Abstract

Predation of immature monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) by arthropod natural enemies is well-established. However, little is known about predation by avian and mammalian predators on this species. Decline of the monarch over the last several decades has led to numerous conservation programs and efforts to plant milkweed and floral resources in diverse habitats. The recent proposal to list the monarch as a threatened species may require non-lethal methods for studying predation dynamics. Here, artificial caterpillar models were used to assess predation of late instar monarchs in urban, peri-urban, and rural milkweed stands. Impressions on the larval models left behind by arthropod, avian, and mammalian natural enemies reveal higher instances of predation in rural areas. Predation by arthropods increased from May-late July and diminished in August and September. Avian predation was highest in May-early June, with an uptick in September, and rarely occurred in late July-early August. Mammalian predation was minimal. This study suggests that artificial larva can be used to study predation of a conspicuous species of conservation concern, such as the monarch, although inherent methodological limitations should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) has been at the forefront of pollinator conservation initiatives1,2,3,4,5,6 due to its decline over the last several decades7,8. This decline has been attributed to loss of habitat, decreasing abundance of milkweed (Asclepias spp.) host plants, and use of pesticides9. Conservation of this iconic butterfly has spurred tremendous support from all land-use sectors through reconciliation ecology, garden and habitat establishment, educational programming, and public awareness10,11. The low overwintering counts in 2013–201412 led to the creation of many pollinator conservation initiatives that still see support today. As of December 2024, a proposed rule by USFWS to list the monarch butterfly as a threatened species under Sect. 4(d) of the Endangered Species Act13 has been published, with a final decision expected in early 2026. This proposal calls for federal protections and highlights the need for conservation and research exploring poorly understood mortality factors (e.g., predation by vertebrate predators).

Most of the studies to date that explore the monarch predator-prey complex provide evidence that focuses predominately on arthropod natural enemies. Arthropod predators regularly utilize monarchs as prey in the wild. Predation of eggs and neonate larvae have been observed in both field and laboratory settings by various arthropod taxa including Araneae, Coleoptera, Dermaptera, Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, Neuroptera, Opiliones, and Orthoptera14. Survival of monarchs from egg to 5th instar is estimated around 10%, whereas survival from 5th instar to adult is as high as 90%15,16. By excluding terrestrial and aerial natural enemies, one study found survival significantly increased from egg to 1 st instar larva17. This study also observed that aphid presence on milkweed may increase the abundance of generalist predators (e.g. ants) and lead to more instances of predation. In addition to native natural enemies, several instances of non-native predators interacting with monarch larvae have been documented. The red imported fire ant (S. invicta)18, European paper wasp (P. dominula)19, Chinese mantids (T. sinensis)20, and multicolored Asian ladybeetles (H. axyridis)21 have been reported to prey on monarch larvae. Of these non-native predators, two have been observed to excise the digestive tract of monarch larvae, presumably to avoid ingested cardenolides (cardiac-active steroids sequestered from host plants by monarchs that are generally toxic to most animals)20. Interactions with non-native or invasive predators, beyond the already high rates of predation by native natural enemies, may pose additional predation pressures or lead to instances of ecological traps19.

Although arthropod predation of monarchs is well-studied, little is known about avian and mammalian predation, especially on immature stages. Some limited past work examining predation of wild adult monarchs at the overwintering grounds demonstrated that two species of birds can consume large numbers of monarchs each day, resulting in predation of up to 9% of the population throughout the entire overwintering cycle22. These avian predators tended to preferentially feed on male butterflies, but the researchers did not determine if fat, or cardenolide content, or some other factor was driving this preference23. In addition to avian predators, several species of mice were observed to feed on adult monarch butterflies at the overwintering grounds24. Predation was documented in both the field and lab settings and cardenolide concentration of the prey did not seem to influence prey acceptance. The few records of avian and mammalian predation on wild adult monarchs occurred at the North American overwintering grounds. However, no vertebrate predation has been reported on any wild immature life stage or documented in the breeding grounds.

Artificial larval models have been used to assess predation pressure by avian, mammalian, and arthropod natural enemies in diverse habitats25,26,27,28,29,30,31. The use of artificial larvae allows researchers to deploy large numbers of models in a convenient and cost-effective manner, especially in cases where direct observation may be cost-prohibitive, or impractical. However, this methodology is not without inherent limitations32. The immobility of larval models, lack of visual and olfactory cues (e.g., defoliation33, frass, and plant volatiles)34, placement on a substrate, materials of which models are made35, and habituation by predators to artificial prey may lead to conclusions not wholly representative of actual predation rates30. Impressions left from predation events may be misinterpreted or not included in analysis because they are unclear. Identification to coarse taxonomic levels (e.g., arthropod, avian, and mammal) has proven to be reliable but resolution to lower taxonomic levels is inconsistent32. Previous predation studies using live monarch larvae have relied on observation under laboratory conditions, passive assessment, or limited direct observation in the field14,15,16,17,18. To date, no study has recorded predation of monarch larvae by avian or mammalian predators. In an effort to address this knowledge gap, we employed this method herein. In addition to the relative predation data this methodology provides, it may be a valuable tool for studying species of conservation concern, such as the monarch, because of its non-lethal approach.

Predation rates of model caterpillars are higher in areas near intact forest and lower in urban areas with greater numbers of structures and impenetrable surfaces36,37,38, suggesting that fragmentation due to urbanization may lead to a disruption of trophic interactions. Another study looking at caterpillar predation observed more attacks on larger prey but also greater instances of attacks on conspicuous prey39. Coloration and size may make prey more visually apparent and thus increase instances of predation by predators relying on visual cues40. When exposed to artificial insect models, dragonflies did not preferentially attack conspicuous (yellow and black striped) or cryptic artificial prey41. However, the frequency of attacks was influenced by size of prey, where smaller models were attacked at higher rates, suggesting a strong correlation between prey size and instances of attacks by this predator group. In tropical systems, where arthropods are the dominant predators of lepidopteran larvae, instances of attacks tended to be higher on smaller models42,43,44. Whereas in temperate systems, where avian predation is more prevalent, larger models are more likely to be attacked45,46. Researchers found that the materials used to make larval models (clay vs. dough) influenced predation rates by arthropod predators, but size, color, and host plant of deployment did not35.

Monarch butterflies encounter generalist predators across their range in natural, urban, and agricultural landscapes. Predation pressure may vary depending on the surrounding botanical communities and urbanization26,36,37. In cases where native natural enemies sympatrically interact with related non-native species, top-down cascading effects on food webs may occur47,48,49. These interactions may also increase predation pressures in urban areas where predation is generally lower37.

Previous studies on monarch predation have used live adult butterflies, larvae, or sentinel eggs and focused on arthropod natural enemies. All of the documented predation by avian and mammalian predators of wild monarchs took place at the overwintering grounds in central Mexico and occurred on adult butterflies22,24. To date, artificial larval models, which have the potential to capture multi-taxa predation data more representatively, have not been used to assess predation of an aposematic larva of conservation concern such as the monarch. In addition to the advantages of cost and practicality of larval models, the proposed federal listing may call for the use of non-lethal methods for studying monarch butterflies in the future. The purpose of this study was to explore the relative proportion of predator-prey interactions among arthropods, birds, and mammals in habitats with varying degrees of urbanization to inform monarch butterfly conservation strategies, initiatives, models, and discussions.

Results

Attacks on artificial larval models in urban, peri-urban, and rural milkweed plantings

Late 3rd and early 4th instar larval models were assessed for predation by examining impressions left behind by predators (Fig. 1) in urban, peri-urban, and rural milkweed plantings in Kentucky, USA (KY) and Ohio, USA (OH) in 2021 and 2023 respectively. In KY, of the 620 larval models deployed, 7.42% were verified to be attacked by arthropod (4.68%) and avian (2.74%) predators (Fig. 2A). No mammalian attacks were explicitly identified in 2021. An additional 5.97% (N = 37) were missing from the plants. The cause of the missing models is unknown but could have been due to removal from a larger predator (avian or mammalian), been dislodged by natural forces, or tampered with and removed. If considering the missing larvae as ‘preyed upon’, this would result in 13.38% total predation throughout the duration of the study. However, missing larvae were not included in any of the analyses. In OH, of the 1130 larval models deployed, 4.96% were verified to be preyed upon by arthropod (2.83%), avian (2.04%), and mammalian (0.09%) predators (Fig. 2B). An additional 2.06% of larval models were missing from the plants. Instances of predation events differed with the proportion of hardscape. Arthropod predation was significantly higher in rural milkweed plantings than in urban sites in 2021 (F(2.42) = 5.05, P = 0.008) and 2023 (F (2,17) = 3.26, P = 0.05) (Fig. 2). Avian predation was not significantly different in rural, peri-urban, or urban sites but tended to be higher in more rural sites in 2021 (F(2.48) = 1.64, P = 0.08) and in 2023 (F(2.21) = 3.26, P = 0.05).

Construction of artificial larval models, indentions by predators, and field examples. (A) Rolling of plasticine to create artificial larval models, (B) twisting to create striations that resemble monarch larvae, (C) finished model deployed on common milkweed, D-F) examples of impressions left by arthropod predators, G-H) beak indentions from avian predators, I-J) common milkweed stem damaged from an attack by an avian predator and recovered model, K) impressions left by mammalian predator, L) example of ‘missing’ model with no indication of predator identity.

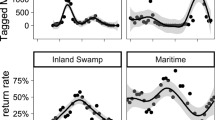

Mean attacks on artificial larval models by avian and arthropod predators during 72 h observation periods in urban, peri-urban, and rural milkweed plantings. (A) Mean predation events from May-September 2021, (B) Mean predation events from May-September 2023. All data represented as Mean ± SE. Capital letters indicate significant differences within the avian group. Lower case letters indicate significant differences within the arthropod group.

Prevalence of attacks by sampling date

The numbers of attacks on artificial larvae varied by the sampling date in both KY in 2021 and OH in 2023. In KY, attacks by arthropod predators increased throughout spring and summer with May accounting for 20.6%, June for 30.2%, and July being the highest with 36.8% (Fig. 3A). Attacks were low in August and September, accounting for 12.5% of attacks. Total attacks by arthropod predator by sampling date (May, June, July, August, September) in urban plantings accounted for (5.4%, 8.6%, 8.6%, 0%, 0%), in peri-urban gardens (5.4%, 8.6%, 10.8, 0%, 3.5%), and rural plantings (9.8%, 13%, 17.4%, 6.9%, 0%) respectively. The majority of the attacks by avian predators took place in May (27.5%), June (39.1%), and September (27.5%) (Fig. 3A). No predation by avian predators was recorded in July and low numbers of attacks were recorded in August (5.9%). Total attacks by avian predators by sampling date in urban plantings accounted for (10.8%, 5.9%, 0%, 0%, 10.8%) attacks, in peri-urban gardens (5.9%, 16.6%, 0%, 0%, 5.9%), and rural plantings (10.8%, 16.6%, 0%, 5.9%, 10.8%) respectively. There were no attacks by mammalian predators in 2021.

In OH, arthropod predation was highest in the latter part of the season. In July arthropod attacks accounted for (37.5%), in August (18.75%), and September (18.75%) (Fig. 3B). Spring predation was lower in May and June, each accounting for 12.5% of attacks. Total attacks by arthropod predators by sampling date (May 27–30, June 9–12, June 23–26, July 7–10, July 21–24, August 1–4, August 14–17, September 5–8) in urban plantings accounted for (0%, 0%,0%, 4.3%, 0%, 4.3%, 0%,4.3%), in peri-urban gardens (6.3%,4.3%, 4.3%, 4.3%, 4.3%, 0%, 4.3%, 4.3%), and rural plantings (6.3%, 0%, 12.1%, 12.1%, 12.1%, 0%, 8.6%,8.6%) respectively. Attacks from avian predators were highest in the spring and heading into fall (Fig. 3B). June accounted for 38.82% and both May and September with 25.74%. Attacks in July and August were low, each accounting for 4.35%. Total attacks by avian predators in urban plantings by sampling date (May 27–30, June 9–12, June 23–26, July 7–10, July 21–24, August 1–4, August 14–17, September 5–8) accounted for (4.36%, 0%, 0%, 4.36%, 4.36%, 0%, 0%, 8.7%), in peri-urban gardens (8.7%, 8.7%, 4.36%, 4.36%, 0%, 0%, 4.36%, 4.36%), and rural plantings (8.7%, 17.26%, 8.7%, 4.36%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 4.36%) respectively. The only confirmed mammalian attack occurred in September (0.09%).

Discussion

Arthropod natural enemies are abundant in most temperate ecosystems where they exert strong selective pressure on lepidopteran larvae16,17,18,19,48. This study provides evidence that builds upon this well-documented relationship, albeit using artificial caterpillar models, and suggests that avian and mammalian predation of late instar monarch larvae in the North American breeding grounds may occur. Higher proportions of urbanization surrounding milkweed plantings led to a decrease in instances of arthropod attacks (Fig. 2). Although predation tended to be higher in rural and peri-urban habitats for both arthropod and avian predators, attacks by birds were statistically similar within all habitat types. The size of the larvae that were deployed throughout the study (~ 4th instar) and the conspicuous coloration of the models may have influenced attack rates. Visually apparent models may be attacked at higher rates by predators using visual cues to locate prey. If smaller models (1st and 2nd instars) were used there would likely be an increase in instances of attacks by arthropods, where prey-size fidelity may exist, and a decrease in avian predation events39,40,41,45,46. The substrate upon which the larvae are presented may also influence predation rates. Attacks on caterpillars presented on the canopy of a plant or tree may receive greater predation by birds44, whereas higher levels of predation by arthropods and mammals are expected at ground-level30. Insectivorous birds can forage thousands of meters away from their breeding habitat50. Urban and peri-urban green spaces with suitable prey near intact breeding habitat may explain the similar levels of predation that we observed51. Arthropod predation tended to build and peak in mid-July to early August, whereas avian predation was highest in spring and late summer. Fluctuations in population growth and abundance of predatory arthropods throughout the growing season, which generally cycle with herbivorous insect populations, may explain this trend52,53,54. Seasonal protein, calcium, and carotenoid requirements of birds and their nestlings may explain the uptick in predation in the early and late season55,56.

There was only a single verified predation event by a mammalian predator. This is likely due to the placement of the larvae on the top third of the plant where it would be difficult for such predators to have access. Models on the lower portions of the plant or on the ground (simulating movement between plants or to pupation sites) may receive greater instances of attacks from mammalian predators30. There was not enough predation by mammals in this study to draw any meaningful inferences on seasonal predation rates or trends. Predation by mammalian predators may be higher than expected and the substrate upon which the model is presented, prey mobility, odors, and materials used in creation may influence these rates.

In this study, relative predation observed may have been influenced by the use of artificial models. Predation attempts on larval models may not lead to actual predation events. Live larvae can escape predation by dropping to the ground, hiding, or thrashing19. The size of larval models, that were chosen to elicit attacks from the broadest suite of predators, may have influenced attack rates40. The substrate and the placement of the models on the top side of the leaf, and on the top third of the plant, may be better suited for certain predator groups30. The absence of herbivore (or mechanically) damaged leaves may decrease levels of avian predation compared to prey on branches with intact leaves33. Avian predators may use defoliation as a cue for the presence of prey. Conspicuous larvae may be easier for visual foraging predators to discover and thus experience higher levels of predation than cryptic prey. Length of exposure of models to predators and substrate they are presented on may lead to habituation30, thus deflating actual predation rates. Aposematic larval models that are not chemically defended by sequestered plant toxins may receive inflated rates of attack. Combining larval models with visual and olfactory cues that predators use while foraging for prey may influence attack rates. Although there are inherent limitations, this method merits further investigation.

Studies conducted at the eastern migratory monarch overwintering grounds demonstrate that avian predators feed on adult butterflies22,23 but no evidence has been documented in the literature of reproductive monarchs of any life stage being fed on by avian predators. Several additional studies explored the palatability of monarchs by avian predators57,58,59. Adult male butterflies, late instar larvae, and prepupae larvae that were reared on either cabbage (Brassica spp.) or tropical milkweed (A. curassavica), were fed to blue jays (C. cristata) and their reactions were recorded53. Birds rejected the aposematic insects at first, but after feeding on cabbage-reared monarchs the jays readily accepted them because they caused no ill effects, whereas monarchs reared on milkweed, caused the jays to become sick and vomit60. In a subsequent study, birds were fed a powder made from dried adult male butterflies reared on different species of milkweed with varying concentrations of cardenolides and a palatability spectrum was observed58. Monarchs reared on milkweed with higher concentrations of cardenolides were more likely to induce illness in the birds, whereas those reared on lower concentration host plants resulted in no-such ill effect. Brower’s work at the overwintering grounds may be the reason why predation by avian predators has been overlooked in studies conducted in the North American breeding grounds.

If naïve avian predators need to experience interactions with unpalatable prey, such as monarchs reared on host plants with high concentrations of cardenolides, to acquire the associative learning that leads to avoidance/rejection, then there is still a portion of the monarch population that may be fed upon each season to meet this condition. Wild birds may be able to eat monarchs with low cardiac glycoside toxicity and experience no detrimental effects. If found acceptable, such prey may even be targeted by avian predators. Avian predators may avoid monarch butterflies due to their sequestration of cardenolides and not necessarily by aposematic coloration alone. Regardless of the numbers consumed, pressure in addition to native arthropod natural enemies16,17,42, invasive/non-native predators19,20,21, pesticides61 and other anthropogenic mortality factors62,63 may be detrimental to monarch populations. As naïve birds each year engage in this associative learning that leads to avoidance of aposematic prey items, appropriate levels of cardenolides need to be present within the prey to meet those conditions.

The dominant species of milkweed vary by region and habitat. Species distribution may be influenced by soils, temperature, topography, and precipitation64. Levels of predation may be higher in areas of the US where the dominant species of milkweed is one with low concentrations of cardenolides65,66. Climatic variations or stressors can also influence cardenolide concentrations in some species67. Specialist herbivores may also experience varying levels of cardenolides depending on the part of the plant upon which they fed. Leaves, roots, stems, and reproductive parts of the plant express different concentrations within the plant68,69. Depending on the region, species, and the plant parts consumed by the herbivore, expression of sequestered cardenolides and effects on herbivores likely vary70,71,72. Cultivars of species may express levels differ from their wild-type counterparts73. Because of this variation, a palatability spectrum may be influencing avian predation rates of monarch adults and larvae. Predation pressure may be lower by insectivorous birds foraging on monarch larva feeding host plants with high concentrations of cardenolides (e.g., A. cusassavica in the gulf states). However, in this study, larval models were presented on A. syricaca and A. incarnata, two species with low concentrations of cardenolides70, which may have influenced predation rates. Consideration of this interaction should be given more thought in the design, species selection, and implementation of conservation habitats.

As the listing decision for the monarch butterfly approaches, the need for more research and its application in conservation habitats has never been more apparent. The finding from the USFWS monarch butterfly Species Status Assessment report predicted probability of extirpation by 2080 as 56–79% for the eastern migratory population and 99% for the western population74. Studies that lead to the development of best management practices or actionable science for monarch butterfly habitat and conservation efforts are needed now more than ever.

Methods

In 2021 and 2023, artificial larval models were deployed on public and private properties including residential homes, parks, schools, and gardens along an urban/rural gradient on planted and naturally occurring milkweed. To categorize milkweed plantings (urban, peri-urban, rural), satellite images and the Measure Tool feature of Google Earth Pro geospatial software (Google, Palo Alto CA) were used to estimate the ratio of impervious to pervious surfaces in 100 m radius centered on each planting (Fig. 4). Urban plantings were categorized by having > 70% coverage by structures and impenetrable surfaces, peri-urban with 31–69% coverage, and rural as < 30% coverage by impenetrable surfaces. The distance between study sites ranged from 1.74 to 67.71 km. Plant communities varied among sites. Urban plantings generally included ornamental forbs (e.g., lilies, zinnia, baptisia). Peri-urban, rural sites, and some of the urban sites resembled more naturalized plantings, with milkweeds intermixed with tall fescue, rudbeckia, bergamot, and occasionally weedy non-native species (e.g., Canadian thistle, cutleaf teasel, Queen Anne’s lace).

Locations1 of milkweed plantings in 2021 and 2023. A) Counties of observation (green star on state map2) in 2021 and locations of urban (red), peri-urban (orange), and rural (yellow) study sites. B-D) examples of urban, peri-urban, and rural milkweed plantings in KY respectively, E) Counties of observation (green star on state map3) in 2023 and locations of urban (red), peri-urban (orange), and rural (yellow) study sites. F-H) Examples of urban, peri-urban, and rural milkweed plantings in OH. 1Satellite images: Google Earth Pro Ver. 7.3 https://www.google.com/earth/about/versions/#download-pro. 2Image credit: David Benbennick https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Map of Ohio highlighting Summit_County.svg 3David Benbennick https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Map_of_Kentucky_highlighting_Fayette_County.svg.

Models were made in the lab by rolling out three colors (black, white, and yellow) of non-toxic plasticine (Sargent Art, Hazleton, PA), combining them together, and then twisting to create striations resembling monarch butterfly larvae (Fig. 5). Larval models were approximately 5 × 30 mm to mimic late third or early fourth instar larvae. This model size was chosen due to the ease and consistency of model creation. In addition, we wanted to use a mid-sized model that would illicit attacks from varying predator groups (e.g., arthropods, birds, and mammals). Artificial larvae were affixed to adaxial surface of milkweed (A. syriaca and A. incarnata) leaves with a pin on the proximal end (nearest to the stem) and a small piece of cork (5 × 5 mm) to secure them in place. The same species of milkweed were used in both years. To confirm that models would remain affixed, in the absence of any predation attempts, potted plants with artificial larvae attached were placed in the field in clear mesh tents on days when the temperature was > 27 °C, to exclude any predators, and left for 72 h. All larvae remained on plants during this observation period. In the field, models were affixed to a leaf on the top third of the plant. The models were left in place for 72 h before being collected and transported to the lab where they were visually inspected for damage by arthropod, avian, and mammalian predators. Artificial larvae were transported in plastic cups with cotton balls to provide cushioning so they would remain intact and undamaged.

Comparison of live monarch caterpillar and artificial larval model. (A) Live monarch larvae* on milkweed (B) Artificial larval model on common milkweed (A. syriaca). *Photo credit: ShenandoahNPS https://flickr.com/photos/67015038@N06/51833131622.

To identify impressions on the model caterpillars we used the methods and examples described in Sam et al. (2014)49 and used a coarse taxonomic resolution (e.g., arthropod, bird, mammal). Arthropod attacks were characterized by paired or singular mandible holes, scratches, indentions from legs, maceration, and slits. Avian predation resulted in U or V-shaped damage on both sides of the larval models, sections that were removed with a sharp angle, impressions from the upper mandible, and prey that were recovered from the ground with damage as above. Avian attacks were occasionally accompanied by damage to the plant. Mammalian attacks were characterized by impressions made from teeth. Any unidentifiable impressions (e.g., impressions that may have been obscured due to multiple attacks) or impressions suspected to be caused in transport/collection were not included in the analysis.

The number of models deployed at each site was dependent on the concentration of milkweed plants. In 2021, larvae were deployed at 9 locations including Monarch Waystations in urban areas (N = 3), rural meadow plantings (N = 3), and milkweed stands in peri-urban parks and arboretums (N = 3) in north central KY. Artificial models were deployed once a month from May to September (N = 620). In 2023, models were deployed at 13 locations in NE Ohio (5 urban, 3 peri-urban, 5 rural). Models were deployed once in May and September and twice a month from June-August, during peak monarch breeding season in OH. Observations were concluded after the first September sampling date when milkweed began to senesce. The original study was set to begin in KY in 2020 but due to travel restrictions related to the pandemic it was set back a year. In 2021, after the researcher had relocated to NE OH, previously approved KY sites were used only once a month for logistical reasons. Only one larva were deployed per plant and evenly dispersed throughout the planting. The total number of models deployed in 2023 was 1130.

The mean predation events were pooled across all sampling dates for habitat type (urban, peri-urban, and rural) and were independently analyzed by predator group (arthropod and avian) using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for a completely randomized design. Mean separation using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) to test when overall treatment effect was significant (p < 0.05) were performed. Analyses were performed using Statistix 10 (Analytical Software, Boca Raton, FL)75. Data met normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions. Data is reported as means ± standard error.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

MonarchWatch Monarch waystations (2025). https://www.monarchwatch.org/waystations/

Monarch Joint Venture. Programs https://monarchjointventure.org/mjvprograms. (2025).

Journey North. Integrated monarch monitoring program (2025). https://monarchjointventure.org/mjvprograms/science/integrated-monarch-monitoring-program

Project Monarch Health - University of Georgia. Monitoring (2025). https://www.monarchparasites.org/monitoring

Pollinator Health Task Force. National strategy to promote the health of honey bees and other pollinators (2015). >https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/ Pollinator%20Health%20Strategy%202015.pdf

National Pollinator Garden Network. Million pollinator garden challenge (2019). http://millionpollinatorgardens.org/

Brower, L. P. et al. Decline of monarch butterflies overwintering in mexico: is the migratory phenomenon at risk? Insect Conserv. Divers. 5, 95–100 (2012).

Thogmartin, W. E. et al. Monarch butterfly population decline in North america: identifying the threatening processes. Royal Soc. Open. Science. 4 https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.3876100 (2017).

ThogmartinW.E. et al. Restoring monarch butterfly habitat in the Midwestern US: ‘all hands on deck’. Environ. Res. Lett. 12 (07405 10). 1088/1748–9326/aa7637 (2017).

Audubon International. Monarchs in the rough https (2025). ://www.auduboninternational.org/monarchs-in-the-rough

Rights-of-way as Habitat Working Group – University of Illinois. Nationwide CCAA Monarch Butterfly (2025). https://rightofway.erc.uic.edu/national-monarch-ccaa/

Rendón-Salinas, E., Fajardo-Arroyo, A. & Tavera-Alonso, G. Forest surface occupied by monarch butterfly hibernation colonies in December - World Wildlife Fund (2014). http://assets.worldwildlife.org/publications/768/files/original/REPORT_Monarch_Butterfly_colonies_Winter_2014.pdf?1422378439 (2015).

USFWS. Fish and Wildlife Service proposes Endangered Species Act protection for monarch butterfly; Urges increased public engagement to help save the species (2024). https://www.fws.gov/press-release/2024-12/monarch-butterfly-proposed-endangered-species-act-protection?blm_aid=389388517

Hermann, S. L., Blackledge, C., Hann, N. L., Myers, A. T. & Landis, D. A. Predators of monarch butterfly eggs and neonate larvae are more diverse than previously recognized. Sci. Rep. 9, 14304 (2019).

Nail, K. R., Stenoien, C. & Oberhauser, K. S. Immature monarch survival: effects of site characteristics, density, and time. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 108, 680–690 (2015).

De Anda, A. & Oberhauser, K. S. Invertebrate natural enemies and stage-specific natural mortality rates of monarch eggs and larvae. Monarchs in a Changing World: Biology and Conservation of an Iconic Butterfly (ed. Oberahuser, K., Nail, K., Altizer, S) 60–70 (Cornell University Press, (2015).

Prysby, M. D. Natural enemies and survival of monarch eggs and larvae. Monarchs in a Changing World: Biology and Conservation of an Iconic Butterfly (ed. Oberahuser, K., Nail, K., Altizer, S.) 60–70 (Cornell University Press, 2015).

Hudman, K. L., Stevenson, M., Contreras, K., Scott, A. & Kopachena, J. G. Experimental suppression of red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) has little impact on the survival of eggs to third instar of spring-generation monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) due to buffering effects of host-plant arthropods. Diversity 15, 331; (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/d15030331

Baker, A. M. & Potter, D. A. Invasive paper Wasp turns urban pollinator gardens into ecological traps for monarch butterfly larvae. Sci. Rep. 10, 9553 (2020).

Rafter, J. L., Agrawal, A. A. & Preisser, E. L. Chinese mantids gut toxic monarch caterpillars: avoidance of prey defense? Ecol. Entomol. 38, 76–78 (2013).

Koch, R. L., Hutchison, W. D., Venette, R. C. & Heimpel, G. E. Susceptibility of immature monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus (Lepidoptera: nymphalidae: Danainae), to predation by Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Biol. Control. 28, 265–270 (2003).

Brower, L. P. & Calvert, W. H. Foraging dynamics of bird predators on overwintering monarch butterflies in Mexico. Evolution 39, 852–868 (1985).

Brower, L. P. & Fink, L. S. A natural toxic defense system: cardenolides in butterflies versus birds. Annals New. York Acad. Sciences 443, 171–188 (1985).

Brower, L. P., Horner, B. E., Marty, M. A., Moffitt, C. M. & Villa-R, B. Mice (Peromyscus maniculatus, P. spicilegus, and Microtus mexicanus) as predators of overwintering monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) in Mexico. Biotropica 17, 89–99 (1985).

Bateman, P. W., Fleming, P. A. & Wolfe, A. K. A different kind of ecological modelling: the use of clay model organisms to explore predator–prey interactions in vertebrates. J. Zool. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzo.12415 (2016).

Curtis, R. et. Al. Clay caterpillar whodunit: A customizable method for studying predator-prey interactions in the field. Am. Biology Teacher. 75, 47–51 (2013).

Nason, L. D. Caterpillar survival in the city: attack rates on model lepidopteran larvae along an urban-rural gradient show no increase in predation with increasing urban intensity. Urban Ecosyst. 24, 1129–1140 (2021).

Roeder, K. A. Importance of color for artificial clay caterpillars as Sentinel prey in maize, soybean, and prairie. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 171, 68–72 (2023).

Khan, F. Z. A. & Joseph, S. V. Influence of the color, shape, and size of the clay model on arthropod interactions in turfgrass. J. Insect Sci. 21, 1–15 (2021).

Ferrante, M., Barone, G., Kiss, M., Bozone-Borbath, E. & Lovei, G. L. Ground-level predation on artificial caterpillars indicates no enemy-free time for lepidopteran larvae. Community Ecol. 18, 280–286 (2017).

Molleman, F., Remmel, T. & Sam, K. Phenology of predation on insects in a tropical forest: Temporal variation in attack rate on dummy caterpillars. Biotropica 48, 229–236 (2016).

Low, P. A., Sam, K., McArthur, C., Posa, M. & Hochuli, D. F. Determining predator identity from attack marks left in model caterpillars: guidelines for best practice. Entomol. Expertimentalis Et Appl. 152, 120–126 (2014).

Sam, K., Koane, B. & Novotny, V. Herbivore damage increases avian and ant predation of caterpillars on trees along a complete elevational forest gradient in Papua new Guinea. Ecography 38, 293–300 (2015).

Howe, A., Lovei, G. L. & Nachman, G. Dummy caterpillars as a simple method to assess predation rates on invertebrates in a tropical agroecosystem. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 131, 3 (2009).

Sam, K., Remmel, T. & Molleman, F. Material affects attack rates on dummy caterpillars in tropical forest where arthropod predators dominate: an experiment using clay and dough dummies with green colourants on various plant species. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 157, 317–324 (2015).

Pena, J. C., Aoki-Gonclaves, F., Dattilo, W., Ribeiro, M. C. & MacGregor-Fors, I. Caterpillars’ natural enemies and attack probability in an urbanization intensity gradient across a Neotropical streetscape. Ecol. Ind. 128, 107851 (2021).

Long, L. C. & Frank, S. D. Risk of bird predation and defoliating insect abundance are greater in urban forest fragments than street trees. Urban Ecosyst. 23, 519–531 (2020).

Remmel, T. & Tammaru, T. Size-dépendent predation risk in tree-feeding insects with different colouration strategies: a field experiment. J. Anim. Ecol. 78, 973–980 (2009).

Aslam, M., Oldrich, N. & Sam, K. Attacks by predators on artificial cryptic and aposematic insect larvae. Entomologia Exp. Et Applicata 168, 184–190 (2020).

Duong, T. M., Gomez, A. B. & Sherratt, T. N. Response of adult dragonflies to artificial prey of different size and colour. PLOS One. 12, 0179483 (2017).

Seifert, C. L., Lehner, L., Adams, M. O. & Fiedler, K. Predation on artificial caterpillars is higher in countryside than near-natural forest habitat in lowland south-western Costa Rica. Journal of Tropical Ecology 31, 281–284 (2015).

Holldobler, B. & Wilson, E. O. The Ants (Springer, 1990).

Molleman, F. & Safian, S. Predation on insects on tiwai, Sierra Leone. Entomol. Berichten. 75, 15–21 (2015).

Remmel, T., Tammaru, T. & Magi, M. Seasonal mortality trends in tree-feeding insects: a field experiment. Ecol. Entomol. 34, 98–106 (2009).

Drozdova, M., Sipos, J. & Drozd, P. Key factors affecting the predation risk on insects on leaves in temperate floodplain forest. Eur. J. Entomol. 110, 469–476 (2013).

Mappes, J., Kokko, H., Ojala, K. & Lindstrom, L. Seasonal changes in predator community switch the direction of selection for prey defences. Nat. Commun. 5, 5016 (2014).

Ritcher, M. R. Social Wasp (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) foraging behavior. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 45, 121–150 (2000).

Oberhauser, K. S. et al. Lacewings, wasps, and flies – oh my: insect enemies take a bite out of monarchs. Monarchs in a changing world: Biology and conservation of an iconic butterfly 71–82Cornell University Press, (2015).

Dyer, L. A. & Letourneau, D. Top-down and bottom-up diversity cascades in detrital vs. living food webs. Ecol. Lett. 6, 60–68 (2002).

Robinson, S. K. & Holmes, R. T. Foraging behavior of forest birds: the relationships among search tactics, diet, and habitat structure. Ecology 63, 6 (1982).

Evens, R. et al. Proximity of breeding and foraging areas affects foraging effort of a crepuscular, insectivorous bird. Sci. Rep. 8, 3008 (2018).

Fuchs, T. W. & Harding, J. A. Seasonal abundance of arthropod predators in various habitats in the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Environ. Entomol. 5, 288–290 (1976).

Shapard, M., Carner, G. R. & Turnipseed, S. G. Seasonal abundance of predaceous arthropods in soybeans. Environ. Entomol. 3, 985–988 (1974).

Gauns, K. H., Tambe, A. B., Gaikwad, S. M. & Gade, R. S. Seasonal abundance of insect pests against forage Cowpea. Trends Biosci. 7, 1200–1204 (2014).

Eeva, T., Helle, S., Salminen, J. P. & Hakkarainen, H. Carotenoid composition of invertebrates consumed by two insectivorous bird species. J. Chem. Ecol. 36, 608–613 (2010).

Razeng, E. & Watson, D. M. Nutritional composition of the preferred prey of insectivorous 625 birds: popularity reflects quality. J. Avian Biol. 46, 89–96 (2014).

Brower, L. P. Avian predation on the monarch butterfly and its implications for mimicry theory. Am. Nat. 131, S4–S6 (1988).

Brower, L. P., Ryerson, W. N., Coppinger, L. L. & Glazier, S. C. Ecological chemistry and the palatability spectrum. Science 161, 1349–1351 (1968).

Brower, L. P., Brower, J. & Corvino, J. M. Plant poisons in terrestrial food chain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. (1967). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.57.4.893

Fink, L. S. & Brower, L. P. Birds can overcome cardenolide defense of monarch butterflies in Mexico. Nature 291, 67–70 (1981).

Olaya-Arenas, P. & Kaplan, I. Quantifying pesticide exposure risk for monarch caterpillars on milkweeds bordering agricultural land. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7 https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00223 (2019).

Wilson, J. S., Porter, T. & Carrill, O. M. Are vehicle strikes causing millions of bee deaths per day on Western united States roads? Preliminary data suggests the number is high. Sustainable Environ. 10 https://doi.org/10.1080/27658511.2024.2424064 (2024).

Davis, D. D. & Decoteau, D. R. A review: effect of Ozone on milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) in the USA and potential implications for monarch butterflies. J. Agricultural Environ. Sci. 7, 156–172 (2018).

Woodson, R. E. The North American species of. Asclepias L Annals Missouri Bot. Garden. 41, 1–211 (1954).

Martin, R. A., Lynch, S. P., Brower, L. P., Malcom, S. B. & Van Hook, T. Cardenolide content, emetic potency, and thin-layer chromatography profiles of monarch butterflies, Danaus plexippus, and their larval host-plant milkweed, Asclepias humistrata, in Florida. Chemoecology 3, 1–13 (1992).

Zust, T., Petschanka, G., Hastings, A. P. & Agrawal, A. A. Toxicity of milkweed leaves and latex: chromatographic quantification versus biological activity of cardenolides in 16 Asclepias species. J. Chem. Ecol. 45, 50–60 (2019).

Faldyn, M. J., Hunter, M. D. & Eldred, B. D. Climate change and an invasive, tropical milkweed: an ecological trap for monarch butterflies. Ecology 99, 1031–1038 (2018).

Fordyce, J. A. & Malcolm, S. B. Specialist weevil, Rhyssomatus lineaticollis, does not spatially avoid cardenolide defenses of common milkweed by ovipositing into pith tissue. Journal Chem. Ecology 26, (2000).

Vaughan, F. A. Effect of gross cardiac glycoside content of common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, on cardiac glycoside uptake by the milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus. J. Chem. Ecol. 5, 89–100 (1979).

Agrawal, A. A., Boroczky, K., Haribal, M. & Duplais, C. Cardenolides, toxicity, and the costs of sequestration in the coevolutionary interaction between monarchs and milkweeds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, 2024463118 (2021).

Nelson, C. J., Seiber, J. N. & Brower, L. P. Seasonal and intraplant variation of cardenolide content in the California milkweed, Asclepias eriocarpa, and implications for plant defense. J. Chem. Ecol. 7, 981–1010 (1981).

Zalucki, M. P., Brower, L. P. & Alonso, A. Detrimental effects of latex and cardiac glycosides on survival and growth of first-instar monarch butterfly larvae Danaus plexippus feeding on the sandhill milkweed Asclepias humistrata. Ecol. Entomol. 26, 212–224 (2001).

Baker, A. M., Redmond, C. T., Malcom, S. B. & Potter, D. A. Suitability of native milkweed (Asclepias) species versus cultivars for supporting monarch butterflies and bees in urban gardens. PeerJ 8 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9823 (2020).

USFWS & Monarch (Danaus plexippus) species status assessment report. (2020). https://www.fws.gov/media/monarch-butterfly-species-status-assessment-ssa-report

Statistix Analytical Software. Statistix 10 User’s Manual. (2013).

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank the Davey Tree Expert Company for funding this work and the lab personnel and colleagues at the Davey Institute that made it all possible: Carolyn Anderson, Ashley Kloes, Jenna Gooch, Alex Kramer, and Dr. AD Ali. I express tremendous gratitude to the individuals and entities that allowed me access to milkweed plantings in KY and OH: Lexington Parks and Recreation, Nancy Barnett, University of Kentucky, Janean and Denise Kazimir, Becca Zak, Chris Chaney, Joe Blanda, Dan Herms, Lara Rocketenetz, Rob Curtis, Summit Metro Parks, Bath Nature Preserve, and the University of Akron. I thank Dr. Thomas Whiteny for providing comments and review of previous versions of the manuscript. Lastly, I would also like to extend my appreciation for all of the family and friends that supported me throughout the duration of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.B. wrote the main manuscript text, analyzed the data, and prepared all figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, A.M. Assessing predation of monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) larvae using artificial caterpillar models. Sci Rep 15, 22147 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07516-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07516-2