Abstract

This study investigates the antimicrobial properties of honokiol (HNK), a naturally occurring polyphenol, when conjugated with short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate. We examined the effects of HNK-SCFA ester conjugates on Enterococcus faecalis, a gut bacterium that metabolizes levodopa, a drug used to manage Parkinson’s disease symptoms. Our findings indicate that HNK-SCFA-esters (e.g., HNK-acetate, HNK-propionate, HNK-butyrate, and HNK-hexanoate) inhibit E. faecalis growth in a dose-dependent manner, followed by a temporary recovery period during which levodopa remains intact and unmetabolized. Notably, HNK-SCFAs exhibit enhanced cellular permeability and are hydrolyzed within bacterial cells, releasing HNK and SCFAs. These results suggest that HNK-SCFAs may reversibly modulate the gut metabolism of levodopa to dopamine, potentially enhancing its therapeutic efficacy in treating Parkinson’s disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

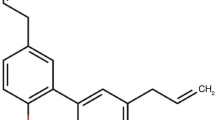

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor dysfunction and non-motor symptoms. Honokiol (HNK), a naturally occurring polyphenol derived from the bark of the Magnolia genus, has demonstrated neuroprotective effects in several PD mouse models1,2. To enhance its therapeutic potential, we investigated a novel strategy involving the synthesis of HNK conjugates with short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), generating a series of HNK-SCFA-esters (Figs. 1 and 2). These esters are designed to undergo hydrolysis by gut-derived esterases, thereby releasing both HNK and SCFAs in the gut.

Representative HNK-SCFA conjugates include honokiol acetic acid (HNK-Ac), propionic acid (HNK-PAc), butyric acid (HNK-BAc), and hexanoic acid (HNK-HAc), along with their bis-ester counterparts. The dual release of HNK and SCFAs offers the potential for synergistic neuroprotective effects. Although similar phenolic lipids have previously been explored as prodrugs of butyric acid for antibacterial applications3, and polyphenol-SCFA conjugates have been described4, their relevance to PD pathophysiology has not been established. Considering the unmet need for novel pharmacological approaches targeting both motor and non-motor PD symptoms, the development of HNK-SCFA esters represents a promising therapeutic strategy5.

Recent advances in microbiome research have highlighted the gut-brain axis as a key modulator of PD progression6,7,8,9,10. Patients with PD consistently exhibit decreased gut microbial diversity and diminished levels of SCFAs, particularly butyrate, due to decreased abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria11,12,13. This depletion correlates with the severity of both motor and non-motor symptoms, including depression in PD13. Moreover, sodium butyrate administration has been shown to restore striatal dopamine levels and improve motor performance in preclinical PD models14. Strategies aimed at augmenting gut-derived butyrate, through dietary supplementation, microbial modulation, or drug delivery, are of growing therapeutic interest in PD.

An additional microbiome-related challenge in PD is the compromised bioavailability of oral levodopa (L-dopa). Gut bacteria, particularly Enterococcus faecalis, metabolize L-dopa to dopamine via tyrosine decarboxylase in the gut, thereby reducing L-dopa’s systemic absorption and delivery to the brain15,16,17. Because dopamine produced in the gut cannot cross the blood–brain barrier, this microbial metabolism leads to decreased central dopaminergic activity. Importantly, deletion of the tyrosine decarboxylase gene in E. faecalis abolished L-dopa metabolism in the gut, underscoring its central role in this detrimental pathway15,16,17,18.

Although carbidopa, a peripheral aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor, is co-administered with L-dopa to prevent extracerebral metabolism, it does not inhibit bacterial tyrosine decarboxylases15,16,17. Consequently, gut microbial metabolism remains a barrier to therapeutic efficacy of L-dopa. In this study, we demonstrate that selected esterase-cleavable HNK-SCFA conjugates delay bacterial L-dopa metabolism and attenuate dopamine formation in a dose-dependent manner.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe polyphenol-based SCFA conjugates with esterase-labile and antimicrobial properties relevant to PD. These findings establish a mechanistic basis for a multifunctional therapy that integrates gut microbiome modulation, neuroprotection, and preservation of L-dopa bioavailability. This approach represents a significant step toward the development of gut-targeted pharmacological interventions for PD.

Results

Syntheses of HNK-SCFAs

HNK-SCFAs were synthesized by reacting HNK with the appropriate alkenoyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine in dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) (Fig. 2). The structures and purities of the products were confirmed by NMR analyses (Figs. S1 and S2).

Esterase-induced hydrolysis of HNK-SCFAs

HNK-SCFA-esters (HNK-Ac, HNK-PAc, HNK-BAc, HNK-HAc, and corresponding bis-esters) were hydrolyzed by esterase enzymes. Figure 3 illustrates the time-dependent formation of HNK and the corresponding SCFA. Notably, no hydrolysis was observed in vitro when HNK-SCFAs were incubated in formate buffer (pH = 3) at 37 °C (data not shown). Results showed that HNK-Ac and HNK-Bis-Ac underwent esterase-induced hydrolysis very rapidly (Fig. S3). Hydrolysis rates decreased with increasing chain length in the order: HNK-PAc < HNK-BAc < HNK-HAc.

Kinetics of esterase-induced hydrolysis of HNK-SCFA-mono and bis-esters. (A) Schemes showing the hydrolysis of HNK-SCFA-esters and the bis-esters. (B) Kinetics of esterase-induced hydrolysis of HNK-SCFAs. HNK-SCFA-esters (100 µM) were incubated in the presence of esterase (30 U/mL). (C) Kinetics of esterase-induced hydrolysis of HNK-SCFA-bis-esters. HNK-SCFA-bis-esters (100 µM) were incubated in the presence of esterase (30 U/mL).

Inhibition of E. faecalis proliferation by HNK-SCFAs

Unlike HNK (Fig. 4A), HNK-SCFAs bearing esterase-cleavable groups (e.g., HNK-BAc) induced a dose-dependent delay in E. faecalis proliferation (Fig. 4B, C, and D). After the time lag, bacterial growth resumed at a normal rate. In contrast, SCFAs alone inhibited E. faecalis proliferation without a time lag at millimolar levels (Fig. 4E–H).

Effect of SCFAs and HNK-SCFA-esters on E. faecalis proliferation. The effects of HNK-Ac (A), HNK-PAc (B), HNK-BAc (C), HNK-HAc (D), acetate (E), propionate (F), butyrate (G), and hexaonate (H) and on the proliferation of E. faecalis were monitored at OD 600 nm for 6 h. Data shown are the mean ± SD, n = 4.

Uptake and hydrolysis of HNK-SCFA conjugates by E. faecalis

Figure 5 illustrates the uptake and hydrolysis of HNK-Ac, HNK-PAc, HNK-BAc, and HNK-HAc by E. faecalis over 1 h. Intracellular concentrations increased with chain length (HNK-HAc = HNK-BAc > HNK-PAc > HNK-Ac) (Fig. S4). However, bacterial esterase-induced hydrolysis of HNK-SCFAs decreased with increasing chain length. Approximately 80% of HNK-Ac, 50% of HNK-PAc, 16% of HNK-BAc, and 10% of HNK-HAc were hydrolyzed to HNK. SCFAs (e.g., acetate, propionate, and butyrate) released from the hydrolysis of HNK-SCFA conjugates were not detectable using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)19, indicating the need for other mass spectrometry approaches such as GC-MS analyses.

Effect of HNK-SCFAs on L-dopa metabolism in E. faecalis cells

L-dopa is routinely used in combination with carbidopa in PD management. Therefore, we examined the effect of carbidopa (using the same L-dopa:carbidopa ratio as in clinical use) on L-dopa metabolism by E. faecalis treated with HNK-SCFAs. At clinically relevant ratios, carbidopa did not affect bacterial L-dopa metabolism, as it is a poor substrate for bacterial tyrosine decarboxylase15,16,17. Figure 6A–D shows that HNK-SCFAs dose-dependently decreased L-dopa degradation and dopamine formation by E. faecalis. Notably, both HNK-PAc and HNK-BAc inhibited dopamine formation more effectively than HNK-Ac. In contrast, HNK did not exhibit a similar pattern; with increasing doses, there was a total inhibition of E. faecalis proliferation (see Fig. 1 in Ref.20).

Effect of HNK-SCFA-esters on L-dopa degradation by E. faecalis. E. faecalis was treated with HNK-Ac (A), HNK-PAc (B), HNK-BAc (C), and HNK-HAc (D) as indicated, in the presence of 1 mM L-dopa and 0.22 mM of carbidopa. The effects of each analog (left), on the proliferation were monitored at OD600 for 6 h and culture media were collected at indicated time points (dashed lines) for L-dopa and dopamine measurements. HPLC traces of representative samples and standards are shown in the middle left panel. The effects on L-dopa consumption and dopamine formation are shown respectively. *, P < 0.05 vs. control group at each collection time point. Data shown are the mean ± SD, n = 4.

Effect of HNK-SCFA-esters on membrane potential

As shown in Fig. 7A, HNK-PAc, HNK-BAc, and HNK-HAc induced a dose-dependent increase in E. faecalis membrane potential, with HNK-BAc exhibiting the strongest effect among the HNK-SCFA conjugates. In contrast, acetate, propionate, and butyrate did not affect membrane potential across a range of concentrations (Fig. 7B). These findings are consistent with the observed enhanced uptake of HNK-SCFA-esters in the E. faecalis system (Fig. 6). The paradoxical effects of SCFAs in bacterial versus mammalian cells are further discussed in the “Discussion” Section.

Effect of HNK-SCFA-esters on E. faecalis membrane potential. E. faecalis was treated with HNK, HNK-Ac, HNK-PAc, HNK-BAc, and HNK-HAc (A) and acetate, propionate, butyrate, and hexanoate (B) as indicated for 1 h. The effects on the membrane potential were measured by TMRM dye, the fluorescence indicator to determine the percentage change in TMRM fluorescence intensity between the control and treatments groups. The lower levels of TMRM fluorescence resulting from treatment reflect the depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential. **, P < 0.01 vs. control group at each collection time point. Data shown are the mean ± SD, n = 4.

Effects of HNK-SCFAs on ATP levels in E. faecalis

Intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was measured in E. faecalis cells exposed to HNK-SCFAs and SCFAs. As shown, the effects of HNK-SCFAs on ATP formation varied (Fig. 8). Initially, HNK-SCFAs enhanced ATP levels followed by a decrease. SCFAs alone (Fig. S5) increased ATP levels in E. faecalis cells at millimolar concentrations.

HNK-BAc induced a dose- and time-dependent increase in ATP in the E. faecalis system. In HNK-BAc treated E. faecalis, ATP levels were initially higher in the presence of HNK-SCFAs, likely due to decreased ATP utilization under suppressed proliferation. After a dose-dependent time lag, the proliferation rates of E. faecalis increased over time in the presence of HNK-SCFAs. Accordingly, ATP levels began to decrease due to utilization (Fig. 8).

In the presence of SCFAs alone, ATP levels increased (Fig. S5). This increase is likely due to the utilization of SCFAs, such as acetate, by E. faecalis to generate more ATP. However, it is important to note that high millimolar concentrations of SCFAs were used in this experiment.

Antimicrobial effects of HNK-SCFAs

Antimicrobial activity was assessed using a standard micro-dilution assay to determine minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC), the lowest concentration that completely inhibits bacterial growth during overnight incubation at 37 °C21. HNK-Ac had a MIC of 180 µM when tested against E. faecalis. None of the other HNK derivatives exhibited antimicrobial activity at the highest concentration tested (180 µM). This is consistent with results from proliferation assays indicating that these compounds inhibit bacterial growth for periods of up to 6 h, after which proliferation recovers.

Cytotoxicity of HNK-SCFAs

Cytotoxicity was monitored in real time by SYTOX Green staining. The SYTOX measurements showed that HNK-SCFAs were non-cytotoxic at concentrations inhibiting > 90% proliferation of E. faecalis (Fig. S6). In contrast, the antibiotic ampicillin was cytotoxic at concentrations inhibiting E. faecalis proliferation20.

Calculated values of the octanol/water partition coefficients

The hydrophobicity of HNK-SCFAs was assessed by calculating the log P partition coefficients22,23. The calculated log P values for HNK, HNK-Ac, HNK-PAc, HNK-BAc, and HNK-HAc are 5.2, 5.1, 5.9, 6.3, and 7.2, respectively (Table S1). The log P values of HNK-ester analogs (mono and bis-esters) were assessed using a QSAR (quantitative structure–activity relationship) analysis and rational drug design as a measure of molecular hydrophobicity (Table S1). This method also uses a consensus model built using the ChemAxon software (San Diego, CA)22,23.

Discussion

This study has significant scientific impact as it reveals a novel therapeutic potential to mitigate the gut metabolism of L-dopa to dopamine using nontoxic SCFA conjugates of HNK, a naturally occurring polyphenol. Both HNK and SCFAs have been shown to be nontoxic and neuroprotective. HNK is a commercially available nutritional supplement that is also widely used as a drug to induce sleep. SCFAs are key players in the interplay between diet, microbiota, and health24,25. SCFAs, including acetate (two carbons), propionate (three carbons), and butyrate (four carbons), are produced through anerobic fermentation of dietary fibers by the colonic microbiome26. The relative amounts of SCFA released in the gut depend on the type and amount of ingested fiber.

Propionate, a major microbial fermentation-induced metabolite in the human gut, has been shown to be neuroprotective in PD27,28,29,30. Additionally, butyrate-generating bacteria have been associated with neuroprotection in PD31. Increasing gut butyrate through prebiotic butyrogenic fibers has been proposed as a potential therapy32. The bioavailability of L-dopa in the brain decreases in patients with PD due to the increased metabolism of L-dopa to dopamine by gut bacteria, specifically E. faecalis15,16,17. The abundance of E. faecalis in human gut microbiota samples strongly correlates with L-dopa metabolism15, and patients with PD have varying levels of these bacteria. Thus, decreasing bacterial metabolism is a promising therapeutic approach to enhance the bioavailability of L-dopa in the brain. Previously, we showed that HNK, conjugated to a triphenylphosphonium moiety, mitigated the metabolism of L-dopa—alone or combined with carbidopa—to dopamine. Mito-ortho-HNK suppressed the growth of E. faecalis, decreased dopamine levels in the gut, and increased dopamine levels in the brain. Here, we show that mitigating the gut bacterial metabolism of L-dopa using a hybrid molecule consisting of a naturally occurring molecule and an endogenous gut metabolite could enhance the efficacy of L-dopa.

Results indicate that HNK-SCFAs enhanced the membrane potential of E. faecalis, resulting in hyperpolarization (Fig. 6A). Hyperpolarization results when the membrane potential becomes more negative, whereas depolarization occurs when the membrane potential becomes less negative or more positive. However, HNK and SCFAs alone did not affect the membrane potentials (Fig. 6B). The increase in membrane potential followed the order: HNK-BAc > HNK-PAc > HNK-HAc > HNK-Ac (Fig. 6A). This finding contradicts previous studies33. Under physiological pH values, the membrane potential of anaerobic gut commensal bacteria remained unchanged but slightly decreased at lower pH levels. In a model of colonic SCFA absorption using basolateral membrane vesicles from rat distal colonic mucosa, butyrate uptake was significantly higher at acidic extravesicular pH = 5.5 than at pH = 7.534. Butyrate was reported to cause a reversible hyperpolarization in neurons due to increased intracellular calcium ions35. Propionate induced hyperpolarization in gallbladder epithelial cells36,37. Acetate-induced hyperpolarization was attributed differences in calcium permeability38.

HNK-SCFAs, as a novel class of prodrugs, have the potential to release two neuroprotective molecules: HNK and SCFAs like butyrate. Both molecules have been shown to inhibit neuroinflammation and reverse neurodegeneration1,39,40,41. HNK activates mitochondrial sirtuin-3 (Sirt-3), which induces antitumor and anti-inflammatory effects. Sirt-3 is implicated as a potential target for PD42.

HNK promotes mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics through a Sirt-3-depenndent mechanism involving the AMPK-PGC-1alpha signaling pathway. Additionally, HNK activates the NAD+-consuming enzyme Sirt-3 to prevent neuron death and improve motor performance in a rat model of PD43,44,45,46.

HNK also decreases alpha-synuclein mRNA levels, potentially decreasing alpha-synuclein aggregation and the onset of neurological disorders collectively known as “synucleinopathies” including PD47. This study revealed a novel therapeutic target for modulating alpha-synuclein expression. Furthermore, propionate supplementation has been shown to reverse alpha-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans48,49,50. Enhancing SCFAs, such as propionate, in the gut through pharmacotherapy was shown to be beneficial in protecting against alpha-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration50. Therefore, HNK-SCFAs may provide a synergistic therapeutic effect in combating synucleinopathy. The therapeutic signaling of SCFA receptors has been proposed as a treatment for neuroinflammatory disorders51.

Although butyrate has been used as a nutritional supplement, its pungent and unfavorable odor has limited its widespread applications (Fig. S7). To overcome this problem, modified forms of butyrate were synthesized as prodrugs that release butyric acid through enzymatic hydrolysis (structures shown in Fig. S7). Proper administration of these drugs could offer advantages over probiotics. One such drug is arginine butyrate, an ester formed by combining arginine and butyrate, which is hydrolyzed to release arginine and butyrate in vivo52. Administering low doses of arginine butyrate restored membrane integrity and improved neuromuscular abnormalities in dystrophic mouse models52. These beneficial effects are attributed to HDAC (histone deacetylase) inhibition by butyrate and the inhibitory effects of nitric oxide synthase/arginine on intracellular calcium activity. Another prodrug, tributyrin (propane-1,2,3-triyl tributanoate), is a triglyceride derived from glycerol and three molecules of butyric acid. Present in butter and used in margarine, tributyrin serves as a postbiotic microbiome supplement. It is rapidly absorbed as a prodrug that is hydrolyzed by the lipase enzyme to butyric acid, inducing apoptosis and inhibiting prostate cancer cells53, and modulating gene transcription through HDAC inhibition54. Phenylalanine-butyramide, a novel butyrate derivative, has demonstrated protective effects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity55. It is also considered as a postbiotic that improves gut health by releasing butyrate. However, the mechanism of butyrate formation remains unclear. Additionally, amino acid-conjugated butyrate (e.g., serine-conjugated butyrate) has been used as a prodrug in autoimmune arthritis and neuroinflammation in preclinical mouse models56. Butyryl-L-carnitine, a butyrate ester of carnitine, is proposed as a prodrug for delivering carnitine and butyrate in the gut and preventing inflammation57.

Research suggests that L-dopa responsiveness in patients with PD may be associated with the abundance of the tyrosine decarboxylase gene in the gut18. Although this gene is found in bacteria like Lactobacillus brevis in humans, this gene is primarily associated with E. faecalis. Individuals with PD reportedly have decreased levels of SCFAs in their gut microbiome58. Additionally, bacteria that metabolize L-dopa in the small intestine have been detected in the feces of people with PD59. The metabolism of L-dopa by gut microbes and amino acid carboxylases in peripheral tissues contributes to the reduced availability of L-dopa in the brain.

A combination of L-dopa and carbidopa is the preferred treatment for managing PD symptoms. Although carbidopa does not prevent gut metabolism of L-dopa, it does inhibit peripheral metabolism of L-dopa by acting as a substrate inhibitor of peripheral amino carboxylases15. Interestingly, HNK-SCFAs may enhance the efficacy of L-dopa/carbidopa therapy by directly inhibiting both gut bacteria metabolism and peripheral metabolism of L-dopa60. Thus, a potential clinical implication of this work is the development of adjunctive pharmacomicrobiome therapy targeting the gut–brain axis60.

This study has some limitations. Notably, it did not demonstrate the enhanced therapeutic efficacy of L-dopa/carbidopa/HNK-SCFAs in a PD-relevant genetic model, such as the MitoPark mouse61. Additionally, the study did not investigate the effects of HNK-SCFAs on L-dopa-induced dyskinesia in a mouse model62.

A genetically engineered mouse model, the MitoPark mouse, recapitulates many of the phenotypic features (mitochondrial dysfunction, microglial activation, dopaminergic degeneration, dopamine deficiency, and progressive neuronal deficits and protein occlusion) of PD. We propose that the benefits of treating human PD with L-dopa can be potentiated by the use of adjunctive treatments utilizing HNK-SCFAs that inhibit the breakdown of L-dopa to dopamine in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby enhancing L-dopa conversion to dopamine in the brain. The MitoPark transgenic mouse model is particularly relevant, as it replicates key PD features including gastrointestinal dysfunction associated with PD63. In addition, it will be important to determine if the beneficial effects of HNK-SCFAs observed in the current study are maintained with repeated treatments over an extended period of time. Collaboratively, we have previously published the neuroprotective effects of mitochondria-targeted drugs in the MitoPark mouse64,65. Studies using MitoPark mice are not feasible at this time; however, future collaborative research will investigate these aspects.

Methods

Bacterial strain and culture conditions

E. faecalis (Cat# OG1RF) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). E. faecalis was cultured and grown overnight in TSB (tryptic soy broth), diluted 1:200 into fresh TSB and then grown at 37 °C in flasks on a rotating shaker at 250 rpm to reach the exponential growth phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.2–0.5) before use in the in vitro assays.

Synthesis and purification of HNK-SCFA conjugates

All reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. HNK-SCFA esters were synthesized by acylation of HNK with the corresponding alkenoyl chlorides in CH₂Cl₂ in the presence of triethylamine. Reaction progress was monitored by thin layer chromatography using silica gel Merck 60F254. Crude materials were purified by flash chromatography on Merck Silica gel 60 (0.040–0.063 mm). 1H NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker DPX AVANCE 400 spectrometer equipped with a quattro nucleus probe. 1H NMR and 13C were taken in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) using CDCl3 and tetramethyl silane as internal reference respectively. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm and J values in Hertz (see Supplemental Materials section).

Measurement of bacterial cell proliferation

For all proliferation assays, cells were diluted to the final OD600 of 0.1 with indicated treatments in a 96-well plate. Cell proliferation, which was represented as absorbance at 600 nm, was acquired in real time every 3 min for 6 h using a plate reader (BMG Labtech, Inc., Ortenberg, Germany) equipped with an atmosphere controller set at 37 °C, 100% air.

Measurement of bacterial membrane potential

Membrane potential was measured using the fluorescence dye tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM)66,67,68. Briefly, bacteria in the exponential growth phase (OD600 of 0.4) were treated with test compounds as previously indicated for the MTDs or commonly used antibiotics in a black, clear-bottom 96-well plate; then, an aliquot of TMRM was added at a final concentration of 50 nM for 20 min15,66,68,69. After incubation with TMRM, the plate was centrifuged twice at 2500 g for 5 min and washed with phosphate buffered saline. Fluorescence was monitored at an excitation of 544 nm and emission of 590 nm using a plate reader (BMG Labtech, Inc., Cary, NC). Data were collected as the mean fluorescent intensity and were normalized to the total OD600 as the total bacteria number. The effects on membrane potential were compared for potential correlation with the MIC and minimum bactericidal concentration values.

Uptake and intracellular hydrolysis of HNK-SCFAs

E. faecalis cells in the exponential growth phase (OD600 = 0.3–0.5) were diluted to the final OD600 of 0.1 at 20 mL volume, then treated with HNK or HNK-SCFAs as indicated for 1 h. Cell pallets were collected by centrifugation at 2,500 g × 5 min at 4 °C and stored at − 80 °C before extraction was performed. The cell pallet was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (100 µL) and taken for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis.

HNK-SCFAs and HNK formed from hydrolysis were separated and monitored by HPLC using an Agilent 1200 apparatus equipped with ultraviolet-visible absorption. Typically, 4 µL of a sample was injected on a Phenomenex reverse phase column (Kinetex 2.6 µ, 100 mm × 4.6 mm). The absorption traces were collected at 254 nm. The compounds were separated by a linear increase in acetonitrile phase concentration from 10 to 100% over 14 min and until 17 min at 100% acetonitrile containing 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid. The flow rate used was 1.3 mL/min.

Measurement of intracellular ATP

Intracellular ATP was quantified using a luciferase-based ATP determination kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, Cat# FLLAA). Following cell lysis, a luciferase/luciferin agent (Cat# FLAAM) was added to the cell lysates. After swirling, luminescence was measured using a luminometer, and results were normalized to total cell numbers, which was represented as absorbance at 600 nm (OD600nm).

Cytotoxicity measurements

Cytotoxicity was evaluated using the SYTOX Green (Invitrogen, Cat# S7020)20. The SYTOX method labels the nuclei of dead cells, yielding green fluorescence. Fluorescence (Ex: 485 nm, Em: 535 nm) from the dead cells in the 96-well plate were recorded every 5 min for 3 h using a plate reader (BMG Labtech, Inc.) equipped with an atmosphere controller set at 37 °C.

E. faecalis cells in the exponential growth phase (OD600 = 0.4) were treated with HNK-SCFAs in a black, clear-bottom 96-well plate for 3 h, and dead cells were monitored in the presence of 200 nM SYTOX Green. Cell lysis reagent (B-PER complete bacterial protein extraction reagent, Thermo Scientific, Cat# 89821) was used as a positive control.

L-dopa metabolism and LC-MS analysis

E. faecalis cells in the exponential growth phase (OD600 of ~ 0.4) were diluted to a final OD600 of 0.1 and treated with L-dopa (1 mM) alone or in combination with carbidopa (0.22 mM) as previously described20. At the indicated time points (1–6 h), samples (1 mL of media) were collected by centrifugation at 2,500 g × 5 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was lyophilized. The dry residue consisting of L-dopa and metabolites was resuspended in ice-cold methanol (100 µL) and analyzed by LC-MS using an Agilent 1200 apparatus equipped with ultraviolet-visible absorption and a mass spectrometry detector (single quadrupole). Typically, 2 µL of a sample was injected on an Agilent Poroshell column (120 HILIC-Z, PEEK, 100 mm × 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm, 25 °C), with absorbance monitored at 280 nm.

Esterase-mediated hydrolysis of HNK-SCFAs

HNK-SCFA-esters (1 mM) solutions were prepared in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4). Then, HNK-SCFA-esters (100 µM) were incubated with esterase (30 U/mL) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). A 4 µL mixture was injected into HPLC to monitor the cleavage of the esters with the release of HNK and the corresponding SCFAs.

HPLC analyses were performed using an Agilent 1200 system equipped with absorption detectors. The samples (5 µL) were injected into a reverse phase column (Phenomenex, Kinetex C18, 100 mm × 4.6 mm, 2.6 μm) equilibrated with 10% (v/v) MeCN, 90% (v/v) water containing 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid.

HNK esters derivatives were eluted by increasing the content of MeCN (v/v) from 20 to 100% over 14 min and until 17 min at 100% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.3 mL/min. The absorption used to monitor the ester cleavages was 254 nm.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), as indicated. Comparisons between treatment and control groups were performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Sample sizes (n) are indicated in figure legends.

Data availability

This study did not generate/analyze any computational datasets/code or publicly archived datasets. All data are provided within the manuscript. Requests for information, resources, and reagents are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chen, H. H. et al. Therapeutic effects of Honokiol on motor impairment in Hemiparkinsonian mice are associated with reversing neurodegeneration and targeting PPARγ regulation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 108, 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.095 (2018).

Chen, H. H., Chang, P. C., Chen, C. & Chan, M. H. Protective and therapeutic activity of Honokiol in reversing motor deficits and neuronal degeneration in the mouse model of parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol. Rep. 70, 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharep.2018.01.003 (2018).

Kaki, S. S., Kunduru, K. R., Kanjilal, S. & Narayana Prasad, R. B. Synthesis and characterization of a novel phenolic lipid for use as potential lipophilic antioxidant and as a prodrug of Butyric acid. J. Oleo Sci. 64, 845–852. https://doi.org/10.5650/jos.ess15035 (2015).

Shih, M. K. et al. Separation and identification of resveratrol butyrate ester complexes and their bioactivity in HepG2 cell models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413539 (2021).

Tizabi, Y., Getachew, B. & Aschner, M. Novel pharmacotherapies in Parkinson’s disease. Neurotox. Res. 39, 1381–1390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12640-021-00375-5 (2021).

Fan, H. et al. Which one is the superior target? A comparison and pooled analysis between posterior subthalamic area and ventral intermediate nucleus deep brain stimulation for essential tremor. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 28, 1380–1392. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13878 (2022).

Liu, J., Xu, F., Nie, Z. & Shao, L. Gut microbiota Approach-A new strategy to treat Parkinson’s disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 570658. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.570658 (2020).

Sampson, T. R. et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell 167, 1469–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.018 (2016).

Guo, T. & Chen, L. Gut microbiota and inflammation in Parkinson’s disease: Pathogenetic and therapeutic insights. Eur. J. Inflamm. 20, 1721727X221083763. https://doi.org/10.1177/1721727x221083763 (2022).

Metzdorf, J. & Tönges, L. Short-chain fatty acids in the context of Parkinson’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 16, 2015–2016. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.308089 (2021).

Unger, M. M. et al. Short chain fatty acids and gut microbiota differ between patients with Parkinson’s disease and age-matched controls. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 32, 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.08.019 (2016).

Wu, G. et al. Serum short-chain fatty acids and its correlation with motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease patients. BMC Neurol. 22, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02544-7 (2022).

Xie, A. et al. Bacterial butyrate in Parkinson’s disease is linked to epigenetic changes and depressive symptoms. Mov. Disord. 37, 1644–1653. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.29128 (2022).

Guo, T. T. et al. Neuroprotective effects of sodium butyrate by restoring gut microbiota and inhibiting TLR4 signaling in mice with MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040930 (2023).

Maini Rekdal, V., Bess, E. N., Bisanz, J. E., Turnbaugh, P. J. & Balskus, E. P. Discovery and Inhibition of an interspecies gut bacterial pathway for Levodopa metabolism. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau6323 (2019).

Jameson, K. G. & Hsiao, E. Y. A novel pathway for microbial metabolism of Levodopa. Nat. Med. 25, 1195–1197. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0544-x (2019).

van Kessel, S. P. et al. Gut bacterial tyrosine decarboxylases restrict levels of Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 10, 310. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08294-y (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between microbial tyrosine decarboxylase gene and Levodopa responsiveness in patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology 99, e2443–e2453. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000201204 (2022).

Chalova, P. et al. Determination of short-chain fatty acids as putative biomarkers of cancer diseases by modern analytical strategies and tools: A review. Front. Oncol. 13, 1110235. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1110235 (2023).

Cheng, G., Hardy, M., Hillard, C. J., Feix, J. B. & Kalyanaraman, B. Mitigating gut microbial degradation of Levodopa and enhancing brain dopamine: Implications in Parkinson’s disease. Commun. Biol. 7, 668. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06330-2 (2024).

Weinstein, M. P. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically (Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, 2018).

Viswanadhan, V. N., Ghose, A. K., Revankar, G. R. & Robins, R. K. Atomic physicochemical parameters for three dimensional structure directed quantitative structure-activity relationships. 4. Additional parameters for hydrophobic and dispersive interactions and their application for an automated superposition of certain naturally occurring nucleoside antibiotics. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 29, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci00063a006 (1989).

Klopman, G., Li, J. Y., Wang, S. & Dimayuga, M. Computer automated log P calculations based on an extended group contribution approach. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 34, 752–781. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci00020a009 (1994).

Kalyanaraman, B., Cheng, G. & Hardy, M. Gut microbiome, short-chain fatty acids, alpha-synuclein, neuroinflammation, and ROS/RNS: Relevance to parkinson’s disease and therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 71, 103092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2024.103092 (2024).

van der Hee, B. & Wells, J. M. Microbial regulation of host physiology by Short-chain fatty acids. Trends Microbiol. 29, 700–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2021.02.001 (2021).

Koh, A., De Vadder, F., Kovatcheva-Datchary, P. & Bäckhed, F. From dietary Fiber to host physiology: Short-Chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 165, 1332–1345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041 (2016).

Hosseini, E., Grootaert, C., Verstraete, W. & Van de Wiele, T. Propionate as a health-promoting microbial metabolite in the human gut. Nutr. Rev. 69, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00388.x (2011).

Morrison, D. J. & Preston, T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes 7, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082 (2016).

den Besten, G. et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 54, 2325–2340. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R036012 (2013).

Gomes, S. D. et al. The role of diet related Short-Chain fatty acids in colorectal Cancer metabolism and survival: Prevention and therapeutic implications. Curr. Med. Chem. 27, 4087–4108. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867325666180530102050 (2020).

Tan, A. H., Hor, J. W., Chong, C. W. & Lim, S. Y. Probiotics for parkinson’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. JGH Open 5, 414–419. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgh3.12450 (2021).

Cantu-Jungles, T. M., Rasmussen, H. E. & Hamaker, B. R. Potential of prebiotic butyrogenic fibers in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 10, 663. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00663 (2019).

Chang, K. C., Nagarajan, N. & Gan, Y. H. Short-chain fatty acids of various lengths differentially inhibit Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacteriaceae species. mSphere 9, e0078123. https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00781-23 (2024).

Reynolds, D. A., Rajendran, V. M. & Binder, H. J. Bicarbonate-stimulated [14C]butyrate uptake in basolateral membrane vesicles of rat distal colon. Gastroenterology 105, 725–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(93)90889-k (1993).

Haschke, G., Schafer, H. & Diener, M. Effect of butyrate on membrane potential, ionic currents and intracellular Ca2+ concentration in cultured rat myenteric neurones. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 14, 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00312.x (2002).

Petersen, K. U. & Reuss, L. Electrophysiological effects of propionate and bicarbonate on gallbladder epithelium. Am. J. Physiol. 248, C58–C69. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.1985.248.1.C58 (1985).

Purmal, C. et al. Propionate stimulates pyruvate oxidation in the presence of acetate. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 307, H1134–H1141. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00407.2014 (2014).

Preston, R. R. & Van Houten, J. L. Chemoreception in Paramecium tetraurelia: Acetate and folate-induced membrane hyperpolarization. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 160, 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00615086 (1987).

Woodbury, A., Yu, S. P., Wei, L. & García, P. Neuro-modulating effects of honokiol: A review. Front. Neurol. 4, 130. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2013.00130 (2013).

Matt, S. M. et al. Butyrate and dietary soluble Fiber improve neuroinflammation associated with aging in mice. Front. Immunol. 9, 1832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01832 (2018).

Chakraborty, P., Gamage, H. & Laird, A. S. Butyrate as a potential therapeutic agent for neurodegenerative disorders. Neurochem. Int. 176, 105745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2024.105745 (2024).

Zhou, Z. D. & Tan, E. K. Oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent mitochondrial deacetylase sirtuin-3 as a potential therapeutic target of Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 62, 101107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2020.101107 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Small molecule natural compound agonist of SIRT3 as a therapeutic target for the treatment of intervertebral disc degeneration. Exp. Mol. Med. 50, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0173-3 (2018).

Pillai, V. B. et al. Honokiol blocks and reverses cardiac hypertrophy in mice by activating mitochondrial Sirt3. Nat. Commun. 6, 6656. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7656 (2015).

Tang, P. et al. Honokiol alleviates the degeneration of intervertebral disc via suppressing the activation of TXNIP-NLRP3 inflammasome signal pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 120, 368–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.04.008 (2018).

Xiao, B., Kuruvilla, J. & Tan, E. K. Mitophagy and reactive oxygen species interplay in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 8, 135. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-022-00402-y (2022).

Fagen, S. J. et al. Honokiol decreases alpha-synuclein mRNA levels and reveals novel targets for modulating alpha-synuclein expression. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1179086. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1179086 (2023).

Chang, S. C. & Lee, V. H. Influence of chain length on the in vitro hydrolysis of model ester prodrugs by ocular esterases. Curr. Eye Res. 2, 651–656. https://doi.org/10.3109/02713688209019993 (1982).

Ohkawa, I., Shiga, S. & Kageyama, M. An esterase on the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for the hydrolysis of long chain acyl esters. J. Biochem. 86, 643–656. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132568 (1979).

Wang, C., Yang, M., Liu, D. & Zheng, C. Metabolic rescue of α-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration through propionate supplementation and intestine-neuron signaling in C. elegans. Cell. Rep. 43, 113865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.113865 (2024).

Prado, C. & Pacheco, R. Targeting short-chain fatty acids receptors signalling for neurological disorders treatment. Explor. Neuroprotective Ther. 4, 100–107. https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2024.00073 (2024).

Vianello, S. et al. Arginine butyrate: A therapeutic candidate for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. FASEB J. 27, 2256–2269. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.12-215723 (2013).

Maier, S. et al. Tributyrin induces differentiation, growth arrest and apoptosis in androgen-sensitive and androgen-resistant human prostate cancer cell lines. Int. J. Cancer 88, 245–251 (2000).

Rocchi, P. et al. p21Waf1/Cip1 is a common target induced by short-chain fatty acid HDAC inhibitors (valproic acid, tributyrin and sodium butyrate) in neuroblastoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 13, 1139–1144 (2005).

Russo, M. et al. The novel butyrate derivative phenylalanine-butyramide protects from doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 21, 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1439 (2019).

Cao, S. et al. A serine-conjugated butyrate prodrug with high oral bioavailability suppresses autoimmune arthritis and neuroinflammation in mice. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 8, 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-024-01190-x (2024).

Srinivas, S. R., Prasad, P. D., Umapathy, N. S., Ganapathy, V. & Shekhawat, P. S. Transport of butyryl-L-carnitine, a potential prodrug, via the carnitine transporter OCTN2 and the amino acid transporter ATB0,+. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 293, G1046–G1053. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00233.2007 (2007).

Brown, E. G. & Goldman, S. M. Modulation of the Microbiome in parkinson’s disease: Diet, drug, stool transplant, and beyond. Neurotherapeutics 17, 1406–1417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-020-00942-2 (2020).

van Kessel, S. P. & El Aidy, S. Contributions of gut bacteria and diet to drug pharmacokinetics in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 10, 1087. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01087 (2019).

Menozzi, E. & Schapira, A. H. V. The gut microbiota in Parkinson disease: Interactions with drugs and potential for therapeutic applications. CNS Drugs 38, 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-024-01073-4 (2024).

Ekstrand, M. I. & Galter, D. The mitopark Mouse—an animal model of Parkinson’s disease with impaired respiratory chain function in dopamine neurons. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15(Suppl 3), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1353-8020(09)70811-9 (2009).

Shan, L. et al. L-Dopa induced dyskinesias in Parkinsonian mice: Disease severity or L-Dopa history. Brain Res. 1618, 261–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2015.06.005 (2015).

Ghaisas, S. et al. MitoPark Transgenic mouse model recapitulates the Gastrointestinal dysfunction and gut-microbiome changes of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicology 75, 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2019.09.004 (2019).

Langley, M. et al. Mito-apocynin prevents mitochondrial dysfunction, microglial activation, oxidative damage, and progressive neurodegeneration in mitopark Transgenic mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 27, 1048–1066. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2016.6905 (2017).

Ay, M. et al. Mito-metformin protects against mitochondrial dysfunction and dopaminergic neuronal degeneration by activating upstream PKD1 signaling in cell culture and mitopark animal models of parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 18, 1356703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2024.1356703 (2024).

Kumari, S. et al. Antibacterial activity of new structural class of semisynthetic molecule, triphenyl-phosphonium conjugated diarylheptanoid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 143, 140–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.08.003 (2019).

Wu, M. & Hancock, R. E. Interaction of the Cyclic antimicrobial cationic peptide bactenecin with the outer and cytoplasmic membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.274.1.29 (1999).

Friedrich, C. L., Moyles, D., Beveridge, T. J. & Hancock, R. E. Antibacterial action of structurally diverse cationic peptides on gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 2086–2092. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.44.8.2086-2092.2000 (2000).

Benarroch, J. M. & Asally, M. The microbiologist’s guide to membrane potential dynamics. Trends Microbiol. 28, 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2019.12.008 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01CA208648 (BK), the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Federal Award RS 20182223-00 (BK), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21NS137244 (JBF), a program project formation grant from the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment (BK, JBF), the Harry R. and Angeline E. Quadracci Professor in Parkinson’s Research Endowment (BK), and International Research Project SuperO2 from CNRS, France (MH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Thanks to Lydia Washechek for preparing and proofreading the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C., M.H., J.F., and B.K.; methodology, G.C., M.H., J.F., and B.K.; software, G.C. and M.H.; validation, G.C., M.H., J.F., and B.K.; formal analysis, G.C., M.H., J.F., and B.K.; investigation, G.C., M.H., and J.F.; resources, M.H., J.F., and B.K.; data curation, G.C. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.; writing—review and editing, G.C., M.H., J.F., and B.K.; visualization, G.C. and M.H.; supervision, J.F. and B.K. ; project administration, M.H., J.F., and B.K.; funding acquisition, M.H., J.F., and B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Balaraman Kalyanaraman and Micael Hardy are inventors of US Patent No. 10,836,782/European Patent No. 3307254, “Mito-honokiol compounds and methods of synthesis and use thereof.” The other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, G., Hardy, M., Feix, J.B. et al. Inhibition of levodopa metabolism to dopamine by honokiol short-chain fatty acid derivatives may enhance therapeutic efficacy in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep 15, 20004 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05072-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05072-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Lifestyle medicine in Parkinson’s disease

Journal of Neural Transmission (2025)