Abstract

Elderly patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) face an elevated risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular death (CVD), yet few studies have explicitly addressed CVD as a competing risk event. Traditional survival analyses often overlook competing risks, potentially biasing prognostic estimates. This study aimed to evaluate cancer-specific survival (CSS) in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC after surgery using Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model and a random survival forest (RSF) approach, thereby improving clinical decision-making. Older patients (≥ 65 years) with stage I–III CRC between 2010 and 2015 were selected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. In addition, data from 2018–2021 in the database is extracted as an external validation set. In this study, CVD was considered as a competing risk event of CRC specific death, and Fine-gray regression analysis was used to construct the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model and a competing risk-based random survival forest (RSF) model were used to analyze postoperative cancer-specific survival (CSS) in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC as the best mechanism to obtain more precise results and help make clinical management decisions. Predictors included age, sex, race, marital status, grade, T stage, N stage, histological type, primary site, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), perineural invasion, tumor deposits, tumor size. Model performance was assessed through discrimination[C-index, area under the receiver operating curve (AUC)], accuracy[Brier score (BS)], and clinical utility[decision curve analysis (DCA)]. In addition, we also visualized the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model with a nomogram and compared it with the nomogram of the Cox model. A total of 19195 elderly (≥ 65 years) patients with stage I–III CRC who underwent primary site surgery between 2010 and 2015 were included in the study. There were 10305 deaths among all patients, including 4253 deaths specific to CRC, 2571 deaths due to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, 379 deaths due to other neoplastic diseases and 3120 deaths due to other non neoplastic diseases. The Fine-Gray subdistribution risk and RSF models we developed have good discrimination power and accuracy. The Fine-Gray subdistribution risk model:the 1-year, 3-year and 5-year C-index was 0.771, 0.775 and 0.759 in the train set, and 0.744, 0.762 and 0.753 in the internal test set . The 1-year, and 3-year C-index in the external validation set was 0.762 and 0.775.The RSF model:the 1-year, 3-year and 5-year AUC was 0.782 (95% CI 0.765, 0.798), 0.8 (95% CI 0.79, 0.811) and 0.786 (95% CI 0.776, 0.796) in the train set, and 0.754 (95% CI 0.727, 0.782), 0.786 (95% CI 0.769, 0.802) and 0.782 (95% CI 0.766, 0.797) in the internal test set. The 1-year and 3-year AUC was 0.77 (95% CI 0.749, 0.79) and 0.83 (95% CI 0.786, 0.82) in the external verification set. The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year BS was 0.053 (95% CI 0.050, 0.056), 0.104 (95% CI 0.101, 0.107) and 0.128 (95% CI 0.124, 0.132) in the train set, and 0.050 (95% CI0.044, 0.056), 0.106 (95% CI 0.098, 0.112) and 0.130 (95% CI 0.124, 0.136) in the internal test set. The 1-year and 3-year BS was 0.042 (5% CI 0.038, 0.044) and 0.085 (95% CI 0.078, 0.092) in the external verification set. The RSF model we established has good discrimination power and accuracy.The 1-year, 3-year, 5-year C-index was 0.801, 0.788 and 0.769 in the train set, and 0.744, 0.754 and 0.745 in the internal test set of the RSF model. The 1-year, and 3-year C-index in the external validation set was 0.761 and 0.771.The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year AUC was 0.792 (95% CI 0.776, 0.807), 0.813 (95% CI 0.802, 0.823) and 0.801 (95% CI 0.791, 0.811) in the train set and 0.749 (95% CI 0.721, 0.777), 0.779 (95% CI 0.762, 0.796) and 0.782 (95% CI 0.767, 0.798) in the internal test set (Fig. 6a, b). The 1-year and 3-year AUC was 0.767 (95% CI 0.747, 0.788) and 0.8 (95% CI 0.783, 0.817) in the external verification set (Fig. 7c). The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year BS was 0.053 (95% CI 0.51, 0.057), 0.105 (95% CI 0.102, 0.108) and 0.131 (95% CI 0.128, 0.134) in the train set, and 0.051 (95% CI0.45, 0.055), 0.109 (95% CI 0.102, 0.116) and 0.132 (95% CI 0.125, 0.140) in the internal test set (Fig. 7d, e). The 1-year and 3-year BS was 0.042 (95% CI 0.038, 0.045) and 0.086 (95% CI 0.082, 0.091) in the external verification set (Fig. 7f).DCA showed that models could lead to higher clinical benefits for patients. Through the nomogram we constructed, it can be calculated that the traditional Cox model overestimated the CSS of patients compared with the Fine-Gray subdistribution risk model. Based on the SEER database, the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model and the competing risk-based RSF model were used to predict CSS after CRC surgery in elderly patients, and models performed well. Incorporating competing risk events in survival analysis improves result accuracy and supports personalized clinical decision-making for elderly CRC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality in the world1,2, affecting people’s physical health and causing serious social burden. According to global cancer statistics 2022, the number of new cases of CRC worldwide is about 1.9 million, with about 904, 000 deaths3. It accounts for nearly one tenth of cancer cases and deaths, with incidence and mortality ranking third and second respectively3.According to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database (https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/.) submitted in November 2023 (1975–2021), the incidence of CRC increases with age, with a median age of diagnosis of 66 and more than half of patients diagnosed between the ages of 65–84 years. It is by far one of the most frequently diagnosed malignancies in the elderly4.

Surgery is the cornerstone treatment in stage I–III CRC patients5,6. CRC patients who undergo surgery are at risk of developing new cardiovascular disease, which is associated with reduced survival7. In a large clinical study, older adults with stage I–III CRC were found to have a substantial risk of new-onset cardiovascular and cerebrovascular death (CVD)8. Older people with CRC may have an increased risk of cardiovascular death due to age-related comorbidities, anti-cancer treatments, cardiovascular toxicity, direct cancer biological mechanisms, and their common risk factors9,10,11,12. It is necessary to consider the impact of CVD on the study results when performing survival analysis of older patients with CRC.

In the past prognostic studies on clinical patients, Cox proportional risk regression model and Kaplan–Meier survival analysis methods have been widely used to predict the survival outcome of elderly patients with CRC after surgery. With respect to traditional survival analysis, all the other events are treated as censored events that may generate bias. To analyse the event with competing events, Fine-Gray competing risk regression is a suitable method13,14.

Competing risk has emerged as an important concept in the design and reporting of geriatric oncology trials15.The Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model is also a commonly used statistical analysis method for analyzing survival data in cohort studies. Fine and Gray developed competing risk regression, which accounts for the presence of competing risk by considering the effects of predictors on the cumulative incidence function (CIF)12. At the same time that the event of interest to the subject occurs, other end events may also occur. These end events will prevent the occurrence of interested events, or reduce the probability of their occurrence, and the so-called competing risk relationship is formed among the end events, which is called the competing risk event. When there are competing risk events, the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model is more accurate and stable in predicting results. For elderly CRC patients, it is more reasonable to analyze the interference of CVD events to cancer-specific death events and predict postoperative survival.

The use of random survival forest (RSF) to address competing risks is completely non-parametric. This method can be used for selecting event-specific variables and for estimating the cumulative incidence function. This method is highly effective for both prediction and variable selection in high-dimensional problems and in settings that involve many competing risks16.

In this study, CVD was used as a competing risk event for death related to CRC. The Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model and the competing risk-based RSF model for predicting postoperative cancer-specific survival (CSS) in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC were constructed based on the SEER database. It is expected to help clinicians personalized predict the probability of CSS in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC after surgery.

Materials and methods

Study population

The data for this study were selected from the SEER database established by the National Cancer Institute.We selected the database containing 17 registries, which provided data that could support the completion of this study. In this study, SEER*Stat software (version 8.4.3) was used to extract clinical data from older patients with stage I–III CRC from 2010 to 2015. In addition, data from 2018–2021 in the database is extracted as an external validation set. This study did not require approval by the ethics committee, as well as patient consent and agreement because the data was publicly available and there was no specific personal information.

Definition of elderly

Several definitions of elderly patients exist in literature with no clear and definite criteria; generally, most of the researches consider as elderly, all the patients with more than 65 years, but significantly heterogeneity exists. Moreover, the WHO has recently published new age cut-off for elderly, 75 years. The definition of elderly could not be based only on the chronological age but should be based on several factors determining the biological age. These factors are difficultly measured and no clear and objective definitions are available. For these reasons, we decided to define “elderly” as patients with more than 65 years17,18.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients with Stage IV CRC typically have markedly heterogeneous backgrounds compared to other stages19,20,21,22. This heterogeneity may confound results. Patients with stage IV CRC were excluded from the study.

The significant clinical and pathological differences between appendicular tumors and other colorectal malignancies suggest that there may also be differences in pathogenesis, although this remains to be investigated. Mainly because appendiceal tumors are relatively rare, appendiceal tumors are usually excluded from studies of prognostic variables in CRC23. We also excluded patients with appendiceal tumors in this study.

Patients who underwent surgery were identified according to “RX Summ-Surg Prim Site(1998 +) ”, patients who did not undergo surgery (code 0), and codes 90 and 99 were considered as missing information were excluded.

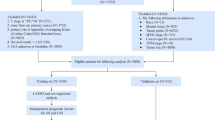

Inclusion criteria (i) Patients diagnosed with CRC between 2010 and 2015. (ii) Patients aged 65 years or older. (iii) Select colon and rectum (excluding appendix) by site code ICD-O-3. The international tumor code ICD-O-3 is C18.0, C18.2-C18.9, C19.9 and C20.9. (iv) Patients with pathologically confirmed CRC. (v) Patients with only one primary site. (vi) Patients with complete follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria (i) Survival time < 1 month. (ii) Clinical information is unknown (race, marital status, etc.). (iii) Patients who have not undergone primary site surgery (radical and local resection) and the status of surgery are unknown. (iv) The cause of death is unknown.

The external validation data were screened as above.The flowchart of inclusion and exclusion processes is shown in Fig. 1.

Variable selection and outcomes

The demographic variables, such as age at diagnosis, race, sex, and marital status, were included. Tumor characteristics consist of primary site, histologic type, T stage, N stage, grade, size, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), tumor deposits and perineural invasion.For a more intuitive and standardized study, the study data were transformed into dichotomous or multi-categorical variables. Age was classified into three age groups:65–74 years, 75–84 years and ≥ 85 years9,24; race was classified into black, white, and others (Asian or Pacific Islander; American Indian/Alaska Native); marital status was classified into married and unmarried ; histological type was classified into two categories: adenocarcinoma and others. Primary site was categorized as colon (C18.0, C18.2-C18.9) and rectum (C19.9, C20.9); tumor size was categorized as ≤ 5 cm and > 5 cm25; grade was categorized as I, II, III and IV; T stage: T1, T2, T3, T4; N stage: N0, N1, N2. Perineural invasion was classified as yes and no and CEA was classified as positive and negative. Tumor deposits were classified as yes and no.

Then, the patients were divided into four groups according to survival status and causes of death (1)alive; (2) CVD, which included diseases of heart, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension without heart disease, atherosclerosis, aortic aneurysm and dissection, and other diseases of arteries, arterioles, and capillaries26,27; (3) CRC cancer-specific death; and (4) other events , which includes other cancer deaths and other noncancer deaths. Obtained from the SEER Cause of Death Recode 1969 + (03/01/2018) (cancer.gov).

Statistical analysis

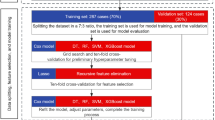

We randomly grouped the research queue at 7:3 to form a train set and a internal test set, where the train set was used to build the model and we verified the model by internal and external test set.Pearson’s coefficient and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) were used to evaluate the correlation and the co-linearity of the predictors28,29,30. Multicollinearity is determined to be present if the variance inflation factor is more than 5 to 1028,30. Two independent variables were considered highly correlated if their correlation value was > 0.729,31.

Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model and nomogram

Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard models were used to analyze the data, with CRC-specific deaths as the outcome event and CVD as the competing event. First, we performed a univariate analysis, plotting CIF curves for CRC-specific deaths and CVD, and comparing differences between groups using the Fine-Gray test. Second, variables with statistical significance (p < 0.05) were screened for inclusion in the multivariate analysis. Third, the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model was constructed by screening statistically significant variables from the multi-factor analysis in the training set, and a nomogram of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model was established to predict CSS for 1, 3, and 5 years.

Traditional Cox nomogram

We screened variables associated with CSS by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis and plotted the nomogram predicting CSS for 1, 3, and 5 years. The competing risk nomogram was compared with the traditional Cox nomogram under the same variables.

Random survival forests model for competing risks

RSF is a survival model based on the tree method for the analysis of right-censored survival data. To develop and validate the RSF, data were divided to learning (63% of data to develop the model) and test (37% of data to check the data validity) parts. Totally, 1000 bootstraps samples were constructed from the learning part. Then a competing risk tree for each bootstrap sample was grown. To split each node of a tree, a subset of p variables was selected randomly, and the node was split using the candidate variable that maximizes a competing risk splitting rule. The tree is grown to full size under the constraint that a terminal node should have no less than unique cases. Then we calculate cumulative incidence functions and cumulative cause-specific hazards for all events (Death of CRC, Death of CVD) for each tree. Eventually, take the average of each estimator over all trees to obtain its ensemble16. In RSF, variables can be selected by filtering on the basis of their variable importance (VIMP)16. The VIMP for x, a risk factor, is the prediction error for the original ensemble subtracted from the prediction error for the new ensemble obtained using randomizing x assignments. A large positive VIMP indicates a potentially predictive variable whereas zero or negative values identify non-predictive variables to be filtered16.

The variables selected were used to construct the RSF model and the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model. And the importance of the predictors was assessed. Adjust both mtry and nodesize hyperparameters using the tune.rfsrc function in randomForestSRC.After adjusting the hyperparameters, we use the optimal hyperparameters to build the final model in the training set. RSF models can also plot CIF curves for CRC-specific deaths and CVDs.

Model evaluation

The effectiveness of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model and RSF model was evaluated from three aspects: accuracy, calibration and clinical benefit. Ten-fold cross validation was used to verify the model constructed by the validation set against the training set to ensure the stability of the model.Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to estimate models discrimination by calculating the C-statistic or area under the curve (AUC).We also assessed the performance of each prediction model to discriminate outcomes on the test dataset using Harrell’s concordance index (C-index)32. The AUC and C-index ranged from 0 to 1, and the closer to 1 the more accurate the model was. We used the Brier score (BS) (mean squared distance between the predicted probabilities and actual outcomes) to predict the accuracy of each model33. BS range from 0 to 1.00, with 0 representing the best possible calibration33. Higher AUC/C-index and lower BS indicate better prediction performance. In addition, decision curve analysis (DCA) curve was used to evaluate the clinical benefit of the model to reflect whether the model could benefit patients by affecting clinical decision-making. After obtaining the threshold, the decision curve was used to determine whether the net benefit corresponding to the threshold on the None line and the All line below the threshold was higher than the net benefit value. If it is higher than that, it indicates that the model has clinical utility.

The R software (version 4.4.2; http://www.r-project.org/) was used for all statistical analyses. The “cmprsk”, “riskRegression”, and “prodlim” packages were used for competing risk analysis, the “mstate", “regplot” packages for plotting competing risk nomogram. We performed Cox regression analysis using the “survival” package and plotted the traditional Cox nomogram using the “regplot” package. The “randomForestSRC” package was used for construct the RSF model. Statistical significance was defined as a two-side p value < 0.05.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

A total of 19195 elderly patients with stage I–III CRC who underwent primary site surgery between 2010 and 2015 were included in the study. There were 10305 deaths among all patients, including 4253 deaths specific to CRC, 2571 deaths due to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, 379 deaths due to other neoplastic diseases and 3120 deaths due to other non neoplastic diseases. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were white in race (81.2%), and the most common histological type was adenocarcinoma (89.7%). Most patients’ tumors are moderately differentiated (72.7%). There were more patients in T3 stage (58.6%) and N0 stage (62.2%). Most of the patients had negative perineural invasion (90.3%), negative tumor deposits (90.2%). 81.3% of the patients had tumors in the colon, 18.7% of the patients had tumors in the rectum, and most of the patients had tumors < 5 cm (58.7%).

All the correlation coefficients between pairs of variables were < 0.7 and the VIF values were < 5, indicating no collinearity among the independent variables (Fig. 2).

Fine‑Gray test and Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model

First, we used Fine-Gray test to plot the CIF (Fig. 3). The outcome indicated that age, race, marital status, primary site, T stage, N stage, grade, histological type, perineural invasion, CEA, tumor size, tumor deposits were associated with postoperative CSS in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC. The risk factors associated with CVD were age, race, marital status, primary site, tumor grade, T stage, N stage, CEA, tumor deposits and perineural invasion.

Second, we included univariate statistically significant variables in the multivariate competing risk analysis. The outcome indicated age, race, marital status, primary site, T stage, N stage, grade, perineural invasion, CEA and tumor deposits were independent prognostic factors of postoperative CSS in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC (Table 2).

Third, we used independent prognostic factors to construct the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model in the train set. Then evaluate the performance of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model. In addition, the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model was visualized and the nomogram was finally plotted (Fig. 5a).

The model evaluation of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model constructed based on univariate to multivariate screening is shown in Fig. 3. The Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model we established has good discrimination power and accuracy. The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year C-index was 0.771, 0.775 and 0.759 in the train set, and 0.744, 0.762 and 0.753 in the internal test set. The 1-year, and 3-year C-index in the external validation set was 0.762 and 0.775.The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year AUC was 0.782 (95% CI 0.765, 0.798), 0.8 (95% CI 0.79, 0.811) and 0.786 (95% CI 0.776, 0.796) in the train set, and 0.754 (95% CI 0.727, 0.782), 0.786 (95% CI 0.769, 0.802) and 0.782 (95% CI 0.766, 0.797) in the internal test set (Fig. 4a, b). The 1-year and 3-year AUC was 0.77 (95% CI 0.749, 0.79) and 0.83 (95% CI 0.786, 0.82) in the external verification set (Fig. 4c). The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year BS was 0.053 (95% CI 0.050, 0.056), 0.104 (95% CI 0.101, 0.107) and 0.128 (95% CI 0.124, 0.132) in the train set, and 0.050 (95% CI0.044, 0.056), 0.106 (95% CI 0.098, 0.112) and 0.130 (95% CI 0.124, 0.136) in the internal test set (Fig. 4d, e). The 1-year and 3-year BS was 0.042 (5% CI 0.038, 0.044) and 0.085 (95% CI 0.078, 0.092) in the external verification set (Fig. 4f). Decision curve (median survival time) shows that this model leads to higher clinical benefits for patients (Fig. 4 g, h, i). The DCA indicated that when thethreshold probabilitiesranged between 10 and 40%, 15% and 70%, 20% and 75%, the use of the nomogram to predict 1-year CSS, 3-year CSS and 5-year provided greater netbenefit than the “all” or “none” strategies, which indicates the clinical usefulness of the nomogram.

(a) ROC curve and AUC for 1, 3, and 5 years of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model in the train set. (b) ROC curve and AUC for 1, 3, and 5 years of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model in the internal test set. (c) ROC curve and AUC for 1 and 3 years of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model in the external test set (d) Birer score curve of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model in the train set. (e) Birer score curve of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model in the internal test set. (f) Birer score curve of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model in the external test set. (g) Decision curve for 1 year of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model. (h) Decision curve for 3 years of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model. (i) Decision curve for 5 years of the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model.

Competing risk nomogram vs. traditional Cox nomogram

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to explore the factors affecting CSS in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC after operation (Table 3). The results showed that age, race, marital status, grade, primary site, T stage, N stage, CEA, perineural invasion, tumor deposits were independent prognostic factors of postoperative CSS in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC. We created a traditional Cox nomogram in the train set (Fig. 5b).

In addition, different values for each variable were taken to obtain different values of scores, and the total scores were obtained by adding all the scores of each variable, and according to the total scores, the CSS of patients at 3 and 5 years could be predicted accordingly. For example, a patient aged 65–74 years old, white, married, female, with adenocarcinoma in the rectum, grade II, T2 stage, N0 stage, negative CEA, positive tumor deposition, no perineural invasion, and tumor size less than 5 cm. The total score in the competing risk nomogram was 159; however, it was 180 in the conventional Cox nomogram (Fig. 5a, b). For the same variables, the traditional Cox model overestimates the patient’s CSS by 1, 3, or 5 years.

Variables were screened based on competing risk data and RSF model

First, RSF was used to screen variables based on competing risk data using VIMP method. As shown in Fig. 6a, the importance of variables was ranked. According to the importance of RSF variables, N stage, T stage, tumor deposits, age and CEA were the five most important variables. Composite variable importance and VIMP values, we selected ten variables: age, race, primary site, tumor grade, histological type, T stage, N stage, CEA, tumor deposition, and perineural invasion.Then, it was found that when the hyperparameter ‘ntree’ was set to be 480, ‘mtry’ was set to be 7, and ‘nodesize’ was set to be 85 (Fig. 6b). The competing risk correlation graph is shown in the Fig. 6c.

Construction of the RSF model in predicting CSS after surgery in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC in the train set. (a) Prediction error rates and the VIMP plot. (b) Hyperparameter tuning for RSF c CS-CHIF:cause-sepcific cumulative hazard fuction;CIF:cumulative incidence function;CPC:continuous probability curves.

The RSF model we established has good discrimination power and accuracy.The 1-year, 3-year, 5-year C-index was 0.801, 0.788 and 0.769 in the train set, and 0.744, 0.754 and 0.745 in the internal test set of the RSF model. The 1-year, and 3-year C-index in the external validation set was 0.761 and 0.771.The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year AUC was 0.792 (95% CI 0.776, 0.807), 0.813 (95% CI 0.802, 0.823) and 0.801 (95% CI 0.791, 0.811) in the train set and 0.749 (95% CI 0.721, 0.777), 0.779 (95% CI 0.762, 0.796) and 0.782 (95% CI 0.767, 0.798) in the internal test set (Fig. 6a, b). The 1-year and 3-year AUC was 0.767 (95% CI 0.747, 0.788) and 0.8 (95% CI 0.783, 0.817) in the external verification set (Fig. 7c). The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year BS was 0.053 (95% CI 0.51, 0.057), 0.105 (95% CI 0.102, 0.108) and 0.131 (95% CI 0.128, 0.134) in the train set, and 0.051 (95% CI0.45, 0.055), 0.109 (95% CI 0.102, 0.116) and 0.132 (95% CI 0.125, 0.140) in the internal test set (Fig. 7d, e). The 1-year and 3-year BS was 0.042 (95% CI 0.038, 0.045) and 0.086 (95% CI 0.082, 0.091) in the external verification set (Fig. 7f). Decision curve (1-year, 3-year and 5-year ) shows that this model leads to higher clinical benefits for patients (Fig. 7g, h, i). The DCA indicated that when thethreshold probabilitiesranged between 10 and 50%, 15% and 80% , 20% and 80% , the use of the nomogram to predict 1-year CSS, 3-year CSS and 5-year provided greater netbenefit than the “all” or “none” strategies, which indicates the clinical usefulness of the RSF model.

(a) ROC curve and AUC for 1, 3, and 5 years of the RSF model in the train set. (b) ROC curve and AUC for 1, 3, and 5 years of the RSF model in the internal test set. (c) ROC curve and AUC for 1 and 3 years of the RSF model in the external test set. (d) Birer score curve of the RSF model in the train set. (e) Birer score curve of the RSF model in the internal test set. (f) Birer score curve of the RSF model in the external test set. (g) Decision curve for median survival time (1 year) of the RSF model in the train set. (h) Decision curve for median survival time (3 years) of the RSF model in the train set. (i) Decision curve for median survival time (5 years) of the RSF model in the train set. (j) Brier score curves of the RSF model.

Discussion

This study highlights the critical role of competing risk adjustment in survival analyses for elderly CRC patients. The Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model is more suitable for prognostic estimation because competing risks are taken into account.In this study, we aimed to analyze CSS in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC based on the SEER database. CVD death was considered a competing event. Although many previous studies on survival analyses for patients with stage I–III CRC have been performed, most of the previous studies analysed overall survival by treating all outcomes as one, which might not be suitable to identify CRC patients with different risks of various outcomes34,35. In previous studies, patients with competing events were included as censored data, and thus the results were biased to varying degrees.While the traditional Cox model overestimated CSS by ignoring competing events, consistent with previous studies36,37,38, our Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model provided more accurate risk stratification. When performing a survival analysis, it is necessary to include the effect of competing risk events on the target outcome.

One study showed that high T-stage (T4), rectal high, N-stage (N2), elevated CEA, poor tumor differentiation, and age at diagnosis were all individual poor prognostic factors for postoperative cancer-specific survival in stage I–III CRC, which is consistent with our study39. Perineural invasion is a relatively new histopathological feature that is associated with poor clinical prognosis and reduced survival in various malignancies, including CRC40,41.In most studies, the reported incidence of Perineural invasion in CRC patients ranges between 9 and 33%41,42. Of the included cases, perineural invasion was present in 828 patients (19.5%) who died from CRC.Evaluation of perineural invasion after surgery is helpful to predict the prognosis of patients and guide further treatment options. Tumor deposits, considered an independent predictor of prognosis in CRC patients, provides important prognostic information in CRC patients and warrants further investigation as a unique variable in future CRC staging43. In an RCT of stage III colon cancer patients, being divorced/separated/widowed or living with another family was significantly associated with worse colon cancer recurrence and mortality, respectively, compared with being married or living with a spouse/partner44. This is also consistent with our study. At the same time, the RSF model can rank the importance of variables.N stage, T stage, tumor deposits, age and CEA were the five most important variables so that clinicians can more intuitively understand the indicators that have a greater impact on the outcome. Clinicians can manage high-risk populations by understanding the factors that affect the survival of elderly patients with stage I–III CRC.

In this study, Fine-Gray subdistribution risk model and competing risk-based RSF model were used to analyze postoperative CSS in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC, and the models showed good performance. The nomogram provides a simple and feasible clinical tool for individualized prediction of CSS in elderly patients with CRC, which can provide a basis for individualized postoperative management of elderly patients with CRC.With the advent of the medical big data era, machine learning models will be increasingly used in clinical practice to help improve the prognosis of patients.

In this study, due to the consideration of competing events, the prediction results were more accurate and stable than the traditional Cox model. It is also more reasonable to predict the postoperative survival of elderly patients with stage I–III CRC.

Limitation

There are several limitations existing in this study. First, our analysis quantifies the hazard risk of many variables associated with CSS of CRC, but does not take patients’.

comorbidities into account due to the limitations of SEER.Nevertheless, the results in this study are still meaningful and should be improved. Second, because the demographic and clinical information provided by the SEER database is not complete, more than 40, 000 individuals were excluded, which may lead to some selection bias.

Third, the SEER database itself is a high-quality population-based cancer registry, but there are still incomplete information, such as BMI, dietary habits, biomarkers, biochemical test information, and lifestyle (smoking and drinking). Radiotherapy and chemotherapy details were missing in the SEER database. Radiotherapy data are classified by the type of RT received or "no/unknown – no evidence of radiation was found in the medical records examined". Chemotherapy data are categorized as either "yes – patient had chemotherapy" or "no/unknown – no evidence of chemotherapy was found in the medical records examined". (https://seer.cancer.gov/data-software/documentation/seerstat/nov2023/treatment-limitations-nov2023.html).Although several limitations exist in this study, the analysis in the present study was still meaningful and can offer some information for clinical management.

Conclusions

Based on the SEER database, this study established the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model and the RSF model for postoperative survival of I–III CRC in elderly patients. The prediction performance of the models is good, and it has certain guiding significance for clinical work. The Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model is visualized in the form of nomogram. It is more convenient and intuitive to use nomogram to predict CSS in elderly patients with stage I–III CRC. The prediction models constructed with competing risk events in mind is more suitable for elderly cancer patients.

Data availability

Only publicly available data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) were used in this study, and data sources and handling of these data are described in the Materials and Methods.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- BS:

-

Brier score

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CIF:

-

Cumulative incidence function

- C-index:

-

Concordance index

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CRR:

-

Competing risk regression

- CSS:

-

Cancer-specific survival

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular death

- DCA:

-

Decision curve analysis

- K-M:

-

Kaplan-Meier

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- RSF:

-

Random survival forests

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, epidemiology and end results

References

Arnold, M. et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 66(4), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912 (2017).

Murphy, C. C. & Zaki, T. A. Changing epidemiology of colorectal cancer - birth cohort effects and emerging risk factors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-023-00841-9 (2024).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74(3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Siegel, R.L., Giaquinto, A.N., Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024[published correction appears in CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Mar-Apr;74 (2):203. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21830]. CA Cancer J Clin. 74 (1):12–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21820 (2024).

Bos, A. C. R. K. et al. Postoperative mortality in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: The impact of age, time-trends and competing risks of dying. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 45(9), 1575–1583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2019.04.0207 (2019).

Ketelaers, S. H. J., Orsini, R. G., Burger, J. W. A., Nieuwenhuijzen, G. A. P. & Rutten, H. J. T. Significant improvement in postoperative and 1-year mortality after colorectal cancer surgery in recent years. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 45(11), 2052–2058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2019.06.017 (2019).

Kim, H., Park, I. J., Han, Y., Kwon, T. W. & Cho, Y. P. Cardiovascular morbidities in postoperative colorectal cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 21359. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00735-3 (2021).

Kenzik, K. M. et al. New-onset cardiovascular morbidity in older adults with stage I to III colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 36(6), 609–616. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.74.9739 (2018).

Guan, T. et al. Long-term risks of cardiovascular death in a population-based cohort of 1, 141, 675 older patients with cancer. Age Ageing. 52(5), afad068. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afad068 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. Cardiovascular-specific mortality and risk factors in colorectal Cancer patients: A cohort study based on registry data of over 500, 000 individuals in the US. Prev. Med. 179, 107796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107796 (2024).

Kenzik, K. M. et al. New-onset cardiovascular morbidity in older adults with stage I to III colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 36(6), 609–616. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.74.973911 (2018).

Fine, J. & Gray, R. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 94, 496–509 (1999).

Berry, S. D., Ngo, L., Samelson, E. J. & Kiel, D. P. Competing risk of death: An important consideration in studies of older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 58(4), 783–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02767.x (2010).

Varadhan, R. et al. Evaluating health outcomes in the presence of competing risks: A review of statistical methods and clinical applications. Med. Care. 48(6 Suppl), S96–S105. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d99107 (2010).

Burdett, N., Vincent, A. D., O’Callaghan, M. & Kichenadasse, G. Competing risks in older patients with cancer: A systematic review of geriatric oncology trials. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110(8), 825–830. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy111 (2018).

Ishwaran, H. et al. Random survival forests for competing risks. Biostatistics 15(4), 757–773. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxu010 (2014).

Edwards, D., Carrier, J. & Hopkinson, J. Assistance at mealtimes in hospital settings and rehabilitation units for patients (>65years) from the perspective of patients, families and healthcare professionals: A mixed methods systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 69, 100–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.013 (2017).

Fugazzola, P. et al. The SIFIPAC/WSES/SICG/SIMEU guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis in the elderly (2019 edition). World J. Emerg. Surg. 15(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-020-00298-0 (2020).

Verhoef, C., de Wilt, J. H., Burger, J. W., Verheul, H. M. & Koopman, M. Surgery of the primary in stage IV colorectal cancer with unresectable metastases. Eur. J. Cancer. 47(Suppl 3), S61–S66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70148-4 (2011).

Gelsomino, F. et al. To resect or not to resect: The hamletic dilemma of primary tumor resection in patients with asymptomatic stage IV colorectal cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 132, 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.10.001 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Survival outcome of palliative primary tumor resection for colorectal cancer patients with synchronous liver and/or lung metastases: A retrospective cohort study in the SEER database by propensity score matching analysis. Int. J. Surg. 80, 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.06.02422 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Real-world analysis of survival benefit of surgery and adjuvant therapy in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 14866. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41713-1 (2023).

Compton, C., Fenoglio-Preiser, C. M., Pettigrew, N. & Fielding, L. P. American joint committee on cancer prognostic factors consensus conference: Colorectal working group. Cancer 88(7), 1739–1757 (2000).

Wallace, D. et al. Identifying patients at risk of emergency admission for colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 111(3), 577–580. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.300 (2014).

Chen, X. et al. Survival outcome of palliative primary tumor resection for colorectal cancer patients with synchronous liver and/or lung metastases: A retrospective cohort study in the SEER database by propensity score matching analysis. Int. J. Surg. 80, 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.06.024 (2020).

Fung, C. et al. Cardiovascular disease mortality after chemotherapy or surgery for testicular nonseminoma: A population-based study. J. Clin. Oncol. 33(28), 3105–3115. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.3654 (2015).

Sturgeon, K. M. et al. A population-based study of cardiovascular disease mortality risk in US cancer patients. Eur. Heart J. 40(48), 3889–3897. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz766 (2019).

Vatcheva, K. P., Lee, M., McCormick, J. B. & Rahbar, M. H. Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology (Sunnyvale). 6(2), 227. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-1165.1000227 (2016).

Hong, H., Liu, J. & Zhu, A. X. Modeling landslide susceptibility using LogitBoost alternating decision trees and forest by penalizing attributes with the bagging ensemble. Sci. Total Environ. 718, 137231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137231 (2020).

Kim, J. H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 72(6), 558–569. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.19087 (2019).

Liao, Y., Yin, G. & Fan, X. The positive lymph node ratio predicts survival in T1–4N1–3M0 non-small cell lung cancer: A nomogram using the SEER database. Front. Oncol. 10, 1356. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01356 (2020).

Harrell, F. E. Jr., Califf, R. M., Pryor, D. B., Lee, K. L. & Rosati, R. A. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA 247(18), 2543–2546 (1982).

Angraal, S. et al. Machine learning prediction of mortality and hospitalization in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 8(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2019.06.013 (2020).

Hong, N. S. et al. A survival analysis of gastric or colorectal cancer patients treated with surgery: Comparison of capital and a non-capital city. J. Prev. Med. Public Health. 50(5), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.17.043 (2017).

Yuan, Y. et al. Prognostic and survival analysis of 837 Chinese colorectal cancer patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 19(17), 2650–2659. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2650 (2013).

Schuster, N. A., Hoogendijk, E. O., Kok, A. A. L., Twisk, J. W. R. & Heymans, M. W. Ignoring competing events in the analysis of survival data may lead to biased results: A nonmathematical illustration of competing risk analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 122, 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.03.004 (2020).

Al-Wahsh, H. et al. Accounting for the Competing Risk of Death to Predict Kidney Failure in Adults With Stage 4 Chronic Kidney Disease. JAMA Netw. Open. 4(5), e219225. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.9225 (2021).

Cooper, H., Wells, S. & Mehta, S. Are competing-risk models superior to standard Cox models for predicting cardiovascular risk in older adults? Analysis of a whole-of-country primary prevention cohort aged ≥65 years. Int. J. Epidemiol. 51(2), 604–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab116 (2022).

van den Berg, I., Coebergh van den Braak, R.R.J, van Vugt, J.L.A, Ijzermans, J.N.M. Buettner, S. Actual survival after resection of primary colorectal cancer: results from a prospective multicenter study[published correction appears in World J Surg Oncol. 2021 May 26;19 (1):159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-021-02252-z.]. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19 (1):96. Published 2021 Apr 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-021-02207-4. (2021).

Cao, Y. et al. Perineural invasion is associated with poor prognosis of colorectal cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 35(6), 1067–1075. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-020-03566-2 (2020).

Knijn, N., Mogk, S. C., Teerenstra, S., Simmer, F. & Nagtegaal, I. D. Perineural invasion is a strong prognostic factor in colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000518 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Perineural invasion in colorectal cancer: Mechanisms of action and clinical relevance. Cell Oncol. (Dordr). 47(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-023-00857-y (2024).

Bhutiani, N. et al. The prognostic impact of tumor deposits in colorectal cancer: More than just N1c. Cancer 130(23), 4052–4060. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.35491 (2024).

Lee, S. et al. Marital status, living arrangement, and cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: Findings from CALGB 89803 (Alliance). Oncologist 27(6), e494–e505. https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyab070 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the SEER Registry Program for granting access to registry data for this analysis. The authors highly appreciate all the members who were involved in the present study.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X. L conceived the idea, designed the study and supervised the work. Q. Z were responsible for the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, drafting, and writing of the article. R. X,completed analyses, provided descriptive epidemiology expertise. W. Z revised the content. X. B, Z. L, Y. Z plotted the data. W.W, Z. Y advised on analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. The data from SEER is publicly available and de-identified. Ethics approval is not applicable. Consent is not requested.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Xu, R., Zhen, W. et al. Competing risk and random survival forest models for predicting survival in post-resection elderly stage I–III colorectal cancer patients. Sci Rep 15, 24269 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05824-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05824-1