Abstract

Tennis, as a popular competitive sport, has complex rules and requires high accuracy and fairness in penalization. To improve the accuracy and speed of the penalty, the study proposes a hawk eye detection method for tennis games based on YOLOv5 and TensorRT. First, YOLOv5 is used for target detection to achieve efficient tennis feature extraction. Second, TensorRT is introduced for inference acceleration to improve the real-time performance of the model through layer fusion and memory optimization. The experimental results show that the model achieves 94% mean average precision in the tennis ball detection task, with a combined detection error of 0.39 m and a minimum computing time of 2.28 s. The study shows that this method can significantly improve the accuracy and speed of tennis ball drop detection, which provides reliable technical support for the penalization of tennis matches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tennis is a sport with a long and wide-ranging history, originating in 19th century England, and is now one of the most popular competitive sports worldwide1. The rules of tennis matches are relatively complex, including various technical movements such as serving, receiving, drawing, and intercepting. The outcome of the game is determined by the player’s accumulated scores in multiple games2. Therefore, it has high viewing and competitive value, attracting a large number of viewers and media attention, while also bringing challenges to the rigor and fairness of game judgments. To meet the high-precision judgment requirements of tennis competitions, the detection of ball landing points has increasingly attracted attention. Y. Ke et al. proposed an object detection algorithm for tennis recognition that integrates deep learning techniques and incorporates prior knowledge of the ball’s impact region to effectively address the advanced visual task of ball detection. Experimental results showed that the algorithm could achieve higher detection accuracy and faster detection speed, improving the accuracy and reliability of tennis ball impact detection3. D. Gao et al. proposed an automatic small object detection method based on deep learning to address the low detection accuracy of small objects in tennis videos. The results of the experiment demonstrated that this method exhibited high integrity in the collection of tennis video information and a short detection time4. Y. Zhao et al. raised a lightweight tennis detection algorithm that combines the You Only Look Once version 5 (YOLOv5) algorithm with Robomate EP to address issues such as poor recognition performance, low detection accuracy, and high model parameters and computational complexity in traditional tennis detection algorithms. The experimental results showed that, compared to the original version, the algorithm’s parameters and computational complexity were reduced by 42% and 44%, respectively, while the average detection accuracy increased by 2%5. Z. Rong et al. proposed a table tennis target detection method based on deep learning and multi-scale feature fusion to improve the ball detection accuracy in table tennis matches. The experimental results showed that the new method achieved the highest value of 87.3% average detection accuracy, which was significantly better than other methods and had higher robustness6. Y. Yang et al. developed a tennis trajectory prediction method by combining artificial neural network detection algorithms and stereo vision to promote the accuracy and speed of measuring tennis trajectories and predicting their binding positions. The experiment outcomes denoted that this method had high reliability and robustness7.

With the quick advancement of computer vision technology, deep learning-based object detection methods have demonstrated excellent performance in various visual tasks. Especially the You Only Look Once (YOLO) series models, with their efficient, fast, and accurate object detection capabilities, have become a focus of attention for researchers and engineers8. As the most recent iteration of the series, YOLOv5 represents a significant advancement in terms of both accuracy and speed of detection, while also exhibiting considerable potential for practical applications. F. Lei et al. found that underwater object detection often failed to achieve satisfactory detection results. Therefore, researchers proposed a new detection method after using YOLOv5 and a multi-scale feature fusion path aggregation network. The experiment outcomes denoted that the average accuracy of this method was as high as 87.2%9. Z. Zhao et al. found that current particle board surface defect detection technology has low accuracy. To this end, researchers proposed a novel detection method by combining gamma ray transformation and YOLOv5. The experiment outcomes denoted that this method increased the recall rate and F1 by 3.75% and 5.42% respectively compared to the original method10. J. Zhou et al. established a perception model based on a target vision detection system using YOLOv5 to realize real-time detection of unmanned speedboats near ships ahead. The results of the experiment indicated that the model exhibited a detection accuracy of 98.0% and a recall rate of 96.2% for images of ships11. X. Liu et al. proposed a novel tennis detection model based on YOLOv5 and K-means clustering algorithm to solve the scale diversity, small targets, and complex backgrounds in tennis object detection. The experiment outcomes denoted that the average accuracy of the model was 9% higher than that of YOLOv5 alone12. Y. Hou et al. proposed a novel tennis landing point edge detection algorithm by combining YOLOv5 and a convolutional attention module to further improve the object detection performance in tennis. The experiment findings denoted that the average accuracy of the algorithm in real tennis courts was 87.3%, which was 3.4% higher than before the improvement13. Shi X et al. pointed out that traditional counting methods in aquaculture involve high labor costs, low efficiency, and significant counting errors. Therefore, the team proposed an object detection optimization algorithm based on YOLOv7 network, which was deployed on Jetson Nano edge device through TensorRT acceleration framework to achieve real-time target detection of underwater marine treasures. In terms of performance, the approach maintained high recognition accuracy and achieved fast inference on the Jetson Nano experimental platform14. Yan H et al. proposed the YOLO detection algorithm applied to the edge device to balance the speed and accuracy of the circuit defect detection algorithm. The algorithm used GhostNetV2 to reconstruct the C3 module in the YOLOv5 model and used TensorRT to optimally accelerate the model. Experimental results showed that the method could accurately identify defective samples, and the YOLO detection algorithm had excellent generalization ability under harsh conditions of low-light and snowfall weather conditions15.

In summary, previous studies have made significant progress in tennis target detection using deep learning techniques, improving detection accuracy and speed. It also demonstrates that YOLOv5 has end-to-end detection, efficient feature extraction, and adaptive anchor frame mechanism, which is suitable for tennis ball drop detection task and can maintain high accuracy under complex background to meet real-time detection requirements. However, these methods still have shortcomings in dealing with small objects and complex backgrounds, and the large model parameters and computational complexity have a significant impact on practical application results. To this end, the study introduces GhostNet based on YOLOv5 to reduce computational redundancy and improve detection speed, while BiFPN is used to enhance the multi-scale feature fusion capability, so that the model can more accurately detect small objects moving at high speeds and optimize the detection accuracy of tennis ball drop points. In addition, the real-time inference optimization engine, Tensor Real-Time (TensorRT) technology, is added for layer fusion and memory optimization. The innovations of this study are as follows: (1) Combining GhostNet to improve feature extraction efficiency and using BiFPN to enhance small target detection capability. (2) Using TensorRT for layer fusion and memory optimization to improve real-time performance. (3) Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) algorithm is introduced to reduce parallax error and improve the accuracy of three-dimensional (3D) coordinate estimation of the drop point. The contribution of the research lies in the following two points. Firstly, a novel tennis hawk-eye detection method based on YOLOv5 and TensorRT optimization is proposed, which is specifically designed for real-time detection of fast-moving targets in tennis matches. Secondly, the integration of GhostNet, TensorRT, accelerated inference and RANSAC within the model facilitates enhanced feature extraction, layer fusion, and memory optimization. This, in turn, leads to the optimization and improvement of complex spatial coordinate modelling of tennis balls. Consequently, these optimizations enhance the efficiency and real-time performance of the model, while also ensuring enhanced robustness and accuracy. The research aims to further improve the accuracy of tennis match judgments and provide more effective assistance for the technological development and fairness of the field.

Methods and materials

The traditional Hawk Eye System (HES) has been found to have a relatively low level of accuracy. To address the challenges of tennis object detection under varying lighting conditions, complex backgrounds, and other factors that affect detection accuracy, a more robust solution is needed. The study not only performs real-image projection calculation in the HES, but also combines YOLOv5 object detection to improve the accuracy of tennis trajectory recognition. Moreover, TensorRT is utilized to accelerate inference to ensure real-time performance. In addition, to improve the accuracy of coordinate calculation, RANSAC is introduced to optimize the field calibration, and triangulation is used to correct the multi-camera data to ensure the accuracy of the landing point judgment. Comprehensively, the study combines multi-object detection, computational optimization, and coordinate transformation to improve detection accuracy and real-time performance, and provide reliable judgment support for tennis matches.

HES and field coordinate construction

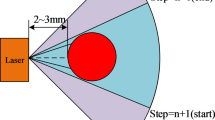

HES, officially known as Instant Playback System, is an advanced technology for assisting in sports match refereeing. It utilizes multiple cameras to capture the trajectory of the ball and uses computer vision and image processing techniques for 3D reconstruction and trajectory analysis to provide accurate refereeing results16. Specifically, the HES can be used to reproduce 3D scenes of controversial ball points and assist in refereeing. The entire system includes system architecture construction, detection scene planning, hardware parameter adjustment, 3D scene modeling, object detection algorithm design, etc. The hardware and software architecture of HES is shown in Fig. 117.

Figure 1 (a) and (b) show the hardware and the software composition distribution of HES. In Fig. 1, the hardware of HES can be divided into venue modules, dynamic video capture, data communication, data processing, and interface interaction. The software part mainly includes several key steps such as image acquisition, image processing, 3D reconstruction, and trajectory analysis. Firstly, multiple high-speed cameras simultaneously capture the motion trajectory of the tennis ball, generating massive image data. Next, the position features of the ball are extracted through image processing algorithms, and these features are reconstructed in three dimensions to form the precise trajectory of the tennis ball. Then, the system uses trajectory analysis algorithms to determine the landing point of the ball and makes judgments based on pre-set rules. Among these modules, the calculation of tennis court coordinates is particularly crucial, as it directly affects whether the system can accurately determine the landing position of the tennis ball18. The calculation of tennis court coordinates involves extracting the motion information of tennis balls from two-dimensional (2D) images captured by multiple cameras, and converting these 2D coordinates into precise positions in 3D space19. This process is usually achieved through stereo matching algorithms and geometric transformations. Firstly, the cameras need to be accurately calibrated to determine the shooting angle and position of each camera. Then, the system synchronously analyzes the images of multiple cameras and uses triangulation to calculate the position coordinates of the tennis ball in 3D space. These coordinates are then compared with the pre-set boundary data of the court to determine whether the tennis ball is out of bounds, ensuring the accuracy and fairness of the penalty. The process starts with a transformation of the 2D image coordinates to the camera coordinate system based on the camera projection model, which can be computed from the perspective projection equation as shown in Eq. (1).

In Eq. (1), P represents the homogeneous coordinates of points on the image plane; K represents the camera’s internal parameter matrix; R means the rotational relationship between the camera coordinate system and the world coordinate system; t means the translation vector; X represents the homogeneous coordinates of points in the world coordinate system. Next, the 3D spatial position of the target point is calculated by triangulation based on the geometric transformation of multiple cameras. At this time, the points under the camera coordinate system can be obtained by inverse transformation, and the calculation method is shown in Eq. (2).

In Eq. (2), \(X'\) represents the coordinates of a point in the 3D space to be solved; A represents the coefficient matrix; b represents a known constant vector. Equation (2) is used to estimate the 3D coordinates of the target point in the camera coordinate system based on the camera’s geometric model and the multi-camera triangulation method. This coordinate is a preliminary estimation result and remains in the camera’s own reference system. Next, Eq. (3) represents the coordinate transformation from the camera coordinate system to the world coordinate system, i.e., the initial coordinates are mapped to points in the world coordinate system by means of an external reference matrix. This transformation is accomplished by pre-calibration, which can effectively correct the deviation of the landing point localization caused by camera placement, rotation, and internal and external parameter errors, etc., and ensure the consistency with the real calibration boundary of the tennis court. It is shown in Eq. (3).

In Eq. (3), \({X_{world}}\) represents the coordinates of a point in the world coordinate system; \({T_{camera}}\) means the transformation matrix from the camera coordinate system to the world coordinate system; \({X_{camera}}\) represents the coordinates of a point in the camera coordinate system. At this point, although the HES can accurately calculate the precise position of the tennis ball in 3D space from the 2D images captured by multiple cameras, due to the presence of parallax information, the farther the tennis ball landing point is from the calibration plate, the greater the judgment error20. Consequently, the study introduces the RANSAC algorithm for matrix transformation optimization. RANSAC is an algorithm that estimates a model by randomly selecting a subset from the data, and is particularly suitable for working with data that contains a large number of outliers. In each iteration, RANSAC selects a small set of data points to fit the model, evaluates the number of interior points in the model, and ultimately selects the model with the most interior points. Its advantage is that it is robust and can effectively tolerate external points. RANSAC can be used to extract real motion trajectories from tennis match data when constructing tennis space models. For example, by estimating the trajectory model of the player or the ball, data points that conform to the motion law can be screened out, and outliers can be ignored to obtain an accurate motion model21,22. The tennis court projection algorithm is based on the real calibration of multiple cameras, and the internal and external parameters of the cameras are optimized by using Zhang Zhengyou calibration method. The field mapping is performed by calculating the uni-responsiveness matrix and combined with the triangulation method for tennis ball drop recovery. The schematic diagram of the calibration points on the site at this time is shown in Fig. 2.

In Fig. 2, some points are randomly selected from the set of calibration points for calculation, including calibration board points such as A, B, C and fixed site points such as D, E, F, G, H, I. These points are evenly distributed. RANSAC calculation is performed through re-projection and transformation optimization, as shown in Eq. (4).

In Eq. (4), \({m_i}\) and \({M_i}\) represent the homogeneous coordinates of the i-th image point and the world coordinate point, respectively; R represents the rotation matrix; E represents the total re-projection error; \(\pi ( \cdot )\) represents the function of projecting camera parameters and world coordinate system points onto the image plane; N means the total number of features; \({\sum _{i \in inliers}}\) means the summation of inlier data. Inlier data refer to those point data that fit the model within the error threshold, i.e., those points where the data have small errors and do not deviate much from the fitted model. The coordinates of the 3D tennis court constructed at this time are shown in Eq. (5).

Tennis silhouette detection based on improved YOLOv5

Most existing tennis detection algorithms are based on traditional object detection algorithms, which are easily affected by factors such as environment, lighting, and court, resulting in detection errors and loopholes. At the same time, HES cannot determine whether a target object of the same volume is a tennis ball after detecting it23,24,25. To this end, the study introduces YOLOv5. YOLOv5 achieves a good balance among detection accuracy, inference speed, and computational resource requirements compared to the subsequent versions, such as YOLOv7, YOLOv8, and YOLOv11. Its model is lightweight and suitable for embedded or low-computing-power devices, while possessing strong small-target detection capabilities. In addition, YOLOv5 has a mature ecology and a stable code framework, which facilitates optimization in combination with GhostNet and TensorRT to ensure real-time and high-precision tennis ball drop detection. The YOLOv5 structure is comprised of four primary components: an input end, a backbone network, a neck network, and a detection end. The input end slices and combines the input image through the Focus layer, then goes through a series of convolutions and Cross Stage Partial 3 (C3) modules, and finally extracts features through the Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP) layer26,27. The backbone network passes these features to the neck network, which combines feature maps of different scales through C3 modules and upsampling operations. Finally, the fused features are passed to the detection end through convolutional and connection layers. The detection end includes multiple convolutions and C3 modules, and ultimately outputs the detection results. The entire regression process can be seen as a fine-tuning process of translation and scaling, and the predicted values of the target area are shown in Eq. (3).

In Eq. (6), \(\sigma\) represents the sigmoid function; \({t_x}\), \({t_w}\), and \({t_h}\) respectively represent the predicted values obtained by the network propagating in various directions; \({b_x}\), \({b_x}\), \({b_w}\), and \({b_h}\) represent the coordinates and width/height of the target area in each direction, respectively; \({p_w}\) and \({p_h}\) respectively represent the width and height of the anchor frame; \({c_x}\) and \({c_y}\) represent the center x and y coordinates of the anchor box, respectively. In the detection box, YOLOv5 adopts the Generalized Intersection over Union (GIoU) method to solve the problem of distance measurement caused by non intersection between the detection area and the target area28. GIoU not only considers the intersection and concatenation of the prediction frame and the real frame, but also introduces the concept of minimum enclosing frame, which provides a more comprehensive measure of the degree of spatial overlap between the target frame and the prediction frame. The calculation method for GIoU and its loss function at this time is shown in Eq. (7).

In Eq. (7), A and B respectively denote the detection area and the target area; C represents the maximum bounding matrix between the detection box and the prediction box. To further improve the detection accuracy and speed of YOLOv5, GhostNet is introduced in the study. In the tennis ball tracking task, the standard convolutional neural network often produces a lot of redundant information when dealing with small spherical features, especially in the case of fast movement and occlusion, which leads to large computation and slow reasoning speed. By introducing the Ghostbottleneck module, GhostNet can generate sparse basic features, and then generate additional ghost features through simple linear transformation, which effectively reduces redundant computation, significantly increases tracking speed, and reduces latency caused by excessive complexity. Compared with traditional methods, GhostNet can maintain high detection accuracy in tennis tracking tasks, while significantly improving real-time performance and adapting to rapidly changing sports scenes. The Ghostbottleneck calculation method is shown in Eq. (8).

In Eq. (8), \(x'\) and \(y'\) respectively denote the input feature map and the output feature map; \({W_{1}}\) and \({W_{2}}\) respectively represent the first layer convolution and the second layer convolution; \(\varsigma\) represents the Ghost feature generation function. The function applies a sparse convolution operation on the input feature maps and generates similar feature maps by linear transformation, thus extending the feature representation capability without increasing the model complexity. At this point, the calculation for the Ghostbottleneck module in the backbone network and the Ghostbottleneck module in the neck network is shown in Eq. (9).

In Eq. (9), \({y_{focus}}\), \({y_{backbone}}\), and \({y_{neck}}\) represent the output feature maps of the Focus layer, backbone network layer, and neck network layer, respectively; \({W_3}\) and \({W_4}\) represent the convolution kernels of the third and fourth layers, respectively. At this point, the feature fusion upsampling and detection output calculation method after combining the Ghostbottleneck module is shown in Eq. (10).

In Eq. (10), \({y_{fusion}}\) and \({y_{\det ection}}\) represent the fused feature map and the feature map of the detection output layer, respectively; \(Concat\) indicates the concatenation operation of feature maps; \(Upsample\) represents the upsampling operation. From the above, it can be seen that \(Upsample\) has optimized the original convolutional layers by lightweighting various modules of YOLOv5, which significantly reduces the computational complexity of the network while maintaining high detection accuracy. At this point, the improved structure of YOLOv5 is denoted in Fig. 3.

In Fig. 3, the blue 1 × 1 border in the figure indicates the target region, i.e., the actual location region of the tennis ball. The green dots are the anchor points used by the YOLOv5 algorithm to localize the target, which indicates the network’s initial estimation of the target’s possible location. The red dashed box indicates the pre-detection region, which is gradually adjusted and optimized through the regression process of the YOLOv5 network to finally determine the target location. Specifically, the input side of the model slices and combines the input tennis images through the Focus layer to effectively extract the key information of the images. Then, multi-layer feature extraction is performed through the CAG-Backbone backbone network consisting of Ghostbottleneck and Cross Aggregated Ghost Convolution 3 (CAGC3) modules to enhance the model’s ability to capture detailed features. These extracted features are then passed to the Bi-directional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN), which fuses feature maps at different scales through the C3 module, convolution, up-sampling, and BiFPN-Contact layers to enhance the recognition of small targets (e.g., tennis balls). Ultimately, these fused feature maps output target detection results through the detection head.

Tennis Hawk eye detection with tensorrt acceleration

After constructing the improved YOLOv5 tennis contour detection model, it was found that because the output data of each layer of the YOLOv5s network is determined by the previous layer, and the parameters of each layer are also affected, there is diversity and complexity in the data distribution. To address this issue, popular new normalization methods such as Batch Normalization (BN) and Instance Normalization (IN) were introduced. Specifically, BN standardizes the inputs of each layer so that the input data of each layer has the same mean and variance when passed to the next layer. This normalization mitigates the so-called “internal covariate bias” problem, where the distribution of inputs in each layer changes as the training process progresses, resulting in slower convergence or unstable training. BN helps stabilize the network during training and accelerates its convergence. For the YOLOv5s network, the introduction of IN helps the network to optimize the features of each input sample independently when dealing with complex backgrounds and small targets (e.g., tennis balls), which improves the model’s adaptability on specific images. Compared to BN, IN is more stable when processing small batches of data and unevenly distributed images, reducing the negative impact due to differences in batch size and data distribution. To enhance the efficiency of target image acquisition and the generalization ability of the detection model in practical application scenarios, TensorRT is employed to optimize the inference performance of the YOLOv5 network, which has been improved based on environmental and lighting factors. TensorRT is a high-performance deep learning inference optimization tool launched by NVIDIA, aimed at improving the inference speed and efficiency of neural network models through various technical means29,30. It mainly includes functions such as layer fusion, precision calibration, and memory optimization. The hardware GPU model that defines the TensorRT pairing is NVIDIA RTX 3060, configured with FP16 precision acceleration of the GPU selected and Tensor Core hardware acceleration enabled. In addition, TensorRT memory management is performed by adjusting the GPU memory pool size31. Taking the Convolution-Batch Normalization-ReLU (CBR) module in YOLOv5 as an example, the new CBR structure fused by TensorRT is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4 (a) and (b) show the CBR structure before and after fusion. From Fig. 4, the CBR structure before fusion contains multiple layer by layer stacked combinations of 1 × 1 and 3 × 3 convolutions, BN, and Leaky ReLU activation functions. This structure has a certain degree of redundant computation in practical inference. After introducing TensorRT, the calculation process is optimized by fusing the convolutional layer and activation function layer. The fused CBR structure combines multiple convolution and nonlinear transformation steps into one operation unit, significantly reducing computation and memory usage, and improving the inference speed and efficiency of the model. The calculation method for CBR module fusion is shown in Eq. (11).

In Eq. (11), Y and \(Y'\) represent the output of the convolutional layer and the output image processed by the ReLU function, respectively; \({b_{conv}}\) represents the bias of the convolutional layer. At this point, the optimized YOLOv5 memory calculation is shown in Eq. (12).

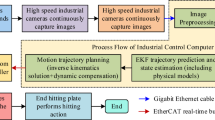

In Eq. (12), \(Laye{r_i}\) represents the i-th layer network; \(Memor{y_i}\) represents the memory requirement of the V-th layer; O indicates the amount of layers in the network. In summary, after combining the improved YOLOv5 and TensorRT, a novel tennis match HED model is proposed. The process of this model is shown in Fig. 5.

In Fig. 5, the process of the new HED model for tennis matches is divided into seven stages. First, the input tennis images are sliced and combined through the Focus layer to generate a feature map. Then, the feature map is passed to the CAG-Backbone network to enhance the feature representation capability through multi-layer feature extraction. Next, the feature map is passed to BiFPN-Neck, which fuses features of different scales through C3 module, convolutional layer, upsampling operation, and BiFPN-Contact layer to further enhance the feature representation capability. Next, the fused feature maps enter the detection head, which is processed by the convolution and C3 modules to output the target detection results. To optimize the detection process, TensorRT is introduced to accelerate the inference and improve the speed and efficiency. Subsequently, RANSAC is used to calibrate and coordinate convert the 2D image to eliminate noise and improve the calculation accuracy of tennis ball position in 3D space. Finally, the GIoU method is combined to compare the detected area with the target area to ensure high accuracy and robustness, and generate accurate penalty results.

Results

To validate the efficacy of the new tennis match HED model, a suitable experimental environment was first established. Experimental parameters were set to validate the efficacy of the raised model, with ablation testing, similar algorithm testing, and tennis ball detection accuracy and error as indicators. Secondly, comparative tests were conducted with real tennis match results to verify the accuracy of the raised model in detecting tennis landing points and trajectories in actual scenarios.

Performance testing of Hawk eye detection model in tennis matches

A suitable experimental environment was established and an optimizer was trained using SGD as the image data. The optimizer factor was set to 0.9 and the initial learning rate was 0.01. The main datasets used in the study were the Grand Slam Tennis Dataset (GSTD) and the UCF Sports Action Dataset (UCF-SAD). The GSTD consists of about 10,000 images and video frames covering a wide range of tennis ball drop samples in different backgrounds, lighting and viewpoints, with a balanced distribution of images in each category. The UCF-SAD dataset contains about 6,000 images covering a wide range of sports, with about 15% (~ 900 images) in the tennis category. To ensure the generalization ability of the models, the GSTD and UCF-SAD datasets were divided according to the ratio of 80% training set and 20% test set, respectively. Specifically, the GSTD training set contains 8,000 images and the test set contains 2,000 images; the UCF-SAD training set contains 4,800 images and the test set contains 1,200 images. In data pre-processing, the study uniformly adjusted all images to 640 × 480 resolution to maintain data consistency. For the problem of category imbalance in the dataset, especially the relatively small proportion of tennis category images in UCF-SAD, the study used data enhancement methods to expand the tennis category samples, including random cropping, flipping and brightness adjustment operations. In addition, all samples were processed in the same way to ensure the fairness and reproducibility of the experiment. In addition, to visualize the data distribution, examples of sample maps for different categories are given in Fig. 6.

Data set illustration display ((a) Source from: https://colorhub.me/photos/nlXVz. (b) Source from: https://colorhub.me/photos/r4ejK).

Other relevant parameters and configurations are denoted in Table 1.

After setting the corresponding HES parameter values, the study first conducted ablation testing using mean Average Precision (mAP) as the indicator. The test results are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 (a) and (b) show the outcomes of the ablation test of the new model on the GSTD and UCF-SAD, respectively. In Fig. 7, with the increase of the amount of test samples, there was a significant improvement in the mAP values of each module. The highest mAP value of the YOLOv5 module alone was only 78%. But after incorporating GhostNet to optimize its convolution and feature extraction, the mAP increased by about 10%. After adding TensorRT again for computation acceleration, the mAP value of the model significantly increased, reaching a maximum of nearly 92%. Finally, coordinate modeling was performed using RANSAC, and the highest mAP value for tennis ball detection was 94%, with a minimum of 240 iterations. In the isolated ablation test, the contribution of GhostNet to small object feature extraction was the most crucial, which significantly improved the model’s boundary determination ability in complex backgrounds. Meanwhile, the introduction of BiFPN strengthened the fusion and transfer of multi-scale information, which made the model’s performance more stable in response to changes in target scales. Compared with the traditional unidirectional feature fusion structure, the bidirectional flow mechanism of BiFPN could realize efficient complementarity between different feature layers, which further improved the robustness of small sphere object detection. The study introduced advanced algorithms of the same type as YOLOv5 for comparison, such as YOLOX, YOLOv5-Lite, YOLOv7, and YOLOv8. The test findings are denoted in Fig. 8.

Figure 8 (a) and (b) show the comparison of detection errors between different algorithms on the GSTD and UCF-SAD, respectively. From Fig. 8, the comparison showed that the YOLOX algorithm exhibited the largest error in the two types of datasets tested, while the algorithm proposed by the study had the smallest performance in terms of error, which was a clear advantage. The quantitative data showed that the detection error of each algorithm increased during the process of increasing the detection distance from 8 to 32 m, but the growth of the error rate of the proposed algorithm was relatively small. Specifically, the algorithm had the lowest combined detection error of 0.39 m in the GSTD dataset and 0.5 m in the UCF-SAD dataset. To combine these error values with actual tennis match scenarios, the study referred to specific standards for tennis court surfaces. The singles court of a tennis court was 23.77 m long and 8.23 m wide, while the line width of a court was usually 0.05 m and the diameter of a tennis ball was about 0.067 m. Therefore, an error of 0.39 m corresponded to an error of approximately 6 tennis ball diameters on the court, while an error of 0.5 m corresponded to an error of approximately 7.5 tennis ball diameters. According to the technical parameters of HESs commonly used in international tournaments such as ATP (Men’s Professional Tennis Association) and WTA (Women’s Professional Tennis Association), the tolerance range of the error of penalty accuracy is usually set between 3.6 mm and 5 mm, but this value is a single-point pixel-level error for the determination of the image boundary, not a 3D spatial trajectory reconstruction error. Therefore, this means that an error of 0.39 m is very small for the HES in professional tennis matches, and is sufficient to meet the accuracy requirements of the vast majority of penalties, especially when the landing point is close to the court line. The study conducted tests using precision (P), recall (R), F1 score (F1), computation time, and model size as indicators, and the test results are denoted in Table 2.

According to Table 2, from the statistical test results, the research model outperformed the other compared algorithms in terms of precision rate (P) in normal, bright and low light environments, and most of the p-values were significantly lower than 0.05, which indicated that its detection performance enhancement was statistically significant, with stronger light adaptation ability and robustness. Compared with other algorithms, especially YOLOX and YOLOv5-Lite, the proposed algorithm of the study not only outperformed other algorithms in terms of accuracy, recall, and F1 value, but also greatly reduced the computing time under different lighting conditions. Specifically, under normal lighting conditions, the research model achieved a P-value of 95.84%, an R-value of 93.57%, and an F1-value of 94.71%, and the computation time was only 2.28 s, which significantly improved the detection speed compared to YOLOv8 (computation time 4.21 s) and YOLOv7 (computation time 5.76 s). However, although the research model performs well in both accuracy and speed, its latency in real-world application scenarios needs to be further explored. For example, the frame rate in tennis matches is usually required to be 60 fps or higher, while the current detection time is 2.28 s, implying that about one frame of image needs to be processed for each detection result. To ensure real-time performance, the detection latency needs to be controlled at the millisecond level to meet the 60fps penalty requirement. In addition, the current experimental deployment is based on RTX 3060 high-performance GPUs, and the scalability of hardware resources needs to be considered to realize the deployment in a professional competition environment. Although the model size is only 7.15 MB, which is suitable for porting to some edge devices, realizing full-scene multi-camera concurrent detection in large-scale competitions still puts high demands on GPU parallel processing capability, memory management and data throughput bandwidth. Therefore, it is necessary to optimize the inference path by combining FPGAs, Jetson Xavier and other high-performance embedded platforms, or to further compress the system latency through distributed computing architecture, so as to meet the real-time demand of high-intensity competition scenarios in the future. In addition, due to the relatively small size of the dataset, to ensure the generalization of the model, the study further used 5-fold cross-validation to evaluate the model performance. Each time, the dataset was divided into five subsets, four of which were used for training and one for testing, and repeated five times to obtain the average performance of the model on different data divisions, and the results are shown in Table 3.

From Table 3, the model performed more consistently in all rounds through 5-fold cross-validation, indicating good stability. The fluctuations in P, R, and mAP were small, showing good generalization. The average F1 for cross-validation was 93.62% and the mAP was 92.39%. Compared with the single division test, the cross-validation method improved the reliability of the model evaluation, which verified that the method can effectively reduce the bias due to the difference in data distribution under smaller datasets.

Simulation testing of Hawk eye detection model in tennis matches

To validate the practical application effect of the HED model proposed by the research in tennis matches, a real tennis court was studied as the test scenario. The venue was 36.57 m long and 18.29 m wide, with a singles boundary length of 36.57 m and a width of 14.23 m. The doubles boundary was 36.57 m long and 18.29 m wide. Assuming that both athletes participate in 9 random matches without causing missed balls, serving without crossing the net, serving out of bounds, or the ball hitting a permanent fixture, the results of the matches are shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9 (a) and (b) showcase the results of the athlete’s 9-round singles match and doubles match, respectively. From Fig. 9, the blue area in Fig. 9 (a) is the effective area for ball drop, and the white area is the ineffective area. After nearly 9 rounds of matches, it was found that the tennis landing points in the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, and 9th rounds were located in the invalid area. In doubles matches, the tennis balls in the 3rd, 7th, and 9th rounds landed in the invalid area. Based on the above competition results, advanced HED algorithm models such as Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN), Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD), and Density Detector (RetinaNet) were introduced for testing. The test outcomes are denoted in Fig. 10.

Figure 10 (a)–(d) showcase the error results of tennis trajectory testing under Faster R-CNN, SSD, RetinaNet, and the proposed model, respectively. In Fig. 10, after conducting cyclic testing on the results of the above 9 rounds of matches, it was found that the detection performance of the HES controlled by Faster R-CNN and SSD was relatively average, with a significant difference from the normal detection values. The maximum was close to 20%. Although RetinaNet’s tennis trajectory and landing trajectory testing was more accurate than the previous two methods, its detection stability was poor and the error rate fluctuated greatly. The method proposed by the research best fitted the real network trajectory detection values, with a minimum trajectory tracking rate error of 5%. The reason for this is that the proposed model is optimized for feature extraction efficiency by GhostNet and combined with TensorRT for inference acceleration, which effectively reduces the detection error. In addition, compared with RetinaNet, the trajectory tracking error of this paper’s method fluctuated less in different rounds, indicating that it has higher stability and robustness in complex background and fast moving target detection. The study continued testing with detection time as the variable, detection angle, and detection distance as reference indicators. The test outcomes are indicated in Fig. 11. The detection angle test refers to the accuracy of the system’s estimation of the angle between the actual direction of motion and the predicted direction of the target during its motion, reflecting the model’s ability to judge the motion trend. While the detection distance test measures the accuracy of the system’s restoration of the true spatial distance of the target when there are different occlusion interferences, i.e., the difference in spatial distances between the detected target drop point and the actual drop point.

Detection angle and distance test for different models (A, B, C and D indicate the moment when the different detection models reach the detection angle stabilization threshold at the 10th, 12th, 13th and 14th seconds, i.e., the time nodes required for the models to complete the establishment of the stable detection capability, respectively); points E, F, G and H denote the point at which the detection distance of each model reaches the minimum error point under the scenarios where the number of occluders is 3, 4, 2, and 1, respectively)

Figure 11 (a) showcases the detection angle test findings of different models, and Fig. 11 (b) showcases the detection distance test findings of different models. “Obstacles” refers to dynamic or static elements that may block the camera’s field of view in the actual game scene, such as the player body, the net, the referee, the pickup players, and the sideline advertisement boards, etc. In Fig. 11, except for the Faster R-CNN model, the detection angles of the other three models fluctuated within a range of 1 °, indicating that the angle deviation of eagle eye tennis ball detection under these methods would be smaller. Among them, the detection time of the model proposed by the research was as short as 10 s. Figure 11(b) compares the detection distance errors of each model under the occlusion of different numbers of obstacles (e.g., players, nets, referees, etc.). From the figure, as the number of obstacles increased from 1 to 5, the detection errors of all models generally rose, but the proposed model of the study still maintained high stability, and its detection distance was always stable at about 9.8 m, and the error was controlled within 0.2 m from the set Hawk-Eye detection benchmark (10 m). Especially at key points such as F, G, and H, the fluctuation of this model was the smallest, indicating that it can still maintain good detection accuracy and robustness under complex occlusion environments, compared with the significant fluctuation of the errors of Faster R-CNN and SSD. The study conducted tests using the metrics of Multiple Object Tracking Precision (MOTP), IDF1 after the mean harmonic of precision and recall, and Multiple Object Tracking Accuracy (MOTA) as indicators. Meanwhile, to ensure the fairness of the comparison, the study used the same benchmark dataset GSTD to implement the other detection methods listed in Table 4. Detection Transformer (DETR), Pyramid Vision Transformer (PVT), and Switched Window Transformer (Swin-Transformer) were introduced. All methods were evaluated on the same dataset and under the same training and testing conditions to ensure comparable results. The test outcomes are denoted in Table 4.

According to Table 4, in the singles and doubles tests, Faster R-CNN performed mediocrely in all metrics, with the highest values of 87.93%, 89.41% and 89.64% for MOTP, IDF1, and MOTA, respectively. In contrast, SSD and RetinaNet improved in detection accuracy and target tracking ability, but their MOTP and IDF1 were still lower than those of the proposed methods, especially in the complex trajectory tracking task with some errors. In addition, the transformation-based detection methods such as DETR, PVT, and Swin-Transformer made progress in improving detection accuracy and stability, and their MOTP, IDF1, and MOTA metrics were better than Faster R-CNN, and some of the metrics were close to or slightly lower than those of SSD and RetinaNet, which show some competitiveness. However, compared with the proposed model, these methods still had gaps in comprehensive detection performance, real-time performance and trajectory tracking accuracy, especially in the doubles test with larger errors. The study-proposed model showed superior results in tennis position and trajectory detection as well as F1 tests in both singles and doubles, with the highest values of 93.68%, 92.51%, and 92.83% for MOTP, IDF1, and MOTA, respectively. Although the tennis ball detection model proposed in the study has improved in terms of accuracy and inference speed, there are some fluctuations in the detection performance when facing different lighting conditions and complex backgrounds. Specifically, under strong light irradiation, the light reflected from the tennis ball surface may lead to the offset of the detection frame, especially in the case of direct light, the edge features of the ball are no longer clear, which in turn affects the localization accuracy of the model. On the contrary, in low-light conditions, the details of the tennis ball are blurred, especially in the contour and edge parts of the ball, which reduces the signal-to-noise ratio of the target detection and leads to a decrease in accuracy. The interference of complex backgrounds is even more significant, especially when the tennis ball is similar to other objects or backgrounds on the field, the model may be affected by the background noise and misidentify other objects as tennis balls, thus increasing the false detection rate. Similar phenomena have been found in other studies. For example, Li et al. pointed out that the detection accuracy of the YOLO series model is often affected in scenes with complex backgrounds, especially in high-contrast scenes where the boundary between background noise and the target is not clear, leading to an increase in the detection error32. In addition, Haruna et al. also found that the robustness of traditional object detection methods is poor under strong light irradiation and low-light conditions, which is especially prominent in high-dynamic range scenes33.

To minimize the influence of these problems in the technical design stage, BN and case normalization were used in the model training to alleviate the interference caused by the lighting change. These methods enhanced the robustness of the model in different lighting environments by standardizing the feature distribution. At the same time, to improve the adaptability of the model to noise and abnormal data, the RANSAC algorithm was introduced to conduct coordinate modeling, so as to effectively deal with some complex background interference. However, although the above measures have improved the performance of the model to some extent, the interference problem of complex background is still not completely solved. In the process of research, it is found that the feature extraction module has insufficient adaptability to the background, and the performance of the model still fluctuates in the scene with large changes in illumination. To this end, future research will further optimize the feature extraction module, explore more feature fusion techniques, and simulate various lighting conditions through data enhancement methods to further improve the generalization ability of the model.

Conclusion

In response to the issue of insufficient detection precision of traditional HES in tennis matches, this study aimed to further raise the detection accuracy and real-time performance of ball landing points and trajectories in tennis matches. Based on the YOLOv5 algorithm as the model framework, GhostNet was introduced to improve feature extraction efficiency, and TensorRT was used for inference acceleration. Finally, a new tennis match HED model was proposed. The experimental results showed that the new model achieved the highest mean detection precision (mAP) of 94% in the tennis detection task, which corresponded to a minimum number of 240 iterations, and improved its detection accuracy by 16% compared to the YOLOv5 algorithm alone. In terms of the integrated detection error, the lowest was 0.39 m in the GSTD dataset and 0.5 m in the UCF-SAD dataset, which was 0.47 m and 0.35 m lower than that of the YOLOX algorithm, respectively. In the MCA, this model had the highest P value of 95.84%, the highest R value of 93.67%, and the highest F1 of 94.71%. In addition, the shortest model detection operation time was 2.28 s, and the smallest model size was 7.15 MB, which has good real-time performance and deployment feasibility. After the simulation test, the proposed model had a minimum error of 5% (%) in network trajectory tracking rate, a maximum difference of 1 degree (°) in detection angle, and a maximum difference of 0.1 m (m) in detection distance in a 9-round real game. Its maximum Multi-Object Tracking Precision (MOTP), IDF1 and Multi-Object Tracking Accuracy (MOTA) values reached 93.68%, 92.51% and 92.83%, respectively. In summary, the improved YOLOv5 model can significantly improve the precision and speed of HED in tennis matches, providing more reliable technical support. However, there are still some shortcomings in this study, such as the need to further improve the detection performance under different lighting conditions and complex backgrounds. Future research will continue to optimize the robustness of the model and explore its potential applications in other sports events.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, Z., Zhao, Y. & Bian, C. The analysis of tennis recognition model for human health based on computer vision and particle swarm optimization algorithm. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 13 (3), 1228–1241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-022-01673-7 (May. 2022).

Shen, C. & Sun, Z. Research on target localization recognition of automatic mobile ball-picking robot. Int. J. Opt. 51 (4), 866–873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12596-021-00805-9 (Jan. 2022).

Ke, Y., Liu, Z. & Liu, S. Apr., Prediction algorithm and simulation of tennis impact area based on semantic analysis of prior knowledge,soft comput., 26, 20, pp. 10863–10870, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-022-07083-y

Gao, D., Zhang, Y. & Qiu, H. Automatic detection method of small target in tennis game video based on deep learning. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 45 (6), 9199–9209. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-231167 (Dec. 2023).

Zhao, Y., Lu, L., Yang, W., Li, Q. & Zhang, X. Lightweight tennis ball detection algorithm based on robomaster. EP Appl. Sci. 13 (6), 3461–3462. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13063461 (2023).

Rong, Z. Optimization of table tennis target detection algorithm guided by multi-scale feature fusion of deep learning. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 1401–1413. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51865-3 (Jan. 2024).

Yang, Y., Kim, D. & Choi, D. Ball tracking and trajectory prediction system for tennis robots. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 10 (3), 1176–1184. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcde/qwad054 (Jun. 2023).

Bian, J. et al. P2ANet: A large-scale benchmark for dense action detection from table tennis match broadcasting videos,acm trans. Multimedia Comput. Commun. Appl. 20 (4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3633516 (Jan. 2024).

Lei, F., Tang, F. & Li, S. Underwater target detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv5,J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10 (3), 310–311. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse10030310 (Jan. 2022).

Zhao, Z. et al. Nov., Real-time detection of particleboard surface defects based on improved YOLOV5 target detection,sci. Rep., 11, 1, pp. 21777–21778, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01084-x

Zhou, J., Jiang, P., Zou, A., Chen, X. & Hu, W. Ship target detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv5,J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9 (8), 908–909. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9080908 (Aug. 2021).

Liu, X., Gong, W., Shang, L., Li, X. & Gong, Z. Aug., Remote sensing image target detection and recognition based on yolov5,Remote Sens., 15, 18, pp. 4459–4460, (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15184459

Hou, Y. et al. R-YOLO: A YOLO-based method for arbitrary-oriented target detection in high-resolution remote sensing images,Sens., vol. 22, no. 15, pp. 5716–5718, Jul. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/s22155716

Shi, X. et al. Sea treasure target detection based on improved Yolov7 and TensorRT deployments, IET Conf. Proc. CP842, The Institution of Engineering and Technology, Stevenage, UK, 2023, vol. 2023, no. 12, pp. 69–73, Sep. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1049/icp.2023.1873

Yan, H., He, Y., Cai, C. & Zhang, Y. A lightweight target detection network: Ghost-YOLONet, Proc. Int. Conf. Remote Sens. Mapping Image Process. (RSMIP), vol. 13167, pp. 868–872, June, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3029829

Hu, R. IoT-based analysis of tennis player’s serving behavior using image processing,Soft Comput., vol. 27, no. 19, pp. 14413–14429, Jul. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-023-09031-w

Vancurik, S. & Callahan, D. W. Detection and identification of choking under pressure in college tennis based upon physiological parameters, performance patterns, and game statistics. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 14 (3), 1942–1953. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2022.3165139 (Jul. 2022).

Niu, M. Research on tennis-assisted teaching assessment technology based on improved dense trajectory algorithm. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 28 (2), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJNVO.2023.133870 (Sep. 2023).

Li, Y. & Wu, L. A wireless self-powered sensor network based on dual-model convolutional neural network algorithm for tennis sports,IEEE Sens. J., vol. 23, no. 18, pp. 20745–20755, Sep. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2023.3255226

Yan, S., Yang, C. & Guo, L. Accuracy improvement in motion tracking of tennis balls using nano-sensors technology. Adv. Nano Res. 14 (5), 409–419. https://doi.org/10.12989/anr.2023.14.5.409 (May. 2023).

Vellela, S. S. et al. Evaluation of tennis teaching effect using optimized DL model with cloud computing system,int. J. Mod. Educ. Comput. Sci. 16 (2), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.5815/ijmecs.2024.02.02 (Apr. 2024).

Li, L. & Yang, A. Correction algorithm of tennis dynamic image serving path based on symmetric algorithm,symmetry. Aug 14 (9), 1833–1834. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14091833 (2022).

Wang, Q. & Yao, N. Light imaging detection based on cluster analysis for the prevention of sports injury in tennis players,opt. Quantum Electron. 56 (2), 191–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-023-05803-8 (Dec. 2024).

Domínguez, G. C., Álvarez, E. F., Córdoba, A. T. & Reina, D. G. A comparative study of machine learning and deep learning algorithms for Padel tennis shot classification,soft comput. Feb 27 (17), 12367–12385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-023-07874-x (2023).

Vives, F., Lázaro, J., Guzmán, J. F., Gallego, R. M. & Crespo, M. Optimizing sporting actions effectiveness: A machine learning approach to uncover key variables in the men’s professional doubles tennis serve,Appl. Sci., vol. 13, no. 24, pp. 13213–13214, Dec. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/app132413213

Yin, L. et al. YOLOV4_CSPBi: Enhanced land target detection model,Land., vol. 12, no. 9, pp. 1813–1814, Sep. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091813

Liu, P., Wang, Q., Zhang, H., Mi, J. & Liu, Y. A lightweight object detection algorithm for remote sensing images based on attention mechanism and YOLOv5s,Remote Sens. Apr 15 (9), 2429–2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15092429 (2023).

Luo, X., Wu, Y. & Wang, F. Target detection method of UAV aerial imagery based on improved YOLOv5,Remote Sens., vol. 14, no. 19, pp. 5063–5067, Sep. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14195063

Yao, J., Fan, X., Li, B. & Qin, W. Oct., Adverse weather target detection algorithm based on adaptive color levels and improved YOLOv5,Sens., 22, 21, pp. 8577–8579, (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/s22218577

Jeong, E. J., Kim, J. & Ha, S. Tensorrt-based framework and optimization methodology for deep learning inference on Jetson boards,acm trans. Embed Comput. Syst. 21 (5), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3508391 (Oct. 2022).

Zhu, C., Qian, J. & Wang, B. YOLOX on embedded device with CCTV & tensorrt for intelligent multicategories garbage identification and classification. IEEE Sens. J. 22 (16), 16522–16532. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2022.3181794 (Aug. 2022).

Li, C., Li, H., Liao, L., Liu, Z. F. & Dong, Y. Jan., Real-time seed sorting system via 2D information entropy‐based CNN pruning and tensorrt acceleration,iet image process., 17, 6, pp. 1694–1708, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1049/ipr2.12747

Abba Haruna, A., Muhammad, L. J. & Abubakar, M. Novel thermal-aware green scheduling in grid environment,artif. Intell. Appl. 1 (4), 244–251. https://doi.org/10.47852/bonviewAIA2202332 (Nov. 2022).

Funding

The research is supported by: Jilin Province Basic Education Teaching Research Topic, Under the background of campus football, Siping City football characteristic school construction problems and countermeasures (No. JLSJY2017G153); Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project of Southwest Medical University, An analysis on the demand and use of elderly care robots in Sichuan Province -- taking Chengdu and Luzhou as examples (No. 2019329).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L.Z. processed the numerical attribute linear programming of communication big data, and the mutual information feature quantity of communication big data numerical attribute was extracted by the cloud extended distributed feature fitting method. B.L. combined with fuzzy C-means clustering and linear regression analysis, the statistical analysis of big data numerical attribute feature information was carried out, and the associated attribute sample set of communication big data numerical attribute cloud grid distribution was constructed. X.L.Z. and B.L. did the experiments, recorded data, and created manuscripts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Li, B. Tennis ball detection based on YOLOv5 with tensorrt. Sci Rep 15, 21011 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06365-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06365-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A lightweight attention-guided multi-scale fusion network for real-time shuttlecock detection

Signal, Image and Video Processing (2026)