Abstract

Accurately locating the weak links in chamber group is crucial for achieving targeted and directional control for its surrounding rock. In this paper, the topological structure of the chamber group was first established, which divided the chambers into important chambers and general chambers. The chain instability inertia I was defined as the ratio of important chambers m to all chambers n, which can reflect the difficulty of chain instability for chamber group. On this basis, two-chamber, three-chamber, and four-chamber group were analyzed respectively, the topological structure evolution of chamber group were revealed. The concept of structural importance was introduced, which was used to quantitatively characterize the influence of micro-state of each chamber on macro-state of chamber group. Finally, a method of key chambers identification was proposed. When I = 0, there are no key chambers; when I = 1/n, the important chamber is the key chamber; and when I > m/n, chamber with the maximum key coefficient is the key chamber. Moreover, key chambers identification should follow four principles of structure, diversity, dynamic and priority. This research established a quantitative and effective framework for the stability control of chamber group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chamber group in coal mine is a system, which composed of several chambers with specific functions. The stability control of its surrounding rock is not only a prerequisite for functional performance, but also a necessary guarantee for safety and efficiency of coal mining1,2. However, the stress environment of chamber group is very complex under the combined influence of internal structure and external disturbance. Especially in deep mining, the deformation and failure of surrounding rock are particularly severe, and chain instability occur frequently3,4.

Nowadays, many scholars have proposed a series of supporting technologies and control strategies for chamber group stability control, such as reduce interaction5, eliminate stress concentration6, improve construction methods7, optimize construction processes8, increase support strength9, and strengthen the mechanical properties of surrounding rock10. In terms of interaction reducing and stress concentration eliminating, Kang et al.11,12 pointed out that the interaction caused by excavation is the main factor of stress concentration in deep large-section chamber groups, and proposed optimization methods for chamber group layout and surrounding rock reinforcement. Zhu et al.13,14 proposed a compact layout principle and method for deep large-section chamber groups in response to the serious failure of surrounding rock. In terms of construction methods improving and construction processes optimizing, He et al.15,16 found that the construction of chamber group should follow the principle of"from small to large"by analyzing the stress and deformation of surrounding rock. Gao et al.17 applied ant-colony algorithm to underground engineering practice to optimize the construction sequence of chamber group. Huang et al.18 used numerical simulation methods to establish evaluation indicators for characterizing deformation of surrounding rock, and obtained the optimal excavation sequence of chamber group. In terms of support strength improving and surrounding rock strengthening, Wei et al.19 focused on deep soft-rock large-section chamber group, discussed the applicability of combined bolting and grouting support to high geostress and complex structural conditions. Cheng et al.20 believed that the size of the cross-section and repeated disturbance are the main reasons for instability of chamber group, and proposed a combined bolting + lining support method. Wang et al.21 found that the layout, geostress, and lithology of chamber group are the causes of asymmetric deformation, and proposed a truss + bolt net + bottom grouting pipe coupling support technology. Xin et al.22 analyzed the influence of mining depth, fault structure, and layout structure on the stability of chamber group, and proposed a"two-strength"control technology, which consisted of surrounding rock and support structure strengthening.

The above researches have provided many scientifically feasible solutions for the stability control of coal mine chamber group. However, most of the support designs are indiscriminate for all chambers, which leads to problems such as unclear support focus and unspecific control objectives. Tan et al.23,24 believed that the essence of chain instability is the concentrated manifestation of the“domino effect”, which is, a small initial changes may lead to a series of chain reactions in a system with internal connections. If a chamber occurs instability, it will generate stress and energy increment on the surrounding rock of other chambers, serving as the trigger for the chain instability of chamber group. If any other chamber become activated and unstable under the influence of this increments, it forms the first link of the chain instability. At this time, the stress and energy in the surrounding rock of the remaining stable chambers/areas will further change. If the instability continues to occur, the chain instability of chamber group will be formed. Therefore, accurately locating the weak links and applying reasonable measures have important theoretical significance and engineering value for the stability control of chamber group.

In this paper, the logical relationship dominated by chain instability of chamber group was established based on the reliability theory, and the topological structures were proposed. Then, the influence of the structural evolution characteristics on its overall stability were analyzed. And the identification methods and principles of the key chambers are obtained. This study could provide guidance and reference for the stability control of chamber group.

Topological structures of chamber group

Chain instability inertias

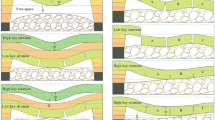

The stability of chamber groups is a complex systematic engineering problem. In order to research the overall safety of the chamber group, it is necessary to clarify the logical relationships between chamber and chamber, chamber and chamber group. The so-called chain instability of chamber groups refers to the phenomenon in which the instability of a certain chamber leads to the instability of any chamber in the group23,24. In order to effective analysis of the structural connectivity, chambers are treated as homogeneous nodes in the graph representation, and their individual physical dimensions (such as height, width, or volume) are not directly considered. Therefore, the chamber group can be regarded as a topological structure based on the reliability theory25,26. It is a block diagram to study the logical relationship between systems and units, as well as a comparison between the two basic events of “overall stability” and “chain instability”. Typical topological structures are divided into series system and parallel system. If any one unstable chamber lead to the chain instability of the entire group, this type is a series system, where the stability of all n chambers is a necessary condition for the overall stability, as shown in Fig. 1(a). If only all n chambers unstable lead to the chain instability of the entire group, this type is a parallel system, where the instability of all n chambers is a sufficient condition for the chain instability, as shown in Fig. 1(b).

Typical topological structures26.

It can be seen that the essential difference between the series and parallel systems lies in whether the instability of individual chamber will lead to the chain instability of the chamber group. In the series system, only when each chamber is stable can the chamber group maintain overall stability. On the contrary, only when all chamber are unstable can it be determined that the chamber group is instability in the parallel system. On this basis, the chamber on the series line can be called as important chamber, and the chamber on the parallel line can be called as general chamber. That is to say, only the instability of important chambers will lead to the chain instability of chamber group occur. As long as the general chambers are not all unstable, they will not affect the overall stability of the chamber group. Therefore, the state of the chamber group with important chamber can be determined as metastable state, and the state of the chamber group with only general chamber can be determined as stable state.

All chambers in the chamber group are traversed, and the important chambers and general chambers are divided. If the instability of the selected chamber leads to the instability of at least one chamber, the chamber is an important chamber, which is located in the series line. If the instability of the selected chamber does not cause the instability of any chamber, the chamber is a general chamber, which is located in a parallel line, as shown in Fig. 2. It can be seen that the more chambers on the series line, the worse the chamber group stability, and the more prone to chain instability. Therefore, the ratio of the number of chambers on the series line to the total number of chambers is defined as chain instability inertia, which is used to reflect the difficulty of chain instability for chamber group.

where I is chain instability inertia for chamber group, m is the number of chambers on the serial line; n is the total number of chambers within a certain area.

Therefore, the greater the chain instability inertia, the more important chambers there are in the chamber group. The instability of the important chamber will directly or indirectly affect other important chamber and general chamber, thus forming one or more chain instability links. The new additional stress and energy generated by chambers instability will increase exponentially. In other words, when the chain instability inertia is smaller, it indicates that the general chambers dominant, the instability of general chambers will not affect the overall stability of chamber group.

Topological structures evolution

The chamber group can be regarded as a mixed topological structure consisting of series and parallel systems due to its different internal chamber shapes and sizes, variable layout forms, and complex specifications and structures. In order to explore the topological structure evolution characteristics of the chamber group and obtain the overall instability inertia, it is assumed that the chamber group evolves from individual chamber, and sequentially adds a chamber, which is placed in series or parallel at any position of the original structure, thus forming a new structure. According to the above analysis, the topological structure containing parallel systems has one and only one chamber on each branch, so all the evolution characteristics of the chamber group can be obtained by permutation and combination, as shown in Fig. 3.

It can be seen that, I is individual chamber with one topological structure. Adding a chamber to I will form two-chamber group, including two topological structures, namely series and parallel, corresponding to II and III. Adding another chamber to form three-chamber group will begin to change dramatically. The added chamber can either form a series topological structure IV with II, or a parallel topological structure VI with III, or as a branch connected in parallel to any chamber in II to form a mixed series–parallel topological structure V. In terms of four-chamber group, the combination of the newly added chamber and the original topological structure can be divided into four forms: one is combined with IV to form a series topological structure VII; the other is combined with VI to form a parallel topological structure V; the third is combined as a chamber on the series line with V to form a more complex mixed series–parallel topological structure VIII; the fourth is combined as a branch connected in parallel to V to form a mixed series–parallel topological structure IX. Continuing to add chambers will make the topological structures more and more complex. For a chamber group with n chambers, the number of topological structures is also n, numbered from \(\frac{n(n - 1)}{2}\) to \(\frac{n(n + 1)}{2}\), including one series topological structure, one parallel topological structure, and n−2 mixed series–parallel topological structures, where the number of chambers in series lines are sequentially n−2, n−3, n−4, …, 2, 1; and the corresponding number of parallel chambers are 2, 3, 4, …, n−2, n−1.

Squares were used to represent a topological structure, and solid arrows were used to represent adding a chamber, the topological structures evolution of chamber groups were obtained, as shown in Fig. 4. Due to the complex evolution process of the n-chamber group, the dotted arrows were used to represent the process of adding one chamber at the corresponding position by series, parallel, or mixed connection on the basis of the n−1 chamber group.

According to the topological structures evolution of chamber groups, the chain instability inertias can be quantitatively expressed as shown in Table 1. For individual chamber, the chain instability inertia is always 1. While for two-chamber group, there are two evolution paths, namely series and parallel, with chain instability inertia of 1 and 0 respectively. As the number of chambers increases, the structure of the chamber group becomes more complex, and in addition to simple series and parallel connections, mixed topological structures appear, resulting in corresponding changes in the chain instability inertia of the chamber group. Under the condition of three-chamber group, the chain instability inertias are 1, 0.33, and 0 respectively. As the number of chambers continues to increase, variations in mixed topological structures increase, resulting in a diversified trend in the chain instability inertia. Taking the four-chamber group as an example, the chain instability inertia chain are 1, 0.50, 0.25, and 0 respectively. Similarly, it can be seen that in an n-chamber group, if there are 0, 1, …, m, …, n important chambers, their chain instability inertia are 0, 1/n, …, m/n, …, 1 respectively.

Key chambers identification method

Structural importance analysis

The importance refers to the degree of influence that a change in the state of a unit on the stability of the system. It can be used to identify weak links in the system, locate key areas, and provide a basis for system stability control and support design27. Based on the reliability theory, each failure mode corresponds to a basic event28. Therefore, the importance of each chamber in a group is equal to the sum of the importance of the basic events. In the stability analysis of a chamber group, instability is the only failure mode, and the importance of the chamber is equivalent to that of the basic event. According to the above analysis, the state of each chamber can be divided into two states: stability and instability. Therefore, there are 2n combinations of chamber states within the n-chamber group, which can be attributed to two states: overall stability and chain instability. Each combination of chamber states is referred to as the microstate of the system, and the overall stability or chain instability of the chamber group is referred to as the macro-state of the system. Therefore, a two-state system with n-chambers has 2n microstates, and can be attributed to two macro-states.

The topological structure importance of chamber group is to analyze the impact of each basic event on the occurrence of chain instability based on the system structure. The importance of the system reflects the contribution of micro-states to macro-state changes. There are generally two methods for analyzing structural importance29,30: one is qualitative, which uses minimum cut sets or minimum path sets to rank structural importance. The other is quantitative, which accurately calculates structural importance coefficients. As an effective mathematical tool that can accurately describe the stability relationship of a system, the structural function has been widely used in aerospace, mechanical electronics, and other fields31,32. According to the above analysis, changes in the micro-state of the system will have a direct or indirect impact on the macro-state, that is, the instability state of the chamber is mapped under different topological structure evolution characteristics, which determines the stability state of the chamber group. Therefore, the chamber state can be described by using a binary variable xi:

The state of the chamber group can be represented by the n-dimensional structural function φ(X):

When the state of a chamber xi changes from stability (0) to instability (1), and the states of other chambers remain unchanged, there are three possible patterns for the chamber group:

Pattern A: The state of the chamber group changes from 0 to 1, i.e., the chamber group changes from overall stability to chain instability. Pattern B: The state of the chamber group is 0, i.e., the chamber group is overall stability. Pattern C: The state of the chamber group is 1, i.e., the chamber group is chain instability. Since the stability problem of the chamber group conforms to the characteristics of a typical monotonic relational system (Pattern A), Patterns 2 and 3 are not considered.

According to the above analysis, as a two-state system, the internal chamber state combinations of n-chambers are 2n. For a given state of chamber xi, there are a total of 2n−1 combinations of states for the remaining n−1 chambers. The contribution of chamber xi instability to the chain instability of the chamber group can be expressed as:

It can be seen that Eq. (5) is an accumulation of Pattern A, which indicates the total number of changes in the state of the chamber group due to state changes of chamber xi. Moreover, the state of the chamber group is not only affected by changes in the state of individual chamber, but also determined by the topological structures of the chamber group. As the chambers arranged in series, parallel or mixed, the chain instability inertia of different topological structures will directly affect the chain instability occurrence in the chamber group. Therefore, the structural importance Ti of chamber xi is determined by the product of the chain instability inertia and the total number of chamber group states where chamber xi as important chamber, compared to the number of other n−1 chamber state combinations.

Therefore, the structural importance of the two-chamber, three-chamber, and four chamber groups are analyzed, the corresponding topological structures are II, III, IV…V. For two-chamber group, the states of chambers x1 and x2 can be divided into four combinations, and each combination affects the chamber group under topological structures II and III. The truth values of the two-chamber group states are shown in Table 2. In topological structure II, chambers x1 and x2 are both important chambers, and the chamber group is in a metastable state. When the state of chamber x1 is 1, the corresponding chamber group state number is 2, and when the state is 0, the corresponding chamber group state number is 1. From Eq. (6), it can be seen that the structural importance of chamber x1 under topological structure II is Tx1 = 0.50. Similarly, it can be seen that of chamber x2 is Tx2 = 0.50, i.e., Tx1 = Tx2. However, for topological structure III, chambers x1 and x2 are both general chambers, and the chamber group is in a stable state which will not change due to individual chamber instability. Therefore, the structural importance of chambers under topological structure III is Tx1 = Tx2 = 0. The structural importance of each chamber in the two-chamber group is shown in Table 3.

According to the topological structure evolution characteristics, the number of chambers is positively correlated with the topological structure of the chamber group. The three-chamber group contain three topological structures (IV, V, VI), and the states of chambers x1, x2, and x3 can be divided into eight combinations, as shown in Table 4. In topological structure IV, all three chambers are important chambers, and the chamber group is in a metastable state. Therefore, it can be determined that the importance of each chamber under topological structure IV is Tx1 = Tx2 = Tx3 = 0.25. For topological structure V, it is also in a metastable state but the chain instability inertia is less than IV. When the state of chamber x1 is 1, the corresponding state number of chamber group states is 4, and when the state is 0, the corresponding state number of chamber group states is 1. The importance of chamber x1 is Tx1 = 0.25. Similarly, the importance of general chambers × 2 and × 3 is Tx2 = Tx3 = 0.08. The chamber group in topological structure VI is in a stable state, so the importance of each chamber is Tx1 = Tx2 = Tx3 = 0. The structural importance of each chamber in the three-chamber group is shown in Table 5.

In the four-chamber group, there are four topological structures (VII, VIII, IX, X), and the states of chambers x1, x2, x3, and x4 can be divided into sixteen combinations, as shown in Table 6. From the above analysis, it can be seen that the topological structure VII~IX are all in a metastable state with the chain instability inertia decreases gradually, while the chamber group under topological structures X are all in a stable state. According to the above analysis, the importance of each chamber under the topological structure VII is Tx1 = Tx2 = Tx3 = Tx4 = 0.13. For the topological structure VIII, when the state of chamber x1 is 1, the state corresponding number of chamber group states is 8, and when it is in state 0, the corresponding state number of chamber group is 5. The structural importance of chamber x1 is Tx1 = 0.19. Similarly, the structural importance of important chamber x2 is Tx2 = 0.19, i.e., Tx1 = Tx2. The structural importance of general chamber x3 and x4 is Tx3 = Tx4 = 0.06. For the topological structure IX, when the chamber x1 is in state 1, the corresponding state number of chamber group is 8, and when it is in state 0, the corresponding state number of chamber group is 1. The structural importance of chamber x1 is Tx1 = 0.22. Similarly, the structural importance of general chamber x2, x3, and x4 is Tx2 = Tx3 = Tx4 = 0.03. The chamber group under the topological structure X is in a stable state, and the structural importance of each chamber is Tx1 = Tx2 = Tx3 = Tx4 = 0. The structural importance of each chamber in the four-chamber group is shown in Table 7.

According to the above analysis, it is found that the topological structure not only has a significant impact on the chain instability inertia of the chamber group, but also directly determines the structural importance of each chamber. As shown in Table 8, in the n-chamber group, the chamber state can be divided into 2n combinations, where \(\frac{n(n - 1)}{2}\) is the series, i.e., there are n important chambers, and the chamber group is in a metastable state. At this time, when the state of chambers x1, x2, …, xn is 1, the state of the chamber group is 2n−1, and when the state of chambers x1, x2, …, xn is 0, the state of the chamber group is 2n−1–1. Therefore, the structural importance of all chambers in the chamber group is \(\frac{1}{{2^{n - 1} }}\). When m important chambers appear in the n-chamber group (m < n), there are two situations:

(a) When m = 1, there is only one important chamber x1, the chamber state is 1, and the chamber group state is 2n−1. When the chamber state is 0, the chamber group state is 1. For general chambers, the contribution of chamber xi instability to the chain instability of the chamber group is 1. Therefore, the structural importance of each chamber can be expressed as:

(b) When 2 ≤ m < n, there are two or more important chambers, the state of the chamber group with chamber state 1 is 2n−1, and the state of the chamber group with chamber state 0 is 2n−1-m−1. And, the contribution of general chamber xi instability to the chain instability of the chamber group is still 1. Therefore, the structural importance of each chamber can be expressed as:

For the topological structure \(\frac{n(n + 1)}{2}\), chambers x1, x2, …, xn are parallel, and the chamber group is stable, with a chain instability inertia of 0. Therefore, the structural importance of all chambers is 0. As shown in Table 9, it is found that in the series system, the structural importance of each chamber is the same. In the mixed system, the structural importance of each chamber in the series line is the same, those in the parallel line is also the same, and the series line is greater than parallel line. While in the parallel system, the structural importance of each chamber is 0.

Key chambers identification

The first step to prevent the occurrence of chain instability in the chamber group is to effectively identify and distinguish the key chambers. Among the 2n micro-states, not every change can lead to a variation in the macro-state of the system. Those chambers that cause macro-state change when and only when their state changes are called key chambers. According to the above analysis, the structural importance of important chambers is generally greater than that of general chambers, so it can be determined that there is a relationship between key chambers and important chambers as follows:

According to Eq. (9), when the chain instability inertia is 0, the chamber group is a parallel system composed of general chambers, and there is no key chambers. When the chain instability inertia is 1/n, the chamber group is a mixed system composed of one important chamber and several general chambers. At this time, the important chamber can be considered as the key chamber. When the chain instability inertia is greater than m/n, there are two or more important chambers in the chamber group, the chamber group is a mixed system, and the key chamber exists within m important chambers. At this time, it is necessary to further identify the key chamber considering the self-condition of the chamber and the influence of external disturbance. According to the instability mechanism of the chamber group, it is found that when the static and dynamic superimposed stress exceeds the bearing strength of the anchored surrounding rock and there is residual energy, the plastic rock will loosen and turn to accelerated instability23,24. Therefore, the key chamber identification can be expressed as:

where δσ is the instability stress index, δU is the instability energy index.

where σj is internal static stress, MPa; σd is external dynamic stress, MPa; σmc is anchorage bearing strength, MPa; Uj is internal static energy, kJ; Ud is external dynamic energy, kJ; Umc is energy consumed by anchorage failure, kJ.

Gs is referred to as the key coefficients, which can reflect the key degree of the chamber in the group. It can be seen that in the mixed topological structure, the structural importance of chambers in series lines is greater than that of in parallel lines, and the internal components of each line are equivalent. Therefore, the instability stress and energy indexes become the main factors affecting key chambers identification. According to the instability mechanism, it can be seen that chamber instability must meet both stress and energy criteria, that is δσ > 1 and δU > 1. Therefore, the chamber with the maximum value of Gs among the m important chambers is identified as the key chamber.

As the weak link in the chamber group, the key chamber plays a vital role in its overall stability. It is found that the main factors affecting the key chambers identification include three parts: First, chain instability inertia, which represents the difficulty of chain instability in the chamber group. The greater chain instability inertia, the more instability links will be generated. And it is necessary to simultaneously identify m important chambers as key chambers. Second, the important chambers conditions. According to the instability mechanism, key chambers generally have characteristics such as large cross-sectional, low support strength, and strong interaction effects. Third, external disturbance. Key chambers have higher sensitivity to external loading variation. Even under the same disturbance, key chambers will be the first to instability. The identification process of key chambers is shown in Fig. 5.

In a mixed system, any important chamber can be determined as a key chamber, which means that any important chamber can be found in the 2n micro-states of the chamber group as a key chamber. However, whether it becomes a key chamber depends on the state combination of the other n−1 chambers. Therefore, the identification of key chambers should be carried out under a fixed topological structure. Since the state of each chamber will affect the overall stability of the chamber group, the following principles should be followed during key chambers identification and stability control:

(a) Structural principle. The key chambers identification is closely related to the chamber group structure. Within a fixed area, the chain instability inertia and key chamber locations of a three-chamber group and a four-chamber group may not be the same, and there may be differences in the instability stress and energy indexes.

(b) Diversity principle. The objects of key chamber identification are generally considered to be important chambers on the series line. If the key coefficients of two or more important chambers are the same and the largest, it indicates that there may be multiple key chambers in the group, which forms a"series key chamber group". Similarly, it is generally believed that general chambers on parallel lines will not cause changes of chamber group state. In field engineering applications, however, when multiple chambers occur instability simultaneously, the superimposed of surrounding rock stress and energy will change significantly. That is to say, the general chambers does not mean the state would not affect the chamber group stability, but it requires certain conditions. The key coefficients of several parallel chambers are greater than those of series chambers. At this time, there is a relationship as follows:

where n is the total number of chambers, m is the number of general chambers, and w is the number of stable chambers in parallel chambers. At this point, the maximum value of the key coefficient in important chambers can be used as a threshold to distinguish the simultaneous instability of several general chambers, which leads to the chain instability of chamber group. In other words, the simultaneous instability of n-m-w general chambers is equivalent to the instability of one important chamber. These parallel chambers can be called"parallel key chamber groups". The division of key chamber groups is shown in Fig. 6.

(c) Dynamic principle. This principle includes two aspects: on the one hand, the key chambers identification is based on the specific chamber group and certain stress environment. When any one of these conditions changes, the weak links in the chamber group will also change accordingly, and the key chambers need to be re-determined. On the other hand, taking key chambers as the support focus, the key coefficients and structural importance will change, which means that the topological structure of chamber group will be different. The original key chambers in series lines may be transformed into general chambers in parallel lines. At this time, new weak links will appear in the chamber group, and it is necessary to relocate the key chambers and reevaluate the possibility of chain instability in the chamber group.

(d) Priority principle. In the process of stability control of the chamber group, the priority should be determined based on structural importance and key coefficients. In the chamber group, priority should be given to reinforcing important chamber. The control methods include but are not limited to intensive support, high-strength materials usage, monitoring and early warning strengthening, etc. When there are multiple important chambers, the stability control of surrounding rock should be carried out in the order of key coefficients from high to low.

Conclusion

-

(1)

The topological structure of the chain instability of the chamber group was established, in which the chamber was divided into important chambers and general chambers. The ratio of the number of important chambers to all chamber was defined as the chain instability inertia, which was used to reflect the difficulty of chain instability of the chamber group. The topological structure evolution was inverted, and the concept of structural importance was introduced to quantitatively characterize the influence of the micro-state of each chamber on the macro-state of the chamber group.

-

(2)

The key chambers identification method was proposed. When the chain instability inertia is 0, there are no key chambers; when the chain instability inertia is 1/n, important chambers are key chambers; when the chain instability inertia is greater than m/n, the chamber with the largest key coefficient is the key chamber. In addition, the principles of structural, diversity, dynamic, and priority were proposed for identification.

-

(3)

This paper aims to identify the key chambers that may trigger chain instability and locate the weak links in the chamber group. Not only is it beneficial for source control of chain instability, but it also provides a feasible approach to cut off the chain by clarifying control priority based on the key coefficient. On this basis, targeted and directional support design for key chambers is critical, which established a quantitative and effective framework for the stability control of chamber group.

-

(4)

Conventional methods were simplified by ignoring group interactions and chain effect to systemic stability. This research bridged this gap through reliability theory, offering a tool for targeted, data-driven stability control. It should be noted that the dynamic-evolution and time-dependent factors were not considered. Further optimization to chain instability inertia and structural importance were needed to meet the wider universality and adaptability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yang, S. et al. The stability of roadway groups under rheology coupling mining disturbance. Sustainability-Basel. 13, 12300 (2021).

Liu, X. S. et al. Failure evolution and instability mechanism of surrounding rock for close-distance parallel chambers with super-large section in deep coal mines. Int. J. Geomech. 21, 04021049 (2021).

Xiong, Y. et al. Instability control of roadway surrounding rock in close-distance coal seam groups under repeated mining. Energies 14, 5193 (2021).

Wang, J., Ma, L., Liu, P., Chen, P. C. & Song, L. Z. Study on soft rock chamber groups support technology in deep mine. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 31, 330–340 (2023) ((In Chinese)).

Pan, H. et al. Distribution characteristics of deviatoric stress and control technology of surrounding rock at temporary water chamber group in deep mining. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 2, 55–63 (2020) ((In Chinese)).

Sun, X. M., Zhao, C. W., Tao, Z. G., Kang, H. W. & He, M. C. Failure mechanism and control technology of large deformation for Muzhailing tunnel in stratified rock masses. B. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 4731–4750 (2021).

Liu, X. S. et al. Similar simulation study on the deformation and failure of surrounding rock of a large section chamber group under dynamic loading. Int. J. Min. Sci. Techno. 31, 495–505 (2021).

Fan, D. Y., Liu, X. S., Tan, Y. L., Li, X. B. & Lkhamsuren, P. Instability energy mechanism of super-large section crossing chambers in deep coal mines. Int. J. Min. Sci. Techno. 32, 1075–1086 (2022).

Yuan, W. H., Hong, K., Liu, R., Ji, L. J. & Meng, L. Numerical simulation of coupling support for high-stress fractured soft rock roadway in deep mine. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 7221168 (2022).

Fan, D. Y., Liu, X. S., Tan, Y. L., Li, X. B. & Yang, S. L. Energy mechanism of bolt supporting effect to fissured rock under static and dynamic loads in deep coal mines. Int. J. Min. Sci. Techno. 34, 371–384 (2024).

Kang, H. P., Jiang, P. F., Wu, Y. Z. & Gao, F. Q. A combined “ground support-rock modification-destressing” strategy for 1000-m deep roadways in extreme squeezing ground condition. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 142, 104746 (2021).

Kang, H. P., Lin, J., Yang, J. H., Wu, Y. Z. & Gao, F. Q. Stress distribution and synthetic reinforcing technology for chamber group with soft and fractured surrounding rock. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 33, 808–814 (2011) ((In Chinese)).

Zhu, C., Yuan, Y., Yuan, C. F., Wang, W. M. & Meng, C. G. Stability evaluation and layout of surrounding rock in deep large section tunnel. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 37, 11–22 (2020) ((In Chinese)).

Zhu, C. et al. Research on the “three shells” cooperative support technology of large-section chambers in deep mines. Int. J. Min. Sci. Techno. 31, 665–680 (2021).

He, M. C. & Wang, Q. Excavation compensation method and key technology for surrounding rock control. Eng. Geol. 307, 106784 (2022).

He, M. C., Li, G. F., Ren, A. W. & Yang, J. Analysis of the stability of intersecting chambers in deep soft-rock roadway construction. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 37, 167–170 (2008).

Gao, W. & Zheng, Y. R. Ant colony algorithm and its application into optimization of construction order for underground house groups. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 4, 471–474 (2002) ((In Chinese)).

Huang, Y. B. et al. Failure mechanism and construction process optimization of deep soft rock chamber group. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 50, 69–78 (2021) ((In Chinese)).

Wei, S. Q., Zhang, J. X., Zhang, W. H. & Ma, L. Q. Bolt-grouting combined support technology for large-scale chamber group with high ground pressure. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 03, 281–285 (2008) ((In Chinese)).

Cheng, H., Cai, H. B., Rong, C. X., Yao, Z. S. & Li, M. J. Rock stability analysis and support countermeasure of chamber group connected with deep shaft. J. China Coal Soc. 36, 261–266 (2011) ((In Chinese)).

Wang, J., Wang, H., Guo, Z. B., Hao, Y. X. & Cui, J. S. Stability control strategy of high stress and intense expansion soft rock underground openings for pump house in deep mine. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 32, 78–83 (2015) ((In Chinese)).

Xin, C. Y., Gao, F., Song, L. Y., An, Y. & Li, Y. Y. Two strong stability control technology of pump chamber group under deep and complicated conditions. Coal Sci. Technol. 43, 23–28 (2015) ((In Chinese)).

Tan, Y. L., Wang, H. L., Fan, D. Y., Liu, X. S. & Wang, X. Stability analysis and determination of deep large-section multi-chamber group in coal mine. Geomech. Geophys. Geo. 8, 14 (2022).

Tan, Y. L. et al. Research progress on chain instability control of surrounding rock for super-large section chamber group in deep coal mines. J. China Coal Soc. 47, 180–199 (2022) ((In Chinese)).

Jia, L. M. & Lin, S. Current status and prospect for the methods of system reliability. Syst. Eng. Electron. 37, 2887–2893 (2015) ((In Chinese)).

Yi, H. & Liang, X. F. Theory and practice of pan reliability engineering (Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press, 2017).

Sedaghat, N. & Ardakan, M. A. G-mixed: A new strategy for redundant components in reliability optimization problems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safe. 216, 107924 (2021).

Pourhassan, M. P., Raissi, S. & Hafezalkotob, A. A simulation approach on reliability assessment of complex system subject to stochastic degradation and random shock. Eksploat. Niezawodn. 22, 370–379 (2020).

Kang, R. & Wang, Z. L. Reliability systems engineering: A research review and prospect. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 43, 180–190 (2022) ((In Chinese)).

Jin, Y. X., Geng, J., Lv, C., Chi, Y. & Zhao, T. D. A methodology for equipment condition simulation and maintenance threshold optimization oriented to the influence of multiple events. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safe. 229, 108879 (2023).

Rafiee, K., Feng, Q. M. & Coit, D. W. Reliability modeling for dependent competing failure processes with changing degradation rate. IIE Trans. 46, 483–496 (2014).

Shi, Y., Zhu, W. H., Xiang, Y. S. & Feng, Q. M. Condition-based maintenance optimization for multi-component systems subject to a system reliability requirement. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safe. 202, 107042 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52374218, 52174122), Excellent Youth Fund of Shandong Natural Science Foundation (ZR2022YQ49), Taishan Scholar Project in Shandong Province (No. tsqn202211150).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China, 52404088, 52374218, Excellent Youth Fund of Shandong Natural Science Foundation, ZR2022YQ49, Taishan Scholar Project in Shandong Province, tsqn202211150.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y. contributed to conception, design of the research and formal analysis. X.S. and Y.L. was responsible for establishment and calculation of numerical models. Y.L. and X.B. performed the design of prevention measures. D.Y. and X.S. wrote original draft, writing-review and editing. X.B. and S.L were responsible for data screening and verification. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, D., Liu, X., Tan, Y. et al. Structural importance analysis and key chambers identification for chain instability of chamber group in coal mine. Sci Rep 15, 23219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06216-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06216-1