Abstract

Lactococcus cremoris YRC3780, isolated from kefir, likely improves the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis response to acute psychological stress by acting on intestinal immune cells and promoting cytokine production. Here we examined the effectiveness of YRC3780 on the stress response in healthy Japanese adults. We investigated the effects of daily YRC3780 intake on the stress response in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group study of 107 healthy Japanese adults (54 in the YRC3780 group and 53 in the placebo group) who had an initial positive Uchida-Kraepelin (U-K) test stress response. After 8 weeks, the POMS2 Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) score after the U-K test and the change in score from baseline score were significantly better in the YRC3780 group than in the placebo. The YRC3780 group showed significant improvements in the POMS2 TMD and in five POMS2 subscores difference before and after the U-K test at 8 weeks. Daily YRC3780 intake significantly improved the stress response in healthy Japanese adults who had an initial stress response in the U-K test.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today’s society is considered stressful, and 82.2% of Japanese workers feel that there are things related to their current work or work life that cause them strong anxiety or stress (Reiwa 4 Occupational Safety and Health Survey1). The stress response is a natural adaptive response to external changes, but whether or not it is strong varies among individuals. If excessive stress persists, it can affect mental and physical health; because stress is difficult to eliminate, it is important for us to know how to deal with it and to thus reduce the risk of disease. As a coping strategy, it is important for us to understand the stresses we are subjected to, to relieve or reduce that stress in moderation, and to accelerate our recovery from the stress response.

Reports addressing the benefits of probiotic intake on the stress response are increasing. These benefits are assumed to occur through gut–brain interaction; signaling molecules from the gut to the brain include short-chain fatty acids (e.g., butyric acid) produced by intestinal bacteria, serotonin released from chromaffin cells in the small intestine, and cytokines produced by immune cells2,3,4. In particular, Lactococcus cremoris YRC3780 (hereafter, “YRC3780”), which is isolated from kefir, significantly increases IL-2 production by, and natural killer cell activity in, the spleens of colon-cancer-bearing mice5. In addition, YRC3780 consumption has alleviated the symptoms of birch pollinosis6 and perennial allergic rhinitis7 in healthy human adults, with decreased TARC (thymus and activation-regulated chemokine) production and a trend toward enhanced blood interferon-gamma levels7. Therefore, YRC3780 may act on immune cells in the intestinal tract to enhance cytokine production, and these cytokines in turn may improve the stress response.

A study of men in their 20 s confirmed that ingestion of YRC3780 for 8 weeks changed diurnal fluctuations in salivary cortisol, improved subjective sleep quality, and improved mental health. In addition, in a Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) conducted at 8 weeks as part of the study, salivary cortisol remained low in the YRC3780 group, and cortisol levels 40 min after the start of the test were significantly lower than those in the placebo group8. The stress response during the TSST (elevated cortisol concentration = hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal stress response) is affected by age, sex, and (in women) the menstrual cycle9,10,11,12.

A study of women reported that the stress response was observed only in the follicular phase and that the response was weaker in the luteal phase13. Moreover, in support of this finding, a trial that examined the difference in within-test reactivity between morning and evening TSSTs confirmed that reactivity in women did not differ from that in men when the TSST was administered in the follicular phase12. In the earlier TSST study8, it was considered difficult to adjust the timing of the TSST to each subject’s menstrual cycle, so the trial was conducted only in men and only in a group in their 20s.

In this study, we expanded the range of age and gender of the subjects, used the U-K test, which is easy to accomodate to in a wide range of age groups, rather than TSST. As an objective measure, we used salivary cortisol, which was conducted in previous studies. In addition, we also used the Profile of Mood States (POMS) as a subjective measure.

Results

Participants

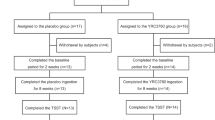

The 112 participants who met the eligibility criteria were enrolled in the study and assigned to receive either YRC3780 or the placebo (n = 56 per group). All participants received the allocated intervention, but 4 participants have not received any intervention after allocation. Therefore 4 participants were excluded from the analysis, for a final count of 108 participants (55 in the YRC3780 group and 53 in the placebo group) constituted the full analysis set (FAS2) and safety analysis set (SAF1). In addition, 1 participants was not undergo the post 8 weeks and therefore was excluded from the analysis for FAS2, for 107 participants (54 in the YRC3780 group and 53 in the placebo group) constituted the full analysis set (FAS1) and safety analysis set (SAF2). Figure 1 shows the participant flow throughout the study; Table 1 summarizes the backgrounds of the participants and their test meal consumption rates.

POMS2

The primary efficacy outcome—the POMS2 TMD score after the U-K test at 8 weeks—and the change in score from baseline were significantly lower in the YRC3780 group than in the placebo group (Table 2). This was also the case for the POMS2 subscore (AH, CB, DD, FI, TA) difference before and after the U-K test at 8 weeks and the change in score from the baseline were significantly lower in the YRC3780 group than in the placebo group (Table 3). Moreover, POMS 2 subscore (DD, TA), percentage change from baseline were significantly lower in the YRC3780 group than in the placebo group (Table 3). POMS TMD and subscore(AH, CB, DD, FI, TA) during intake period were shown in Table 4.

Salivary cortisol

Salivary cortisol levels before, after, difference before and after, the U-K tests at baseline and 8 weeks, and its change from baseline, did not differ significantly between the YRC3780 and placebo groups (Table S4).

VAS

VAS score for fatigue after, difference before and after the U-K tests at baseline and at 8 weeks, and its change from baseline, did not differ significantly between the YRC3780 and placebo groups (Table 5).

DASS-21

The DASS-21 scores at baseline, 4 weeks and 8 weeks, and its change from baseline, did not differ significantly between the YRC3780 and placebo groups (Table S5). Subjects who had been examined up to the 4 weeks were added to the baseline and 4 weeks analyses.

GHQ-28

The changes in the GHQ-28 scores at baseline, 4 weeks and 8 weeks, and its change from baseline, did not differ significantly between the YRC3780 and placebo groups (Table S6). Subjects who had been examined up to the 4 weeks were added to the baseline and 4 weeks analyses.

BDI-2

The BDI-2 scores at baseline, 4 weeks and 8 weeks, and its change from baseline, did not differ significantly between the YRC3780 and placebo groups (Table S7). Subjects who had been examined up to the 4 weeks were added to the baseline and 4 weeks analyses.

Discussion

The standardized (T) score used to evaluate POMS2 is a value that normalizes the metric; it has a mean value of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. The lower the T scores of TMD, TA, DD, AH, CB, and FI, which evaluate negative mood states, the more positive the mood state. In the case of VA and F, the higher the T score, the better the condition14. The primary outcomes, measured value of Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) in POMS2 after psychological stress load at 8 weeks, showed significantly lower values and changes in YRC3780 group compared to the placebo group (Table 1). In addition, regarding the other scores of POMS2 (TA, DD, AH, CB, and FI), YRC3780 group showed significantly lower values when compared to the placebo group (Table 2). Before and after the U-K test, the POMS subscores AH, CB, DD, FI, and TA decreased by an average of −0.2 to −1.9 (Table 3). The decrease in these scores may seems to that the U-K test contributes to mood states better. On the other hand, a study on the stress reduction effect of sniffing fragrances before the U-K test showed that even the control group aroma of water had a similar decrease of AH and DD by more than −1.0 before and after the U-K test. Furthermore, regarding CB, the control group increasing score, while the aroma group had a slightly decreasing score, indicating a significant difference. The above study anticipates an immediate relaxation effect from smelling fragrances, but such an effect is not expected in this research. Further studies are required to confirm reproducibility and to measure stress levels 30 min after the U-K test, comparing them to stress levels immediately afterward.

In previous study, it was confirmed that YRC3780 intake group, the salivary cortisol level 40 min after the TSST significantly decreased compared to the placebo group8. YRC3780 regulate the Th1/Th2 balance and induction of regulatory T cell15.In addition, a study by Slavich et al. in healthy adult men and women confirmed a significant increase in saliva IL-6 concentrations after the TSST16. It has also been reported that regulatory T cells decrease under acute stress loads such as the TSST and U-K test17. IL-6 is produced by Type 2 helper T cells (Th2 cells)18, but a previous study using a mouse model of atopic dermatitis confirmed that YRC3780 significantly reduced the concentration of IL-4 which is a marker of Th2 cells—in spleen cells, suggesting that it suppresses the activity of Th2 cells19. From these findings, it was inferred that YRC3780 reduced acute stress load through Treg induction and IL-6 suppression via the U-K test.

There were no significant differences between salivary cortisol,the VAS assessing fatigue,DASS-21 and BDI-2 which primarily assessed depressive symptoms. In previous studies, it was found that salivary cortisol levels increased due to TSST load, and in the YRC3780 group, the salivary cortisol levels at 40 min after the start of TSST significantly decreased compared to the placebo group. However, in this study salivary cortisol levels did not increase after the U-K test. There are reports indicating that the relationship between the U-K test load and cortisol in saliva did not change, similar to this study20, as well as reports that indicated an increase21, and no consistent conclusions have been reached. On the other hand, regarding reaction time to stress load, there are reports that amylase reacts quickly within 1 to several minutes22, whereas cortisol has a relatively long response latency of 20 to 30 min to stressors21,23. Shimizu et al. cortisol levels had already increased immediately after the U-K test compared to before the U-K test, but the peak occurred 20 to 30 min after the U-K test ended. Therefore, further research is needed. By increasing the number of saliva samples taken and measuring up to 30 min after the stress load, insights may be gained regarding the differences in reactivity between the TSST and U-K tests.

There are reports indicating that the fatigue VAS and POMS-2 FI show a good correlation24. However, Izawa et al. although there was no significant difference in FI in POMS-2, the mean values differed by more than 1.0, while the Average VAS scores were 39.2 and 39.7 without significant difference. Additionally, while VAS is a measure of fatigue, FI in POMS-2 differs in that it includes not only fatigue but also worn out, exhausted, weary and bushed. Therefore, while the tendency to shift negatively under stress is consistent, it is highly likely that the outcomes will not be the same.

In a study of American college men and women, individual differences in anxiety sensitivity were significantly correlated with the POMS2 TA score during stress loading, but no correlations were found with individual differences in anxiety traits25. In addition, the neural circuits that control anxiety and stress overlap, suggesting that there is a strong bidirectional relationship26. Our participants were selected to have relatively high TMD scores on POMS2 after U-K test at baseline, taking into account stress sensitivity, but not personality traits.

The Depression (D) subscale of POMS2 has been reported to be correlated with the total BDI-2 score27,28. Examination of the T scores for DD before stress load in our participants revealed that the mean score (estimated peripheral mean) and median score remained at about 50 points throughout the study period; as this value is considered to be average14, we inferred that the degree of depression was also average. In addition, over a time frame of more than 1 week, it is likely that the mood state specific to the situation at that time and the characteristics of that mood state will be mixed14,29. Whereas POMS2 has been shown to be useful over various time frames14, the DASS-21 questionnaire asks about a person’s state over the past week, so the influence of individual personality traits on the results of DASS-21 cannot be ruled out. Therefore, the lack of between- group significant differences in both DASS-21 and BDI-2, which were assessed only before the stress loading, may have been influenced by the personality traits of the trial participants.

Finally, our safety evaluations identified no adverse events in any of the participants throughout the study. Among those cases in which urinalysis and peripheral blood test measurements that were within the reference ranges at baseline fluctuated outside the reference ranges after the intervention, there were also some other items that were outside the reference values during the study period. However, for each group and item, the principal investigator confirmed that no medically problematic changes occurred upon consumption of the test meals (YRC3780 or placebo). Therefore, consumption of the test meals under the conditions of this study was safe.

The limitations of our study are that several cytokines including IL-6 were not measured, and that salivary cortisol, POMS2 and VAS for fatigue were only meseaed until immediately after U-K test. Further study is needed to explore the anti-stress and anti-fatigue effects of YRC3780, these parameters meseaed from 0 to 30 min after the U-K test.

This study found that daily intake of YRC3780 improves the stress response in healthy adults with a positive stress response in the U-K test.

Methods

Participants

Study participants were healthy Japanese adult men and women with increased POMS2 TMD scores after the U-K test at baseline and did not meet any of the exclusion criteria (Table 6). We enrolled 112 participants meeting these criteria and randomized two groups according to a computer-generated allocation table by the allocation officer. The allocation list was sealed in an envelope that was stored until the completion of data collection. The allocation was performed by allocation officer and concealed from the subjects, physicians, and researchers who recruited and assessed the participating subjects.

By using a document prepared by the study investigators, the study management staff of Orthomedico Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) explained the study to potential participants and, after confirming their full comprehension, obtained their voluntary informed consent to participate.

Sample size

There has been no study to date that evaluates the impact of this test food on stress in healthy individuals based on the measured values of TMD after consumption for 8 weeks. Therefore, this study assumes that the difference in the measured values of TMD after the challenge between the test food group and the placebo group at the visit after 8 weeks of consumption is large, using Cohen’s suggestion of d = 0.80. The statistical significance level (α) was set at 0.05, and the statistical power (1 − β) was set at 0.90, calculating a required sample size of 68 participants (34 in each group). The target sample size was set at 100 participants (50 in each group). Additionally, to account for dropout and protocol violations during the trial period, the number of participants implemented was set to 112 (56 in each group).

Test meal

The test meal was a capsule containing at least 5.9 × 1010 YRC3780 cells, cellulose, starch, and potassium stearate; placebo capsules did not contain YRC3780 but were otherwise the same. Both types of capsule were brown, thus preventing identification of the contents. The total cell count of YRC3780 in the test meal was confirmed by using a blood cell counter before the start of the study and through 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining and quantitative PCR analysis at the end of the study.

DNA extraction and PCR protocols

DNA extraction from the test meal was performed by using a Food DNA Isolation Kit (Norgen Biotek, Thorold, Canada) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR analysis was performed by using the L. cremoris subsp. cremoris – specific primer LcCr-F, which was designed to target the 16S rRNA gene; the primer Lc-R, which detects most Lactococcus species30; and the LNA (locked nucleic acid) probe new-24base-LNA*3, to distinguish L. cremoris subsp. cremoris from the closely related species L. cremoris subsp. tructae (FASMAC, Kanagawa, Japan) (Table S1). Reaction mixture components and PCR condition were following at Table S2, S3.

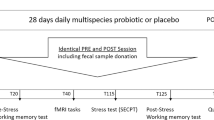

Study design

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial was conducted from February through April 2024 in Japan. The 112 participants were assigned to either the YRC3780 group (n = 56) or the placebo group (n = 56). The participants were instructed to swallow one capsule (test meal or placebo) once daily for 8 weeks.

To evaluate subjective stress responses, before and after the U-K tests (baseline and 8 weeks) each participant completed the POMS2 test and had their salivary cortisol level measured. To evaluate fatigue, each participant completed a visual analog scale (VAS) before and after the U-K tests (baseline and 8 weeks). To evaluate normal mental status, each participant completed the BDI-II Beck Depression Questionnaire (BDI-2), the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 Items (DASS)−21, and the General Health Questionnaire – 28 Questions (GHQ-28) throughout the study (at baseline and at 4 and 8 weeks).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (revised version, 2013) and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects as stipulated by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology; the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; and the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry of Japan. It was approved by the institutional ethical review board at Seishinkai Medical Association Inc., Takara Clinic, on 18 October 2023. The study was registered in the University Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry (trial UMIN000052605. 25/10/2023).

Efficacy outcomes and methods

The primary efficacy outcome was the POMS2 total mood disturbance (TMD) score after the U-K test at 8 weeks. The TMD score is calculated by adding the Tension-Anxiety (TA), Depression-Dejection (DD), Anger-Hostility (AH), Confusion-Bewilderment (CB), Anger-Hostility (AH), and Fatigue-Inertia (FI) subscores and then subtracting the Vigor-Activity (VA) subscore. The seven secondary outcomes were: a. the change in the POMS TMD score after the U-K test at 8 weeks from baseline and this percentage change; b. the POMS TMD score difference before and after the U-K test at 8 weeks, the change in score from the baseline, and percentage change from baseline; c. the POMS TMD score before the U-K test at 8 weeks, the change in score from the baseline, and percentage change from baseline; d. POMS2 (TA, DD, AH, CB, VA, FI, F) subscores, the VAS score for fatigue, salivary cortisol levels, after the U-K test at 8 weeks and difference before and after the U-K test at 8 weeks, the change in score from the baseline, and percentage change from baseline; e. POMS2 (TA, DD, AH, CB, VA, FI, F) subscores, the VAS score for fatigue, salivary cortisol levels, before the U-K test at 8 weeks, the change in score from the baseline, and percentage change from baseline; f. the DASS-21 scores for depression, anxiety, and stress, the GHQ-28 total score and the physical symptoms (A scale), anxiety and insomnia (B scale), social activity disorder (C scale), and depressive tendency (D scale) subscores, and the BDI-2 total score at 8 weeks, the change in score from the baseline, and percentage change from baseline; g. the POMS2 (TMD, TA, DD, AH, CB, VA, FI, and F), the VAS for fatigue score, the DASS-21 depression, anxiety and stress score, the GHQ-28 total score and physical symptoms (A scale), anxiety and insomnia (B scale), social activity disorder (C scale), and depressive tendency (D scale) subscores, and the BDI-2 total score at 4 weeks, the change in score from the baseline, and percentage change from baseline.

Safety outcomes and methods

The primary safety outcome was the occurrence of adverse events. The secondary safety outcomes were the proportions of cases in which urinalysis and peripheral blood test results that were within the reference ranges at baseline exceeded them at 8 weeks. Other safety outcomes included physical measurements, physical examination data, and the results of urinalysis and peripheral blood tests.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted by using IBM SPSS statistics software, version 23 and higher (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was designed to focus on the primary outcome and did not consider multiplicity occurring in the secondary outcomes, which were set up in a multihypothetical manner.For efficacy outcomes, differences between groups were evaluated by using Welch’s t-test and ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) with baseline values as covariates, as appropriate, with results reported as means ± standard deviation. The data set analyzed for efficacy outcomes was the full analysis set.

For the primary safety outcome, adverse events were tabulated by participant; incidence rates for adverse events were tabulated by group, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the incidence rates by group and for the difference in incidence rates between groups. The incidence of adverse events was compared between groups by using the chi-square test. For the secondary safety outcomes, we used the chi-square test to calculate the proportion of cases in which the urinalysis and peripheral blood test results that were within the reference values at baseline exceeded those limits afterward and to compare these data between groups by time point. For the other safety outcomes, summary statistics were calculated for each laboratory value. The data set analyzed for safety outcomes was the safety analysis population.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Reiwa 4 Occupational Safety and Health Survey https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/dl/r04-46-50_gaikyo.pdf.

Cryan, J. F. & Dinan, T. G. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13(10), 701–712 (2012).

Kim, Y. K. & Maes, M. The role of the cytokine network in psychological stress. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 15(3), 148–155 (2003).

Montiel-Castro, A. J., González-Cervantes, R. M., Bravo-Ruiseco, G. & Pacheco-López, G. The microbiota-gut-brain axis: Neurobehavioral correlates, health and sociality. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 7, 70 (2013).

Motoshima, H., Uchida, K., Watanabe, T., Tsukasaki F. Immunopotentiating effects of kefir and kefir isolates in mice. In Proceedings of the 26th International Dairy Congress, the 26th IDF World Dairy Congress. (Paris, Arilait Recherches, 2002).

Uchida, K. et al. Effect of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris YRC3780 on birch pollinosis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Funct. Food. 43, 173–179 (2018).

Uchida, K. et al. Effect of drinkable yogurt containing Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris YRC3780 on symptoms of perennial allergic rhinitis ―a randomized, double‒blind, placebo‒controlled, parallel-group comparison study. Jpn. Pharmacol. Ther. 49(7), 1165–1174 (2021).

Matsuura, N., Motoshima, H., Uchida, K. & Yamanaka, Y. Effects of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris YRC3780 daily intake on the HPA axis response to acute psychological stress in healthy. Jpn. men. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 76(4), 574–580 (2022).

Godoy, L. D., Rossignoli, M. T., Delfino-Pereira, P., Garcia-Cairasco, N. & de Lima Umeoka, E. H. A Comprehensive overview on stress neurobiology: Basic concepts and clinical implications. Front. Behav. Neurosis. 12, 127 (2018).

Kirshbaum, C., Pirke, K. M. & Hellhammer, D. H. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28, 76–81 (1993).

Kudielka, B. M., Schommer, N. C., Hellhammer, D. H. & Kirschbaum, C. Acute HPA axis responses, heart rate, and mood changes to psychosocial stress (TSST) in humans at different times of day. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29, 983–992 (2004).

Yamanaka, Y., Motoshima, H. & Uchida, K. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis differentially responses to morning and evening psychological stress in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 39(1), 41–47 (2019).

Maki, P. M. et al. Menstrual cycle effects on cortisol responsivity and emotional retrieval following a psychosocial stressor. Horm. Behav. 74, 201–208 (2015).

Yokoyama, K. Japanese Manual of Profile of Mood States. In 2nd eds. (Kaneko Shobo, 2015).

Nakagawa, R. et al. Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris YRC3780 modified function of mesenteric lymph node dendritic cells to modulate the balance of T cell differentiation inducing regulatory T cells. Front. Immunol. 8(15), 1395380 (2024).

Slavich, G. M. et al. Neural sensitivity to social rejection is associated with inflammatory responses to social stress. PNAS 107(33), 14817–14822 (2010).

Freier, E. et al. Decrease of CD4 + FOXP3+ T regulatory cells in the peripheral blood of human subjects under going a mental stressor. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 663–673 (2010).

Kubo, M. Regulation of Th2 development and IgE antibody production. Allergy 62(11), 1443–1450 (2013).

Wang, D. et al. The effect of sleep duration and sleep quality on hypertension in middle-aged and older Chinese: The dongfeng-tongji cohort study. Sleep Med. 40, 78–83 (2017).

Izawa, N. et al. Stress reduction effect of aroma of whey fermented liquid. J. Soc. Cosmer. Chem. Jpn. 55(2), 162–168 (2021).

Shimizu, M., Higuchi, T., Kawakami, Y., Shimomura, H. & Shiba, K. Changes in salivary protein levels depending on the stress load. J. Anal. Bio.-Sci. 38(3), 173–180 (2015).

Takai, N. et al. Effect of psychological stress on the salivary cortisol and amylase levels in healthy young adults. Arch. Oral Biol. 49(12), 963–968 (2004).

Kudielka, B. M., Buske-Kirschbaum, A., Hellhammer, D. H. & Kirschbaum, C. HPA axis responses to laboratory psychosocial stress in healthy elderly adults, younger adults, and children: Impact of age and gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29(1), 83–98 (2004).

Kobayashi, M., Hoshi, N. & Horiguchi, M. Validity of self-diagnosis fatigue checklist for young women. Int. J. Hum. Cult. Stud. 29, 526–536 (2019).

Shostak, B. B. & Peterson, R. A. Effects of anxiety sensitivity on emotional response to a stress task. Behav. Res. Ther. 28(6), 513–521 (1990).

Daviu, N. et al. Neurobiological links between stress and anxiety. Neurobiol. Stress. 11, 1–9 (2019).

Griffith, N. M. et al. Measuring depressive symptoms among treatment-resistant seizure disorder patients: POMS Depression scale as an alternative to the BDI-II. Epilepsy Behav. 7(2), 266–272 (2005).

Wang, Y.-P. & Gorenstein, C. Assessment of depression in medical patients: A systematic review of the utility of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Clinics 68(9), 1274–1287 (2013).

Rosenberg, E. L. Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2(3), 247–270 (1998).

Odamaki, T. et al. Novel multiplex polymerase chain reaction primer set for identification of Lactococcus species. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 52, 491–496 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the study participants. We also thank the staff of FASMAC (Kanagawa, Japan) for designing the LNA probe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KU was responsible for project administration, supervision, investigation, and data curation and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. IF conducted project administration, investigation, and data curation and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the institutional ethical review board at Seishinkai Medical Association Inc., Takara Clinic, on 18 October 2023. It was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki (revised version of 2013) and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects as stipulated by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology; the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; and the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry of Japan.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fujioka, I., Uchida, K. Lactococcus cremoris YRC3780 improves subjective stress response in the Uchida-Kraepelin test: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Sci Rep 15, 23393 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07783-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07783-z