Abstract

Chemotherapy can cause several long-term side effects that can affect cancer survivors’ quality of life-, notably cognitive decline in response to select chemotherapeutic agents. Studies using both human patients and animal models have been employed to determine the regions of the brain that are subject to the most considerable changes, furthermore, elucidating possible molecular mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment (CICI). However, the reason behind the differences in symptoms and duration of CICI between patients have yet to be identified. This study focused on understanding whether the systemic delivery of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC chemotherapeutics) causes any epigenetic factors to change in the female rat prefrontal cortex (PFC), possibly providing an insight into the variability of clinical manifestations of CICI. We evaluated DNA methylation levels and patterns in the PFC after AC-chemotherapy administration. We also demonstrated changes in histone deacetylase and acetyl transferase activity levels in the murine PFC in response to treatment. Despite no change in the global DNA methylation level, we found that several genes related to neuronal development and maintenance were differentially methylated in the promoter and exon regions in the rat PFC. Our study showed a significant increase in the expression of the de novo DNA methyl transferase DNMT3a compared to the control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) toxicity is one of the prominent side effects of systemic delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs. This toxicity can lead to chemotherapy induced cognitive impairments (CICI) including deficiency in working memory, processing speed, attention span, executive function, and decision-making capability1,2,3. Though CICI symptoms may vary between cancer patients, recent clinical data have shown that the overwhelming majority of breast cancer survivors undergoing treatment experience some form of CICI. The notable impairment may occur during chemotherapy administration and persist for six months up to ten years after completion regimen1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10.

Clinical and pre-clinical studies have shown that chemotherapy mostly affects the cognitive functions like formation spatial memory, long-term memory, executive decision making etc. These cognitive functions are controlled by the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the mammalian brain11,12. Several molecular mechanisms impairing these regions have been established for different chemotherapy regimens using animal and human models. Chemotherapy can induce apoptosis in neurons and suppress neurogenesis, specifically in the hippocampus13.Some prominent molecular mechanisms causing CICI include neuroinflammation14the activation of stress response pathways (ERK/AKT pathway)15the induction of oxidative stress in the CNS16and the activation of disease-associated microglia (DAMs).

Decades of research have enhanced the knowledge of molecular mechanisms of CICI. However, it is still unclear as to why there is such variation in neurological symptoms, severity, and duration in individuals receiving the same chemotherapy regimen. This discordance in symptoms indicates epigenetic changes beyond genetic and biochemical signaling. Epigenetics has long been established as an important regulator of brain development, neuron proliferation and differentiation, as well as formation of long-term memory. Epigenetic factors are also implicated in brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases. There have been few studies that have investigated the relationship between epigenetic factors and CICI demonstrating the involvement of histone modification17 and changes in gene expression profiles18 in murine brains using different chemotherapeutic agents.

Previously, our lab has used a cocktail of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC chemotherapy) in a tumor-free Sprague-Dawley female rat model to investigate behavioral and molecular changes involved in CICI15. These studies demonstrated that AC chemotherapy induces oxidative stress in the hippocampus of ovariectomized rats16. Additionally we demonstrated that AC-chemotherapy could impair cognitive functions of the rats in the same fashion independent of their hormonal status (intact or overectomized)15. Our previous studies were mainly focused on hippocampus but in this current study, we focus on another part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex (PFC), which is significantly involved in cognitive function. Our main goal was to identify possible epigenetic changes in PFC in response to AC chemotherapy, specifically the alterations in DNA methylation and histone acetylation.

To provide a clear structure of our study, we first investigated global methylation and hydroxymethylation level in PFC to establish a baseline. To support our global methylation and hydroxy methylation data we assessed differential changes in the mRNA expression level of key enzymes of DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation (DNMT1, DNMT3a, TET1, MeCP2). Next we investigated specific changes in DNA methylation level and which functional regions are most affected using whole genome bisufite sequencing (WGBS). We then assessed differential histone modification, particularly acetylation and deacetylation activity and some key enzmes involved in this process (CBP and CREB). The results from these experiments have identified potential epigentic mechamisms involved in AC chemotherapy treated rat PFC.

Results

Change in global DNA methylation and hydroxy-methylation level in the PFC after AC-chemotherapy exposure

We investigated PFC tissue lysate from animals treated with either with saline (control) or AC chemotherapy (experimental). Of note, a comparative analysis of total 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) frequency in both CpG and non CpG sites yielded no significant change in the global DNA methylation levels of mice that underwent chemotherapeutic conditioning (Fig. 1a). In contrast, we observed a 1.4 fold decrease of global DNA hydroxy methylation level (total 5-hmC) in the experimental group compared to the control (p-value: 0.050, Fig. 1e).

Changes in the global DNA methylation, hydroxy methylation level and gene expression level of essential enzymes involved following AC chemotherapy exposure in female rat PFC. (a) Bar graph representation of global DNA methylation level (5-mCytosine quantitation in both CpG and non-CpG sites) changes between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissue (p-value: 0.2778). (b) Bar graph representing changes in the DNMT1 gene expression level between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal PFC tissue (p-value: 0.3413). (c) Bar graph representation of the changes in the DNMT3a gene expression level between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissues (p-value: 0.0016). (d) Bar graph representation of the changes in the MeCP2 gene expression level after AC -chemotherapy treatment in animal tissues (p-value: 0.0286). (e) Bar graph representation of global DNA hydroxy-methylation level changes between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissue (p-value: 0.05). (f) Bar graph representation of the TET1 gene expression level changes between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissue (p-value: 0.0357). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. All of these experiments used four saline-treated animal samples and five chemotherapy-treated animal samples.

Change in expression level of DNMT1, DNMT3a, MeCP2, TET1 in the PFC following AC-chemotherapy exposure

Two prominent epigenetic markers, DNA methylation enzymes DNMT1 and DNMT3a were analyzed for gene expression analysis. This analysis revealed an approximate 2.1-fold decrease in the DNMT1 expression level (p-value: 0.3413) (Fig. 1b) in AC-chemotherapy treated animals. In contrast, the DNMT3a expression level increased approximately 60-fold post AC-chemotherapy treatment (p-value: 0.0016) (Fig. 1c). Evaluation of the gene expression of MeCP2, which is also involved in the DNA methylation process, showed an approximate 8-fold decrease following AC-chemotherapy treatment (p-value: 0.0286) (Fig. 1d).

We also evaluated the gene expression level of TET1, an enzyme involved in the DNA hydroxy-methylation process. Our data showed an increase of approximately 3.4 fold in AC-chemotherapy-treated animals compared to the control animals (p-value of 0.0357) (Fig. 1f).

Change in DNA methylation profile in the PFC following AC-chemotherapy exposure

To further investigate the aberrant changes in the DNA methylation pattern following AC-chemotherapy treatment, we performed whole genome bisulfite sequencing of the PFC DNA. Bisulfite sequencing detected methylation in CG, CHH, and CHG sites, where CHG and CHH represent non-CG methylation sites (H = A, T, C). In non-CG methylation, CHG referring to methylation of cytosines in the context of a G base, and CHH representing methylation in the context of A, T, or C. While we observed methylation in both CG and non-CG contexts, the percentage analysis of methylation across these sites revealed no significant differences between the chemotherapy and saline-treated animals (Fig. 2a-b). The methylation density analysis (Fig. 2c) indicated similar distributions of methylation across genomic contexts in both groups, suggesting that chemotherapy did not significantly alter the overall methylation patterns in the PFC.

Cytosine methylation density analysis in the different methylation sites, including CG, CHG, and CHH in the PFC after AC-Chemotherapy Exposure. (a) Pie chart representation of relative percentages of methylation at different cytosine sites (CG, CHG, and CHH) in the control (saline-treated) sample. (b) Pie chart representation of relative percentages of methylation at different cytosine sites (CG, CHG, and CHH) in chemotherapy-treated sample. (c) Violin plot representation of methylation density distribution across the whole genome. The x-axis represents sample type, with the red plot depicting the control (saline) group and the blue plot depicting the chemotherapy-treated group. The y-axis represents the percentage methylation density per 10 kb bin. The width of each violin plot reflects the number of bins in this methylation density distribution.

We investigated the changes in methylation level in genomic regions, upstream/downstream and genebody (Fig. 3a). Our analysis revealed treated PFC had overall higher methylation level in both CG and non-CG sites compared to control. Upstream/downstream regions are more differentially methylated than genebody. To better understand the functional implications of these differential methylation patterns observed in the genomic regions (Fig. 3a), we next investigated the methylation levels in specific functional genomic regions, including promoters, exons, introns, UTRs, CpG islands (CGI), CGI shores, and repeats (Fig. 3b). This data indicated a significant increase in the methylation levels in all three cytosine methylation sites, in the promoter, exon and UTR regions of the experimental (genome compared to the control animals). This data also showed higher methylation level differences in CHG and CHH sites than in the CG sites.

An overview of methylation level distribution in genomic regionsin CG, CHH, and CHG in the PFC for both control and AC-chemotherapy-treated animals. (a) The x-axis is genebody and up/dowmstream region, The y-axis is the methylation level. Two Y- axis labels are used in this plot: the left axis is the methylation level in the CHG and CHH sites, and the right axis shows the methylation level in the CG sites. Each region is divided into 50 bins and methylation level is calculate in each bin. TSS (transcription start site), TES (Transcription end site). (b) The x-axis is the functional genomic elements. The y-axis is the methylation level. Two Y- axis labels are used in this plot: the left axis is the methylation level in the CHG and CHH sites, and the right axis shows the methylation level in the CG sites. Each functional region is divided into 20 bins and each bin’s methylation level is calculated.

Analyzing the genes separately indicated the presence of both hypomethylated and hypermethylated genes after AC-chemotherapy treatment. We identified several genes that are known to be directly involved in neuron development and maintenance and are affected by ACs. Figure 4a shows a bar graph representing the hypermethylated and hypomethylated genes in the CG site compared to the control sample. Figure 4b shows a bar graph illustrating the hypermethylated and hypomethylated genes in the CHG context compared to the control sample. Finally, Fig. 4c shows a bar graph representing the hypermethylated and hypomethylated genes in the CHH context compared to the control sample. In these graphs, the x-axis represents the gene’s name, and the y-axis represents the methylation level of the gene. For example, sox 9, a gene involved in glial cell fate determination, is hypermethylated in its promoter region. In supplementary Table 1, we have included a list of differentially methylated genes that are involved in the neuron and nervous system development as well as maintenance.

Whole genome bisulfite sequencing data and the global DNA methylation data indicated that even though no significant changes were observed in the global DNA methylation levels followed by chemotherapy treatment, AC-chemotherapy exposure contributed to the emergence of a new DNA methylation pattern in the chemotherapy-treated animals. Changes in DNA methylation patterns in functional genomic regions like the promoters or the exons can contribute to changes in the gene expression profile in the PFC following AC chemotherapy treatment.

In the WBGS, we found a multitude of changes in the DNA methylation pattern with some of those genes involved in the development and maintenance of the CNS. We investigated the expression levels of a subset of the genes listed in supplementary Tables 1 to observe if their methylation status matches with their mRNA expression level. As these genes are methylated in different functional regions, we wanted to understand how their new methylation pattern altered their expression at the mRNA level. Therefore, we assessed the expression level of Wnt3, 2’,3’-cyclic nucleotide 3’ phosphodiesterase (CNP), and Myelin-associated glycoprotein (Mag).

WBGS showed that Wnt3 is hypermethylated in the exon region. The gene expression level of this gene decreased by approximately 2.5-fold in the AC-chemotherapy-treated animals compared to the saline-treated animals (p-value: 0.0357) (Fig. 4d), supporting our WGBS data. This experiment used four saline-treated animal samples and five chemotherapy-treated animal samples.

WBGS data of the other two genes, CNP and Mag, showed hypermethylation in the exon region of the genes. In addition, the CNP gene expression level analysis revealed a statistically significant approximate 60-fold decrease in gene expression level in treated animals compared to the saline-treated control animals (p-value: 0.0040) (Fig. 4e).

Interestingly, despite being potentially hypermethylated in the AC-chemotherapy-treated animals, the gene expression level of Mag increased by 15-fold in the treated animals compared to the saline-treated animals (p-value: 0.0317) (Fig. 4f). Even though bisulfite sequencing data showed hypermethylation in the exon region, the Mag gene expression was increased. This indicates that the hypermethylation in this gene did not affect its expression level.

Representation of the genes critical for brain development and functions and their differential methylation levels in CG, CHG, and CHH sites in the PFC after AC chemotherapy exposure. The x-axis represents genes showing levels in comparison with control after chemotherapy, and the y-axis represents the gene names. (a) Bar graph representation of hypermethylated and hypomethylated genes in chemotherapy-treated tissue at CG sites. (b) Bar graph representation of hypermethylated and hypomethylated genes in chemotherapy-treated tissue at CHG sites. (c) Bar graph representation of hypermethylated and hypomethylated genes in chemotherapy-treated tissue at CHH sites. (d) Bar graph representing changes in the Wnt3 gene expression level between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissue (p-value: 0.0357). (e) Bar graph representation of the CNP gene expression level change between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissue (p-value: 0.0040). (f) Bar graph representation of the changes in the MAG gene expression level between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissue (p-value: 0.0317). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. This experiment used four saline-treated animal samples and five chemotherapy-treated animal samples.

Change in histone acetytransferase (HAT) and deacetylase (HDAC) activity in the PFC after exposure to AC-chemotherapeutics

Analysis of HAT activity revealed no significant change in the PFC of AC-chemotherapy treated animals (Fig. 5a). These data indicate less involvement of histone acetylation in gene activation after chemotherapy treatment.

We also analyzed the gene expression level of the histone acetyl transferase enzyme, CBP (CREB Binding Protein), and its corresponding transcription factor CREB (cAMP Response Element-Binding protein). Our data showed no statistically significant changes in the CBP gene expression level, (p-value: 0.2063) (Fig. 5c). Interestingly, we observed an approximate 1.5-fold increase in CREB gene expression level in the experimental group, (p-value: 0.0286) (Fig. 5d).

In contrast to the histone acetyl transferase activity, we observed an approximate 2.5-fold increase in the histone deacetylation (HDAC) activity in the PFC of AC-chemotherapy exposed animals (p-value of 0.0143) (Fig. 5b). These data indicated potential gene suppression through histone modification after chemotherapy treatment.

Changes in histone acetyl transferase and histone deacetylase activity following AC chemotherapy regimen in female rat PFC. (a) The bar graph represents the HAT activity level change between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissue (p-value: 0.31). (b) A bar graph representation of the HDAC activity level change between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissue (p-value: 0.0143). (c) Bar graph representing changes in the CBP gene expression level between saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissues (p-value: 0.2063). (d) Bar graph representation of the change in CREB gene expression level between saline treated and chemotherapy-treated animal tissue (p-value: 0.0286). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. This experiment used four saline-treated animal samples and five chemotherapy-treated animal samples.

Discussion

In the past, our lab had established that AC-chemotherapy administration can cause decline in spatial memory in both ovariectomized and intact female Sprague-Dawley rats using behavioral assays15. We have also shown that it activates stress response pathway in female rat brain irrespective of their hormonal staus. Another study by our lab showed induction of neuroinflammation and oxidative damage following AC chemotherapy administration in the hippocampus of ovariectomized Sprague-Dawley rats16.

In this study, we investigated potential changes in the epigenetic regulators, DNA methylation, and histone acetylation following systemic administration of the AC-chemotherapy treatment in the PFC of the chemotherapy treated rat brain. Our findings suggest that AC-chemotherapy treatment can potentially alter DNA methylation patterns and histone deacetylase activity in the PFC of female rats.

Epigenetic regulation of cognitive decline following chemotherapy treatment has been investigated for the past few years. Research on histone modification and DNA methylation and their effect on gene expression profiles in different chemotherapy regimens has been explored. Previously, it was demonstrated that inhibition of HDAC6 can ameliorate the symptoms of CICI after doxorubicin treatment in a murine model19. Another study showed that mitomycin C treatment caused a decline in global DNA methylation levels and increase global hydroxy methylation level in female murine brain PFC18. However, the same study also reported that cyclophosphamide treatment did not induce significant changes in either global DNA methylation or hydroxymethylation levels. These findings suggest that different chemotherapy agents may induce distinct epigenetic changes, which highlights the need for further investigation into the effects of AC-chemotherapy in the PFC of female rats.

Our study extends this work by highlighting significant non-CG methylation changes, which are critical for gene expression regulation in the brain. This observation, in combination with our findings on histone deacetylase activity, suggests that AC-chemotherapy affects multiple layers of epigenetic regulation. These differences between our study and previous research may reflect the specific chemotherapy regimens used, as well as species-specific and model-specific factors.

We have demonstrated that even though there are no significant changes in the global DNA methylation level (Fig. 1a), there is an approximate 1.4-fold decrease in the global DNA hydroxy-methylation level (Fig. 1e) in the PFC. Additionally, our research showed a significant increase in gene expression levels of DNMT3a (Fig. 1c), a de novo DNA methyltransferase enzyme20 additionally increase (not statistically significant) in the gene expression levels of DNMT1 (1b), an enzyme involved in the maintenance of the inherited DNA methyl patterns in daughter cells20,21. Simultaneously, we demonstrated a significant increase in the gene expression level of TET1, an enzyme involved in DNA demethylation (Fig. 1f) in the PFC. Cytosine hydroxy-methylation is the first step of the DNA demethylation process22. Additionally, cytosine hydroxy-methylation can act as a robust epigenetic code and a gene repressor like cytosine methylation23. Previous studies have shown hydroxy-methylated cytosines are abundantly available in the mammalian brain24. Therefore, the decrease in hydroxy-methylation can indicate the involvement of DNA demethylation processes. This dataset indicates a dynamic process of DNA methylation and demethylation in the PFC genome following AC-chemotherapy administration.

Additionally, a significant decrease in the gene expression level of MeCP2 (Fig. 1d), a methyl-binding protein that represses transcription of genes with methylated promoter repression after DNA methylation25,26 was observed. MeCP2 has also been implicated in the upregulating expression of some genes27,28. DNMT3a and MeCP2 are highly expressed in neurons and involved in brain plasticity. Rajavelu et al. showed that MeCP2 regulates DNMT3a expression and activity to protect the genome from aberrant DNA methylation27. Therefore, the decreased expression of MeCP2 may be aiding the increased expression of DNMT3a and new methylation sites in the PFC genome.

On the other hand, the gene expression level analysis of TET1, the enzyme involved in converting 5’-mC to 5’-hmC, showed a significant increase in gene expression level in chemotherapy-treated animals. This result indicates that increased TET1 expression level reflects increased hydroxy-methylation of the cytosine followed by demethylation causing hypomethylation in some genes of the chemotherapy-treated animals. Additionally, past studies have implicated that overexpression of TET1 disrupts memory formation independent of its catalytic activity29. So, its increased expression level can also indicate a more direct role of TET1 in cognitive impairment. Therefore, it is crucial to identify the specific role of TET1 in CICI.

Kovulchak et al. had shown before treatment with cyclophomide alone can change global DNA methylation and hydroxy-methylation Whole genome bisulfite sequencing showed no overall difference in methylation level following AC-chemotherapy treatment, which supports our global methylation assay result (Fig. 2a-c). The bisulfite sequencing data also showed that different functional genomic areas were more methylated in chemotherapy-treated animals than in the control animals. Among all the functional genomic sites, promoter and exon regions were more methylated in the chemotherapy-treated animals (Fig. 3). Our data also showed that non-CG sites (CHH and CHG) were more methylated in the chemotherapy-treated animals compared to the saline-treated animals (Fig. 3a). These non-CG methylation sites are especially important in the regulation of gene expression and are often observed in certain animal tissues. The unique characteristics of the brain methylome can explain our data. Studies have shown that the mammalian brain has abundant non-CG methylation sites, CHH and CHG. CH methylation primarily occurs as a de novo methylation30. CH methylation is established and maintained by DNMT3a in post-natal neurons30. This result explains the increased DNMT3a gene expression levels in the treated animal tissues.

Bisulfite sequencing analysis also revealed several genes in the chemotherapy-treated animals were differentially methylated (either hyper- or hypo-methylated) from the saline-treated animals (Fig. 4a-c). The increased gene expression levels of DNMT3a and TET1 also support this data. This indicates a synchronized activity of DNA methylation and hydroxy-methylation that can create a new methylation pattern in chemotherapy-treated animals. From the differentially methylated gene list, we identified several genes that have critical implications for the development and function of neurons (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, to understand whether the gene expression level is regulated according to the new DNA methylation pattern in the chemotherapy-treated animals, we did a preliminary study of some of the genes listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Wnt3 is involved in synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis31. In the bisulfite sequencing data, the Wnt3 exon is hypomethylated in the chemotherapy-treated animal. We expected an increased gene expression due to hypomethylation of the gene. Still, we observed a significant decrease in the gene expression level in the chemotherapy-treated animals (Fig. 4d). This data indicates that apart from DNA methylation, Wnt3 expression could be regulated by other factors, such as the expression of retinoic acid binding protein (RBP). Wnt3 transcription is regulated by the transcription factor retinoic acid (RA). Our WBGS data also indicated hypermethylation of the RBP, which helps in RA migration. Therefore, decreased expression of RBP could lead to decreased expression of Wnt3. It should be noted that a decrease in Wnt3 expression also supports the decreased neurogenesis in CICI32.

Apart from Wnt3, we also analyzed the gene expression levels of CNP, which significantly protects rat brain mitochondria33,34. In the bisulfite sequencing data, CNP was hypermethylated in the exon region. Analysis of CNP expression level showed a significant reduction in gene expression in chemotherapy-treated animals compared to the saline-treated animals (Fig. 4e), supporting the bisulfite sequencing data.

Previously, our lab reported an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the hippocampus after doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide treatments in rats16. Therefore, there is a possibility that a chemotherapy-induced decrease in CNP expression in the PFC makes neuronal mitochondria more vulnerable and creates more ROS. This phenomenon will ultimately lead to neuronal cell death. However, analysis of another hypermethylated gene in the exon region, Mag, showed a significant increase in expression in chemotherapy-treated animals. This gene increases axon-myelin and -cytoskeleton stability35. The increased gene expression level of Mag (Fig. 4f) can be due to the location of hypermethylated exon or due to another epigenetic regulator. These results indicate that gene expression in the PFC of chemotherapy-treated animals is potentially regulated by other factors apart from DNA methylation. We are currently investigating the expression levels of other genes we have given in supplementary Table 1.

We explored the scope of histone acetyl transferase and deacetylation activity in the CICI. Analysis of the HAT activity revealed no significant change between the chemotherapy-treated and saline-treated animals (Fig. 5a). Additionally, analysis of the gene expression level of histone acetyl transferase enzyme, CBP (Fig. 5c), indicated no significant change between the chemotherapy-treated and saline-treated animals. We selected CBP as a HAT enzyme as previous studies have shown its role in central nervous system development and neurological disorders36. This data set showed that the AC-chemotherapy treatment does not affect the histone acetyl transferase enzyme, CBP, or its activity. CBP acts as a co-activator of CREB protein, a transcription factor37,38. CREB/CBP complex induces transcription activation37. Analysis of CREB gene expression level showed a significant increase in its mRNA level in the chemotherapy-treated animals compared to the saline-treated animals (Fig. 5d). Past studies have also demonstrated that CREB can be activated by phosphoserine-133-independent mechanisms instead of CBP37. Our result indicates that CREB may be potentially stimulated by other mechanisms rather than binding to CBP for transcription activation in the chemotherapy-treated animals. It should also be noted that an increased mRNA level of CREB does not indicate the presence of functional protein. Therefore, our investigation of the activity of CREB in the PFC of AC-chemotherapy-treated animals is essential.

Further histone de ase (HDAC) activity analysis showed that HDAC activity increased significantly in the chemotherapy-treated animals (Fig. 5b). Past studies have shown that cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil cocktail treatment decreases HDAC activity in the hippocampus17. Conversely, we found that doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide cocktail treatment increase histone deacetylation activity in the PFC.

Our study suggests that AC-chemotherapy affects multiple layers of epigenetic regulation in the PFC, contributing to changes in gene expression that may drive CICI. DNA methylation, hydroxy-methylation, and histone deacetylation work together to create a new gene expression profile in chemotherapy-treated animals. Future studies, including acetylome profiling, will provide a more detailed understanding of epigenetic regulation in the PFC of chemotherapy-treated animals.

This study provides further insight into the modulations in the DNA methylation pattern and histone acetyl transferase and deacetylase activity in the PFC of female rat brains following AC-chemotherapy administration. Further studies are needed to elucidate how DNA methylation and histone modification work together to cause cognitive impairment. CICI is one of the significant side effects of chemotherapy treatment. Treating breast cancer patients with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide has increased the frequency of survivors, but due to CICI, the life quality of the breast cancer survivors has taken a toll. Understanding the epigenetic factors responsible for CICI can help design a more effective medical intervention for CICI.

Methods and materials

Animal study

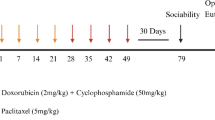

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The City College of New York and was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) for the reporting of animal experiments. Intact female Sprague-Dawley rats at the age of 8–10 weeks were obtained from Charles River. Rats were housed in atemperature controlled colony room (± 21–22 °C), under a 12:12light dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 am) with water and food (Har-lan Teklab Rodent Chow) available ad libitum. For subsequent studies, the rats were divided into two groups: the vehicle (saline treated) group and the experimental (AC-chemotherapy treated) group. We chose Female Sprague-Dawley rats as a tumor free breast cancer model. 8–10 week old rats were used because neuronal development is considered complete at this age and is fully representative of an adult, female brain.

Drug treatments were carried out as previously described16. The rats in the experimental group were intravenously injected once a week for three weeks with the combination of cyclophosphamide (40 mg/kg; LKT Laboratories) and doxorubicin (4 mg/kg; LKT Laboratories) prepared in 0.9% saline solution according to their body weight. The vehicle control animals were administered an equal volume of saline (calculated based on total body weight) each week. The injections were sdministered intravenously in rats tail-vein. The rats were anasthesized with isoflurane in oxygen. For induction 4–5% and to maintain 1–2% isoflurane was used. One week following the last injection, the rats were euthanized by decapitation to collect tissue for subsequent biochemical analyses. Whole brains were rapidly removed, and the prefrontal cortex was isolated on ice from each hemisphere, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C until further processing15. The AC-chemotherapy administration regimen used was already established in prior studies to create a tumor free CICI model15,39.

RNA isolation & qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from approximately 20-25 mg of the prefrontal cortex tissue from each animal using the RNeasy miniprep kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were determined using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher). All RNA samples used in the study obtained A260/A280 ratios that ranged from 1.8 to 2.0.

RNA samples (approximately 200ng) were used to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) using a random hexamer and Superscript III reverse transcriptase enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In addition, mRNA samples isolated from rat PFC tissues were used to synthesize cDNA. Before performing qPCR, the cDNA samples were normalized to 5 ng/µl.

Quantitative PCR amplification of the cDNA (10ng/ well) was carried out with Power Up SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied biosystem) using gene-specific primers. PCR products were monitored using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System, and amplicon specificity was confirmed by melt curve analysis. Fold changes in gene expression relative to saline controls were calculated using the comparative CT method with reference to the housekeeping gene, 18 S. Statistical analysis for each target gene was performed on ΔCT values between saline and chemotherapy-treated groups. The list of primers used is given in Table 1.

DNA isolation, global DNA methylation, and hydroxy-methylation level detection assay

Total DNA was extracted from approximately 20 mg of prefrontal cortex tissue from each animal using a Qiagen DNA isolation kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration and purity were determined using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer). All DNA samples used in the study obtained A260/A280 ratios that ranged from 1.8 to 2.0.

DNA samples were further used for the global DNA methylation assay. 100ng of DNA from each sample was used to determine the global methylation level using Epigentek’s colorimetric MethylFlash Global DNA Methylation (5-mC) ELISA Easy Kit and MethylFlash Global DNA Hydroxy methylation (5-hmC) ELISA Easy Kit. The assay plates were read using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader at 450 nm wavelength.

Nuclear protein isolation, histone acetyl transferase, and histone deacetylase activity assay

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, nuclear protein was extracted from approximately 25 mg of prefrontal cortex tissue from each animal using the EpiQuik Nuclear extraction kit (Epigentek). Protein concentrations were determined using Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit using a 96-well plate. The 96-well plate was read using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader at 565 nm wavelength.

20ng of isolated nuclear protein samples were used for checking histone acetyl transferase activity using colorimetric EpiQuik HAT Activity/Inhibition Assay Kit (EpiGentek) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay plate was read using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader at 450 nm wavelength. Nuclear protein samples were also used for checking histone deacetylase activity using Epigenase HDAC Activity/Inhibition Direct Assay Kit (Colorimetric) from EpiGentek, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay plate was read using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader at 450 and 650 nm wavelengths.

Whole genome bisulfite sequencing

Whole genome bisulfite sequencing, a next-generation technique, was used to detect the DNA methylation landscape throughout the whole genome in doxyorubicin and cyclophosphamide treated animals leading to a change in gene inactivation and activation profiles. DNA samples from both saline-treated and chemotherapy-treated animals were sent to Novogene for whole genome bisulfite sequencing. The library preparation in Novogene followed these steps : DNA sample was first fragmented using Covaris S220. The fragmented DNA was then repaired, dA-tailed and ligated to sequencing adaptors and sunbsequently bisulfite treated using EZ DNA Methylation Gold Kit (Zymo Research). The final DNA library was obtained by size selection and PCR amplification. The sequencing was done in illumina HiSeq/NovaSeq platform.

The sequencing data was also analyzed in Novogene. The raw data was qc checked using Fastqc tool followed by Bismark alignment.

Statistical analysis

Data comparisons were performed using a non-parametric, unpaired, one-tailed T-test. All graphs and statistical results were generated using Graph-pad Prism software. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the SRA repository, with accession number SRR31443702 and SRR31443701. The Reviewer link for our data: https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1189490?reviewer=g5c0b1c0225bgr2p6eb979eret. The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Please contact Karen Hubbard at khubbard@ccny.cuny.edu for data requests.

References

Dietrich, J., Monje, M., Wefel, J. & Meyers, C. Clinical patterns and biological correlates of cognitive dysfunction associated with cancer therapy. Oncologist 13, 1285–1295. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0130 (2008).

Wefel, J. S., Saleeba, A. K., Buzdar, A. U. & Meyers, C. A. Acute and late onset cognitive dysfunction associated with chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer 116, 3348–3356. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25098 (2010).

Wefel, J. S., Kayl, A. E. & Meyers, C. A. Neuropsychological dysfunction associated with cancer and cancer therapies: a conceptual review of an emerging target. Br. J. Cancer. 90, 1691–1696. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601772 (2004).

Ahles, T. A., Root, J. C. & Ryan, E. L. Cancer- and cancer treatment-associated cognitive change: an update on the state of the science. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 3675–3686. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0116 (2012).

Wefel, J. S. & Schagen, S. B. Chemotherapy-related cognitive dysfunction. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 12, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-012-0264-9 (2012).

Vardy, J., Wefel, J. S., Ahles, T., Tannock, I. F. & Schagen, S. B. Cancer and cancer-therapy related cognitive dysfunction: an international perspective from the Venice cognitive workshop. Ann. Oncol. 19, 623–629. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm500 (2008).

Jean-Pierre, P. et al. Prevalence of self-reported memory problems in adult cancer survivors: a National cross-sectional study. J. Oncol. Pract. 8, 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2011.000231 (2012).

Koppelmans, V. et al. Neuropsychological performance in survivors of breast cancer more than 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 1080–1086 (2012).

Calvio, L., Peugeot, M., Bruns, G. L., Todd, B. L. & Feuerstein, M. Measures of cognitive function and work in occupationally active breast cancer survivors. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 52, 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181d0bef7 (2010).

Ahles, T. A. et al. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive changes associated with adjuvant treatment for breast cancer: impact of age and cognitive reserve. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4434–4440. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0827 (2010).

Koppelmans, V. et al. Global and focal white matter integrity in breast cancer survivors 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 889–899. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22221 (2014).

Deeken, J. F. & Loscher, W. The blood-brain barrier and cancer: transporters, treatment, and Trojan horses. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 1663–1674. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2854 (2007).

Dietrich, J., Han, R., Yang, Y., Mayer-Proschel, M. & Noble, M. CNS progenitor cells and oligodendrocytes are targets of chemotherapeutic agents in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. 5, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/jbiol50 (2006).

Mounier, N. M., Abdel-Maged, A. E., Wahdan, S. A., Gad, A. M. & Azab, S. S. Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment (CICI): an overview of etiology and pathogenesis. Life Sci. 258, 118071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118071 (2020).

Salas-Ramirez, K. Y. et al. Doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide induce cognitive dysfunction and activate the ERK and AKT signaling pathways. Behav. Brain Res. 292, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2015.06.028 (2015).

Bagnall-Moreau, C., Chaudhry, S., Salas-Ramirez, K., Ahles, T. & Hubbard, K. J. M. n. Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment is associated with increased inflammation and oxidative damage in the hippocampus. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 7159–7172 (2019).

Briones, T. L. & Woods, J. J. B. N. Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment is associated with decreases in cell proliferation and histone modifications. BMC Neurosci. 12, 1–13 (2011).

Kovalchuk, A. et al. Sex-specific effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy agents cyclophospha-mide and mitomycin C on gene expression, oxidative DNA damage, and epigenetic alterations in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus–an aging connection. Aging 8, 697 (2016).

McAlpin, B. R. et al. HDAC6 Inhibition reverses long-term doxorubicin-induced cognitive dysfunction by restoring microglia homeostasis and synaptic integrity. Theranostics 12, 603 (2022).

Bestor, T. H. The DNA methyltransferases of mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2395–2402. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/9.16.2395 (2000).

Yoder, J. A., Soman, N. S., Verdine, G. L. & Bestor, T. H. DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferases in mouse cells and tissues. Studies with a mechanism-based probe. J. Mol. Biol. 270, 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1997.1125 (1997).

Tahiliani, M. et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science 324, 930–935. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170116 (2009).

Richa, R. & Sinha, R. P. Hydroxymethylation of DNA: an epigenetic marker. EXCLI J. 13, 592–610 (2014).

Kato, T. & Iwamoto, K. Comprehensive DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation analysis in the human brain and its implication in mental disorders. Neuropharmacology 80, 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.12.019 (2014).

Meehan, R. R., Lewis, J. D. & Bird, A. P. Characterization of MeCP2, a vertebrate DNA binding protein with affinity for methylated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 5085–5092. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/20.19.5085 (1992).

Guy, J., Cheval, H., Selfridge, J. & Bird, A. The role of MeCP2 in the brain. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 27, 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154121 (2011).

Rajavelu, A. et al. Chromatin-dependent allosteric regulation of DNMT3A activity by MeCP2. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 9044–9056. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky715 (2018).

Ben-Shachar, S., Chahrour, M., Thaller, C., Shaw, C. A. & Zoghbi, H. Y. Mouse models of MeCP2 disorders share gene expression changes in the cerebellum and hypothalamus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 2431–2442. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddp181 (2009).

Kaas, G. A. et al. TET1 controls CNS 5-methylcytosine hydroxylation, active DNA demethylation, gene transcription, and memory formation. Neuron 79, 1086–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.08.032 (2013).

Guo, J. U. et al. Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3607 (2014).

Chen, J., Park, C. S. & Tang, S. J. Activity-dependent synaptic Wnt release regulates hippocampal long term potentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11910–11916. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M511920200 (2006).

Tiwari, S. K. et al. Curcumin-loaded nanoparticles potently induce adult neurogenesis and reverse cognitive deficits in alzheimer’s disease model via canonical Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. ACS Nano. 8, 76–103. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn405077y (2014).

Krestinina, O. et al. In aging, the vulnerability of rat brain mitochondria is enhanced due to reduced level of 2′, 3′-cyclic nucleotide-3′-phosphodiesterase (CNP) and subsequently increased permeability transition in brain mitochondria in old animals. Neurochem. Int. 80, 41–50 (2015).

Azarashvili, T. et al. Ca2+-dependent permeability transition regulation in rat brain mitochondria by 2’,3’-cyclic nucleotides and 2’,3’-cyclic nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 296, C1428–1439. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00006.2009 (2009).

Schnaar, R. L. & Lopez, P. H. Myelin-associated glycoprotein and its axonal receptors. J. Neurosci. Res. 87, 3267–3276. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.21992 (2009).

Rouaux, C., Loeffler, J. P. & Boutillier, A. L. J. B. P. Targeting CREB-binding P.otein (CBP) loss of function as a therapeutic strategy in neurological disorders. Biochem. Pharmacol. 68, 1157–1164 (2004).

Johannessen, M., Delghandi, M. P. & Moens, U. J. C. A. What Turns CREB On?? Cell. Signal. 16, 1211–1227 (2004).

Mayr, B. & Montminy, M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2, 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1038/35085068 (2001).

Macleod, J. E. et al. Cancer chemotherapy impairs contextual but not cue-specific fear memory. Behav. Brain Res. 181, 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2007.04.003 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Harry Acosta, Director of Animal Facility, CCNY for his valuable help with animal handling in this current study. The authors wish to thank funding from the NIH/NCI grant U54CA132378 and U54 CA137788 to TA, KSR, and KH; NIH/ RISEGM08168 grant to CB; and NIH/RCMI grant 5G12MD007603 to KH and KSR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. S.C. wrote the first draft of the manuscript.S.C. , C.W. , C.B.M, F.U. and J.R. contributed to material preparation, data collection and analysis. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chakrabarti, S., Wagh, C., Bagnall-Moreau, C. et al. Chemotherapy treatment alters DNA methylation patterns in the prefrontal cortex of female rat brain. Sci Rep 15, 20681 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07419-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07419-2