Abstract

Incisional hernias are common complications following abdominal surgeries. This study aimed to develop a reproducible murine model of complex incisional hernia to better understand this condition and evaluate new therapeutic strategies. Fourteen male Wistar rats underwent laparotomy to induce hernia formation. Intra-abdominal volume was measured. Hernia recurrence, tissue healing, and adhesion formation were evaluated through macroscopic and histopathological analysis, assessing fibrosis, angiogenesis, inflammation, and necrosis. All rats developed incisional hernias after laparotomy, with a 90% recurrence rate observed one week post-repair. The average hernia defect size was 10.30 mm ± 9.32 mm. A significant 25.63% reduction in intra-abdominal volume was recorded. Macroscopic examination revealed adhesions in 80% of the animals, with 60% classified as severe. Histopathological analysis showed fibrosis in all animals, with 70% displaying moderate to severe fibrosis, characterized by multifocal areas of recent fibrosis or signs of myofibroblastic differentiation. Inflammation, indicated by granulation tissue, was present in all animals. Necrosis was observed in 60% of the animals. Fibrosis affected 40% of the incision areas and 70% of the abdominal muscles. This animal model has proven versatile, reproducible, and reliable, making it suitable for investigating complex incisional hernias in translational studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hernia can be defined as an abnormal protrusion of an organ or tissue through a defect in the adjacent abdominal wall1. They are commonly found in the abdominal wall in the anatomical weakness of the muscular wall2 and are a common postoperative complication. Incisional hernia repair has a recurrence rate of up to 64% within ten years3.

Complex hernias are closely associated with visceral loss of domain and are associated with complications and high recurrence rates. In this context, some challenging conditions, such as wall closure after peritoniostomy4, gastroschisis5, or multivisceral transplant6, can be considered complex wall defects due to their high potential impact on the physiological mechanisms.

Given the high rates of recurrence, morbidity, and economic burden associated with hernia recurrences, it is essential to explore and evaluate diverse strategies for their repair. However, there is considerable variability in the approaches used in hernia surgery studies7,8,9,10,11,12,13, indicating a significant lack of standardization in this field of research. This diversity in methodologies can influence the interpretation and applicability of findings, underscoring the need for more standardized and comparable research protocols to advance the understanding of incisional hernia treatment.

To address this gap, we developed a reproducible murine model for complex incisional hernias using male Wistar rats. This model aims to mimic human pathophysiological conditions and provides a platform for studying hernia formation and recurrence mechanisms. The model’s ability to replicate both the anatomical and physiological characteristics of human hernias makes it a valuable tool for testing new surgical and therapeutic approaches, ultimately aiming to reduce recurrence rates and improve patient outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design and ethical approval

This study adopted a descriptive approach, and it was conducted at the Liver Transplantation and Experimental Surgery Laboratory, University of São Paulo. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (CEUA) under protocol number 1782/2022. All procedures followed international guidelines for animal research to minimize pain and distress. The ARRIVE protocol was followed to conduct this study14.

Animal model preparation

The Wistar rats used in this study were procured from the Animal Research Facility at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences (ICB), University of São Paulo. Upon arrival, the animals were housed in individually ventilated cages under controlled environmental conditions, including a 12-hour light/dark cycle, a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C, and relative humidity maintained between 50 and 60%.

Throughout the study, the rats had ad libitum access to standard laboratory chow and water. To ensure minimal stress and physiological stabilization before the commencement of experimental procedures, the animals underwent a one-week acclimatization period. During this time, their health and well-being were closely monitored daily for signs of stress, illness, or abnormal behavior.

All housing and experimental procedures strictly adhered to international guidelines for laboratory animal care, as outlined in the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Additionally, ethical compliance was ensured by obtaining approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (CEUA) under protocol number 1782/2022.

Fourteen male isogenic Wistar rats, aged 3–4 months and weighing between 250 and 300 g, were selected for this study. Prior to surgery, the rats were acclimatized under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with unrestricted access to food and water. They were fasted for four hours before the surgical procedures. Anesthesia was induced via an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Following the confirmation of adequate anesthesia, the animals were placed in a supine position, and the surgical site was shaved and sterilized using a 0.3% chlorhexidine solution.

Surgical procedure

A two-step surgical approach was chosen to mimic the clinical scenario where hernias form after initial surgery and later require repair. Although this increases surgical burden on the animals, careful anesthetic and post-operative management ensured survival. This model aligns with real-world patient conditions, where hernias develop over time before requiring intervention.

A standardized midline laparotomy was performed under sterile conditions, extending from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis. The fascial layer was deliberately left unsutured to induce hernia formation. This method allowed for the controlled creation of an abdominal wall defect, simulating the conditions that lead to incisional hernias in clinical practice. Postoperatively, the rats were placed in a recovery chamber and then housed individually with free access to standard feed and water. Pain management was continued as needed.

A strict postoperative care protocol was implemented to ensure optimal recovery and minimize stress-related complications, with the direct supervision of veterinarians and biomedical professionals to monitor animal health and welfare throughout the study. After surgery, each rat was housed individually in ventilated cages to prevent aggressive behavior and to facilitate close monitoring of food and water intake. The cages were kept under the same standardized environmental conditions, ensuring a stable and stress-free recovery environment.

To maintain hygiene and reduce the risk of postoperative infections, all cages were cleaned and sanitized daily, with bedding fully replaced every 48 h or immediately if soiled. This protocol created a sterile environment conducive to wound healing while minimizing the likelihood of complications such as infections or self-inflicted wound trauma.

Pain management was carefully addressed through an analgesic regimen, which included intramuscular administration of tramadol hydrochloride (15 mg/kg) and dipyrone (500 mg/kg) every 12 h, along with subcutaneous administration of ketoprofen (10 mg/kg) every 24 h. These measures were designed to alleviate postoperative discomfort and promote recovery, and their implementation was overseen by veterinarians to ensure adherence to best practices in animal welfare.

Despite these precautions, three animals succumbed to anesthetic complications and one death occurred due to a fatal vascular injury during surgery. To mitigate such risks in future studies, refinements to anesthetic protocols will be introduced, including adjustments to dosing, the use of isoflurane, and perioperative hydration strategies. Furthermore, enhanced microsurgical training for researchers, alongside continued oversight by veterinarians and biomedical professionals, will be implemented to improve procedural accuracy and further minimize risks.

Measurement of intra-abdominal pressure

Increased intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) is a critical factor in the recurrence of incisional hernias and is associated with complications such as compartment syndrome and cardiopulmonary issues. Direct measurement of IAP in animal models poses significant challenges; therefore, this study utilized an indirect method to assess intra-abdominal pressure. We adapted the needle manometry technique initially described by Whitesides et al.15 and refined it in more recent studies by Kwon et al., 202110 to ensure precise IAP measurements under controlled conditions.

Five weeks after the initial surgical intervention, the animals were re-anesthetized using the same anesthesia protocol and surgical preparation as in the initial surgery. A 1 cm skin incision was made to allow the insertion of a catheter, which was then secured with 3 − 0 cotton suture material. A three-way stopcock was attached to a 20 ml syringe filled with warmed sterile saline solution, accompanied by two extension tubes. One tube was inserted into the catheter in the abdominal wall, and the other was connected to an analog manometer.

To begin the IAP assessment, 60 ml of warmed saline solution was injected to prevent animal hypothermia. Following this, the air was carefully injected until the manometer indicated a pressure of 5 mmHg, establishing a column of free air between the saline and the end of the syringe (Fig. 1). The volume required to achieve the five mmHg pressure mark was meticulously recorded.

After measuring the IAP, the hernia defect was closed by performing a continuous suture of the aponeurosis with 3 − 0 polypropylene sutures, maintaining a 3 mm spacing between each stitch. The skin was then sutured using a continuous stitch with 3 − 0 Nylon.

The animals were closely monitored after the surgical procedure to detect any immediate postoperative complications. Standard postoperative care was provided, including maintaining a clean environment, ensuring adequate hydration and nutrition, and administering pain management as necessary.

Outcome analysis

Seven days after herniorrhaphy, the animals were re-anesthetized according to the established protocol. The intra-abdominal pressure measurement was repeated using the modified Whitesides technique to assess any changes in pressure that might indicate hernia recurrence.

Hernia recurrence

Post-euthanasia, a detailed surgical examination was performed to evaluate the recurrence of incisional hernias. The surgical site was carefully inspected for any signs of hernia recurrence, defined as any defect in the abdominal wall larger than 5 mm, regardless of the presence of a bulge at the postoperative scar site. If a hernia was detected, its length (craniocaudal) and width (transverse) were measured at the widest point.

An excision of the abdominal wall was performed to include the entire wound area in depth, encompassing the skin margins, surrounding fascia, and underlying tissues. This comprehensive excision allowed for a detailed examination of tissue healing and identification of any changes associated with hernia recurrence.

Macroscopical adhesion analysis

For macroscopic analysis of adhesions, a grading scale from 0 to 5, as described by Lien et al., as demonstrated in Table 1, was used, where a score of 5 indicates the formation of firm and dense adhesions16. The detailed scoring criteria, along with the corresponding results, are provided in Table 2.

Histopathological analysis

Following macroscopic evaluation, longitudinal and transverse cuts were made along the suture area, including all layers of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, myofascial tissues, and any adjacent structures adhered to the incision. The sections were stored in histological cassettes with 70% alcohol for 48 h, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin for subsequent blocking. The excised abdominal wall was then fixed in 10% formaldehyde for 24–48 h.

The sections were evaluated using hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining to assess the presence and extent of fibrosis and to evaluate tissue regeneration and wound healing maturation. Masson’s trichrome (MT) special staining was used to characterize and differentiate various connective tissues and soft tissue components, where smooth muscle and keratin are stained pink to red, and collagen fibers are stained blue.

A scoring system was employed to quantify the area occupied by fibrous tissue in the MT-stained sections based on the amount and distribution of collagen fibers, which are indicative of fibrosis (formation of reparative myofibroblastic tissue). The scores were assigned as follows: (0) Absent; (1+) Focal recent fibrosis; (2+) Multifocal recent fibrosis (moderate blue staining); (3+) Extensive recent fibrosis or fibrosis with signs of myofibroblastic differentiation (predominant blue staining indicating extensive collagen fiber formation).

Angiogenesis was assessed by forming granulation tissue, which consists of a combination of capillaries (neovessels), fibroblasts, and extracellular matrix formed during the healing process. It was classified as: (0) Absent; (1+) Focal granulation tissue; (2+) Multifocal granulation tissue; (3+) Extensive granulation tissue associated with recent fibrosis.

The presence of inflammation was determined based on the density of the inflammatory infiltrate and was classified as: (0) Absent; (1+) Scarce; (2+) Moderate; and (3+) Marked. The presence of necrosis, defined as ischemic cell death, was determined as either absent or present based on the evidence of coagulative necrosis.

Hemorrhage was also evaluated and was defined as “present” if microscopic evidence of erythrocyte extravasation was observed or “absent” otherwise. Histopathological evaluation was performed by a pathologist who was blinded to the intervention groups.

For interpretation, slower healing/tissue regeneration processes are characterized by a predominance of earlier pathological processes (such as hemorrhage and ischemia). In comparison, faster tissue regeneration processes show a predominance of later pathological processes (such as fibrosis and angiogenesis).

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis of the data collected in the study was performed. The results were presented as means, standard deviations, absolute numbers, and percentages. The analysis included the evaluation of incisional hernia recurrence rates, intra-abdominal volume measurements, adhesion scores, and histopathological results. Mean and standard deviation were used to describe continuous variables, while categorical data were presented in absolute numbers and percentages.

Euthanasia

The animals are kept alive for 48 h postoperatively, after which they are sacrificed and undergo a second laparotomy to assess suture integrity and remove the stomach for analysis. Following data collection, the anesthetized animals are euthanized by inhalation of 5% carbon dioxide in a specialized chamber.

After euthanasia, the animals are disposed of according to the Waste Disposal Guidelines of the FMUSP-HC System, which adheres to Resolution No. 306 (December 7, 2004) of the National Health Surveillance Agency and Resolution No. 358 (April 29, 2005) of the National Environmental Council (CONAMA).

Results

A total of 14 rats underwent primary surgery to create incisional hernias. During the follow-up period, four animals did not survive. Three deaths were due to anesthetic complications, and one was due to inadvertent injury to anatomical structures during the surgical intervention.

All animals successfully developed a midline abdominal defect as planned.

Hernia recurrence

Nine rats (90%) exhibited recurrence of incisional hernias, with an average defect size of 10.30 mm ± 9.32 mm.

Intra-abdominal volume

The average intra-abdominal volume was significantly lower after hernia repair. The mean reduction in intra-abdominal volume was approximately 25.63% one week after hernia correction, corresponding to an average decrease of 41 ml ± 16.8 ml.

Prior to laparotomy, the intra-abdominal pressure measured 130 ± 10 ml. In rats that developed hernias, the intra-abdominal pressure increased significantly to 160 ± 15.6 ml. This increase was statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.002 when compared to the group measured before laparotomy. One week following herniorrhaphy, the intra-abdominal pressure decreased to 119 ± 13.9 ml. This reduction was significant when compared to the rats with hernias, with a p-value of 0.00001. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the rats after herniorrhaphy and those prior to laparotomy, with a p-value of 0.14. These findings indicate that the presence of a hernia leads to an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, which is significantly reduced following herniorrhaphy, returning to levels comparable to pre-laparotomy conditions.

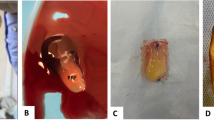

Macroscopic appearance

The macroscopic evaluation of adhesions revealed a range of adhesion severity among the 10 animals analyzed, with adhesion scores distributed across multiple grades. 20% (20%) of the animals presented no adhesions (Grade 0), while the majority exhibited varying degrees of adhesion formation. Moderate adhesions (Grade 3) were the most common, observed in 30% of the animals, followed by severe adhesions (Grade 5) and mild adhesions (Grade 2), each present in 20% of cases. Only 10% of the animals demonstrated extensive adhesions classified as Grade 4. Notably, 60% of the animals showed adhesion scores in the range of 3 to 5, indicating significant adhesion formation in a substantial portion of the sample. The detailed results are presented in Table 2.

Histopathological analysis

Histological analysis revealed that all animals developed fibrosis in the abdominal wall, with 70% exhibiting moderate to severe fibrosis, characterized by multifocal areas of recent fibrosis or signs of myofibroblastic differentiation. Rhabdomyolysis was observed in 80% of the animals, evidenced by necrosis of muscle fibers, inflammatory infiltrates, and nuclear alterations consistent with pyknosis, karyorrhexis, and karyolysis. All animals also showed signs of inflammation, as indicated by the presence of granulation tissue in the surgical area. Of these, 90% exhibited granulation tissue classified as severe or very severe, characterized by extensive areas of granulation associated with recent fibrosis. Additionally, 60% of the animals showed necrosis in the incision region. 40% demonstrated varying degrees of fibrosis in the incision area and 70% in the abdominal muscles, as depicted in Fig. 2. A summary of these results is provided in Table 2.

Photomicrographs depicting collagen-rich fibrous tissue formation in the abdominal muscle tissue of rats. Top: (1) Staining with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) shows the general histological architecture, including areas of fibrosis. (2) Masson’s Trichrome staining highlights collagen fibers in blue, demonstrating the extent of fibrosis within the muscle tissue. Bottom: Photomicrographs of H&E-stained sections. (A) Area of muscle fibrosis characterized by discontinuity in muscle bundles replaced by fibrous tissue (indicated by arrow). (B) The presence of inflammatory cells surrounding muscle bundles suggests a potential area for rhabdomyolysis.

Discussion

Due to the high recurrence rate, morbidity, and economic impact associated with incisional hernia recurrences—especially considering that the recommended treatment for these hernias is another surgical intervention—it is crucial to explore and test different methods for hernia repair. However, there is a wide variety of approaches used in hernia surgery studies, suggesting a significant lack of uniformity in this field of research. This diversity of methods can affect the interpretation and application of the results obtained, highlighting the need for more standardized and comparable research protocols to advance knowledge on treating incisional hernias.

Human studies face significant challenges, particularly due to population heterogeneity, which can introduce variability and limit the applicability and reliability of the results. Given these limitations, animal models emerge as a valuable alternative in hernia research, allowing studies that are not ethical or practical in humans, offering greater control over experimental variables (such as age and injury conditions), and being more cost-effective17. The present study identified several anatomical similarities between rats and humans (Fig. 3). Morphological studies conducted by Brown et al. also showed similar lines of action, force generation capacities, and length changes of the abdominal muscles between rats and humans throughout most of the abdominal wall, except the lower region where the external oblique muscle becomes aponeurotic in humans but remains as muscle fibers until its pelvic insertion in rats18. Functionally, the relative force generation capacities, length excursion, sarcomere lengths in the neutral position, and muscle fiber orientations are similar in both species18.

The use of rat models in hernia research is validated by their ability to mimic the pathophysiology and treatment response of hernias. Dubay et al. highlighted that fibroblast activity and collagen production peak around the fourth week of wound healing, suggesting that extending the wound maturation period in experimental studies could better reflect the chronic nature of incisional hernias observed in human patients19.

Our study introduces a reproducible rat model for both incisional and complex hernias, with all animals developing hernias and 90% exhibiting recurrence following defect closure, effectively replicating clinical conditions. Notable findings include significant adhesion formation and histopathological changes, such as moderate to severe fibrosis and rhabdomyolysis, contributing to tissue fragility and an increased risk of hernia recurrence. This descriptive study focused on the histopathological and physiological characterization of incisional hernia formation and tissue response rather than comparative analyses between experimental groups or therapeutic interventions.

The high recurrence rate and histopathological findings serves as a clinically relevant baseline, demonstrating the model’s robustness and potential as a platform for future comparative and therapeutic studies. While future research should include control and treatment groups to enable inferential statistical analyses and further validate the model, the primary goal of this study was to create a standardized experimental framework, laying the groundwork for subsequent investigations aimed at testing interventions and advancing translational research in hernia management.

To address the challenges of directly measuring intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) in animal models, an indirect method was used to assess IAP changes, demonstrating a 25.63% reduction in abdominal volume in T3 compared to T2. Measuring this difference is particularly relevant, as elevated IAP is a well-documented factor in hernia formation and recurrence, especially in conditions such as obesity and during activities like coughing20– 21. This approach also reduces the influence of outliers, as fluctuations in intra-abdominal volume can distort absolute averages. By focusing on volume differences rather than absolute values, this method enhances data reliability and offers valuable insights for future comparative studies.

This study adopted a descriptive approach, emphasizing the histopathological and physiological characterization of incisional hernia formation and tissue response rather than focusing on comparative analyses or therapeutic interventions. Since all animals underwent the same surgical protocol without distinct treatment groups, intergroup statistical comparisons were not applicable. However, descriptive statistical analyses were performed to evaluate macroscopic adhesion severity, fibrosis, and inflammatory response.

Despite the absence of a control group with fascia closure, the study successfully established a consistent and reproducible model for incisional hernias, achieving a high recurrence rate (90%). This serves as a clinically relevant baseline, demonstrating the model’s reliability and potential as a foundation for future studies involving therapeutic interventions or comparative analyses. While incorporating control and treatment groups is essential for further validation, the primary goal of this study was to develop a standardized experimental framework to guide future research efforts.

Although the sample size was limited, the study’s focus was not on comparative analyses or therapeutic evaluation but on creating a reproducible model of complex incisional hernias. By prioritizing the detailed characterization of tissue responses, the research lays a solid groundwork for subsequent studies. Expanding the sample size in future research will enhance statistical power and a more detailed and robust statistical analysis, enable comparative analyses, and explore innovative surgical and therapeutic strategies for incisional hernia repair.

While rats share similarities with humans, such as abdominal wall structure, significant differences exist, including their ability to produce an enzyme that converts l-gluconolactone to vitamin C, which is vital for collagen synthesis22. Additionally, the presence of the panniculus carnosus in rodents enables rapid wound contraction, unlike human wounds that heal through re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation23. Additionally, the quadrupedal posture of rats may recruit more abdominal muscles, potentially leading to higher intra-abdominal pressure compared to humans. The controlled laboratory conditions may not account for the variability seen in human patients, such as comorbidities and surgical techniques.

Complex hernias are widely recognized as challenging conditions, with perioperative complication rates of approximately 35.8% and mortality rates of around 3.7% in clinical settings24. Similarly, in this study, despite implementing a rigorous postoperative care protocol and direct supervision by veterinarians and biomedical professionals, four animals (29%) did not survive the follow-up period. Three deaths were attributed to anesthetic complications, likely caused by respiratory depression, and one resulted from an intraoperative vascular injury. These outcomes reflect the inherent difficulties of working with complex animal models and surgical procedures. Nonetheless, the high reproducibility of the hernia model, demonstrated by a 90% recurrence rate in surviving animals, underscores its reliability and translational potential. Future studies will aim to further reduce these risks by refining anesthetic protocols, incorporating alternatives such as isoflurane, optimizing perioperative hydration strategies, and enhancing surgical training to improve procedural accuracy and outcomes.

While this study successfully established a reproducible model for incisional hernias, we acknowledge its limitations in directly addressing the variability seen in human patients, particularly the influence of common comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, smoking, and chronic inflammation. These factors are known to significantly affect hernia formation, tissue healing, and recurrence rates in clinical settings. To enhance the translational relevance of the model, future adaptations could include incorporating experimental groups that simulate these conditions, such as diabetic or obese animal cohorts or protocols to induce systemic inflammation. These modifications would allow for a more nuanced understanding of how comorbidities impact the mechanical and biological outcomes of hernia repair, providing insights directly applicable to diverse patient populations. This approach would further strengthen the utility of the model as a platform for testing therapeutic interventions under conditions that more closely mimic human variability.

The 7-day follow-up period was selected as it represents a pivotal phase in the wound healing process, during which tissue repair is most active and key histopathological changes are prominently observed. This timeframe allowed us to capture critical findings related to fibroblast proliferation, collagen deposition, and angiogenesis, all of which are fundamental to tissue remodeling. Evidence indicates that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a crucial role in sustaining angiogenesis during granulation tissue formation up to day 725, while fibroblast activity and the production of type I and III collagen peak during this period26, contributing significantly to mechanical strength. By focusing on this specific phase, the study provided valuable insights into the cellular and molecular events underlying incisional hernia formation and recurrence. Future studies should expand on this approach by evaluating different follow-up periods, such as 7, 14, and 21 days, to better understand how tissue repair and scar formation evolve over time. Such longitudinal analyses would offer a more comprehensive perspective on the dynamics of wound healing and fibrosis, further enhancing the translational relevance of the model.

Based on the results obtained in the present study, future research could explore therapeutic interventions focusing on the component separation technique and alternative, less invasive approaches, such as laparoscopic and robotic methods for abdominal hernia repair. Additionally, further investigations into the use of progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum27 and tissue expanders as strategies to minimize tension during primary hernia closure are recommended28. These approaches can potentially improve treatment efficacy and reduce complications and recurrence rates, particularly in complex abdominal wall defects cases. Continuing this line of research could significantly contribute to the optimization of hernia repair techniques and the development of innovative therapeutic protocols.

Despite the inherent limitations of using rat models—such as differences in mechanical load and skin structure compared to humans—the similarities in wound healing processes provide valuable insights. These findings highlight the relevance of our model in translational research while emphasizing the need for careful consideration when applying these results to clinical settings.

Conclusion

This animal model has proven to be a versatile, reproducible, and reliable platform for investigating complex incisional hernias in translational research. While the present study focused on model development, future studies should utilize it to evaluate therapeutic interventions such as novel mesh materials, pharmacological agents, and alternative surgical techniques, with the objective of reducing recurrence rates and enhancing wound healing.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Ricciardi, B. F., Chequim, L. H., Gama, R. R. & Hassegawa, L. Abdominal hernia repair with mesh surrounded by fibrous tissue – experimental study in Wistar rats. Rev. Col Bras. Cir. 39, 195–200 (2012).

Franz, M. G. The biology of hernias and the abdominal wall. Hernia 10, 462–471 (2006).

Holihan, J. L. et al. Adverse events after ventral hernia repair: the vicious cycle of complications. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 221, 478–485 (2015).

Van Geffen, H. J. & Simmermacher, R. K. Incisional hernia repair: abdominoplasty, tissue expansion, and methods of augmentation. World J. Surg. 29, 1080–1085 (2005).

Denmark, S. M. & Georgeson, K. E. Primary closure of gastroschisis: facilitation with postoperative muscle paralysis. Arch. Surg. 118, 66–68 (1983).

Galvão, F. H. et al. da, Experimental multivisceral xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. ;15:184 – 90. (2008).

Dubay, D. A., Wang, X., Kuhn, M. A., Robson, M. C. & Franz, M. G. The prevention of incisional hernia formation using a delayed-release polymer of basic fibroblast growth factor. Ann. Surg. 240, 179–186 (2004).

Bikhchandani, J. & Fitzgibbons, R. J. Jr. Repair of giant ventral hernias. Adv. Surg. 47, 1–27 (2013).

Ramirez, O. M., Ruas, E. & Dellon, A. L. Components separation method for closure of abdominal-wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 86, 519–526 (1990).

Kwon, J. G. & Kim, E. K. Effects of botulinum toxin A on an incisional hernia reconstruction in a rat model. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 147, 1331–1341 (2021).

Kolygin, A. V., Vyborny, M. I. & Petrov, D. I. Ispol’zovanie Roboticheskogo Kompleksa Da Vinci v khirurgii gryzh. Opyt kliniki [Da Vinci robotic complex in hernia repair surgery]. Khirurgiia (Mosk). 3, 14–20 (2024).

Ibarra-Hurtado, T. R., Nuño-Guzmán, C. M., Echeagaray-Herrera, J. E. & Robles-Vélez, E. De Jesús González-Jaime J. Use of botulinum toxin type A before abdominal wall hernia reconstruction. World J. Surg. 33, 2553–2556 (2009).

Patiniott, P., Stagg, B., Karatassas, A. & Maddern, G. Developing a hernia mesh tissue integration index using a Porcine model - a pilot study. Front. Surg. 7, 600195 (2020).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. BMJ Open. Sci. 4, e100115 (2020).

Whitesides, T. E. Jr, Haney, T. C., Harada, H., Holmes, H. E. & Morimoto, K. A simple method for tissue pressure determination. Arch. Surg. 110, 1311–1313 (1975).

Lien, S. C. et al. Contraction of abdominal wall muscles influences size and occurrence of incisional hernia. Surgery 158, 278–288 (2015).

Vogels, R. R. M. et al. Critical overview of all available animal models for abdominal wall hernia research. Hernia 21, 667–675 (2017).

Brown, S. H., Banuelos, K., Ward, S. R. & Lieber, R. L. Architectural and morphological assessment of rat abdominal wall muscles: comparison for use as a human model. J. Anat. 217, 196–202 (2010).

DuBay, D. A. et al. Progressive fascial wound failure impairs subsequent abdominal wall repairs: a new animal model of incisional hernia formation. Surgery 137, 463–471 (2005).

Kyoung, K. H. & Hong, S. K. A Duração Da Hipertensão intra-abdominal prevê Fortemente Os resultados Para Os Pacientes cirúrgicos críticos: Um Estudo observacional prospectivo. World J. Emerg. Surg. 10, 22 (2015).

Cobb, W. S. et al. Normal intra-abdominal pressure in healthy adults. J. Surg. Res. 129, 231–235 (2005).

Abdullahi, A., Amini-Nik, S. & Jeschke, M. G. Animal models in burn research. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 3241–3255 (2014).

Masson-Meyers, D. S. et al. Experimental models and methods for cutaneous wound healing assessment. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 101, 21–37 (2020).

Latifi, R., Samson, D. J., Gogna, S. & Joseph, B. A. Perioperative complications of complex abdominal wall reconstruction with biologic mesh: A pooled retrospective cohort analysis of 220 patients from two academic centers. Int. J. Surg. 74, 94–99 (2020).

TonnesenMG, Feng, X. & Clark, R. A. Angiogenesis in wound healing. J. Invest. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 5, 40–46 (2000).

Dubay, D. A. et al. Fascial fibroblast kinetic activity is increased during abdominal wall repair compared to dermal fibroblasts. Wound Repair. Regen. 12, 539–545 (2004).

Alam, N. N., Narang, S. K., Pathak, S., Daniels, I. R. & Smart, N. J. Methods of abdominal wall expansion for repair of incisional herniae: a systematic review. Hernia 20, 191–199 (2016).

Chmielewski, L., Lee, M. & Soltanian, H. Tissue expansion during abdominal wall reconstruction. Hernia Surg. 307, 12 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Genivaldo Silva (Zu) from LIM-37 for his technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: ETN, FT, FHFGDevelopment of methodology: ETN, FT, FHFGAcquisition of data : ETN, FT, FHFGAnalysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): MAP, LC, APG, BC, VAFAWriting, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: ETN, FT, FHFGAdministrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases): SNS, CLF, GM, MMCStudy supervision: FT, URJ, LCA, FHFG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, E.T., Tustumi, F., Pereira, M.A. et al. A reproducible rat model for predicting incisional hernia recurrence: insights for clinical translation. Sci Rep 15, 23861 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05557-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05557-1