Abstract

Atherosclerosis (AS), driven by vascular endothelial dysfunction and poses a global health threat. This study compared the therapeutic effects of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) on vascular endothelial function in early-stage AS mice, specifically investigating PCSK9 modulation and the TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N pathway. ApoE−/− mice (n = 6/group) fed a high-fat diet for 12 weeks were randomized into sedentary (AS-S), HIIT (AS-HIIT), and MICT (AS-MICT) groups, with wild-type mice as control. Training lasted 12 weeks. Outcomes included body weight, lipid profiles (TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C), oxidative stress markers (T-SOD, GSH-Px, MDA), vascular function (eNOS expression, ACh-induced vasorelaxation), and TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N pathway activity. Both HIIT and MICT reduced body weight (p < 0.05) and improved lipid profile. Exercise groups showed reduced oxidative stress and inflammation pathways (p < 0.05). HIIT and MICT ameliorate early AS by reducing PCSK9 and oxidative/inflammatory pathway levels (p < 0.05), but HIIT demonstrates superior efficacy in improving endothelial function and pathway activation. These findings show HIIT and MICT mitigate endothelial dysfunction in early atherosclerotic mice via PCSK9 inhibition and advocate for HIIT as a prioritized strategy in early AS management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The instability of atherosclerotic plaques can lead to thrombus formation, which may result in myocardial infarction or stroke. These plaques are primarily composed of lipids, fibrous tissue, and calcium, and they are prone to secondary complications such as calcification, ulceration, thrombus formation, and intraplaque hemorrhage1,2. Effectively halting AS progression before plaque formation remains a key area for further investigation. The damage to vascular endothelial cells (VECs) of Atherosclerosis (AS) caused by oxidized lipids promotes the adhesion and infiltration of leukocytes into the subintimal space. This process triggers monocytes to mature into tissue macrophages, which then absorb lipid particles and transform into foam cells2. These processes contribute to vascular inflammation. VECs play a crucial role not only in initiating the inflammatory response but also in regulating the progression of AS, particularly during the early stages before plaque formation3.

Excessive inflammation and pyroptosis of VECs are closely linked to the progression of AS4. A key driver of this process is the activation of the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which plays a central role in initiating cellular inflammation and pyroptosis5. As a major inflammasome, NLRP3 assembles and activates inflammatory complexes and caspase-1 through the adaptor protein ASC6. This, in turn, leads to the assembly of the GSDMD protein into membrane pores, promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18)7. Previous studies have demonstrated the critical role of NLRP3 in atherosclerosis models, highlighting it as an important therapeutic target for AS in precision medicine8.

Thioredoxin (TRX), a critical antioxidant protein, protects against free radical damage, prevents apoptosis, and supports cell growth9. Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) acts as an endogenous inhibitor of TRX by binding to it and disrupting its biological functions. Research has shown that TXNIP expression is significantly elevated in the vasculature of atherosclerotic mice, indicating its role in promoting the progression of AS10. Additionally, the TRX/TXNIP system is vital for redox-dependent signaling pathways, particularly in the redox-sensitive activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Despite these findings, the exact mechanism by which the TRX/TXNIP system regulates AS remains unclear11.

PCSK9, a secretory serine protease produced by the liver12, plays a critical role in cholesterol metabolism by binding to and degrading low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLR)13. This degradation reduces LDLR’s ability to clear low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) from the bloodstream, leading to elevated LDL-C levels and, consequently, an increased risk of AS14. As a result, PCSK9 has been identified as a significant genetic risk factor for various cardiovascular diseases, including AS15. Current research shows that both pharmacological and genetic inhibition of PCSK9 can effectively reduce the risk of AS by preserving the normal function of LDLR16.

Engaging in proper physical exercise has well-documented benefits for the cardiovascular system and can reduce the risk of AS through various molecular pathways17. Exercise enhances nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and boosts antioxidant defenses, reducing oxidative stress and improving endothelial function18. While continuous high-intensity exercise (HICT) may increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) has shown significant potential in mitigating complications associated with chronic cardiovascular conditions19. HIIT consists of alternating short bursts of high-intensity activity with periods of lower-intensity recovery20. Although the roles of inflammation, oxidative stress, and pyroptosis in cardiovascular diseases are well-established, effective prevention strategies remain elusive21,22,23. Notably, studies show that after three months of exercise, clinical volunteers experienced significant reductions in serum PCSK9 and LDL-C levels, suggesting a direct link between regular exercise and PCSK9 reduction18. However, the precise mechanisms by which exercise inhibits PCSK9 levels and affects related signaling pathways remain unclear.

This study hypothesizes that exercise intensity and mode (HIIT vs. MICT) differentially regulates oxidative stress, NLRP3/TXNIP signaling, and PCSK9 activity, thereby influencing endothelial pyroptosis and AS progression. Clarifying these mechanisms is essential for tailoring exercise regimens to halt endothelial dysfunction before irreversible plaque formation. These findings may assist in formulating more precise exercise prescriptions, therapeutic interventions, and clinical management strategies for AS.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 J mice (8 weeks old, n = 6; Control group) and male C57BL/6 J ApoE KO mice (8 weeks old, n = 6/each group) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (USA). The mice were housed under standard conditions: a temperature of 22 ± 2℃, 45%−55% humidity, and a 12-h light/dark cycle, with unrestricted access to deionized water and food.

AS was induced in the ApoE KO mice through a high-fat diet (HFD). HFD, irradiated mouse standard chow diet containing 42% kcal from milk fat and 0.2% cholesterol was provided to the mice. The ApoE KO mice were randomly divided into three groups: sedentary control (AS-S), moderate-intensity continuous training (AS-MICT), and high-intensity interval training (AS-HIIT), with 6 mice in each group. Before the experimental diets, all mice were fed a standard chow diet for three days, followed by a gradual transition to a HFD over another three days. The mice were fed this diet for 12 weeks to simulate early atherosclerotic vascular endothelial injury. Both the exercise training and HFD regimen lasted 12 weeks to establish the pathological features of early-stage AS.

Ethics declarations

All research procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University, following the"Regulations on the Management of Laboratory Animals of China"and the ethical standards of the same committee. All research procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University (No.2021101) and adhered to the regulations of the People’s Republic of China governing the management of laboratory animals. The study was performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Training protocol

The treadmill used in this study (SA101 C; SANS Biological Technology, Jiangsu, China) was specifically designed to evaluate the physiological and pathological responses of small experimental animals during exercise. Operating at 220 V, 50 Hz, it provided eight running lanes and had a speed control range of 0–100 m/min, with a precision of 0.01 m/min. Integrated with treadmill software, the system allowed continuous speed monitoring for accurate data collection.

The exercise training protocol followed established guidelines for animal exercise and training22. A standardized progressive exercise test was conducted to determine the maximum aerobic speed (MAS), which is used to gauge the maximum aerobic velocity in mice. Six mice were used to determine the maximum running speed on the treadmill. The training speeds for the MICT group (45% ~ 55% MAS) and the HIIT group (70% ~ 80% MAS) were determined using this method23.

Both the AS + MICT and AS + HIIT groups underwent a five-day adaptive training period before starting the official exercise program. During this adaptation phase, the mice ran on the treadmill for 10 min daily, with speeds gradually increased to 8 m/min (for MICT) and 15 m/min (for HIIT) from day 1 to day 5, respectively. The animals were acclimatized to their housing, diet, and treadmill exercise over one week. Following this adaptation, both groups underwent progressive speed training for 12 weeks, five days a week, according to the detailed exercise prescription outlined in Table 1. The treadmill remained at 0% incline throughout the study.

Animal weights were monitored weekly throughout the eight-week treadmill training and HFD period. At the end of the training and dietary intervention, the animals were euthanized by 1% pentobarbital sodium (1 ml/100 g) with intraperitoneal injection 24 h after their last exercise, the mice fasted for 6 h before euthanasia. Following dissection, aortic tissues and serum samples from mice were immediately frozen at −80 °C for subsequent molecular profiling and biochemical analyses. Segments of aortic tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin-embedded for histopathological and morphological examinations.

Vascular morphometry and immunohistochemical staining analysis

The thoracic aortas from the mice were dissected, and 5-µm-thick paraffin sections were prepared for vascular morphometric analysis using hematoxylin and eosin staining. To facilitate antigen retrieval, the tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, immersed in citrate buffer, and boiled for 5 min. Afterward, they were washed twice with PBS and blocked with 5% goat serum for 30 min.

The sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, washed three times with PBS, followed by a 1-h incubation at 37 °C with secondary antibodies. The sections were then washed again three times with PBS. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) color development was applied for 5 min, and the slides were rinsed with distilled water to remove excess stain. The tissue was counterstained with hematoxylin for 10 s, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (3 min per concentration), cleared in xylene for 5 min, mounted with resin, and examined under a light microscope (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany).

The primary antibodies used were GSDMD-N (1:200; Novus Biologicals, CO, USA) and NLRP3 (1:200; AIFang, Changsha, China). Immunostaining density was quantified using Image J software. All microscopic images were captured using a Leica DM4B upright metallurgical microscope (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany).

Vascular reactivity experiment

Fresh thoracic aortas were immediately placed in physiological salt solution (PSS) to preserve their integrity. Adherent tissues were carefully removed, and the aortas were cut into 3-mm rings. These rings were transferred to the chambers of the Multi Myograph System (DMT620; Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) to avoid damage to the vascular endothelium. The chambers were filled with warmed (37 °C) and oxygenated PSS (95% O₂, 5% CO₂) to maintain optimal experimental conditions, and vascular tension was continuously recorded using LabChart software.

To establish a baseline, the aortic rings were maintained under 0.5 g of tension for 90 min. They were then stimulated twice with KCl (60 mmol/L) in PSS. Endothelial integrity was assessed by testing the ability of acetylcholine (ACh, 10⁻5 M) to relax vessels precontracted with norepinephrine (NE, 10⁻⁷ M). Rings showing 80% or greater relaxation were considered to have intact endothelium.

After verifying endothelial function, the aortic rings were precontracted with NE (10⁻⁷ M) until maximal contraction and a stable tension curve were achieved. Cumulative concentration–response curves were generated for ACh (endothelium-dependent relaxation) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP; endothelium-independent relaxation) at concentrations ranging from 10⁻⁹ M to 10⁻5 M. Average concentration–response curves were then plotted.

Mice aorta rings culture

Fresh thoracic aortic rings from wild-type C57BL/6 J mice were immediately immersed in a culture medium. In brief, 3-mm wide aortic rings were placed in 2 ml of DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin. The rings were incubated with either the compound or vehicle control at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO₂ for 12 h.

To simulate the progression of AS in vitro, aortic rings were treated with PCSK9 protein (1000 ng/ml; MedChemExpress, New Jersey, USA). To assess the potential effects of the TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3 pathway on vascular function, specific inhibitors were applied: MCC950 (NLRP3 inhibitor), TXNIP-IN-1 (TXNIP inhibitor), and Ruscogenin (another TXNIP inhibitor), all from MCE (MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China). These inhibitors were added to the culture at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. After incubation, the aortic rings were either analyzed by western blot or mounted in the Multi Myograph System chambers for vascular reactivity testing.

Western blot analysis

Aortic tissues were lysed on ice for 1 h using a lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and 50 μg of protein per sample was used for western blot analysis. The proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate—polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature (22 °C) for 1 h before overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C.

After incubation with primary antibodies, the membranes were treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at 22 °C. Protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection reagent (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Image Lab 6.0 software was used to analyze the gray values of the bands, and the target protein levels were normalized to the internal control (β-actin).

The primary antibody for eNOS was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Primary antibodies for TRX, TXNIP, NLRP3, GSDMD, β-actin, and secondary antibodies were sourced from Proteintech (Proteintech Group, Wuhan, China). All other chemicals, unless otherwise noted, were purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA).

Serum biochemical analysis

Serum oxidative stress markers were evaluated using commercial assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) with three specific quantification approaches. Total Superoxide Dismutase (T-SOD) activity was determined through the xanthine oxidase-mediated hydroxylamine method, which quantifies SOD-mediated inhibition of superoxide anion generation. Glutathione Peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity was measured by monitoring the oxidation rate of reduced glutathione (GSH) to oxidized glutathione (GSSG) using hydrogen peroxide as substrate. Malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration was spectrophotometrically quantified via thiobarbituritic acid (TBA) reaction. All assays were performed in triplicate according to the manufacturer’s protocols, with results expressed as U/mL for enzymatic activities and nmol/mL for lipid peroxidation products.

Additionally, serum concentrations of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), LDL-C, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were quantified using specific assay kits from the same institute, following the manufacturer’s protocols. PCSK9 levels in the serum were measured using an ELISA kit from Abcam (Abcam, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as means ± standard deviation. For multiple group comparisons (three or more groups), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test was used for normally distributed data, and the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Dunn post hoc test was applied to non-normally distributed data. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software, California, USA), with a P-value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Effects of MICT and HIIT on body weight, oxidative stress indicators, and lipid profiles and vascular function in early-stage atherosclerotic mice

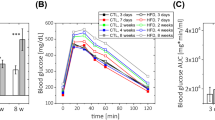

Body weight was measured weekly over eight weeks. Mice in the exercise training groups showed a significant reduction in body weight compared to the sedentary group (AS-S) (Fig. 1A; P < 0.05). Notably, both the MICT and HIIT groups exhibited significant weight differences from the AS-S group (both P < 0.05).

Effects of MCIT and HIIT on basic data and vascular function in atherosclerotic mice. The groups included wild-type mice (Control), ApoE KO HFD sedentary mice (AS-S), ApoE KO HFD mice undergoing moderate-intensity continuous training (AS-MICT), and ApoE KO HFD mice undergoing high-intensity interval training (AS-HIIT). Mice were trained on a treadmill following specific exercise protocols for 12 weeks. The following parameters were measured. Changes of (A) body weight were recorded. (B) T-SOD activity, (C) MDA, (D) GSH-Px, (E) TG, (F) TC, (G) HDL-C, and (H) LDL-C in the serum of mice were tested by kits. (I) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained images of aortas from each group. (J) and (K) The protein expression of eNOS in aortas was determined by western blotting. (L) ACh-induced relaxation and (M) SNP-induced relaxation of aortas were measured by vascular reactivity experiment. *P < 0.05, AS-S compared with Control; #P < 0.05, AS-MICT and AS-HIIT compared with AS-S. Data are presented as means ± SD.

To assess the impact of MICT and HIIT on oxidative stress, Total Superoxide Dismutase (T-SOD) activity, Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, and Glutathione Peroxidase (GSH-Px) were measured in the serum. T-SOD and GSH-Px levels were significantly lower in AS-S mice compared to the control group (Fig. 1B and D, P < 0.05), while levels in the AS-MICT and AS-HIIT groups were significantly higher than those in the AS-S group (P < 0.05). MDA, a marker of lipid peroxidation that reflects ROS production, was significantly decreased in both exercise training groups (MICT and HIIT) compared to the sedentary group (Fig. 1C, P < 0.05).

Additionally, serum levels of TG, TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C were measured. Results indicated that both MICT and HIIT significantly reduced levels of TG, TC, and LDL-C (Fig. 1E, F, and H, P < 0.05). Furthermore, only HIIT resulted in a significant increase in HDL-C levels compared to the AS-S group (Fig. 1G, I < 0.05).

To investigate the effects of MICT and HIIT on vascular structure and function during early AS, vascular morphology was examined. A 12-week high-fat diet led to increased blood lipid levels but did not result in significant plaque formation in the ascending aorta (Fig. 1I). This finding suggests that early AS may be present when endothelial damage begins to occur.

Dysregulation of NO production, driven by eNOS in VECs, is a key characteristic of vascular endothelial dysfunction. Western blot analysis revealed a significant decrease in eNOS expression in the aorta of AS-S mice compared to the control group (Fig. 1J and K; P < 0.05). In contrast, eNOS levels were significantly elevated in both the AS-MICT and AS-HIIT groups (both P < 0.05), with the HIIT group exhibiting the highest eNOS expression.

Endothelium-dependent diastolic dysfunction, marked by an impaired response to ACh in the aorta, is a prominent indicator of early vascular dysfunction. The impact of different exercise interventions on ACh- and sodium nitroprusside (SNP)-induced relaxation of the aorta was assessed. The results indicated a significant reduction in ACh-induced relaxation in AS-S mice compared to the control group (Fig. 1L; P < 0.05). Both MICT and HIIT significantly enhanced ACh-induced relaxation of the aorta (both P < 0.05). However, no significant differences were observed in SNP-induced vasodilation among the groups (Fig. 1M).

Effects of MICT and HIIT on PCSK9 Levels in different organs and effects of pcsk9 on eNOS expression and vasodilation function of aorta in atherosclerotic mice

PCSK9 is primarily secreted by parenchymal organs and plays a crucial role in reducing the LDLR capacity to scavenge LDL-C, thereby increasing the risk of AS. PCSK9 levels were measured in the liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, heart, aorta, and serum. As shown in Fig. 2A-C, PCSK9 levels were significantly elevated in the liver, kidney, heart, aorta, and serum of AS-S mice compared to the control group (all P < 0.05).

MICT and HIIT improve vascular function through inhibiting PCSK9 level. (A and B) PCSK9 expression in the liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, heart, and aorta was measured using western blotting. (C) PCSK9 levels in the serum were quantified via ELISA. *P < 0.05, AS-S compared with Control; #P < 0.05, AS-MICT and AS-HIIT compared with AS-S. Data are presented as means ± SD. (D and E) Protein expression of eNOS in aortic tissue, either Vehicle- or PCSK9-treated in vitro, was analyzed. (F) ACh-induced and (G) SNP-induced vasodilation function of in vitro-cultured aortas treated with or without PCSK9. *P < 0.05, Vehicle group compared with PCSK9 group. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Interestingly, the effects of MICT and HIIT on PCSK9 levels varied across different tissues. Both MICT and HIIT markedly increased PCSK9 levels in the liver (both P < 0.05), while their effects in other organs were opposite. Specifically, PCSK9 levels in the kidney and aorta were significantly lower in the AS-HIIT group compared to the AS-S group (both P < 0.05), but no significant difference was observed between the AS-MICT and AS-S groups. Additionally, both exercise modalities significantly reduced PCSK9 levels in the skeletal muscle of atherosclerotic mice (P < 0.05). Importantly, neither exercise mode had a significant effect on PCSK9 levels in heart tissue.

Crucially, as shown in Fig. 2C, serum PCSK9 levels were significantly decreased in both the AS-MICT and AS-HIIT groups compared to the AS-S group (both P < 0.05), with HIIT demonstrating a more pronounced inhibitory effect on PCSK9 than MICT.

To investigate the impact of PCSK9 on endothelial function, experiments were conducted using cultured aortic rings in vitro. As illustrated in Fig. 2D and E, PCSK9 treatment significantly reduced eNOS expression in the aorta (P < 0.05). Additionally, the ACh-induced relaxation test demonstrated that PCSK9 markedly impaired the endothelium-dependent vasodilatory function of the aorta (Fig. 2F, I < 0.05). however, it did not affect SNP-induced vasodilation (Fig. 2G).

Effects of MICT and HIIT on TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N Expression in the Aorta of Atherosclerotic Mice

The potential regulatory mechanisms by which MICT and HIIT improve vascular function in atherosclerotic mice were explored. The alterations in the TRX/TXNIP complex and NLRP3-induced pyroptosis in the aorta were initially assessed using western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, the balance of the TRX/TXNIP complex was disrupted in AS mice, indicated by increased TXNIP levels and decreased TRX levels. Furthermore, the protein expressions of NLRP3 and GSDMD-N were significantly elevated in the aorta of AS mice compared to normal mice (both P < 0.05). Similar results were confirmed through immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 3C and D). Importantly, both MICT and HIIT effectively restored the disturbed TRX/TXNIP complex and inhibited the elevated expressions of NLRP3 and GSDMD-N in the aortas of atherosclerotic mice.

MICT and HIIT inhibit the TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N signaling pathway in the aortas of atherosclerotic mice. (A and B) The protein expressions of TRX/TXNIP and NLRP3/GSDMD-N were detected by western blot. (C and D) Immunohistochemical staining was performed to detect NLRP3 and GSDMD-N in the aortas. *P < 0.05, AS-S compared with Control; #P < 0.05, AS-MICT and AS-HIIT compared with AS-S. Data are presented as means ± SD.

PCSK9 Impairs Vasodilation Function through TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N-Mediated Pyroptosis

The effect of PCSK9 on the activation of TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N was intially detected in the cultivating aorta in vitro.As shown in Fig. 4A and B, western blot analysis revealed significantly decreased TRX expression and increased levels of TXNIP, NLRP3, and GSDMD-N in aortas treated with PCSK9 (all P < 0.05). Subsequently, specific inhibitors—MCC950 (a selective NLRP3 inhibitor), TXNIP-IN-1 (a specific TXNIP inhibitor), and Ruscogenin (another TXNIP inhibitor)—were applied to assess the effects of the TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3 pathway on vascular function and pyroptosis in PCSK9-treated aortas. Western blot analysis demonstrated that the abnormal expressions of TRX, NLRP3, and GSDMD-N were significantly reversed by the TXNIP inhibitors (Fig. 4C and D, all P < 0.05). Furthermore, inhibition of NLRP3 effectively decreased the elevated expression of GSDMD-N (P < 0.05). Additionally, inhibiting both TXNIP and NLRP3 significantly upregulated the suppressed eNOS expression in PCSK9-treated aortas (all P < 0.05). Consequently, vasodilation tests revealed that inhibiting TXNIP and NLRP3 significantly improved endothelium-dependent diastolic dysfunction induced by PCSK9 (Fig. 4E and F).

PCSK9 impairs endothelial function through activating the TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N signaling pathway. (A and B) Protein expressions of TRX, TXNIP, NLRP3, and GSDMD-N were analyzed by western blotting in Vehicle- or PCSK9-treated aortas in vitro. MCC950 (a specific NLRP3 inhibitor), TXNIP-IN-1 (a specific TXNIP inhibitor), and Ruscogenin (another TXNIP inhibitor) were applied, with a final intervention concentration of 10 μg/ml for all inhibitors. (C and D) The protein expressions of TRX, TXNIP, NLRP3 and GSDMD-N were detected by western blot. (E) ACh-induced and (F) SNP-induced vasodilation in vitro of aortas treated with or without PCSK9. *P < 0.05, Vehicle group compared with PCSK9 group. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Discussion

AS significantly damages blood vessels in several ways. First, it reduces vascular wall function, impairing the ability of blood vessels to regulate blood pressure. Second, patients with AS may experience thrombosis due to endothelial damage, which leads to platelet aggregation and thrombus formation within blood vessels. Third, vascular stenosis can occur, resulting in ischemic conditions in tissues or organs, such as myocardial infarction and cerebral infarction. Lastly, secondary lesions associated with AS, including calcification and atheromatous ulcer formation, can further exacerbate vascular damage and elevate the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases24.

Given the challenges in reversing atherosclerotic plaque formation, this study focuses on preventing AS development at its early stages, prior to plaque formation. Early atherosclerotic lesions primarily manifest as spotty lipid streaks in the arterial intima and increased lipid deposition, leading to fibrous tissue proliferation and hyaline degeneration. Both of these changes are a consequence of vascular endothelial injury. To simulate early vascular endothelial injury in AS, ApoE knockout (KO) mice were utilized and fed a high-fat diet for 12 weeks, and 12 weeks of exercise during this period.

Our previous research has shown that different intensities of continuous training have distinct effects on oxidative stress and vascular inflammation in hypertensive rats22. Following similar methodologies, a tailored exercise regimen of MICT and HIIT was developed for the ApoE KO mice, mimicking clinical rehabilitation training paradigms. Evidence supports that both MICT and HIIT effectively reduce total body fat mass in adults and patients with AS25. In this study, it was found that both MICT and HIIT reduced body weight in atherosclerotic mice, with MICT proving more effective for weight loss, aligning with clinical findings in adults with metabolic syndrome. Furthermore, while previous studies suggest that HIIT offers greater cardiovascular benefits than MICT21, there is limited research directly comparing their effects on vascular endothelial function.

Endothelial dysfunction is associated with decreased NO production in blood vessels or compromised NO availability in AS26. As an endogenous vasodilator, NO plays a crucial role in regulating vascular morphology and reducing ROS production27. Disruption of eNOS expression impairs NO synthesis, ultimately contributing to vascular endothelial dysfunction28. The positive effects of exercise on endothelial function can be assessed through ACh-induced aortic endothelium-dependent relaxation, which relies on eNOS-mediated NO production. In this study, eNOS levels and endothelial-dependent vasodilation were measured to assess the extent of endothelial injury. Our findings indicate that both MICT and HIIT upregulated eNOS expression in the aorta of AS mice, thereby enhancing endothelial dilation function during the early stages of AS.

The inflammasome is a complex of multiprotein signaling pathways that includes NLRP1, NLRP3, AIM2, and NLRC4, which orchestrate host defense mechanisms against infections and physiological disturbances29. Among these, NLRP3 is particularly relevant to cardiovascular diseases and vascular endothelial function30. Previous studies have shown that excessive activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome occurs in the aorta of ApoE KO mice, and silencing NLRP3 can alleviate vascular inflammation and aortic remodeling31. NLRP3 has emerged as a critical initiator of cardiovascular diseases and plays a significant role in AS formation32. Cholesterol crystals present in atherosclerotic plaques can activate NLRP3 in macrophages, leading to cell apoptosis and accelerating AS progression. Conversely, genetic deletion of NLRP3 has been shown to inhibit inflammatory responses, endothelial barrier damage, fibrosis, and the formation of atherosclerotic plaques33. Targeting interleukin IL-1β, a primary product of the inflammasome, can mitigate vascular inflammation and AS by reducing the supply of inflammatory cells and their infiltration into atherosclerotic tissue34. Therefore, targeting NLRP3 in VECs represents a promising strategy for reducing the incidence of AS.

MICT, HIIT, and resistance training have demonstrated the ability to inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation in various pathological conditions, including diabetes35, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease36, and obesity37. Notably, aerobic exercise has been shown to mitigate AS by regulating fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and the harmful effects mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome on vascular tissue38. However, the precise mechanisms by which different types of exercise influence atherosclerotic inflammation are not fully understood. This gap limits the ability to establish evidence-based exercise prescriptions for managing AS. Our study confirmed that both MICT and HIIT downregulated the protein levels of NLRP3, TXNIP, and GSDMD-N in the vascular tissue of AS mice. These proteins are closely associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, and pyroptosis. Given that PCSK9 is widely recognized as a significant upstream factor in the development of AS39, it is proposed that the protective effects of exercise on endothelial function may involve the PCSK9-mediated activation of the TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N pathway.

To verify this hypothesis, the levels of PCSK9 in key solid organs, blood vessels, and serum were measured. Interestingly, exercise significantly increased PCSK9 expression in the liver while reducing it in the serum and blood vessels. It is speculated that exercise may promote the release of PCSK9 from the liver40, thereby regulating its stimulatory effect on vascular lipid metabolism.Another important finding was that exogenous administration of PCSK9 significantly elevated the expression of TXNIP, NLRP3, and GSDMD-N in in vitro-cultured aorta rings. Under conditions of oxidative stress, inflammation, and other harmful stimuli, TXNIP can be activated, leading to increased cholesterol synthesis and metabolism by inhibiting the antioxidant activity of TRX and promoting NLRP3 inflammasome activation41. Notably, there may be both direct and indirect interactions between PCSK9 and TXNIP. Specifically, TXNIP may regulate PCSK9 expression, while PCSK9 could influence TXNIP expression and activity by affecting the cellular redox state42.

Additionally, as a major activator of the NLRP3 inflammasome, ROS can facilitate the dissociation of the TRX-TXNIP complex, thereby enhancing the interaction between NLRP3 and TXNIP43. This physical interaction may explain how the inflammasome is activated in a ROS-sensitive manner, particularly in macrophages44. In our study, the relationship between TXNIP and NLRP3 was also confirmed using in vitro-cultured aorta rings. The results revealed a significant decrease in NLRP3 levels in the aorta when stimulated with TXNIP inhibitors. Furthermore, inhibiting TXNIP and NLRP3 effectively increased eNOS expression, reduced GSDMD-N levels, and restored endothelial function in PCSK9-treated aorta. These findings suggest that targeting the TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N pathway45 may elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which MICT and HIIT protect endothelial function in the early stages of AS.

The interaction between exercise and PCSK9 alterations is complex and multifactorial46. It is hypothesized that during intense muscle stimulation, specific metabolites or myokines are produced and released into the bloodstream during HIIT and MICT. These metabolites may influence PCSK9 generation as well as downstream TRX/TXNIP and NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis. Given that training intensity and methods differ, the activation of metabolic processes initiated by these metabolites or myokines is crucial in regulating the expression and secretion of PCSK947. This regulation can, in turn, disrupt redox homeostasis and lipid metabolism48. It is proposed that a metabolite threshold may explain the distinct vascular responses observed between MICT and HIIT. Additionally, investigating variations in myokine content across different exercise intensities and their related outcomes represents a promising research avenue to clarify the connections between exercise and cardiovascular health.

While both MICT and HIIT demonstrated protective effects on endothelial function, HIIT exhibited distinct mechanistic advantages over MICT in modulating key pathways linked to atherosclerotic progression. Notably, HIIT induced a more pronounced downregulation of NLRP3 inflammasome components (NLRP3, TXNIP, and GSDMD-N) in vascular tissues compared to MICT. This differential suppression aligns with previous reports that high-intensity stimuli preferentially inhibit inflammasome activation by amplifying antioxidant defenses and attenuating ROS-triggered TXNIP/NLRP3 interactions. Furthermore, HIIT enhanced hepatic PCSK9 expression while reducing its circulating levels, suggesting enhanced hepatic clearance of atherogenic lipoproteins—a regulatory pattern less evident in MICT. This dual modulation may synergistically mitigate lipid-driven endothelial injury, as PCSK9 overexpression in vessels directly activates TXNIP/NLRP3 signaling. Mechanistically, HIIT’s intermittent high-intensity bursts likely generate stronger metabolic stress, triggering myokine release (e.g., irisin, FGF21) that suppresses NLRP3 priming and pyroptosis more effectively than steady-state MICT. Clinically, HIIT’s superior NLRP3 pathway inhibition correlates with its established efficacy in improving cardiovascular outcomes in AS patients. However, MICT’s greater weight-reduction effect highlights context-dependent utility. These findings suggest that HIIT’s intensity-dependent metabolic perturbations may offer amplified protection against endothelial dysfunction by targeting both inflammasome activation and lipid regulation, warranting further investigation into optimal intensity thresholds for distinct AS phenotypes.

Study strengths and limitations

In clinical practice, the effects of exercise on vascular function and structure depend significantly on the characteristics of the training load, making the determination of exercise intensity in exercise prescriptions critical. The total running distance for the MICT and HIIT protocols were very close. Although the distances were not explicitly matched, the difference was minimal, and the primary focus of the study was to compare the effects of exercise intensity rather than total workload. It is essential to understand how different exercise modalities influence the development of AS. Our study demonstrated that both MICT and HIIT can protect vascular tissue from endothelial dysfunction during the early stages of AS. These findings may aid in the creation of more precise exercise prescriptions, therapeutic interventions, and clinical management strategies for AS.

However, it is important to recognize several limitations within this study. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, the duration of the exercise interventions was relatively short, and the long-term effects warrant further investigation. Thirdly, the control of exercise in animal studies and the extent to which such studies can be reliably applied to humans remains an open question, which will offer additional insights into the benefits of exercise versus inactivity. Future research should aim to address these limitations by employing larger sample sizes, longer intervention periods, and more precise exercise control methods to further validate the protective effects of exercise on vascular health and to refine exercise recommendations for the prevention and management of AS.

Besides, although the levels of PCSK9 and its downstream signaling pathways were assessed, the specific regulatory molecular mechanisms by which exercise influences PCSK9 levels remain partially unexplored. This aspect is the focus of ongoing research.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that both MICT and HIIT alleviated endothelium-dependent diastolic dysfunction in AS mice (Fig. 5). Among them, HIIT was more effective than MICT in ameliorating early atherosclerotic vascular injury in AS mice.These protective effects may be related to the inhibition of PCSK9-induced activation of the TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N pathway. This study provides scientific proof from basic research for the clinical practice of exercise prescription, and HIIT could be chosen more often to obtain the maximum benefit from exercise workouts. of course this needs to be considered in special cases such as the elderly and contraindications to exercise.

MICT and HIIT can alleviate endothelial-dependent vasodilation dysfunction in mice with atherosclerosis (AS) by suppressing the levels of PCSK9 in serum and blood vessels. These protective effects may be related to the blockade of the PCSK9-induced TRX/TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD-N pathway activation. Both types of training can effectively prevent the progression of endothelial dysfunction in the early stages of AS.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding and first authors.

References

Zhang, T. et al. Interaction between adipocytes and high-density lipoprotein:new insights into the mechanism of obesity-induced dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis. Lipids Health Dis. 18(1), 223 (2019).

Williams, J. W. et al. Single cell RNA sequencing in atherosclerosis research. Circ. Res. 126(9), 1112–1126 (2020).

Bułdak, Ł. Cardiovascular diseases-a focus on atherosclerosis, its prophylaxis, complications and recent advancements in therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(9), 4695 (2022).

Vasudevan, S. O., Behl, B. & Rathinam, V. A. Pyroptosis-induced inflammation and tissue damage. Semin. Immunol. 69, 101781 (2023).

Lorenzo, Loffredo., Roberto, Carnevale. Oxidative Stress: The Hidden Catalyst Fueling Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 13(9):1089. (2024).

Li, M. et al. Programmed cell death in atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. Cell Death Dis. 13(5), 467 (2022).

De Meyer, G., Zurek, M., Puylaert, P. & Martinet, W. Programmed death of macrophages in atherosclerosis: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21(5), 312–325 (2024).

Qian, Z. et al. Pyroptosis in the Initiation and Progression of Atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol. 12, 652963 (2021).

Ali, A. A. G., Niinuma, S. A., Moin, A. S. M., Atkin, S. L. & Butler, A. E. The role of platelets in hypoglycemia-induced cardiovascular disease: A review of the literature. Biomolecules 13(2), 241 (2023).

Bradford, H. F. et al. Thioredoxin is a metabolic rheostat controlling regulatory B cells. Nat. Immunol. 25(5), 873–885 (2024).

Choi, E. H. & Park, S. J. TXNIP: A key protein in the cellular stress response pathway and a potential therapeutic target. Exp. Mol. Med. 55(7), 1348–1356 (2023).

Seidah, N. G. & Prat, A. The Multifaceted Biology of PCSK9. Endocr. Rev. 43(3), 558–582 (2022).

Ding, Z., Pothineni, N., Goel, A., Lüscher, T. F. & Mehta, J. L. PCSK9 and inflammation: role of shear stress, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and LOX-1. Cardiovasc. Res. 116(5), 908–915 (2020).

Hummelgaard, S., Vilstrup, J. P., Gustafsen, C., Glerup, S. & Weyer, K. Targeting PCSK9 to tackle cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 249, 108480 (2023).

Bao, X. et al. Targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): from bench to bedside. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 9(1), 13 (2024).

Matyas, C. et al. PCSK9, A promising novel target for age-related cardiovascular dysfunction. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 8(10), 1334–1353 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. The effects of high-intensity interval training/moderate-intensity continuous training on the inhibition of fat accumulation in rats fed a high-fat diet during training and detraining. Lipids Health Dis. 23(1), 221 (2024).

Tucker, W. J. et al. Exercise for Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: JACC Focus Seminar 1/4. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80(11), 1091–1106 (2022).

Gripp, F. et al. HIIT is superior than MICT on cardiometabolic health during training and detraining. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 121(1), 159–172 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. High-Intensity Interval Training and Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training Attenuate Oxidative Damage and Promote Myokine Response in the Skeletal Muscle of ApoE KO Mice on High-Fat Diet. Antioxidants (Basel). 10(7), 992 (2021).

Qiu, Y. et al. Exercise sustains the hallmarks of health. J Sport Health Sci. 12(1), 8–35 (2023).

Luo, M. et al. Effects of different intensities of continuous training on vascular inflammation and oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25(17), 8522–8536 (2021).

Luo, M. et al. Aerobic exercise inhibits renal EMT by promoting irisin expression in SHR. iScience. 26(2), 105990 (2023).

Jebari-Benslaiman, S. et al. Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(6), 3346 (2022).

Xiao, Y. et al. The effects of short-term high-fat feeding on exercise capacity: multi-tissue transcriptome changes by RNA sequencing analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 16(1), 28 (2017).

Xu, S. et al. Endothelial Dysfunction in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases and Beyond: From Mechanism to Pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol. Rev. 73(3), 924–967 (2021).

Zhang, A. et al. High-fat stimulation induces atrial neural remodeling by reducing NO production via the CRIF1/eNOS/P21 axi. Lipids Health Dis. 22(1), 189 (2023).

Yao, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, C. Klotho ameliorates oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL)-induced oxidative stress via regulating LOX-1 and PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathways. Lipids Health Dis. 16(1), 77 (2017).

Fu, J. & Wu, H. Structural Mechanisms of NLRP3 Inflammasome Assembly and Activation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 41, 301–316 (2023).

Li, T., Yang, J., Tan, A. & Chen, H. Irisin suppresses pancreatic β cell pyroptosis in T2DM by inhibiting the NLRP3-GSDMD pathway and activating the Nrf2-TrX/TXNIP signaling axis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 15(1), 239 (2023).

Zhuang, T. et al. Endothelial foxp1 suppresses atherosclerosis via modulation of Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Circ. Res. 125(6), 590–605 (2019).

Kong, P. et al. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7(1), 131 (2022).

Hsu, C. C. et al. Hematopoietic NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasomes promote diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis, but increased necrosis is independent of pyroptosis. Diabetes 72(7), 999–1011 (2023).

Ding, Z. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome via IL-1β regulates PCSK9 secretion. Theranostics. 10(16), 7100–7110 (2020).

Sun, Y. & Ding, S. NLRP3 inflammasome in diabetic cardiomyopathy and exercise intervention. Int J Mol Sci. 22(24), 13228 (2021).

Zhu, J. Y., Chen, M., Mu, W. J., Luo, H. Y. & Guo, L. Higd1a facilitates exercise-mediated alleviation of fatty liver in diet-induced obese mice. Metabolism 134, 155241 (2022).

Vandanmagsar, B. et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 17(2), 179–188 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Interactions between PCSK9 and NLRP3 inflammasome signaling in atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 14, 1126823 (2023).

Alessia, Silla., Federica, Fogacci., Angela, Punzo., Silvana, Hrelia., Patrizia, Simoni., Cristiana, Caliceti., Arrigo F G, Cicero. Treatment with PCSK9 Inhibitor Evolocumab Improves Vascular Oxidative Stress and Arterial Stiffness in Hypercholesterolemic Patients with High Cardiovascular Risk. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023. 12(3):578.

Li, W. et al. Aerobic exercise training inhibits neointimal formation via reduction of PCSK9 and LOX-1 in atherosclerosis. Biomedicines. 8(4), 92 (2020).

Zhou, R., Tardivel, A., Thorens, B., Choi, I. & Tschopp, J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat. Immunol. 11(2), 136–140 (2010).

Woo, S. H. et al. TXNIP suppresses the osteochondrogenic switch of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 132(1), 52–71 (2023).

Omer, M. A. et al. Exploring immune redox modulation in bacterial infections: insights into thioredoxin-mediated interactions and implications for understanding host-pathogen dynamics. Antioxidants (Basel). 13(5), 545 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Mitochondrial ROS promote macrophage pyroptosis by inducing GSDMD oxidation. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11(12), 1069–1082 (2019).

Yu, H. et al. High-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training on patient quality of life in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 13915 (2023).

Tirandi, A., Montecucco, F. & Liberale, L. Physical activity to reduce PCSK9 levels. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 988698 (2022).

Sulague, R. M., Suan, N. N. M., Mendoza, M. F. & Lavie, C. J. The associations between exercise and lipid biomarkers. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 75, 59–68 (2022).

Ding, P., Song, Y., Yang, Y. & Zeng, C. NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis in cardiovascular diseases and exercise intervention. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1368835 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (No. CSTB2022 NSCQ-MSX0111 and No. CSTB2024 NSCQ-MSX1212), Key research project of Exercise Medicine College of Chongqing Medical University (TY202301), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 82400477 and No. 82400516), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M730505). We thank Assistant Researcher Yunfei Mo of the Experimental Animal Centre of Chongqing Medical University for participating in our experiments.

Funding

This work was sponsored by Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (No. CSTB2022 NSCQ-MSX0111 and No. CSTB2024 NSCQ-MSX1212), Key research project of Exercise Medicine College of Chongqing Medical University (TY202301), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 82400477 and No. 82400516), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M730505).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guochun Liu designed the exercise prescriptions, participated in data analysis, funded this study, completed the graphic abstract, and wrote the article; Minghao Luo and Ruiyu Wang designed the experimental programs, supervised the research, funded this study, and conducted data analysis; Binyi Zhao participated in manuscript revision; Xiang Li, Xuejiao Zhu, and Mengdie Zhang participated in animal experiments; Maowei Duan, Qinglong Chen, and Zhuohan Liu participated in animal treadmill training experiments; Xuan Wen, Jia Guo, and Man Zheng were involved in reviewing the data. Ruiyu Wang and Minghao Luo wrote and submitted the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All research procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University (No.2021101) and adhered to the regulations of the People’s Republic of China governing the management of laboratory animals.

Informed consent

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to the order of authorship.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, G., Zhao, B., Chen, Q. et al. HIIT and MICT mitigate endothelial dysfunction in early atherosclerotic mice via PCSK9 inhibition. Sci Rep 15, 30411 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05206-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05206-7