of p = 0.003. There was a highly significant decrease in Protein levels among brick kiln workers (p = 0. 001) (Table 5).

Lipid profile

Among the control subjects, the Total Cholesterol level was measured at 243.68 ± 4.59 mol/L, while for brick kiln workers it was notably higher at (304.54 ± 4.61 mol/L). The levels of triglycerides were (127.27 ± 2.00 mol/L) for brick kiln workers and (315.47 ± 2.58 mol/L) for control males. Workers had significantly higher LDL levels (p < 0.001) than the control group, whereas HDL levels decreased significantly among workers with a p-value (p = 0.001) (Table 4).

Biochemical analysis

Biochemical analyses revealed a significant reduction (p = 0.001) in SOD levels, from 16.04 ± 0.04U/min in the control group to 13.81 ± 0.05 U/min in the worker group. A substantial increase (p = 0.004) in ROS number was seen in the worker group as compared to the control group. The mean serum POD level for the worker group was (19.52 ± 0.042 nmol) with a significant level of p = 0.016 as compared to a control group with a mean (22.72 ± 0.049 nmole). Significant increases in TBARS with p-values of p = 0.004 were observed in male workers when compared to the control group. A significant decrease in GSH with a p-value of p = 0.001 was found in the exposed group. A significant increase in CAT (p = 0.004) was seen in workers compared to the control group (Table 4). A significant decrease in IgM (g/dL) with a p-value of p = 0.007 was found in the exposed group (Table 4).

Hormonal analysis

The concentration of testosterone in the plasma of the workers group presented by the mean value of (1.08 ± 0.04ng/ml) was significantly decreased (p = 0.001) from that of the control group (1.40 ± 0.05ng/ml) (Table 5).

Pearson correlation results

There was a substantial negative correlation between Lead and GSH (r = –0.231, p = 0.01) and, A positive correlation was found between lead and SOD (r = –0.2090, p = 0.003). There were no significant correlations between lead and CAT (r = –0.02, p = 0.71), POD (r = 0.0296, p = 0.67), ROS (r = –0.078, p = 0.27), TBARS (r = 0.102, p = 0.14). Table 5 provides the inter-correlations among the parameters. For example, there was a significant positive correlation for SOD with POD (r = 0.47, p = 0.000) and TBARS (r = 0.43, p = 0.000). There was a negative correlation between SOD and GSH (r = −0.29, P = 0.000) (Table 6).

Discussion

The current study reports on the demographic styles, inherent metal profile, and several health parameters of brick kiln workers at Layyah, Punjab. This is a novel report, merging an exclusive set of techniques and methods to depict a brick kiln community, precisely males. Our findings revealed that most men working at brick kiln sites had a healthy weight. However, a small percentage were classified as obese (1.6%), and 8.6% were overweight. Additionally, 32% fell into the overweight category. Among these brick kiln workers, a significant proportion (85.3%) were married, while the remaining 14.7% were unmarried. Regarding sleep duration, most brick kiln workers reported sleeping routine between 5 to 10 h (93.3%). Furthermore, about 52.4% of the workers had not received formal education17.

The present study showed that male brick kiln workers experienced various health issues such as body pain, asthma, allergies, cough, chest tightness, shortness of breath, fever, backbone pain, tuberculosis, kidney problems, and hepatitis. Those exposed to high levels of PM (particulate matter) over extended periods were particularly prone to skin problems30. Long-term exposure to PM negatively affects the outer skin layer by disrupting cholesterol levels in the epidermis31. Respiratory problems were also prevalent among workers experiencing frequent cough (50%), chronic cough (11.6%), persistent phlegm (11.6%), regular phlegm (21.6%), chronic wheezing (15%), shortness of breath of grades I and II (38.3%), frequent wheezing (20%) and self-reported asthma (3.3%)4. The occurrence of lower back pain and tenderness was notably elevated among workers engaged in tasks like spading and mould evacuating32. A study in Nepal found that brick kiln employees had pain at a rate of 58–73%, making them eight times more likely to suffer discomfort than non-brick workers33. Unfortunately, workers were not using protective equipment like masks or gloves, and they molded bricks using their bare hands. This increased their health risks by exposing them to numerous toxins by inhaling, digesting or direct skin contact. Among the 300 individuals who participated in the present study, a significant number of adult male workers were addicted to various substances like cigarettes, naswaar and hukkah. Previous research also found a high prevalence of smoking among brick kiln workers4. This condition indicates that workers in brick kiln industries are susceptible to lung disorders such as silicosis, pneumoconiosis, and musculoskeletal disorders34. The findings of the present study depicted that 54% of brick kiln employees were illiterate, which is consistent with previous research where 84% of brick kiln workers were found to be illiterate35. In a current study, AAS was used to analyze heavy metals in blood samples. All samples from brick kiln workers included significantly higher levels of Cd and Pb than the control group. A current study analyzed heavy metal levels in whole blood and found a considerable rise in heavy metal levels among workers exposed to pollutants from brick kilns. Notably, there was an excessive amount of cadmium. Previous research has linked occupational or environmental exposure to cadmium with an increased risk of cancers in various organs such as the pancreas, lung, breast, prostate, nasopharynx, and urinary bladder36. Furthermore, the results from AAS (atomic absorption spectroscopy) indicated higher levels of lead in the human subjects studied. Lead poisoning in humans leads to detrimental effects on the nervous, renal, and hematologic systems. Symptoms can also include hypertension, anorexia, abdominal pain, vomiting and infertility. Humans typically absorb lead through dietary intake, respiration, and the gastrointestinal system. However, in occupational exposures, breathing is a major route of entry37. A significant decrease in BMI was noticed among the participants working at the brick kilns. The low BMI values among these workers suggest that they have poor health conditions and weakened immune systems which could make them more susceptible to various issues such as allergies, musculoskeletal problems, respiratory disorders, stomach issues, liver, and kidney problems. The findings of the present study were supported by a previous study by Li et al. (2022) which found an inverse association between heavy metals (Pb, Cd, and Hg) and the risk of peripheral or abdominal obesity38. Higher concentrations of lead and cadmium in the environment are associated with higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures. The current findings showed an increase in SBP and DBP in workers as compared to control. These findings are supported by Ataro et al. (2018) where an increase in SBP and DBP was noted among garage workers Harar, eastern Ethiopia as compared to control39. Another study finding suggested that an increase in SBP and DBP occurred in occupational workers subjected to lead as compared to control40. The findings of the present study revealed a decrease in blood sugar levels among the Pb battery recycling plant workers as compared to the control group. This statement is consistent with the results of Kshirsagar et al. (2015) where battery manufacturing workers of Western Maharashtra (India) also exhibited decreased blood sugar levels in comparison to controls41.

The analysis of blood parameters in the current study showed a decrease in the levels of RBCs, Hb, MCV, MCH and MCHC along with a rise in levels of WBC, LYM, PLT and MPV. These modifications might be caused by heavy metals released from brick kilns. A study conducted by Kargar-Shouroki et al. (2023) on Iranian battery workers similarly reported significant decreases in RBCs, Hgb, MCV, MCH and MCHC along with a rise in total WBC count compared to controls42. Additionally, Kshirsagar et al. (2016) observed significantly reduced levels of Hb, MCHC, MCV, MCH and RBC count, accompanied by an elevated WBC count, in battery manufacturing workers of western Maharashtra, India when compared to a control group43. Dobrakowski et al. (2016) reported an increased count of lymphocytes, leading to a rise in WBC count despite a decrease in granulocyte count due to lead exposure among occupational workers44.

Oxidative stress is identified as a key indicator causing the toxicity of heavy metals. ROS are free radicals that are continuously generated during normal oxidative metabolism. Additionally, they can be produced by various xenobiotic substances including heavy metals45. It was found in a recent study that workers who were exposed to such substances had lower levels of antioxidant enzymes (GSH, SOD, CAT, and POD) in their bodies as well13,20. This states that the workers who are exposed to heavy metals and other pollutants are a massive cause of oxidative stress which is massively responsible for negative health issues. The findings of the present study are similar to the previous research conducted by Onah et al. (2023) It was identified that a significant decrease in blood activity of antioxidants enzymes namely, GST, SOD, and CAT, as well as a significant rise in serum MDA levels in lead-exposed groups46. The same is the case with the recent investigation that an increase of TBARS and ROS identified among the workers as compared to non-workers. Further, the investigation of this study was confirmed in the light of Igharo et al. (2020) the role of heavy metal toxicity on bronze workers as compared to an increase in ROS was minimally highlighted but the rise of MDA and a decrease in total antioxidant capacity (TAC)47.

Many researches have shown that oxidative stress is a vital part of the relevant mechanism of Cd toxicity in humans48. Goyal et al. (2021) further it was investigated that low level of occupational exposure to Cd is a responsible cause of oxidative enzymes and stress in workers, owing to a reduction in antioxidant enzymes and an increase in lipid peroxidation as well stated by49. The findings of the present study explained a considerable increase in levels of ALP, ALT, AST, and total bilirubin as well. In a previous study conducted by Onah et al. (2023) elevated serum ALT and AST activities were observed in lead recycling factory workers in Anambra State, Nigeria indicating hepatocellular damage while increased serum ALP and GGT (gamma-glutamyl transferase) were also seen46. Mazumdar & Goswami (2014) reported similar outcomes in Indian plastic industry workers50. Furthermore, our study found a reduction in albumin and protein levels in the working group. Our findings are supported by Al Salhen (2014) where cement industry workers’ of Libya plasma concentrations of total protein, albumin and globulin were found to be significantly lower51. The findings of the present study revealed a rise in plasma levels of total cholesterol, LDL, and triglycerides along with a reduction in HDL. Study shows that exposure to Cd can lead to changes in lipid metabolism and contribute to the development of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) such as hypertension, cardiac arrest, atherosclerosis, and stroke47. These results were consistent with David et al. (2020) who found higher levels of total cholesterol, LDL, and TG in female brick kiln workers of Rawat (Phambli town, District Rawalpindi) when compared to the non-worker group52. Similarly, Firoozichahak et al. (2022) the research investigated and reported that lower HDL levels and higher LDL levels were exposed in subjects working in lead mine complex in Iran and then compared to non-exposed subjects as stated by53. Moreover, previous research has shown that perennial exposure to cadmium can raise both total cholesterol and LDL concentrations among waste electrical and electronic workers in Benin City of South-South Nigeria as stated by47.

The assessment of IgM in the ambit of the present study highlighted that there is a significant reduction in levels among these two groups namely brick kiln workers and non-workers. It was found in this study that the decrease in IgM levels was due to higher levels of lead and cadmium. Moreover, it was investigated that lower IgM levels were concerned with higher lead levels as noticed by earlier researchers54.

We recorded a lower amount of testosterone in the blood plasma of brick kiln workers as compared to the control group. The decrease in testosterone levels might be ascribed to the high quantity of heavy metals in their blood, which could lead to an increase in the formation of ROS, resulting in reproductive dysfunction. The impact of Cadmium as an endocrine disruptor is vitally known due to the negative effects of reproduction. It has been observed that the effects of steroidogenesis and spermatogenesis are both experimental in humans and animals as well. The disrupting effects of androgen and estrogen receptors as stated by55. Further, Pb exposure has also been concerned with subclinical testicular damage and the formation of ROS as well. Moreover, such variables are believed to be harmful to spermatogenesis and sperm function and perhaps contribute to male infertility as stated by56. Pertinent to this, The result was confirmed in the earlier study as stated by David et al. (2022) which showed a minimal reduction in testosterone levels among brick kiln workers20. Jahan et al. (2016) showed in the concerned research investigation that lower testosterone levels in brick kiln bakers and carriers when compared to a control group as stated by13. Tutkun et al. (2018) found that lead exposure induced damage to testicular Sertoli and Leydig cells and a drop in testosterone levels as stated by57.

Conclusion

The present study examined the effect of heavy metal exposure on the health of workers located at brick kilns in Layyah District. It was also shown in the present study that brick kiln workers had lower body weights and a variety of health concerns as well. It was examined that workers’ average lead and cadmium levels were found to be higher. Further, increasing heavy metal levels in workers’ blood altered blood parameters by increasing liver enzyme production, decreasing antioxidant enzyme levels, increasing oxidant production, decreasing HDL, increasing LDL, cholesterol, TG, decreasing bilirubin, protein, and testosterone production as well. The study’s findings are expected to provide valuable insights into the identification and management of reproductive and biochemical disorders. The findings may help in the Innovation of new diagnostic tools and treatment methods, which could greatly enhance patient outcomes. Further investigation in this area is required to confirm the study’s findings and determine their clinical implications. Further research should investigate the geochemical features of brick and brick kiln-producing materials as potential contributors to the heavy metal profile of blood samples collected from brick kiln workers. Due to the disregard of health concerns affecting brick kiln workers, more study is needed to address the public health and reproductive health challenges that these workers’ local communities face. This will facilitate the development of monitoring methods for emissions from brick kilns and ensure that medical assessments for labourers are available, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for these workers.

Data availability

Raw data will be available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Skinder, B., Pandit, A., Sheikh, A. & Ganai, B. J. J. P. E. C. Brick kilns: cause of atmospheric pollution. J. Pollut. Eff. Control 2, 3 (2014).

Parvez, M. A., Rana, I. A., Nawaz, A. & Arshad, H. S. H. The impact of brick kilns on environment and society: a bibliometric and thematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 48628–48653 (2023).

Shaikh, S. et al. Respiratory symptoms and illnesses among brick kiln workers: a cross sectional study from rural districts of Pakistan. BMC Public Health 12, 1–6 (2012).

Raza, A. & Ali, Z. Impact of air pollution generated by brick kilns on the pulmonary health of workers. J. Health Pollut. 11, 210906 (2021).

Rajarathnam, U. et al. Assessment of air pollutant emissions from brick kilns. Atmos. Environ. 98, 549–553 (2014).

Khan, M. W., Ali, Y., De Felice, F., Salman, A. & Petrillo, A. Impact of brick kilns industry on environment and human health in Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 678, 383–389 (2019).

Skinder, B. M., Pandit, A. K., Sheikh, A. & Ganai, B. Brick kilns: cause of atmospheric pollution. J. Pollut. Eff. Control 2, 3 (2014).

Bhanarkar, A., Gajghate, D. & Hasan, M. Assessment of air pollution from small scale industry. Environ. Monit. Assess. 80, 125–133 (2002).

Raut, A. Brick Kilns in Kathmandu Valley: Current status, environmental impacts and future options. Himal. J. Sci. 1, 59–61 (2003).

Sanjel, S., Thygerson, S. M., Khanal, S. N. & Joshi, S. K. Environmental and occupational pollutants and their effects on health among brick kiln workers. Open J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 6, 81–98 (2016).

Ismail, M. et al. Heavy Metals (Pb and Ni) Pollution as affected by the brick kilns emissions. Sarhad J. Agric. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2020/36.3.1001.1009 (2020).

Kaushik, R., Khaliq, F., Subramaneyaan, M. & Ahmed, R. Pulmonary dysfunctions, oxidative stress and DNA damage in brick kiln workers. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 31, 1083–1091 (2012).

Jahan, S., Falah, S., Ullah, H., Ullah, A. & Rauf, N. Antioxidant enzymes status and reproductive health of adult male workers exposed to brick kiln pollutants in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 12932–12940 (2016).

Mahurpawar, M. Effects of heavy metals on human health. Int. J. Res. Granthaalayah 530, 1–7 (2015).

Pariyar, S. K., Das, T. & Ferdous, T. Environment and health impact for brick kilns in Kathmandu valley. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2, 184–187 (2013).

Jahan, S. et al. Antioxidant enzymes status and reproductive health of adult male workers exposed to brick kiln pollutants in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 12932–12940 (2016).

David, M. et al. Biochemical and reproductive biomarker analysis to study the consequences of heavy metal burden on health profile of male brick kiln workers. Sci. Rep. 12, 7172 (2022).

Sikandar, M. A. et al. Economic analysis of wheat production in district Layyah Punjab, Pakistan. Remittances Rev. 9, 2840–2855 (2024).

Patil, D., Durgawale, D. & Gordhanbhal, S. A cross sectional study of socio–demographic and morbidity profile of brick kiln workers in rural area of Karad. Satara District. JMSRC 5, 15313–15321 (2017).

David, M. et al. Biochemical and reproductive biomarker analysis to study the consequences of heavy metal burden on health profile of male brick kiln workers. Sci. Rep. 12, 7172 (2022).

Ibrahim, A. J. the Determination and evaluation of trace elements in the blood of radiography workers using graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry. Anal. Methods Environ. Chem. J. 7, 76–85 (2024).

Afsar, T., Razak, S. & Almajwal, A. J. Effect of Acacia hydaspica R. Parker extract on lipid peroxidation, antioxidant status, liver function test and histopathology in doxorubicin treated rats. Lipids Health Dis. 18, 1–12 (2019).

Yahaya, T. et al. Cement dust exposure and risk of hyperglycemia and overweight among artisans and residents close to a cement factory in Sokoto, Nigeria. arXiv:2407.00420 (2024).

Afsar, T. et al. Acacia hydaspica R. Parker ethyl-acetate extract abrogates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by targeting ROS and inflammatory cytokines. Sci. Rep. 11, 17248 (2021).

Afsar, T. et al. Prevention of testicular damage by indole derivative MMINA via upregulated StAR and CatSper channels with coincident suppression of oxidative stress and inflammation: In silico and in vivo validation. Antioxidants 11, 2063 (2022).

Razak, S. et al. Molecular docking, pharmacokinetic studies, and in vivo pharmacological study of indole derivative 2-(5-methoxy-2-methyl-1H-indole-3-yl)-N′-[(E)-(3-nitrophenyl) methylidene] acetohydrazide as a promising chemoprotective agent against cisplatin induced organ damage. Sci. Rep. 11, 6245 (2021).

Rubio, C. P. & Cerón, J. J. Spectrophotometric assays for evaluation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in serum: General concepts and applications in dogs and humans. BMC Vet. Res. 17, 226 (2021).

Razak, S. et al. Sulindac acetohydrazide derivative attenuates against cisplatin induced organ damage by modulation of antioxidant and inflammatory signaling pathways. Sci. Rep. 12, 11749 (2022).

Sinharay, M., Chowdhury, P., Dasgupta, A. & Karmakar, A. Association of serum immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G antibody levels with different indicators of metabolic syndrome. Asian J. Med. Sci. 14, 101–107 (2023).

Rauf, A. et al. Prospects towards sustainability: A comparative study to evaluate the environmental performance of brick making kilns in Pakistan. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 94, 106746 (2022).

Liao, Z., Nie, J. & Sun, P. The impact of particulate matter (PM2. 5) on skin barrier revealed by transcriptome analysis: Focusing on cholesterol metabolism. Toxicol. Rep. 7, 1–9 (2020).

Sain, M. K. & Meena, M. Exploring the musculoskeletal problems and associated risk-factors among brick kiln workers. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 11, 395–410 (2018).

Joshi, S. K., Dahal, P., Poudel, A. & Sherpa, H. Work related injuries and musculoskeletal disorders among child workers in the brick kilns of Nepal. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Health 3, 2–7 (2013).

Saldaña-Villanueva, K. et al. Health effects of informal precarious workers in occupational environments with high exposure to pollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 76818–76828 (2023).

Berumen-Rodríguez, A. A. et al. Evaluation of respiratory function and biomarkers of exposure to mixtures of pollutants in brick-kilns workers from a marginalized urban area in Mexico. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 67833–67842 (2021).

Genchi, G., Sinicropi, M. S., Lauria, G., Carocci, A. & Catalano, A. The effects of cadmium toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 3782 (2020).

Kumar, K. & Singh, D. Toxicity and bioremediation of the lead: a critical review. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 34, 1–31 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Associations of diet quality and heavy metals with obesity in adults: a cross-sectional study from national health and nutrition examination survey (nhanes). Nutrients 14, 4038 (2022).

Ataro, Z., Geremew, A. & Urgessa, F. Occupational health risk of working in garages: comparative study on blood pressure and hematological parameters between garage workers and Haramaya University community, Harar, eastern Ethiopia. Risk Manag. Healthcare Policy 11, 35–44 (2018).

Rapisarda, V. et al. Blood pressure and occupational exposure to noise and lead (Pb) A cross-sectional study. Toxicol. Ind. Health 32, 1729–1736 (2016).

Kshirsagar, M. et al. Biochemical effects of lead exposure and toxicity on battery manufacturing workers of Western Maharashtra (India): with respect to liver and kidney function tests. Al Ameen J. Med. Sci. 8, 107–114 (2015).

Kargar-Shouroki, F., Mehri, H. & Sepahi-Zoeram, F. Biochemical and hematological effects of lead exposure in Iranian battery workers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 29, 661–667 (2023).

Kshirsagar, M. et al. Effects of lead on haem biosynthesis and haematological parameters in battery manufacturing workers of western Maharashtra, India. J. Pharm. Chem. Biol. Sci. 3, 477–487 (2016).

Dobrakowski, M. et al. Blood morphology and the levels of selected cytokines related to hematopoiesis in occupational short-term exposure to lead. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 305, 111–117 (2016).

Sun, Q. et al. Heavy metals induced mitochondrial dysfunction in animals: Molecular mechanism of toxicity. Toxicology 469, 153136 (2022).

Onah, C. E. et al. The effects of lead on some markers of liver and kidney functions of lead recycling factory workers are mediated through increased oxidative stress. Avicenna J. Med. Biochem. 11, 41–45 (2023).

Igharo, O. G. et al. Lipid profile and atherogenic indices in Nigerians occupationally exposed to e-waste: a cardiovascular risk assessment study. Maedica 15, 196 (2020).

Moitra, S., Brashier, B. B. & Sahu, S. Occupational cadmium exposure-associated oxidative stress and erythrocyte fragility among jewelry workers in India. Am. J. Ind. Med. 57, 1064–1072 (2014).

Goyal, T., Mitra, P., Singh, P., Sharma, P. & Sharma, S. Evaluation of oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines in occupationally cadmium exposed workers. Work 69, 67–73 (2021).

Mazumdar, I. & Goswami, K. Chronic exposure to lead: a cause of oxidative stress and altered liver function in plastic industry workers in Kolkata, India. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 29, 89–92 (2014).

Al Salhen, K. S. Assessment of oxidative stress, haematological, kidney and liver function parameters of Libyan cement factory workers. J. Am. Sci. 10, 58–65 (2014).

David, M. et al. Study of occupational exposure to brick kiln emissions on heavy metal burden, biochemical profile, cortisol level and reproductive health risks among female workers at Rawat, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 44073–44088 (2020).

Firoozichahak, A. et al. Effect of occupational exposure to lead on serum levels of lipid profile and liver enzymes: An occupational cohort study. Toxicol. Rep. 9, 269–275 (2022).

Haithem, F. & Louai, L. Y. R. Dietary Effect of Medicinal Plants against Heavy Metal Hepatotoxicity in Wistar Rats (Echahid chikh Larbi Tébessi University, 2024).

Ciarrocca, M., Capozzella, A., Tomei, F., Tomei, G. & Caciari, T. Exposure to cadmium in male urban and rural workers and effects on FSH, LH and testosterone. Chemosphere 90, 2077–2084 (2013).

Balachandar, R., Bagepally, B. S., Kalahasthi, R. & Haridoss, M. Blood lead levels and male reproductive hormones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Toxicology 443, 152574 (2020).

Tutkun, L., Iritas, S. B., Ilter, H., Gunduzoz, M. & Deniz, S. Effects of occupational lead exposure on testosterone secretion. Med. Sci. 7, 886–890 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting project number (ORF-2025-729), King Saud University, Riyadh Saudi Arabia for funding this project.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting project number (ORF-2025-729), King Saud University, Riyadh Saudi Arabia for funding this project. The funding body has no role in study design.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and experimentation done by KH, MKK, MD and SJ. data curation and writing—original draft preparation done by KH and MKK; writing—review and editing done by MD, SR, TA, FMH, and HS; visualization, supervision and funding acquisition done by SJ, TA and SR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and Approved by the Bio-Ethical Committee of the Department of Zoology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad and has assigned protocol #BEC-FBS-QAU2023-551. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants and/or their legal guardians. The study was carried out following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, K., Khan, M.K., David, M. et al. Detection of reproductive and hematobiochemical biomarkers to evaluate the impact of heavy metal exposure on brick kiln workers. Sci Rep 15, 19227 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04617-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04617-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Assessment of environmental pollutant exposure and cardiovascular risk in Mexican brick-making communities

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2026)

-

A Study on the Role of Oxidative Stress on the Sperm Quality of Individuals Occupationally Exposed to Air Pollution

Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry (2025)