Abstract

One of the practical limitations of solid-state superconducting quantum processors is the collision of the qubit resonance frequencies, caused by their deviation from the design specifications due to the low reproducibility in qubit fabrication. Josephson junction 100 nm-scale nonlinear inductance of the qubits still suffers from Dolan-bridge shadow evaporation process. Here, we report on a robust wafer-scale Al/AlOx/Al Dolan-bridge Josephson junction (JJ) process using preliminary shadow evaporation bias resist mask correction and comprehensive oxidation optimization. We introduce a topology correction model for two-layer resist mask biasing at a wafer-scale, which takes into account an evaporation source geometry. It results in Josephson junction area variation coefficient (\(\:{CV}_{A}\)) improvement down to 1.1% for the critical dimensions from 130 × 170 nm2 to 130 × 670 nm2 over 70 × 70 mm2 (49 cm2) wafer working area. Next, we investigate JJ oxidation process (oxidation method, pressure and time) and its impact on the room temperature resistance reproducibility. Finally, we combine both shadow evaporation bias correction and oxidation best practices for 4-inch wafers, improving \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) down to 6.0/5.2/4.1% for 0.025 µm2 JJ area and 4.0/3.4/2.3% for 0.090 µm2 JJ area for 49/25/16 cm2 wafer working area correspondingly. The proposed model and oxidation method can be useful for robust wafer-scale superconducting quantum processors fabrication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are several promising quantum computing platforms, including trapped ions1,2 silicon photonics3 semiconductor quantum dots4,5 NV centre in diamonds6,7 superconducting quantum bits8,9,10,11 etc. Quantum processors based on superconducting artificial atoms (Josephson junction qubits) are distinguished by good scalability and control. Recently, several superconducting NISQ processors have been demonstrated, including 54-qubits Sycamore quantum processor (Google)12127-qubit Eagle and 1121-qubit Condor processors (IBM)13,14 and others15,16,17. However, qubits frequency crowding is still an issue for quantum processors scalability especially for fixed-frequency transmon qubits platform. One has to detune qubits resonance frequencies after quantum processors fabrication and cryogenic characterization. For example, in order to scale up beyond 1000 superconducting qubits with a cross-resonance gate architecture18less than 6 MHz qubit frequencies standard deviation is required. Qubit resonance frequency collisions (crowding) lead to bad energy levels design, increased quantum gates time and negative factors decreasing quantum processors gates fidelity19,20. From the other hand, high-fidelity readout of superconducting quantum processors requires broadband quantum-limited cryogenic parametric amplifiers. Two well-known approaches in the field are Impedance-Matched Parametric Amplifiers (IMPA)21,22,23 and Josephson Travelling Wave Parametric amplifier (JTWPA)24,25. JTWPA are also very demanding to Josephson junction parameters reproducibility as they consist of hundreds identical elementary cells (LC-C oscillators) involved in a parametric amplification process. JTWPA ensure an exponentially increasing gain in case of high (98%) elementary cells electrical parameters reproducibility26,27.

Josephson junction area and tunnel barrier thickness variations are the key factors influencing the resonance frequency of superconducting qubits. There are two common methods for Josephson junction evaporation called Dolan bridge technique and Manhattan style process. Manhattan process doesn’t require a fragile suspended resist bridge and less sensitive to resist thickness variation that allows increasing JJ area reproducibility. But Dolan bridge technique does not require large evaporation angles, unlike Manhattan junctions, which leads to improved line edge roughness. Moreover, it enables the fabrication of an array of series-connected junctions for fluxonium qubit and quantum-limited parametric amplifier applications9,23. For example, decreasing of room temperature resistance variation coefficients to \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) = 2.3% 28,29 is demonstrated for 39 mm2 chip for 0.015–3.27 μm2 Josephson junction areas. Recently, there were several techniques proposed to improve room temperature resistance and area variation coefficients over a wafer (Table 1). The best achieved reproducibility for Dolan bridge Josephson junctions is \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) down to 0.8–3.7% for 0.02–0.08 µm2 areas inside 18 cm2 working area on 4-inch wafers30. For Manhattan style junctions \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) = 3.5%31 and \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) = 7.0%32 is achieved for 49 cm2 and 52 cm2 working areas respectively. These results were achieved with both optimized Josephson junction fabrication and a novel multilayer fabrication route. However, the proposed processes cannot ensure both high JJ parameters reproducibility and high wafer filling-factor. Previously, different methods have been reported for tuning JJ room temperature resistance \(\:{R}_{N}\)18,33,34. With a post fabrication laser-annealing of each superconducting qubits18,35,36 a variation coefficient \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) can be further improved down to 1% over a standard chip. However, it requires special equipment and is effective for single Josephson junctions only (highly integrated junctions or JJ arrays are difficult to treat in a control way due to non-local nature of laser annealing with a few microns impact radius).

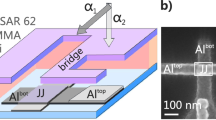

(a) General view of a 4-inch wafer with 96 JJ test matrix inside 70 × 70 mm2 (49 cm2) working area. Each test matrix combines 10 Josephson junction, bandage structure and Al contact pad. (b) A shadow evaporation process scheme. We used standard Dolan bridge technique with evaporation angles \(\:{a}_{1}\) = 40° and \(\:{a}_{2}\) = 0°. (c) JJ evaporation technological steps: (I) Al ground layer evaporation, (II) ground layer dry etching, (III) JJ e-beam litho, evaporation and lift-off, (IV) Al-bandage evaporation. (d) Scanning electron microscopy of Josephson junctions with 0.010 µm20.025 µm2 and 0.090 µm2 areas.

In this paper, we demonstrate a robust Al/AlOx/Al Dolan-bridge Josephson junction fabrication process on 4-inch wafers with preliminary shadow evaporation bias resist mask correction and comprehensive oxidation optimization. We propose a model for two-layer resist mask biasing at a wafer-scale, which allows compensating shadow evaporation JJ dimensions shrinks. It takes into account the changes in evaporation angle over a wafer, resist mask geometry, shadow evaporation process parameters including evaporation source geometry. We use a non-point evaporation source for the model that allows increasing the precision of bias calculation for the wafer of different diameters. According to the model each JJ electrode dimension is corrected for the calculated bias depending on its position (coordinates) on the wafer. We named this wafer topology preparation process Shadow Evaporation Bias Correction (SEBi correction). It results in Josephson junction area variation coefficient (\(\:{CV}_{A}\)) improvement down to 1.1% for the critical dimensions from 130 × 170 nm2 to 150 × 670 nm2 over 70 × 70 mm2 wafer working area. Next, we investigate JJ oxidation process (oxidation method, pressure and time) and its impact on room temperature resistance reproducibility. We combine both SEBi correction and oxidation best practices for 4-inch wafers improving \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) down to 6.0% for 0.025 µm2 JJ area and 4.0% for 0.090 µm2 JJ area for 70 × 70 mm2 (49 cm2) wafer working area (4.1% and 2.3% for 50 × 50 mm2 (25 cm2) working area correspondingly). In general, these results can be further improved with junction’s post fabrication treatment techniques35,36.

Experimental details

For this study, we used 4-inch high-resistivity silicon wafers (> 10000 Ω-cm). First, the substrate was cleaned in Piranha solution at 80 °C, followed by dipping in 2% hydrofluoric bath. Second, 120 nm Al film was deposited by the electron-beam evaporation method. Contact pads were defined using a laser direct-writing lithography and wet etch. Josephson junctions are evaporated using our optimized Dolan bridge technology39,40 with ultra-low Al electrodes edge roughness. The substrate is spin-coated with a resist bilayer (500 nm MMA-EL9 copolymer and 100 nm AR-P 6200 (CSAR) resist) and exposed with 50 keV electron-beam lithography [Fig. 1b]. The development is performed in a bath of Amyl acetate followed by rinsing in IPA for the top layer and IPA: DiW solution for the MMA copolymer. Descum process is carried out after development to clean the substrate from organic residues. Then the junction electrodes are shadow-evaporated in an ultra-high vacuum deposition system. First evaporated Al junction electrode is 25 nm thick and second is 45 nm. We investigate how the oxidation conditions of the tunnel barrier – the oxidation type, time and pressure – affect the JJ room temperature resistance \(\:{R}_{N}\). The deposition rate was chosen to provide a minimum for both the root mean square surface (RMS) roughness and the line edge roughness (LER) of the bottom electrode39. Then aluminum bandages are defined and evaporated using the same process as for the junctions with an in-situ Ar ion-milling to provide good electrical contact of the junction with the base layer. Lift-off is performed in a bath of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone with sonication at 80 °C and rinsed in a bath of IPA with ultrasonication [Fig. 1c].

Figure 1a shows the general view of the test topology. To characterize \(\:{R}_{N}\) variation over a wafer, we patterned 96 matrices with the junctions of three different areas as \(\:A\) = 0.010 µm2, \(\:A\) = 0.025 µm2and \(\:A\) = 0.090 µm2[Fig. 1d]. The surface quality and the junction dimensions were measured by scanning electron microscopy. In our study, we focused on room temperature characterization as a widely used method30,37,38,41 for assessing the reproducibility of Josephson junctions on wafers. Crucially, \(\:{R}_{N}\) variations are strongly correlated with cryogenic junction parameters (critical current \(\:{I}_{c}\) and qubit frequency \(\:f\)), as they directly reflect fabrication process variations in junction area and tunnel barrier properties42,43. The \(\:{R}_{N}\) dispersion values are calculated using an automatic measurement with a probe station. We optimized both voltage frequency and amplitude of probing signals from LCR Meter to increase our measurements precision which improve \(\:{R}_{N}\) standard deviation from 3.2 to 0.5%. A room temperature resistance variation coefficient (\(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\)) and Josephson junction area variation coefficient (\(\:{CV}_{A}\)) are described by:

.

where \(\:{\sigma\:}_{{R}_{N}}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{A}\) – standard deviation of the room temperature resistance \(\:{R}_{N}\) and Josephson junction area \(\:A\).

A transmon qubit resonance frequency vs. room temperature resistance of Josephson junction is described by38:

.

Experimental results and discussion

Shadow evaporation model

The limitations in Josephson junction parameters reproducibility are originated from both e-beam lithography and shadow evaporation processes37,41. The reason is a diverging metal flow forming during electron-beam evaporation. The conical shape of the metal flow leads to different evaporation angle along the wafer results in changing JJ critical dimensions21. Here, we proposed the shadow evaporation process model which eliminates JJ geometry position dependence. The model parameters are the thickness of the top (\(\:H\)) and bottom (\(\:h\)) layers of two-layer resist mask, substrate-holder tilt angle (\(\:{a}_{0}\)), JJ resist mask width (Wbot and Wtop), structure position on the wafer (\(\:X,\:Y)\:\)and the distance between crucible and substrate-holder (\(\:D\)) [Fig. 2a]. The actual evaporation angle taking into account the structure position on the wafer is described by:

.

The area of Josephson junction (\(\:{A}_{overlap}^{{\prime\:}}\left(X,Y\right)\)) at the position on the wafer with coordinates (X, Y) is described by:

.

where \(\:{W}_{top}^{{\prime\:}}\left(X,Y\right)\) and \(\:{\:W}_{bot}^{{\prime\:}}\left(X,Y\right)\) are the width of the top and bottom Al electrodes, respectively, evaporated at actual angle \(\:\left({\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\).

(a) The shadow evaporation model geometric representation. Josephson junction dimensions change depending on its wafer position. The proposed model takes into account the source distance \(\:D\), thickness of the top (\(\:\text{H}\)) and bottom (\(\:\text{h}\)) layers of organic mask, and shadow evaporation regime parameters \(\:{{\upalpha\:}}^{{\prime\:}}\). A non-point source model is used to increase the bias calculation precision. (b) Bias corrections of bottom Al electrode dimensions over the wafers. I Bias corrections zones excluding model parameters, II SEBi correction with a point evaporation source, III SEBi correction with a non-point evaporation source. (c) Experimentally measured distribution of Josephson junction areas over the wafers for 130 × 170 nm2 (0.025 µm2top map) and 130 × 670 nm2 (0.090 µm2bottom map) before (left) and after (right) SEBI correction with a non-point evaporation source.

Figure 2b (II) shows the required bias corrections of resist mask dimensions over 70 × 70 mm2 depending on the JJ position on the wafer in case of point-shape evaporation source. It includes both effects of shading of the evaporated Al electrode by the resist mask and changing in the evaporation angle on structure position on the wafer ((see in the supplementary materials Fig. S1-S3)). One can increase the accuracy of the model, if a more realistic round-shape evaporation source is used [Fig. 2b (III)]. In this case the Al electrode width depending on its position are described as:

.

Next issue is a bottom Al electrode evaporation process, when a thin Al film grows on a surface and sidewalls of resist mask. It leads to a decreased width of the resist mask at the next step of a top Al electrode evaporation. The grown Al film thickness depending on its position on a wafer is given by the relation:

.

where \(\:{T}_{0}\) – a calibrated film thickness at \(\:{a}_{0}\) = 0.

The resulting equation for top electrode dimensions is given by the relation:

.

We used the relations (5) and (7) to calculate final evaporated width of bottom and top Al electrodes over the wafer, respectively. Then we applied SEBi corrections of Josephson junction dimensions over a wafer using the proposed model. Figure 2c shows the experimental results of the SEBi corrections model verification. We demonstrate decreasing in JJ area variation coefficient (\(\:{CV}_{A}\)) from 7.5% down to 1.1% for 0.025 µm2 JJ area and from 6.0% down to 1.0% for 0.090 µm2 JJ area.

The wafer-scale JJ room temperature resistance-map depending on the optimization step for 0.025 µm2 and 0.090 µm2 junction areas: (a) the resistance variation coefficient (\(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\)) for JJ with static oxidation without electrodes dimensions corrections is 16% (130 × 170 nm2) and 14% (130 × 670 nm2) for 70 × 70 mm2 (49 cm2) working area; (b) using only SEBi correction reduces \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) down 8% (0.025 µm2 JJ area) and down to 6% (0.090 µm2 JJ area) for the same working area. (c) The proposed SEBi correction and high-pressure dynamic oxidation allows decreasing the room temperature resistance variation coefficient down 6% (0.025 µm2 JJ area) and down to 4% (0.090 µm2 JJ area) for 70 × 70 mm2 working area. For 50 × 50 mm2 working area (25 cm2orange square), it is improved down to 5.2% (0.025 µm2 JJ area) and 3.4% (0.090 µm2 JJ area). For the smallest 40 × 40 mm2 working area (16 cm2green square), it is improved down to 4.1% (0.025 µm2 JJ area) and 2.3% (0.090 µm2 JJ area).

Comprehensive oxidation optimization

Next, we measure JJ room temperature resistance reproducibility over a 4-inch wafer in order to verify our model. The resistance variation coefficient \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) for JJ with static oxidation without electrodes dimensions corrections are 16% (for 130 × 170 nm2 junctions) and 14% (for 130 × 670 nm2 junctions) for 70 × 70 mm2 working area [Fig. 3a]. There are two key reasons for wafer-scale JJ resistance nonuniformity, which are JJ area variation (larger \(\:{\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) provides wider evaporation shade of the top resist [Fig. 2a], resulting in position-dependent JJ area over a wafer) and tunnel barrier thickness variation (non-stable poly-Al grain size inside JJ and oxygen concentration across the wafer). Using SEBi correction, we almost eliminate the influence of JJ area variation, decreasing \(\:{CV}_{A}\) down to 1.1%. It results in decreasing \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) from 16% down to 8% (for 130 × 170 nm2) and from 14% down to 6% (for 130 × 670 nm2 junctions) using the same static oxidation process [Fig. 3b]. One can notice a pronounced gradient in JJ resistance from the left (bigger resistance) to the right (smaller resistance) edge of the wafer.

The tunnel barrier growth process can be divided into two oxidation stages: the first stage, a very fast almost linear vs. time oxide growth up to around 0.5–1.0 nm thickness and, the second stage, much slower (exponential like) thicker oxidation44. For static oxidation an oxygen transient time to reach the desired oxidation pressure, take a considerable part of the overall oxidation time (several minutes). During the oxygen intake, the wafer edge located closer to the oxygen inlet is oxidized faster (first stage) due to enhanced partial (local) pressure and constant refresh of pure oxygen. In this case, the main contribution to a tunnel barrier thickness gradient is the oxygen inlet position in the oxidation chamber. To solve this problem, one can dramatically lower the partial oxygen pressure during oxidation to reduce the influence of oxygen intake time and improve its concentration uniformity over a wafer. We uses dynamic oxidation with order of magnitude lower oxygen pressure, implementing uniform pure oxygen supply during whole oxidation process (Table 2). The oxygen has faster and more evenly, diffusion at the wafer surface in these conditions leading to high quality and homogeneous tunnel barrier growth36. Using SEBi correction with dynamic oxidation we demonstrate decreasing \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) from 8% down to 6% (for 130 × 170 nm2) and from 6% down to 4% (for 130 × 670 nm2) for 70 × 70 mm2 working area [Fig. 3c] (results for JJ 100 × 100 nm2 can be found in the supplementary materials Fig. S4 and Table S1). For the widely used 40 × 40 mm2 working area it is improved to 4.1% and 2.3%, respectively. The obtained resistance values correspond to the critical currents range from 10 to 100 nA widely used for high-coherent superconducting qubits fabrication. The proposed technique is also applicable for JJ fabrication with high critical currents (more than 0.5 µA), which can be used for Josephson parametric amplifiers and highly efficient superconducting quantum memory45.

Conclusion

Motivated by the challenging task of a high-uniformity Josephson junction fabrication for scalable quantum computing, we undertook a systematic study to identify the reasons and sources of room temperature resistance variation. In this paper, we demonstrate a robust Al/AlOx/Al Dolan-bridge Josephson junction fabrication process on 4-inch wafers with preliminary shadow evaporation bias resist mask correction and comprehensive oxidation optimization. We introduce a topology correction model for two-layer resist mask biasing at a wafer-scale, which takes into account a round-shaped evaporation source geometry. The proposed Shadow Evaporation Bias (SEBi) corrections allow us to increase the precision of bias calculation for the wafer-scale Josephson junction dimensions calculations. Using SEBi correction we almost eliminate the influence of JJ area variation, decreasing \(\:{CV}_{A}\) down to 1.1% for the critical dimensions from 130 × 170 nm2 to 130 × 670 nm2 over a 70 × 70 mm2 wafer working area. This step made it possible to separate the influence on JJ resistance variation from different fabrication processes (e-beam lithography, shadow evaporation and oxidation). Using only SEBi correction reduces \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) from 16% down to 8% (0.025 µm2 JJ area) and from 14% down to 6% (0.090 µm2 JJ area) for 70 × 70 mm2 working area. We combine both SEBi correction and high-pressure dynamic oxidation for 4-inch wafers improving \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) down to 6.0% for 0.025 µm2 JJ area and 4.0% for 0.090 µm2 JJ area for 70 × 70 mm2 (49 cm2) wafer working area. For 50 × 50 mm2 working area (25 cm2) it is improved down to 5.2% (0.025 µm2 JJ area) and 3.4% (0.090 µm2 JJ area). For the smallest 40 × 40 mm2 working area (16 cm2) it is improved down to 4.1% (0.025 µm2 JJ area) and 2.3% (0.090 µm2 JJ area). Based on the simulation results we show, that the best JJ reproducibility can be achieved with evaporation angle smaller than 45 degrees and thinner top layer organic mask. We assume, that the next steps in \(\:{CV}_{{R}_{N}}\) improving are JJ metal-substrate interface optimization and post-fabrication methods.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bruzewicz, C. D., Chiaverini, J., McConnell, R. & Sage, J. M. Trapped-ion quantum computing: progress and challenges. Appl. Phys. Rev. 6 (2), 021314 (2019).

Häffner, H., Roos, C. F. & Blatt, R. Quantum computing with trapped ions. Phys. Rep. 469, 155–203 (2008).

Buzaverov, K. A. et al. Low-loss silicon nitride photonic ICs for near-infrared wavelength bandwidth. Opt. Express. 31, 16227–16242 (2023).

Zwerver, A. M. J. et al. Qubits made by advanced semiconductor manufacturing. Nat. Electron. 5, 184–190 (2021).

Veldhorst, M. et al. An addressable quantum Dot qubit with fault-tolerant control-fidelity. Nat. Nanotech. 9, 981–985 (2014).

Childress, L. et al. Coherent dynamics of coupled electron and nuclear spin qubits in diamond. Science 314, 281–285 (2006).

Zhang, J., Hegde, S. S. & Suter, D. Efficient implementation of a quantum algorithm in a single Nitrogen-Vacancy center of diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 030501 (2020).

Smirnov, N. S. et al. Wiring surface loss of a superconducting Transmon qubit. Sci. Rep. 14, 7326 (2024).

Moskalenko, I. N. et al. High fidelity two-qubit gates on fluxoniums using a tunable coupler. Npj Quantum Inf. 8, 130 (2022).

Siddiqi, I. Engineering high-coherence superconducting qubits. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 875–891 (2021).

Zhiguang, Y. et al. Strongly correlated quantum walks with a 12-qubit superconducting processor. Science 364, 753–756 (2019).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

Chow, J., Dial, O. & Gambetta, J. IBM Quantum Breaks the 100-Qubit Processor Barrier. https://research.ibm.com/blog/127-qubit-quantum-processor-eagle (IBM Research, 2021).

Choi, C. Q. Ibm’s quantum leap: the company will take quantum tech past the 1,000-qubit mark in 2023. IEEE Spectr. 60, 46–47 (2023).

Pérez-Castillo, R., Serrano, M. A. & Piattini, M. Software modernization to embrace quantum technology. Adv. Eng. Softw. 151, 102933 (2021).

Di Carlo, Giuseppe Ruggero, et al. Investigating bursts of suppressed relaxation time using Quantum Inspire Starmon-5 and a 17-transmon processor. APS March Meeting Abstracts. 2024. (2024).

Dupont, M. et al. Quantum-enhanced greedy combinatorial optimization solver. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi0487 (2023).

Hertzberg, J. B. Laser-annealing Josephson junctions for yielding scaled-up superconducting quantum processors. Npj Quantum Inf. 7, 129 (2021).

Magesan, E. & Gambetta, J. M. Effective hamiltonian models of the cross-resonance gate. Phys. Rev. A. 101, 052308 (2020).

Chamberland, C. et al. Topological and subsystem codes on Low-Degree graphs with flag qubits. Phys. Rev. X. 10, 011022 (2020).

Roy, T. et al. Broadband parametric amplification with impedance engineering: beyond the gain-bandwidth product. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 262601 (2015).

Kaufman, R. et al. Josephson parametric amplifier with Chebyshev gain profile and high saturation. Phys. Rev. Appl. 20, 054058 (2023).

Ezenkova, D. et al. Broadband SNAIL parametric amplifier with microstrip impedance transformer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 232601 (2022).

White, T. C. et al. Traveling wave parametric amplifier with Josephson junctions using minimal resonator phase matching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 242601 (2015).

Ranadive, A. et al. Kerr reversal in Josephson meta-material and traveling wave parametric amplification. Nat. Commun. 13, 1737 (2022).

Peatáin, S. Ó. et al. Simulating the effects of fabrication tolerance on the performance of Josephson travelling wave parametric amplifiers. Supercond Sci. Technol. 36, 045017 (2023).

Qiu, J. Y. et al. Broadband squeezed microwaves and amplification with a Josephson travelling-wave parametric amplifier. Nat. Phys. 19, 706–713 (2023).

Bumble, B. et al. Submicrometer Nb/Al-AlOx/Nb integrated circuit fabrication process for quantum computing applications. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 19, 226–229 (2009).

Krantz, P. Investigation of transmon qubit designs-a study of plasma frequency Predictability (2010).

Muthusubramanian, N. et al. Wafer-scale uniformity of Dolan-bridge and bridgeless Manhattan-style Josephson junctions for superconducting quantum processors. Quantum Sci. Technol. 9, 025006 (2024).

Kreikebaum, J. M., O’Brien, K. P., Morvan, A. & Siddiqi, I. Improving wafer-scale Josephson junction resistance variation in superconducting quantum coherent circuits. Supercond Sci. Technol. 33, 06LT02 (2020).

Schmelz, M. et al. Wafer-Scale al junction technology for superconducting quantum circuits. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 34, 1701005 (2024).

Pappas, D. P. et al. Alternating-bias assisted annealing of amorphous oxide tunnel junctions. Commun. Mater. 5, 150 (2024).

Korshakov, N. D. et al. Aluminum Josephson junction microstructure and electrical properties modified by thermal annealing. Sci. Rep. 14, 26066 (2024).

Zhang, E. J. at al. High-performance superconducting quantum processors via laser annealing of transmon qubits. Sci. Adv. 8, eabi6690 (2022).

Kim, H. et al. Effects of Laser-Annealing on Fixed-Frequency superconducting qubits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 142601 (2022).

Takahashi, T. et al. Uniformity improvement of Josephson-junction resistance by considering sidewall deposition during shadow evaporation for large-scale integration of qubits. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 62, SC1002 (2023).

Lang, S. et al. Aluminum Josephson junction formation on 200 mm wafers using different oxidation techniques. ECS Trans. 111, 1 (2023).

Moskalev, D. O. et al. Optimization of shadow evaporation and oxidation for reproducible quantum Josephson junction circuits. Sci. Rep. 13, 4174 (2023).

Pishchimova, A. A. et al. Improving Josephson junction reproducibility for superconducting quantum circuits: junction area fluctuation. Sci. Rep. 13, 6772 (2023).

Bhatia, E. et al. Enabling 300 mm Wafer-Scale Fabrication of Superconducting Quantum Devices. In 2024 35th Annual SEMI Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference (ASMC) (IEEE, 2024), pp. 1–6.

Osman, A. et al. Mitigation of frequency collisions in superconducting quantum processors. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 043001 (2023).

Broom, R. F. Some temperature-dependent properties of Niobium tunnel junctions. J. Appl. Phys. 47, 5432–5439 (1976).

Jeurgens, L. P. H., Sloof, W. G., Tichelaar, F. D. & Mittemeijer, E. J. Growth kinetics and mechanisms of aluminum-oxide films formed by thermal oxidation of aluminum. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 1649–1656 (2002).

Matanin, A. R. et al. Toward highly efficient multimode superconducting quantum memory. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 034011 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Technology was developed and samples were fabricated at Quantum Park (BMSTU Nanofabrication Facility, Shukhov Labs, FMNS REC, ID 74300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A.M., N.D.K, D.O.M. and I.A.R. conceptualized the ideas of the project. D.A.M., N.D.K., A.A.S. and M.I.T. fabricated experimental samples and discussed results. D.A.M. and A.S.S. performed morphology characterization. N.D.K. performed shadow evaporation simulation. N.S.S., E.I.M and A.R.M. conducted the electrical characterization of the experimental samples. D.A.M., N.D.K, D.O.M. and I.A.R. analyzed the experimental data and discussed the results. D.A.M., N.D.K, D.O.M. and Y.V.P. prepared writing-original draft. I.A.R. reviewed and edited the manuscript. I.A.R. supervised the project. All authors analyzed the data and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moskaleva, D.A., Korshakov, N.D., Moskalev, D.O. et al. Wafer-scale uniformity improvement of Dolan-bridge Josephson junction by shadow evaporation bias correction. Sci Rep 15, 28097 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08787-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08787-5