Abstract

Helicases and endonucleases play crucial roles in genome maintenance by unwinding or cleaving various forms of DNA and RNA structures in order to facilitate essential biological processes, such as DNA replication and recombination. Here, we identified fission yeast Dbl2 as a potential interactor of several complexes that exhibit either helicase or endonuclease activity, namely Fml1-MHF, SCFFbh1, Rqh1-Top3-Rmi1, and Mus81-Eme1. In vitro, Dbl2 binds to DNA, with a preference for branched molecules, such as D-loops, mobile Holliday junctions, and fork structures, making it a good candidate to play a central role in modulating the activity of helicases and endonucleases during replication and recombination repair. Previously, we showed that Dbl2 recruits Fbh1 to the ongoing homologous recombination sites, affecting the Rad51-nucleofilament. In this study, we determined that deleting dbl2 in an fbh1Δ background did not increase sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents or the frequency of Tf2 ectopic recombination. Therefore, Dbl2 and Fbh1 might be involved in the same molecular pathway, maintaining genome integrity by hindering ectopic recombination at repetitive elements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In eukaryotes, homologous recombination (HR) plays an essential role in generating genetic diversity during meiosis. In vegetative cells, HR is a fundamental process involved in preserving genetic information by facilitating the repair of DNA damage, such as double-strand breaks (DSBs) or the collapse of replication forks (RFs). Failure to repair DSBs or properly restart stalled and collapsed replication forks can lead to genomic instability, chromosomal aberrations and an increased risk of cancer.

HR begins with the resection of the DNA ends to produce recombinogenic DNA with 3’ single-strand overhangs. Rad51 recombinase binds the resulting single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) to form a nucleoprotein filament that catalyzes a strand-exchange reaction between the broken end and the homologous sequence, forming a D-loop structure. Several accessory proteins, including fission yeasts Rad52, Rad55, Rad57, Swi5, and Sfr1, have been shown to form and activate the presynaptic filament of Rad51 recombinase1. Furthermore, Rad51-mediated HR is regulated by several DNA helicases, namely, Fbh1, Fml1, Srs2, and Rqh1. These helicases can disrupt DNA structures, such as D-loops, and displace proteins bound to DNA2,3. A key function of these helicases is to counteract recombination, particularly at collapsed or stalled replication forks, where excessive recombination can lead to genomic instability. By limiting inappropriate recombination events, these enzymes help to maintain genome integrity and prevent deleterious chromosomal rearrangements.

The essential role of helicases in maintaining genome stability is evident by their involvement in various genetic disorders and chromosomal instability diseases. For instance, mutations in genes encoding helicases BLM, WRN, RECQ4, and FANCM are clinically associated with Bloom syndrome, Werner syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, and Fanconi anemia disorder, respectively4. Similarly, as in mammalian cells, mutational inactivation of helicases Fbh1, Rqh1, or Fml1 in S. pombe leads to elevated levels of HR and chromosomal instability5,6,7,8,9. Therefore, studies performed in eukaryotic model organisms such as yeast provide information relevant to understanding molecular mechanisms underlying human diseases.

Each helicase and endonuclease has evolved to recognize and act on specific types of DNA damage or distinct DNA structures. Although one helicase/endonuclease may partially compensate for the loss of other helicase/endonuclease, such substitution may lead to the accumulation of toxic recombination intermediates. A deeper understanding of the involvement of specific helicases in different steps of recombination processes will require further investigation.

The specific function of S. pombe helicases, endonucleases, and their interacting proteins in HR can be summarized as follows.

The Fbh1 helicase inhibits Rad51-driven DNA strand exchange by removing Rad51 from the nucleofilament10. Fbh1 interacts with Skp1 and Cullin 1 to form the SCFFbh1 complex, which can ubiquitinate Rad51, thereby marking it for degradation. However, it has been suggested that Fbh1 might also have a pro-recombination role10.

The Fml1 helicase and its orthologs (Mph1 in S. cerevisiae) possess the ability to process recombination intermediates through DNA branch migration11,12,13. They catalyze the dissociation of D-loops to promote DSB repair by synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA)14,15,16,17,18. Fml1 interacts with the centromeric proteins Mhf1 and Mhf2, which form a complex that binds DNA and modulates Fml1 stability and activity19,20,21,22,23.

The RecQ family helicases, which include fission yeast Rqh1, human BLM, and budding yeast Sgs1, play a role in both the early and late steps of HR. Sgs1 is required for the long-range resection of DSBs, D-loop disassembly, Rad51 removal, double-Holliday junction (dHJ) dissolution, and the prevention of the accumulation of complex and aberrant joint molecules engaging multiple chromatids24,25,26. It has also been proposed that S. pombe Rqh1 is involved in the early and late steps of HR. However, in vitro studies showing that Rqh1 can process recombination intermediates like Sgs1 have yet to be performed27. In vitro, the activity of Sgs1 and BLM is markedly stimulated by the presence of their interaction partners Rmi1/RMI1 and Top3/TOP3α28,29. Notably, some activities of the Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 complex (STR), such as nascent D-loop disruption, are topoisomerase-dependent and helicase-independent30,31.

Moreover, nucleases, such as Mus81-Eme1, are also essential for resolving recombination intermediates that escape the helicase action32,33. Mus81-Eme1 can efficiently cleave various structures, including 3′ flaps, D-loops, and nicked HJs34,35,36.

The roles of helicases and endonucleases are also crucial for maintaining RF stability. One of the major challenges during replication is when the RF encounters barriers, such as DNA lesions or tightly bound proteins. DNA helicases can remove or bypass these replication barriers or remodel the replication fork into a HJ-like structure through a process called RF reversal. This mechanism helps protect the fork from collapse, giving the cell time to resolve the problem and restart the RF.

Studies with human proteins have shown that fork reversal requires helicases, such as FBH1 and the RecQ family enzymes – WRN, BLM, and RecQ537,38,39,40,41. Two other families of proteins capable of fork reversal include the SWI/SNF and FANCM enzymes. In S. pombe, Fml1 has been shown to catalyze fork reversal and the restoration of regressed forks9,17. In addition to helicases, Mus81-Eme1 can cleave stalled replication forks to initiate HR-mediated fork repair42.

In our previous study, we identified Dbl2 as a novel regulator of Rad51-mediated DSB repair in S. pombe43. Our results showed that Dbl2 is required for the formation of Fbh1 foci at sites of DNA lesions, thereby facilitating the timely removal of Rad51 recombinase. The Dbl2 protein contains the DUF2439 domain, which is shared with the budding yeast Mte1 and the human ZGRF1 protein. Several data indicate that these proteins might be functionally related. Mte1 has been recently identified as a novel subunit of the Mph1-MHF complex (Fml1-MHF in S. pombe)44,45,46. It interacts with Mph1 and regulates its activities in multiple ways – it stimulates the RF regression and branch migration and inhibits D-loop dissociation44,45,46. Interestingly, ZGRF1 contains 5’-to-3’ helicase activity with the ability to remodel DNA molecules47. The ZGRF1 protein is recruited to replication-blocking DNA lesions, where it interacts with the RAD51 protein and stimulates strand exchange catalyzed by RAD51-RAD54 during recombinational repair47.

As described above, significant progress has been made in understanding the function of helicases and endonucleases. However, the roles of associated proteins that modulate their localization and activities still need to be better understood. Here, using mass spectrometry and yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay, we characterized the interacting partners of the S. pombe Dbl2 protein. We report that Dbl2 physically interacts with a subunit of the Mus81-Eme1 endonuclease and three helicase-containing complexes, namely Fml1-MHF (Fml1-Mhf1-Mhf2), SCFFbh1 (Fbh1-Cullin 1-Skp1), and RTR (Rqh1-Top3-Rmi1). In vitro, Dbl2 might bind preferentially to branched DNA molecules, such as D-loops, mobile HJs, and fork structures. Additionally, we found that Dbl2 interacts with itself, making it a good candidate for serving as an organizing centre. Epistasis analysis showed positive genetic interactions between dbl2Δ and fbh1Δ and negative genetic interactions between dbl2Δ and fml1Δ, as well as between dbl2Δ and eme1Δ. Interestingly, dbl2Δ cells contained deletions within rDNA regions, a significant increase in Tf2 ectopic recombination, and an overrepresentation of loops within the chromosomes and at their ends, consistent with the notion that Dbl2 prevents unwanted recombination. Overall, our results implicate Dbl2 as an important regulator of HR.

Results

Dbl2 associates with subunits of three helicase-containing complexes: Fml1-MHF, SCFFbh1, and RTR, as well as with the Mus81 subunit of the structure-specific endonuclease Mus81-Eme1.

We have previously shown that the Dbl2 protein is required in the fission yeast for the nuclear foci formation of the Fbh1 helicase43. To further characterize the function of Dbl2 in its cellular context, we performed a tandem affinity purification (TAP) of the Dbl2-TAP tagged strain and identified the interacting proteins by mass spectrometry (MS) (Fig. 1A, S1, and Table S4)48,49.

Dbl2 is associated with DNA repair proteins. (A) List of selected proteins with determined label-free quantification (LFQ) intensities (see Material and Methods) co-purified with Dbl2-TAP. Proteins associated with Dbl2 were isolated from cycling S. pombe cells (strain SP1210) by tandem affinity purification and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Results of three independent experiments are shown (Dbl2_S1, Dbl2_S2, Dbl2_S3). Proteins of higher abundance are indicated by red color, while proteins of lower abundance are indicated by green color. For a complete list of co-purified proteins and their post-translational modifications, see Table S4. (B, C, D) S. cerevisiae strains (SP1, Table S1) expressing Dbl2 fused to the GAL4 transcription activation domain (AD) and Fml1, Mhf1, Mus81, Rmi1, or Dbl2 fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (BD) were grown on SD plates lacking Leu and Trp (SD-LW) and then spotted at tenfold serial dilutions on SD-LW or SD plates lacking Leu, Trp, and His (SD-LWH) or SD plates lacking Leu, Trp, and Ade (SD-LWA). The empty vectors pGADT7 and pGBKT7 containing AD and BD, respectively, were used as negative controls. Growth on plates without His or Ade indicates interaction between the fusion proteins. In cases where the strains did not grow on plates without Ade, those plates are not shown.

We found that the helicase Fml1, and the centromeric proteins Mhf1 and Mhf2, also known as CENP-S and CENP-X, co-purified with Dbl2. This result is consistent with the findings that the S. cerevisiae homolog of Dbl2, Mte1, exists in the complex with Mph1-MHF in the budding yeast44,45. We found that the Dbl2 protein is also associated with the Fbh1 helicase and the Skp1 protein, which are part of the evolutionarily conserved SCFFbh1 complex10. Furthermore, other DNA repair proteins, namely the single-strand DNA-binding protein Ssb1 (a subunit of Replication Protein A/RPA), DNA damage checkpoint protein Rad24, and both subunits of the Ku70/Ku80 complex, which bind to a large variety of DNA ends, were enriched in Dbl2-TAP purifications. The Hob1 protein, previously demonstrated to interact with Ku proteins50, was also identified in our purifications. Other co-purifying factors included all of the histone core proteins H4, H3, H2B, H2A, and H2A variant H2A.Z, encoded by hhf1, hht1/hht3, htb1, hta1, and pht1, respectively, and histone H2A-H2B chaperone Nap1. Notably, NAP1 family histone chaperones are known to be required for somatic HR in Arabidopsis thaliana51.

To further analyze the protein–protein interactions between Dbl2 and the top proteins identified in the Dbl2-TAP purifications, we performed a Y2H analysis. We tested for interactions between Dbl2 and the three known subunits of the Fml1-MHF complex and between Dbl2 and the two subunits of the SCFFbh1 complex. The known positive interactions between Fml1 and Dbl2 were used as a control43. We found that Dbl2 weakly interacts with Mhf1 (Fig. 1B). The direct interactions of Dbl2 with both Fml1 and Mhf1 suggest that Dbl2 could represent another subunit of the Fml1-MHF complex. However, we could not detect direct interactions between Dbl2 and subunits of the SCFFbh1 complex (Fig. S2, Table S5)43. This lack of Y2H interactions could be due to an indirect interaction that requires additional proteins for their association or the loss of protein interaction capacity in the Y2H assay. Notably, our mass spectrometry analysis revealed that Dbl2 is phosphorylated at eleven amino acid residues when interacting with Fml1-MHF and SCFFbh1 or other DNA repair proteins: S310, S343, S471, T601, S603, S604, S606, T608, S610, S611, and S612 (Table S4, column Phospho (STY) site positions). Since these residues are located within a surface-exposed region of Dbl2, potentially involved in mediating protein–protein interactions, it is plausible that the absence of these phosphorylation events in the Y2H assay could prevent the detection of certain interactions. Therefore, further studies will be needed to better understand the functional significance of the detected phosphorylation in Dbl2, particularly in the regulation of its interactions. Additionally, interference from endogenous S. cerevisiae proteins may further disrupt or mask specific interactions involving Dbl2.

A notable number of proteins involved in DNA damage, uncovered in Dbl2-TAP purifications, prompted us to test other HR proteins in the Y2H assay. These include proteins involved in ssDNA binding (Ssb1, Ssb2, and Ssb3), DSB end resection (Ctp1, Mre11, Rad50, and Nbs1), Rad51 mediators (Rad52, Rad55/57, Sfr1, and Swi5), the Rad54 protein, subunits of the RTR complex, the Srs2 helicase, and the Mus81 endonuclease, which is essential for the disassembly of the recombination intermediates (Table S5). Previously, we showed that Dbl2 interacts with the Rad51 recombinase in the Y2H assay43. While we did not observe any interactions between Dbl2 and other mediator proteins, the Rad54 protein, ssDNA binding proteins, or proteins involved in DSB end resection, we observed interactions between Dbl2 and the Mus81 endonuclease, and between Dbl2 and the Rmi1 protein, which is part of the RTR complex28,29 (Fig. 1C). The negative results for other proteins do not rule out the possibility that they might be part of larger complexes.

Furthermore, our research has revealed that Dbl2 also binds to itself, as is evidenced by the improved growth of cells in the presence of both BD-Dbl2 and AD-Dbl2 fusions on plates lacking adenine (Fig. 1D). It has been previously shown that many HR proteins – Rad51, Rad52, and Rti1, for example – are able to self-interact and form oligomers52,53,54,55.

Overall, our results revealed new interacting proteins of Dbl2. Dbl2 is capable of association with itself, Mus81, and subunits of three conserved helicase complexes (Fml1-MHF, SCFFbh1, RTR). This suggests that Dbl2 may have the potential to modulate several sub-pathways of HR.

Dbl2 does not affect the localization of Mus81 and Rmi1

Our previous observation that Dbl2 promotes the formation of Fbh1 foci raised the possibility that Dbl2 could regulate the recruitment of different DNA repair factors to DNA lesions43. Interestingly, it has also been shown that in the absence of Dbl2, Fml1 foci become dramatically reduced at HO-induced DSBs56. To visualize Mus81 and Rmi1, which were also identified as interacting with Dbl2 physically, we overexpressed the respective fusion proteins with YFP or NeonGreen under the nmt promoter in wild-type and dbl2Δ strains (Fig. S3). Overexpression of Mus81-YFP produces a signal detectable within the nucleus and at the distal tips of cells, and overexpression of Rmi1-mNG leads to a signal distributed throughout the cells, with a higher intensity in the cell nucleus. In neither case did we observe nuclear foci. Nevertheless, we did not detect any significant difference in signal intensity or in the distribution of Mus81-YFP and Rmi1-mNG between wild-type and dbl2Δ cells, either under normal conditions or following exposure to the DNA-damaging agent CPT (Fig. S3).

The finding that Dbl2 is required for efficient Fbh1 and Fml1 foci formation led us to examine the Fbh1-TAP and Fml1-TAP protein levels in cells lacking Dbl2. The analysis of whole-cell extracts showed no difference in the level of Fbh1 and Fml1 between dbl2Δ and wild-type cells (Fig. S4). These data are consistent with previous observations that Dbl2 is required to recruit Fbh1 and Fml1 to DNA lesions and not for protein stability.

Since we did not observe the effect of Dbl2 in the localization of Mus81 and Rmi1, we next tested the formation of Dbl2-YFP foci in the absence of Fml1, Mus81-Eme1, or Rqh1, as the deletion of rmi1 or top3 is not viable. We previously showed that deletion of fbh1 does not impact the formation of Dbl2-YFP foci within the nucleus43. Because Dbl2-YFP signal is not visible when the tagged gene is expressed from its endogenous locus, we analyzed Dbl2-YFP overexpressed from the nmt promoter. Our analysis revealed a significant decrease in nuclei containing a Dbl2-YFP signal in fml1Δ, mus81Δ, and rqh1Δ cells (Fig. S5). These findings suggest that Fml1, Mus81, and Rqh1 may influence Dbl2 localization, possibly through their roles in replication fork processing or protein–protein interactions.

Deletion of dbl2 partially suppresses the hypersensitivity of fbh1Δ to DNA-damaging agents

Protein–protein interactions capture physical contacts between proteins but do not necessarily reflect the functional relationships between genes. To better understand the biological consequences of the identified protein–protein interactions within specific sub-pathways of DNA repair or replication fork stability, we examined the response to DNA-damaging agents in single and double mutants of dbl2Δ, combined with deletions of genes encoding proteins identified as primary interactors. Previously, we identified positive genetic interactions between dbl2Δ and mutations in HR-related genes such as rad52, rad55, rad57, sfr1, and rad5443. Furthermore, we observed a synthetic lethality of rqh1Δ with dbl2Δ, which was suppressed by the deletion of rad51 in mitotic cells43. Here, we tested mutants of dbl2Δ, in combination with fbh1Δ, fml1Δ, and eme1Δ (a subunit of Mus81-Eme1 endonuclease), under normal growth conditions and upon exposure to DNA-damaging agents such as the topoisomerase I poison camptothecin (CPT), the DNA alkylating agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), and hydroxyurea (HU). HU and MMS are believed to cause RF stalling, and the toxic effect of CPT results, mainly from RF collapse at single DNA ends.

In the case of Fbh1, the deletion of dbl2Δ rescued the CPT, MMS, and HU sensitivity of fbh1Δ to some extent (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the fml1Δ dbl2Δ double mutants were considerably more sensitive to CPT, MMS, and HU than single mutants (Fig. 2A). Likewise, the eme1Δ dbl2Δ double mutants exhibited a slightly increased sensitivity to all the mutagens used, in comparison to single mutants (Fig. 2A).

dbl2 shows positive genetic interactions with fbh1 and negative genetic interactions with fml1 and eme1 on plates containing CPT, MMS, or HU. (A) Wild-type (SP65) and mutant strains dbl2Δ (SP067), fbh1Δ (SP70), fbh1Δdbl2Δ (SP1392), dbl2Δ (SP1310), fml1Δ (SP1292), fml1Δdbl2Δ (SP1323), dbl2Δ (SP067), eme1Δ (SP1322), and eme1Δdbl2Δ (SP1280) were cultivated until reaching the exponential phase in YES medium. Tenfold serial dilutions of cell suspensions were spotted on the plates containing indicated amounts of CPT, MMS, and HU. Plates supplemented with DMSO were used as controls for plates with CPT. In general, images were taken after 3-day cultivation at 30 °C, but in the case of eme1Δdbl2Δ strains after 5-day cultivation. (B) Wild-type (SP65) and dbl2Δ strains (SP67) expressing either Fml1-YFP (p15), Mus81-YFP (p126), Rmi1-mNG (p230) or empty vectors (EV) (p227, p228) were grown in EMM2 liquid medium lacking thiamine and uracil for 18 h, diluted in tenfold steps, and spotted onto EMM2 plates lacking thiamine, uracil and containing the indicated amounts of CPT or MMS. Plates supplemented with DMSO were used as controls for plates with CPT. Images were taken after 3-day cultivation at 30 °C.

Analysis of gene overexpression provides complementary information to gene deletion effects and may be equally important for understanding the functional connections between genes57. We previously showed that the CPT sensitivity of dbl2Δ was nearly entirely suppressed by Fbh1-YFP overexpression, suggesting that Dbl2 exerts its function through Fbh143. In this study, we examined the effects of the overexpression of Fml1-YFP, Mus81-YFP, and Rmi1-mNG on the CPT and MMS sensitivity of wild-type and dbl2Δ mutant cells. All genes were overexpressed from a strong nmt1 promoter. It was previously reported that Rqh1 overexpression is lethal in wild-type cells, as it produces DNA structures that cells cannot resolve58. Overexpression of Fml1-YFP increased the CPT sensitivity of wild-type cells compared to the same strain carrying an empty vector (EV) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, these cells were less sensitive than wild-type cells with EV upon MMS exposure. These data indicate that different helicases may be effective at processing specific types of DNA lesions, and incorrect utilization of these helicases can lead to increased sensitivity of the cells. Interestingly, wild-type and dbl2Δ cells with overexpression of Fml1 exhibited similar sensitivities to both MMS and CPT, indicating that in the presence of excess Fml1, Dbl2 becomes redundant (Fig. 2B). Overexpression of Mus81-YFP and Rmi1-mNG did not have any significant effect on the MMS and CPT sensitivity of dbl2Δ compared to dbl2Δ cells carrying an EV (Fig. 2B).

These data suggest that Dbl2 may promote a DNA repair pathway involving Fbh1 that functions independently of Fml1 and Mus81-Eme1. Notably, the genetic interactions between dbl2 and fbh1 also support the possibility that Dbl2 promotes an Fbh1-independent pathway, which could exacerbate cell viability in the absence of Fbh1. Consequently, deleting both pathways may alleviate the sensitivity of cells to DNA-damaging agents.

Dbl2 prevents the accumulation of atypical recombination-linked DNA structures

To determine whether the deletion of dbl2 and fbh1 leads to the accumulation of similar or distinct types of recombinational intermediates, we analyzed the chromosome structure in dbl2Δ and fbh1Δ mutants using a chromosome comet assay59,60,61,62,63. In this experiment, we used synchronized haploid cells that were artificially induced into meiosis as a natural source of DSBs and subsequent recombinational repair. Previously, we reported that during synchronized haploid meiosis, recombination-linked joint molecules (JMs) persisted longer in dbl2Δ mutant cells compared to wild-type cells43. Additionally, our previous findings indicated that these JMs are Rec12-dependent, suggesting that they may arise from DSB repair rather than from DNA replication43.

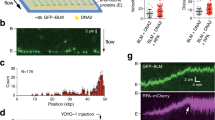

We prepared synchronous meiotic cells using a haploid pat1-114 strain, in which DSBs are formed at the 3–4-h time point, and most of them are repaired by the 5-h time point64. Samples of cells were taken 5.5 h after the induction of meiosis, at the time point when the highest accumulation of JMs in the dbl2Δ mutant was expected43 (Fig. S6). Chromosomes released from pat1-114 dbl2Δ cells, pat1-114 fbh1Δ cells, and pat1-114 control cells were separated using Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE). Pieces of agarose containing yeast chromosomes I, II, and III, along with DNA structures stacked in the gel wells, were excised and subjected to further electrophoresis under alkaline conditions to resolve the DNA structures. Following electrophoresis, the DNA was stained with a highly sensitive fluorescent dye (YOYO-1), enabling visualization of the DNA at the single-molecule level. The chromosomal structures were examined and categorized microscopically based on the criteria described in65.

In the pat1-114 dbl2Δ mutant samples, we frequently observed various types of recombination intermediates, including Y, X, ψ-like structures, and other branched structures (Fig. 3 and S7). We also identified circular DNA structures and an overrepresentation of DNA loops, both within the chromosomes and at their ends (Fig. 3). Notably, these structures were absent in the samples derived from chromosome III, which contains rDNA repeats at its ends (Fig. S7). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that this is due to the presence of chromosomal structures stacked in the well. The circular DNA structures detected in the samples derived from the pat1-114 dbl2Δ mutant could result from recombination events between repeated sequences in the genome or from recombination events linked to telomere maintenance. These observations could be explained by either the loss of Dbl2’s anti-recombinogenic function or the inappropriate activation of an alternative repair pathway in its absence.

The recombination-linked DNA structures present in strains lacking dbl2 or fbh1. Chromosome comet assay was performed on DNA samples derived from pat1-114 control cells (SP3), dbl2Δ pat1-114 (SP511), and fbh1Δ pat1-114 mutant cells (SP567). Cell samples were taken 5.5 h after the induction of synchronous haploid meiosis. DNA structures overrepresented either in the gel wells or DNA bands containing chromosomes I, II and III were divided into categories according to their frequency of occurrence – commonly, often, or rarely – in the samples derived from respective strains. The types of recombination-linked structures are marked in the figure.

In both the pat1-114 fbh1Δ and control pat1-114 samples, the Y, X, ψ-like structures, and circular structures appeared only occasionally. In the samples derived from the pat1-114 fbh1Δ strain, we frequently observed partially condensed chromosomes. The low frequency of recombination-linked chromosomal structures, and the more diffuse chromosomes observed in the pat1-114 fbh1Δ samples, may result from the delayed or impaired process of chromosome condensation. This defect in chromosome condensation complicates direct phenotypic comparisons between dbl2Δ and fbh1Δ mutants. Interestingly, the Fbh1 helicase was previously identified in a microscopy screening as a new gene required for mitotic chromosome condensation66. However, its specific role in chromosome condensation remains unclear.

Dbl2 binds preferentially to branched DNA structures

The accumulation of different types of DNA recombinational intermediates, in the absence of Dbl2, prompted us to analyze whether Dbl2 binds to specific DNA substrates. To explore this, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using fluorescently labeled DNA structures, including ssDNA, dsDNA, 3′-overhang, 5′-flap, D-loop, RF, and mobile HJ67. We failed to produce Dbl2 without a tag, despite several attempts and strategies (see Material and Methods). However, we successfully expressed and purified the Dbl2 protein fused to maltose-binding protein (MBP) to near homogeneity (Fig. S8). We assessed the relative affinities of MBP-Dbl2 toward different DNA structures by incubating varying amounts of the protein (0–160 nM) or MBP alone (200 nM) with various DNA substrates (5 nM). These experiments revealed that MBP-Dbl2 binds to all tested DNA structures, showing a slight preference for branched DNA structures such as mobile HJs, D-loops, 5′-flaps, and forks (Fig. 4). These data indicate that Dbl2 could provide activity for directing helicases and possibly other DNA repair proteins to such DNA sites and be responsible for their processing.

Dbl2 binds DNA with a slight preference for branched structures. The indicated amounts of Dbl2-MBP or MBP alone (200 nM) were incubated with 5 nM fluorescently labelled DNA substrates for 15 min at 30 °C. The products were resolved on 7% native polyacrylamide gels. Gels were scanned using a Typhoon FLA-9500 scanner and quantified by the ImageQuant TL 8.1 software. The graph presents the average results from at least three independent experiments.

Dbl2 is essential for chromosome III stability

Repetitive rDNA sequences located at the ends of chromosome III are particularly prone to genomic instability and serve as a source of recombination intermediates. To analyze this DNA region in the absence of Dbl2 and Fbh1, we separated S. pombe chromosomes using PFGE. Separation of the chromosomes revealed that chromosome III released from pat1-114 dbl2Δ and pat1-114 fbh1Δ haploid mutant cells migrates significantly faster than chromosome III released from the pat1-114 haploid control strain (Fig. 5A and 5B). We observed an increased mobility of chromosome III in the samples derived from both meiotic and stationary phase cells (Fig. 5A and 5B). To address possible synergy between dbl2 and fbh1, we further analyzed the consequences of losing both factors. Double mutants between pat1-114 dbl2 and pat1-114 fbh1 exhibited variability in chromosome III size, with some clones containing chromosome III of pat1-114 dbl2Δ size and some of pat1-114 fbh1Δ size. However, no significant additional shortening of chromosome III was observed in the double mutants compared to the single mutants (Fig. S9).

Dbl2 and Fbh1 prevent chromosome III instability and deletions. (A, B) PFGE analyzes of chromosomes from pat1-114 control cells (SP3), pat1-114 dbl2Δ (SP511), and pat1-114 fbh1Δ mutant cells (SP567). Equal numbers of cells were prepared in agarose gel plugs from meiotic and stationary phase cultures in triplicates. Synchronous meiosis was induced by Pat1 inactivation in cells arrested at the G1 phase, and samples of cells were taken 5.5 h after the induction of meiosis. Stationary phase cultures were prepared by 2-week cultivation on YES plates. (C) Analysis of the length of rDNA arrays by Southern hybridization. Chromosomes in plugs from (A and B) were digested by ScaI restriction enzyme, separated by PFGE, and hybridized with [α32P] ATP-labelled rDNA probe. The position of rDNA fragments after Southern hybridization is marked with red arrows.

Similar results were previously described for rqh1Δ mutant strains, in which the increased mobility of chromosome III was caused by the loss of rDNA repeats68,69. To test if the increased mobility of chromosome III in pat1-114 dbl2Δ and pat1-114 fbh1Δ is due to the lower number of rDNA repeats, we digested DNA released from the mutant strains by ScaI. This restriction enzyme does not cut DNA within the rDNA sequence. Because S. pombe chromosome III contains rDNA at both chromosome ends, the undigested rDNA, separated by PFGE and hybridized with an rDNA-specific probe, appears on a gel as two large DNA fragments (Fig. 5C). Our analysis confirmed that both pat1-114 dbl2Δ and pat1-114 fbh1Δ mutant strains contain shorter rDNA regions compared to wild-type, although with a marked difference in rDNA stability. While in pat1-114 fbh1Δ meiotic cells, the rDNA is shorter but relatively stable, in pat1-114 dbl2Δ meiotic cells, rDNA displays a very high level of instability, which manifests itself as increased smearing of the rDNA regions in the PFGE assay. The rDNA in the stationary phase cells is unstable in both pat1-114 dbl2Δ and pat1-114 fbh1Δ mutant strains (Fig. 5B and 5 C). The instability of genomic DNA and rDNA in the fbh1Δ mutant aligns with the observation that the fbh1Δ mutant dies after entering the stationary phase70. It was previously shown that the decreased viability of fbh1Δ during the stationary phase arises from inappropriate recombination events triggered by elevated Rad51 levels10.

rDNA instability is often accompanied by the production of extrachromosomal rDNA circles (ERCs), which are rDNA repeats popping out in the process of unequal sister chromatid recombination. Surprisingly, we did not observe increased levels of ERCs in pat1-114 dbl2Δ or pat1-114 fbh1Δ mutant strains compared to wild-type (Fig. S9).

The shortening of chromosome III is often linked to a failure to resolve structures that arise in the rDNA arrays, leading to difficulties in rDNA separation during cell division. To visualize the segregation of rDNA in dbl2Δ cells, we used a GFP-tagged version of the nucleolar Gar2 protein (Gar2-GFP), which localizes to the rDNA where transcription occurs71,72. We observed equal segregation of Gar2-GFP fluorescence in dbl2Δ cells, and we did not detect any Gar2-GFP bridges between the nascent daughter nuclei, often seen in mutants defective in rDNA segregation (Fig. S10). Similar results were recently reported for dbl2Δ using mCherry-tagged nucleolar protein Nuc1 (Nuc1-mCherry)73. These results suggest that Dbl2 is required for rDNA stability, but its absence does not increase ERC production or affect rDNA segregation.

Dbl2 and Fbh1 act in the same pathway to suppress recombination at LTR direct repeats

Our observation that Dbl2 and Fbh1 are essential for the stability of rDNA repeats prompted us to examine their impact on recombination involving other types of repeat sequences, such as LTRs present as tandem repeats at the ends of Tf2 retrotransposons. We assessed the effect of dbl2 and fbh1 on Tf2 stability by measuring the frequencies of loss of a ura4 reporter transgene inserted in the Tf2-6 transposon (Fig. 6A)74,75. Two classes of ura4- recombinants can arise following replication fork blockage at LTR sequences. First class (conversion types) are formed by Rad51-dependent gene conversion events, while the second class (deletion types) occur by both Rad51-dependent and Rad51-independent mechanisms76.

Effect of deleting fbh1, rad51, and rad52 in wild-type and dbl2Δ strains on Tf2 stability. (A) Two possible ways of ura4 loss, gene conversion, and deletion by LTR recombination, are depicted. (B) 12 independent colonies of wild-type (SP1360) and deletion strains (SP101, SP92, SP305, SP333, SP1423, SP87, SP290, SP1885) were grown in YES at 32 °C to saturation and plated onto YES + 5-FOA selective plates. Growing colonies were counted and characterized for the rearrangements by colony PCR with primers Tf2_6-F + Tf2_6R (deletion) and Tf2_6F + Tf2_2R (conversion). Statistical significance of any differences between the wild-type and mutant strains or between single and double mutants was assessed by Student’s T-test and is depicted as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Both dbl2Δ and fbh1Δ strains exhibited a significant increase in Tf2 ectopic recombination (Fig. 6B). Notably, the increase in Tf2 ectopic recombination in the fbh1Δ mutant was not further increased by deletion of dbl2Δ, suggesting that dbl2 and fbh1 may function within the same molecular pathway (Fig. 6B). Subsequently, we investigated the effects of rad51 and rad52 deletions on the frequency of ectopic recombination in dbl2Δ strains (Fig. 6B). Rad51 and Rad52 are crucial recombination proteins required for gene conversion. However, Rad52 has also been shown to function independently of Rad51 in single-strand annealing (SSA) pathways, inter-fork strand annealing (IFSA) pathways and in Rad52-dependent recombination-dependent replication (RDR), which may all lead to gene deletions77,78,79. As expected, the deletion of rad51 reduced gene conversions and substantially increased Rad52-dependent deletions. The rad51Δ dbl2Δ double mutants exhibited the same reduced level of gene conversions as the rad51Δ single mutant, suggesting that the increased gene conversions in dbl2Δ are Rad51-dependent. The level of gene deletions in rad51Δ dbl2Δ was lower compared to rad51Δ, indicating that Dbl2 may promote Rad52-mediated repair pathways, such as Rad52-dependent template switching79. To address whether the increased gene conversions in fbh1Δ also depend on Rad51, we analyzed recombination products in rad51Δ fbh1Δ double mutants. Similar to the rad51Δ single mutant, only gene deletions were observed, indicating that the elevated gene conversions in fbh1Δ require Rad51. Notably, gene deletions in rad51Δ fbh1Δ double mutants were also decreased compared to rad51Δ single mutants. Although the impact of dbl2Δ and fbh1Δ on the level of gene deletions in the rad51Δ background appears significant, further experimental validation is needed. Moreover, the frequency of ectopic recombination in both rad52Δ and rad52Δ dbl2Δ mutant strains remained close to wild-type levels, supporting the conclusion that Dbl2 and Rad52 function within the same pathway, with Rad52 acting upstream of Dbl2. Taken together, these results suggest that Dbl2 may collaborate with Fbh1 to suppress recombination between LTR repeats, and that the increased levels of ectopic recombination in the dbl2Δ mutant are Rad51- and Rad52-dependent.

Discussion

We have previously reported that Dbl2 is a novel regulator of the Fbh1 helicase, which dismantles Rad51-DNA filaments and promotes efficient DSB repair43. In particular, we have shown that the formation of Fbh1 foci is impaired in dbl2Δ cells. In the present study, we used TAP purification to confirm the interactions between Dbl2 and Fbh1, forming a conserved SCFFbh1 complex with Skp1 (Fig. 1). Moreover, TAP purification and Y2H analysis indicated that Dbl2 interacts with other DNA repair proteins, which are part of complexes exhibiting helicase or endonuclease activity, namely Fml1-MHF, RTR, and Mus81-Eme1 (Fig. 1). These protein–protein interactions suggest that Dbl2 may influence a broader spectrum of recombinational processes than previously anticipated.

Our findings highlight that the interplay between Dbl2 and the Fbh1 helicase is crucial for HR regulation. In S. pombe, there are three conserved DNA helicases, Fbh1, Srs2, and Rqh1, which have been identified as suppressing Rad51-dependent recombination at blocked RFs and template switch downstream of a collapsed RF5,9,70,78,80. Previously performed epistasis analysis has revealed that any combination of fbh1Δ, srs2Δ, and rqh1Δ results in a dramatic reduction of viability, which can be rescued by deleting Rad5180,81. Conversely, the loss of fml1 rescues the rqh1Δ sensitivity to HU, indicating that Fml1 and Rqh1 (RTR) could function within the same pathway9. In our study, epistasis analysis showed that deletion of dbl2 partially suppresses the sensitivity of fbh1Δ mutant cells to MMS, CPT, and HU, supporting the notion that Dbl2 acts in a DNA repair pathway utilizing Fbh1 (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, negative genetic interactions were observed between dbl2Δ and fml1Δ or eme1Δ, suggesting that these genes function within alternative DNA repair pathways (Fig. 2A).

These findings are consistent with a study in S. cerevisiae, where two main pathways of nascent D-loop resolution were defined using a D-loop capture assay. One pathway relies on the Srs2 helicase, while the other involves the Mph1 helicase (Fml1 in S. pombe) and the STR complex (RTR in S. pombe)30. Notably, Fbh1 does not have an ortholog in S. cerevisiae. Together, these data suggest that in fission yeast, Dbl2 with Fbh1, Srs2, and Fml1 with RTR, may represent three distinct, partially overlapping DNA repair pathways that involve Rad51-dependent recombination intermediates.

It is believed that the dissolution of nascent D-loops is the primary mechanism preventing repeat-mediated genomic instability through HR. The proposed model is further supported by our data from the LTR assay, which indicate that deletion of dbl2 increases recombination at LTR repeats while partially decreases recombination in the fbh1Δ background (Fig. 6B). This suggests that, in the absence of Dbl2, DNA lesions may be redirected into an alternative repair sub-pathway, potentially involving Fml1 or RTR (Fig. S11). However, when Dbl2 is present, DNA lesions are primarily routed to the Fbh1-dependent pathway, and without Fbh1, repair intermediates may not be correctly resolved. The importance of Dbl2 in suppressing unwanted recombination at repetitive regions is further reinforced by the increased appearance of various recombination-linked DNA structures, including circular DNA detected by the comet assay in the dbl2Δ mutant (Fig. 3) and observed instability in rDNA regions (Fig. 5).

In our opinion, the most likely molecular mechanism for the Dbl2-Fbh1 pathway involves Fbh1’s capability to disassemble the Rad51 nucleoprotein filament10. We demonstrated that Dbl2 directly interacts with Rad51 recombinase43, co-purifies with the SCFFbh1 complex (Fig. 1), and preferentially binds to branched DNA structures in vitro (Fig. 4). These results indicate that Dbl2 is critical for guiding the localization of Fbh1 to specific sites where its function is necessary (Fig. 7). Another possibility is that Dbl2 promotes the formation of a substrate for the SCFFbh1 complex, although whether Dbl2 can affect the nature of recombination intermediates remains to be addressed.

We propose that Dbl2, which preferentially binds to branched DNA structures, could facilitate the recruitment of Fbh1-Skp1 and possibly other helicases or DNA repair proteins to these sites, thereby contributing to their processing. The Fbh1 helicase is known to translocate along DNA and dissociate Rad51 from nucleofilaments. Following Rad51 displacement, the SCFFbh1 complex targets Rad51 for ubiquitination to prevent its re-loading onto DNA.

However, the observed interactions of Dbl2 with components of the pathway, utilizing Fml1-MHF and RTR (Fig. 1), suggest a more complex role for Dbl2. These interactions are consistent with studies on Mte1 which described its interaction with Mph1. In S. cerevisiae, Mte1 and Mph1 work together in a pathway where Mte1 regulates Mph1’s activities in multiple ways44,45,46. However, while deletion of MTE1 showed epistasis or suppression of mph1Δ sensitivity to HU or MMS44, dbl2Δ and fml1Δ exhibited additive sensitivity to HU, MMS, and CPT (Fig. 2A). This suggests that Dbl2 and Fml1 typically work in alternative pathways, though it does not exclude the possibility of their collaboration in specific scenarios. Such scenarios are also supported by the observed importance of Dbl2 for Fml1 foci formation56. These results demonstrate that while certain processes are conserved between the two yeasts, others have diverged. One possible reason for this divergence might be the presence of Fbh1 in S. pombe. In the absence of an Fbh1 homolog in S. cerevisiae, Mte1 functions specifically within the Fml1 pathway. However, the emergence of Fbh1 in S. pombe likely expanded Dbl2’s function to include regulation of Fbh1, thereby reducing its original importance in the Fml1 pathway.

Dbl2 also shares homology with the human ZGRF1 protein, which interacts with the RAD51 recombinase and enhances strand exchange by RAD51-RAD54 during HR47. Similar to the Dbl2-Fbh1 interactions, ZGRF1 encodes a helicase domain within its coding sequence. However, in the future, it would also be interesting to explore its interactions with other helicases and endonucleases in the context of human pathology.

In conclusion, this work reveals that Dbl2 and Fbh1 collaborate to maintain genome integrity by preventing ectopic recombination at repetitive regions. However, the observed physical and genetic interactions suggest that Dbl2 regulates a broader range of recombinational processes, which require further investigation to be fully understood.

Material and methods

Strains, growth media, and general methods

The genotypes of the strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables S1, S2, and S3, respectively. Strains carrying a deletion were purchased from Bioneer82 or constructed, as described previously83. Plasmids for protein localisation were purchased from Riken BRC84 or Addgene. Standard media (rich YES, minimal EMM2 and EMMG, sporulation media PMG-N) were used to grow and mate S. pombe strains85. When necessary, 0.15 g/l G418, 0.1 g/l nourseothricin, 0.2 g/l hygromycin, or 0.005 g/l thiamine were added. For spot assays, cells were first grown to the exponential phase (OD595 = 0.5–0.8), and then tenfold serial dilutions (in the range of 105 to 101 cells/spot) were spotted onto media in the presence or absence of a genotoxic drug (CPT, MMS, HU), and incubated for three days. S. pombe was transformed using the lithium acetate method83. Microscopy used to analyze Dbl2-YFP, Mus81-YFP and Rmi1-mNG localization was performed, as described previously86. Briefly, cells were incubated in minimal EMM2 media lacking thiamine for 22–26 h at 30 °C, spun down, spread on a poly-L-lysine-coated coverslip and mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Labs).

Tandem affinity purification

Cells expressing Dbl2-TAP were grown in a YES medium until reaching mid-log phase (OD595 = 0.7–0.8) at 32 °C and harvested by centrifugation (4000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C; Z 36 HK, HERLME LaborTechnik, Wehingen, Germany). Yeast cell powder (80 g) was prepared from frozen cell pellets using a SPEX SamplePrep 6770 Freezer/Mill (SPEX SamplePrep, Metuchen, NJ, USA) cooled by liquid nitrogen. A yeast powder was mixed with an IPP150 buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, 200 U/ml of Benzonase® Nuclease, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, and complete protease and phosphatase inhibitors) in a ratio of 1 g of powder to 3 mL of IPP150 buffer. Proteins were extracted into IPP150 buffer for 20 min at 4 °C on a rotary wheel. Protein extract was prepared by centrifugation (40000xg, 20 min, 4 °C; Z 36 HK, HERLME LaborTechnik, Wehingen, Germany) and affinity purified, as described previously, with some modifications48,87. Briefly, 500 µL of IgG Sepharose™ 6 Fast Flow beads (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) were equilibrated with an IPP150 buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF), mixed with protein extract and incubated on a rotary wheel for 2 h at 4 °C. Beads with bound proteins were washed with 5 bead volumes of IPP150 buffer followed by washing with 3 bead volumes of TEV cleavage buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT). The cleavage step was performed in 2 mL of TEV cleavage buffer supplemented with 600 U of Turbo TEV protease (MoBiTec GmbH, Goettingen, Germany) for 2 h at 16 °C. Subsequently, 2 mL of eluate was supplemented with 6 µL of 1 M CaCl2 and combined with 6 mL of Calmodulin binding buffer 1 (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM imidazole, 1 mM Mg-acetate, 2 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Next, 100 µL of Calmodulin Sepharose™ 4B beads (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) was equilibrated with Calmodulin binding buffer 1, combined with a mixture of eluate and Calmodulin binding buffer 1 and incubated on the rotary wheel for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads with bound proteins were washed with 3 bead volumes of Calmodulin binding buffer 1 and 2 bead volumes of Calmodulin binding buffer 2 (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Mg-acetate, 2 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The proteins were step-eluted using a bead volume of elution buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Mg-acetate, 2 mM EGTA and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Eluted fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained using silver staining to follow the elution profile88. Eluates from peak fractions were combined and subjected to LC–MS/MS analysis.

LC–MS/MS analysis

Proteomic analysis was performed, as described previously48,87. Briefly, the samples were reduced using 5 mM DTT (30 min, 60 °C), alkylated by the addition of 15 mM iodoacetamide (20 min, 25 °C, in the dark), and the alkylation reaction was quenched in the presence of 5 mM DTT. Subsequently, a total of 0.5 μg of modified sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM phosphate inhibitor mix (β-glycerophosphate, Na3VO4, KF, and disodium diphosphate) were added to the protein mixture, and the samples were digested overnight at 37 °C. The mixture was acidified by the addition of 0.5% TFA to stop the trypsin reaction, and the peptide solution was purified by microtip C18 SPE and dried by vacuum centrifugation in the Concentrator Plus (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). For LC–MS/MS analysis, 5 μl of peptides per sample was loaded onto a nanotrap column (PepMap100 C18, 300 µm i.d. × 5 mm, 5 µm particle size, Dionex, CA, USA) and onto an EASY-Spray C18 analytical column with an integrated nanospray emitter (75 μm × 500 mm, 5-μm particle size, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) using the Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano system (Dionex, CA, USA). The peptides were separated on a 1 h gradient from 3 to 43% B. Two mobile phases were used: 0.1% FA (v/v) (A) and 80% ACN (v/v) with 0.1% FA (B). Eluted peptides were sprayed directly into an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), operating in data-dependent mode, using the Top15 strategy to select precursor ions for the HCD fragmentation89. Each sample was analyzed in two technical replicates, and the datasets obtained were processed by MaxQuant (1.6.17.0)90 with its built-in Andromeda search engine, using carbamidomethylation (C) as a permanent modification and phosphorylation (STY), acetylation (protein N-terminus) and oxidation (M) as variable modifications. Relative quantities of individual proteins were determined by the built-in label-free quantification (LFQ) algorithm MaxLFQ, which provides normalized LFQ intensities for the proteins identified91. The search was done amongst two S. pombe protein databases (UniProt, downloaded 12.11.2021, and PomBase, downloaded 17.7.2020).

Yeast two-hybrid analysis

Full-length coding regions for Ssb1, Ssb2, Ssb3, Ctp1, Mre11, Nbs1, Rad50, Rad52, Rad55, Rad57, Sfr1, Swi5, Rad51, Rad54, Rmi1, Top3, Rqh1, Srs2, Fml1, Mhf1, Mhf2, Fbh1, Skp1, Mus81, Dbl2, and Pcn1 were amplified from cDNA with primers that added a 5’ SfiI and 3’SmaI or BamHI restriction sites and were then cloned into plasmid pGBKT7 (Clontech) for GAL4 DNA-binding domain bait constructs, or into plasmid pGADT7 (Clontech) for GAL4 activation domain prey constructs. All inserts were verified by sequencing. Lithium acetate transformation was used to introduce bait and prey plasmids into the S. cerevisiae strain PJ69-4a (Clontech). Transformants were tested for protein–protein interactions by spotting onto an SD minimal medium lacking Leu, Trp, and His (SD-LWH) or Leu, Trp, and Ade (SD-LWA). At least two independent transformations and spot tests were performed.

Construct design, expression, and purification of Dbl2

The dbl2 gene was introduced into expression vectors to produce a protein with various affinity tags, including MBP-Dbl2 (p199), 6xHis-MBP-Dbl2 (p192), 6xHis-Dbl2 (p232), GST-Dbl2 (p233), His6-NusA-Dbl2 (p193), His6-mOCR-Dbl2 (p194), His6-SUMO-Dbl2 (p195), His6-γcrystallin-Dbl2 (p196), Dbl2-mOCR-His6 (p197), and Dbl2-GyrA-CBD (p198) (Supplementary Table S2). The resulting tagged full-length constructs were transformed into several E. coli strains BL21(DE3), BL21(DE3)RIPL, Rosetta(DE3)pLysS, and Arctic (DE3)RIL and protein expression was induced by different conditions (1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 37 °C, 0.1 mM IPTG for 12 h at 28 °C, or 0.1 mM IPTG for 24 h at 11 °C in case of Arctic (DE3) RIL E. coli strain). The highest expression was achieved with MBP-Dbl2 in Rosetta (DE3)pLysS E. coli strain, His6-mOCR-Dbl2, Dbl2-mOCR-His6, and His6-SUMO-Dbl2 in BL21(DE3)RIPL E. coli strain induced with 1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 37 °C. Based on the solubility test of overexpressed proteins, MBP-Dbl2 in the Rosetta(DE3)pLysS E. coli strain was selected for protein purification. The cells were grown at 37 °C to OD600 ~ 1 and induced by 1 mM IPTG at 37 °C for 3 h. The cell pellet (30 g) was resuspended in 100 ml of buffer containing 20 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.5, 100 mM sucrose, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% NP40 and complete protease inhibitors (Roche). The cells were lysed by sonication, centrifuged, and the resulting supernatant was loaded onto a 5 ml HiTrap SP Fast Flow column (Cytiva). The column was washed in buffer K (20 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% NP40) containing 60 mM KCl, and proteins were eluted using a 50 ml gradient of 60–600 mM KCl in buffer K. The fractions containing Dbl2 were pooled and incubated with 2 ml of Amylose Resin High Flow (NEB) for 1 h at 4 °C. The resin was washed with 50 ml of buffer K containing 300 mM KCl, and the proteins were eluted with 5 mM maltose in buffer K containing 300 mM KCl (7 × 2 ml). The fractions containing Dbl2 were mixed, concentrated to 0.5 ml, using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter, and loaded onto Superdex 200 10/300 GL gel filtration column (Cytiva) equilibrated in buffer K containing 300 mM KCl. The Dbl2-containing fractions were then concentrated by Amicon Ultra, aliquoted, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C.

EMSA

The MBP-Dbl2 protein (10/20/40/80/160 nM) or MBP alone (200 nM) were incubated with 5 nM fluorescently labelled DNA substrates67 for 15 min at 30 °C in a 50 mM KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1 mg/ml BSA. After incubation, glycerol was added to a final concentration of 10% and EDTA to 10 mM. Subsequently, the samples were resolved on 7% native polyacrylamide gels in a 0.5 × TBE buffer (45 mM Tris ultrapure, 45 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA). The gels were scanned using a Typhoon FLA-9500 scanner (GE Healthcare) and quantified by ImageQuant TL 8.1 software (Cytiva).

Separation of S. pombe chromosomes by PFGE

The pat1-114 haploid control cells, as well as the haploid mutant cells pat1-114 dbl2Δ and pat1-114 fbh1Δ, were synchronized and released into meiosis, as described earlier92. The DNA plug preparation method was adapted from65 for S. cerevisiae and adjusted for S. pombe. Briefly, the 1.6 × 108 cells of each strain were treated with 2 mM NaN3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 min, washed with 1 ml of 50 mM EDTA pH 8.0 (Merck), spun down 30 s 850 × g. The pellet was suspended in 80 μl of lytic solution (1 M Sorbitol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 0.1 M EDTA pH 8.0 with 2 mg/ml lyticase, 2 mg/ml zymolyase (BioShop, Burlington, ON, Canada) and mixed gently with an equal volume of 1.2% low melting point agarose (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). The mixture was solidified in a 2 ml syringe (Becton–Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at 4 °C, and then a block of agarose-containing cells was cut into equal plugs. The plugs were placed in 2 ml Eppendorf tubes and covered with a 1 ml zymolyase solution (1 M Sorbitol, 20 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 2 mg/ml lyticase, 1 mg/ml zymolyase) and digested at 37 °C, with rotation (4 rpm) in an SB3 (Bibby Sterlin LTD, Stone, UK) rotator overnight. Then the plugs were rinsed twice with 2 ml of 50 mM EDTA pH 8.0 and 1 ml proteinase solution [(50 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1% N-lauroylsarcosine, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mg proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μg RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich)] was added. After overnight incubation at 37 °C with rotation, the proteinase solution was removed, and the plugs were rinsed twice with 2 ml of 50 mM EDTA, and incubated in 2 ml 1 × TE for 1 h, with rotation. The plugs were placed in the wells of a 0.8% D5 agarose (Conda, Torrejon de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain) gel in 1 × TAE and sealed with the same agarose. DNA was separated for 72 h in 1 × TAE at 14 °C using CHEF Mapper® XA Pulsed Field Electrophoresis System (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) with settings: switch time: 20–60 min; ramping linear, angle: 106°, voltage 2 V/cm, as suggested in93. Finally, the gel was stained by agitation, with 300 ml of 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich), washed twice with water for 30 min, and the yeast chromosomes were photographed using a UV light (302 nm UV) for DNA visualization, with a charge-coupled device camera (Fluorchem Q Multi Image III, Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA).

Detection of the length of the rDNA tandem repeats

The DNA plugs were digested by ScaI restriction enzymes (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which does not cut within rDNA arrays located at the ends of chromosome III in S. pombe, according to94. PFGE was performed as described in63. In brief, the samples were separated in 0.8% agarose gel (D5 agarose in 1 × TAE) for 24 h in a 1 × TAE buffer at 6 V/cm, 12 °C, ramping 0.8, angle 120°, switch time 60–85 s, using a CHEF Mapper® XA Pulsed Field Electrophoresis System. The DNA was stained with 0.5 μg/ml SYBR Gold (Invitrogen, USA) for 30 min, washed twice with water for 15 min, and photographed using a 302-nm UV light and GFP filter for DNA visualization with a charge-coupled device camera (Fluorchem Q Multi Image III, Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA). The DNA was transferred by capillary transfer onto nylon membranes (GeneScreen Plus, PerkinElmer, Inc., Germany) and Southern hybridization with the [α32P] ATP-labelled rDNA probe was performed. The 119 bp-long rDNA probe was prepared using the primers rDNA_probe.lw + rDNA_probe.up and labeled with [α32P] ATP, using a DecaLabel DNA Labeling Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Radioactive signals were detected using a FujiFilm FLA-7000 scanner.

Detection of extra-chromosomal rDNA circles (ERCs)

The DNA plugs digested by ScaI were subjected to electrophoresis for 16 h in 0.8% D5 agarose in 1xTAE at 18 °C, 1 V/cm. Then, capillary transfer onto nylon membranes and Southern hybridization with the [α32P] ATP-labelled rDNA probe were performed. Radioactive signals were detected using a FujiFilm FLA-7000 scanner.

Chromosome comet assay

The chromosome comet assay is a single-molecule approach for the detection of chromosomal DNA breakage and chromosome structures. The basis of the assay is described in63. The assay was performed as in63, with some modifications due to the differences in the lengths of the chromosomal structures. The DNA structures present in S. pombe chromosomes I, II and III or the DNA structures stacked in the PFGE gel wells were excised from the gels after ethidium bromide staining. Agarose bands were placed on poly-L-lysine coated microscopic slides (CometSlide, Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and covered with 40 μl of 0.6% New Sieve Low Melting Point agarose (Conda). After agarose solidification, to denature the chromosomal DNA, the slide was placed in 30 mM NaOH (POCh), 1 mM EDTA, pH > 12, for 10 min. The electrophoresis was performed under denaturing conditions, in 30 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, pH > 12, for 20 min, with cooling, at 0.1 A, using the Comet assay ESII (Trevigen). Then, agarose neutralization and DNA precipitation were performed by soaking slides 3 times for 30 min in N/P solution (50% ethanol (Polmos, Warszawa, Poland), 1 mg/ml spermidine (Sigma-Aldrich), and 20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4). Chromosomal DNA was stained with the fluorescent dye YOYO-1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Poland) by spotting the staining solution [0.25 mM YOYO-1, 2.5% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.5% sucrose (Schwarz/Mann, Orangeburg, NY, USA)] on the slide. The DNA structures were examined using an Axio Imager M2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), a 38HE filter set, and documented using an AxioCam MRc5 Digital Camera (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Images were collected at 1000 × magnification, archived, and processed using an Axio Vision 4.8 (Zeiss).

LTR ectopic recombination assay

A ura4 loss assay was performed, as described previously74. Briefly, 12 independent colonies of the wild-type and mutant strains were picked from EMMG-ura plates to isolate ura4+ starting populations. The cultures were inoculated in YES media at the same low density. After growth at 32ºC for 24 h, 1 × 105 cells were plated onto YES + 5-FOA selective plates (5-FOA, 1 mg/ml) and grown for 3–4 days. 1 × 102 cells were plated onto YES media to estimate cell viability and plating efficiency. Growing colonies were counted, and 40 colonies from each genotype were characterized for rearrangements by colony PCR with primers Tf2_6-F + Tf2_6R (eviction) and Tf2_6F + Tf2_2R (conversion). The Student’s T-test was used to assess the statistical significance of any differences and is depicted as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Western blotting analysis

Fml1 and Fbh1 were fused to a TAP tag at their C-termini and expressed from their endogenous promoters in wild-type and dbl2Δ strains, as previously described48. For each strain, 100 ml of culture was grown in a YES medium, until reaching mid-log phase (OD595 = 0.7), and cells were collected by centrifugation (2650xg for 5 min at 4 °C). Cell lysates were prepared in a lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, complete protease and 1 mM PMSF)95 by vortexing cell pellets with glass beads, 3 times for 2 min, followed by a 2 min break and cooling on ice. Crude lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 19 000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Extracted proteins (100 μg per lane) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (PVDF, 0,45 μm, Millipore). For immunodetection of TAP-tagged helicases, an HRP-conjugated anti-TAP antibody (Genescript) was used at a dilution of 1 μg/ml in Tris buffer saline (TBS). A mouse anti-β-tubulin antibody (Invitrogen) was used as a reference at dilution 1:2500, followed by a secondary anti-mouse horse radish peroxidase conjugated antibody (1:5000). The quantification of immunodetected bands was performed using ImageJ software (National Institute of Health). The one-tailed Student’s T-tests for paired comparison were performed on the data from the three independent experiments.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Dziadkowiec, D., Kramarz, K., Kanik, K., Wiśniewski, P. & Carr, A. M. Involvement of Schizosaccharomyces pombe rrp1 + and rrp2 + in the Srs2- and Swi5/Sfr1-dependent pathway in response to DNA damage and replication inhibition. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 8196–8209 (2013).

Mimitou, E. P. & Symington, L. S. DNA end resection—Unraveling the tail. DNA Repair (Amst) 10, 344–348 (2011).

Baranowska, G., Misiorna, D., Białek, W., Kramarz, K. & Dziadkowiec, D. Replication stress response in fission yeast differentially depends on maintaining proper levels of Srs2 helicase and Rrp1, Rrp2 DNA translocases. PLoS ONE 19, e0300434 (2024).

Schmid, W. & Fanconi, G. Fragility and spiralization anomalies of the chromosomes in three cases, including fraternal twins, with Fanconi’s anemia, type Estren-Dameshek. Cytogenet. Genome. Res. 20, 141–149 (1978).

Lorenz, A., Osman, F., Folkyte, V., Sofueva, S. & Whitby, M. C. Fbh1 limits Rad51-dependent recombination at blocked replication forks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 4742–4756 (2009).

Pietrobon, V. et al. The Chromatin Assembly Factor 1 Promotes Rad51-Dependent Template Switches at Replication Forks by Counteracting D-Loop Disassembly by the RecQ-Type Helicase Rqh1. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001968 (2014).

Wong, I. N. et al. The Fml1-MHF complex suppresses inter-fork strand annealing in fission yeast. Elife 8, (2019).

Nandi, S. & Whitby, M. C. The ATPase activity of Fml1 is essential for its roles in homologous recombination and DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 9584–9595 (2012).

Sun, W. et al. The FANCM Ortholog Fml1 promotes recombination at stalled replication forks and limits crossing over during DNA double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. 32, 118–128 (2008).

Tsutsui, Y. et al. Multiple regulation of Rad51-Mediated homologous recombination by fission yeast Fbh1. PLoS Genet 10, e1004542 (2014).

Whitby, M. C. The FANCM family of DNA helicases/translocases. DNA Repair (Amst) 9, 224–236 (2010).

Xue, X., Sung, P. & Zhao, X. Functions and regulation of the multitasking FANCM family of DNA motor proteins. Genes. Dev. 29, 1777–1788 (2015).

Basbous, J. & Constantinou, A. A tumor suppressive DNA translocase named FANCM. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 54, 27–40 (2019).

Prakash, R. et al. Yeast Mph1 helicase dissociates Rad51-made D-loops: implications for crossover control in mitotic recombination. Genes Dev. 23, 67–79 (2009).

Lorenz, A. et al. The Fission Yeast Fancm Ortholog Directs Non-Crossover Recombination During Meiosis. Science 1979(336), 1585–1588 (2012).

Gari, K., Décaillet, C., Stasiak, A. Z., Stasiak, A. & Constantinou, A. The fanconi anemia protein FANCM can promote branch migration of holliday junctions and replication forks. Mol. Cell. 29, 141–148 (2008).

Gari, K., Décaillet, C., Delannoy, M., Wu, L. & Constantinou, A. Remodeling of DNA replication structures by the branch point translocase FANCM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 16107–16112 (2008).

Crismani, W. et al. FANCM Limits Meiotic Crossovers. Science (1979) 336, 1588–1590 (2012).

Singh, T. R. et al. MHF1-MHF2, a histone-fold-containing protein complex, participates in the fanconi anemia pathway via FANCM. Mol. Cell. 37, 879–886 (2010).

Bhattacharjee, S. et al. MHF1-2/CENP-S-X performs distinct roles in centromere metabolism and genetic recombination. Open Biol. 8, 180010 (2018).

Tao, Y. et al. The structure of the FANCM–MHF complex reveals physical features for functional assembly. Nat. Commun.. 3, 782 (2012).

Yan, Z. et al. A Histone-Fold Complex and FANCM Form a conserved dna-remodeling complex to maintain genome stability. Mol. Cell. 37, 865–878 (2010).

Wang, W. et al. Structural peculiarities of the (MHF1-MHF2) 4 octamer provide a long DNA binding patch to anchor the MHF-FANCM complex to chromatin: A solution SAXS study. FEBS Lett 587, 2912–2917 (2013).

Zakharyevich, K., Tang, S., Ma, Y. & Hunter, N. Delineation of joint molecule resolution pathways in meiosis identifies a crossover-specific resolvase. Cell 149, 334–347 (2012).

De Muyt, A. et al. BLM Helicase Ortholog Sgs1 Is a central regulator of meiotic recombination intermediate metabolism. Mol. Cell. 46, 43–53 (2012).

Oh, S. D. et al. BLM Ortholog, Sgs1, prevents aberrant crossing-over by suppressing formation of multichromatid joint molecules. Cell 130, 259–272 (2007).

Gupta, S. V. & Schmidt, K. H. Maintenance of yeast genome integrity by recq family DNA Helicases. Genes (Basel) 11, 205 (2020).

Cejka, P., Plank, J. L., Bachrati, C. Z., Hickson, I. D. & Kowalczykowski, S. C. Rmi1 stimulates decatenation of double Holliday junctions during dissolution by Sgs1–Top3. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1377–1382 (2010).

Wu, L. et al. BLAP75/RMI1 promotes the BLM-dependent dissolution of homologous recombination intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 4068–4073 (2006).

Piazza, A. et al. Dynamic processing of displacement loops during recombinational DNA repair. Mol. Cell. 73, 1255-1266.e4 (2019).

Fasching, C. L., Cejka, P., Kowalczykowski, S. C. & Heyer, W.-D. Top3-Rmi1 dissolve Rad51-mediated D loops by a topoisomerase-based mechanism. Mol. Cell. 57, 595–606 (2015).

Talhaoui, I., Bernal, M. & Mazón, G. The nucleolytic resolution of recombination intermediates in yeast mitotic cells. FEMS Yeast Res. 16, 065 (2016).

Giaccherini, C., Scaglione, S., Coulon, S., Dehé, P.-M. & Gaillard, P.-H.L. Regulation of Mus81-Eme1 structure-specific endonuclease by Eme1 SUMO-binding and Rad3ATR kinase is essential in the absence of Rqh1BLM helicase. PLoS Genet 18, e1010165 (2022).

Kaliraman, V., Mullen, J. R., Fricke, W. M., Bastin-Shanower, S. A. & Brill, S. J. Functional overlap between Sgs1–Top3 and the Mms4–Mus81 endonuclease. Genes Dev. 15, 2730–2740 (2001).

Bastin-Shanower, S. A., Fricke, W. M., Mullen, J. R. & Brill, S. J. The mechanism of Mus81-Mms4 cleavage site selection distinguishes it from the homologous endonuclease Rad1-Rad10. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 3487–3496 (2003).

Whitby, M. C., Osman, F. & Dixon, J. Cleavage of model replication forks by fission yeast mus81-eme1 and budding yeast Mus81-Mms4. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6928–6935 (2003).

Kanagaraj, R., Saydam, N., Garcia, P. L., Zheng, L. & Janscak, P. Human RECQ5β helicase promotes strand exchange on synthetic DNA structures resembling a stalled replication fork. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 5217–5231 (2006).

Machwe, A., Xiao, L., Lloyd, R. G., Bolt, E. & Orren, D. K. Replication fork regression in vitro by the Werner syndrome protein (WRN): Holliday junction formation, the effect of leading arm structure and a potential role for WRN exonuclease activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 5729–5747 (2007).

Ralf, C., Hickson, I. D. & Wu, L. The bloom’s syndrome helicase can promote the regression of a model replication fork. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22839–22846 (2006).

Popuri, V. et al. The human RecQ Helicases, BLM and RECQ1, display distinct DNA substrate specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17766–17776 (2008).

Fugger, K. et al. FBH1 Catalyzes regression of stalled replication forks. Cell. Rep. 10, 1749–1757 (2015).

Osman, F. & Whitby, M. Exploring the roles of Mus81-Eme1/Mms4 at perturbed replication forks. DNA Repair. (Amst) 6, 1004–1017 (2007).

Polakova, S. et al. Dbl2 Regulates Rad51 and DNA joint molecule metabolism to ensure proper meiotic chromosome segregation. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006102 (2016).

Silva, S. et al. Mte1 interacts with Mph1 and promotes crossover recombination and telomere maintenance. Genes Dev. 30, 700–717 (2016).

Xue, X. et al. Differential regulation of the anti-crossover and replication fork regression activities of Mph1 by Mte1. Genes Dev. 30, 687–699 (2016).

Yimit, A. et al. MTE1 Functions with MPH1 in double-strand break repair. Genetics 203, 147–157 (2016).

Brannvoll, A. et al. The ZGRF1 helicase promotes recombinational repair of replication-blocking DNA damage in human cells. Cell Rep 32, 107849 (2020).

Cipak, L. et al. An improved strategy for tandem affinity purification-tagging of Schizosaccharomyces pombe genes. Proteomics 9, 4825–4828 (2009).

Rigaut, G. et al. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 1030–1032 (1999).

Ramalingam, A. & Prendergast, G. C. Bin1 Homolog Hob1 supports a Rad6-Set1 pathway of transcriptional repression in fission yeast. Cell Cycle 6, 1655–1662 (2007).

Gao, J. et al. NAP1 Family histone chaperones are required for somatic homologous recombination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 1437–1447 (2012).

Kim, W. J., Park, E. J., Lee, H., Seong, R. H. & Park, S. D. Physical interaction between Recombinational Proteins Rhp51 and Rad22 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30264–30270 (2002).

Tsutsui, Y., Khasanov, F. K., Shinagawa, H., Iwasaki, H. & Bashkirov, V. I. Multiple interactions among the components of the recombinational DNA repair system in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 159, 91–105 (2001).

Van Dyck, E., Hajibagheri, N. M. A., Stasiak, A. & West, S. C. Visualisation of human rad52 protein and its complexes with hrad51 and DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 284, 1027–1038 (1998).

Shinohara, A., Shinohara, M., Ohta, T., Matsuda, S. & Ogawa, T. Rad52 forms ring structures and co-operates with RPA in single-strand DNA annealing. Genes Cells 3, 145–156 (1998).

Yu, Y. et al. A proteome-wide visual screen identifies fission yeast proteins localizing to DNA double-strand breaks. DNA Repair. (Amst) 12, 433–443 (2013).

van Leeuwen, J., Pons, C., Boone, C. & Andrews, B. J. Mechanisms of suppression: The wiring of genetic resilience. BioEssays 39, 1700042 (2017).

Oh, M., Choi, I. S. & Park, S. D. Topoisomerase III is required for accurate DNA replication and chromosome segregation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 4022 (2002).

Lewinska, A., Miedziak, B. & Wnuk, M. Assessment of yeast chromosome XII instability: Single chromosome comet assay. Fungal Genet. Biol. 63, 9–16 (2014).

Adamczyk, J. et al. Affected chromosome homeostasis and genomic instability of clonal yeast cultures. Curr. Genet. 62, 405–418 (2016).

Lewinska, A., Miedziak, B., Kulak, K., Molon, M. & Wnuk, M. Links between nucleolar activity, rDNA stability, aneuploidy and chronological aging in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biogerontology 15, 289–316 (2014).

Deregowska, A. et al. Shifts in rDNA levels act as a genome buffer promoting chromosome homeostasis. Cell Cycle 14, 3475–3487 (2015).

Krol, K. et al. Lack of G1/S control destabilizes the yeast genome via replication stress-induced DSBs and illegitimate recombination. J Cell Sci 131, (2018).

Young, J. A., Hyppa, R. W. & Smith, G. R. Conserved and nonconserved proteins for meiotic DNA breakage and repair in yeasts. Genetics 167, 593–605 (2004).

Krol, K. et al. Ribosomal DNA status inferred from DNA cloud assays and mass spectrometry identification of agarose-squeezed proteins interacting with chromatin (ASPIC-MS). Oncotarget 8, 24988–25004 (2017).

Petrova, B. et al. Quantitative analysis of chromosome condensation in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 984–998 (2013).

Matulova, P. et al. Cooperativity of Mus81·Mms4 with Rad54 in the Resolution of Recombination and Replication Intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 7733–7745 (2009).

Win, T. Z., Goodwin, A., Hickson, I. D., Norbury, C. J. & Wang, S.-W. Requirement for Schizosaccharomyces pombe Top3 in the maintenance of chromosome integrity. J. Cell. Sci. 117, 4769–4778 (2004).

Coulon, S. et al. Slx1-Slx4 Are Subunits of a Structure-specific Endonuclease That Maintains Ribosomal DNA in Fission Yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15, 71–80 (2004).

Morishita T. et al. Role of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe F-Box DNA Helicase in Processing Recombination Intermediates. Mol Cell Biol 25, 8074–8083 (2005).

Trumtel, S., Léger-Silvestre, I., Gleizes, P.-E., Teulières, F. & Gas, N. Assembly and functional organization of the nucleolus: Ultrastructural analysis of saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11, 2175–2189 (2000).

Shimada, T., Yamashita, A. & Yamamoto, M. The fission yeast meiotic regulator mei2p forms a dot structure in the horse-tail nucleus in association with the sme2 locus on chromosome II. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14, 2461–2469 (2003).

Yamamoto, T. G. et al. Histone H2A insufficiency causes chromosomal segregation defects due to anaphase chromosome bridge formation at rDNA repeats in fission yeast. Sci. Rep. 9, 7159 (2019).

Zaratiegui, M. et al. CENP-B preserves genome integrity at replication forks paused by retrotransposon LTR. Nature 469, 112–115 (2011).

Sehgal, A., Lee, C. Y. S. & Espenshade, P. J. SREBP controls oxygen-dependent mobilization of retrotransposons in fission yeast. PLoS Genet 3, 1389–1396 (2007).

Ahn, J. S., Osman, F. & Whitby, M. C. Replication fork blockage by RTS1 at an ectopic site promotes recombination in fission yeast. EMBO J. 24, 2011–2023 (2005).

Morrow, C. A. et al. Inter-Fork Strand Annealing causes genomic deletions during the termination of DNA replication. Elife 6, (2017).

Jalan, M., Oehler, J., Morrow, C. A., Osman, F. & Whitby, M. C. Factors affecting template switch recombination associated with restarted DNA replication. Elife 8, (2019).

Kishkevich, A. et al. Rad52’s DNA annealing activity drives template switching associated with restarted DNA replication. Nat. Commun. 13, 7293 (2022).

Osman, F., Dixon, J., Barr, A. R. & Whitby, M. C. The F-Box DNA Helicase Fbh1 Prevents Rhp51-Dependent Recombination without Mediator Proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 8084–8096 (2005).

Doe, C. L. The involvement of Srs2 in post-replication repair and homologous recombination in fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1480–1491 (2004).

Kim, D. U. et al. Analysis of a genome-wide set of gene deletions in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 617–623 (2010).

Gregan, J. et al. High-throughput knockout screen in fission yeast. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2457–2464 (2006).

Matsuyama, A. et al. ORFeome cloning and global analysis of protein localization in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 841–847 (2006).

Sabatinos, S. A. & Forsburg, S. L. Molecular genetics of schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 470, 759–795 (2010).

Rabitsch, K. P. et al. Two Fission Yeast Homologs of Drosophila Mei-S332 Are Required for Chromosome Segregation during Meiosis I and II. Curr. Biol. 14, 287–301 (2004).

Cipak, L. et al. Tandem affinity purification protocol for isolation of protein complexes from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. STAR Protoc. 3, 101137 (2022).

Rabilloud, T., Carpentier, G. & Tarroux, P. Improvement and simplification of low-background silver staining of proteins by using sodium dithionite. Electrophoresis 9, 288–291 (1988).

Michalski, A. et al. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics using Q Exactive, a high-performance benchtop quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Mol Cell Proteomics 10, M111.011015 (2011).

Cox, J. & Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 (2008).

Cox, J. et al. Accurate Proteome-wide Label-free Quantification by Delayed Normalization and Maximal Peptide Ratio Extraction. Termed MaxLFQ. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 2513–2526 (2014).

Yamashita, A., Sakuno, T., Watanabe, Y. & Yamamoto, M. Synchronous Induction of Meiosis in the Fission Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2017, pdb.prot091777 (2017).

Pai, C.-C., Walker, C. & Humphrey, T. C. Using Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis to Analyze Schizosaccharomyces pombe Chromosomes and Chromosomal Elements. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2018, pdb.prot092023 (2018).

Pasero, P. & Marilley, M. Size variation of rDNA clusters in the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiea and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Gen. Genet 236–236, 448–452 (1993).

Misova, I. et al. Repression of a large number of genes requires interplay between homologous recombination and HIRA. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 1914–1934 (2021).

Acknowledgements