Abstract

Drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction is a critical task in computational drug discovery, enabling drug repurposing, precise medicine, and large-scale virtual screening. Traditional in-silico methods, such as molecular docking, classical machine learning, and deep learning, have made significant progress in addressing this issue. However, existing approaches are hindered by computational inefficiencies, reliance on manual feature engineering, and struggles to generalize across diverse molecular structures, limiting their molecular capabilities. Recent advancements in Quantum Machine Learning (QML) are paving the way for its practical applications, unlocking unprecedented capabilities in predictive accuracy, scalability, and efficiency by leveraging the unique powers of quantum computing, namely superposition and entanglement. This study proposes QKDTI - Quantum Kernel Drug-Target Interaction, a novel quantum-enhanced framework for DTI prediction. It used Quantum Support Vector Regression (QSVR) with quantum feature mapping that takes into account a quantum feature space for molecular descriptors and allows encoding molecular and protein features, improved predictions of binding affinities. To enhance the model to be more computationally feasible, integration of the Nystrom approximation into the model allows providing an efficient kernel approximation while reducing overhead expenses. QKDTI was evaluated on benchmark datasets - Davis and KIBA, and validated independently on BindingDB. This model achieves 94.21% accuracy on DAVIS, 99.99% on KIBA, and 89.26% on BindingDB, significantly outperforming classical and other quantum models. Further, the statistical tests have been conducted on the compared models to provide the reliability of the results. This indicates that introducing quantum computing into DTI pipeline can revolutionize computational drug discovery by improving predictive accuracy and providing a better generalization over multiple datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DTI prediction is a fundamental aspect of computational drug discovery, identifying how small molecules interact with biological macromolecule targets like proteins, enzymes, receptors, etc1. Understanding these drug interactions is crucial for pharmacology to identify therapeutic effects, unwanted side effects, and toxic potencies of drug compounds. High-throughput screening has been widely used to examine binding interactions. However, these methods are time-consuming and expensive, particularly when dealing with the vast number of potential combinations. The exploration of modern techniques can speed up drug candidate testing before clinical trials2.

Traditional In-silico methods for DTI prediction include molecular docking, machine learning (ML), and deep learning models (DL). While these methodologies have shown potential results, they come with inherent challenges. Molecular docking simulations are computationally expensive and frequently fail to scale across diverse chemical structures. Classical models rely on feature engineering and require huge knowledge to extract accurate representations of molecules and proteins3. DL has improved automatic feature extraction but requires large labeled datasets, which are often scarce in drug discovery. Moreover, these models struggle with high-dimensional molecular data and the complexity of biochemical interactions, which limits their ability to generalize across different drug classes and target proteins4.

Recent evolutions in quantum computing have introduced new possibilities in computational drug discovery, particularly in quantum machine learning (QML). Quantum computing (QC) has the potential to process high-dimensional data more effectively by leveraging quantum superposition and entanglement, allowing faster and more complex calculations that classical computers would struggle to handle5. Unlike classical models that rely on predefined feature spaces, quantum models can encode molecular and protein features into quantum states, capturing better structural and interaction information. This capability alleviates predictive performance, better generalization, and improved efficiency in DTI tasks6. This study is motivated by the growing demand for contemporary computational approaches that can tackle the limitations of existing DTI prediction models. While DL has endorsed a significant rise over traditional ML models, it has some challenges related to scalability, interpretability, and data efficiency. QML and hybrid models provide an alternative by combining quantum feature embedding and quantum kernels, possibly giving better drug target affinity prediction.

Research questions

RQ1 - Can quantum computing improve the performance of drug-target interaction predictions?

RQ2 - How does quantum computing’s performance compare to classical approaches in terms of efficiency?

RQ3 - How does quantum computing handle complex biochemical data compared to classical methods?

By delving into these questions, this study explores the following research objectives.

Objectives of the study

This study intended to develop and evaluate a quantum-enhanced machine learning framework for DTI prediction, focusing on its practical feasibility in drug discovery. The specific objectives are:

-

To develop a quantum-enhanced framework for predicting drug-target interactions by integrating quantum computing principles with classical ML techniques.

-

To compare the performance of quantum machine learning models and classical machine learning models in terms of accuracy, efficiency, and predictive reliability.

-

To analyze the ability of quantum computing to handle high dimensional data, mainly in representing molecular structures and protein-ligand interactions.

By addressing these objectives, this study contributes to the evolving field of quantum drug discovery, providing visions of how quantum computing can transform the landscape of computational pharmaceutical research.

This study provides a novel quantum kernel-based regression framework (QKDTI) that integrates a quantum support vector regression model with the computed Nystrom approximation kernels, which is not been explored previously for the datasets KIBA, DAVIS, and Binding DB. The proposed model transforms the classical biochemical features into the quantum Hilbert spaces using parameterized RY and RZ-based quantum circuits, capturing non-linear biochemical interactions through quantum entanglement and inference where whereas the classical machine learning on shallow kernels and deep learning models rely on neural networks. Technically, this model overcomes scalability limitations by using a batched and parallel quantum kernel computation pipeline, enabling efficient processing of molecular samples. This architecture allows a quantum kernels integrated into a classical pipeline, combining quantum-enhanced features with robustness and interpretability of classical algorithms. This provides a computationally efficient, generalizable model that maintains high performance across all the real-world datasets. This framework provides a draught for future quantum-classical hybrid models in drug discovery, which bridges theoretical advancements in QML with practical biomedical applications. The findings could improve precision medicine, drug repurposing, and large-scale drug screening, making it a valued step towards incorporating quantum computing into biomedical applications.

Literature review

Over the years, computational methods have played an important role in the drug discovery process. One crucial task in this process is predicting DTI. Methods like classical ML and DL have been used for this purpose.

Molecular docking is one of the earliest computational processes developed to predict binding interactions between drug molecules and proteins. It is performed by simulating the physical and chemical interactions between molecules, directing to quote the binding affinity of a drug to its target. Although docking gave impressive results, it struggles with flexible molecular structures, which may lead to inaccurate predictions and the process is computationally expensive. To cover these issues, ML and DL models are introduced to improve DTI predictions7.

Machine learning models

Classical ML models like support vector machines (SVM), random forest (RF), and K-nearest neighbors have been used in the DTI prediction. These models performed well on structured datasets, and their dependence on feature engineering made them less adaptable to complex and high-dimensional biochemical data.

SVMs are supervised learning models that classify data by finding the optimal hyperplane separating different classes. In DTI prediction, SVM has been utilized to distinguish between interacting and non-interacting drug–target pairs by mapping input features into high-dimensional spaces. However, their performance heavily depends on the quality of feature engineering and the selection of appropriate kernels, which can be challenging when dealing with complex biochemical data8. RFs are ensemble learning methods that construct multiple decision trees during training and output the mode of the classes for classification tasks9. They have been employed in DTI prediction to handle large datasets and model nonlinear relationships. Despite their robustness, RFs require extensive feature engineering to effectively capture the intricacies of molecular interactions, limiting their adaptability to high-dimensional data10. The k-NN algorithm classifies data points based on the majority class among their k-nearest neighbors in the feature space. In the context of DTI prediction, k-NN has been applied to predict interactions by assessing the similarity between drug and target features. However, k-NN’s reliance on distance metrics makes it sensitive to the curse of dimensionality, posing challenges when dealing with complex molecular descriptors. While these traditional ML models have achieved success with structured datasets, their dependence on manual feature extraction limits their scalability and effectiveness in capturing the multifaceted nature of drug–target interactions. This limitation has led to the exploration of DL approaches, which can automatically learn feature representations from raw data, thereby enhancing the prediction accuracy of DTI.

Deep learning models

DL is another impressive method used for DTI prediction that addresses the limitations caused by classical machine learning models, like automating feature extraction and learning large molecular patterns. DL uses techniques like representation learning, which allows for extracting suitable, meaningful features directly from the raw input data. Some of the DL approaches like convolutional neural network11, long short-term memory12, and graph convolutional network13 has been applied to the DTI tasks, which improved the performance. Methods such as Deep DTI14 introduced an unsupervised refined molecular representation before classification, outperforming traditional ML models. PADME (Protein And Drug Molecule interaction prEdiction)15 used deep neural networks combined with molecular graph convolutions to address complex problems where novel drug-target pairs had no subsequent interaction data, thus improving generalization. DL models require vast datasets to attain optimal performance, and their black-box nature raises challenges in interpretability, limiting their direct adoption in clinical applications16,17. One of the studies18 introduced a deep ensemble model that integrates diverse neural networks across multiple datasets, achieving robust performance. Similarly19, proposed global local hybrid approach that used contextual embedding to combine protein sequence with substructure molecular features. Another advanced study20 represents a molecule representation block using multi-head attention and skip connections, capturing local and long-range dependencies. As DL pushes the boundaries of DTI prediction, researchers are exploring quantum computing as a novel approach to overcome the challenges posed by classical machine learning and DL methods.

Quantum models

Quantum computing is powerful due to features like superposition and entanglement, which allow it to process complex and high-dimensional interactions more effectively. These features can encode the molecular and protein features into quantum states, allowing better representation of interactions. Recent studies introduced quantum machine learning techniques, such as quantum kernels, variational quantum circuits (VQC), and hybrid quantum models, to enhance DTI prediction21. Quantum feature mapping enhances molecular interaction calculations, improving affinity predictions compared to classical kernel methods. One of the earliest applications of quantum computing in DTI involved VQC, which demonstrated competitive performance in classifying drug-protein interactions. In one study, a quantum-enhanced classification model achieved a concordance index of 0.802, surpassing traditional linear regression methods and DL models. The ability of quantum models to optimize hyperparameters like qubit count and circuit depth further enhances their adaptability to complex biochemical data. Beyond classification, quantum computing has been integrated into binding affinity prediction, focusing on challenges like convergence stability and accuracy. A hybrid quantum-classical framework featuring 3D and spatial graph convolutional neural networks was proposed to improve affinity prediction, yielding a 6% increase in all the metrics (R2, MAE, Pearson, Spearman, RMSE) over classical models. To ensure scalability on current NISQ devices, quantum error mitigation techniques have been introduced to effectively reduce errors without computational overhead22.

Table 1 provides a summary of the DTI prediction and bioinformatics modeling incorporating three computing paradigms: classical machine learning, deep learning, and quantum computing. Existing models exhibit limitations, which include dependency on feature engineering, limited generalizability issues under high-dimensional settings. DL models are more powerful than ML, which suffer from interpretability challenges, while quantum models remain constrained by hardware capabilities and are typically restricted to small molecules. The binary classification approaches fail to capture the continuous nature of binding affinities. The proposed model addresses these challenges through a hybrid model that uses quantum-enhanced feature representation by integrating both sequence and structural modalities with quantum kernels. This model enhances predictive accuracy and generalizability that enabling regression-based affinity estimation and improved interpretability. This positions our approach as a robust and scalable solution in the evolving landscape of quantum-assisted drug discovery. Upcoming research is expected to improve quantum feature encoding, optimize hybrid models, and address hardware limitations, paving the way for quantum-enhanced precision medicine.

Methodology

This study proposed QKDTI - Quantum Kernel Drug-Target Interaction, a novel quantum-enhanced regression framework for DTI prediction that enhance the accuracy and efficiency of Drug-Target Interaction prediction. By leveraging quantum kernels, QKDTI captures complex molecular interactions more effectively than classical machine-learning approaches.

Traditional methods, such as classical ML and DL approaches, struggle with high-dimensional feature spaces, computational inefficiencies, and nonlinear interactions between molecular structures. SVR is a widely used machine learning technique for predicting continuous values, particularly in scenarios where the relationship between input features and output is complex and nonlinear. Traditional SVR relies on kernel functions such as linear, polynomial, and radial basis function kernels to project data into a higher-dimensional space where a linear regression model can be fit.

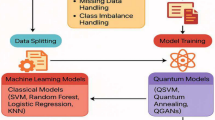

QKDTI provides an alternative approach by utilizing quantum kernels to map complex molecular interactions into higher-dimensional Hilbert spaces43, capturing non-linearity more effectively than classical models. Unlike classical kernels, quantum kernels utilize quantum superposition and entanglement to capture intricate molecular structures and protein-ligand interactions more efficiently. This allows QKDTI to handle non-linearity in drug-target binding affinity predictions with improved precision. This study investigates the capability of quantum kernel learning for predicting binding affinity values in drug discovery applications. The methodology incorporates quantum-enhanced feature transformations with quantum machine learning techniques to optimize performance. The proposed framework consists of the following steps as shown in Fig. 1.

Dataset description

This study is based on datasets from the Therapeutics Data Commons: a widely used source of curated datasets for drug discovery34. Among its extensive collection, three widely used datasets DAVIS, KIBA, and BindingDB were selected for training, testing, and validation of the proposed model. These datasets were retrieved using the TDC Python library interface, specifically from the multi-prediction DTI task module. Each dataset includes drug-target pairs along with their measured binding affinities, reported using experimental metrics such as Kd, IC50, Ki or integrated scores like the KIBA score.

Molecular Representations.

-

Drugs - Small Molecules: Represented using SMILES - Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System strings, a text-based encoding of molecular structure.

-

Targets - Proteins: Represented using FASTA sequences, encoding the amino acid sequence of each protein target.

To prepare the raw molecular and protein data for machine learning models:

-

Molecular fingerprints44,45 or learned embeddings are derived from SMILES using RDKit cheminformatics tools.

-

Protein features are extracted via pre-trained models or sequence-based descriptors like ProtBERT or physicochemical proper encodings.

Each dataset includes experimentally determined binding affinity values:

-

DAVIS: Reports binding affinities in Kd (nM), specifically for kinase inhibitors.

-

KIBA: Provides KIBA Scores, which are normalized affinity scores integrating multiple biochemical measurements.

-

BindingDB: Includes a wide range of binding values reported as Kd, IC50, or Ki in nM, µM, or mM units.

The Binding affinity measurements and units are observed in Table 2.

Due to this wide scale in binding affinities from picomolar (pM) to millimolar (mM) raw values exhibit significant variance that could affect training stability.

Dataset composition

The chosen datasets vary in size, drug target pairs, and binding metrics, ensuring that the study covers a broad spectrum of drug-target binding prediction. The dataset characteristics are presented in Table 3.

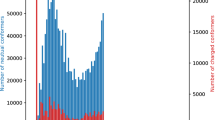

The DAVIS and KIBA datasets were used for training and testing in an 80:20 split, while the BindingDB dataset was employed exclusively for independent validation to assess the model’s ability to generalize to novel drug-target pairs can be observed in Fig. 2. To mitigate overfitting and ensure a clear evaluation of the model’s generalization capability, we deliberately limited the training and test datasets to subset samples. This controlled setting enables us to assess how well the model performs on unseen data. Datasets were selected because of their diversity, reliability, and relevance in drug discovery applications. These datasets are well-suited and standard for high-precision affinity models for DTI prediction. Exploratory data analysis has been done to reveal more molecular characterizations of the datasets.

Exploratory data analysis (EDA)

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) was conducted to understand the distribution and relationships among molecular descriptors, including molecular weight, lipophilicity (logP), hydrogen bond donors, and hydrogen bond acceptors, concerning binding affinity values.

Figures 3 and 4, and 5 show the scatterplots of these descriptors across the DAVIS, KIBA, and BindingDB datasets, showing their distributions and pairwise correlations with binding affinity. These visualizations focus on how physicochemical properties influence interaction strength across different datasets. The observed variability in binding affinity, spanning from nanomolar (nM) to millimolar (mM) concentrations, necessitated logarithmic transformation to normalize the values and reduce variance during model training. This transformation enhances numerical stability and facilitates regression modeling.

Statistical analysis of datasets

To further understand the dataset properties, the log-transformed binding affinity values were subjected to statistical analysis. Table 4 presents the mean, standard deviation, and skewness for every dataset. Observably, the KIBA dataset shows the smallest variance (σ = 0.031) and maximum skewness and has a more uniform and right-tailed affinity score distribution, which are reasons for its higher model stability and performance. Conversely, BindingDB has the largest variance (σ = 1.372), implying a broader range of molecular interactions and higher complexity. The DAVIS dataset, while smaller, exhibits moderate variability and positive skewness, reflecting a prevalence of strong interactions with occasional weak binders.

These results demonstrate the non-linear, complicated nature of molecular descriptors vs. binding affinity, lending validity to the implementation of quantum-improved kernel learning within the QKDTI approach. The mapping of molecular attributes to a Hilbert space within quantum can enhance the ability of the model to capture the complexities of such relationships, allowing for better generalization and prediction performance.

Data preprocessing

The preprocessing phase is the critical step in developing a model. In this phase, it guarantees that the training and testing of the proposed model can be performed efficiently.

This process involves several operations shown in Fig. 6 applied to the DAVIS, KIBA, and BindingDB datasets, which serve as validation sets and contain diverse DTI pairs with varying binding affinity measurements. Due to the imbalance and heterogeneity of these datasets, feature transformation and standardization techniques were employed to maintain consistency across inputs and optimize model performance. At the outset, each of these datasets got its respective binding values from all data retrieved with ranges from nanomolar (nM) to millimolar (mM) concentrations. To normalize a vast extent of range, majorly fluctuating binding values were logarithmically transformed as:

Where Y represented the original binding affinity value, and Ylog described the transformed value of Y. This transformed log ensures that extremely large values would not dictate the learning trend while also providing variance stabilization for their multipurpose conformity towards regression models. Subsequently, to the transformation, standardization of features was performed using Z-score normalization, which scales each feature by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation as derived from the following:

Where X is the original value of the feature, µ is the mean across all instances for that feature while, σ is the standard deviation. This step was crucial in ensuring that no single feature disproportionately influenced the model, particularly when integrating quantum feature mapping techniques. To address missing values, a dataset-specific approach was taken. If any binding affinity values were missing, the corresponding data entries were removed. For missing molecular descriptors, the mean of the respective feature was used for imputation. Additionally, protein sequence embeddings were recomputed where necessary, ensuring a complete dataset for training.

Given the high-dimensional nature of drug and protein representations, principal component analysis was applied to reduce dimensionality while preserving 95% of the variance, making subsequent quantum computations more efficient. Finally, preprocessed datasets were then converted into a precomputed kernel format, enabling efficient training of the QKDTI model. These preprocessing steps ensured that the DAVIS, KIBA, and BindingDB datasets were well-structured and computationally optimized, allowing for seamless integration into the hybrid quantum-classical learning pipeline. This preprocessing framework improves numerical stability and facilitates effective comparisons between quantum kernel learning and classical techniques in DTI prediction.

Model development

In the previous section, the preprocessing pipeline was described to convert unstructured drug-target data to be built into a feature space suitable for machine learning models. Techniques including log transformation, standardization, quantum feature mapping, nyström kernel approximation, and feature fusion were applied to optimize learning conditions and enhance the model. Following data preprocessing, model training is performed. This section focuses on training strategies, optimization, and evaluation of QSVR meant for predicting drug-target binding affinities. The next steps should include an evaluation and training phase for several methods. This work aims to determine if the quantum-enhanced model provides explicit benefits in terms of accuracy, generalization, and computational efficiency. Already having outlined the details of the process including training with the QKDTI model, there are differences in contrast to classical models which do not rely on any manually developed kernels-either linear, polynomial, or RBF. Rather, QKDTI uses quantum feature mapping to produce kernels that exploit quantum entanglement and superposition to allow for a richer representation of data.

Quantum feature mapping

Once preprocessing was complete, the data was organized for quantum feature mapping, where molecular features were encoded into a quantum Hilbert space via parameterized quantum circuits (PQC)34 can be observed in Fig. 7.

The quantum circuit used for QKDTI visualized in Fig. 8, consists of 𝑛 qubits corresponding to the molecular descriptor, which allows the embedding of high-dimensional molecular features into the quantum system. Each qubit is initialized in the standard basis state ∣0⟩. A Hadamard (𝐻) gate is applied on each of the qubits to attain the even distribution state, which allows for quantum parallelism:

This superposition allows the system to access multiple states of molecular features at once, boosting the model’s generalization capacity over different chemical structures. Once the Hadamard operation is performed, encoding of features is done using successive and parameterized rotation gates, namely the 𝑅𝑌 and 𝑅𝑍, which variably influence the qubit state from the descriptor value input given by the molecule. The transformation applied to each qubit is given by:

Here, \(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}\) denotes the 𝑖th feature for the input molecular vector. These gates guarantee that the quantum amplitudes represent the molecular descriptors in a high-dimensional feature space. Controlled-Z (𝐶𝑍) gates couple adjacent qubits to introduce a dependence and correlation of features. The 𝐶𝑍 gate is defined as:

Here, it introduces correlations among phases across neighboring qubits, with a corresponding interaction angle that incorporates molecular interactions, which cannot be done by classical feature representations. The entanglement thus created ensures the quantum feature encoding captures complicated relations among molecular descriptors, finally enhancing the expressiveness of the quantum feature map.

Once the quantum feature encoding is complete, the expectation values of the quantum states are measured to compute the quantum kernel, which serves as the core of the QSVR model. The quantum kernel function was then computed using:

Here, 𝜙(\(\:x\)) represents a quantum-encoded transformation of the input features. Due to the exponentially rising computation complexity of the quantum kernel matrix for large datasets, a batch-wise computation strategy was adopted, splitting pairs into batches of 50 samples to ensure training efficiency. Besides, nyström approximation was additionally used to better improve computation efficiency and scalability to approximate the quantum kernel matrix.

As shown in Fig. 9, the Nyström method permits approximation of large kernel matrices using a small set of landmark points, defined as follows:

Where \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{m},\text{m}\:}\), which contains a subset of the full kernel matrix computed using a limited number of samples, and \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{m},\text{n}}\) which gives the projection of the full dataset on these selected samples. By this approximation, the computational complexity is tremendously reduced, and at the same time, high accuracy concerning the actual kernel is retained.

Quantum optimization

Once the quantum kernel is calculated, it is used as an input to the QKDTI model and follows a standard epsilon-SVR optimization framework. The SVR objective function minimizes the following loss function.

Subject to the constraints.

w is the weight vector that the model learns. 𝜉𝑖 and 𝜉𝑖∗ allow small errors in predictions. 𝐶 controls the trade-off between accuracy and model complexity. 𝜖 sets the margin within which predictions are considered acceptable. This function helps QSVR find a balance between accuracy and generalization, preventing overfitting.

To train the QKDTI model effectively, we optimize various hyperparameters to achieve the best possible performance. The training process involves fine-tuning parameters that control the model’s complexity, computational efficiency, and generalization ability.

Hyperparameters

To optimize the performance of the QKDTI model, hyperparameters were carefully selected and tuned to ensure effective prediction.

Quantum circuit parameters

The quantum feature mapping in QKDTI utilizes eight qubits, each one representing a molecular descriptor. The qubits are put in a superposition state with Hadamard (𝐻) gates, then followed by parameterized rotation gates 𝑅𝑌(𝑥) and 𝑅𝑍(𝑥), which encode classical molecular feature values into quantum states. To introduce quantum entanglement and increase the correlation of the features, Controlled-Z (𝐶𝑍) gates were applied on pairs of adjacent qubits to exploit the complex interdependencies that can exist among molecular descriptors. The quantum circuit hyperparameters used in this study are represented in Table 5.

Quantum kernel approximation

To avoid kernel evaluations that would normally be found overpowering, the nyström approximation was adopted. This was achieved by picking out a batch of 50 to approximate the full kernel matrix, which would save on enormous costs while not significantly troubling the accuracy of the kernel. Furthermore, the double-batch computation considers 50 samples to be the batch during processing when ensuring extensive-scale kernel evaluation. The quantum kernels were fed to the SVR model when fitting it. SVR hyperparameters were thus jointly chosen for an optimal trade-off between model complexity and prediction accuracy. The hyperparameters related to the quantum kernel are outlined in Table 6.

Support vector regression (SVR) parameters

The regularization parameter (𝐶) was assigned a value of 1.0 to control the trade-off between efforts to minimize training error and maximize margin generalization. The epsilon (𝜖) parameter was set to 0.1, defining a tolerance range, with predictions inside that range being accepted as valid. The SVR model was fit using the Sequential Minimal Optimization (SMO) solver, which optimally solves the regression function. In the early stages of the modeling process, feature preprocessing is crucial to prepare input data for quantum embedding. In this study, PCA is used to reduce the dimensions of the features retained, accounting for 95% of the variance, so that only the most pertinent information is kept. In addition, Z-score normalization ensured that the molecular descriptors had a zero mean and unit variance before encoding them into quantum states. The SVR hyperparameters are provided in Table 7.

Optimal hyperparameter selection was essential for high predictive performance and low error rates. The Nyström approximation provided computational effectiveness without compromising the expressiveness of kernels. PCA-driven dimensionality reduction also enhanced generalization by reducing redundant molecular descriptors. Through the use of these optimizations, QKDTI showed substantial superiority over traditional models in binding affinity prediction on the DAVIS, KIBA, and BindingDB datasets.

Computational environment

The QKDTI model was implemented and tested using the following quantum-classical hybrid environment to ensure computational feasibility and performance evaluation.

Framework Used:

-

Quantum Machine Learning: PennyLane.

-

Quantum Backend: Qiskit for quantum kernel evaluations.

-

Classical ML Libraries: Scikit-learn, PyTorch, TensorFlow.

Hardware & Execution Environment:

-

Quantum Simulations: Conducted using PennyLane simulator.

-

GPU Acceleration: NVIDIA T4 GPU on Kaggle (cloud-based execution).

Experimental results and discussion

The experimental evaluation of the QKDTI model was conducted on three benchmark datasets: DAVIS, KIBA, and BindingDB, assessing its performance in predicting drug-target interaction binding affinity. The experiments aimed to compare the effectiveness of QKDTI against classical machine learning models, particularly standard SVR, in terms of prediction accuracy, generalization ability, and computational efficiency.

Performance metrics

Mean squared error

Mean Squared Error (MSE) is one of the most commonly used metrics for regression tasks. It quantifies the average squared difference between the actual binding affinity values and the model’s predictions:

Where:

-

\(\:{\text{Y}}_{\text{i}}\:\)represents the actual drug-target binding affinity.

-

\(\:{\widehat{\text{Y}}}_{\text{i}}\:\)is the predicted binding affinity from the QSVR model.

-

N is the total number of drug-target pairs. A lower MSE value indicates that the model’s predictions are closer to the actual binding affinity values, meaning better accuracy.

Root mean squared error (RMSE)

The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is another regression metric provides a more interpretable measure of prediction error by maintaining the same unit as target variable

A lower RMSE indicates that, smaller deviation to the actual values.

Prediction accuracy

While regression models do not have a traditional “accuracy” metric like classification models40, we define a prediction accuracy measure to assess how close the predicted values are to the actual values:

A higher accuracy percentage means that the model’s predictions closely match the real binding affinities.

R2 score

R² Score identifies the amount of dependent variable variation that independent variables can predict:

Where \(\:\widehat{Y}\:\)is the mean of actual values. The model’s fit strength increases when the value of R2 approaches 1, but decreases when it becomes negative.

Pearson correlation coefficient(r)

The actual and predicted value relationship gets measured through Pearson’s r. It is computed as:

The value scale extends from − 1 to 1 with 1 representing a perfect positive linear association between variables. Better predictive correlation exists when values rise.

Area under ROC curve

The AUC-ROC serves as a typical classification metric but for DTI regression by applying thresholding to affinity scores to determine model discrimination between strong and weak binders. The performance of a classification system becomes more accurate as the AUC value approaches 1 even when using threshold-based approximations.

Results and discussion

The experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the QKDTI prediction across three benchmark datasets: DAVIS, KIBA, and BindingDB can be observed in Table 8. To determine the efficacy of prediction, QKDTI was trained on the datasets, ensuring computational feasibility.

To evaluate the performance, the proposed method is compared with multiple classical and quantum models. The efficacy of QKDTI was evaluated using performance metrics predicting the binding affinity. This comparison includes three quantum models for evaluation: Quantum Neural Networks (QNN), Variational quantum circuit (VQC), Quantum Feature Fusion Regression (QFFR), and Quantum Transformers. The QNN model used quantum rotation encoding through RY and RZ gates along with Pauli-Z measurements to build its basic variational quantum circuit design. Strongly Entangling Layers added to the QFFR model allowed it to create complex quantum feature interactions, which captured molecular relationships at higher dimensions. Quantum Transformer utilized a multi-head attention mechanism and feed-forward networks to serve as the quantum model for the molecular descriptor relationship.

Comparative analysis

The performance of various classical and quantum machine learning models was evaluated across the three datasets. The results are summarized in the following figures, tables, and discussions.

Across all the datasets and models, QKDTI consistently outperformed classical and quantum models.

To evaluate the performance of QKDTI, we compared it against a curated set of classical and quantum models across the benchmark datasets: DAVIS, KIBA, and BindingDB. These models were selected based on the following rationale:

-

Models like SVR, Ridge Regression, and Random Forest are standard baselines in DTI tasks and have shown strong performance across multiple benchmark studies20,23,29.

-

Included a broad spectrum of model typeslinear, nonlinear, ensemble, and deep learning, as well as quantum models—to ensure comprehensive evaluation.

-

Quantum Neural Networks (QNN), Quantum Feature Fusion Regression (QFFR), Variational Quantum Circuits (VQC), and Quantum Transformers represent cutting-edge developments in quantum machine learning for molecular modeling and DTI prediction.

Performance evaluation was based on multiple metrics, including MSE, RMSE, R², AUC-ROC, Pearson correlation, and prediction accuracy to assess regression performance across classical and quantum paradigms. These models were used extensively to perform regression tasks in computational drug discovery because of their validation with benchmark DTI datasets. Performance comparison can occur among linear, non-linear, and ensemble-based machine learning paradigms, with a focus on MSE, RMSE, R2, AUC-ROC, Pearson and Accuracy.

The results from Figs. 10, 11 and 12 visualization analysis correlate with the interesting trend: Among classical machine-based learning models and quantum-enhanced models, notably QKDTI, work closer to physically realistic representations of molecular interactions, hence providing better binding affinity predictions. On the KIBA dataset, QKDTI achieved low MSE of 0.0003 and R2 of 0.6415 indicating strong prediction. QKDTI performed well with the DAVIS dataset also with the MSE of 0.25 and a pearson correlation of 0.921, confirming its generalizability. In the case of BindingDB, which is a raw dataset proposed model provided a lower RMSE of 0.9722 and a reasonable R2 0.521. Among the three databases considered in this work, KIBA yields the highest accuracies across all models, with QKDTI achieving as high as 99.99% in comparison to performances over DAVIS. This result has been achieved mainly due to the well-structured and canonical scoring system in KIBA, which assimilates several bioactivity estimations like Ki, Kd, IC50, and EC50 into a single KIBA score, all of which lower noise and variation for a more uniform and predictable dataset for machine learning algorithms. KIBA mainly consists of kinase inhibitors, a drug category with highly correlated molecular structures and interaction patterns, allowing the models to extract significantly more meaningful features. The higher signal-to-noise ratio and better feature consistency further enable quantum-enhanced models like QKDTI to achieve superior predictive accuracy by effectively mapping molecular interactions into quantum states. Moreover, KIBA ensures better generalization, unlike DAVIS and BindingDB, which contains higher variability in binding affinity scores. The consistency in prediction performance across the DAVIS, KIBA, and BindingDB datasets also shows the great potential of quantum-enhanced regression technologies to revolutionize computational drug discovery, opening a door to more accurate and scalable predictive modeling.

To assess the significance of the performance between different models the statistical analysis is performed. This study conducted paired t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests on the prediction outputs of all the datasets. The analysis can be observed in the Table 9.

To validate the performance gains of quantum models over classical approaches, statistical tests were conducted across the KIBA, DAVIS, and BindingDB datasets. The proposed QKDTI model consistently yielded statistically significant improvements, with p-values below 0.05 in both paired t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Notably, on the KIBA dataset, QKDTI achieved a t-statistic of 3.05 (p = 0.014) for MSE and 2.0 (p = 0.031) in the Wilcoxon test, while Quantum Transformer exhibited a strong correlation performance with a t-statistic of 4.05 (p = 0.004). Similar trends were observed on DAVIS and BindingDB, confirming that quantum models not only reduced prediction errors but also better captured drug-target interaction patterns. These statistically significant results underscore the robustness and reliability of quantum-enhanced models in DTI prediction tasks.

Discussion

This study introduces QKDTI, a novel framework, confirming its ability to enhance DTI prediction through quantum-enhanced learning techniques. The research objectives were systematically addressed:

-

QKDTI is a quantum-enhanced framework that integrates QSVR and quantum feature mapping to optimize molecular interaction predictions.

-

Performance comparisons demonstrated QKDTI’s superiority over classical ML models, showing higher accuracy and statistical significance was done using the paired t–tests and Wilcoxon confirming that the improvement was reasonable not by chance.

-

Quantum computing enabled QKDTI to handle biochemical data more effectively, improving binding affinity predictions and generalization across datasets.

-

While most of the studies in DTI used the classification techniques leading imbalance class distribution, this work used a continuous distribution by applying a log transformation to binding affinity scores, which minimizes the skewness. This helps to handle class imbalance and provides and good binding strength.

The findings provide strong evidence that quantum-enhanced models like QKDTI can revolutionize computational drug discovery, offering higher predictive reliability, computational efficiency, and improved scalability for high-throughput screening applications. This work relies on quantum simulation which is restricted by the number of qubits, short coherence time due to the deployment of real-time quantum devices. Quantum models possess complex structures that make it difficult to obtain easily interpretable biological information from their learned representations. The quantum models on working on experimental validation can be successful to drug discovery when performed on quantum hardware.

Conclusion and future work

This study proposed QKDTI - Quantum Kernel Drug-Target Interaction, a novel quantum-enhanced framework for drug-target interaction prediction. By combining quantum feature mapping with QSVR through the QKDTI model predict binding affinity more accurately and efficiently. The encoding process becomes easier through QKDTI because quantum kernel learning in the framework enables better model generalization across different datasets. The nyström approximation functions as a computational optimization tool by ensuring scalability and using fewer resources in comparison to traditional methods. QKDTI trains on DAVIS and KIBA datasets and then evaluates its predictions on the independent BindingDB, where the proposed model provides superior result compared to traditional machine learning models and other quantum regression models. The implemented results resulted in substantial progress through reduced errors together with higher predicted binding affinities. Data imbalance challenge was addressed by the model through log transformation and other strategies that enhanced its generalization and robustness performance. As part of the system integration with quantum computing principles, the developers created an advanced molecular interaction model that maintained accuracy levels with subset data.

In addition to its predictive advantages, QKDTI meets sustainability goals by integrating a lower computational burden into classical drug discovery. While classical in-silico approaches typically require high-computing platforms, which contribute to energy consumption and subsequently increase carbon footprints, the principles of quantum computing incorporated into QKDTI offer a green alternative that supports sustainability in pharmaceutical sciences. The model’s optimized computational framework solves the redundancy problem, making it a viable, sustainable option for large-scale biomedical applications that promote responsible and resource-efficient AI in drug discovery.

The future work shall additionally bear witness to widening the scope of biochemical datasets considered by QKDTI, further refinement of the hybrid quantum-classical architectures deployed, and achieving better interpretability of outputs to make them useful in clinical decision-making. QKDTI can be extended beyond protein target predictive capabilities to non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs, since these regulatory elements play an important role in disease progression39,41,44. The prediction of microRNA–small molecule interactions through QKDTI adaptation offers exciting research potential because recent investigations show RNA-targeted interactions have therapeutic value. The proposed model can be used for RNA sequence embeddings and structural descriptions because its quantum kernel framework works with different input modalities, making it suitable for tasks requiring minimal experimental data. Another scope includes refining the hybrid quantum-classical model to improve stability and convergence, especially as current quantum backends are constrained by limited qubit counts, noise, and decoherence that restrict model complexity and scalability. By propounding a scalable and sustainable quantum-driven approach, this research also paves the way for the next generation of computational drug discovery by providing a green path toward energy-efficient and high-accuracy molecular interaction predictions that support global health objectives through its contribution to United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3: Good Health and Well-Being.

Data availability

The dataset used in this proposed research is available in open access. The codes for implementation and numerical analysis used in this work will be made available online in GitHub resources for the research community to explore based on the request to the corresponding author.

References

Núñez, S., Venhorst, J. & Kruse, C. G. Target-drug interactions: first principles and their application to drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 17 (1–2), 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DRUDIS.2011.06.013 (2012).

Pliakos, K. & Vens, C. Drug-target interaction prediction with tree-ensemble learning and output space reconstruction. BMC Bioinform. 21, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-020-3379-z (2020).

Chen, R., Liu, X., Jin, S., Lin, J. & Liu, J. Machine learning for Drug-Target interaction prediction. Molecules 23 (9), 2208. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23092208 (2018).

Abdel-Basset, M., Hawash, H., Elhoseny, M., Chakrabortty, R. K. & Ryan, M. DeepH-DTA: deep learning for predicting drug-target interactions: a case study of COVID-19 drug repurposing. Ieee Access. 8, 170433–170451 (2020).

Smaldone, A. M. & Batista, V. S. Quantum-to-Classical neural network transfer learning applied to drug toxicity prediction. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20 (11), 4901–4908. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.4c00432 (2024). Epub 2024 May 25. PMID: 38795030.

Sathan, D. & Baichoo, S. Drug Target Interaction prediction using Variational Quantum classifier, 2024 International Conference on Next Generation Computing Applications (NextComp), Mauritius, 2024, pp. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/NextComp63004.2024.10779674

Thafar, M. A. et al. DTiGEMS+: drug-target interaction prediction using graph embedding, graph mining, and similarity-based techniques. J. Cheminform. 12, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-020-00447-2 (2020).

Barkat, M., Moussa, S. & Badr, N. Drug-target interaction prediction using machine learning. 480–485. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICIS52592.2021.9694127

Ahn, S., Lee, S. & Kim, M. Random-forest model for drug–target interaction prediction via Kullback–Leibler divergence. J. Cheminform. 14, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-022-00644-1 (2022).

Guvenilir, H. A. & Doğan, T. How to approach machine learning-based prediction of drug/compound–target interactions. J. Cheminform. 15 (16). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-023-00689-w (2023).

Wen, M. et al. Deep-learning-based drug-target interaction prediction. J. Proteome Res. 16 (4), 1401–1409. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00618 (2017).

Wang, Y. B. et al. A deep learning-based method for drug-target interaction prediction based on long short-term memory neural networks. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 20 (Supp6 2), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-1052-0 (2020).

You, J., McLeod, R. D. & Hu, P. Predicting drug-target interaction network using deep learning model. Comput. Biol. Chem. 80, 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2019.03.016 (2019).

Huang, K. et al. DeepPurpose: A deep learning library for drug–target interaction prediction. Bioinformatics 36 (22–23), 5545–5547. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1005 (2020).

Feng, Q., Dueva, E., Cherkasov, A. & Ester, M. (2018) PADME: A deep learning-based framework for drug-target interaction prediction. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1807.09741 (2018).

Sun, Y., Li, Y. Y. & Leung, C. K. March, Pingzhao Hu, iNGNN-DTI: prediction of drug-target interaction with interpretable nested graph neural network and pretrained molecule models, bioinformatics, 40, issue 3, btae135, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btae135

Bai, P. et al. Interpretable bilinear attention network with domain adaptation improves drug–target prediction. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00605-1 (2023).

Wei, J. et al. Efficient deep model ensemble framework for Drug-Target interaction prediction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15 (30), 7681–7693. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.4c01509 (2024). Epub 2024 Jul 22. PMID: 39038219.

Zhou, Z. et al. Revisiting drug-protein interaction prediction: a novel global-local perspective. Bioinformatics 40 (5), btae271. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btae271 (2024). PMID: 38648052; PMCID: PMC11087820 and 36411674.

Zhang, L., Wang, C. C. & Chen, X. Predicting drug-target binding affinity through molecule representation block based on multi-head attention and skip connection. Brief Bioinform. ;23(6):bbac468. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac468. PMID: 36411674.

Bikku, T. et al. Improved quantum algorithm: A crucial stepping stone in quantum-powered drug discovery. J. Electron. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-024-11275-7 (2024).

Domingo, Laia & Chehimi, M. & Banerjee, S. & Yuxun, S. & Konakanchi, Sandeep & Ogunfowora,L. & Roy, Shaswata & Selvarajan, S. & Djukic, M. & Johnson, C. (2024). A Hybrid Quantum-classical Fusion Neural Network to Improve Protein-ligand Binding Affinity Predictions for Drug Discovery. 126–131. 10.1109/QCE60285.2024.10265.

Rayhan, F. et al. iDTI-ESBoost: identification of drug target interaction using evolutionary and structural features with boosting. Sci. Rep. 7, 17731. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18025-2 (2017).

Li, N., Yang, Z., Wang, J. & Lin, H. Drug–target interaction prediction using knowledge graph embedding. iScience 27 (6), 109393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.109393 (2024).

Quan, N. et al. MFCADTI: improving drug-target interaction prediction by integrating multiple features through a cross-attention mechanism. BMC Bioinform. 26, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-025-06075-7 (2025).

El-Behery, H. et al. An ensemble-based drug-target interaction prediction approach using multiple feature information with data balancing. J. Biol. Eng. 16, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13036-022-00296-7 (2022).

Abbasi Mesrabadi, H., Faez, K. & Pirgazi, J. Drug–target interaction prediction based on protein features, using wrapper feature selection. Sci. Rep. 13, 3594. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30026-y (2023).

Nguyen, T., Le, H., Quinn, T. P., Nguyen, T. & Le, T. D. Svetha venkatesh, graphdta: predicting drug-target binding affinity with graph neural networks, bioinformatics, 37, issue 8, March 2021, Pages 1140–1147, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa921

Huang, K., Xiao, C., Glass, L., Sun, J. & & & MolTrans: molecular interaction transformer for drug–target interaction prediction. Bioinformatics 37 https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa880 (2020).

Long, S., Zhou, Y., Dai, X. & Zhou, H. Zero-shot 3d drug design by sketching and generating. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 23894–23907 (2022).

Yasunaga, M. et al. Deep bidirectional language-knowledge graph pretraining. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 37309–37323 (2022).

Isert, C. et al. QMugs, quantum mechanical properties of drug-like molecules. Sci. Data. 9, 273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01390-7 (2022).

Gircha, A. I. et al. Hybrid quantum-classical machine learning for generative chemistry and drug design. Sci. Rep. 13, 8250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32703-4 (2023).

Torabian, E. & Krems, R. Molecular representations of quantum circuits for quantum machine learning. (2025). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.05955

Liu, L., Wei, Y., Zhang, Q. & Zhao, Q. SSCRB: Predicting circRNA-RBP Interaction Sites Using a Sequence and Structural Feature-Based Attention Model. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. ;28(3):1762–1772. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2024.3354121. Epub 2024 Mar 6. PMID: 38224504 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Multi-task aquatic toxicity prediction model based on multi-level features fusion. J. Adv. Res. 68, 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.06.002 (2025). Epub 2024 Jun 4. PMID: 38844122; PMCID: PMC11785906.

Yin, S. et al. Predicting the potential associations between circrna and drug sensitivity using a multisource feature-based approach. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 28 (19), e18591. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.18591 (2024). PMID: 39347936; PMCID: PMC11441279.

Wang, J. et al. Predicting drug-induced liver injury using graph attention mechanism and molecular fingerprints. Methods 221, 18–26 (2024). Epub 2023 Nov 30. PMID: 38040204.

Chen, Z. et al. DCAMCP: A deep learning model based on capsule network and attention mechanism for molecular carcinogenicity prediction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 27 (20), 3117–3126. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.17889 (2023). Epub 2023 Jul 31. PMID: 37525507; PMCID: PMC10568665.

Wang, W., Zhang, L., Sun, J., Zhao, Q. & Shuai, J. Predicting the potential human lncRNA-miRNA interactions based on graph convolution network with conditional random field. Brief Bioinform. ;23(6):bbac463. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac463. PMID: 36305458.

Mukesh, K., Jayaprakash, S. & Rangarajan, P. K. QViLa: Quantum Infused Vision-Language Model for Enhanced Multimodal Understanding. SN Computer Science. 5. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-024-03398-9

Saggi, M. K., Bhatia, A. S. & Sabre Kais. Federated quantum machine learning for drug discovery and healthcare. 269–322. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.arcc.2024.10.007

Bhatia, A. S., Saggi, M. K. & Kais, S. Quantum machine learning predicting ADME-Tox properties in drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63 (21), 6476–6486 (2023).

Yang, X. et al. A Multi-Task Self-Supervised strategy for predicting molecular properties and FGFR1 inhibitors. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 12 (13), e2412987. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202412987 (2025). Epub 2025 Feb 8. PMID: 39921455; PMCID: PMC11967764.

Wang, T., Sun, J. & Zhao, Q. Investigating cardiotoxicity related with hERG channel blockers using molecular fingerprints and graph attention mechanism. Comput. Biol. Med. 153, 106464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106464 (2023). Epub 2022 Dec 20. PMID: 36584603.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. conceptualized the study and designed the methodology. G.P. implemented the Quantum Kernel Drug-Target Interaction (QKDTI) framework and performed the experiments. R.P.K. supervised the research and provided critical revisions. G.P. and A.A. wrote the main manuscript text. R.P.K. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pallavi, G., Altalbe, A. & Kumar, R.P. QKDTI A quantum kernel based machine learning model for drug target interaction prediction. Sci Rep 15, 27103 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07303-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07303-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Quantum-machine-assisted drug discovery

npj Drug Discovery (2026)