Abstract

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in Korea has risen in recent years, yet many cases remain undiagnosed. Advanced artificial intelligence models using multi-modal data have shown promise in disease prediction, but two major challenges persist: the scarcity of samples containing all desired data modalities and class imbalance in T2DM datasets. We propose a novel transfer learning framework to predict T2DM onset within five years, using two Korean cohorts (KoGES and SNUH). To utilize unpaired multi-modal data, our approach transfers knowledge between clinical and genetic domains, leveraging unpaired clinical data alongside paired data. We also address class imbalance by applying a positively weighted binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss and a weighted random sampler (WRS). The transfer learning framework improved T2DM prediction performance. Using WRS and weighted BCE loss increased the model’s balanced accuracy and AUC (achieving test AUC 0.8441). Furthermore, combining transfer learning with intermediate data fusion yielded even higher performance (test AUC 0.8715). These enhancements were achieved despite limited paired multi-modal samples. Our framework effectively handles scarce paired data and class imbalance, leading to improved T2DM risk prediction. This approach can be adapted to other medical prediction tasks and integrated with additional data modalities, potentially aiding earlier diagnosis and better disease management in clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of T2DM among Koreans has increased significantly in recent years, yet a substantial portion of cases remains undiagnosed. According to the Korean Diabetes Association, only 65.8% of the estimated population aged 30 or older with T2DM were aware of their condition in 2019–20201. Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial for preventing disease progression and managing complications. T2DM is largely preventable, as its onset can be mitigated through timely detection and lifestyle interventions. Previous studies have demonstrated that interventions targeting high-risk individuals can significantly reduce the development of T2DM2,3. Early diagnosis not only helps reduce diabetes-related complications but also alleviates the financial burden on healthcare systems4. These observations underscore the importance of early diagnosis and prevention of T2DM, highlighting the urgent need for proactive measures to impede disease progression5.

Both environmental and genetic factors contribute significantly to the onset of T2DM. Individuals with a family history of T2DM face a higher risk of developing the disease compared to those without such a history. Notably, the risk is greater if the mother has T2DM as opposed to the father6. Furthermore, genome-wide association studies have identified numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with T2DM, suggesting that integrating genetic information with clinical data could provide more accurate predictive models7. However, collecting paired genetic and clinical data from the same individuals is challenging and often results in limited sample sizes that may not fully represent the population.

Recent advances in AI have enabled novel approaches to disease diagnosis and prediction8. A variety of computational techniques have been applied to T2DM prediction, ranging from traditional methods like logistic regression and support vector machines (SVMs) to modern artificial neural networks (ANNs)9. For example, Mani et al. demonstrated the feasibility of machine learning-based T2DM risk prediction using electronic medical record (EMR) data, successfully identifying high-risk populations for early intervention10. Modern multi-modal modeling approaches have further enhanced T2DM prediction capabilities. Hahn et al. showed improved prediction performance by combining genome-wide polygenic risk scores with metabolomic profiles, though their approach required fully paired data across all modalities11. Similarly, Lee et al. developed a multi-task learning framework incorporating genetic, nutritional, and clinical data, and Lim et al. introduced a progressive self-transfer learning framework for temporal health data12,13. However, these approaches are limited by the need for complete multi-modal datasets for each individual.

Multi-modal data analysis has emerged as a powerful strategy in medical analytics14,15, but obtaining comprehensive datasets that include all relevant modalities (clinical, demographic, laboratory, etc.) for the same individuals remains difficult. Recent studies have further extended this multimodal approach. For instance, Kim et al. leveraged continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) to assess cardiovascular risks in high-risk T2DM patients, focusing on personalized prediction using high-frequency physiological time-series data16. Similarly, Lee et al. employed large language multimodal models (LLMs) to integrate unstructured clinical notes with lab data from electronic health records (EHRs), demonstrating the power of deep contextual understanding for early diagnosis17. While these models show strong performance, they often rely on real-time infrastructure or natural language processing pipelines that may not be scalable in broader population-based settings. These limitations highlight the need for a more flexible and scalable approach to multimodal integration. To address the challenges of incomplete data pairing and class imbalance−while maintaining high predictive accuracy−we propose a novel transfer learning framework that learns from structured clinical and genetic data drawn from two population-based cohorts. Our method does not require full modality alignment, and incorporates algorithm- and data-level interventions to effectively manage class imbalance and enhance model robustness. For instance, Luo and Zhao developed an autoregressive exogenous model that combines transfer learning and incremental learning for blood glucose prediction18. Yu et al. further advanced this idea by integrating instance-based and network-based transfer learning, demonstrating the effectiveness of transfer learning in scenarios with limited data19.

Transfer learning has shown considerable promise in medical applications, especially when the source and target domains share similar feature spaces or underlying patterns. In T2DM prediction, clinical examination data and genetic information are inherently linked through biological mechanisms, suggesting that knowledge learned from clinical data could usefully initialize models that incorporate genetic information. While transfer learning has achieved remarkable success in computer vision, its potential for combining clinical and genetic data in T2DM prediction remains largely unexplored. Current approaches either focus exclusively on clinical data or require fully paired datasets, failing to leverage the vast amount of unpaired clinical data available in healthcare systems.

In imbalanced medical datasets such as T2DM cohorts, the minority class (patients who develop the disease) is vastly outnumbered by healthy cases, leading models to bias toward the majority class. Past studies have attempted to mitigate this issue with oversampling or undersampling strategies and cost-sensitive learning, but each has limitations—oversampling can cause overfitting and undersampling may discard important information20. To address this, we applied a positively weighted binary cross-entropy loss and a weighted random sampler, a novel combination of algorithm-level and data-level interventions that rebalances the training process. This approach improved the model’s ability to detect rare T2DM cases, boosting sensitivity and balanced accuracy compared to conventional training. By effectively handling class imbalance, our framework contributes a more robust predictive modeling strategy for T2DM and similar medical prediction tasks, where minority outcomes are crucially important.

In this study, our primary objective is to improve the prediction of T2DM onset within a five-year timeframe by developing a novel transfer learning framework that utilizes unpaired multi-modal data from two Korean cohorts: the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) and a health examination dataset from Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH). Our framework integrates a transfer learning scheme (leveraging unpaired clinical data from the larger KoGES cohort) with an intermediate data fusion strategy to effectively combine clinical and genetic features in a unified model. Our approach tests two key hypotheses: first, that transfer learning from a larger cohort’s clinical data improves prediction performance compared to training a model from scratch; and second, that knowledge learned from a clinical-only model can enhance the performance of a multi-modal model that integrates clinical and SNP features. Additionally, we address the class imbalance problem in T2DM prediction by applying interventions at both the data level and the model level21. This comprehensive approach targets both the challenge of limited paired multi-modal data and the issue of imbalanced datasets, with the goal of producing more robust and practical T2DM prediction models for the Korean population.

In summary, this work offers several key contributions: First, we present a novel transfer learning-based multi-modal framework for T2DM prediction that leverages unpaired clinical and genetic datasets from two large cohorts. Second, we design an intermediate data fusion strategy to integrate clinical and genetic features, which−when combined with transfer learning−significantly improves predictive performance despite limited paired data. Third, we address the class imbalance issue by applying a positively weighted loss function and a weighted random sampler, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to detect individuals who will develop T2DM (improving sensitivity and balanced accuracy). Fourth, we evaluate our approach on two independent cohorts, demonstrating superior performance (test AUC 0.8715) compared to baseline models and previous studies. Collectively, these contributions advance the state of the art in T2DM risk prediction and highlight practical methods for utilizing unpaired multi-modal data and handling class imbalance in medical AI.

Methods

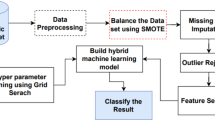

We now present the details of our experimental methodology. Figure 1 provides an overview of the entire workflow of this study, illustrating the key stages from the initial problem formulation to the final evaluation of results. As shown in the figure, the process is composed of multiple sequential steps, which are described in detail below.

In the following subsections, we describe each step of the proposed workflow in detail.

Dataset

This study utilized data from two sources: genetic (SNP) profiles of 79,835 individuals and epidemiological (clinical) records of 40,940 individuals, obtained from KoGES and the SNUH Health Examination Center. KoGES is a large-scale prospective cohort study funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, and the Ministry of Health and Welfare. Its primary objectives include addressing public health issues and laying the groundwork for future personalized and preventive healthcare strategies. The collected dataset comprises genotype information (including Korean Chip array data) and clinical examination records, all linked by unique patient identifiers. We defined differential follow-up periods based on T2DM outcomes: 5 years for participants who developed T2DM during follow-up, and 10 years for those who remained T2DM-free. T2DM was defined by any of the following criteria22:

-

1.

Fasting plasma glucose \(\ge\) 126 mg/dL

-

2.

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) \(\ge\) 6.5%

-

3.

Currently receiving treatment for diabetes

-

4.

Previous diagnosis of diabetes by a physician

Over the follow-up period, 2844 individuals (6.9%) were diagnosed with T2DM based on these criteria, while 38,096 (93.1%) remained non-diabetic. We utilized both SNP and clinical data relevant to T2DM. Out of 127,711 SNPs common to the KoGES and SNUH datasets, we selected 110 SNPs associated with T2DM based on genome-wide association study (GWAS) results (Supplementary Table S1 for the SNP list). After removing individuals with any missing data among these SNPs, the final genetic dataset included 77,362 individuals. For the clinical dataset, we included a total of 18 variables in the analysis: fasting blood sugar (FBS), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), triglycerides (Tg), body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), age, sex, history of hypertension, history of hyperlipidemia, exercise habits, smoking status, alcohol consumption, white blood cell count (WBC), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), creatinine (Cr), family history of diabetes, and waist circumference. We applied the following criteria to identify and remove outliers in the clinical data: SBP exceeding 200 mmHg, ALT exceeding 200 IU/L, WBC count below 2000/\(\upmu\)L or above 20,000/\(\upmu\)L, and Cr levels surpassing 2 mg/dL. Any clinical record meeting any of these criteria was excluded. After removing outliers and records with missing values, a total of 40,579 clinical samples remained. All continuous and ordinal variables were normalized to a [0, 1] range. Triglyceride values were log-transformed prior to normalization due to their wide range. The nominal variable (sex) was one-hot encoded. Ultimately, our integrated analysis included 19 clinical features. Merging the genetic and clinical datasets by common individual identifiers yielded 32,307 samples containing both SNP and clinical information. We used this integrated subset for model development that required paired data (e.g., for transfer learning fine-tuning). The data were randomly split into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 6:2:2 (60% training, 20% validation, 20% test) (Fig. 2).

Data imbalance

To address the class imbalance between non-diabetic and T2DM cases, we employed two strategies: (1) a BCE loss function with positive class weighting, and (2) a weighted random sampler (WRS). Each strategy was applied to the same DNN architecture to allow a consistent and fair performance comparison. For the data-level approach, we applied class weights during training so that minority-class (T2DM-positive) samples had a higher chance of being selected in each batch. Without weighting, each sample has equal selection probability (1/N, where N is the total number of samples), which biases training toward the majority class. We adjusted the sampling probabilities (Eq. 1) by assigning a larger weight to minority-class samples and a smaller weight to majority-class samples, increasing the likelihood that a minority-class sample is drawn in each batch. We implemented this weighted sampling approach using PyTorch’s WRS23 (Fig. 3).

At the model level, we used a weighted BCE loss function (with logits). We assigned a greater loss weight to positive (T2DM) examples so that the model training emphasized the minority class. This means that information from T2DM-positive samples influences the gradients more than information from the negative samples. By incorporating these weights into the loss calculation (Eq. 2), the model is guided to improve recall for the minority class. In Eq. 2, c denotes the number of classes (with \(c = 1\) for binary classification), n indexes the sample, and w is the weight for the positive class. Setting \(w > 1\) increases recall, whereas \(w < 1\) emphasizes precision24.

In addition to our main strategies (positively weighted BCE and weighted random sampling), we also included a widely used data-level oversampling technique, SMOTE-NC (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique for Nominal and Continuous features), for comparison purposes25. This method generates synthetic minority-class samples by interpolating between existing instances, while preserving categorical feature values, making it suitable for datasets with mixed feature types. Although SMOTE-NC is not the focus of this study, we applied it to the training set to benchmark its effectiveness against the class imbalance mitigation strategies proposed in this work. The oversampling was applied only to the training data, and the same DNN model architecture was used to ensure a fair comparison across all methods.

Model architecture

Transfer learning with multi-modal data integration

Given the limited availability of samples containing all data modalities, we employed a transfer learning strategy to leverage information from unpaired single-modality data. Our approach consists of a two-phase training scheme that builds from a single-modality model to a multi-modality model. In the first phase (single-modality pretraining), we developed and optimized a base neural network using only the clinical features from the larger KoGES cohort. This fully connected network was tuned extensively (exploring various network depths, activation functions, optimizers, and dropout rates) and trained on the KoGES clinical dataset (with an internal training/validation split); the best model was selected based on validation AUC and balanced accuracy. We then examined whether the knowledge captured by this model could improve performance on the smaller SNUH cohort. To test this, we trained multiple models on the SNUH clinical data under two conditions: one set of 100 models trained from scratch with random weight initialization, and another 100 models initialized with the weights from the KoGES-trained clinical model. The network architecture and hyperparameters were kept identical for both conditions to ensure a fair comparison. This preliminary experiment isolated the effect of transfer learning by evaluating whether a model initialized with knowledge from the larger cohort (KoGES) can outperform a model trained de novo on the smaller cohort (SNUH). In the second phase (multi-modal fine-tuning), we incorporated the genetic features to evaluate transfer learning in a multi-modal context. We constructed a combined model that integrates both clinical and SNP inputs through an intermediate fusion approach (detailed in the following subsection). For the transfer learning variant, the clinical branch of this multi-modal network was initialized with the pre-trained weights from the Phase 1 KoGES clinical model, while the genetic branch was initialized with random weights. We trained this multi-modal model on the SNUH dataset and compared its performance to an identical model trained from scratch (no transferred weights). Similar to Phase 1, we repeated the training with 100 different random train, validation, and test splits for each scenario to ensure robust evaluation. Model performance was assessed using accuracy, AUC, sensitivity, and specificity. This two-phase experimental design allowed us to quantify the benefit of transfer learning at both the single-modality level and the combined multi-modal level under consistent conditions.

Transfer learning with intermediate fusion

Building on the transfer-learning strategy described above, we implemented a multi-modal neural network that fuses two data modalities via an intermediate-fusion approach. The architecture comprises two parallel subnetworks−one for clinical information and one for genetic (SNP) information−that are merged at an intermediate layer (Fig. 4). The clinical branch is a fully connected network (FCN) whose weights are initialized with a model pre-trained on the large pool of unpaired clinical data from the KoGES and SNUH cohorts. This branch transforms the clinical features into a latent representation. The genetic branch is a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN) that processes the sequential SNP array, extracts local genotype patterns, and produces latent genetic feature vectors. These vectors are flattened into a single vector. At the fusion layer, the modality-specific latent vectors are concatenated to form a unified representation that preserves information from both sources. This fused representation is then passed through additional fully connected layers and, finally, through a sigmoid output unit that yields a predicted probability of T2DM in the range 0–1 (Fig. 4). We further tuned the hyperparameters of this integrated model using training and validation sets containing paired clinical and genetic data, selecting the final configuration on the basis of validation AUC and balanced accuracy. The intermediate-fusion strategy allows each modality-specific subnetwork to learn patterns independently before merging, thereby preserving each data type’s unique contribution during training. Table 1 summarizes the final parameter settings of the two subnetworks.

Transfer learning model structure. The clinical data branch (blue) is a fully connected network initialized with weights pre-trained on clinical data alone. The genetic data branch (green) is a 1D convolutional network processing SNP features. Latent representations from both branches are fused (concatenated) and fed into further layers to predict T2DM risk.

Baseline models for comparison

To benchmark the proposed transfer-learning model, we evaluated one classical machine-learning model, two deep-learning baselines, and an additional graph-based baseline. XGBoost is a gradient-boosted decision-tree ensemble trained on a single concatenated feature vector that includes both clinical variables and genetic (SNP) features. Basic DNN denotes a standard deep neural network that processes the same concatenated clinical-genetic feature vector using only fully connected layers, without any feature-fusion modules or transfer learning. Intermediate Fusion (no transfer) refers to a multi-modal network with separate clinical and SNP branches merged at an intermediate layer−architecturally identical to our proposed model−yet trained from scratch with randomly initialized weights. MGCN-CalRF is a graph-based multi-modal model adapted from26. This approach constructs a graph for each input modality (except the clinical features, which are used directly without graph transformation) and applies a graph convolutional network (GCN) to each modality-specific graph to extract learned feature representations. The outputs of these 3-layer GCNs (one per non-clinical modality) are concatenated with the raw clinical feature vector and fed into a Random Forest classifier. To produce well-calibrated predictions, the Random Forest is wrapped with a sigmoid-based calibrated classifier as in26. We set the GCN dropout rate to 0.5 and optimize its weights using stochastic gradient descent. The Random Forest consists of 100 trees and outputs the final prediction. All models (baselines and the proposed model) were trained and evaluated on identical training, validation, and test splits and underwent the same preprocessing pipeline, including the weighted random sampler and positively weighted BCE loss to address class imbalance. For XGBoost, scale_pos_weight was set to match the positive-class prevalence. Hyperparameters for each model were tuned via grid search on the validation set, and the best configurations were selected according to validation performance. Final evaluation on the test set compared accuracy, \(\hbox {F}_1\) score, \(\hbox {F}_2\) score, AUC, sensitivity, and specificity across models. The full hyperparameter settings of the four baseline models are provided in Supplementary Tables S2–S4.

Results

Study population characteristics

Of the 32,307 individuals in our final integrated dataset, 1999 were diagnosed with T2DM during the follow-up period and 30,308 remained non-diabetic. We observed significant differences in multiple features between those who developed T2DM and those who did not. The T2DM group had higher baseline values for age, BMI, SBP, DBP, HbA1c, FBS, triglycerides, WBC, ALT, and waist circumference compared to the non-T2DM group. Additionally, the T2DM group had a higher proportion of males, a greater prevalence of family history of diabetes, higher rates of alcohol consumption and smoking, and a higher prevalence of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Notably, the T2DM group also had a lower frequency of regular exercise (exercise frequency was categorized as Never, Occasionally [< 2–3 times/week, < 30 min/session], or Regularly [\(\ge\)2–3 times/week, \(\ge\)30 min/session]) (Table 2).

Effectiveness of transfer learning

In our preliminary transfer learning experiment, we found that models with transferred weights performed similarly to those trained from scratch. Over 100 iterations on the SNUH dataset, the models trained from scratch (random initialization) achieved an average accuracy of 0.8234, sensitivity of 0.7832, specificity of 0.8274, and AUC of 0.8952. The models initialized with weights pre-trained on KoGES clinical data achieved a comparable average accuracy of 0.8205, sensitivity of 0.7796, specificity of 0.8246, and AUC of 0.8971. These differences were not statistically significant. However, the highest single-run AUC observed among all 100 models was achieved by a model using the transfer learning approach (with KoGES-initialized weights) (Table 3).

Effectiveness of data imbalance handling

We next evaluated the impact of our class-imbalance countermeasures. Five approaches were compared on the test dataset: one using a standard (unweighted) BCE loss (no class weighting or oversampling), one using a positively weighted BCE loss (pw_BCE), one using a weighted random sampler (WRS), one combining pw_BCE with WRS, and one using synthetic minority oversampling tailored for mixed data (SMOTE-NC). The standard BCE model exhibited extremely high specificity (0.9979) but very low sensitivity (0.0727), resulting in a balanced accuracy of 0.5353 and an AUC of 0.8178 (Table 4). Incorporating a positive class weight in the loss function (pw_BCE) improved sensitivity to 0.8170 (with specificity dropping to 0.6941), raising the balanced accuracy to 0.7556 and slightly improving AUC to 0.8275. Similarly, using WRS increased sensitivity to 0.6541 while maintaining a high specificity of 0.8587, yielding a balanced accuracy of 0.7564 and the highest AUC (0.8458) among the single-strategy models. The combination of pw_BCE + WRS achieved the best overall balance between recall and precision, with sensitivity 0.7419, specificity 0.7835, balanced accuracy 0.7627, and AUC 0.8477. By contrast, the SMOTE-NC oversampling approach attained a sensitivity of only 0.2105, translating to a much lower balanced accuracy of 0.5905 and an AUC of 0.8263. These results confirm that both the pw_BCE and WRS strategies effectively mitigate performance degradation due to class imbalance, outperforming the SMOTE-NC oversampling method (Table 4).

In a 100-iteration validation analysis, the standard (unweighted) BCE loss function achieved an average balanced accuracy of approximately \(0.5496 \pm 0.0337\) and an AUC of \(0.8161 \pm 0.0050\). Applying a positively weighted BCE (pw_BCE) raised the balanced accuracy to \(0.7493 \pm 0.0066\) and the AUC to \(0.8272 \pm 0.0048\). Using a weighted random sampler (WRS) yielded a balanced accuracy of \(0.7658 \pm 0.0064\) and an AUC of \(0.8435 \pm 0.0044\). The combination of both strategies (pw_BCE+WRS) performed best, with the highest balanced accuracy of \(0.7665 \pm 0.0068\) and an AUC of \(0.8442 \pm 0.0045\). In contrast, the SMOTE-NC oversampling strategy achieved a much lower mean balanced accuracy of approximately \(0.5865 \pm 0.0050\) and an AUC of \(0.8246 \pm 0.0031\) in this 100-run analysis (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6), underscoring the inferior effectiveness of synthetic oversampling compared to our weighting and sampling approach. These improvements indicate that both the weighting scheme and oversampling effectively mitigate the performance degradation caused by class imbalance. Figure 5 and Supplementary Tables S5 and S6 illustrate the distribution of balanced accuracy and AUC across the 100 runs for each method, showing a clear upward shift in performance when using WRS and/or pw_BCE compared with the standard approach.

Performance distributions across 100 independent runs for five class-imbalance handling strategies−SMOTE oversampling, unweighted binary cross-entropy loss (standard BCE), probability-weighted BCE (pw_BCE), weighted random sampling (WRS), and the combined pw_BCE + WRS approach−evaluated on the (A) validation and (B) held-out test sets. Each box-and-whisker plot shows the spread of four metrics (left-to-right): \(\hbox {F}_1\)-score, \(\hbox {F}_2\)-score, AUROC, and balanced accuracy. Horizontal brackets denote pair-wise differences assessed with two-sided paired t-tests (ns = not significant; * \(p<0.05\); ** \(p<0.01\); *** \(p<0.001\); **** \(p<0.0001\)).

Model architecture enhancement

As summarized in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Tables S7 and S8, the transfer learning model demonstrates superior performance across most evaluation metrics compared to the baseline models (XGBoost, DNN, intermediate fusion, and MGCN-CalRF). Specifically, it achieved a sensitivity of \(0.8071 \pm 0.0362\), notably higher than DNN (\(0.7250 \pm 0.0240\)) and MGCN-CalRF (\(0.3696 \pm 0.0134\)) by 8.2 and 43.7 percentage points, respectively, and dramatically higher than XGBoost’s \(0.2936 \pm 0.2233\) (by over 50 points), although slightly lower than intermediate fusion (\(0.8411 \pm 0.0132\)). In the best-performing model comparison, the transfer learning approach reached a sensitivity of 0.8546, surpassing the best intermediate fusion model (0.8271; Table 5).

Conversely, the transfer learning model’s specificity (\(0.7784 \pm 0.0506\)) was slightly below that of DNN (\(0.8079 \pm 0.0193\)) and markedly below the high-specificity models XGBoost (\(0.9683 \pm 0.0421\)) and MGCN-CalRF (\(0.9544 \pm 0.0016\)), while still exceeding intermediate fusion (\(0.7323 \pm 0.0160\)). This trade-off between recall and precision yielded the highest balanced accuracy for transfer learning at approximately 0.7928, edging out intermediate fusion (0.7868) and considerably higher than DNN (0.7665), MGCN-CalRF (0.6620), and XGBoost (0.6309). The best transfer learning model likewise attained the top balanced accuracy of 0.7869, slightly above the best intermediate fusion (0.7814), as shown in Table 5.

All models achieved high AUC values (exceeding 0.84), with the transfer learning model’s AUC of \(0.8700 \pm 0.0009\) on par with XGBoost (\(0.8730 \pm 0.0015\)) and higher than those of intermediate fusion (\(0.8658 \pm 0.0035\)) and DNN (\(0.8442 \pm 0.0045\)).In terms of the F1 score (harmonic mean of precision and recall), the transfer learning model obtained \(0.3162 \pm 0.0284\), comparable to DNN (\(0.3130 \pm 0.0135\)) and slightly above intermediate fusion (\(0.2851 \pm 0.0089\)) and XGBoost (\(0.2916 \pm 0.1025\)), but lower than MGCN-CalRF (\(0.3585 \pm 0.0109\)). However, the recall-oriented F2 score of transfer learning (\(0.4958 \pm 0.0223\)) was higher than all baselines, exceeding DNN (\(0.4745 \pm 0.0104\)) and intermediate fusion (\(0.4723 \pm 0.0083\)) by approximately 2.2 points and dramatically outperforming MGCN-CalRF (\(0.3651 \pm 0.0122\)) and XGBoost (\(0.2799 \pm 0.1666\)). Notably, even in the single best model comparison, the transfer learning approach yielded the highest F2 (0.4684), essentially tied with the best intermediate fusion (0.4677) and slightly above the best DNN (0.4618), underscoring its strength in recall-sensitive performance (Table 5).

Overall, these results indicate that the proposed transfer learning model provides the best balance of sensitivity and specificity, as reflected in the highest balanced accuracy, with substantially improved recall (sensitivity and F2) while maintaining competitive specificity, precision, and AUC. Figure 6 and Supplementary Tables S7 and S8 illustrate the performance distributions over 100 iterations, highlighting the consistently superior and more stable performance of the transfer learning model compared to the baselines.

Performance distributions across 100 independent runs for five model architectures−XGBoost, plain DNN, intermediate fusion (IF), the graph-based MGCN-CalRF model (GCN), and our transfer-learning approach (TL)−evaluated on the (A) validation and (B) test sets. Each box-and-whisker plot displays the spread of (left to right) \(\hbox {F}_1\)-score, \(\hbox {F}_2\)-score, AUROC, and balanced accuracy. Horizontal brackets mark pair-wise differences quantified with two-sided paired t-tests (ns = not significant; * \(p<0.05\); ** \(p<0.01\); *** \(p<0.001\); **** \(p<0.0001\)).

Comparison with previous studies

Lastly, we compared our model’s performance with results reported in prior T2DM prediction studies. Table 6 summarizes the ranges of sensitivity, specificity, balanced accuracy, and AUC from several earlier models (using approaches such as logistic regression, SVM, ANN, random forest, linear regression, and Lasso on clinical and/or genetic data) alongside the outcomes of our proposed transfer learning model. The previously reported sensitivities ranged from about 0.5860 to 0.7590, with specificities from 0.5310 to 0.7800; balanced accuracy ranged from 0.5585 to 0.7695, and AUC from 0.7000 to 0.8450. In comparison, our transfer learning model achieved a sensitivity of 0.9023, specificity of 0.7242, balanced accuracy of 0.8132, and AUC of 0.9022 on the validation set. On the independent test set, it obtained 0.8546 sensitivity, 0.7192 specificity, 0.7869 balanced accuracy, and 0.8715 AUC.

Discussion

Our preliminary transfer learning results did not show a statistically significant average improvement over training from scratch, but they provided valuable insights into the potential of knowledge transfer between cohorts of different sizes. We observed that the best-performing single model (in terms of AUC) came from the transfer learning approach, even though the overall average performances were similar (Table 3). This suggests that pre-training on a larger cohort can provide a beneficial initialization under certain conditions. In the medical domain, where large well-annotated datasets are difficult to obtain, this finding is noteworthy. Many healthcare institutions have their own patient records, but these individual datasets are often limited in size, constraining the development of robust predictive models. Our observations align with the broader transfer learning literature: even when average improvements are modest, transfer learning typically does not harm performance and can offer advantages in specific cases. This opens up opportunities for future research to identify the conditions under which transfer learning from larger cohorts yields the most benefit, such as exploring alternative pre-training strategies or examining how dataset characteristics influence transfer effectiveness.

Building on these insights, we conducted a more robust evaluation of our methods. The 100-iteration analysis of class imbalance strategies (presented in Fig. 5) confirmed that applying either pw_BCE or WRS substantially improves model performance on imbalanced data compared to using a standard unweighted loss. Notably, the combined pw_BCE + WRS approach yielded only a marginal improvement over using WRS alone. A statistical comparison showed no significant difference between the WRS-only and combined approach in terms of balanced accuracy or AUC (p > 0.05), although the combined method had a slightly higher average. This suggests that both strategies are highly effective individually, and their combination offers limited additional benefit on our dataset. It is possible that as model architectures become more complex or training data increases, this small performance gap could widen, but in our current framework the simpler approach (using WRS alone) was nearly as good as the combined strategy. Finally, we evaluated SMOTE-NC, a data-level oversampling technique designed for mixed data types, but it yielded an extremely low sensitivity (0.21) despite achieving a high specificity, resulting in a comparatively low balanced accuracy (0.59; Table 4). This outcome indicates that synthetic oversampling may not be optimal when the minority class exhibits a complex, non-linear distribution or when interactions among categorical features are not well captured.

Across the 100 independent data splits, the four model architectures exhibited clearly differentiated performance profiles (Fig. 6). Our transfer learning model (our approach) achieved the highest median values for every clinically relevant metric−including \(\hbox {F}_1\)-score, \(\hbox {F}_2\)-score, AUC, and balanced accuracy−on both the validation set (panel A) and the independent test set (panel B). Intermediate fusion produced modest but consistent gains over the basic DNN, whereas XGBoost showed an extreme trade-off: it optimized specificity and therefore AUC, yet suffered from markedly low sensitivity, yielding the lowest F-metrics overall. Pair-wise two-sided t-tests confirmed that the transfer-learning model outperformed the DNN and intermediate-fusion models in terms of balanced accuracy and AUC (p,<,0.001, denoted ****), while the difference between the DNN and intermediate-fusion models was not statistically significant for \(\hbox {F}_1\) and \(\hbox {F}_2\) (labelled ns). Importantly, all neural-network variants significantly surpassed XGBoost in recall-oriented metrics (\(\hbox {F}_2\): p,<,0.0001). These findings underscore that (i) disentangling modality-specific feature learning through intermediate fusion is beneficial, and (ii) pre-training the clinical branch on an external cohort confers an additional, statistically significant advantage−ultimately making our transfer learning model the most robust architecture in our study. Even MGCN-CalRF, a recently proposed GCN-based method for multimodal data integration26, underperformed in comparison to our transfer learning model. It attained a much lower balanced accuracy and recall, further highlighting the robustness of our fusion and transfer learning scheme.

We also compared our model’s performance with those reported in previous T2DM prediction studies. These prior studies (using methods such as logistic regression, SVM, ANN, random forest, and others on various clinical or genetic datasets) reported sensitivities up to roughly 0.75 and AUC values up to about 0.84. In our case, the transfer learning model attained substantially higher metrics (for example, AUC 0.9022 on validation; see Table 6), indicating a marked improvement over the state-of-the-art. In particular, our framework achieved both higher sensitivity and higher AUC than any of the previously reported models. These results indicate that our transfer learning approach outperforms the earlier models in terms of identifying future T2DM cases, demonstrating its effectiveness in improving prediction performance (Table 6).

Despite its strong predictive performance, our study has two main limitations. First, transfer learning was applied only to the clinical branch; extending pre-training to genetic features could further improve accuracy. Second, the inherent class imbalance made reliable sensitivity estimation challenging. We therefore adopted a dual strategy−a positively weighted binary cross-entropy loss (pw_BCE) and a weighted random sampler (WRS)−which successfully raised sensitivity and \(\hbox {F}_2\) scores, but yielded modest \(\hbox {F}_1\) scores (\(\sim\)0.3–0.4) because of lower precision in the negative class. In a screening context such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), this trade-off is acceptable: false-positive follow-up tests are less costly than missed cases. Indeed, Dallo et al. emphasized that high true-positive rates and negative predictive values are preferable when ruling out disease risk32. Our sensitivity-oriented optimization aligns with that principle, though it may be sub-optimal for diseases (e.g. certain cancers) where false positives carry higher clinical or economic cost. Future modelling work should calibrate sensitivity-precision balance to specific disease contexts.

Conclusions

In summary, we developed and validated a novel transfer learning framework that predicts the onset of T2DM within a five-year period using Korean electronic health records. Our approach effectively addresses two key challenges in predictive modeling: the limited availability of paired multi-modal data and class imbalance in the dataset. By leveraging unpaired clinical data through transfer learning and employing robust strategies to handle class imbalance, the framework achieved strong predictive performance (test AUC 0.8715).

The success of this approach−particularly in scenarios with scarce paired data−lays a promising foundation for future T2DM prediction models. Beyond this specific application, the framework could be adapted to other disease prediction tasks and expanded to incorporate additional data modalities. Our findings represent a significant step toward more accurate and practical T2DM risk assessment in clinical settings.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality and ethical restrictions set by the Korea University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (KU-IRB-2020AS0124). However, de-identified data may be made available from the corresponding author, Prof. TaeJin Ahn, at taejin.ahn@handong.edu, upon reasonable request and with IRB approval.

References

Bae, J. H. et al. Diabetes fact sheet in Korea 2021. Diabetes Metab. J. 46, 417–426 (2022).

Tuomilehto, J. et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1343–1350 (2001).

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 393–403 (2002).

Joshi, R. D. & Dhakal, C. K. Predicting type 2 diabetes using logistic regression and machine learning approaches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 7346 (2021).

IDF Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Global Guideline for Type 2 diabetes: Recommendations for standard, comprehensive, and minimal care. Diabet. Med. 23, 579–593 (2006).

Groop, L. et al. Metabolic consequences of a family history of NIDDM (the Botnia study): Evidence for sex-specific parental effects. Diabetes 45, 1585–1593 (1996).

Kwak, S. H. & Park, K. S. Recent progress in genetic and epigenetic research on type 2 diabetes. Exp. Mol. Med. 48, e220 (2016).

Deo, R. C. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation 132, 1920–1930 (2015).

Dwivedi, A. K. Analysis of computational intelligence techniques for diabetes mellitus prediction. Neural Comput. Appl. 30, 3837–3845 (2018).

Mani S, et al. Type 2 diabetes risk forecasting from EMR data using machine learning. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, Vol. 606 (2012).

Hahn, S. J., Kim, S., Choi, Y. S., Lee, J. & Kang, J. Prediction of type 2 diabetes using genome-wide polygenic risk score and metabolomic profiles: A machine learning analysis of a population-based 10-year prospective cohort study. EBioMedicine 86, 10431 (2022).

Lee, M., Park, T., Shin, J. Y. & Park, M. A comprehensive multi-task deep learning approach for predicting metabolic syndrome with genetic, nutritional, and clinical data. Sci. Rep. 14, 17851 (2024).

Lim, H., Kim, G. & Choi, J. H. Advancing diabetes prediction with a progressive self-transfer learning framework for discrete time series data. Sci. Rep. 13, 21044 (2023).

Rönn, T. et al. Predicting type 2 diabetes via machine learning integration of multiple omics from human pancreatic islets. Sci. Rep. 14, 14637 (2024).

Nguyen, B. P. et al. Predicting the onset of type 2 diabetes using wide and deep learning with electronic health records. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 182, 105055 (2019).

Kim, J. et al. Monitoring individualized glucose levels predicts risk for bradycardia in type 2 diabetes patients with chronic kidney disease: A pilot study. Sci. Rep. 14, 30290 (2024).

Lee, H. et al. Large language multimodal models for new-onset type 2 diabetes prediction using five-year cohort electronic health records. Sci. Rep. 14, 20774 (2024).

Luo, S. & Zhao C. Transfer and incremental learning method for blood glucose prediction of new subjects with type 1 diabetes. In Proceedings of 12th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), 73–78 (2019).

Yu, X. et al. Deep transfer learning: A novel glucose prediction framework for new subjects with type 2 diabetes. Complex Intell. Syst. 7, 741–751 (2021).

Araf, I. et al. Cost-sensitive learning for imbalanced medical data: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 80 (2024).

Fernandes, E. R. Q., de Carvalho, A. C. P. L. F. & Yao, X. Ensemble of classifiers based on multiobjective genetic sampling for imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 32, 1104–1115 (2019).

Jeon, J. Y. et al. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes according to fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c. Diabetes Metab. J. 37, 349–358 (2013).

Efraimidis, P. S. & Spirakis, P. G. Weighted random sampling. In Encyclopedia of Algorithms, 1024–1027 (2008).

Binary Cross Entropy with positive weight (BCEWithLogitsLoss). PyTorch Documentation. https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/_modules/torch/nn/modules/loss.html#BCEWithLogitsLoss (2019).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O. & Kegelmeyer, W. P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Palmal, S. et al. Integrative prognostic modeling for breast cancer: Unveiling optimal multimodal combinations using graph convolutional networks and calibrated random forest. Appl. Soft Comput. 154, 111379 (2024).

Sulaiman, N. S. et al. Diabetes risk score in the United Arab Emirates: A screening tool for the early detection of type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 6, e000489 (2018).

Yu, W., Liu, T., Valdez, R., Gwinn, M. & Khoury, M. J. Application of support vector machine modeling for prediction of common diseases: The case of diabetes and pre-diabetes. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 10, 5 (2010).

Zhang, L. et al. Machine learning for characterizing risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a rural Chinese population: The Henan Rural Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 10, 4406 (2020).

Huang, X. et al. Early prediction for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes using the genetic risk score and oxidative stress score. Antioxidants (Basel) 11, 1196 (2022).

Shigemizu, D. et al. Construction of risk prediction models using GWAS data and its application to a type 2 diabetes prospective cohort. PLoS ONE 9, e92549 (2014).

Dallo, F. J. & Weller, S. C. Effectiveness of diabetes mellitus screening recommendations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 10574–10579 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a National IT Industry Promotion Agency (NIPA) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (No. S0252-21-1001, Development of AI Precision Medical Solution [Doctor Answer 2.0]). It was also supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant Number HI23C0679).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J., E.K., and S.H. performed data preprocessing and modeling experiments. M.K., S.P., and N.K. provided clinical expertise and data interpretation. Y.J. and T.A. contributed to genetic data analysis. T.A. and N.K. conceived the study and supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Korea University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (KU-IRB-2020AS0124).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, Y., Han, S., Kang, E. et al. Transfer learning prediction of type 2 diabetes with unpaired clinical and genetic data. Sci Rep 15, 27695 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05532-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05532-w

This article is cited by

-

Leveraging XGBoost and explainable AI for accurate prediction of type 2 diabetes

BMC Public Health (2025)