Abstract

Chronic hyperglycemia is recognized as an important contributor to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and organ dysfunction that causes serious complications in diabetes and aging. This study investigates the effects of elevated glucose levels on human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hP-MSCs), especially since these cells hold a promise for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine due to their multipotency and self-renewal capabilities. hP-MSCs were treated with 10–40 mM D-glucose to study the effects of high glucose on hP-MSCs functions. hP-MSCs viability and proliferation were determined by using thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT), cell cycle analysis, and senescence assays. The migration and osteogenic differentiation capacity were also determined by migration assay, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity assay, and Alizarin Red S staining. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR, Western blot, and Nanostring® nCounter assay were performed to study the effect of high glucose on the expression levels of genes involved in various aspects of hP-MSCs functions. The results demonstrated that high glucose significantly inhibited proliferation and cell cycle progression of hP-MSCs at the G1/S phase and induced replicative senescence in hP-MSCs possibly by decreasing the expression of proliferation-promoting genes, CCND1 and LMNB1, and increasing the expression of several senescence-associated proteins, p16, p21, and p53. Furthermore, high glucose also inhibited the migration and osteogenic differentiation of hP-MSCs, possibly by suppressing the expression of SDF1, CXCR4, RUNX2, OSX, OCN, and COL1A. The additional Nanostring analysis also showed that high glucose significantly affects multiple genes involved in inflammation, DNA repair, autophagy, and oxidative stress response in hP-MSCs. This study provides significant insights into the wide-ranging effects of high glucose on the expression of the hP-MSCs genes that affect various aspects of its function, including proliferation, viability, senescence, oxidative stress response, and DNA repair, highlighting its implications for regenerative medicine in the context of diabetes and metabolic disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have attracted considerable interest in the fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine because of their ability to differentiate into various cell types and their ability to produce many therapeutically useful factors1. Although a considerable body of evidence demonstrates that MSC therapies possess efficacy in the treatment of various degenerative conditions, such as diabetic wounds, osteoarthritis, severe atopic dermatitis, and chronic ischemic stroke2,3,4,5, the variability in outcomes reported across numerous clinical trials presents a significant barrier to the wider implementation of MSC therapies4. These discrepancies can be attributed to a variety of factors, including the specific biological niche from which MSCs are isolated, the inherent characteristics of the donor, such as age, body mass index, and pre-existing health conditions, the in vitro culture protocols used, and the microenvironment present in the target tissue of the recipients6,7. All of which can profoundly impact the functional capabilities, differentiation potential, and overall therapeutic effectiveness of MSCs.

Hyperglycemia, a high blood glucose prevalent among diabetic patients who underwent MSC therapy, has been shown to induce premature senescence of MSCs derived from bone marrow (BM-MSCs) and adipose tissue and alter their therapeutic potential8,9. Consistent with this observation, MSCs harvested from umbilical cord tissue from mothers with gestational diabetes exhibit premature senescence and mitochondrial dysfunction, thus limiting their application in regenerative medicine10. High glucose levels have been shown to promote the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammatory responses that impair the function of several cell types, including MSCs11,12. Previous findings indicated that hyperglycemia increases tissue inflammation, inhibits osteogenic differentiation of mouse MSCs13, human dental pulp cells14, human gestational tissue-derived MSCs15, and alters chemokine expression in BM-MSCs, which promotes cellular senescence, genomic instability, and telomere attrition16,17,18,19. All of these factors can greatly reduce the therapeutic effectiveness of MSCs in diabetic patients.

Although the existing literature has shown that hyperglycemia affects the therapeutic effects of bone marrow- and adipose-derived MSCs commonly used in MSC therapy, their effects on other sources of MSCs, such as placenta-derived MSCs (hP-MSCs) are not fully understood. hP-MSCs can be harvested in large numbers from discarded placenta tissue by non-invasive procedures, have robust proliferation and differentiation capabilities even after extended culture periods20,21 and can release many therapeutically useful factors, making them more suitable sources for MSC therapies than their bone marrow counterparts. Therefore, this study aims to fill this knowledge gap by investigating the effects of high glucose levels on several important aspects of hP-MSCs functions, including their proliferation, replicative senescence, migration, osteogenic differentiation, and the mechanisms underlying these effects. This knowledge could be used to prevent the deleterious effects of high glucose on MSC functions and improve the viability and therapeutic effects of these MSCs in the treatment of diabetic complications.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of hP-MSCs

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Thammasat University (Medicine) [Approval number: 289/2021]. The placenta was obtained from full-term pregnant women after normal delivery. Written informed consent was obtained from all donors. The hP-MSCs were derived according to the previous study with some modifications15,22. Briefly, placental tissues were minced and partially digested by incubation with 0.5% trypsin–EDTA (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 3 h at 37 °C with continuous shaking. After incubation, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco BRL, USA), resuspended in complete medium [Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 2 mM Glutamax™ (Gibco / Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin], and seeded in a 25 cm2 tissue culture flask (Corning, USA). The cultures were kept at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and the medium was replaced every 3 days for the entire culture period.

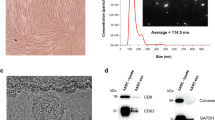

hP-MSCs characterization

hP-MSCs were characterized according to the minimal criteria of the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT)23. The procedure for characterization is as follows:

MSC surface markers

The expression of MSC surface markers was examined using immunostaining with antibodies specific for human antigens, CD34 (BioLegend, USA), CD45 (BioLegend, USA), HLA-DR (BioLegend, USA), CD 73 (BioLegend, USA), CD90 (BD Bioscience, USA) and CD105 (BD Bioscience, USA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, 2×105 hP-MSCs in passages 4-6 were incubated with fluorescent conjugated anti-human antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. The analysis was performed using flow cytometry (CytoFLEX platform for DxFLEX, Beckman Coulter, Life Sciences, USA) and interpreted using CytExpert software.

Differentiation potential of MSCs

To investigate the potential for osteogenic differentiation, hP-MSCs in passages 4-6 were seeded in 6-well plates (Corning, USA) at a density of 5×103 cells/cm2 and cultured in osteogenic induction medium [DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 nM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 µg/mL L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (all Sigma-Aldrich, USA)]. The medium was changed every 3 days and the culture was maintained for 21 days. At the end of the culture, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 20 min, stained with 40 mM Alizarin Red S (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 30 min at room temperature, and observed under an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ts2R-FL, Japan). In some experiments, the extent of Alizarin Red S staining was quantified by lysing the stained cells with 10% acetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at room temperature for 30 min. After centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 min, the supernatant was collected, neutralized with 200 µL of 10% (v/v) ammonium hydroxide, and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek, USA)24,25.

For adipogenic differentiation, hP-MSCs were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5×103 cells/cm2 and cultured in adipogenic induction medium [DMEM, high glucose (DMEM-HG; GibcoBRL, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 500 µM isobutyl methylxanthine, 0.2 mM indomethacin, 1 µM dexamethasone, and 10 µM insulin (all Sigma-Aldrich, USA)]. The medium was changed every 3 days until 21 days. At the end of the culture, cells were fixed with a vapor of 37% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min, stained with 0.3% Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in 60% isopropanol for 20 min, and examined by inverted microscopy.

For chondrogenic differentiation, hP-MSCs in passages 4-6 were seeded at a density of 1×104 cells/well in the center of a 96-well U-bottom plate (Jet Biofil, China) and cultured with MSCgo™ Chondrogenic XF medium (Sartorius, Germany). The medium was changed every 3 days for 21 days. At the end of the culture, cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 10% formaldehyde, stained with a 1% Alcian blue (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution in the dark at room temperature overnight, and then washed three times with 0.1 N hydrochloric acid (HCl). The images were taken with an inverted microscope and a stereo microscope (Nikon SMZ1270, Japan).

Cells cultured with a complete medium served as controls in all differentiation experiments.

Cell viability assay

hP-MSCs were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2 and cultured in a complete medium supplemented with D-glucose (Ajax Finchem Univar® reagent, Australia) to final concentrations of 10 mM, 25 mM, 40 mM, and 100 mM to mimic high glucose conditions as previously described15,26. Cell viability was determined using thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) every 2 days for 14 days. Briefly, cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml MTT for 4 h, at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The formazan precipitate was solubilized in 200 µL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm by a microplate reader. hP-MSCs cultured in a complete medium containing 5.5 mM D-glucose served as control. To exclude the osmolarity effect of glucose, we also cultured hP-MSCs in a complete medium supplemented with D-mannitol (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at the same concentration of D-glucose.

Assessment of growth characteristics

hP-MSCs, passages 3–5, were seeded at a density of 5 × 102 cells/cm2 in 24-well plates (Corning, USA) and cultured in a complete medium supplemented with D-glucose to final concentrations of 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM. hP-MSCs cultured in a complete medium containing 5.5 mM D-glucose served as the control. Cell numbers were determined on culture days 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 using a hemocytometer to generate growth curve. Population doubling time (PDT) was calculated using the following formula27:

where t is the culture time (h), Nt is the harvested cell number, N0 is the initial cell culture number.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR

The hP-MSCs were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 and cultured in a complete medium supplemented with D-glucose to final concentrations of 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM for 7 days. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). cDNA synthesis was performed using the iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR (BioRad, USA) and quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following procedure was used for RT-PCR: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 10 s. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and the expression levels of the target genes were normalized to the endogenous control gene, glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The fold change in relative mRNA expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔct method. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility. The primers are listed in Table 1.

Cell cycle analysis

hP-MSCs were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 and cultured in a complete medium supplemented with D-glucose to final concentrations of 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM for 7 days. Subsequently, 3 × 104 hP-MSCs were then fixed with 0.2 ml of 70% cold ethanol in PBS at − 20 °C for 30 min, washed twice with PBS, incubated with 50 mg/ml of RNase (Merck, Germany) at 37 °C for 30 min, and stained with 50 mg/ml propidium iodide (PI; Merck, Germany) in the dark. Cell cycle analysis was performed using flow cytometry on a CytoFLEX platform for DxFLEX (Beckman Coulter, Life Sciences, USA) with the assistance of CytExpert software. The number of cells in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle was quantified based on previously established methods13. The proliferative index was calculated according to the following equation 28:

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining

hP-MSCs were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 and cultured in a complete medium supplemented with D-glucose to final concentrations of 10 mM, 25 mM and 40 mM for 7 days. At the end of the culture, cells were fixed in a fixative buffer at room temperature for 20 min, washing twice with PBS, incubated with senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining solution (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 16 h at 37 °C, and observed under an inverted microscope. For quantification, six random fields at 100 × magnification were selected and the percentage of senescent cells was calculated as follows29:

Western blot analysis

hP-MSCs were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 and cultured in a complete medium supplemented with D-glucose to final concentrations of 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM for 7 days. Cells were lysed in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (0.05 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 1% TritonX-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.15 M NaCl) containing a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technology, USA) for 20 min on ice and proteins were quantified by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, USA), Proteins were then separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to 0.45 µm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, USA), blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween® 20 (TBST) and 5% skim milk for 2 h, and incubated at 4 °C overnight with appropriate primary antibodies, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit antibody (1:10,000 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch, USA) or goat anti-mouse antibody (1:10,000 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch, USA) for 1.5 h at room temperature. Protein bands were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) using Clarity™ Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad, USA). The signals were quantified with an Amersham ImageQuant 800 (CCD imager) (Amersham imageQuant TL 800, Cytiva, UK) using ImageQuant TL analysis software (IQTL 10.2) and normalized to the intensity of the β-actin band. Antibodies are listed in Table 2.

Scratch wound healing assay

The hP-MSCs were seeded in a 24-well plate and allowed to reach approximately 80% confluence over 24 h in a complete medium. Subsequently, a scratch wound was created across the cell monolayer using a 200 µL pipette tip held perpendicular to the plate, ensuring consistent gap width. The wells were gently washed with PBS to remove debris, and the medium was supplemented with D-glucose to a final concentration of 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM. The wound area was observed at 0, 6, 12, and 24 h using an inverted microscope at 100 × magnification26,30. The percentages of wound closure were calculated using the following equation 31:

A0h = Area of the wound after scratching (t = 0 h).

Axh = Area of the wound at 6, 12, 24 h after the scratching.

Transwell migration assay

2 × 104 hP-MSCs were seeded in the upper chamber of a Transwell plate (8 µm pore size; Millipore, USA) in DMEM containing 5.5 mM D-glucose and 2% FBS. The lower chamber was filled with a complete medium supplemented with D-glucose to final concentrations of 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM. After culture for 24 h, the membranes were fixed in 10% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 15 min, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 20 min at room temperature. Subsequently, cells on the upper membrane surface were removed using a cotton swab, and migrated cells on the lower surface were visualized and quantified using an inverted microscope. For quantification, six random fields at 100 × magnification were analyzed to determine the number of migrated cells. Migration was calculated as follows26:

Osteogenic differentiation assay

The osteogenic differentiation potential of hP-MSCs cultured in a complete medium supplemented with D-glucose to final concentrations of 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM was determined on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 using Alizarin Red S staining and qRT-PCR as above mentioned. In addition, an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity assay was also performed using a SensoLyte® pNPP ALP assay kit (AnaSpec, USA). Cells were lysed using a lysis buffer containing 0.1 M glycine (Bio-Rad, USA), 1% Nonidet P-40 (USB Chemical, USA), 1 mM MgCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 1 mM ZnCl2 (EMSURE®, Germany), pH 9.6, at 4 °C. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 g, 4 °C for 10 min, supernatants were collected and incubated with p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate (pNPP) at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, the stop solution was added and the plate was shaken on a plate shaker for 1 min. The absorbance of the yellow product was detected at 405 nm using a microplate reader. The ALP activity was determined by comparing the optical density (OD) of the samples with a standard curve generated from known concentrations of the ALP standard solution and then normalized to the concentration of total cellular protein.

Nanostring® nCounter assay

hP-MSCs were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 and cultured in a complete medium containing 5.5 mM (control) and 25 mM glucose for 7 days. After treatment, total RNA was isolated using the PureLinkTM RNA Mini Kit (Ambion, USA). A total of 100 ng of RNA was used for nCounter analysis using the nCounter® metabolic pathways panel (NanoString Technologies, USA). An overnight hybridization process was performed at 65 °C with 50-base nCounter Reporter and Capture probes, and the samples were loaded into the nCounter Prep Station. A high-density scan (555 field of view) was then performed on the nCounter Digital Analyzer to enumerate individual fluorescent barcodes and quantify target RNA molecules. Gene expression analysis of 768 genes was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions on the Counter Flex system using the nSolver software v4.0. Gene expression was normalized by the geometric mean of 20 housekeeping genes, with a baseline subtraction threshold count value of 50. Differential expression analysis, using fold-change calculations, compared samples cultured in high glucose with the control. Raw p-values from these analyzes were used to assess differences in gene expression. Heatmaps and related data sets were generated through the nCounter Analysis and Advanced Analysis packages in nSolver 4.0 (NanoString Technologies, USA).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyzes and data visualizations were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0 software (GraphPad Software, USA). Comparisons between the different sample groups were evaluated using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Turkey’s post hoc test. Each assay was performed in triplicate to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the results. Results with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristic of hP-MSCs

hP-MSCs were isolated and characterized according to the standards recommended by the ISCT. On day 2 of culture, the isolated cells displayed a round morphology, with a small number of cells adhering to the culture surface. On day 14 of culture, the hP-MSCs exhibited an elongated shape and proliferated to form a confluent monolayer (Fig. 1A). hP-MSCs also exhibited a trilineage differentiation capacity toward osteoblasts, determined by Alizarin Red S staining, adipocytes, determined by Oil Red O staining, and chondrocytes, determined by Alcian blue staining (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, flow cytometry showed that more than 97% of hP-MSCs expressed typical MSC surface markers, CD73, CD90, and CD105, and did not express hematopoietic surface markers, CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR (Fig. 1B). These results indicated that these hP-MSCs exhibited all of the typical characteristics of the MSCs defined by the ISCT.

Characteristics of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hP-MSCs). (A) Morphology and differentiation potential of hP-MSCs. (a, b) The morphology of hP-MSCs cultured in complete medium on day 2 and day 14. (c, d) hP-MSCs cultured in osteogenic differentiation medium after Alizarin Red S staining compared to the control group cultured in DMEM + 10% FBS. (e, f) hP-MSCs cultured in adipogenic differentiation medium after Oil Red O staining compared to the control group cultured in DMEM + 10% FBS. (g, h) hP-MSCs aggregate cultured in a chondrogenic differentiation medium after Alcian blue staining compared to the control group cultured in DMEM + 10% FBS. (B) Flow cytometry analysis showed the expression of typical MSC surface markers, CD73, CD90, CD105, and the absence of hematopoietic markers, CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR. Images (a, b, g, and h) were captured with a 10 × magnification. Scale bar = 200 µm; Images (c and d) were captured with 4 × magnification. Scale bar = 500 µm; Image e was captured with 20 × magnification. Scale bar = 100 µm; Image (f) was captured with 40 × magnification. Scale bar = 50 µm.

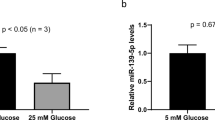

Effect of high glucose on the viability of hP-MSCs

To investigate the effect of high glucose on the survival of hP-MSCs, hP-MSCs were cultured in a complete medium containing four different concentrations of D-glucose (10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM), corresponding to blood sugar levels common in diabetic patients, for 14 days. hP-MSCs cultured in a complete medium containing 5.5 mM glucose, a blood sugar level found in healthy people, served as controls. The results of the MTT assay showed that D-glucose reduced hP-MSCs viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 2A,B). A significant reduction in the viability of hP-MSCs was observed on day 2 in 100 mM D-glucose, the highest glucose concentration initially examined (Fig. 2A). Although 100 mM D-glucose shows the highest level of negative impact, its effects could be caused by an increase in osmolarity rather than the direct effect of D-glucose, as demonstrated by a similar level of viability of hP-MSCs treated with the same concentration of mannitol (Fig. 2A). Therefore, D-glucose concentrations between 10 and 40 mM, which did not show a large osmolarity effect, were chosen for subsequent experiments.

Effect of high glucose on the viability and growth kinetics of hP-MSCs. (A) The MTT assay showed the viability of hP-MSCs treated with 10—100 mM D-glucose for 14 days. hP-MSCs treated with the same concentration of mannitol served as an osmotic control. (B) Phase contrast micrographs of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose compared to control (5.5 mM). (C) Growth kinetics of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose compared to control (5.5 mM). (D) Population doubling (PD) time of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose compared to control (5.5 mM). (E–G) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis demonstrated the expression of stemness genes in hP-MSCs cultured under varying high glucose conditions for 7 days. Normalization of expression levels was conducted relative to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments conducted in triplicate. *p < 0.05 compared to the control. Images B were captured with a 10 × magnification. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Consistent with the MTT results, the growth kinetics revealed that D-glucose reduced growth rates and prolonged the doubling time of hP-MSCs compared to control (5.5 mM D-glucose) in a dose- and time-dependent manner. D-glucose 40 mM had the most significant negative impact on the growth rate and the doubling time of hP-MSCs (Fig. 2C,D). This finding demonstrated that prolonged exposure to high glucose has a cumulative negative effect on the growth and proliferation of hP-MSCs.

Effect of high glucose on stemness of hP-MSCs

To explore how high glucose levels affected stemness, typical characteristics for self-renewal and differentiation into various cell types, the expression of stemness-related genes was explored in hP-MSCs exposed to varying glucose concentrations, 10 mM, 25 mM and 40 mM, compared to control (5.5 mM). qRT-PCR revealed that high glucose conditions negatively impacted the stemness of hP-MSCs, as evidenced by the reduced expression of essential stemness-related genes, OCT4, SOX-2, and NANOG. This effect was dose-dependent, with higher glucose levels leading to greater suppression of self-renewal capacity. A noticeable reduction in OCT4 expression in hP-MSCs was detected across all tested glucose levels compared to the control (Fig. 2E). In particular, SOX-2 and NANOG expression was observed to progressively diminish with increasing glucose levels relative to control conditions (Fig. 2F,G). The gradual decrease in expression suggested that high glucose levels have a dose-dependent suppressive effect on the self-renewal potential of hP-MSCs.

Effect of high glucose on the cell cycle distribution of hP-MSCs

To confirm the inhibitory effect of high glucose on hP-MSCs proliferation, we performed a cell cycle analysis of hP-MSCs treated with 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM D-glucose for 7 days. The results showed that D-glucose inhibited the progression of the hP-MSCs cell cycle in a dose-dependent manner, determined by a significant increase in the percentages of cells in the G0/G1 phase and a decrease in the percentages of cells in both the S and G2/M phases compared to the control (5.5 mM D-glucose) (Fig. 3A,B). D-glucose also significantly reduced the proliferation index, a ratio of actively dividing cells in S and G2/M to total cells, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C; Table 3).

Effect of high glucose on the cell cycle progression of hP-MSCs. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle progression of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose for 7 days compared to control (5.5 mM). (B) Representative histograms show the percentage of hP-MSCs in each phase of the cell cycle. (C) Proliferative index of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose for 7 days compared to control (5.5 mM). (D, E) Graphs show the relative mRNA expression levels of proliferation-promoting genes, CCND1 and LMNB1, in hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose for 7 days compared to control (5.5 mM). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to control (5.5 mM). **p < 0.01 compared to control (5.5 mM).

Consistent with its negative effect on cell cycle progression, D-glucose significantly reduced CCND1 gene expression, a critical regulator of the G1/S transition, and LMNB1, a gene associated with the proliferative state in hP-MSCs, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D,E). These findings suggested that high glucose inhibits the cell cycle progression of hP-MSCs, possibly by down-regulating the expression of proliferation-promoting genes, such as CCND1 and LMNB1, in these cells.

Effect of high glucose on hP-MSCs senescence

To investigate whether the reduced proliferative capacity of hP-MSCs in high glucose is caused by replicative senescence, we determined the percentages of senescence cells by SA-β-gal staining and the expression levels of genes related to senescence. The results showed that exposure to 25 mM and 40 mM D-glucose significantly increases the percentage of SA-β-gal-positive hP-MSCs compared to the control (hP-MSCs treated with 5.5 mM D-glucose) (Fig. 4A,B).

Effect of high glucose on hP-MSCs senescence. (A) Representative micrographs of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose for 7 days compared to control (5.5 mM). (B) Graphs show the percentages of SA-β-gal-positive hP-MSCs after treatment with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose for 7 days compared to control (5.5 mM). (C–E) Graphs show the relative mRNA expression levels of senescence-associated genes (p16, p21, and p53) in hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose for 7 days compared to control (5.5 mM). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 denoting statistical significance relative to control (5.5 mM). Images A were captured with a 10 × magnification. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Consistent with this, the gene expression analysis also showed that 25 mM and 40 mM D-glucose significantly increased the expression levels of senescence-associated genes, p16, p21, and p53, in hP-MSCs compared to the control (Fig. 4C–E). The effect of high glucose on the increased expression of p16, p21, and p53 genes was confirmed by western blot analysis showing that 25 mM and 40 mM D-glucose significantly increased the levels of these three senescence-associated proteins in hP-MSCs compared to the control (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. 1–5). In addition to the increase in senescence-associated proteins, 25- and 40-mM D-glucose also significantly decreased the levels of Cyclin D1 and Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) proteins, which promote growth, proliferation, and longevity, in hP-MSCs (Fig. 5B).

Effect of high glucose on the expression levels of senescent-associated proteins. (A) Western blot shows the levels of proteins involved in cell cycle regulation (Cyclin D1, Sirt1) and senescence (p16, p21 and p53) in hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose for 7 days compared to control (5.5 mM). (B) Graphs show the levels of Cyclin D1, Sirt1, p16, p21, and p53 in hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose for 7 days compared to control (5.5 mM). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to control (5.5 mM).

Collectively, these findings suggested that high glucose induces senescence in hP-MSCs by increasing the expression of various senescence-associated proteins while suppressing the expression of Cyclin D1 and Sirt1 proteins, which promote growth, proliferation, and longevity, in these cells.

Effect of high glucose on hP-MSCs migration

To investigate whether high glucose affects other functional properties of hP-MSCs, we determined the effect of high glucose on the migration of hP-MSCs using scratch wound healing and transwell migration assays. The results show that 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM D-glucose significantly decreased the migration of hP-MSCs, determined by delayed wound closure in the scratch wound healing assay (Fig. 6A,C) and a reduced number of migratory cells in the transwell migration assay (Fig. 6B,D), compared to the control (5.5 mM) in a dose-dependent manner. Consistent with these results, the gene expression study also showed that 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM D-glucose significantly decreased the expression levels of the SDF1 and CXCR4 genes, which have been shown to promote MSC migration (Fig. 6E,F). These results suggested that high glucose levels inhibit hP-MSC migration, possibly by suppressing the expression of migration-promoting genes, such as SDF1 and CXCR4.

Effect of high glucose on hP-MSCs migration. (A) Representative micrographs show the migration of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose compared to control (5.5 mM) at 0, 6, 12, and 24 h, determined by scratch wound healing assays. (B) Representative micrographs show the migration of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose compared to control (5.5 mM) at 16 h, determined by transwell migration assays. (C) Graphs show the percentages of wound closure of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose compared to control (5.5 mM). (D) Graphs show the number of migrated hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose compared to control (5.5 mM), determined by transwell migration assays. (E, F) The graphs show the relative expression levels of the migration-promoting genes, SDF1 and CXCR4, in hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose compared to the control (5.5 mM). Data are presented as means ± SEM from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to the control. Images A and B were captured with a 10 × magnification. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Effect of high glucose on osteogenic differentiation of hP-MSCs

Next, we investigate the effects of high glucose on osteogenic differentiation of hP-MSCs. The results showed that 25 mM and 40 mM D-glucose significantly decreased the osteogenic differentiation of hP-MSCs, determined by reduced levels of Alizarin Red S staining (Fig. 7A,C) and ALP activity (Fig. 7B), compared to the control (5.5 mM D-glucose) in a dose-dependent manner. Consistent with these results, D-glucose also significantly decreased the expression of osteogenic genes, RUNX2, OSX, OCN, and COL1A, in hP-MSCs compared to controls in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7D–G). These findings suggested that high glucose levels inhibit osteogenic differentiation of hP-MSCs, possibly by suppressing the expression of osteogenic genes, such as RUNX2, OSX, OCN, and COL1A, in these cells.

Effect of high glucose on osteogenic differentiation of hP-MSCs. (A) Representative micrographs show the extent of Alizarin Red S staining in hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose at days 7, 14, 21 and 28 of osteogenic differentiation compared to control (5.5 mM). (B) Graphs show the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose at days 7, 14, 21, and 28 of osteogenic differentiation compared to control (5.5 mM). (C) Graphs show the levels of Alizarin Red S staining of hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose at days 7, 14, 21, and 28 of osteogenic differentiation compared to control (5.5 mM). (D–G) Graphs show the relative mRNA expression levels of osteogenic genes, RUNX2, OSX, OCN and COL1A, in hP-MSCs treated with 10, 25, and 40 mM D-glucose at days 7, 14, 21 and 28 of osteogenic differentiation compared to control (5.5 mM). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to control (5.5 mM). **p < 0.01 compared to control (5.5 mM).

Effect of high glucose on the expression of genes involved in DNA repair, oxidative stress response, and autophagy in hP-MSCs

To investigate signaling pathways affected by high glucose levels, a Nanostring® nCounter assay was used to determine the alteration in the expression levels of 725 target genes in hP-MSCs. Hierarchical clustering indicated that 25 mM D-glucose significantly altered the expression of 59 genes in hP-MSCs compared to the control (Fig. 8). These genes included key ligands, receptors and modulators of pathways associated with cell cycle control, autophagy, DNA damage repair, ROS response, and metabolic pathways such as PI3K and mTOR signaling (Fig. 8C). In which, high glucose increased the expression of several genes involved in glutamine metabolism, DNA damage repair, and extracellular matrix-related genes including fms-related receptor tyrosine kinase 1 (FLT1), the alpha-11 integrin (ITGA11), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and collagen type VI alpha 1 chain (COL6A1) (Fig. 8C; Table 4 and Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, high glucose also suppressed the expression of genes associated with cell cycle regulation, lysosomal degradation and DNA damage repair, including interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1), Fanconi anemia, complementation group I (FANCI), and endonuclease specific to the essential structure of meiotic (EME1) in hP-MSCs (Fig. 8C; Table 4 and Supplementary Table 1). These findings suggested that a high glucose level significantly affects multiple signaling pathways, particularly those involved in cellular senescence, autophagy, and oxidative stress in hP-MSCs.

NanoString nCounter analysis shows the effect of high glucose on the gene expression profile of hP-MSCs. (A) Heatmap of the hierarchical cluster analysis shows the gene expression profiles of hP-MSCs treated with 25 mM D-glucose for 7 days compared to control (5.5 mM). (B) Volcano plot shows genes that are upregulated under high glucose conditions. Notable examples include FLT1, ITGA11, VEGFA, and COL6A1, which are involved in glutamine metabolism and DNA damage repair. Data represent fold changes determined by NanoString nCounter analysis, with p-values indicating statistical significance compared to the control (5.5 mM). (C) Gene enrichment analysis shows significantly up- and down-regulated genes under high glucose conditions.

Discussion

Although chronic hyperglycemia is recognized as an important contributor to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and organ dysfunction, which causes serious complications in type 2 diabetes19 and the aging process16, its effects on MSC functions remain underexplored. MSCs were isolated from human placenta and characterized according to the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) guidelines. All three differentiation potentials were conducted under normal glucose conditions to confirm MSC characteristics. The effects of high glucose on the proliferation, migration, and osteogenic differentiation of hP-MSCs were investigated using glucose concentrations of 10 mM, 25 mM, and 40 mM. 5.5 mM (100 mg/dL) D-glucose represents a normal blood glucose level, while 10 mM (180 mg/dL) D-glucose represents a level of blood glucose in diabetic patients with good glycemic control, which allows us to investigate how hP-MSCs respond to mild disturbances in glucose metabolism. 25 mM (450 mg/dL) D-glucose represents a level of blood glucose in diabetic patients with poor glycemic control, allowing us to investigate the response of hP-MSCs under conditions that induced long-term diabetic complications. The highest concentration of 40 mM (720 mg / dL) of D-glucose represents a level of blood glucose in diabetic patients during acute diabetic crises, such as diabetic hyperosmolar syndrome, which allows us to investigate the effects of extremely high glucose on hP-MSCs. Using this range of glucose concentrations, our objective is to investigate how varying levels of hyperglycemia affect the proliferation, migration, and osteogenic differentiation of hP-MSCs, which could improve our understanding of the mechanisms underlying hyperglycemic-induced diabetic complications.

Our results revealed that high glucose reduced viability, decreased growth rates, and prolonged the doubling time of hP-MSCs in a dose- and time-dependent manners, which is similar to previous studies showing that high glucose impairs the growth of various stem cell populations14,18. High glucose suppressed the expression of stemness markers such as OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG. Specifically, OCT4 expression decreased progressively under high glucose conditions, particularly at 40 mM glucose. The significant reductions in SOX2 and NANOG mRNA levels at high glucose concentrations further underscore this trend. Previous studies have highlighted the interdependence of OCT4 and SOX2 in maintaining stemness, with OCT4 being linked to increased osteogenic marker expression in MSCs derived from human adipose tissue32. Furthermore, upregulation of OCT4 and NANOG has been associated with enhanced trilineage differentiation potential and proliferation, indicating their crucial role in preserving MSC characteristics33. SOX2 is essential for maintaining both the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation capabilities of MSCs. For instance, human BM-MSCs expressing SOX2 established improved proliferation and osteogenic differentiation potential when cultured with basic fibroblast growth factor34. In contrast, SOX2-knockout MSCs exhibited a senescent phenotype, leading to impaired colony-forming ability35. We also showed that high glucose reduced hP-MSCs proliferation by inhibiting its cell cycle progression, possibly by downregulating the expression of CCND1, LMNB1, and SIRT1, which promote cell growth, proliferation, and cellular longevity36,37.

Furthermore, high glucose also induces replicative senescence in hP-MSCs, characterized by an increase in β-galactosidase-positive cells and an increase in the expression of several senescence-associated proteins, p16, p21, and p53. Our finding is consistent with previous studies showing that high glucose (25–40 mM D-glucose) increased levels of p16, p21, and p53 proteins in human renal tubular epithelial cells and endothelial cells38,39, and another study showing that umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) isolated from patients with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) exhibit accelerated senescence and express higher levels of p53 and p1640. Our study supports findings of previous studies showing that high glucose induces senescence in several types of cells18,19,41 by activating the p53 and pRb pathways, which up-regulates cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, p21 and p16, causing cell cycle arrest42,43.

In addition to its effect on cell proliferation, high glucose also negatively affects the function of hP-MSCs by reducing their migration capacity, possibly through downregulation of the migration-promoting CXCR4 and SDF1 genes44,45,46. Although some previous studies indicated that high glucose promotes migration of some cancer cells47, our results are consistent with other studies showing that high glucose reduces migration of neural crest cells and rat BM-MSCs41,48. The discrepancy is probably caused by differences in the cell types used in each study. Furthermore, high glucose levels also inhibit osteogenic differentiation of hP-MSCs, possibly by suppressing the expression of osteogenic genes, RUNX2, OSX, OCN, and COL1A, which play a significant role in the osteogenic differentiation process49,50. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that high glucose inhibits osteogenic differentiation and matrix mineralization of BM-MSCs, UC-MSCs and human dental pulp stem cells13,15,51.

Our high-throughput gene expression analysis using Nanostring® nCounter assay also showed that high glucose decreased the expression of genes involved in DNA damage repair (FANCI, EME1 and FANCA), oxidative stress response (SOD2 and HMOX1), and autophagy52 in hP-MSCs. Down-regulation of these genes could increase the susceptibility of hP-MSCs to DNA damage and oxidative stress that could result in reduced proliferation, increased senescence, and increased apoptosis53. Furthermore, high glucose also increased the expression of genes involved in inflammation and immune responses, such as FLT1, ITGA11, and VEGFA, and the matrix-related gene COL6A1, which has been shown to promote cellular senescence and tissue fibrosis54,55.

The findings from this study enhance the current understanding of the effects of high glucose exposure by integrating gene expression analysis through Nanostring technology. This approach elucidates the metabolic pathways influenced by elevated glucose levels. Furthermore, it highlights the transcriptional and translational regulation of senescence markers, thereby providing a deeper insight into the dysfunction of MSCs in hyperglycemic conditions. These results lay the groundwork for developing targeted strategies to mitigate high glucose-induced MSC dysfunction and its implications for degenerative diseases in the future.

Conclusions

This study elucidates the profound impact of high glucose levels on the functionality of hP-MSCs. Our findings demonstrate that elevated glucose concentrations significantly impair hP-MSCs proliferation, induce replicative senescence, and hinder both migration and osteogenic differentiation. These effects are mediated through alterations in gene expression, including the downregulation of proliferation-related genes and the upregulation of senescence markers. Additionally, high glucose influences a range of genes associated with inflammation, DNA repair, autophagy, and oxidative stress response. Collectively, these insights underscore the critical implications of hyperglycemia for the therapeutic potential of hP-MSCs in regenerative medicine, particularly in the context of diabetes and related metabolic disorders. Understanding these mechanisms may help create strategies to enhance the efficacy of hP-MSCs in clinical applications. Although beyond the scope of the present study, we suspect that high glucose could also affect the adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs and plan to study the effect of high glucose on these aspects to improve our understanding of the complex effects of hyperglycemia on mesenchymal stem cells in the future.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BM-MSCs:

-

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- CCND1:

-

Cyclin D1

- CD:

-

Cluster of differentiation

- cDNA:

-

Complementary DNA

- COL1A:

-

Collagen 1 A

- COL6A1:

-

Collagen type VI Alpha 1 chain

- CXCR4:

-

CXC Chemokine receptor type 4

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EME1:

-

Essential meiotic structure-specific endonuclease 1

- FANCI:

-

Fanconi anemia, complementation group I

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- FLT1:

-

FMS-related receptor tyrosine kinase 1

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- HRP:

-

Horseradish peroxidase

- IRF1:

-

Interferon regulatory factor 1

- ISCT:

-

International society for cell & gene therapy

- ITGA11:

-

Integrin alpha-11

- LMNB1:

-

Lamin-B1

- MSCs:

-

Mesenchymal stem cells

- MTT:

-

3-[4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- NANOG:

-

NANOG homeobox

- OD:

-

Optical density

- OCN:

-

Osteocalcin

- OSX:

-

Osterix

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PE:

-

Phycoerythrin

- PI3K:

-

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- hP-MSCs:

-

Human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- pNPP:

-

p-Nitrophenyl phosphate

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- RIPA:

-

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay

- RUNX2:

-

Runt-related transcription factor 2

- SA-β-Gal:

-

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining

- SDF1:

-

Stromal cell-derived factor 1

- SDS-PAGE:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- SOX2:

-

SRY-box transcription factor 2

- TBST:

-

Tris-buffered saline with tween® 20 detergent

- UC-MSCs:

-

Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- VEGFA:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor A

- ΔΔCT:

-

Comparative threshold cycle

References

Margiana, R. et al. Clinical application of mesenchymal stem cell in regenerative medicine: A narrative review. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 13, 366. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-022-03054-0 (2022).

Kurniawan, M. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells therapy for chronic ischemic stroke-a systematic review. Asian Biomed. (Res. Rev. News) 18, 194–203. https://doi.org/10.2478/abm-2024-0027 (2024).

Seo, H. M. et al. Phase 1/2 trials of human bone marrow-derived clonal mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 154, 965–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2024.06.013 (2024).

D’Arrigo, D., Salerno, M., De Marziani, L., Boffa, A. & Filardo, G. A call for standardization for secretome and extracellular vesicles in osteoarthritis: Results show disease-modifying potential, but protocols are too heterogeneous-a systematic review. Hum. Cell 37, 1243–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13577-024-01084-9 (2024).

Ashoobi, M. T. et al. Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells transplantation for critical limb ischemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A preliminary report of phase I clinical trial. Cell Tissue Res. 395, 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-023-03854-7 (2024).

Costa, L. A. et al. Functional heterogeneity of mesenchymal stem cells from natural niches to culture conditions: Implications for further clinical uses. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 78, 447–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-020-03600-0 (2021).

Li, J. et al. The heterogeneity of mesenchymal stem cells: An important issue to be addressed in cell therapy. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 14, 381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-023-03587-y (2023).

Badr, O. I., Kamal, M. M., El-Maraghy, S. A. & Ghaiad, H. R. The effect of diabetes mellitus on differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into insulin-producing cells. Biol. Res. 57, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40659-024-00502-4 (2024).

Yin, M., Zhang, Y., Yu, H. & Li, X. Role of hyperglycemia in the senescence of mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 665412. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.665412 (2021).

Salem, S. & Leach, L. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells from gestational diabetes show impaired ability to up-regulate paracellular permeability from sub-endothelial niche. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 138, 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20230657 (2024).

Fiorentino, T. V., Prioletta, A., Zuo, P. & Folli, F. Hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and its role in diabetes mellitus related cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 5695–5703. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612811319320005 (2013).

Zhang, Z. et al. The impact of oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction on diabetic microvascular complications. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 14, 1112363. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1112363 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. High glucose inhibits osteogenic differentiation through the BMP signaling pathway in bone mesenchymal stem cells in mice. EXCLI J. 12, 584–597 (2013).

Horsophonphong, S., Kitkumthorn, N., Sritanaudomchai, H., Nakornchai, S. & Surarit, R. High glucose affects proliferation, reactive oxygen species and mineralization of human dental pulp cells. Braz. Dent. J. 31, 298–303. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440202003120 (2020).

Hankamolsiri, W. et al. The effects of high glucose on adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of gestational tissue-derived MSCs. Stem. Cells Int. 2016, 9674614. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9674614 (2016).

Yin, M., Zhang, Y., Yu, H. & Li, X. Role of hyperglycemia in the senescence of mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 665412. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.665412 (2021).

Chang, T. C., Hsu, M. F. & Wu, K. K. High glucose induces bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell senescence by upregulating autophagy. PLoS ONE 10, e0126537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126537 (2015).

Al-Qarakhli, A. M. A., Yusop, N., Waddington, R. J. & Moseley, R. Effects of high glucose conditions on the expansion and differentiation capabilities of mesenchymal stromal cells derived from rat endosteal niche. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12860-019-0235-y (2019).

Rharass, T. & Lucas, S. High glucose level impairs human mature bone marrow adipocyte function through increased ROS production. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 10, 607. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00607 (2019).

Manochantr, S. et al. Immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stromal cells derived from amnion, placenta, Wharton’s jelly and umbilical cord. Intern. Med. J. 43, 430–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12044 (2013).

Barlow, S. et al. Comparison of human placenta- and bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stem cells. Stem. Cells Dev. 17, 1095–1107. https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2007.0154 (2008).

Thaweesapphithak, S. et al. Human serum enhances the proliferative capacity and immunomodulatory property of MSCs derived from human placenta and umbilical cord. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 10, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-019-1175-3 (2019).

Dominici, M. et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 8, 315–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14653240600855905 (2006).

Jeon, J., Lee, M. S. & Yang, H. S. Differentiated osteoblasts derived decellularized extracellular matrix to promote osteogenic differentiation. Biomater. Res. 22, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40824-018-0115-0 (2018).

Gregory, C. A., Gunn, W. G., Peister, A. & Prockop, D. J. An Alizarin red-based assay of mineralization by adherent cells in culture: Comparison with cetylpyridinium chloride extraction. Anal. Biochem. 329, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2004.02.002 (2004).

Kim, G. D. & Park, S. Effects of Cudrania tricuspidata on anti-senescence in high glucose-treated endothelial cells via the Akt/p53/p21 pathway. Food Sci. Nutr. 8, 5999–6006. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1885 (2020).

Ramarao, K. D. R. et al. Antiproliferative effects of dried Moringa oleifera leaf extract on human Wharton’s Jelly mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS ONE 17, e0274814. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274814 (2022).

Zeng, X. et al. TMEM16A regulates portal vein smooth muscle cell proliferation in portal hypertension. Exp. Therapeutic Med. 15, 1062–1068. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.5466 (2017).

Suwanmanee, G., Tantrawatpan, C., Kheolamai, P., Paraoan, L. & Manochantr, S. Fucoxanthin diminishes oxidative stress damage in human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells through the PI3K/Akt/Nrf-2 pathway. Sci. Rep. 13, 22974. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49751-5 (2023).

Liao, N. et al. Antioxidants inhibit cell senescence and preserve stemness of adipose tissue-derived stem cells by reducing ROS generation during long-term in vitro expansion. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 10, 306. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-019-1404-9 (2019).

Vivcharenko, V., Wojcik, M. & Przekora, A. Cellular response to vitamin C-enriched chitosan/agarose film with potential application as artificial skin substitute for chronic wound treatment. Cells 9, 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9051185 (2020).

Han, S. M. et al. Enhanced proliferation and differentiation of Oct4- and Sox2-overexpressing human adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 46, e101. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2014.28 (2014).

Tsai, C. C., Su, P. F., Huang, Y. F., Yew, T. L. & Hung, S. C. Oct4 and Nanog directly regulate Dnmt1 to maintain self-renewal and undifferentiated state in mesenchymal stem cells. Mol. Cell 47, 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.020 (2012).

Go, M. J., Takenaka, C. & Ohgushi, H. Forced expression of Sox2 or Nanog in human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells maintains their expansion and differentiation capabilities. Exp. Cell Res. 314, 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.11.021 (2008).

Yoon, D. S., Kim, Y. H., Jung, H. S., Paik, S. & Lee, J. W. Importance of Sox2 in maintenance of cell proliferation and multipotency of mesenchymal stem cells in low-density culture. Cell Prolif. 44, 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2184.2011.00770.x (2011).

Shimi, T. et al. The role of nuclear lamin B1 in cell proliferation and senescence. Genes Dev 25, 2579–2593. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.179515.111 (2011).

Basmaeil, Y. et al. Preconditioning of human decidua basalis mesenchymal stem/stromal cells with glucose increased their engraftment and anti-diabetic properties. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 17, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13770-020-00239-7 (2020).

Ramini, D. et al. Replicative senescence and high glucose induce the accrual of self-derived cytosolic nucleic acids in human endothelial cells. Cell Death Discovery 10, 184. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-024-01954-z (2024).

Eleftheriadis, T. et al. Dapagliflozin prevents high-glucose-induced cellular senescence in renal tubular epithelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 16107. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232416107 (2022).

Kim, J. et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells affected by gestational diabetes mellitus display premature aging and mitochondrial dysfunction. Stem. Cells Dev. 24, 575–586. https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2014.0349 (2015).

Zhang, B. et al. High glucose microenvironments inhibit the proliferation and migration of bone mesenchymal stem cells by activating GSK3beta. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 34, 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-015-0662-6 (2016).

Turano, P. S. & Herbig, U. Cellular senescence, p21, and the path to fibrosis. EMBO J. 43, 5332–5334. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44318-024-00245-8 (2024).

Kumari, R. & Jat, P. Mechanisms of cellular senescence: Cell cycle arrest and senescence associated secretory phenotype. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 645593. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.645593 (2021).

Gong, J. et al. The SDF-1/CXCR4 axis regulates migration of transplanted bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells towards the pancreas in rats with acute pancreatitis. Mol. Med. Rep. 9, 1575–1582. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2014.2053 (2014).

Miller, R. J., Banisadr, G. & Bhattacharyya, B. J. CXCR4 signaling in the regulation of stem cell migration and development. J. Neuroimmunol. 198, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.008 (2008).

Liu, X. et al. SDF-1 promotes endochondral bone repair during fracture healing at the traumatic brain injury condition. PLoS ONE 8, e54077. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054077 (2013).

Takatani-Nakase, T., Matsui, C., Maeda, S., Kawahara, S. & Takahashi, K. High glucose level promotes migration behavior of breast cancer cells through zinc and its transporters. PLoS ONE 9, e90136. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090136 (2014).

Suzuki, N., Svensson, K. & Eriksson, U. J. High glucose concentration inhibits migration of rat cranial neural crest cells in vitro. Diabetologia 39, 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00400671 (1996).

Cao, B., Liu, N. & Wang, W. High glucose prevents osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via lncRNA AK028326/CXCL13 pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother 84, 544–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2016.09.058 (2016).

Ahmadi, A. et al. Recent advances on small molecules in osteogenic differentiation of stem cells and the underlying signaling pathways. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 13, 518. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-022-03204-4 (2022).

Kichenbrand, C., Grossin, L., Menu, P. & Moby, V. Behaviour of human dental pulp stem cell in high glucose condition: Impact on proliferation and osteogenic differentiation. Arch. Oral. Biol. 118, 104859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104859 (2020).

Oh, S. J. & Lee, M. S. Role of autophagy in the pathogenesis of diabetes and therapeutic potential of autophagy modulators in the treatment of diabetes and metabolic syndrome. J. Korean Med. Sci. 37, e276. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e276 (2022).

Su, H., Wang, Z., Zhou, L., Liu, D. & Zhang, N. Regulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis by mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles: Implications for disease treatment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 1397954. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2024.1397954 (2024).

O’Reilly, S., Tsou, P. S. & Varga, J. Senescence and tissue fibrosis: Opportunities for therapeutic targeting. Trends Mol. Med. 30, 1113–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2024.05.012 (2024).

Youssef, A., Aboalola, D. & Han, V. K. The roles of insulin-like growth factors in mesenchymal stem cell niche. Stem. Cells Int. 2017, 9453108. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9453108 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the delivery room, Thammasat University Hospital, for facilitating the specimen collection, and all volunteers for kindly donating tissues for this study. The authors declare that they have not used AI-generated work in this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fundamental Fund fiscal year 2024, Thammasat University (Grant No.TUFF 52/2567), the Center of Excellence in Stem Cell Research and Innovation, Thammasat University. The funding body played no role in the design of the study and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, nor in the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SD conducted the experiments and drafted the manuscript. CT contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. PK contributed to the data interpretation and revised the manuscript. SM contributed to conceptualization, study design, resources, supervision, data analysis and interpretation, draft, and completed manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All experimental procedures were conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Thammasat University (Medicine) [Approval title: Effects of high glucose condition on survival capability and osteogenic differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells.] [Approval number: 289/2021] (Date of approval: November 3, 2021). All samples were obtained from donors with their written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duangprom, S., Kheolamai, P., Tantrawatpan, C. et al. High glucose inhibits proliferation, migration, and osteogenic differentiation of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep 15, 22512 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06454-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06454-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Photobiomodulation stimulates mitochondrial function and cell proliferation in meniscus-derived stem cells (MeSCs) via activation of TRPV1 channel

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Comprehensive bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing uncovers senescence-associated biomarkers in therapeutic mesenchymal stem cells

Scientific Reports (2025)